Nursing students are expected to demonstrate a broad array of competencies that enable them to provide exemplary care and improve patient outcomes. These competencies comprise system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning. Exploring the relationship between system thinking, self-leadership, and problem-solving is crucial for nursing students to deliver exceptional care and improve patient outcomes. This study examines the relationships between system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning in nursing students to inform evidence-based educational interventions.

Material and methodsThe research study is a non-experimental cross-sectional survey design with Structural Equation Modeling to test the a priori hypothesized study model. The study was conducted among nursing students at a university in Angeles City, Philippines. Statistical analyses, including descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), are employed to investigate relationships and causal pathways among system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning.

ResultsFindings revealed robust relationships between system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning in nursing students, with system thinking and self-leadership explaining 36.5% of clinical reasoning variance. These findings underscore the value of incorporating system thinking and self-leadership training into nursing education to enhance clinical reasoning.

ConclusionThis research provides compelling evidence of a statistically significant link between clinical reasoning, system thinking, and self-leadership, underscoring the critical role of clinical reasoning in integrating these competencies and enhancing the Clinical performance of nursing students.

Se espera que los estudiantes de enfermería demuestren una amplia gama de competencias que les permitan brindar una atención ejemplar y mejorar los resultados de los pacientes. Estas competencias comprenden el pensamiento de sistemas, el autoliderzazgo y el razonamiento clínico. Explorar la relación entre el pensamiento de sistemas, el autoliderzazgo y la resolución de problemas es crucial para que los estudiantes de enfermería brinden una atención excepcional y mejoren los resultados de los pacientes. Este estudio examina las relaciones entre el pensamiento de sistemas, el autoliderzazgo y el razonamiento clínico en estudiantes de enfermería para informar sobre intervenciones educativas basadas en evidencia.

Materiales y MétodosEl estudio de investigación tiene un diseño de encuesta transversal no experimental con Modelado de Ecuaciones Estructurales para poner a prueba el modelo de estudio hipotetizado a priori. El estudio se llevó a cabo entre estudiantes de enfermería de una universidad en la ciudad de Angeles, Filipinas. Se emplean análisis estadísticos, incluyendo estadísticas descriptivas, análisis de correlación y Modelado de Ecuaciones Estructurales (SEM), para investigar las relaciones y los caminos causales entre el pensamiento de sistemas, el autoliderzazgo y el razonamiento clínico.

ResultadosLos hallazgos revelaron relaciones robustas entre el pensamiento de sistemas, el autoliderzazgo y el razonamiento clínico en estudiantes de enfermería, donde el pensamiento de sistemas y el autoliderzazgo explicaron el 36.5% de la varianza del razonamiento clínico. Estos hallazgos subrayan el valor de incorporar el entrenamiento en pensamiento de sistemas y autoliderzazgo en la educación de enfermería para mejorar el razonamiento clínico.

ConclusiónEsta investigación proporciona evidencia convincente de un vínculo estadísticamente significativo entre el razonamiento clínico, el pensamiento de sistemas y el autoliderzazgo, subrayando el papel crítico del razonamiento clínico en la integración de estas competencias y la mejora del desempeño clínico de los estudiantes de enfermería.

Nursing students are responsible for embodying diverse proficiencies that empower them to deliver exceptional care and enhance patient well-being, spanning the pivotal dimensions of system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning. System thinking involves understanding the intricate interconnectedness and mutual influences within a broader framework, enabling us to provide comprehensive and effective healthcare.1 Self-leadership is equally critical, as it gives us the autonomy to steer our aspirations and endeavors toward goal attainment, nurturing resilience and adaptability in the pursuit of excellent patient care.2 Clinical reasoning is integral to nursing and involves astute patient observation, information synthesis, comprehensive problem comprehension, strategic intervention planning, outcome evaluation, and reflective learning.3 Mastering these essential competencies enables nursing students to become prospective leaders adept at navigating complexity, embracing change, and perpetually elevating their professional practice.

Building on the importance of these competencies, it is essential to recognize how they intersect with the broader context of healthcare delivery. As an integral part of complex healthcare systems, nursing operates within an environment where numerous interconnected elements impact patient care. Within this framework, system thinking becomes a necessary competency for nursing students.4 It entails the ability to perceive and comprehend the interrelationships within a system.5 By adopting this approach, nurses can recognize the interdependencies among various components within the healthcare system, identify the root causes of problems, and implement effective solutions that address the underlying system issues.4 Additionally, by acknowledging the complex interactions within a healthcare system, students can identify potential causes and consequences of problems and develop innovative and efficient solutions.6 In the face of a patient safety issue, a nursing student with system thinking skills can comprehensively analyze the entire care process, identifying underlying factors contributing to the problem, such as breakdowns in communication or inadequate staffing.7 This comprehensive understanding enables them to propose and implement solutions that target the root causes rather than merely treating the symptoms.

Self-leadership is an essential attribute of nursing students' personal and professional growth, involving the ability to take accountability for one's actions, thoughts, and emotions.8 In nursing education, self-leadership empowers students to assume responsibility for their learning, set goals, and actively engage in proactive problem-solving. By nurturing self-awareness, self-motivation, and self-regulation, nursing students can effectively navigate the challenges they encounter throughout their studies and clinical placements, shaping their future practice as confident and adaptable healthcare professionals.9 Nursing students actively seek opportunities to improve their problem-solving skills when they take charge of their learning. They employ reflective techniques, such as debriefing sessions or journaling, to analyze their experiences and identify areas for growth.10 Moreover, self-leadership empowers nursing students with the resilience to navigate challenging situations, adapt to evolving circumstances, and uphold a positive mindset when engaging in clinical judgment tasks.11

While self-leadership plays a vital role in personal and professional development, the cultivation of clinical reasoning skills is equally essential for effective nursing practice. Developing competent clinical reasoning is crucial for nursing students, enabling them to navigate complex clinical scenarios, think critically, and make informed decisions.12,13 Effective clinical reasoning serves as a foundation for nurses' decision-making processes, allowing them to tackle broader healthcare challenges.14 However, many nursing graduates face challenges due to insufficient preparedness in this area. Therefore, nurse educators must prioritize instructional strategies that enhance clinical reasoning skills and address any deficiencies that could lead to poor decision-making and inadequate patient care.15 By cultivating strong clinical reasoning abilities, nursing students can contribute to positive patient outcomes, mitigate risks, and insure safe care delivery.

Developing proficient nursing professionals requires a deep understanding of the interplay between system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning. However, research has identified a significant gap in understanding how these variables intersect and impact one another. This study uses structural equation modeling to bridge this gap by exploring the relationships between system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning among nursing students. By examining these connections, we seek to clarify how these concepts relate, identify predictors of clinical reasoning, and inform evidence-based educational interventions that enhance nursing students' competencies, ultimately enabling them to deliver exceptional patient care.

Material and methodsThe research study employs a non-experimental cross-sectional survey design with Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to comprehensively evaluate the relationships and causal pathways among system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning. The study includes a purposive sampling of third- and fourth-year nursing students at a university in Angeles City, Philippines. This approach allows researchers to selectively target students who are most likely to have developed these competencies.

Respondents were third- and fourth-year nursing students enrolled in a nursing program at the time of the survey. Respondents were selected based on their current enrollment status and year of study, ensuring a sample with relevant experience and understanding of system thinking, self-leadership, and problem-solving concepts. Conversely, the exclusion criteria eliminated nursing students not enrolled in a program at the time, those who did not complete the questionnaire, and those who failed to provide informed consent. Additionally, irregular students without relevant learning experience (RLE) or clinical placements during the study period were excluded, as their lack of practical exposure could affect the study's outcomes.

A priori sample size calculation16 indicated that 161 participants were needed to achieve sufficient statistical power (0.80) for detecting a small to moderate effect (f2 = 0.03) at α = 0.05, given six latent and nine observed variables. Ultimately, 207 respondents qualified to participate and willingly completed the research questionnaire, reflecting a good sample effect size for examining the proposed model. Data collection for the study took place from May to July 2024. Prior to recruiting participants, ethical approval was secured from the University Ethics Review Board, ensuring that the research adhered to ethical standards and guidelines.

To control for potential biases, the study implemented several strategies, including selection of respondents within the defined sampling criteria and ensuring anonymity in responses to reduce social desirability bias. Additionally, participants were informed about the study's purpose and assured that their responses would remain confidential, which encouraged honest and accurate reporting. Regular instruction for data collectors was provided to insure consistency in administering the survey and addressing any participant questions, further minimizing biases in data collection.

InstrumentationThe self-administered study survey comprised three standardized, valid, and reliable Likert-scale instruments to assess various constructs, including the demographic data. The survey began with a socio-demographic section, where respondents provided information on their age, gender, civil status, and years of nursing experience. The System Thinking Scale (STS), a 20-item instrument developed by Dolansky et al. (2020), measured system thinking by evaluating system interdependencies in activities, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.89, indicating strong internal consistency. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale, from “Never” (0) to “Most of the Time” (4), with higher scores indicating greater proficiency in system thinking.17 The Abbreviated Self-Leadership Questionnaire (ASLQ), developed by Houghton, Dawley, and DiLiello in 2012, assessed self-leadership through nine items rated from 1 (Not at all Accurate) to 5 (Completely Accurate), covering Behavior Awareness, Volition, Task Motivation, and Constructive Cognition, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.73. Higher scores in each sub-construct denoted greater self-leadership proficiency.18 Lastly, the Clinical Reasoning Competency Scale (CRCS), developed by Bae et al. (2023), evaluated clinical reasoning competency with 22 items across plan setting, intervention strategy regulation, and self-instruction, using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92, indicating high reliability and validity. Higher scores reflected higher clinical reasoning competency.3

Data analysisAll data were analyzed using R Studio version 4.2.1. Descriptive statistics, including frequency distribution, percentage distribution, mean, and standard deviation, were utilized to summarize the demographic characteristics of participants as well as their system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning abilities. Descriptive statistics separately detailed these self-leadership components, including aspects such as Behavior Awareness and Volition, Task Motivation, and Constructive Cognition, and clinical reasoning, encompassing Intervention Strategy Regulation, Plan Setting, and Self-Instruction. Pearson's correlation analysis was then applied to examine the relationships, pairwise, between system thinking and various facets of self-leadership and between the components of clinical reasoning and both system thinking and self-leadership. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to comprehensively examine the interrelationships and causal pathways between system thinking, self-leadership, and clinical reasoning.

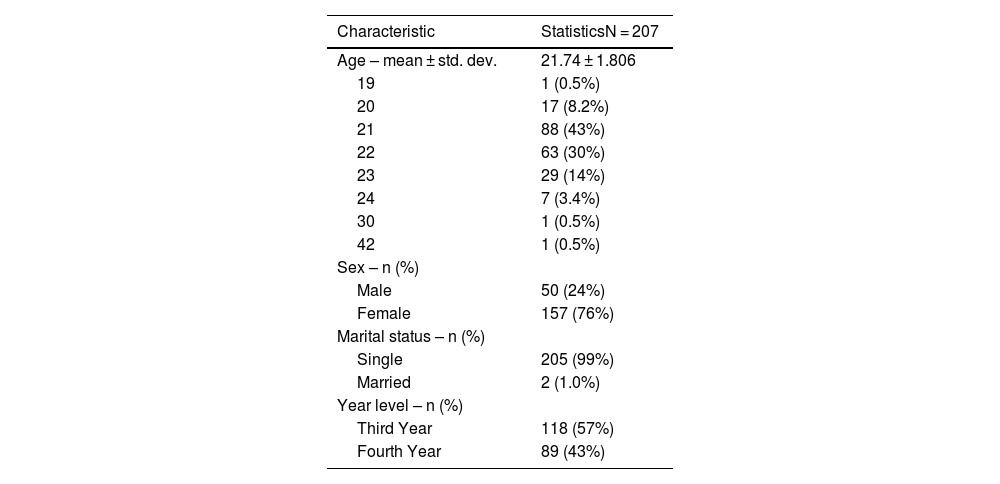

ResultsData analysis included 207 respondents, as presented in Table 1. The average age of the respondents is 21.74 years, with a standard deviation of 1.806 years. The majority of respondents are aged 21 (43%), followed by 22 years old (30%), with smaller percentages in other age groups, including one respondent each at ages 19, 30, and 42 (0.5% each). The sample is predominantly female, comprising 76% (157) of the respondents, while males represent 24% (50). Regarding marital status, nearly all respondents are single (99%), with only 1% (2 respondents) being married. In terms of academic standing, 57% (118) of the respondents are in Third-year, while the remaining 43% (89) are in Fourth-year.

Descriptive characteristics of the respondents.

| Characteristic | StatisticsN = 207 |

|---|---|

| Age – mean ± std. dev. | 21.74 ± 1.806 |

| 19 | 1 (0.5%) |

| 20 | 17 (8.2%) |

| 21 | 88 (43%) |

| 22 | 63 (30%) |

| 23 | 29 (14%) |

| 24 | 7 (3.4%) |

| 30 | 1 (0.5%) |

| 42 | 1 (0.5%) |

| Sex – n (%) | |

| Male | 50 (24%) |

| Female | 157 (76%) |

| Marital status – n (%) | |

| Single | 205 (99%) |

| Married | 2 (1.0%) |

| Year level – n (%) | |

| Third Year | 118 (57%) |

| Fourth Year | 89 (43%) |

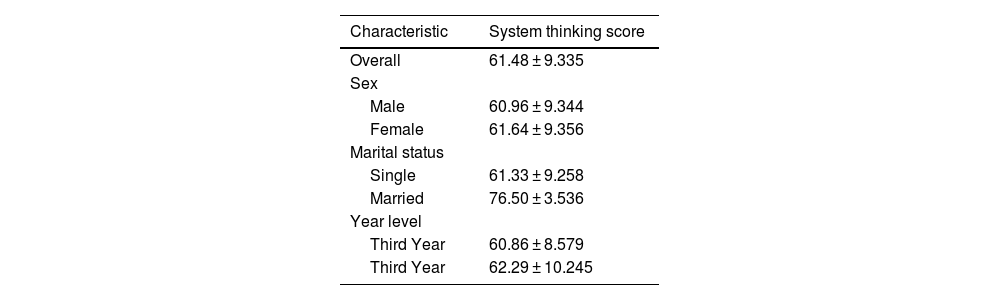

The summary of system thinking scores based on the STS Questionnaire shows that the overall average score among respondents is 61.48, with a standard deviation of 9.335 [Table 2], indicating a solid foundation in system thinking. When broken down by sex, males have an average score of 60.96 (SD = 9.344), while females score slightly higher with an average of 61.64 (SD = 9.356). This suggests that female respondents may have a marginally better grasp of system thinking concepts. Regarding marital status, single respondents have an average score of 61.33 (SD = 9.258), whereas married respondents have a notably higher average score of 76.50 (SD = 3.536). Lastly, by year level, Third-year students have an average score of 60.86 (SD = 8.579), while Fourth-year students score higher with an average of 62.29 (SD = 10.245). This trend suggests that as students progress through their nursing program, they develop stronger system thinking skills, likely due to increased exposure and experience in their clinical training.

Summary of the system scores of the respondents across characteristics using the System thinking score Questionnaire.

| Characteristic | System thinking score |

|---|---|

| Overall | 61.48 ± 9.335 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 60.96 ± 9.344 |

| Female | 61.64 ± 9.356 |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 61.33 ± 9.258 |

| Married | 76.50 ± 3.536 |

| Year level | |

| Third Year | 60.86 ± 8.579 |

| Third Year | 62.29 ± 10.245 |

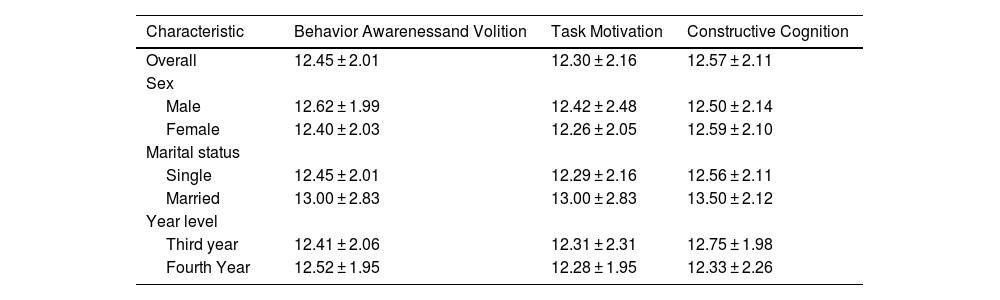

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of self-leadership scores across three key dimensions: Behavior Awareness and Volition, Task Motivation, and Constructive Cognition. The average scores among respondents are notably consistent, ranging from 12.30 to 12.57. A closer examination reveals that males slightly outperform females in both the Behavior Awareness and Volition (average score for males: 12.45) and Task Motivation (average score for males: 12.50) dimensions. Conversely, females show a slight advantage in Constructive Cognition, with an average score of 12.55 compared to 12.30 for males. Interestingly, while the sample of married respondents is small, they consistently score higher than single respondents across all dimensions, suggesting that marital status may play a role in self-leadership levels. For example, married individuals average 12.80 in Behavior Awareness and Volition, compared to 12.40 for their single counterparts. Analysis by year level further highlights the nuances in self-leadership scores. Third-year students excel in Constructive Cognition, averaging 12.60, while Fourth-year students achieve higher scores in Behavior Awareness and Volition, with an average of 12.70. Overall, these findings suggest a relatively uniform level of self-leadership among respondents, with subtle demographic variations indicating areas for further exploration and potential intervention.

Summary of the self-leadership scores of the respondents across characteristics using the Abbreviated Self-Leadership Questionnaire.

| Characteristic | Behavior Awarenessand Volition | Task Motivation | Constructive Cognition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 12.45 ± 2.01 | 12.30 ± 2.16 | 12.57 ± 2.11 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 12.62 ± 1.99 | 12.42 ± 2.48 | 12.50 ± 2.14 |

| Female | 12.40 ± 2.03 | 12.26 ± 2.05 | 12.59 ± 2.10 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 12.45 ± 2.01 | 12.29 ± 2.16 | 12.56 ± 2.11 |

| Married | 13.00 ± 2.83 | 13.00 ± 2.83 | 13.50 ± 2.12 |

| Year level | |||

| Third year | 12.41 ± 2.06 | 12.31 ± 2.31 | 12.75 ± 1.98 |

| Fourth Year | 12.52 ± 1.95 | 12.28 ± 1.95 | 12.33 ± 2.26 |

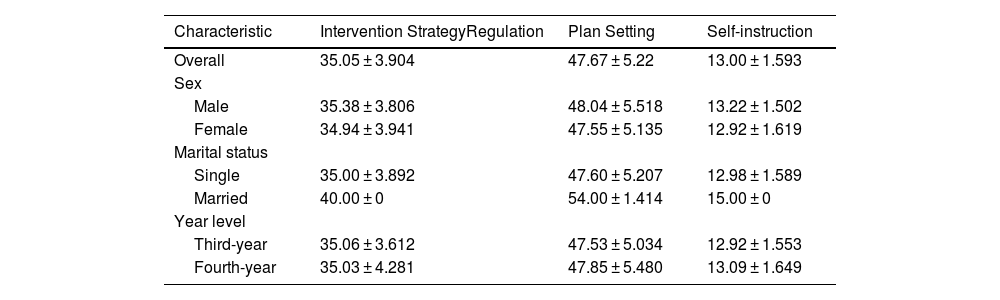

Table 4 presents the scores from the Clinical Reasoning Competency Scale, revealing consistent performance across the three dimensions: Intervention Strategy Regulation (average score: 35.05), Plan Setting (average score: 47.67), and Self-instruction (average score: 13.00). Notably, male respondents outperformed females across all dimensions, highlighting a slight gender disparity in clinical reasoning competencies. Interestingly, married respondents achieved significantly higher scores, approaching perfection in some areas. However, this result should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size of married participants. When analyzing the scores by year level, Third-year and Fourth-year students exhibited minimal differences, indicating that both groups possess similar clinical reasoning abilities. Overall, these findings suggest a generally consistent level of clinical reasoning competency among the respondents, with subtle variations observed based on sex and marital status. This consistency underscores the importance of fostering these skills across demographics to insure effective nursing practice.

Summary of the clinical reasoning scores of the respondents across characteristics using the Clinical Reasoning Competency Scale.

| Characteristic | Intervention StrategyRegulation | Plan Setting | Self-instruction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 35.05 ± 3.904 | 47.67 ± 5.22 | 13.00 ± 1.593 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 35.38 ± 3.806 | 48.04 ± 5.518 | 13.22 ± 1.502 |

| Female | 34.94 ± 3.941 | 47.55 ± 5.135 | 12.92 ± 1.619 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 35.00 ± 3.892 | 47.60 ± 5.207 | 12.98 ± 1.589 |

| Married | 40.00 ± 0 | 54.00 ± 1.414 | 15.00 ± 0 |

| Year level | |||

| Third-year | 35.06 ± 3.612 | 47.53 ± 5.034 | 12.92 ± 1.553 |

| Fourth-year | 35.03 ± 4.281 | 47.85 ± 5.480 | 13.09 ± 1.649 |

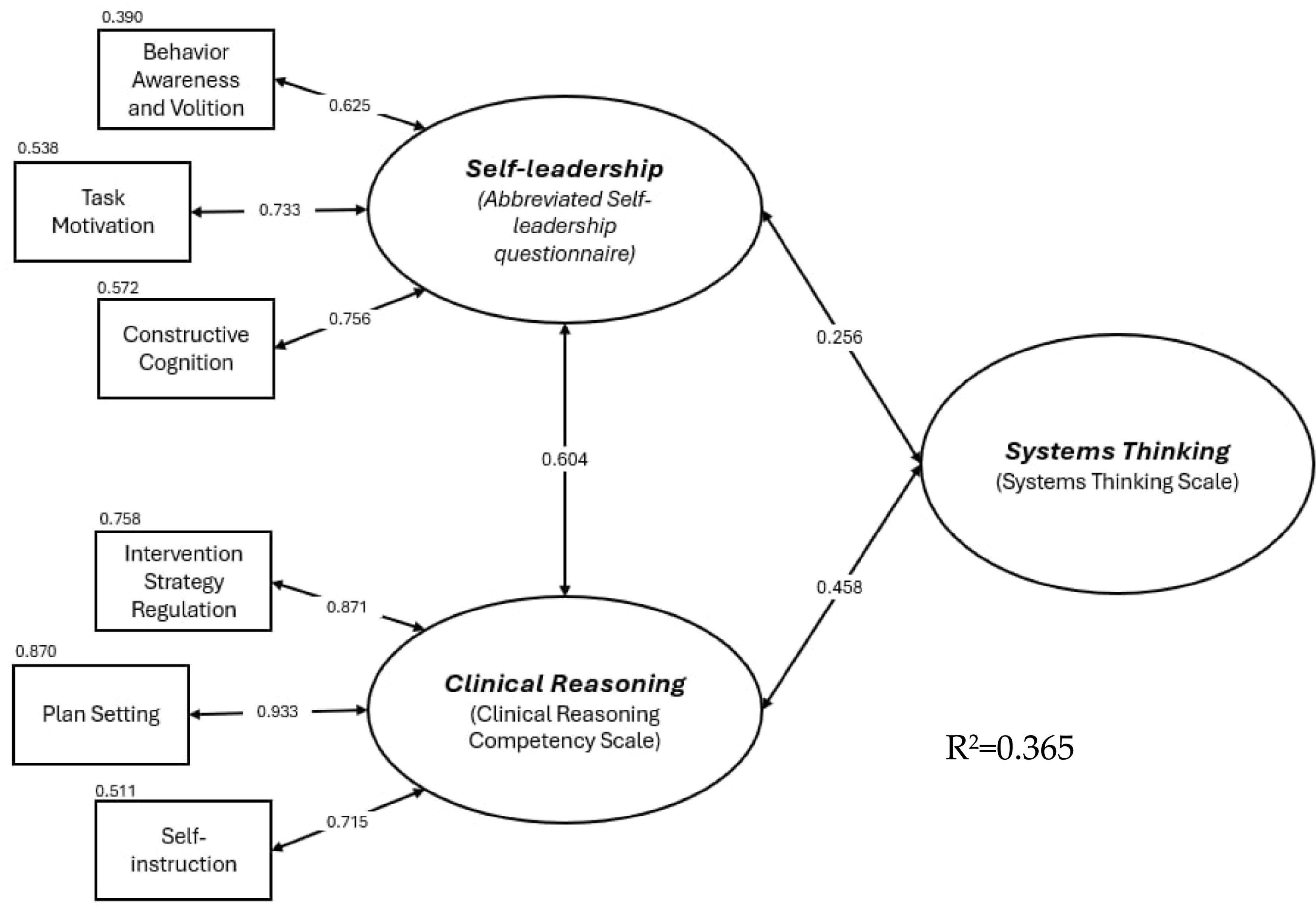

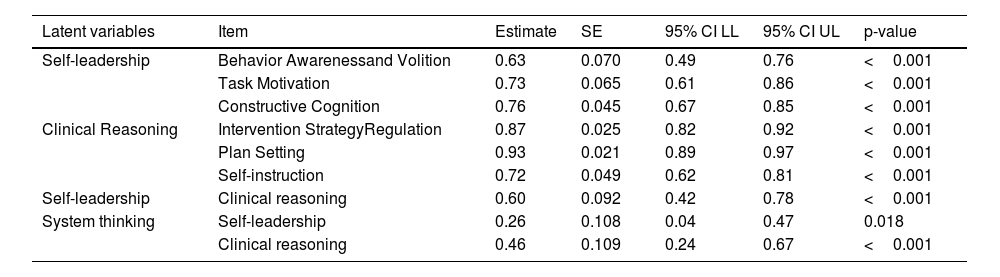

The Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) results in Table 5 demonstrate strong relationships between latent variables and their corresponding items, with good model fit indices (RMSEA = 0.077, p-value = 0.104, CFI = 0.969, SRMR = 0.039). Self-leadership, Clinical Reasoning, and System Thinking are all strongly interconnected. Self-leadership consists of three dimensions: Behavior Awareness and Volition, Task Motivation, and Constructive Cognition, all with significant and high loadings (0.63–0.76). Clinical Reasoning also shows strong loadings across its indicators (0.72–0.93). Notably, Self-leadership positively influences System Thinking (0.26), and Clinical Reasoning has a stronger influence on both System Thinking (0.46) and Self-leadership (0.60). These findings suggest that higher levels of Self-leadership and Clinical Reasoning contribute to better System Thinking and improved overall performance. By integrating the data, it becomes evident that fostering these competencies is crucial for developing effective nursing practices.

Structural equation modeling.

| Latent variables | Item | Estimate | SE | 95% CI LL | 95% CI UL | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-leadership | Behavior Awarenessand Volition | 0.63 | 0.070 | 0.49 | 0.76 | <0.001 |

| Task Motivation | 0.73 | 0.065 | 0.61 | 0.86 | <0.001 | |

| Constructive Cognition | 0.76 | 0.045 | 0.67 | 0.85 | <0.001 | |

| Clinical Reasoning | Intervention StrategyRegulation | 0.87 | 0.025 | 0.82 | 0.92 | <0.001 |

| Plan Setting | 0.93 | 0.021 | 0.89 | 0.97 | <0.001 | |

| Self-instruction | 0.72 | 0.049 | 0.62 | 0.81 | <0.001 | |

| Self-leadership | Clinical reasoning | 0.60 | 0.092 | 0.42 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| System thinking | Self-leadership | 0.26 | 0.108 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.018 |

| Clinical reasoning | 0.46 | 0.109 | 0.24 | 0.67 | <0.001 |

RMSE = 0.077, p-value = 0.104, CFI = 0.969, srmr = 0.039.

Fig. 1 illustrates our structural equation model. What transpired more from this result is that we obtained an R2 value of 0.365, indicating that system thinking and self-leadership collectively explain 36.5% of the variance in clinical reasoning. This proportion of variance explained is considerably moderate, suggesting that there may be factors beyond those included in the model that can contribute significantly to Clinical Reasoning.

DiscussionThe structural equation modeling (SEM) results confirm a strong fit between the theoretical framework and data, shedding light on the relationships between self-leadership, clinical reasoning, and system thinking. Key indices validate the model's strength: an RMSEA value of 0.077 and SRMR value of 0.039 indicate a good fit, while a CFI of 0.969 demonstrates an excellent fit. Additionally, a non-significant p-value (0.104) reinforces the model's validity. Collectively, these findings support the framework's relevance in understanding the dynamics between these constructs, providing valuable insights into their interconnected relationships.

Confirming a significant positive relationship between system thinking and self-leadership indicates that individuals who can adopt a holistic view of problems are likely to lead themselves more effectively. This finding underscores the potential value of incorporating system thinking training into nursing education to enhance self-leadership skills. For instance, nursing students who participate in simulations emphasizing goal-setting and critical thinking—key components of system thinking—demonstrate marked improvements in their self-leadership abilities.19 Additionally, the problem-solving skills cultivated through simulation practices are closely tied to self-leadership, suggesting that experiential learning environments can be crucial in developing these competencies. However, it is essential to recognize that this study does not account for external factors such as clinical exposure or mentorship that might further enhance these skills. It is critical to explore how these variables interact with system thinking and self-leadership development. By fostering system thinking in nursing curricula, educators can better prepare students to navigate complex clinical scenarios and take initiative in their professional development. Furthermore, nurses, including nursing students, who implement system thinking in patient care enhance their leadership abilities. The elements of system thinking and the necessary steps for its practical application highlight essential leadership qualities, including effective communication, collaborative teamwork, strategic problem-solving through recognizing patterns and relationships, self-reflection, and cultivating a shared vision.2

A significant positive relationship between system thinking and clinical reasoning suggests that students who are better at system thinking may also excel in clinical reasoning. This association further explains that system thinking in clinical reasoning helps handle uncertainty by allowing holistic viewing of patients' problems and facilitating understanding of complex interactions.20 Hence, clinical reasoning in nursing students is a complex thinking process that underlies clinical judgment, decision-making, and professional competence.21 However, the moderate fit implies that other variables could play a role in this relationship. Future research could investigate what additional factors—such as clinical exposure, mentorship, or simulation experiences—might strengthen this connection. Understanding these dynamics could help educators design effective training programs that integrate system thinking into clinical reasoning exercises.

Furthermore, the study's findings indicate that self-leadership exhibits a strong positive influence on clinical reasoning among nursing students. Specifically, self-leadership, encompassing behavior awareness, task motivation, and constructive cognition, significantly predicts clinical reasoning abilities. This aligns with previous research suggesting that self-leadership furthers critical thinking and problem-solving skills essential for effective clinical decision-making.22 The strong relationship between self-leadership and clinical reasoning underscores the importance of integrating self-leadership development into nursing education curricula.23 Although self-leadership demonstrated a notable influence on clinical reasoning, the structural equation model revealed a moderate relationship between the two constructs (Fig. 1). This suggests that while self-leadership is a significant factor of clinical reasoning, other factors also contribute to its development, necessitating further exploration.

Lastly, the structural equation model yields a moderate R2 value of 0.365, indicating that system thinking and self-leadership collectively explain 36.5% of the variance in clinical reasoning. This finding suggests that additional factors not captured in our model such as emotional intelligence, peer influence, educational methodologies, and practical experience, may significantly contribute to clinical reasoning. Emotional intelligence, for instance, can enhance interpersonal skills and decision-making, which are crucial in clinical settings. Peer influence may shape attitudes and behaviors among nursing students, fostering an environment that supports the development of clinical reasoning skills. Furthermore, varying educational methodologies—such as problem-based learning or experiential learning—could have different impacts on students' abilities to reason clinically. Further investigation into these unaccounted factors is warranted, underscoring the complexity of clinical reasoning and the need for a multifaceted approach in nursing education and practice. Future research should explore longitudinal effects, mediating variables, and comparative studies. By adopting a holistic approach, nursing educators can foster cognitive, emotional, and social growth, ultimately improving patient care and outcomes and shaping the next generation of nursing professionals.

Funding sourceNothing to Disclose.

Ethics committee approvalAngeles University Foundation-Ethics Review Committee 2023-CON-Faculty-005.