The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) is an assessment format developed by Harden to evaluate the clinical competencies of medical students. Our university has been using this assessment in dentistry for the past 8 years, incorporating Standarized patients (SPs) into its stations. Proper training of SPs is essential to ensure objectivity. To date, no study has determined the validity of the student evaluations provided by SPs. The aim of this study was to assess the level of agreement between professors and SPs when evaluating the periodontics station of the OSCE during the 2022/2023 academic year in dental students.

Material and methodsThe SPs evaluated the students' responses after completing the periodontics station using an 18-question rubric. Meanwhile, the assigned professors from a hidden control room assessed the students using the same checklist. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and significance tests. Quantitative variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Interobserver agreement for categorical variables with Cohen's kappa coefficient. A significance level of 0.05 was adopted.

ResultsA total of 210 students were evaluated. The correlation between the assessments of the SPs and professors was poor for most of the items, with good correlation for diagnosis; statement relating the condition to stress and anxiety; and informed consent.

ConclusionsSP evaluations of dental students’ OSCEs do not correlate well with those of their professors despite efforts to educate these SPs.

El Examen Clínico Objetivo Estructurado (ECOE) es un formato desarrollado por Harden para evaluar competencias clínicas en estudiantes de medicina. Nuestra universidad lo utiliza en odontología desde hace 8 años, incorporando pacientes estandarizados (PEs) en sus estaciones. La adecuada capacitación de los PEs es esencial para garantizar la objetividad de la prueba. Hasta la fecha, no se ha estudiado la validez de las evaluaciones realizadas por los PEs. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar la concordancia entre profesores y PEs en la estación de periodoncia del ECOE durante el curso 2022/2023 en estudiantes de Odontología.

Material y métodosLos PEs evaluaron las respuestas de los estudiantes utilizando una rúbrica de 18 preguntas, mientras que los profesores, desde una sala de control oculta, realizaron la misma evaluación. Se aplicaron estadísticas descriptivas y pruebas de significancia. La normalidad de las variables cuantitativas se evaluó con la prueba de Shapiro–Wilk, y el acuerdo inter-observador mediante el coeficiente kappa de Cohen, con un nivel de significancia de 0,05.

ResultadosSe evaluaron 210 estudiantes. La correlación entre las evaluaciones de PEs y profesores fue baja en la mayoría de los ítems, con buena concordancia sólo en diagnóstico, relación de la patología con estrés y ansiedad, y consentimiento informado.

ConclusionesLas evaluaciones de los PEs no se correlacionaron adecuadamente con las de los profesores, a pesar de los esfuerzos de capacitación.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the level of agreement between the assessments made by professors and standardized patients (SPs) in the periodontics station of the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) administered to dental students.

The OSCE was introduced by Dr. Ronald M. Harden in the 1970s.1 It is a practical examination that assesses students' clinical skills, knowledge, and attitudes in various situations in a structured and planned manner. The OSCE emphasizes “doing” rather than just “knowing,” shifting the focus from traditional forms of assessment. Its purpose is not merely to measure knowledge acquisition but to evaluate students' ability to synthesize information and apply clinical knowledge, thus enabling examiners to assess their diagnostic expertise and clinical decision-making.2 This assessment methodology has been used in the medical field for over 40 years and has since been adopted by other health disciplines, including dentistry. In 2017, our University began utilizing this assessment format, which is now considered the Gold Standard for assessing clinical skills.3

The OSCE consists of a series of stations or scenarios where students or professionals are evaluated. These assessments typically occur in an interactive environment involving SPs who recreate real clinical situations.1,4 Students navigate through these stations, completing the required tasks. To conduct an effective OSCE, clear objectives and defined skills to be measured at each station must be established. Stations can vary in duration, ranging from 4 to 10 min, and typically, one or two assessors monitor each station to observe and evaluate students' performance in specific areas. Standardized checklists with predetermined criteria and grading rubrics—comprising 10 to 30 items with calibrated scores—are used for assessment.3,5 Regular quality checks and ongoing improvements are essential to maintaining the psychometric accuracy of the test.6

In OSCEs with SPs, the role of these actors becomes especially crucial. They are given scripts designed to simulate comprehensive medical histories, including diseases and medications. These scripts are collaboratively developed by the station designers to assess a range of competencies beyond theoretical knowledge in dentistry. They also help evaluate students' abilities to manage and respond to challenging or stressful patient interactions, offering a more holistic assessment of competencies acquired beyond the study program.3

Typically, OSCEs are evaluated by a team of professional markers appointed by the assessment body. These assessors are trained and follow established criteria to ensure objectivity and consistency in evaluating candidates' competencies.5 Generally, assessments are not conducted by the SPs themselves, but by trained assessors.7 However, at our University, SPs assess the stations in which they participate using a checklist developed by the station designers. This checklist aims for standardization, ensuring the validity of the test and minimizing subjective evaluations by the SPs.8

The justification for this project stems from the gap in research regarding whether the outcomes of an OSCE evaluated by SPs are comparable to those conducted by course instructors.

Material and methodsThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our University on July 8, 2022, and assigned the internal code CIPI 22.238. The OSCE system was used to assess students during the 2022–2023 academic year. These students were in their fifth year of the Bachelor of Dentistry program and had completed basic theoretical courses along with two years of clinical practice prior to the exam.9 A periodontics station was used for this study. Both SPs and examiners evaluated all participants using the same scoring rubrics.

The study followed the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation was voluntary, with no compensation or incentives. Confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed for all participants, who provided informed consent.

The OSCE consisted of five stations, with the periodontics station being the first. Before interacting with the SP, each student was provided with relevant information regarding the patient's medical and dental history, signs and symptoms, and the reason for the consultation. Once the examinees reviewed this information, they entered a room designed to replicate a dental practice, where they had eight minutes to complete the test. They encountered an SP who was required to interpret a previously studied script, simulating the presence of necrotizing gingivitis for at least five to six days.

Teachers experienced in SP training distributed and clarified the scripts and reviewed real clinical patient videos following the recruitment of 21 SPs. SPs and station examiners were recruited one week before the examination. Four of the six examiners had more than five years of teaching experience. Each examiner was assigned four SPs with the same script, organized into six groups. Additionally, the chief examiner responsible for the SP station explained the scoring rubrics to both SPs and examiners based on the rating scale, reviewed assessment videos from the previous year, and conducted simulated scoring. Concurrently, examinees participated in field training while SPs fulfilled their roles and scored alongside examiners. The passing criteria were also reiterated.

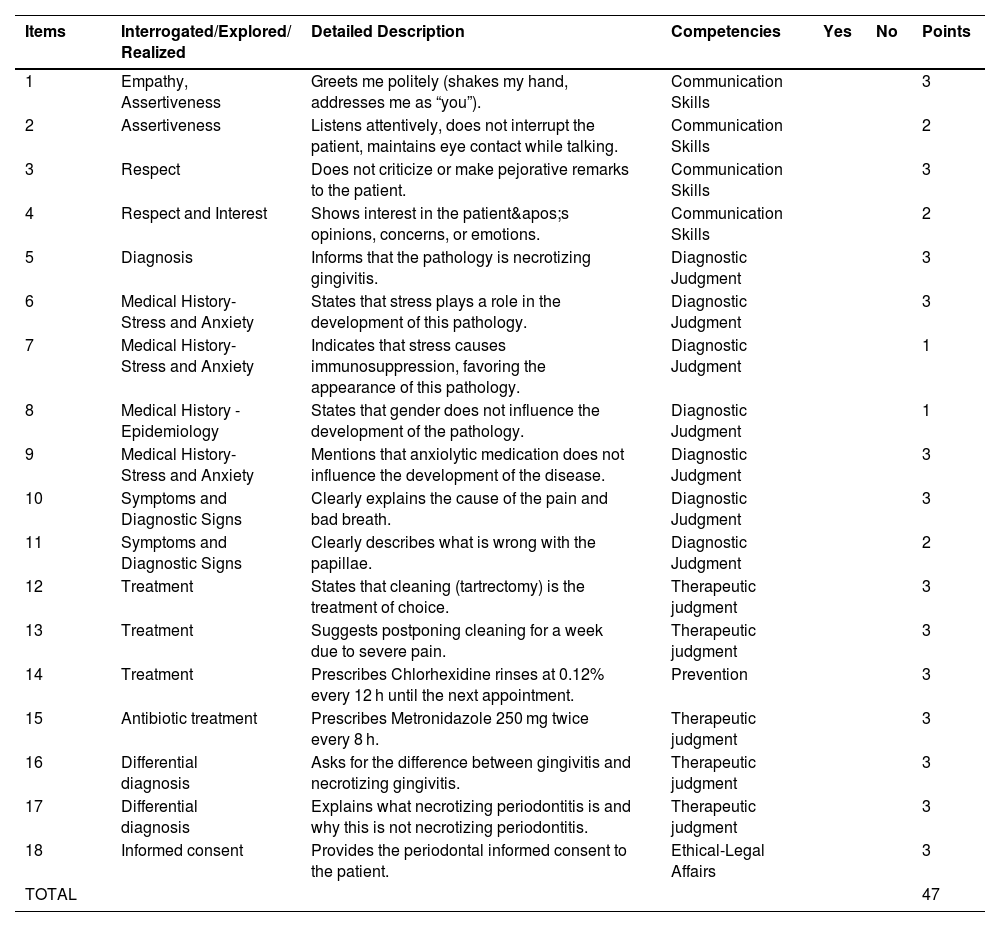

At the end of the station, SPs were responsible for evaluating the students' responses. They used a checklist containing 18 items, divided into 5 competencies: communication skills, diagnostic judgment, therapeutic judgment, prevention, and legal affairs. The checklist specified the correct answers for each section and included a YES/NO option where the examiner could note whether the student's answer was correct (“YES”) or incorrect (“NO”). Scores were assigned according to the importance of each item, with a maximum value of 3 and a minimum of 1, for a total of 47 points (Table 1).

Items included in the Periodontics Station Assessment Rubric.

| Items | Interrogated/Explored/ Realized | Detailed Description | Competencies | Yes | No | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Empathy, Assertiveness | Greets me politely (shakes my hand, addresses me as “you”). | Communication Skills | 3 | ||

| 2 | Assertiveness | Listens attentively, does not interrupt the patient, maintains eye contact while talking. | Communication Skills | 2 | ||

| 3 | Respect | Does not criticize or make pejorative remarks to the patient. | Communication Skills | 3 | ||

| 4 | Respect and Interest | Shows interest in the patient's opinions, concerns, or emotions. | Communication Skills | 2 | ||

| 5 | Diagnosis | Informs that the pathology is necrotizing gingivitis. | Diagnostic Judgment | 3 | ||

| 6 | Medical History- Stress and Anxiety | States that stress plays a role in the development of this pathology. | Diagnostic Judgment | 3 | ||

| 7 | Medical History- Stress and Anxiety | Indicates that stress causes immunosuppression, favoring the appearance of this pathology. | Diagnostic Judgment | 1 | ||

| 8 | Medical History - Epidemiology | States that gender does not influence the development of the pathology. | Diagnostic Judgment | 1 | ||

| 9 | Medical History- Stress and Anxiety | Mentions that anxiolytic medication does not influence the development of the disease. | Diagnostic Judgment | 3 | ||

| 10 | Symptoms and Diagnostic Signs | Clearly explains the cause of the pain and bad breath. | Diagnostic Judgment | 3 | ||

| 11 | Symptoms and Diagnostic Signs | Clearly describes what is wrong with the papillae. | Diagnostic Judgment | 2 | ||

| 12 | Treatment | States that cleaning (tartrectomy) is the treatment of choice. | Therapeutic judgment | 3 | ||

| 13 | Treatment | Suggests postponing cleaning for a week due to severe pain. | Therapeutic judgment | 3 | ||

| 14 | Treatment | Prescribes Chlorhexidine rinses at 0.12% every 12 h until the next appointment. | Prevention | 3 | ||

| 15 | Antibiotic treatment | Prescribes Metronidazole 250 mg twice every 8 h. | Therapeutic judgment | 3 | ||

| 16 | Differential diagnosis | Asks for the difference between gingivitis and necrotizing gingivitis. | Therapeutic judgment | 3 | ||

| 17 | Differential diagnosis | Explains what necrotizing periodontitis is and why this is not necrotizing periodontitis. | Therapeutic judgment | 3 | ||

| 18 | Informed consent | Provides the periodontal informed consent to the patient. | Ethical-Legal Affairs | 3 | ||

| TOTAL | 47 |

While the OSCE was taking place, examiners observed and listened to the test from an adjacent control room. This allowed them to assess the students' reactions and handling of the situation. Neither the SPs nor the students were aware of the hidden presence of the examiners. The examiners used the same checklist as the SPs to assess the station in parallel.

The competency “communication skills” assessed the student's attitude toward the patient, such as whether they greeted the patient courteously, listened attentively without interruption, and displayed empathy toward the SP's emotions and concerns.

The competency “diagnostic judgment” evaluated the student's ability to diagnose the ailment described by the SP. In addition to identifying the illness, the student was required to consider factors influencing the development of the illness, such as stress, immunosuppression, certain medications (e.g., anxiolytics), or the patient's gender. Finally, the student had to explain the causes of the symptoms and why the papilla had that appearance.

The competency “therapeutic judgment” consisted of five items, focusing on the specific dental treatment of the lesions, the timing of the procedure, the correct prescription of antibiotics (including dosage and duration), and distinguishing between necrotizing gingivitis, necrotizing periodontitis, and conventional gingivitis.

Two items examined “prevention” and the “ethical-legal” aspects. Students were required to recommend using a 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse twice a day for 7 days as a preventive measure for necrotizing gingivitis. Additionally, before leaving the station, they had to provide the patient with an informed consent form for the dental procedure needed to treat the diagnosed dental condition.

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and significance tests to identify differences between groups. Categorical variables were described using absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies, while quantitative variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Interobserver agreement for categorical variables was assessed using Cohen's kappa coefficient. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.3.1. A significance level of 0.05 was adopted. To ensure the internal consistency of the checklist used in the periodontics OSCE station, a reliability analysis was conducted using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The 18-item rubric yielded a Cronbach's alpha of 0.93, indicating excellent internal consistency. This high level of reliability suggests that the items included in the checklist are well-aligned and consistently measure the intended clinical competencies. These findings support the robustness of the instrument used for evaluating student performance in this station.

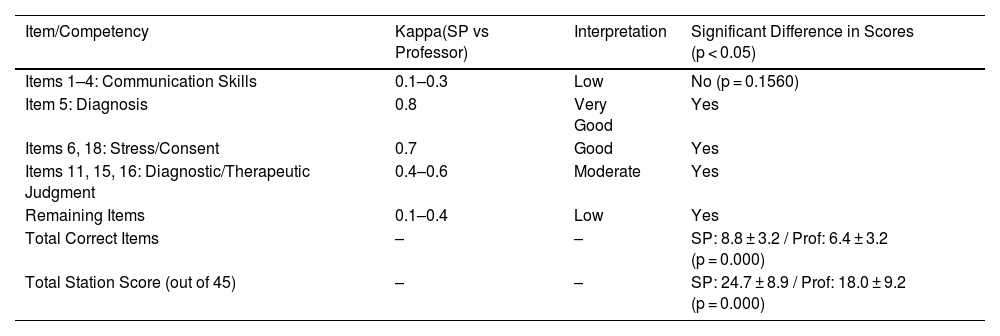

ResultsA total of 210 students were evaluated as part of this study. The inter-rater agreement between standardized patients (SPs) and professors, measured using Cohen's kappa, was generally low across most items (Table 2). Very good agreement was observed only for the diagnosis item (κ = 0.8), and good agreement for items related to medical history and informed consent (κ = 0.7). Moderate agreement was found for items assessing diagnostic and therapeutic judgment (κ = 0.4–0.6). Communication skills showed low agreement (κ = 0.1–0.3), though no significant differences were found in scores between SPs and professors for this domain (p = 0.1560). In contrast, significant differences were observed in the diagnostic/therapeutic judgment, prevention, and ethical-legal domains, with SPs consistently awarding higher scores. Overall, the total number of correct items and the final station score were significantly higher when assessed by SPs (p < 0.001).

Summary of inter-rater agreement and score differences between standardized patients and professors across OSCE assessment items and competencies.

| Item/Competency | Kappa(SP vs Professor) | Interpretation | Significant Difference in Scores (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Items 1–4: Communication Skills | 0.1–0.3 | Low | No (p = 0.1560) |

| Item 5: Diagnosis | 0.8 | Very Good | Yes |

| Items 6, 18: Stress/Consent | 0.7 | Good | Yes |

| Items 11, 15, 16: Diagnostic/Therapeutic Judgment | 0.4–0.6 | Moderate | Yes |

| Remaining Items | 0.1–0.4 | Low | Yes |

| Total Correct Items | – | – | SP: 8.8 ± 3.2 / Prof: 6.4 ± 3.2 (p = 0.000) |

| Total Station Score (out of 45) | – | – | SP: 24.7 ± 8.9 / Prof: 18.0 ± 9.2 (p = 0.000) |

When segmenting the results according to the competencies assessed, we find the following results:

Communication Skills: The number of correct items is not significantly different when assessed by the teacher compared to the actress (2.57 ± 0.69 vs. 2.64 ± 0.64; p = 0.1560).

Diagnostic/Therapeutic Judgment: The number of correct items related to diagnostic/therapeutic judgment is significantly lower when assessed by the teacher compared to the actress (5.44 ± 2.54 vs. 3.20 ± 2.46; p = 0.000).

Prevention: The rating of the only item (Item 14) related to the prevention competency is significantly lower when assessed by the teacher than when assessed by the actress (p = 0.000).

Ethical - Legal Affairs: The rating of the only item (Item 18) related to ethical-legal affairs competency tends to be lower when assessed by the teacher than when assessed by the actress (p = 0.0736).

DiscussionThe study found a low correlation between the evaluations of dental students in the OSCE conducted by SPs and professors. The results indicated that SPs tended to give higher scores than the attending dentists. This discrepancy highlighted the need for more precise assessment tools and checklists to improve objectivity and accuracy in evaluations. In the OSCE, assessments are typically conducted by teachers.3,5 However, anyone involved in the test provided they are properly trained with a verified and carefully crafted checklist and have achieved adequate standardization, should be capable of administering this type of test and grading the student's performance accordingly.3

In 2023, Howey conducted an OSCE assessment involving dental hygiene students, where instructors also acted as developers, actors, and evaluators.10 Although this was a specific test for a bachelor's degree in dental hygiene, it shares similarities with our study, as the actors themselves, though teachers, were responsible for assessing the students. The student survey was completed after the clinical course and final grades were issued to mitigate potential conflicts of interest.

There are limited published data regarding students' perceptions of the impact that using instructors as SPs and examiners has on their overall experience and performance during the OSCE. In a pilot study of a dental OSCE, Donn et al.11 aimed to evaluate how the inclusion of an actor and evaluator from the university staff might influence the examination. Initially, the OSCE designers were concerned that interaction with a simulated internal university patient might compromise students' ability to maintain an appropriate relationship with the patient, thereby complicating the testing process. However, the authors ultimately reported that such concerns were unfounded, and students expressed comfort interacting with the SP.

Similarly, instructors in the current study raised concerns about the potential impact of students' pre-existing relationships with instructors on the authenticity of the student-SP interaction. However, they also acknowledged that students might benefit from the familiarity and comfort of seeing a known face during the assessment.

Many studies analyze potential factors influencing OSCE scores.12 Harasym et al. demonstrated that strictness or leniency on the part of examiners can lead to systematically high or low scores in a medical OSCE.13,14 The level of student performance also seems to influence the reliability of the grades given by examiners. Byrne et al. noted that good student performance was assessed more accurately than borderline performance.15 Yeates et al. found in several studies that good performance was rated higher if it followed an immediately preceding poor performance.16,17

Schleicher et al. demonstrated in a study involving several medical schools that local examiners from the university where the OSCE was conducted, as well as external examiners with more experience in OSCEs, assessed students' performance differently. Similarly, Park's study published in 2016 showed that part-time lecturers tended to give higher scores than full-time lecturers.18 This observation can be extrapolated to our study, as SPs, who have less subject knowledge than specialist teachers, awarded higher grades to students. While previous studies have explored how examiner characteristics, such as gender, may influence scoring patterns, this was not a variable analyzed in our study.14 Therefore, our discussion focuses on the main finding: that standardized patients consistently awarded higher scores than professors, particularly in clinical competencies such as diagnostic and therapeutic judgment.

Previous studies examining possible influencing factors and quality assurance of the test format are based on analyses of results from live observations or OSCE videos. While these analyses generally followed a standardized briefing of the examiners, they were still subject to influences from examinees that were not standardized, making it difficult to isolate the characteristics of the examiners for analysis.

Onwudiegwu et al. claim that untrained examiners pose a problem for both students and the examining body. A major concern is that most examiners are unfamiliar with the exam format and do not receive adequate prior training.5 In this study, we observed that the assessments made by the SPs did not align with the marks recorded by specialist teachers assessing the same OSCE station. Diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive judgment skills were assessed with higher scores by the SPs. All these areas require prior theoretical knowledge of the subject to judge whether or not the student's answers are correct. This observation aligns with findings by Khan et al., who emphasize that while standardized patients are effective at evaluating interpersonal aspects such as empathy and communication, their reliability significantly decreases when assessing technical clinical competencies that require specialized knowledge and training.6 Furthermore, the overall reliability of an OSCE is not only influenced by the quality of the checklist or the training of evaluators but also by the number of stations included in the examination. According to Khan et al. and Rodríguez & Sánchez-Ismayel, a minimum of 12 to 14 stations is necessary to achieve acceptable reliability, with 20 stations being ideal for high-stakes assessments.6,19

Strengths. This study presents several notable strengths that contribute to its overall validity and impact. Firstly, involving a substantial sample size of 210 students strengthens the findings' reliability. A larger participant pool enhances the statistical power of the study, allowing for more robust conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the OSCE evaluations in the dental education context.

The inclusion of SPs in the OSCE enhances the realism of the assessment process. SPs recreate authentic clinical situations, which enables the observation of students' communication skills and their ability to interact effectively with patients. This immersion in real-world scenarios adds depth to the evaluation and provides insights into the students' readiness for actual clinical practice.

Ultimately, the study significantly focuses on identifying discrepancies between the evaluations of SPs and professors, paving the way for improvements in assessment methods. By highlighting these discrepancies, the research encourages the development of refined assessment tools and checklists aimed at enhancing objectivity and accuracy in future dental evaluations, which is crucial for ensuring that graduates are well-prepared for clinical practice.

Weaknesses. The poor correlation between SP's and professors’ assessments raises several questions: Are some items in the checklist used for this OSCE somewhat misleading and therefore fail to compensate for the actors' deficiencies in theoretical knowledge? Were the professors at a disadvantage to the SPs in terms of assessing empathy, assertiveness, respect and interest, since they were not visualizing the interactions?

This study has several limitations that should be considered. Although standardized patients (SPs) received structured training—including rubric explanation, video calibration, and simulated scoring—they did not have formal clinical education. This may have limited their ability to apply diagnostic and therapeutic criteria with the same depth and consistency as faculty members. Additionally, all SPs were female, which could have introduced gender-related bias, particularly in the evaluation of communication and empathy. These factors may have contributed to the discrepancies observed between SP and professor assessments, especially in technical competencies.

Perhaps a clearer and more specific checklist that minimizes subjectivity in evaluating the different items to be examined would provide better correlation. For example, items could be divided into precise sections instead of using general terms. For instance, rather than asking students to “know and explain the difference between gingivitis and necrotizing gingivitis,” we could specify characteristics of each disease, such as “presence or absence of intense pain,” “presence of fever,” and “necrosis of the papilla.” This ensures greater objectivity and accuracy in the assessment. Onwudiegwu recommends a four-level scoring system: (Very Good - 3 points; Satisfactory/Good/Pass - 2 points; Poor - 1 point; Not Done - 0 points). This scoring system facilitates better discrimination between examinees.5

Regarding the “communication skills” section, we observed a similarity between the assessments by the actors and examining teachers. We believe these skills are more straightforward to evaluate without prior training, as anyone can instinctively assess how the student interacted and whether the communication was effective.

We must also consider whether the correlation of professors' and SP's evaluations is important in the first place. Perhaps SPs are in a better position to grade students on things like empathy, respect, interest and assertiveness, while the professors are in a better position to grade the clinical assessments.

As a novel and previously unstudied approach, this method presents a significant challenge in the design and planning of the OSCE. However, it also opens up many possibilities, such as reducing the number of staff needed and achieving cost savings. Additionally, it allows examiners to observe firsthand how the test is performed and to assess it as comprehensively and objectively as possible. Every innovation comes with its flaws and areas for improvement, and from this process, we learn and gain valuable insights.

In fact, we are currently advancing research in this area, modifying the sections of the checklist where there was a lack of agreement in the assessments. We also recognize the need to provide, alongside the pre-briefing of the actors, videos demonstrating potential student behaviors and various performance scenarios.

We recommend further studies to explore the discrepancies between evaluations by SPs and professors. Future research should focus on refining assessment tools and enhancing training for both SPs and examiners to improve the OSCE evaluation process.

If SPs are going to participate in student evaluations, more work should be done to assure that they have the knowledge base to do these evaluations effectively. The development of assessment scripts and very precise checklists may help to eliminate the discrepancies in grades observed in this study between SPs and specialist teachers. Or, it simply may be unrealistic to expect SP's and professors' grading of students to correlate in the first place.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Ethics approvalThe study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (protocol code CIPI 22.238).

Funding detailsThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors report no conflict of interest.