There are four objectives to this paper: (1) To determine whether undergraduates enrolled in Health-Sciences studies agree with the use of human stem cells for medical research, treatment and genetic uses. (2) Whether they would consider the use of pre-implantation-embryos for medical research. (3) Whether attitudes toward the previous two issues are linked to gender, field of study, transcendental/spiritual convictions and political biases. (4) A panel of discussion will modify their opinion.

ResultsThe present study shows that, before attending a discussion panel session, media was the main source of information that the students had on the surveyed topics. A discussion panel was useful for clarifying respondents’ opinions on the explored items. Significantly, the discussion panel had an influence on those respondents who did not have a formed opinion on the explored items.

ConclusionsA discussion panel is a convenient, but limited tool, in the shaping of undergraduate opinions on ethically controversial scientific matters.

Los objetivos de este artículo son conocer si: 1) los estudiantes de pregrado matriculados en titulaciones de grado de ciencias de la salud están de acuerdo con la utilización de las células madre humanas para la investigación médica de los embriones preimplantatorios, la cura de enfermedades y los usos génicos; 2) consideran el uso de los embriones preimplantatorios humanos para la investigación; 3) las actitudes hacia los 2 temas anteriores están relacionadas con el género, el grado universitario en curso, la afiliación política y las convicciones trascendentales o espirituales, y 4) conocer si un panel de discusión, con expertos, modifica esas opiniones.

ResultadosLos resultados del presente estudio mostraron que antes del panel de discusión, los medios de comunicación eran la principal fuente de información de los encuestados sobre los temas estudiados. El panel de discusión fue útil para aclarar las opiniones de los encuestados, aprobar o desaprobar los ítems explorados. Significativamente, el panel de discusión influyó en los encuestados que dijeron que no tenían una opinión formada sobre los ítems explorados antes del panel de discusión.

ConclusionesEl panel de discusión es una herramienta conveniente pero limitada en la formación de las opiniones de los estudiantes de pregrado en titulaciones de ciencias de la salud sobre cuestiones científicas éticamente controvertidas.

Scientists belong to the society of their time. Science is influenced by common social values, but in turn science modifies them.1 New scientific discoveries may confront established moral principles.2 When this happens, it takes time and considerable discussion in order to create a new consensus. Two controversies are models of a new moral dilemma: stem cells and preimplantation-embryos.

As an introductory example of these controversies, we can turn to the personal experience of Dr Shinya Yamanaka. In an interview with the New York Times,3 he declared that he became interested in stem cell research when he observed a human embryo under the microscope: “When I saw the embryo, I suddenly realized there was such a small difference between it and my daughters,” said Dr. Yamanaka… “I thought we can’t keep destroying embryos for our research. There must be another way.” This meant that there was a personal moral reason, not only scientific, for Yamanaka to start his research. This fact is hardly compatible with the arguments that ethics negatively influences scientific development as popularized by John William Draper in his book History of the Conflict between Religion and Science and whose theories have been discredited in the last thirty years by historians and sociologists.4

Stem cells (SCs) are undifferentiated cells that can produce more stem cells and eventually differentiate into specialized cells in living organisms. This allows for the regeneration of body cells and tissues that can be used for therapeutic approaches to diseases, previously incurable by other means. Knowledge about SCs comes from the implementation of numerous methods.5,6 These methods have provided a multitude of scientific advances in the last decades. In mammals, there are three broad types of SCs: 1: embryonic stem cells (ESCs), 2: adult stem cells (ASCs) and 3: induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). For this study iPSCs7 have not been considered since their ethical implications are not the same as ESCs or ASCs, and these two cell types will be grouped generically as Stem Cells (SC).

Although additional research is needed, ESCs and ASCs are already useful tools for drug development and disease modeling. One main concern, but not the only one regarding therapeutic usage of all types of SCs, is that they can lead to malignant cell lines in addition to normal cells. If scientists can reliably direct the differentiation of ESCs and ASCs into regular specific cell types, they may be able to use the resulting, differentiated cells in cell-based therapies. Yet efficiency in the development of tissue culture in the laboratory, the utility of regenerative medicine and ethical and legal implications are different for human ESCs and ASCs.8

Another controversy is that of preimplantation-embryos.9 The 1984 Warnock Report10 limits experimentation on human embryos up to the end of the fourteenth day after fertilization. The biological criterion on which this statement is based is twofold: the completion of embryo implantation into the uterus and the appearance of the primitive streak.11 The primitive streak is a surface thickening that gives an axis for development and prevents future twining or merging. This criterion defines the pre-embryo or preimplantation-embryo12 (hereafter termed preimplantation-embryo).

In parallel to the development of research on these issues, a strong scientific-social discussion has been generated. These issues are not free from controversy since they clash with non-epistemiological values that could influence the development of rational decissions.13 Ethnical, religious, political, economical and biological aspects are intertwined.14–17

Opinion studies have been carried out in order to explore the point of view of these different groups on the use of human SCs and preimplantation-embryos. These studies include the opinions of adult general population in different countries and collectives.18–23

The support of USA residents 18 years of age and older to human-SC research is slightly higher in males (64%) than in females (57%), and rises sharply with level of education, from 53% among those with a high-school degree to 69% among those with a college major.18 Such support for human-SC research also increases if the research centers are public and financed with public funding.24 Other determining factors for the responses are the political and religious contexts.25–29 Youth's and specifically science-students’ opinion has been less studied. In college cohorts, the effects of frames, background science and SC source were examined in relation to ethics, credibility and usefulness of human-SC research and therapeutic application. Results from a study on college-graduates’ opinion suggest that science majors perceive human-ESC research as more ethical, more credible in an economics-context frame and more useful, except in a conflict-frame than non-science majors do.30

A discussion with experts with diverse points of view can be used to develop the knowledge on a controversial topic. The discussion can be helpful to develop critical thinking being more effective than giving just a lecture.31,32 In view of the dearth of information we have designed this study to reach manifold goals. First: to consider the self-confessed knowledge of health science undergraduate students about research and application of human SCs and preimplantation-embryos. Second: to discern whether this opinion will change after consultation with a panel of discussion. And third: to know if their opinions are linked to the student's socio-cultural demographics.

Materials and methodsA transversal study, pre–post intervention study, has been carried out in a cohort formed by health sciences undergraduate students. All of these undergraduates attended a panel of discussion related to stem cells and their therapeutic implications.

ConfigurationThe present study was conducted during the celebration of the “National Congress of Undergraduate Students for Research on Health Sciences”. This conference is celebrated yearly at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM), Spain, since 2006.33 During the sessions it was organized a panel of discussion. The panel, besides clarifying the differences between ESC and ASC, talked about human-SC efficacy in experimental therapy and its current applications in clinics. They also explained the possible mechanisms of action of human-SC at injured areas. The panel of discussion content is available at: http://complumedia.ucm.es/resultados.php?contenido=U8wMsNnHqL-fimeOJyZejw.

MethodThe study includes a self-administered questionnaire composed of two identical sets of questions (Supplementary data). The first set of questions was to be answered before attending to a panel of discussion and the second after attending to the panel. Both sets were collected together. Questionnaires were distributed and collected by hand. Previously this questionnaire had been validated on 40 students. Students’ participation was voluntary and anonymity was guaranteed. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the San Carlos Clinical Hospital of Madrid.

Statistical analysisFirst, a statistical analysis of the demographic variables and questionnaire answers was performed in which the relative frequencies of qualitative variables, average and standard deviation of quantitative variables were obtained. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test. When the χ2 test was not suitable, because the frequency of any of the cells was less than 5, Fisher's exact test was employed. In both cases, differences were considered significant when p-values were ≤0.05 (95% confidence level). Finally, the opinion changes in questionnaire responses were evaluated before and after the conference, by using the Mc Nemar's test. If this index had a value <0.4, it was considered that the conference had influence on the opinion changes. The information was processed by using the Excel package. The statistical package used was the SPSS® v.23.0.

ResultsTwo hundred questionnaires were distributed to attendees to the panel of discussion. One hundred and twenty seven replies were collected, for an overall response rate of 63.5%. Of this total, 111 were from females (87%) and 16 were from males (13%), altogether with an average age of 22±4 years. Out of the total number of respondents, 15% were students of Pharmacy, 14% of Medicine, 13% of Human Nutrition & Dietetics, 38% of Optic, 2% of Podiatry, 1% of Psicology, 3% of Occupational Therapy, 8% of Veterinary Medicine and 6% did not classify themselves.

Popular knowledge about human SC and human preimplantation-embryoNinety percent of respondents considered that the general population had not enough information about research and usage of stem cells and preimplantation-embryos. This response had no significant statistical difference related to degree, gender, etc.

Health-sciences student's knowledge about SC- •

Pre-panel of discussion. Thirty-one percent of the respondents (47% of the males and 29% of the females) declared to have knowledge on this topic before listening to a panel of discussion. They informed that their principal source of information about the subject had been mass media (50%)—television (27%), press (20%) and radio (3%)—followed by college academic activities (26%) and the Internet (20%).

- •

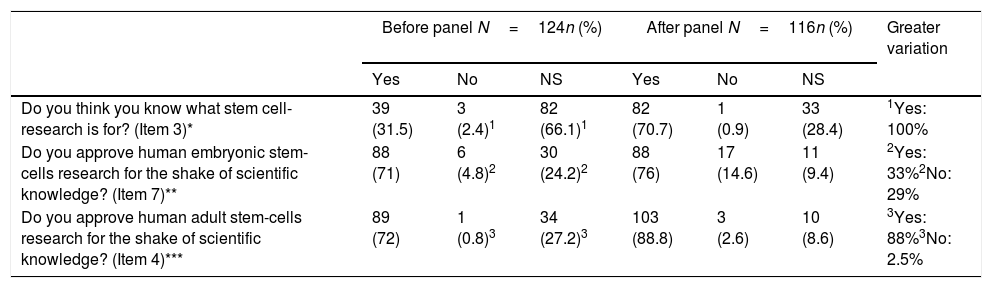

Post-panel of discussion. The number of respondents who knew about SC research and its purpose increased to 71%. This increase was statistically significant (p=0.001). The position taken by those students who in pre-panel of discussion declared themselves to be “not sure” largely contributed to this rise (p=0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.Response to items 3, 4 and 7.

Before panel N=124n (%) After panel N=116n (%) Greater variation Yes No NS Yes No NS Do you think you know what stem cell-research is for? (Item 3)* 39 (31.5) 3 (2.4)1 82 (66.1)1 82 (70.7) 1 (0.9) 33 (28.4) 1Yes: 100% Do you approve human embryonic stem-cells research for the shake of scientific knowledge? (Item 7)** 88 (71) 6 (4.8)2 30 (24.2)2 88 (76) 17 (14.6) 11 (9.4) 2Yes: 33%2No: 29% Do you approve human adult stem-cells research for the shake of scientific knowledge? (Item 4)*** 89 (72) 1 (0.8)3 34 (27.2)3 103 (88.8) 3 (2.6) 10 (8.6) 3Yes: 88%3No: 2.5% NS: not sure.

n Shows the respondents who shift opinions as a group and the direction of such a shift.

- •

Pre-panel of discussion: Most respondents approved usage of human-ASCs and human-ESCs for research (72% and 71%, respectively; Table 1). When only considering human-ASC research, 75% of the males and 72% of the females approved it. Of those 100% of medical students approved the research using human-ASCs while 33% of students enrolled in occupational therapy were against it (data not shown in the tables). These were the largest difference of opinion among students as classified by university fields of study. This difference is statistically significant (p=0.004). Regarding human-ESC research, a statistically significant difference was found among genders as well as university field of study. While 3% of females disapprove of its use 19% of males did not approve (p=0.02). The rate of disapproval for the research on human-ESCs was higher among students enrolled in Medicine and Occupational Therapy degrees (23% and 33%, respectively; p=0.035).

- •

Post-panel of discussion: The rate of approval for the usage of human ESC and human ASC studies increased. This rise was statistically significant concerning human-ASC research (from 72% to 88%; p=0.001) and ESCs (from 71% to 76%, p=0.001). This change was due to a new position taken by those who initially disapprove (Table 1). The differences seen before amongst respondents of different sex and university field of study were negligible (data not shown).

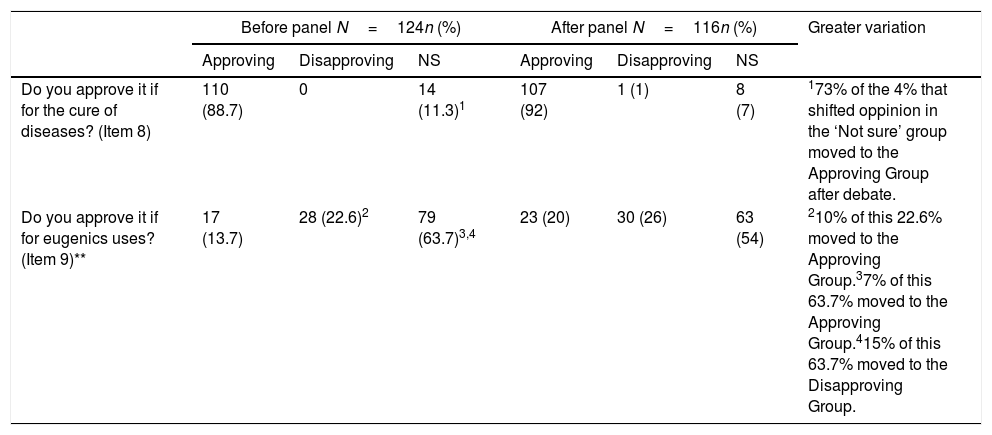

• Pre-panel of discussion: First we shall refer to opinions concerning the application of human-ESC investigation to treat disease (Table 2). This issue was a key point of discussion at the panel of discussion. All together, most respondents approved this use before attending to the panel of discussion (89%). When the responses were examined by university field of studies 11% of the Optics and optometry students and 22% of the medical students said to be “Not sure” (p=0.012 when compared to opinion of the remaining students). Respondents who approved of the use of human-ESC research for therapeutics rose to 92% after panel of discussion (Table 2). The opinion-shift corresponded to the undecided respondents found in the pre-panel of discussion. No statistically significant difference was encountered in relation to the university field of studies.

Response to items 8 and 9 Do you approve human embryonic stem-cells research if for the cure of diseases?

| Before panel N=124n (%) | After panel N=116n (%) | Greater variation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approving | Disapproving | NS | Approving | Disapproving | NS | ||

| Do you approve it if for the cure of diseases? (Item 8) | 110 (88.7) | 0 | 14 (11.3)1 | 107 (92) | 1 (1) | 8 (7) | 173% of the 4% that shifted oppinion in the ‘Not sure’ group moved to the Approving Group after debate. |

| Do you approve it if for eugenics uses? (Item 9)** | 17 (13.7) | 28 (22.6)2 | 79 (63.7)3,4 | 23 (20) | 30 (26) | 63 (54) | 210% of this 22.6% moved to the Approving Group.37% of this 63.7% moved to the Approving Group.415% of this 63.7% moved to the Disapproving Group. |

NS: not sure.

• Post-panel of discussion: After the panel of discussion 6% of males were against the use of human-ESCs for medical treatment, while no female it was opposed, this difference was statistically significant (p=0.049).

Health-sciences student's opinion about eugenic applications resulting from research with human SC• Pre-panel of discussion: As seen in Table 2, of the 64% of students responding “Not sure” before the panel of discussion 54% maintained their response after. Percentage of approvers significantly shifted from 14 to 20% after exposure to the panel of discussion (p=0.027), although no significant change was found between genders. There was no statistically significant difference concerning gender and university field of study either before or after the panel of discussion. Amongst the approvers of eugenic applications of human SCs, students of Optics stood out (25.5%) before the panel of discussion, whilst the disapproval was mostly seen in students of Medicine (41%).

• Post-panel of discussion: After the panel of discussion 87% and 71% gave approving and disapproving responses, respectively. All statistically significant difference disappeared and the answers reallocated uniformly amongst the different selecting options after the panel of discussion.

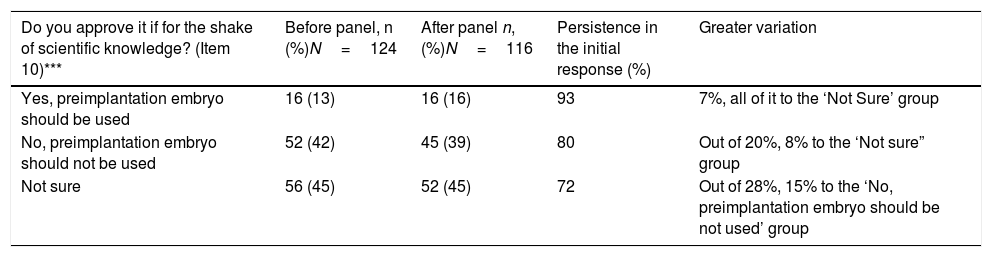

Health-sciences student's opinion about usage of human preimplantation-embryos• Pre-panel of discussion: There was a 41% disapproval rate, a 13% of approval and 45% of undecided before the panel of discussion. After the debate with the panel of discussion, disapproval response decreased to 39%, the approval response rose to 16% and the uncertainty remained unchanged (Table 3).

Regarding human preimplantation embryo (that is, human blastocysts before implantation, of less than 14 days after fertilization).

| Do you approve it if for the shake of scientific knowledge? (Item 10)*** | Before panel, n (%)N=124 | After panel n, (%)N=116 | Persistence in the initial response (%) | Greater variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, preimplantation embryo should be used | 16 (13) | 16 (16) | 93 | 7%, all of it to the ‘Not Sure’ group |

| No, preimplantation embryo should not be used | 52 (42) | 45 (39) | 80 | Out of 20%, 8% to the ‘Not sure” group |

| Not sure | 56 (45) | 52 (45) | 72 | Out of 28%, 15% to the ‘No, preimplantation embryo should be not used’ group |

• Post-panel of discussion: That 3 points increase of approval after the panel of discussion was statistically significant (p=0.000). The persistence of the original answers was 93% for those who approve and 80% for those who disapproved. Between 7% and 8% of the original categorical responses changed to the “Not sure” option. There was no statistically significant difference concerning gender and university field of study either before or after panel of discussion.

Transcendental/spiritual convictions and political biasesTranscendental/spiritual convictions classification of the respondents: With respect to the belief in the “after life”, 37% of respondents declared to be non-believers, 30% said to be believers and 34% had doubts about it. Considering specific religion, 8% of respondents declared to be agnostics, 46% said they were atheists. The rest declared to belong to a specific religion. Of these declared religious, 96% said to be Catholics, 2% Protestants, 1% Orthodox and 1% Buddhists. There was no statistical difference by gender or field of study.

Relationship between respondent's transcendental/spiritual convictions bias about human-SC usage: Concerning human-ASC usage for any purpose, there was no statistical difference amongst respondents believing or not in the “after life”. A statistically significant difference (p=0.005) arose among believers and non-believers in the ‘after life’ regarding the usage of human-ESC for research. 86% of the non-believers say to approve, both before and after debating, whilst believers who accepted it were 49% before the panel of discussion and 68% after. In addition, considering the numbers of respondents that approved the usage of human-ESC for research, there was a statistically significant difference (p=0.01) amongst atheists (84%) and Catholics (54%). These percentages increased after the panel of discussion to 87% and 60%, respectively (p=0.017).

The Relation between respondent's transcendental/spiritual convictions bias about human-preimplantation-embryo use: With respect to the ethical suitability for research of human-preimplantation-embryos, the number of disapprovers was significantly higher (p=0.02) amongst believers in the “after life” (70%) than amongst the non-believers (28%) before the panel of discussion. Nonetheless, 43% of the believers in the “after life” did not have a formed opinion on this issue, whilst such an uncertainty was held by 12% of non-believers; the difference being also statistically significant (p=0.015). That human preimplantation-embryos should be barred from any usage was a majority, though not overwhelming opinion among Catholics (56%) before the panel of discussion. In this, atheists holding such a restrictive opinion were minority (21%) before the panel of discussion. These differences are significant (p=0. 003). After the panel of discussion, all of these results barely changed, maintaining the statistical significance. Here the atheists declared to have doubts (55% before panel, 53% after Panel).

Political classification of the respondents: Regarding political proclivity, 40% of respondents declared to be progressive, or “left-wing”, whilst 30% stated to be conservative, or “right-wing” the rest did not declare a political tendency. There was no statistically significant difference amongst their genders or field of study.

Relationship between respondent's political bias about the use of human-SC: The approval for the use of human-ASC, was higher amongst those having progressive tendency (83%) when compared to the conservative respondents (71%). These tendencies were recorded before the panel of discussion. These tendencies switched after the panel of discussion. Approving conservatives were higher than the approving progressives (90% versus 87%, respectively). Considering human-ESC usage, progressives approved at a higher percentage than right-wingers did, both before and after debating (74.5% versus 63% at pre-panel of discussion and 77% versus 68% at post-panel of discussion). However, none of these differences were statistically significant.

Relationship between respondent's political bias about human-preimplantation-embryo usage: The opinion about the usage for any circumstance of human preimplantation-embryos was divided. Forty nine percent of conservatives believed it should be banned. This opinion increased after the panel of discussion (52%). For progressives the tendency was lower (33%) and for this group the tendency decreased after the panel of discussion (27%). No statistically significant difference appeared in relation with the political convictions of respondents before or after the panel of discussion.

The influence of the panel of discussion on the respondents’ opinionRegarding human-SC usage, respondents having a strong conviction prior to the panel of discussion largely kept their initial view. Persistence of approving responses at pre- and post-panel discussion was near 94% for each, human-ESC and human-ASC studies. When the subject matter was human-ASC-research usage, many respondents that initially did not have a firm opinion, it shifted toward approval (88%). When the discussion regarded human-ESC-research usage, there was a similar shift but less in number (33%). (Table 1)

A parallel shift occurred for the opinion on human-ESC for therapeutic usage. Ninety-nine percent of respondents who initially approved it maintain their approval after the panel of discussion. Of the respondents who at first were ‘Not sure’ and then change, 73% took an approving position (Table 2). Something different happened for the opinions on human-ESC for eugenic usage. Whereas 87% of the early approvers persisted in their opinion after the panel of discussion, 10% of those who at first disapproved, changed to be in favor of its therapeutic usage. Singularly as well, only 7% of the respondents who were initially ‘Not sure’ but took a position after the panel of discussion went to approving its use; wile 15% went to the rejecting option (Table 2).

Concerning the human-preimplantation-embryo usage, 93% of the approving respondents maintained their initial position after the panel of discussion when it was 80% of the respondents that initially stated that preimplantation-embryo “should never be used” (Table 3).

DiscussionIt is often the case that polemical social aspects of science are left aside during the heath science formative years. These aspects have to be understood sooner or later.21,34 To our knowledge there are no published opinion surveys done on heath science students about the usage of human SC for research and therapies. To this date this is the first study exploring this population. Our results generally agreed with other reports done on different populations.34 It should be emphasized that before attending a panel of discussion the main source of information for the students was mass media.

In addition we do not know of any survey that reflects changes of opinion after attending a panel discussing the use of SC. Moreover we have not found any report using a panel of discussion in the education of health science students.

A panel of discussion is a formal method of interactive reasoning with potential to promote critical thinking. It is an educational tool that has been poorly utilized in the undergraduate health science education.31,35,36

Four were the objectives of this work: (1) Undergraduate students enrolled in Health-Sciences studies do agree with research on and medical use of human stem cells; (2) undergraduate students enrolled in Health-Sciences studies consider that the human preimplantation-embryo can be used for research and medical usages; (3) attitudes toward the previous two issues are linked to gender, university field of study, transcendental/spiritual convictions and political biases; (4) debating with experts modifies the stance on the issues 1–3 of above. Now we shall discuss in the following to what extent the results of the study are consistent with those assumptions.

Health-sciences students’ opinion about research on and medical use of human-SCsA large majority of respondents approved of medical research with human-ESCs and human-ASCs (range, 71–88%). The therapeutic use of human-ESCs had larger approval rate (89% before and 92% after the panel of discussion). Overall, all these results are consistent with those published by Stewart.30 Our survey also explored the opinion about the eugenic usage of human-SCs. The higher approval of their use was 20%. These results suggest that undergraduate students enrolled in Health-Sciences degrees generally agree with research and medical use of human stem cells Consequently, we think the first hypothesis of our study proved to be true.

Health-sciences students’ opinion about medical research of human preimplantation-embryosIn this issue, the surveyed students were almost evenly split between those not having a fully shaped opinion on the topic (45%, both before and after the panel of discussion) and those who disapproved of such use (42% before and 39% after the panel of discussion). Approvers did not exceed 16%. Hence, our second hypothesis was challenged. To out knowledge there are no published results regarding this issue. Considering the difference between the results obtained to test this hypothesis and those obtained for the previous hypothesis, we can only speculate whether the preimplantation-embryos did qualify as ‘more human’ than the ESCs in the students’ reasoning. This thinking, which still was held even after knowing that a good number of human preimplantation-embryos must be manipulated and ultimately destroyed to acquire human ESCs for research and therapy, would parallel the perception that seems to be deeply rooted in broad subdivisions of the general population. This evokes the reasoning of Dr. Shinya Yamanaka3 when he decided to look for a new avenue for his research after observing embryos in a later developmental stage than that of preimplantation-embryos, in which the body conformation has already appeared,

Opinions concerning the two afore-discussed hypothesis are linked to gender, university field of study, transcendental/spiritual convictions and political biasA. Gender: Before the panel of discussion more males (19%) than females (3%) disapproved the research with human-ESCs. Such a difference vanished after the panel of discussion. Yet, there were 6% of males against the therapeutic usage of human-ESCs, while no female disapproved. Regarding the eugenic usage of human-ESCs, no statistically significant difference concerning gender was found either before or after the panel of discussion. Thus, the results suggest that females can be more in favor than males regarding human-ESC usage particularly to cure diseases. This confirms the first part of our third hypothesis, i.e., that “attitudes toward research on and medical usages of human-ESCs and human preimplantation-embryos are linked to gender (…)”. Yet, we have to say that here we expected the opposite bias. That is, men would be more approving of the issues treated in the panel of discussion than women. In a previous survey conducted upon the general population of the USA, it was reported that the support to human SC research was slightly higher in males.18 Such a discrepancy between the results of the former survey in the USA and the outcome of the present study may be due either to cultural differences between Spain and the USA or to differences caused by the level of education of the cohorts examined. Further studies should be done on this issue

B. University field of study: Results showed that statistically significant differences were found regarding opinions about human-ESC-usage when considering the field of study. It needs to be highlighted that all the medical students approved of the use of human-ASCs for research. The same students had one of the highest rates of disapproval; on the other hand, regarding human ECSs. Still, medical students were the most undecided students concerning the righteousness of human-ESCs for medical use. Again when compared to other fields of study the use of human-ESCs had a minority opinion among them. Students of Optics and Optometry stood out (25.5%) among the approvers of human-ESCs for eugenic usage, whilst the disapproval was mostly seen in medical students (41%). All of the above was before the panel of discussion. This partially confirms the second part of our third hypothesis, i.e., that “attitudes toward research and medical usages of human-SCs and human preimplantation-embryos are linked to a field of study. This relation is in a manner different to what we thought before the survey since medical students were among the more reluctant regarding the use of human ESCs and human preimplantation-embryos. After debate many medical students then had favorable responses to such uses.

C, D. Transcendental/spiritual convictions and political biases: Other possible determinants of the responses to our study were the political and spiritual proclivities of the respondents. Concerning political stands, we did not find statistically significant relationships between the self-reported political orientation and the valuations of human-ASC, human-ESC usages or the preimplantation-embryo. This is in agreement with the results reported by Stewart et al.28 and partially disproves our third hypothesis. The possible influence of transcendental or spiritual convictions was also analyzed. In our study, we have distinguished between either religious and life-transcendence beliefs or spirituality. Although religion and spirituality share common roots, they are interrelated but not the same. A spiritual belief may or may not be religious, yet religious people are spiritual.37 Previous studies have not taken this difference into account. Nevertheless, the results of our study revealed that students’ opinions connected with both notions overlap. Being or not being a believer in the ‘after life’ determines the perception about the human-preimplantation-embryo and human-ESC uses in the same way that being or not being religious does, at least for the Catholic students participating in our study. According to our results, those respondents who declared not to believe in the ‘after life’ as well as those stating to be atheists were significantly more supportive of the use of human-preimplantation-embryos and human-ESCs for research and therapeutic purposes. This agrees with another study that explored religious belief exclusively.26,29 Similarly, the believers in the ‘after life’ were mostly supporters of barring human preimplantation-embryos for research and application purposes. Such a difference was even more obvious among the respondents who declare to be Catholics, which is in full accordance with a previous study.19,29 This proved the last part of our third hypothesis to be true.

Overall, the results of the present study confirmed our third hypothesis. That is, it was shown that attitudes toward research and medical applications of human SCs and human preimplantation-embryos were related to the gender of respondents to a lesser extent. The respondent's field of study and spiritual conviction were more important. And we found no difference when their political sympathy was taken into account. The latter finding was certainly a surprise to us.

All of these findings were related to the respondents’ opinions before the panel of discussion.

Panel discussion modifies the stance on the issues 1–3 of aboveIt has been remarked that support for human SC research, which includes ESC and preimplantation-embryo, increases considerably with the personal level of education, ethical traits, perceived usefulness and the frame of any possible panel of discussion on the topic.18,28,30 The population surveyed in the present study was undergraduate students enrolled at several Health-Sciences degrees. The panel of discussion (of the Lincoln-Douglas type) was held within a scientific framework. The experts participating on the topic could personally have spiritual/non-spiritual and political variables considered in the survey. Our results show that, before the panel of discussion, the main source of respondents’ information on the surveyed topics was the mass media. This agrees with a study carried out in the general population.20 The panel of discussion was useful for clarifying respondents approving or disapproving opinion on the explored items.19 Significantly, the debate with the panel of discussion had an influence on those respondents who did not have a formed opinion on the subjects (p<0.001). For instance, students that did not have a formed opinion about the ethical appropriateness of the usage of human preimplantation-embryos for research and clinical purposes were the majority before the panel of discussion. After the panel of discussion, students’ opinion on this subject shifted significantly toward backing opinions (3%). The same was true with students that had negative opinions on that subject. Therefore, we assume our fourth hypothesis proved to be correct. This is true despite if a certain confusion about the origin of human ESCs and human preimplantation-embryos remained apparent. This supports that both panel of discussion and debates are methods to stimulate critical thinking.36,38 The panel of discussion is a useful training tool. In our experience, teachers play a fundamental role in fostering incisive and reflexive participation of students in debating. Practice in these discussions also accelerates the learning of how to ask good questions. Panels of discussion in university and academic settings are good opportunities for implementing such a practice. Nevertheless, it shall be necessary to consider the nature and extent of students’ specific knowledge prior to asking them to engage in a particular argument.39

ConclusionThe results of this study show that heal science undergraduate students generally agree with the usage of human SC for research and therapies, but less so for their eugenetic usage. The students are also in favor of the usage of pre-implantation embryos for medical research. These attitudes are a reflection on the degree and transcendental convictions, but not as much on their gender. The limited number of respondents prevent us to determine some aspect in relation to sex or spiritual convictions. The student's political believes were no significance. Conversely we found that undergraduate health science students improved their level of understanding after attending to a panel of discussion on these controversial topics. In our study, the surveyed students significantly changed their opinion on the usage of human SC for research and therapeutic ends. Concomitant, our results also show the most of the differences related to gender, field of study, political and spiritual feelings disappeared after the panel of discussion. Our main conclusion is that within an appropriated scientific frame a panel of discussion with experts of different ethical and political believes will help health science undergraduate students to understand better scientific and ethical issues. This is true even for students that were educated in scientific and ethical issues. Panels of discussion can be implemented in the undergraduate health science university teaching. This will aid to expose students to real world ethical and scientific controversies.36

Conflict of interestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

The authors thank all the students who gave up their time to participate in the study and Ms. Ana-M. Álvarez-Castrosín for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.