Train undergraduate medical students to practice point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in the urgency and emergency module of the medical internship.

MethodsThe study was carried out through the Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma theoretical–practical ultrasonography course applied to students in the 11th semester of the CESUPA medical course.

ResultsIt was found that most university students demonstrated an improvement in their ability to carry out and grasp knowledge about the subject after applying theoretical and practical classes on an ultrasound device and ultrasound training simulator.

ConclusionThe improvement in student performance after the practical activity encourages discussion about the importance of curricular adjustment to adapt to technological advances in the medical field.

Capacitar a estudiantes de pregrado de medicina para la práctica de ultrasonido básico a pie de cama en el módulo de Urgencia y Emergencia del internado médico.

MétodosEl estudio se realizó a través del Curso de Ultrasonografía Teórico-Práctico E-FAST aplicado a estudiantes del undécimo semestre de la carrera de medicina del CESUPA.

ResultadosSe encontró que la mayoría de los estudiantes universitarios demostraron una mejora en su capacidad para realizar y captar conocimientos sobre el tema luego de aplicar clases teóricas y prácticas en un ecógrafo y simulador de entrenamiento en ultrasonido.

ConclusiónLa mejora en el rendimiento de los estudiantes luego de la actividad práctica propicia la discusión sobre la importancia del ajuste curricular para adaptarse a los avances tecnológicos en el campo médico.

The curriculum of the Undergraduate Medical Schools in recent decades has come to include complementary aspects of profile, skills, competencies, and content, with the health needs of individuals and populations identified by the health sector as the axis of curricular development, including ethical and humanistic dimensions. The Pedagogical Projects of the Medicine Courses began to include medical practices, simulated or not, from the initial levels, as well as immersion in health services and the reality of the health-disease process in communities.1,2

From the insertion of active teaching methodologies, the teaching–learning process began to be based on the assumption that the transmission of knowledge and skills, supported by technical–scientific advances, leads to an adequate level of professional practice. Practices not carried out in health centers simulate professional work through training in a different environment, which may involve real characters or realistic simulators, transforming the learning process and the applicability of medical skills.3,4,5

With global technological evolution, access to information and more developed health services has expanded, especially with regard to imaging exams. The evolution of radiology in the medical context has transformed and facilitated clinical practice, providing vast complementarity to care and allowing greater access to early diagnoses and treatments.6,7

Currently, the greater availability of devices, especially ultrasound, and their portable versions, has made high-difficulty procedures increasingly accessible in any environment, reducing duration and providing doctors with the possibility of improving the care provided. to your patient. The so-called point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), or ultrasound at the point of care, has become widely disseminated and a great ally for health professionals, bringing to light the need to implement its practice since medical graduation and to train the teachers.8,9

POCUS is currently part of the care protocols of all large health centers, with an important emphasis on the urgent and emergency context, notably in polytraumatized patients. This is because it provides 2 essential qualities in managing this audience: time and assertiveness.10,11

One of the protocols covered by POCUS is the Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (e-FAST or Extended FAST), which derives from the FAST technique, created in the 1980s, initially used in Germany and Japan, to evaluate through ultrasound blunt abdominal trauma and pericardial effusions at the emergency bedside in the initial 30 min of care, focusing on the active search for bleeding. In 1995, Lichtenstein described for the first time the use of 2 ultrasound lung windows, in the anterior midclavicular line between the third and fifth intercostal spaces in both hemithoraces, to evaluate what he called “lung sliding”, that is, the lung sliding that can be seen with each respiratory movement and that was absent in patients with pneumothorax.12,13

The inclusion of ultrasound in medical schools dates back to 1996, however, studies carried out in the United States have shown a rapid increase in the inclusion of ultrasound teaching in medical schools in the last decade and have brought to light the discussion about the revolutionary potential of the method in the teaching of basic sciences, which can be used in the context of anatomy, physiology, and understanding the physical examination. According to the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine database, in 2017, 18 medical schools already reported full integration of the curriculum with ultrasound practice. Still a small number, but with signs of exponential growth.14,15

Still in the United States, a study that compared the knowledge of doctors and residents about the FAST protocol before and after theoretical–practical peer-to-peer training and in a training model showed a significant increase in the ability to understand and apply the FAST technique. Examination between assessments.16

It is also possible to mention 2 systematic reviews already published. Mircea et al. described the findings of nearly 3 dozen publications, stating that “ultrasound should always be the choice as an ideal support tool in medical education”. Similarly, Lane et al. described the history of clinical ultrasound and ultrasound in medical education, citing 50 publications, and concluded that “ultrasound in medical education is entrenched and will grow exponentially in the coming years” and called for the allocation of more resources.14,17

Taking the above as a starting point, it is proposed to train the POCUS in the urgency and emergency module of the medical internship, innovating the curricular proposal based on the National Curricular Guidelines and aiming to expand the training of the FAST Protocol Extended, a technique widely used in emergency services where recent graduates will work after completing their degree.

Materials and methodsThe study was carried out with 42 students enrolled in the 11th period of the medical course through the theoretical assessment of POCUS at the Medical Internship, applied to research participants before and after theoretical–practical classes, as well as 3 practical assessment stations.

The study was developed on the premises of the Realistic Simulation Center of the Centro Universitário do Estado do Pará, in the city of Belém, State of Pará, Brazil.

The students were part of the project “I theoretical–practical ultrasonography course e-FAST”, held over 2 days, in the following stages.

On the first day, they underwent the “theoretical assessment of POCUS in the Medical Internship” test.

Subsequently, 4 h of theoretical classes were presented on the use of ultrasound methods at the point of care, with an emphasis on the practice of the e-FAST protocol.

The theoretical classes included the teaching of physical principles, the parameters of the ultrasound device and its handling, the e-FAST protocol technique, the technical terms that can be covered when carrying out the exam and the interpretation of its findings.

On the second day, divided into 2 groups of 20 and 22 students, respectively, the students participated in practical classes:

First peer-to-peer stage, with a regular ultrasound device to apply the exam technique, posture, and positioning, assessment of ultrasound anatomy and understanding of image formation.

The second stage was carried out using the SonoSim Starter Edition Ultrasound Training Simulator, to evaluate pathological findings, provided without conflict of interest for this research by the company Laerdal Brasil.

After completing the theoretical–practical process, the students were once again subjected to the test “theoretical assessment of POCUS at the Medical Internship”, for comparative purposes.

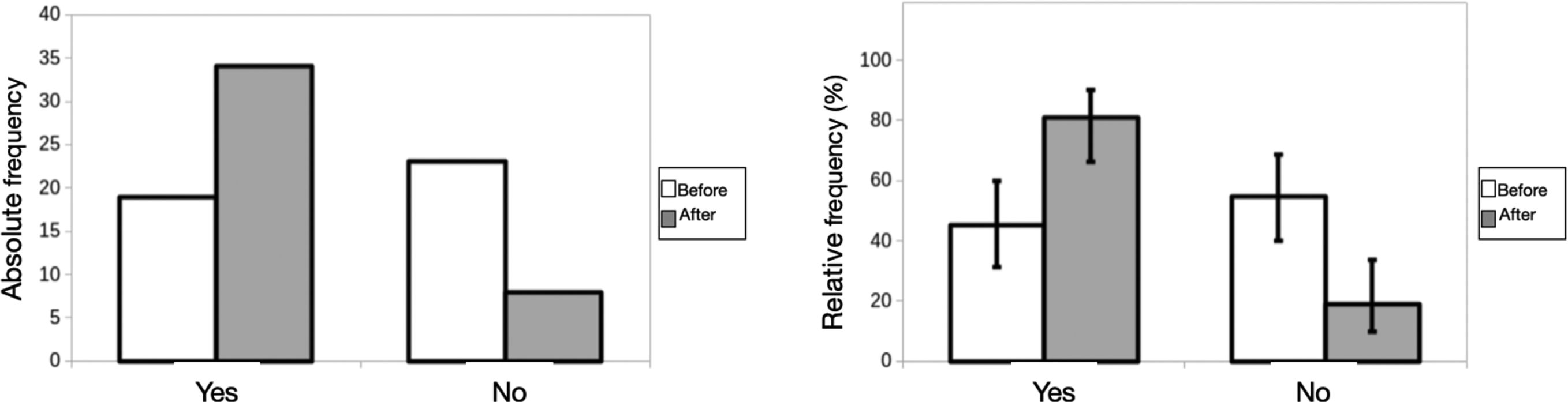

After 10 days of the e-FAST theoretical–practical ultrasonography course, the students were subjected to 3 practical evaluation stations, designed along the lines of the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE).

Results and discussionPOCUS has been widely disseminated throughout the medical world, covering the most diverse sectors and with multiple purposes. In the context of trauma, technological evolution has served to include imaging exams in initial care, especially in cases of multiple trauma patients. The complementary diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound shortened the time of care and hospital stay and increased the assertiveness of medical procedures, gaining strength in different scenarios. The POCUS practice has spread widely in Brazil in recent years and has been evolving significantly quickly, overcoming the barriers of private medicine and establishing itself in public services.

The inclusion of ultrasound methodology in medical schools has been advocated over the years by several medical education scholars, as Barloon et al. already demonstrated in 1998, by dividing students into groups of conventional practice and ultrasound practice and demonstrating greater accuracy in the results obtained for the second.18

Furthermore, Lane et al., in 2015 and Miller et al., in 2017, demonstrated that students' knowledge was superior after applying practical classes in ultrasound and led 95% of them to declare that this educational practice enhanced their medical education, expanding theoretical knowledge and skills, not only in the practice of imaging examinations but also in the general physical examination, since the anatomical domain also underwent significant reinforcement.14,15

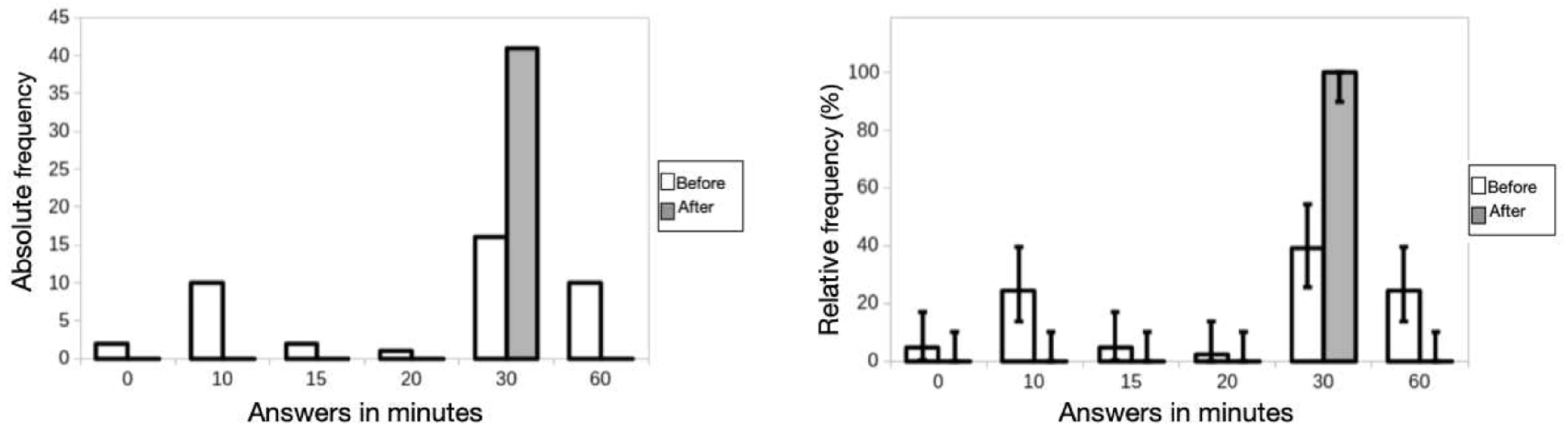

The current study carried out at the CESUPA Realistic Simulation Center—a space that has several simulated practice environments, allowing students a wide range of applied knowledge—resulted in the combined result of the theoretical and practical assessments of the present study, a greater apprehension of knowledge after applying peer-to-peer classes and in realistic simulators (Fig. 1), corroborating not only the aforementioned studies but also MAJ Monti and LTC Perreault, who in 2020 pointed out a significant increase in the ability to understand and apply the exam technique, defending the implementation of training practical training in ultrasound in the undergraduate medical curriculum.16

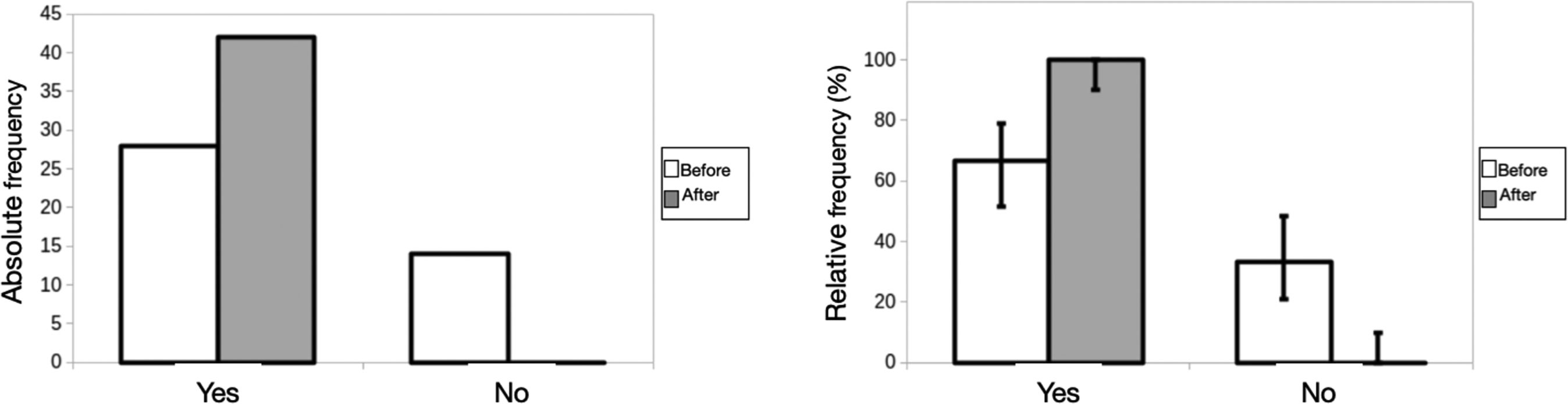

It is evident, in the current study, based on the analysis of the results obtained, that the lag in medical literature released in Brazil still guides students based on the FAST protocol, although it was changed in 2004, when it started to include windows lung diseases and assumed the nomenclature of Extended FAST or e-FAST. The questions that cover exclusive characteristics of the old protocol, such as the assessment of pericardial effusion, had significant successes in the pre-course approach, undergoing little modification after the activities. This differs from issues such as pneumothorax assessment, with a much less-significant result before applying the theoretical–practical course (Figs. 2 and 3).

Low exposure to updated literature seems to be just one of the factors that lead to less knowledge apprehension. The practice of POCUS has undergone rapid expansion in the last 25 years, but ultrasound is an ancient science, derived from the study of acoustics initiated by Pythagoras during the sixth-century BC. In the field of medical education, ultrasound began his career in Germany, in 1996, through teaching anatomy to first-year students.

A study carried out by Tshibwabwa et al. in Ontario, Canada, over 4 years, showed that first-year medical students were able to expand their knowledge of the anatomy of the urinary and cardiovascular systems after three 90-min sessions taught by a team made up of anatomists and radiologists. In 2010, Afonso et al. concludes that second-year students at Wayne State University, in Michigan, United States, improved their diagnostic capacity through ultrasound practice applied to physical examination.19,20

Such scientific evidence has become strong enough that medical schools have begun to incorporate ultrasound into their curricula. The first attempts to introduce ultrasound into medical courses took place at the Hanover Faculty of Medicine, with results published in 1996, focused on teaching basic anatomy. Until then, the technique had been used sporadically, generally associated with medical residency programs and echocardiography, the latter by cardiologists. After a long process, which included peer-to-peer and patient studies, the results were considered extremely relevant: More than half of the students agreed that the technology helped in the learning process, allowing ultrasound to be gradually inserted into the curriculum.21

Still in this scenario, in 2003, another study was conducted at the Faculty of Medicine of Vienna, associating anatomy classes with ultrasound visualization from the first to the sixth year of graduation with even more expressive results: 93% considered the course important for medical practice and 96% requested new experiences in the area.22

The first medical school to present an ultrasound curriculum completely integrated into the course was the University of South Carolina, in the United States, in 2006, based on a medical emergency training model and divided into clinical and pre-clinical applications. Pre-clinical use was associated with the teaching of anatomy, physiology, and pathology, while clinical practice was associated with the application of problem situations in various clinical scenarios. In both, students were introduced to theoretical and practical modalities, as well as OSCEs.

Since then, several medical schools have similarly incorporated the teaching of ultrasound. In a review of ultrasound integrated into the curriculum at the University of South Carolina, Hoppmann et al. demonstrated that more than 90% of students reported feeling that curricular integration increased their understanding of basic sciences in pre-clinical education.23

There is no clear evidence of better outcomes for patients as a result of the implementation of ultrasound in Medical Schools, due to the scarcity of studies focused on this analysis, but several reasons are suggested by proponents. In a recent paper, California educators suggested four main rationales: “(I) it can enhance traditional learning; (II) it can train future doctors to improve their diagnostic and procedural skills; (III) it can promote coordinated and efficient patient care; and (IV) may serve as a model for advanced, specialty-specific, or interdisciplinary ultrasound training in undergraduate medical education and continuing medical education.”24

Despite already being well established internationally, as reinforced by Cook et al., the ultrasound curriculum still barely permeates pedagogical projects at the national level, currently showing little or no integration. In most cases, ultrasound practice is still related to extra-curricular activities, not always provided by higher education institutions, or, to a lesser extent, in isolated activities during the medical internship.25

A more recent modality that has been disseminated as an alternative to ultrasound practice in a hospital environment is the training simulator, developed to eliminate the need for real patients or mannequins in the teaching stages, enabling the study of pathological findings that are independent of hospital sampling and allowing training in a realistic simulation environment, expanding knowledge (Fig. 4).

The current study reinforces the studies mentioned by emphasizing the increase in knowledge demonstrated by students in the questions proposed and in the stages presented of the “I theoretical–practical ultrasonography course e-FAST”, as well as in the feeling reported by them, encouraging discussion about the importance of curricular adjustment to adapt to technological advances in the medical field.

ConclusionThe improvement in students' performance after implementing the e-FAST theoretical–practical ultrasound course in short-term memory was significantly relevant after comparing the answers presented in the questionnaire “theoretical assessment of POCUS in the Medical Internship”. The results obtained in long-term memory also showed great potential for knowledge acquisition after practical activity and clinical correlation.

Such results encourage discussion about the importance of adjusting the curriculum of undergraduate medical courses to adapt to technological advances in diagnostic imaging in the medical field.

FundingNo funders are listed in this research. It was all self-funding.

Ethics statementThe research was carried out after approval by the Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitário do Estado do Pará, under register number 6,075,716, obtained on May 23, 2023. Its methodology included the direct participation of human beings (students of the medicine), where all those individuals who signed the Free and Informed Consent Form participated.