This scoping review aims to explore the current utilization of technologies in teaching clinical nursing skills, identifying the employed technologies and technological features in nursing education. Following the Arksey and O'Malley framework, this review systematically identified and analyzed relevant literature across various databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, and CINAHL. The search strategy encompassed articles published from 1995 to August 2023, with a focus on educational technologies in nursing clinical education. The review adhered to the PRISMA-ScR checklist and the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual. A total of 58 studies were included, spanning from 1995 to 2023, with a geographical distribution across multiple countries. The majority of studies involved nursing students, with a variety of methodologies and data collection methods employed. The review identified several types of technology used, such as social media, online web-based courses, mobile applications, educational videos, virtual reality, serious games, and e-simulation. These technologies were applied in diverse areas of nursing education, including premature infant care, stroke patient care, airway care, and basic nursing skills. This scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of the technological landscape in nursing clinical education, informing educators, policymakers, and practitioners about the available resources and their potential to improve nursing education and patient care.

Este estudio de alcance tiene como objetivo explorar la utilización actual de las tecnologías en la enseñanza de habilidades clínicas en enfermería, identificando las tecnologías empleadas y las características tecnológicas en la educación en enfermería. Siguiendo el marco de Arksey y O'Malley, esta revisión identificó y analizó sistemáticamente la literatura relevante en varias bases de datos, incluidas MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus y CINAHL. La estrategia de búsqueda abarcó artículos publicados desde 1995 hasta agosto de 2023, con un enfoque en las tecnologías educativas en la educación clínica en enfermería. La revisión se adhirió a la lista de verificación PRISMA-ScR y al Manual de Revisores del Instituto Joanna Briggs. Se incluyeron un total de 58 estudios, que abarcaron desde 1995 hasta 2023, con una distribución geográfica en múltiples países. La mayoría de los estudios involucraron a estudiantes de enfermería, con una variedad de metodologías y métodos de recolección de datos empleados. La revisión identificó varios tipos de tecnología utilizados, como redes sociales, cursos en línea basados en la web, aplicaciones móviles, videos educativos, realidad virtual, juegos serios y e-simulación. Estas tecnologías se aplicaron en diversas áreas de la educación en enfermería, incluidos el cuidado de bebés prematuros, el cuidado de pacientes con accidente cerebrovascular, el cuidado de las vías aéreas y las habilidades básicas de enfermería. Este estudio de alcance proporciona una visión general completa del panorama tecnológico en la educación clínica en enfermería, informando a educadores, responsables políticos y profesionales sobre los recursos disponibles y su potencial para mejorar la educación en enfermería y la atención al paciente.

Nurses are vital to healthcare, significantly impacting its quality and advancement.1 Competent nursing practice ensures safe, evidence-based, and patient-centered care.2 Clinical practice is essential for developing nursing competence.1

Nursing education programs must meet professional standards by integrating essential knowledge, skills, and attitudes.2 Theoretical foundations, competency-based training, and practical experiences prepare students for clinical roles.3

Traditional lecture-based methods face challenges, including resource demands and limited engagement.4 Students also report dissatisfaction with clinical supervision and support,5 leading to missed learning opportunities.6 Innovative teaching approaches are needed to address limited clinical exposure.7

Evolving traditional methods is crucial for enhancing learning. Strategies incorporating hands-on experiences and interaction promote meaningful learning.4 Information technology offers transformative potential,8 with universities leveraging it to enhance medical education.1 Technology's flexibility and cost-effectiveness facilitate integration into clinical settings, driving innovation.9 Digital technologies are reshaping nursing education, with telehealth, mobile devices, and virtual reality becoming integral.10

E-learning has proven successful in teaching various nursing concepts and skills,11 influencing knowledge, behavior, and performance. Integrating educational technologies into clinical skills teaching is resource-intensive but critical.

MethodologyThis scoping review followed Arksey and O'Malley's five-stage framework12 and adhered to the PRISMA-ScR checklist13 and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewers' Manual.

Inclusion criteria: original studies in health higher education settings examining technology use for teaching clinical nursing skills to nursing students or nurses, published between January 1995 and September 2023, with available full text, and original research using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods.

Exclusion criteria: editorials, conference papers, reports, and theses; studies using traditional, non-electronic methods; studies not involving nursing students or nurses; and studies examining technology use for subjects other than clinical nursing skills.

The review addressed the following questions:

- 1.

What are the current educational technologies in nursing clinical education?

- 2.

What technological features are utilized in nursing clinical skills education?

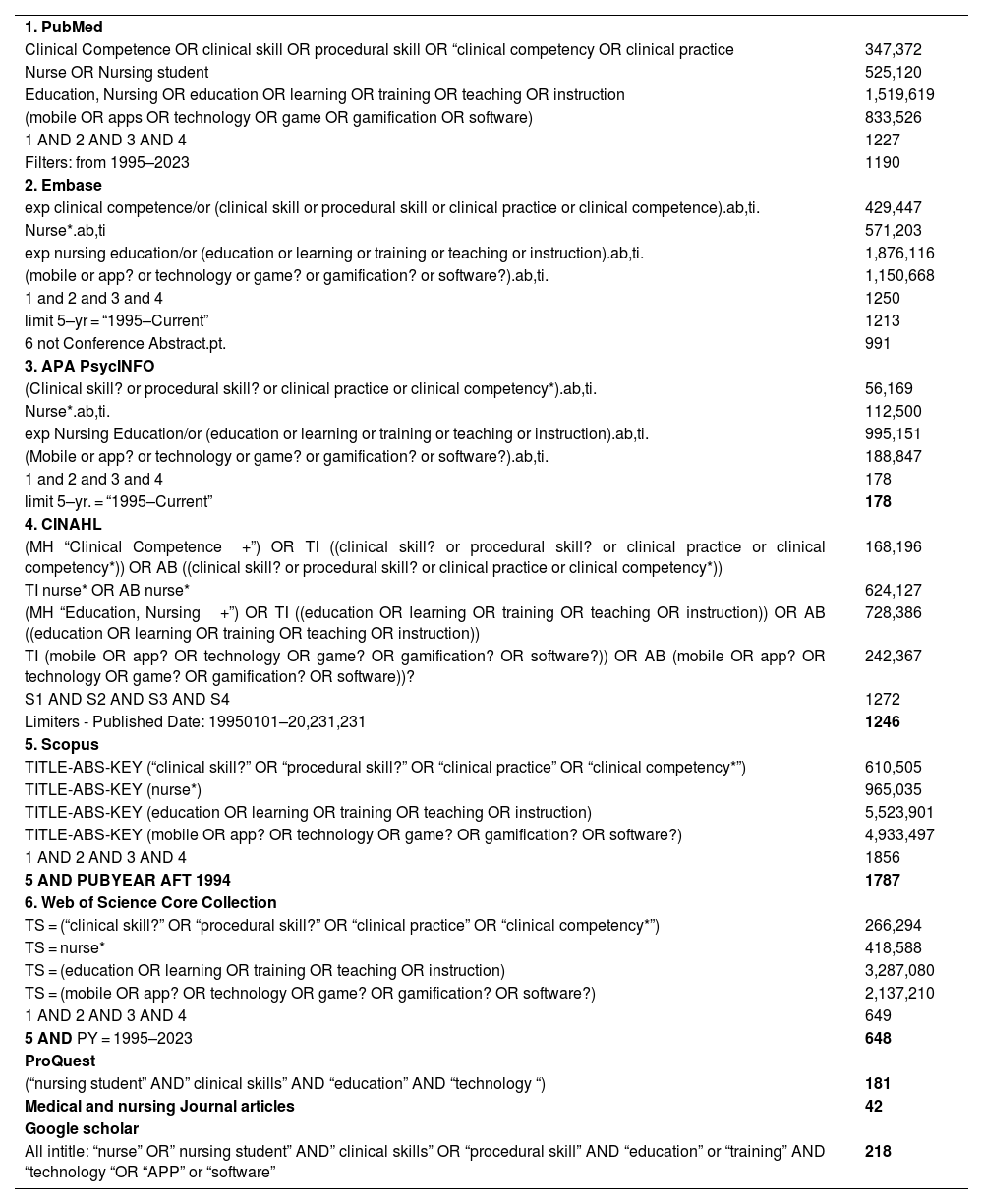

MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), CINAHL, ERIC, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar were searched, including medical education journals. Reference lists were also manually searched. The search was completed in August 2023 by a librarian (Search strategy detailed in Table 1).

Databases, search strategy and number of retrieved studies.

| 1. PubMed | |

| Clinical Competence OR clinical skill OR procedural skill OR “clinical competency OR clinical practice | 347,372 |

| Nurse OR Nursing student | 525,120 |

| Education, Nursing OR education OR learning OR training OR teaching OR instruction | 1,519,619 |

| (mobile OR apps OR technology OR game OR gamification OR software) | 833,526 |

| 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 | 1227 |

| Filters: from 1995–2023 | 1190 |

| 2. Embase | |

| exp clinical competence/or (clinical skill or procedural skill or clinical practice or clinical competence).ab,ti. | 429,447 |

| Nurse*.ab,ti | 571,203 |

| exp nursing education/or (education or learning or training or teaching or instruction).ab,ti. | 1,876,116 |

| (mobile or app? or technology or game? or gamification? or software?).ab,ti. | 1,150,668 |

| 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 | 1250 |

| limit 5–yr = “1995–Current” | 1213 |

| 6 not Conference Abstract.pt. | 991 |

| 3. APA PsycINFO | |

| (Clinical skill? or procedural skill? or clinical practice or clinical competency*).ab,ti. | 56,169 |

| Nurse*.ab,ti. | 112,500 |

| exp Nursing Education/or (education or learning or training or teaching or instruction).ab,ti. | 995,151 |

| (Mobile or app? or technology or game? or gamification? or software?).ab,ti. | 188,847 |

| 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 | 178 |

| limit 5–yr. = “1995–Current” | 178 |

| 4. CINAHL | |

| (MH “Clinical Competence+”) OR TI ((clinical skill? or procedural skill? or clinical practice or clinical competency*)) OR AB ((clinical skill? or procedural skill? or clinical practice or clinical competency*)) | 168,196 |

| TI nurse* OR AB nurse* | 624,127 |

| (MH “Education, Nursing+”) OR TI ((education OR learning OR training OR teaching OR instruction)) OR AB ((education OR learning OR training OR teaching OR instruction)) | 728,386 |

| TI (mobile OR app? OR technology OR game? OR gamification? OR software?)) OR AB (mobile OR app? OR technology OR game? OR gamification? OR software))? | 242,367 |

| S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 | 1272 |

| Limiters - Published Date: 19950101–20,231,231 | 1246 |

| 5. Scopus | |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY (“clinical skill?” OR “procedural skill?” OR “clinical practice” OR “clinical competency*”) | 610,505 |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY (nurse*) | 965,035 |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY (education OR learning OR training OR teaching OR instruction) | 5,523,901 |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY (mobile OR app? OR technology OR game? OR gamification? OR software?) | 4,933,497 |

| 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 | 1856 |

| 5 AND PUBYEAR AFT 1994 | 1787 |

| 6. Web of Science Core Collection | |

| TS = (“clinical skill?” OR “procedural skill?” OR “clinical practice” OR “clinical competency*”) | 266,294 |

| TS = nurse* | 418,588 |

| TS = (education OR learning OR training OR teaching OR instruction) | 3,287,080 |

| TS = (mobile OR app? OR technology OR game? OR gamification? OR software?) | 2,137,210 |

| 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 | 649 |

| 5 AND PY = 1995–2023 | 648 |

| ProQuest | |

| (“nursing student” AND” clinical skills” AND “education” AND “technology “) | 181 |

| Medical and nursing Journal articles | 42 |

| Google scholar | |

| All intitle: “nurse” OR” nursing student” AND” clinical skills” OR “procedural skill” AND “education” or “training” AND “technology “OR “APP” or “software” | 218 |

Studies were imported into EndNote X20, and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers, blinded to each other, screened titles, abstracts, and full papers based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. Additional articles were identified from reference lists. Studies from 1995 onward were included due to the advent of fourth-generation distance education and broadband internet.

Data extraction followed the JBI approach14 by two independent, blinded researchers. A data extraction tool captured key information, refined through consensus after reviewing the first five studies. Extracted information included: authors, year and type of publication, location of studies, study population, major of students, study design, aim of study, and dimensions and components of student support (Table 2). A total of 58 documents were deemed relevant (summarized in Additional File 1).

Types of technologies used in nursing education.

| Type of technology | Authors | Number of Studies | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social media(multimedia) | P. Anand 2021, Ş. Bilgiç 2021, M. M. Ghahfarokhi 2022, M. Motamed-Jahromi 2022, A. K. Vicdan 2020 | 5 | 8.6 |

| Online web-based course | L. Atack 2008, M. Barisone 2019, A. Erol 2020, S. Gerdprasert 2010, S. Gerdprasert 2011, D. Öztürk 2014, R. Sheikhaboumasoudi 2018, V. E. C. Sousa Freire 2018 | 8 | 13.7 |

| Mobile application | C. R. A. Baccin 2020, S. B. Bayram 2019, H. Y. Chang 2021, C. J. Ho, 2021, L. L. Hsu 2019, X. L. Huang 2021, S. Jonassen 2021, J. Kang 2018, H. Kim 2018, S. J. Kim 2017, Y. Kurt 2021, M. Radmard 2021, I.-Y. Yoo 2015 | 16 | 27.5 |

| Educational videos | A. Bahar 2017, A. F. Cardoso 2012, J. P. C. Chau 2021, Y. H. Chuang 2018, E. G. İsmailoğlu 2020, N.-J. J. Lee 2016, Heji Mohammad Nourozi 2013, C. Catling 2014 | 8 | 13.7 |

| Virtual reality | M. S. Bracq 2019, K. R. Breitkreuz 2021, H.-Y. Chan 2021, M. A. Rushton 2020, H. Singleton 2022, P. C. Smith 2015,G.Mirzayan 2023, J. Y. Wong 2022, S. Y. Yang 2022, S.J. | 9 | 15.5 |

| Serious game and web-based game | A. Calik 2022, H. M. Johnsen 2016, A. J. Q. Tan 2017, A. Blanié 2020, N. F. Cook 2012, D. Stanley 2011, Wright 2022 | 7 | 12 |

| Augmented reality | C. Rodríguez-Abad 2022 | 1 | 1.7 |

| E-book | S. T. Chuang 2022 | 1 | 1.7 |

| Virtual patients | M. Peddle 2019 | 1 | 1.7 |

| E-simulation | F. E. Bogossian 2015, S. D. Reyes 2008 | 2 | 3.4 |

| Sum | 58 | 100 |

A descriptive, analytical approach was used to collate, summarize, and categorize the literature, incorporating quantitative (numerical counts) and qualitative (template analysis) methods. Descriptive data tables were created, followed by template analysis,15 involving familiarization, preliminary coding, a priori themes, and an iterative refinement process. The final template was applied to the entire dataset.

ResultsThe results are presented in two sections: first, an overview and descriptive summary of the included studies; and second, an examination of the current educational technologies in nursing clinical education.

Descriptive summary of the included studiesThe search strategy identified relevant studies from multiple databases. After removing duplicates, a total of 342 studies were screened based on their titles and abstracts. Of these, 284 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g., were not original research, did not focus on clinical nursing skills, and were not conducted in the relevant setting). The remaining studies were retrieved for full-text review. After a full-text review, 58 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in this scoping review.

This review encompassed 58 studies published between 1995 and 2023, comprising 56 articles. The distribution of studies over time showed that 3 studies (5.1%) were published between 2006 and 2010, 21 studies (36.2%) between 2016 and 2020, and 24 studies (41.3%) between 2021 and 2023. Geographically, the studies originated from various countries, with single studies from India, Canada, Italy, Spain, and Norway, two studies each from Brazil, France, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Singapore, three from the United Kingdom, four from Australia, five from South Korea, six from the United States, seven from Taiwan, eight from Iran, and ten from Turkey.

The majority of the research, 81%, involved nursing students as participants, while 17% included nurses and other healthcare professionals, and 2% focused on nursing educators. All studies concentrated on undergraduate nursing students, with no studies including participants from master's or doctoral nursing programs. Methodologically, the studies consisted of 46 quantitative, 3 qualitative, 8 mixed-methods, and 1 with an unspecified methodology. Data collection methods varied, with questionnaires used in 38 studies, open-ended queries in 7, checklists in 13, multiple-choice questions in 15, Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE) in 5, interviews in 2, and Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS) in 2.

Current educational technologies in nursing clinical skills educationThe types of technology used in nursing clinical skills education, as indicated by the included studies, were as follows: mobile applications (27.5%), online web-based courses (13.7%), educational videos (13.7%), virtual reality (15.5%), serious games and web-based games (12%), social media (8.6%), e-simulation (3.4%), airway care (3.4%), augmented reality (1.7%), e-books (1.7%), virtual patients (1.7%), and the use of traditional methods (1.7%) (Table 2).

The areas of technology application in nursing clinical skills education included basic nursing skills (injections, catheterization, wound care, drug administration) (43.1%), non-technical care (problem-solving, communication, teamwork, decision-making, leadership) (18.9%), infection control and patient safety (5.1%), cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) (5.1%), physical examination (5.1%), childbirth and related care (3.4%), airway care (3.4%), care during hemodialysis (1.7%), stroke patient care (1.7%), care of the patient under mechanical ventilation (1.7%), type 2 diabetes patient care (1.7%), chest tube care (1.7%), chronic disease care (1.7%), preparation of craniotomy table equipment in the operating room (1.7%), and premature infant care (1.7%).

DiscussionThis study identified and analyzed technological features used in teaching clinical nursing skills, synthesizing research and highlighting knowledge gaps. A review of 58 articles and theses (1995–2023) revealed that technology enhances learning through easy information access, content repetition, and knowledge consolidation. Key technological features were categorized into seven areas: content, accessibility, environment, usability, pedagogical approaches, security, and ethical considerations.

Content: Effective educational content should be engaging, tailored to learning styles, standardized, updated, and sourced from credible references. Realistic, interactive scenarios simulating clinical environments are crucial. Online platforms facilitate continuous access to updated information.16 Simulated scenarios enhance clinical assessment, while video-based education reduces exam anxiety and increases satisfaction.17

Accessibility: Mobile-based, web-based, and social media tools are transforming learning, with mobile learning supporting higher education through accelerated skill acquisition, cost-effectiveness, and self-directed study.18,19 Orthopedic trainees improved clinical pattern recognition and motor skills via electronic education, and smartphone use enables flexible learning.

Environment: Immersive, realistic, and interactive environments, such as virtual simulations and VR, increase student satisfaction, confidence, and skills.20 VR training fosters deep learning,21 and motivates continuous practice.22 However, VR involves costs, technical complexity, and potential discomfort. Ethical concerns like misuse and dependency require careful consideration.23

Usability: Ease of access, affordability, flexibility, and self-paced learning are key. Technology reduces waste, allows repeated skill rehearsal, and fosters technological skills and collaboration.24 Smartphone-based tools offer non-judgmental practice environments.

Pedagogical approaches: Technologies support collaborative, active, problem-based, and case-based learning, promoting engagement and knowledge sharing.21 Active learning, such as simulation-based recognition of patient deterioration, improves performance. Gaming and inquiry-based methods enhance knowledge retention and clinical reasoning.25 Virtual simulation positively impacts learning outcomes, but technical issues can cause frustration.22 Strategies to manage cognitive load are recommended.26 Mobile technology and instructional videos enable repeated review and skill replication.

Security and ethical considerations: Protecting privacy and data security is paramount, including safeguarding personal information, respecting intellectual property, and ensuring equitable access. Ethical concerns associated with VR include addiction, surveillance, and manipulation (36), along with misuse, peer pressure, and data collection.27

ConclusionThis research was undertaken with the objective of identifying and analyzing technological features used in the instruction of clinical skills. By reviewing educational technologies in nursing skills training as a broad topic, rather than focusing on a single technology, this study informs nursing educators about the available resources. Nursing educators and faculty can identify studies that align with their resources and skills and can be implemented in their workplaces. It may also motivate educators to utilize more than one technology in their teaching or to combine different technologies with more traditional tools to achieve optimal learning outcomes for various student learning approaches, thereby reducing learning barriers in this domain.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThe present work has received approval from the ethical review board of Urmia.

University of Medical Sciences (Ethical No. IR.UMSU.REC.1401.490).

FundingThis study was not granted by any public or private funding sources.

Declaration of competing of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.