The 2013 reform of the nursing education system in Morocco, which introduced the License-Master-Doctorate framework and the establishment of Higher Institutes of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques (ISPITS), aimed to modernize higher education and enhance nursing practices. This study examines gender differences in learning strategies among nursing students, considering Morocco's cultural specificities.

Subjects and methodsAn exploratory study was conducted with 625 first-year students enrolled in three ISPITS in the Marrakech-Safi region during the first semester of the 2022–2023 academic year. Data were collected using the “Mes Outils de Travail Intellectuel” questionnaire, adapted to the Moroccan context. Statistical analyses employed non-parametric tests, including the Mann–Whitney U test for gender comparisons, and a generalized linear model to control for confounding variables such as the institution of origin and field of study.

ResultsThe findings indicate an overall homogeneity between genders in the use of cognitive, metacognitive, and affective tools, with a statistically significant but weak difference in the “Structuring-Reorganization” dimension (p = 0.044, small effect size).

ConclusionThe study highlights a general equity in learning strategies, challenging gender stereotypes. However, the overrepresentation of women (78.2%) in the sample limits the analysis of male behaviors. These findings emphasize the need for inclusive pedagogies tailored to local specificities and mixed-method approaches to further explore sociocultural and educational dynamics.

La reforma de 2013 del sistema de formación en ciencias de enfermería en Marruecos, que introdujo el marco de Licenciatura-Máster-Doctorado y la creación de los Institutos Superiores de Profesiones de Enfermería y Técnicas de Salud (ISPITS), tuvo como objetivo modernizar la educación superior y mejorar las prácticas de enfermería. Este estudio analiza las diferencias de género en las estrategias de aprendizaje de los estudiantes de enfermería, considerando las especificidades culturales de Marruecos.

Sujetos y métodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio exploratorio con 625 estudiantes de primer año inscritos en tres ISPITS de la región de Marrakech-Safi durante el primer semestre del año académico 2022–2023. Los datos se recopilaron utilizando el cuestionario «Mes Outils de Travail Intellectuel», adaptado al contexto marroquí. Los análisis estadísticos emplearon pruebas no paramétricas, incluido el test U de Mann–Whitney para comparar los géneros, y un modelo lineal generalizado para controlar las variables de confusión, como el instituto de origen y la especialidad.

ResultadosLos resultados revelan una homogeneidad general entre los géneros en el uso de herramientas cognitivas, metacognitivas y afectivas, con una diferencia estadísticamente significativa pero débil en la dimensión «Estructuración-Reorganización» (p = 0,044, tamaño del efecto pequeño).

ConclusiónEl estudio destaca una equidad general en las estrategias de aprendizaje, cuestionando los estereotipos de género. Sin embargo, la sobrerrepresentación de mujeres (78,2%) en la muestra limita el análisis de los comportamientos masculinos. Estos resultados subrayan la necesidad de pedagogías inclusivas adaptadas a las especificidades locales y de enfoques mixtos para profundizar en la exploración de las dinámicas socioculturales y educativas.

The 2013 reform of Morocco's nursing and health sciences education system marked a pivotal step in modernizing higher education in this field. The establishment of the Higher Institutes of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques (ISPITS) and the adoption of the Bachelor-Master-Doctorate (BMD) system were intended to meet the growing demands of an evolving healthcare system. These reforms introduced new requirements for professional competencies and learning autonomy, aiming to enhance the quality of care and the effectiveness of nursing practices.1–5 However, challenges in implementing these changes highlight the importance of pedagogical support as a crucial lever to foster deep learning strategies, including critical reflection and sustainable knowledge acquisition.6,7

In this context, gender disparities in learning strategies and academic performance have emerged as a significant concern. International research indicates that women often employ rigorous learning strategies, particularly metacognitive approaches and effective resource management, which provide them with an academic advantage in various educational settings.8–11 These disparities, however, are shaped by sociocultural norms, institutional expectations, and gendered representations of professional roles.12,13 Conversely, other studies highlight that these differences can be mitigated in environments that explicitly promote equal opportunities and pedagogical inclusivity.14,15

In Morocco, sociocultural specificities, particularly the societal perceptions of the nursing profession, are likely to uniquely influence students' learning strategies. Yet, limited research has addressed these dynamics, especially within nursing education. Examining cognitive, metacognitive, and affective strategies is particularly relevant in this context, as these dimensions encompass critical processes of reflection, knowledge management, and affective motivation essential for academic success.16,17

This study seeks to explore gender differences in learning strategies among students in Moroccan ISPITS institutions, while identifying barriers and facilitators specific to their success. By considering local specificities and pedagogical challenges, this research aims to propose tailored educational recommendations that promote equity in Moroccan educational practices. The findings may also serve as a model for other developing countries facing similar challenges in modernizing their health education systems.

Subjects and methodsStudy location and target populationThis exploratory study was conducted across three ISPITS institutions in the Marrakech-Safi region, located in central-western Morocco, one of the country's 12 administrative regions.18 The study took place during the first semester of the 2022–2023 academic year. The target population consisted of 625 first-year students enrolled in the bachelor's program. An exhaustive sampling method was employed, including all eligible students from the three institutions. A high response rate of 92% was achieved, reflecting strong student participation. Furthermore, no missing data were observed in the collected responses, which enhances the robustness of the analyses performed.

Data collection instrumentThe instrument used in this study was the self-administered questionnaire “Mes Outils de Travail Intellectuel” (MOTI), developed by Wolfs (1998) to analyze learners' perceptions of their learning practices. This tool is particularly well-suited for this research, as it was specifically designed to evaluate learning strategies, attitudes, and behaviors, especially among students beginning higher education.19

The adapted version of the questionnaire includes 34 questions and 56 items, structured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always.” The items are categorized into three main domains: cognitive tools, metacognitive tools, and affective and support tools.

To ensure its cultural and educational relevance, the questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of Moroccan experts, including a nursing education specialist. This review facilitated the adjustment of ambiguous items while preserving the original language (French), which is commonly used in Moroccan higher education. A pilot test involving 30 first-year nursing students from an institution outside the study region was conducted to enhance the clarity and contextual appropriateness of the questionnaire.

The psychometric robustness of the instrument was confirmed through rigorous analyses. Internal consistency, measured using Cronbach's alpha, demonstrated high reliability, and exploratory factor analysis validated the tool's factorial structure. Consequently, the instrument is reliable, scientifically rigorous, and well-suited to the specificities of the Moroccan context.20

MethodologyData collectionData collection was conducted anonymously in compliance with ethical standards. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 25.0), following a rigorous methodology tailored to the nature of the data.

Descriptive analysisA univariate analysis was utilized to describe and summarize the participants' characteristics. Continuous variables were reported using mean and standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies.21 Associations between qualitative variables were examined using the chi-square test. For cells with expected counts below five, Fisher's exact test was employed to ensure statistical validity.22

Bivariate analysisTo investigate gender differences in the use of intellectual tools, the normality of the data was tested using Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Results confirmed significant deviations from normality (p < 0.001). Consequently, parametric tests, such as Student's t-test, were deemed inappropriate.23 Gender comparisons were conducted using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test, a robust alternative to the t-test for independent samples.24 Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's guidelines to quantify the magnitude of observed differences.25

Multivariate analysisTo account for confounding variables, a generalized linear model (GLM) was applied to assess the effect of gender on the use of intellectual tools. The GLM was selected for its capacity to model relationships between continuous dependent variables and independent variables that may be qualitative, quantitative, or mixed.26 This approach is particularly suitable in contexts requiring covariate adjustments to evaluate the direct effect of a specific independent variable (here, gender), while controlling for factors such as the origin of the ISPITS and the academic track.

Model fit criteria, including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), were computed to assess the overall quality of the model. These indicators facilitated comparisons among models and identified the optimal balance between complexity and predictive accuracy. Additionally, confidence intervals for the coefficients were analyzed to ensure the robustness and precision of statistical conclusions.27 This rigorous methodology provides a reliable and valid interpretation of the relationships among the studied variables.

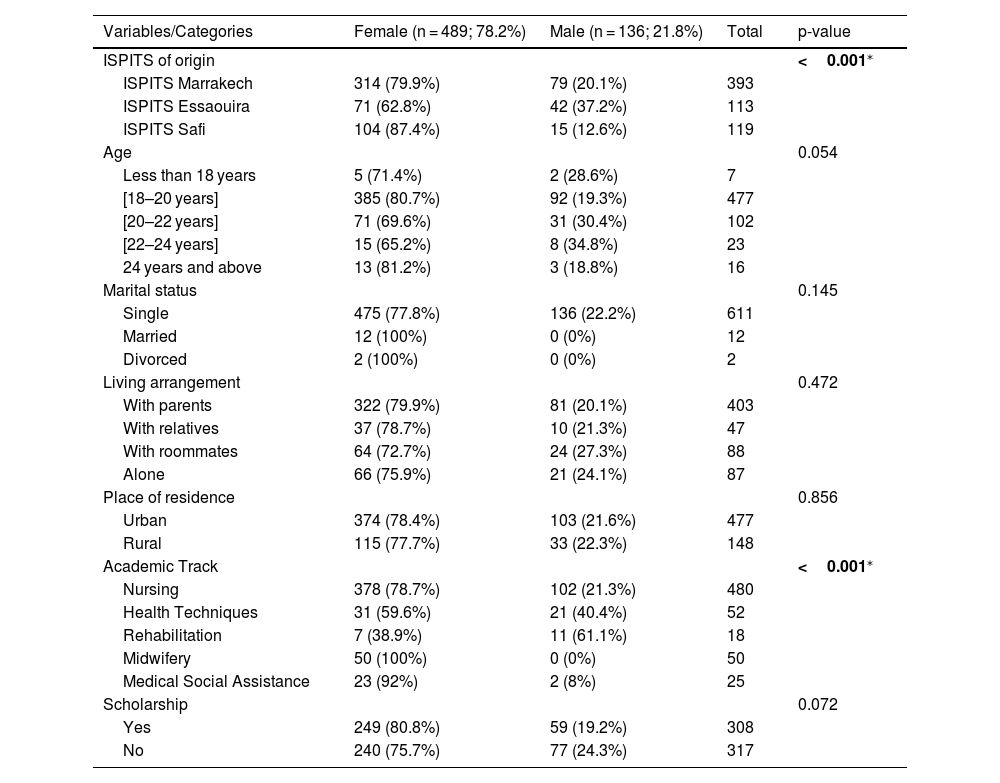

ResultsDescriptive analysisParticipant profile by genderThe study included a total of 625 students, comprising 489 women (78.2%) and 136 men (21.8%). An analysis of the data by ISPITS origin revealed significant gender differences (p < 0.001). At the Marrakech ISPITS headquarters, 79.9% of participants were women compared to 20.1% men, representing a less pronounced imbalance compared to the Safi annex (87.4% women) and Essaouira annex (62.8% women). These findings highlight an overall overrepresentation of women, particularly pronounced in Safi.

Regarding age, the majority of participants (76.3%) fell within the [18–20 years] age group, with a high proportion of women (80.7%). In older age groups, there was a slight increase in the proportion of men, although gender differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.054).

Variables related to marital status, type of cohabitation, and place of residence showed no significant gender disparities. The majority of students were single (97.8%), lived with their parents (79.9%), and resided in urban areas (78.4% women, 21.6% men).

Conversely, significant differences were observed in program choice (p < 0.001). Women predominated in nursing (78.7%) and midwifery (100%), whereas men were more represented in rehabilitation and physiotherapy programs (61.1%). Finally, no significant gender differences were found regarding scholarship eligibility (p = 0.072) (Table 1).

Socio-economic, bio-demographic, and educational characteristics of participants by gender.

| Variables/Categories | Female (n = 489; 78.2%) | Male (n = 136; 21.8%) | Total | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISPITS of origin | <0.001⁎ | |||

| ISPITS Marrakech | 314 (79.9%) | 79 (20.1%) | 393 | |

| ISPITS Essaouira | 71 (62.8%) | 42 (37.2%) | 113 | |

| ISPITS Safi | 104 (87.4%) | 15 (12.6%) | 119 | |

| Age | 0.054 | |||

| Less than 18 years | 5 (71.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | 7 | |

| [18–20 years] | 385 (80.7%) | 92 (19.3%) | 477 | |

| [20–22 years] | 71 (69.6%) | 31 (30.4%) | 102 | |

| [22–24 years] | 15 (65.2%) | 8 (34.8%) | 23 | |

| 24 years and above | 13 (81.2%) | 3 (18.8%) | 16 | |

| Marital status | 0.145 | |||

| Single | 475 (77.8%) | 136 (22.2%) | 611 | |

| Married | 12 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 12 | |

| Divorced | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 2 | |

| Living arrangement | 0.472 | |||

| With parents | 322 (79.9%) | 81 (20.1%) | 403 | |

| With relatives | 37 (78.7%) | 10 (21.3%) | 47 | |

| With roommates | 64 (72.7%) | 24 (27.3%) | 88 | |

| Alone | 66 (75.9%) | 21 (24.1%) | 87 | |

| Place of residence | 0.856 | |||

| Urban | 374 (78.4%) | 103 (21.6%) | 477 | |

| Rural | 115 (77.7%) | 33 (22.3%) | 148 | |

| Academic Track | <0.001⁎ | |||

| Nursing | 378 (78.7%) | 102 (21.3%) | 480 | |

| Health Techniques | 31 (59.6%) | 21 (40.4%) | 52 | |

| Rehabilitation | 7 (38.9%) | 11 (61.1%) | 18 | |

| Midwifery | 50 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 50 | |

| Medical Social Assistance | 23 (92%) | 2 (8%) | 25 | |

| Scholarship | 0.072 | |||

| Yes | 249 (80.8%) | 59 (19.2%) | 308 | |

| No | 240 (75.7%) | 77 (24.3%) | 317 | |

P-values were calculated using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for small cell counts.

The results presented in Fig. 1 reveal an overall homogeneity in the use of cognitive, metacognitive, and affective tools between genders. The mean scores for each tool were used to generate a radar chart, providing a clear comparative representation and facilitating the visualization of general trends across genders.

This analysis highlights global equality in the use of cognitive, metacognitive, and affective tools, while identifying a few minor differences with limited practical implications. Consequently, these findings offer a clearer understanding of the participants' learning practices without necessitating specific adjustments or corrective interventions for the studied sample.

Following this general description of participants' characteristics and their use of intellectual work tools, a bivariate analysis was conducted to explore significant gender differences in the use of these tools.

Bivariate analysisNormality test of distributionsThe normality of the distributions was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. The results, presented in Table 2, indicate a significant deviation from normality for all dimensions of the intellectual tools (p < 0.001) across both genders. These findings confirm that the score distributions do not satisfy the normality assumption, thereby justifying the use of non-parametric tests for comparative analyses.

Normality tests for intellectual tools (Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk).

| Intellectual Tools | Gender | Kolmogorov-Smirnova | Shapiro–Wilk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | ddl | Sig. | Statistics | ddl | Sig. | ||

| Comprehension-Appropriation | Female | .213 | 489 | .000 | .858 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .299 | 136 | .000 | .810 | 136 | .000 | |

| Structuration-Reorganization | Female | .235 | 489 | .000 | .812 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .309 | 136 | .000 | .720 | 136 | .000 | |

| Text Analysis | Female | .216 | 489 | .000 | .832 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .237 | 136 | .000 | .827 | 136 | .000 | |

| Deep Learning | Female | .107 | 489 | .000 | .966 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .110 | 136 | .000 | .957 | 136 | .000 | |

| Mechanical Memorization | Female | .420 | 489 | .000 | .597 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .451 | 136 | .000 | .520 | 136 | .000 | |

| Surface Learning | Female | .420 | 489 | .000 | .597 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .451 | 136 | .000 | .520 | 136 | .000 | |

| Anticipation | Female | .354 | 489 | .000 | .699 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .408 | 136 | .000 | .637 | 136 | .000 | |

| Self-Assessment of Learning Difficulties | Female | .203 | 489 | .000 | .842 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .274 | 136 | .000 | .789 | 136 | .000 | |

| Planning and Time Management | Female | .379 | 489 | .000 | .750 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .394 | 136 | .000 | .707 | 136 | .000 | |

| Confidence in Abilities | Female | .305 | 489 | .000 | .824 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .334 | 136 | .000 | .784 | 136 | .000 | |

| Engagement in Studies | Female | .321 | 489 | .000 | .812 | 489 | .000 |

| Male | .413 | 136 | .000 | .685 | 136 | .000 | |

The Mann–Whitney test results (Table 3) indicate a significant difference in the Structuration-Reorganization dimension (p = 0.044), although with a small effect size (r = 0.08). No significant differences were observed for the other intellectual tools, suggesting overall homogeneity in learning strategies between genders.

Comparative analysis of intellectual tools by gender (Mann–Whitney test).

| Intellectual Tools | Score | Gender | p-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 489) | Male (n = 136) | |||||||||

| Mean | Median | Variance | SD | Mean | Median | Variance | SD | |||

| Cognitive Tools | ||||||||||

| Comprehension-Appropriation | 7 | 3.83 | 3 | 6.42 | 2.53 | 4.18 | 6 | 6.96 | 2.64 | 0.274 |

| Structuration-Reorganization | 5 | 3.53 | 4 | 2.62 | 1.62 | 3.67 | 5 | 3.19 | 1.79 | 0.044⁎ |

| Text Analysis | 3 | 1.39 | 1.5 | 1.43 | 1.20 | 1.28 | 1 | 1.41 | 1.19 | 0.472 |

| Deep Learning | 15 | 8.75 | 8 | 11.03 | 3.32 | 9.12 | 9 | 12.97 | 3.60 | 0.270 |

| Mechanical Memorization | 3 | 0.60 | 0 | 1.11 | 1. 05 | 0.38 | 0 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.066 |

| Surface Learning | 3 | 0.60 | 0 | 1.11 | 1. 05 | 0.38 | 0 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.066 |

| Metacognitive Tools | ||||||||||

| Anticipation | 3 | 2.17 | 3 | 1.31 | 1.14 | 2.25 | 3 | 1.37 | 1.17 | 0.228 |

| Self-Evaluation of Learning Difficulties | 5 | 2.53 | 2 | 3.70 | 1.92 | 2.70 | 2 | 4.20 | 2.05 | 0.394 |

| Affective and Support Tools | ||||||||||

| Work Planning/Time Management | 5 | 2.83 | 3 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 2.88 | 3 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.630 |

| Confidence in Abilities | 3 | 1.84 | 2 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 1.74 | 2 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.094 |

| Engagement/Commitment to Studies | 4 | 2.28 | 2 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 2.31 | 2 | 0.35 | 0.59 | 0.860 |

SD: Standard deviation.

The Mann–Whitney test explored raw gender differences, while the generalized linear model was used to assess the gender effect while controlling for confounding variables.

Multivariate analysis: Generalized Linear Model (GLM)The simplified GLM (Table 4), adjusted for the ISPITS of origin and academic tracks, reveals a significant constant for the use of the Structuring-Reorganizing tool (B = 1.060, p = 0.005). Gender (male vs. female) does not exhibit a significant effect (B = 0.225, p = 0.563), and no notable influence is detected for ISPITS institutions (e.g., ISPITS Marrakech: B = 0.119, p = 0.415) or academic tracks (e.g., Nursing: B = 0.133, p = 0.468).

Summary of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) results.

| Variable | Coefficient (B) | Standard Error | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | Wald Value | p-valeur | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.060 | 0.378 | 0.324 | 1.795 | 7. 979 | 0.005** | 2337.166 | 2403.044 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 0.225 | 0.389 | −0.538 | 0.988 | 0.334 | 0.563 | ||

| ISPITS of Origin | ||||||||

| ISPITS Marrakech | 0.119 | 0.144 | −0.167 | 0.405 | 0.663 | 0.415 | ||

| ISPITS Essaouira | 0.080 | 0.158 | −0.598 | 1.056 | 0.295 | 0.612 | ||

| Academic Track | ||||||||

| Nursing | 0.133 | 0.183 | −0.226 | 0.493 | 0.527 | 0.468 | ||

| Midwifery | 0.015 | 0.158 | −0.254 | 0.283 | 0.010 | 0.915 | ||

Model fit criteria (AIC = 2337.166; BIC = 2403.044) indicate acceptable model fit. Confidence intervals for the coefficients include zero, confirming the absence of significant effects for the studied variables on the use of the Structuring-Reorganizing tool.

The results reveal a general homogeneity between men and women in the use of intellectual tools, with no notable influence of the studied factors, confirming an overall equity in educational practices within ISPITS-M.

DiscussionLearning strategies are deeply influenced by entrenched cultural, social, and institutional factors, particularly gender identities and roles, which are often reinforced by educational systems.12 These divergences emerge early in life, shaped by socialization processes, parental interactions, and psychobiological influences.13 Traditionally, men have been perceived as prioritizing careers and social lives, while women place greater emphasis on academic success, adjusting their efforts accordingly to excel in their studies.28

However, the findings of this study, conducted within the Moroccan ISPITS educational context, reveal an overall gender parity in the use of cognitive, metacognitive, and affective tools. One notable exception pertains to the “Structuration-Reorganization” dimension, where a significant yet weak difference (p = 0.044, small effect size) was observed. This strategy, essential for deep learning, is linked to higher academic performance and better organizational skills.7,29 These results align with the findings of Wolfs (2007), suggesting that structured educational environments, such as those provided by ISPITS, play a significant role in mitigating gender disparities frequently reported in other educational contexts.9

The overrepresentation of women (78.2%) in the sample reflects sociocultural norms that associate caregiving professions with feminine roles.28 While consistent with global trends reported in international studies,9 this imbalance limits the statistical power to detect subtle differences among men.22,30 These results underscore the need for future research incorporating more balanced samples and exploring additional contextual variables, such as familial support and institutional expectations.31

Moreover, our findings challenge generalizations that women more frequently adopt deep learning strategies and exhibit intrinsic academic motivation.13 The observed parity in learning practices, corroborated by Hasanzadeh & Shahmohamadi (2011), may be attributed to the inclusive nature of the educational environments studied, which appear to mitigate gender stereotypes and promote equal opportunities.32 Furthermore, no significant gender differences in academic confidence were identified, contradicting stereotypes that women possess lower self-esteem regarding their academic abilities.33 These findings suggest that ISPITS pedagogical environments foster egalitarian approaches, minimizing gender biases.

Nonetheless, the predominance of surface memorization strategies among all participants highlights deficiencies in current pedagogical practices. Such strategies, often ineffective for the durable transfer of knowledge to practical contexts, underline the urgent need for pedagogies that promote deep learning.19,34 Interactive and collaborative approaches encouraging critical thinking and active engagement emerge as promising avenues for enhancing learning quality, particularly in nursing education, where the application of knowledge to real-world scenarios is paramount.2,29,35

While the absence of significant gender disparities does not warrant differentiated interventions, it emphasizes the importance of inclusive pedagogical approaches aimed at maximizing all students' potential, regardless of gender.7 Additionally, strategic policies to increase male representation in nursing could rebalance gender roles within the profession, enrich group dynamics, and improve representation in the healthcare sector.36

In conclusion, this study challenges gendered stereotypes associated with learning strategies, highlighting overall gender parity. It underscores the importance of inclusive pedagogies tailored to local sociocultural contexts to enhance equity and effectiveness in educational environments. The findings demonstrate the role of Moroccan ISPITS in reducing gender disparities and fostering deep learning strategies. However, the overrepresentation of women (78.2%) in the sample limits the generalization of conclusions to male students' behaviors.

Future research should include more balanced samples, investigate the evolution of learning strategies across academic trajectories, and integrate qualitative approaches to deepen sociocultural analysis. These findings also call for targeted educational reforms to diversify professional profiles in health professions and promote equity and academic excellence in Morocco.

FundingThe author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this Article.

Ethical considerationsThis research was conducted in accordance with local ethical principles, with explicit written authorization obtained from the ISPITS management. Informed consent was obtained from all students who voluntarily participated in the study. They were provided with clear explanations of the study's objectives and procedures and informed of their right to withdraw at any time without justification. Confidentiality and data security were strictly maintained, and fundamental ethical principles–including Autonomy, Beneficence, Non-maleficence, and Justice–were meticulously upheld throughout the research process.

The authors affirm that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors express their sincere gratitude to José-Luis Wolfs, Professor of Educational Sciences at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, for his collaboration and for granting permission to use his measurement instrument, “Mes Outils de Travail Intellectuels.”