Doctor-patient communication, patient-centered care, and empathy are all crucial in health care. These topics should be addressed throughout the undergraduate medical curriculum, but this is not always feasible due to the significant resources required. Micro-level interventions are more feasible; however, the effects on students and the means of achieving them are unknown. Therefore, this study focuses on a micro-level, theory-based communication training intervention to help medical students understand the importance of patient-centered care and empathy.

MethodsWe conducted a design-based research study. We implemented a three-hour, role-playing-based communication seminar for forty-six fifth-year medical students at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, applying cognitive apprenticeship principles. The following qualitative data were collected: students' written reflections, interviews with students and teachers, and seminar observations.

ResultsThe written reflections indicated that students believe patient-centered care and empathy are not merely skills and attitudes to possess but values inherent to the medical profession. The interviews show that involvement in role plays, teacher guidance, and a positive learning atmosphere were essential to the intervention.

ConclusionThe intervention helped improve students' awareness and their attitude, allowed them to practice skills related to patient-centered care and empathy, and see them as values of the profession.

La comunicación médico-paciente, la atención centrada en él y la empatía son fundamentales. Estos temas deben abordarse a lo largo del currículum, pero requieren importantes recursos. Las intervenciones a pequeña escala son más factibles, pero se desconocen los efectos que tendrían en los estudiantes y cómo lograrlos. Este estudio se centra en una microintervención educativa en comunicación, basada en la teoría del aprendizaje, para ayudar a los estudiantes de medicina a comprender la importancia de la atención centrada en el paciente y la empatía.

MétodosEs un estudio de investigación basado en el diseño. Diseñamos e implementamos un seminario de tres horas basado en role-playing, para cuarenta y seis estudiantes de quinto año de medicina de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, aplicando principios de la teoría del aprendizaje cognitivo. Se recopilaron los siguientes datos cualitativos: reflexiones escritas de los estudiantes, entrevistas con los participantes.

ResultadosLas reflexiones escritas indicaron que la atención centrada en el paciente y la empatía no se consideran meras habilidades y actitudes a poseer, sino valores inherentes a la profesión médica. Las entrevistas muestran que la participación activa en los role-plays, el clima docente alcanzado y el soporte adecuado de los profesores fueron fundamentales para ello.

ConclusiónLa intervención contribuyó a mejorar la concienciación de los estudiantes y su actitud, les permitió practicar habilidades relacionadas con la atención centrada en el paciente y la empatía, y verlas como valores de la profesión.

Doctor-patient communication (DPC) is crucial for the proper care of patients. It establishes a therapeutic relationship based on trust with patients and their families.1 It should be systematically addressed in curricula, but this is not the case everywhere, as it requires considerable resources.2 Micro-level educational interventions are easier to implement, but we do not know how effective they are. This work explores how a micro-level intervention can help medical students reflect on the importance of patient-centered care (PCC) and empathy.

PCC is “the care that is respectful of and responsive to patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensures the patient values guide all clinical decisions”.3 In PCC, DPC is critical as it enables patients to provide input and actively participate in all choices about their health.4 A key concept in DPC and PCC is empathy. It supports the development of therapeutic relationships between carers and care recipients.5 Empathy in the context of health is defined as: “a predominantly cognitive (rather than an affective or emotional) attribute that involves understanding (rather than feeling) of the patient's experiences, concerns, and perspectives, combined with a capacity to communicate this understanding, and an intention to help”.6

In the Hispano-American context, there is consensus on a core communication curriculum for medical schools.7 Spanish legislation regulates it.8 However, DPC is only marginally addressed in the curriculum. It is mainly taught through lectures in preclinical years and assessed by written exams, and students ask for more practice, more feedback, and fewer lectures.9 The existence of training with simulated patients is known, but not used in teaching practice.10 Role-play is less expensive than other simulation methods and is more feasible.11 It promotes active learning.12 In supervised groups, reflection and insight in the patient and doctor roles are promoted, and empathic abilities are facilitated, not only for the practicing students but also for peers observing the group sessions.13

In our context, integrating DPC into the curriculum is not possible in the short term because of insufficient resources2: human, spatial, temporal, and financial.

A micro-level intervention seems more feasible, although it is unclear how it could best be designed and what the impact on students would be.

In cognitive apprenticeship learning theory (CA), the cognitive and meta-cognitive processes experts use when performing a task are the basis of teaching activities.14 It takes traditional apprenticeship thinking to a higher level because it teaches and makes explicit the often tacit processes involved in experts' handling of complex cognitive tasks. Furthermore, it stresses students' early and active engagement in the real-world professional context.15

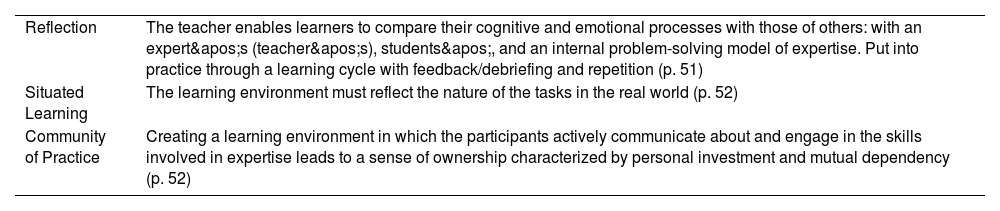

We chose CA because it allows medical students to transform theoretical knowledge into cognitive, attitudinal, and psychomotor skills essential for patient care.16Table 1 shows the three principles we used:

CA principles applied in intervention design.14

| Reflection | The teacher enables learners to compare their cognitive and emotional processes with those of others: with an expert's (teacher's), students', and an internal problem-solving model of expertise. Put into practice through a learning cycle with feedback/debriefing and repetition (p. 51) |

| Situated Learning | The learning environment must reflect the nature of the tasks in the real world (p. 52) |

| Community of Practice | Creating a learning environment in which the participants actively communicate about and engage in the skills involved in expertise leads to a sense of ownership characterized by personal investment and mutual dependency (p. 52) |

In this article, we present the results of how a micro-level CA-based communication training intervention helps medical students understand the importance of PCC and empathy.

MethodsStudy designWe conducted a design-based research study in an authentic educational environment, using mixed methods, and relying on the collaboration between designers, researchers, and practitioners.17 Only qualitative results are presented in this article.

InterventionCA principles were applied as follows: Role-playing allows students to observe and practice DPC, paying attention to the credibility of the scenarios (situated learning). Using formal observation tools helps students to analyze the scenes critically while observing role-plays (reflection). Additionally, an individual written reflection encourages students to deepen their understanding of what and how they have learned and how it applies to their clinical practice (reflection). Role-play participation, feedback, and debriefing will give students a central role by encouraging them to participate in discussions with peers and teachers and to share experiences and emotions (community of practice).

The intervention was a three-hour role-play-based seminar. It was held in the first quarter of the academic year 2024–2025 and provided thrice. It consisted of three sections:

- –

An introductory part (30 min) where the seminar activities were explained, groups for the role-plays were organized, and the observation tools were distributed and explained.

- –

A core part (120 min) consisted of a model video showing the difference between a disease-centered and patient-centered interview, role-playing, and immediate feedback in small groups.

- –

A final part (30 min) consisted of a general group debriefing followed by individual reflective writing.

The seminar occurred in the fifth year of the Medical Faculty at a Spanish University. It was mandatory for students in the Geriatrics course (Medicine and Surgery VI block). Students are familiar with the role-play technique, usually used with a biomedical orientation to diagnosis and clinical reasoning.

ParticipantsAll forty-six students in the 2024–25 academic year in the geriatrics course participated in the seminar. Five teachers with expertise in clinical communication were involved: three geriatricians, one occupational therapist, and one nurse. The first author (a geriatrician with training in health professions education) supervised its execution. Two additional external academic observers took notes on its implementation.

Data collectionThe following qualitative data were collected:

- •

The students' written reflections.

- •

Semi-structured individual interviews with three students, one from each session.

- •

Semi-structured focus group interview with five teachers.

- •

Observations of two academic supervisors who were not involved in teaching roles.

The recorded interviews were transcribed. These transcripts and the students' written reflections were thematically analyzed using a mixed theory and data-driven approach, using as sensitizing concepts: situated learning, reflection, the community of practice, DPC, trust, empathy, and PCC. Three investigators (CN and two external) initially read and coded qualitative data independently. Initial themes were then shared and iteratively further developed by the whole team.

ResultsWritten reflectionsForty-four students completed the written reflection (two had to leave after the general debriefing and could not complete it).

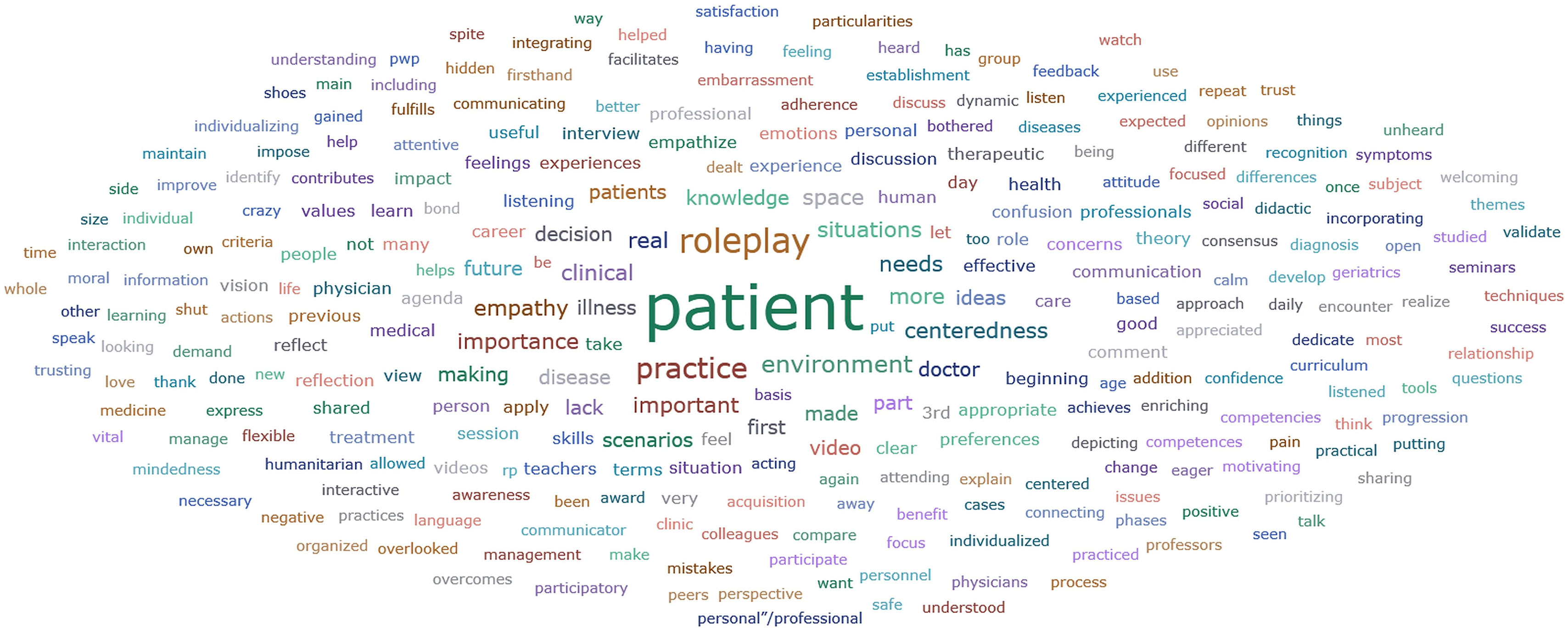

A data cloud of concepts is shown in Fig. 1:

Thematic analysis of the written student reflections yielded four themes:

Students learned from being actively involved in role-playing and debriefingFor students, role-playing was a key element: “it is an approach that is rarely dealt with during a career [for teaching DPC]” (WR8). They recommended continuing with this approach: “It is important to have this type of role-playing during study, especially in geriatrics, a very human specialty” (WR2); “It should be kept as part of the subject as it can be even more instructive than the theory itself” (WR19).

They commented on the value of “seeing and representing different scenes” (WR19), “putting themselves in the role of the patient” (WR18), and “having the space to be a doctor, talking to the patient and learning to communicate better” (WR15). They said “it has been very interactive and a source of discussion and debate” (WR34), “commenting on our peers' role-plays, expressing our opinions and sharing our experiences” (WR25), with “peers and teachers.” (WR17).

Safe learning atmosphere and teacher-guidance are requirements for learningStudents indicated that psychological safety is essential. They emphasized the “quiet and safe” (WR4) learning atmosphere, “with a lot of listening on the part of all” (WR19). “Trust achieved” (WR16), “puts embarrassment aside” (WR19), and “gives you room to make mistakes” (WR16).

The role of teachers emerged as fundamental: “… above all, by the professionals who teach it” (WR16); for example, explaining the roles in a scenario “to each person separately” (WR15), “being very attentive …, conveying the important ideas clearly and […] being very eager for us to learn” (WR14). Students valued sharing experiences and concerns with teachers: “That's how knowledge comes to me” (WR26). The efforts of the teachers were recognized and appreciated: “I am very grateful for how you have done it, I can tell it is made with a lot of affection. Thank you very much for everything” (WR7).

The importance of skills and attitudes related to DPC, PCC, and empathyStudents referred to both skills and attitudes: “It's great that we're learning how to diagnose pneumonia, but it's critical to know how to communicate it, what it means to the patient, and what I can do to help them” (WR5). But also: “The impact our attitudes can have on the person and the treatment” (WR6). They detected the importance of “not focusing like mad on knowing all the theory” (WR35) and, instead, “creating a bond and a safe space for the patient …, letting the patient talk” (WR18). They saw “the differences … between the more disease-oriented view and the more person-oriented view” (WR9), and they gave priority to the second: “We need to understand that people are not just diseases, but rather ‘a whole’: feelings, values, experiences, preferences, etc.” (WR23).

Students expressed that these are often lacking in the clinical practice setting: “communication, verbal and nonverbal, is often overlooked in clinical practice” (WR15), and “ there is a great need for health professionals to put it [the more PCC vision] into practice” (WR9). Learning to make this connection with patients “is much more important than one might think” (WR19).

Students perceive DPC, PCC, and empathy as core values of the professionStudents appreciated DPC, PCC and empathy as “vital to be a good doctor” (WR8) and important “to do well in the profession” (WR12) because they believed these are not only necessary skills and attitudes but also core values of the profession: “I have learned to incorporate new ideas into the construction of my personal criteria, how the relationship with the healthcare professional can impact the patient's health and personal life” (WR25). They saw the seminar as relevant to their practice: “It has been very enriching because it has taught me to consider the patient's opinion, values, and preferences, and I will apply it in my clinical practice. It will be present in my work and daily practice” (WR41). And they made a connection with their motivational anchors: “by applying what we have learned, we may never get recognition or a theoretical award, but we will get a relationship with patients that not everyone gets, and that is what I find most fulfilling” (WR8).

Interviews with participantsInput from participants was gathered during one focus group interview with all five teachers (45 min) and three individual interviews with participating students (24, 14, and 143 min, respectively). We also reviewed the observers' interview notes.

Analysis of these data confirmed the findings of the analysis of the students' reflections. In the interviews, students said they had used role-playing only to learn theoretical material and never before to learn DPC” (S1). Teachers saw that “theory only goes so far, but when you put yourself in the scene, it is when you internalize … you are aware of the difficulty of communication” (T4). And “more than what I have to do, it's about things I shouldn't do … Wow, it made me feel bad to say, wow, I don't have to do these things. It is not the same thing you are told; it is that you see it represented. Because it hits you a lot harder and sticks a lot more” (S2).

Students also pointed out they learned by “having several scenarios, watching some videos …, practicing and observing role-plays … and comparing … which are essential to seeing how these things can be done better” (S1).

Teachers and students explained how acting as doctors and patients and observing peers and actors were all useful. “One student told the group that she had become so immersed in her role as the doctor that she leaned toward the patient and felt like she was him. She said that this had never happened to her before.” (T1) and “Well, with the pain, in Pablo's case, the girl got so much into the role that she started to shake” (T2).

Students also discussed the value of observing others and discussing this afterward: “Especially to see it, because … when you see it from the outside, you see it better than when you are inside … It's enriching“ (S2). And: “what helped me the most was the discussion with my classmates … you reflect, but your colleagues may reflect differently; some are common, and some are not. So, it enriches you” (S3).

Participants appreciated seeing a patient-centered versus disease-centered attitude in the video. “I was surprised by the additional use of video viewing” (S3), and teachers found it extremely “efficient as students concluded naturally… when they saw the patient-centered part ” (T4).

Students also talked about the role of the teacher in “creating a fairly safe space” (S2) and in “guiding …the necessary, essential, and enriching” final reflection with peers and teachers (S1). Always ensuring “that it comes out of us (…) that it comes out of us first of all” (S1). And teachers explained how they empowered students: “I'm not judging you, okay” (T2), how they guided students to focus on communication, PCC and empathy: “So I insisted, I'm not a doctor, I'm not very interested on diagnosis, I'm interested in other things…” (T2). They highlighted the relevance of “the relation between them [students and teachers]”, of being “united… to transmit the information” (T3).

Both teachers and students (T2 and S3) discussed the importance of group size: groups should be big enough to invite plural perspectives, but small enough to allow everyone to participate.

Students commented on the seminar's impact on them, “And it made me think a lot. I mean, I went home thinking, wow (…) And that [a detail of the seminar] was the first thing I said when I got home” (S3). They emphasized how the seminar had helped them and how they would incorporate what they had learned into their work: “You think of a chronic complex patient who has many pathologies, and you say, I have no idea where to begin, or what is more important, or… I should ask him his preferences … and I have a more integral vision of the patient” (S2). And: “Yes, one hundred percent (…) So I think it's super important; I mean, one hundred percent, I'm going to apply it in everything!” (S3). Teachers said students will apply what they have learned to their clinical practice: “I think so” (T2), “some will use it” (T5), “nonverbal language…” (T4).

External observers emphasized the impact of individualizing role-playing and the effect of seeing how others role-play. Despite the organizational effort it has represented, teachers and observers are eager to maintain it.

DiscussionThis study shows how a micro-level CA-based communication training intervention can help medical students understand the importance of PCC and empathy. Applying design principles of reflection, situated learning, and community of practice of CA theory, we designed and implemented a 3-h seminar consisting of role-playing, debriefing, and reflection writing for 5th-year medical students.

Our analysis shows that students could practice skills related to PCC and empathy through active participation, discussion, and facilitated reflection. Students reported improved awareness and attitude related to these skills.

And they also saw these as values of the medical profession and clearly verbalized their intention to apply what they learned in their daily practice.

Even with one small intervention, we have created a sense of community of practice, where students actively reflect, communicate, and engage in activities, exhibiting a sense of ownership characterized by personal investment and mutual dependency.14,19 It is essential to engage students actively to execute the same type of task,15 and they describe how connecting with peers and teachers fosters collaborative problem-solving and promotes intrinsic motivation.14,16,20–22

The effectiveness of applying CA principles to develop medical students' knowledge, skills, and attitudes has already been reported.16,23 In this study, students explain how the seminar encouraged them to view PCC and empathy as essential medical profession values. Role modeling may have been an important factor, since it has been shown to impact learning about DPC24 and empathy.25 Another possible factor was that students experienced the importance of empathy when playing the role of a patient.25,26 Learner support26 and evoking their emotional responses in the group discussions may also have promoted values around PCC and empathy.27,28

Based on this study, we have advice for those designing similar micro-level interventions.

First, do not wait until you have all the necessary resources. Even a short seminar can have a valuable impact.

Use a systematic design based on learning theory. Collaborate closely with the teachers involved. Design a variety of authentic role-play scenarios. Create a safe learning atmosphere. Students should also take on the roles of both patients and active observers. Guide group discussions. And allow time for individual reflective writing.

The main strength of this study is that we designed and implemented an educational intervention in an actual medical curriculum with limited resources. The intervention stands out for being provided by an interprofessional team, even though all the medical teachers were geriatricians. Our study has limitations. First, it is limited to 5th-year students at one teaching unit, so we cannot extrapolate results to other populations. Second, conducting interviews with more students, such as in focus groups, would have been interesting, but we could not do so due to practical issues and the academic calendar. Third, our data give insight into how participants experienced the seminar, but we do not know if and how students will change their behavior. Future research should examine the duration of the effect over time and the impact on other populations.

Ethical considerationsThe Ethical Review Board (ERB) committee of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona decided that this research did not require additional ERB approval (e-mail, d.d. March 18, 2024), because it does not directly involve personal data, material of human origin, or experimental animals. Participation in the seminar was performed in the context of a regular academic course. Students were informed that learning results would be analyzed for seminar improvement, the voluntary submission of the reflections and participation in the interviews would not affect their academic results, and their data would only be used anonymously and confidentially. Students were explicitly told that they could withdraw without consequences. According to the current legislation in Spain regarding Privacy Protection,18 interviewed students and teachers were asked for written informed consent to be audio recorded for transcription and analysis. After transcription, the audio recordings were destroyed, and any personal data or data that could be linked to the identity of participants was removed. Consent forms, anonymized transcripts, and reflections were restored digitally on a protected university server under a password known only to the researchers. They will be kept for five years and then destroyed.

FundingThe authors declare that this research received no specific funding from public, commercial, or nonprofit funding agencies.

Other considerationsThis study is part of the unpublished thesis for the International Master of Health Professions Education at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, which the first author obtained in July 2025.

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

I am grateful to Dr. Whittingham for her guidance and support during the International Master's in Professional Health Education program at Maastricht University, Netherlands, which made this publication possible.