This study was designed to examine the moderating roles of perceived supervisor, coworker, and organizational support in the relationship between emotional labor and job performance in the airline service context. A sample of flight attendants working for one major airline company in South Korea participated in this study. The flight attendants’ official job performance data were provided by the airline company. For data analyses, a series of hierarchical moderated regression analyses were employed. The results showed differential moderation effects of the three sources of support at work. Specifically, the positive relationship between deep acting and job performance was strengthened by perceived supervisor and coworker support. The negative relationship between surface acting and job performance was exacerbated by perceived supervisor support, indicating the reverse buffering effect. Perceived organizational support showed only main effects on employee performance with no moderation effects.

Over the past decade, emotional labor has been a popular research topic among service academics because of the nature of service jobs requiring responding to guests with a smile at all times. Many service work settings have been used by researchers studying emotional labor: retail shops, hotels, restaurants, cruise ships, airline, and tour companies (Duke et al., 2009; Hur et al., 2015; Lee and Ok, 2012; Lee et al., 2015; Pizam, 2004; Seymour, 2000; Van Dijk et al., 2011). Emotional labor, “the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display” (Hochschild, 1983, p. 7), significantly influences both individual and organizational outcomes, ranging from employees’ physical/psychological well-being to their job satisfaction and job performance (e.g., Brotheridge and Lee, 2003; Hur et al., 2015; Morris and Feldman, 1997).

Since the concept was formulated, researchers have debated its sub-dimensions (Brotheridge and Lee, 2003; Diefendorff et al., 2005; Morris and Feldman, 1997) and its antecedents and consequences (Brotheridge and Grandey, 2002; Grandey, 2000; Pugliesi, 1999; Schaubroeck and Jones, 2000). Although the sheer number of articles on emotional labor has grown, most of them have focused on direct relationships involving predictors and outcomes of emotional labor. Little work has been conducted to examine moderating variables between employees’ emotional labor and their work outcomes (Duke et al., 2009). In particular, there appears to be a need to explore under what conditions employees’ emotional labor increases or reduces job performance.

Following in the footsteps of previous studies (Chen et al., 2012; Duke et al., 2009; Grandey, 2000; Hur et al., 2015; Nixon et al., 2011), we believe that the situation in which employees work can function as a moderator in the link between emotional labor and employee outcomes. One of the salient moderators identified is social support perceived by employees from various entities in the company. Workplace social support emanates from multiple sources, such as supervisors, coworkers and employing organizations (Kossek et al., 2011). For instance, Abraham (1998) suggested that workplace social support (i.e., supervisor, coworker, and organizational support) can attenuate the harmful effects of stress caused by emotional labor, pointing to the moderating effects of workplace social support on the relationship between emotional dissonance and job satisfaction. Studies by Duke et al. (2009) and Nixon et al. (2011) showed perceived organizational support to be a moderator between emotional labor and several job outcomes in retail service firms and a mobile phone company respectively. More recently, Chen et al. (2012) presented interactions between perceived supervisor support and emotional labor in the hotel work setting. However, coworker support has received less attention in the workplace support literature than has supervisor or organizational support (Ng and Sorensen, 2008). Similarly, the possible moderating role of perceived coworker support has been neglected in the emotional labor literature.

According to Leavy (1983), while workplace social support has been widely discussed in the literature, the concept of social support itself remains loosely defined. Furthermore, many studies have used the constructs of supervisor, coworker, or organizational support without providing a clear distinction between them. For example, perceived coworker support and perceived supervisor support have often been combined into a single variable in the examination of social support effects (e.g., Ducharme and Martin, 2000; Karatepe, 2010), despite supervisors and coworkers playing different roles in assisting frontline employees (Susskind et al., 2007). Furthermore, there is also a conceptual confusion between perceived supervisor support and perceived organizational support, with supervisor support being sometimes used as a proxy for organizational support (e.g., Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002). Therefore, we have attempted to fill the gap in the literature by examining the moderating roles of three types of support (e.g. supervisor, coworker and organizational support) on the emotional labor–job performance link within the same study.

Overall, the objectives and contributions of this article are three-pronged. First, it broadens the understanding of emotional labor and its outcomes by including the various sources of support as moderators within the same study. To make up for the missing but much-needed information on the moderating role of perceived coworker support in the emotional labor literature and to rule out any conceptual confusion between the various sources of support, this study included all three major support entities (organization, supervisors and coworkers) in the workplace and treated them independently in the proposed model. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to introduce these three important sources of social support in one study with emotional labor as a stressor. By addressing this issue, this study may develop a clearer understanding of the effects of workplace social support on the emotional labor and job performance link. Second, we took into consideration the differences between the two acting modes of emotional labor (i.e., deep acting and surface acting), and hypothesized interactions between the three sources of support and each acting mode to provide a more comprehensive view on the roles of different support moderators. Finally, following Hochschild (1983), this study used flight attendants from one airline company in South Korea as study subjects. A dataset of fight attendants in South Korea, characterized as a strong collectivist culture (Hofstede et al., 2010), may provide an opportunity for cultural comparison in contrast to Western individualism.

In summary, this study is designed to answer the following three research questions: (1) do work-based sources of support function as moderators between contact employees’ emotional labor and job performance in the airline service context?; (2) what are the differences between the three work-based support moderators?; and (3) can we conclude that the three sources of workplace social support are unique and distinctive entities? The following section explores the relevant literature and presents the proposed hypotheses.

Literature review and hypotheses developmentEmotional labor and its consequencesHochschild (1983) coined the term emotional labor after observing the tendency of flight attendants to express socially desirable emotions in a job situation in compliance with the display rules of the organization. The act of displaying socially-desired emotions has been argued to be a form of “emotional labor” since it demands an effort on the part of employees to manage their emotional expression or change their inner feelings in order to facilitate task effectiveness and employee effectiveness (Hochschild, 1983). Although there are many definitions of emotional labor in the literature, the regulation of feelings and expressions at work are the common understanding of the concept (Ashforth and Humphrey, 1993; Grandey, 2000; Hochschild, 1983).

Emotional labor requires employees to use emotion regulation strategies at work for resolving emotional dissonance that is generated from displaying organizationally desired emotions regardless of one's felt emotions (Ashforth and Humphrey, 1993; Hochschild, 1983; Grandey, 2000; Morris and Feldman, 1997). Researchers have focused on two types of emotional regulation strategy pursued by employees, namely deep acting and surface acting (Ashforth and Humphrey, 1993; Hochschild, 1983). Deep acting is an antecedent-focused regulation of emotion, taking place before emotions develop, and aims to alter the situation or the perception of a situation (Grandey, 2000; Gross, 1998). Deep acting appears authentic to the audience because it requires putting oneself in another's shoes, often labeled as “good faith” (Diefendorff et al., 2005). Conversely, surface acting is a response-focused emotion regulation that takes place after emotions have developed; emotional expressions are managed without making any adjustment to actual feelings (Grandey, 2000; Gross, 1998). Surface acting focuses on the response of customers, only modifying the expressions visible on the surface. It is called “bad faith” because it entails the deception of customers by feigning emotions (Rafaeli and Sutton, 1987). Thus, deep acting is a more active emotional expression since it operates by actually experiencing desired emotions through “good faith”, which has a distinctly different mechanism from surface acting.

Due to the contradictory characteristics of deep acting and surface acting, prior research has suggested that deep acting and surface acting have differential effects on employee outcomes, such as job attitudes, job satisfaction, job burnout, and employees’ performance and wellbeing (Brotheridge and Grandey, 2002; Grandey, 2000; Grandey et al., 2005; Lee and Ok, 2012; Pugliesi, 1999; Schaubroeck and Jones, 2000). Surface acting generally creates emotional dissonance, a discrepancy between inner and outward feelings, which drains one's emotional resources over time, increasing the likelihood of burnout, a combination of exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy, and at the same time diminishing the sense of job satisfaction (Grandey, 2000; Grandey et al., 2005; Hülsheger and Schewe, 2011; Judge et al., 2009; Morris and Feldman, 1997; Pugliesi, 1999). According to conservation of resources (COR) theory (e.g. Hobfoll et al., 1996), surface acting requires a great amount of cognitive and motivational resources, and depletes emotional reserves, which in turn negatively influences job satisfaction (e.g. Grandey et al., 2005; Hülsheger and Schewe, 2011; Nixon et al., 2011) and job performance (Judge et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2011).

On the other hand, matched internal and external feelings derived from deep acting reduce emotional dissonance and the authentic expression of self leads to increased professional efficacy (Brotheridge and Lee, 2002) and a decrease in burnout (Chen et al., 2012). Indeed, deep acting develops genuine positive emotions (Chen et al., 2012), leading to a greater job satisfaction (Nixon et al., 2011). In addition, authenticity of emotional display achieved through deep acting positively affects job performance (Hülsheger and Schewe, 2011). Previous research has suggested that deep acting tends to create positive work outcomes, such as customer satisfaction and improved job performance (e.g. Grandey et al., 2005; Hennig-Thurau et al., 2006). For instance, employees engaged in deep acting are more likely to express their genuine emotions to customers in fulfilling their responsibilities, which in turn increases sales (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2006).

Moderating hypothesis of social supportSocial support (i.e., organization, supervisor and coworker support) is loosely defined as “the availability of helping relationships and the quality of those relationships” (Leavy, 1983, p. 5). Researchers have explained how social support links to one's well-being via two routes (Cohen and Wills, 1985; Ducharme and Martin, 2000). One model views social support as a main effect; it benefits people by decreasing the level of strain regardless of the amount of stress experienced. The other model proposes that social support interacts with a stressor to affect the felt strain. This interactive effect is commonly referred to as a buffering effect, where ‘buffering’ denotes protection from the harmful influence of stressful events (Cohen and Wills, 1985). Although the moderating role of social support is disputed due to inconsistent findings ranging from significant effects to non-significant effects (and even reverse moderation effects), the moderating hypothesis of social support by and large remains strong (Beehr et al., 1990; Fenlason and Beehr, 1994).

Social support has long been identified as a resource that enables people to cope with stress (Hobfoll, 2002; Fenlason and Beehr, 1994). People who have more social companionship have more access to instrumental assistance, esteem support, and the like (Cohen and Wills, 1985). Thus, the fundamental logic of the moderating hypothesis of social support in the workplace is that workers who have supportive organizations, supervisors and peers, for example, can depend on them when times are difficult at work. Thanks to supportive others, employees may feel that the work stressor in question is less problematic, which may mitigate the contribution of the stressor to employee strain. In contrast, employees who do not have supportive relationships can suffer more severely from the negative effects of work stressors.

Supervisor support as a moderator between emotional labor and work performanceConforming to the definition of social support introduced by Leavy (1983), this study defines perceived supervisor support as employees’ beliefs about the degree to which the quality of helping relationships derived from supervisors is available. While there are many feasible sources of support at work, supervisors in charge of employee performance and evaluation are recognized as the most influential support entity in the workplace (Beehr et al., 1990; Ng and Sorensen, 2008; Russell et al., 1987). The main (direct) effects of perceived supervisor support on burnout (Beehr et al., 1990; Russell et al., 1987) and the moderating roles of perceived supervisor support in multiple stressor and strain relationships (e.g., Beehr et al., 1990: role stressors and job satisfaction/satisfaction with supervisors/depression; Fenlason and Beehr, 1994: underutilization of skills/qualitative underload and psychological strain) have been well documented.

As emotional labor emerged as one of the critical stressors for customer contact employees (Brotheridge and Grandey, 2002; Grandey, 2000; Pizam, 2004; Pugliesi, 1999; Schaubroeck and Jones, 2000), scholars began to test the moderating hypothesis of perceived supervisor support in the emotional labor context. For example, Chen et al. (2012) found that the two emotional acting strategies are inversely associated with employee strain, implying that perceived supervisor support intensifies the desirable consequences of deep acting and attenuates (buffers) the harmful outcomes of surface acting: (1) supervisor support weakens the positive relationship between surface acting and burnout; (2) supervisor support weakens the negative relationship between surface acting and job satisfaction; (3) supervisor support strengthens the positive relationship between deep acting and job satisfaction; and (4) supervisor support strengthens the negative relationship between deep acting and burnout.

Unlike Chen et al. (2012), who examined the moderating effect of perceived supervisor support on the relationship between emotional labor and job satisfaction/burnout, our study proposed that supervisor support serve as an enhancing mechanism in the positive relationship between deep acting and job performance and a buffering mechanism in the negative relationship between surface acting and job performance. Our rationale is that because supervisors are a particularly powerful source of social support, their encouragement and support may bolster deep actors’ internalization of display rules and motivate them to excel in guest interactions across situations. Simultaneously, having supervisors who are supportive of and caring about their subordinates may direct surface actors to reappraise challenging encounters and improve their performance with less use of fake emotions. Two moderation hypotheses regarding perceived supervisor support are presented below:Hypothesis 1a The relationship between deep acting and job performance varies based upon the extent of perceived supervisor support, such that the positive effect of deep acting on job performance is stronger for employees with a high level of perceived supervisor support than a low level of perceived supervisor support. The relationship between surface acting and job performance varies based upon the extent of perceived supervisor support, such that the negative effect of surface acting on job performance is weaker for employees with a high level of perceived supervisor support than a low level of perceived supervisor support.

Aligned with the definition of perceived supervisor support, perceived coworker support is defined as employees’ beliefs about the degree to which the quality of helping relationships derived from peers is available. Findings of perceived coworker support as a moderator in the stressor and strain relationship have been mixed. In a study of teacher burnout (Russell et al., 1987), neither main effects nor interactive effects of perceived coworker support were found, in contrast with the findings of the significant effects of perceived supervisor support. Using full-time employees from a broad spectrum of occupations across the U.S., Ducharme and Martin (2000) detected only main effects for perceived coworker support, although the researchers hypothesized a buffering role for coworker support in the adverse influence of unrewarding work on job satisfaction. A comparative study of the effect of a variety of social support (supervisors, coworkers, friends and family) on occupational stress by Fenlason and Beehr (1994) demonstrated perceived coworker support as a reverse buffer (increasing strain) in a sample of professional secretaries. Van Emmerik et al. (2007) found perceived peer support as a buffer of the negative relationship between an unsafe climate and employee dedication and organizational commitment.

Going against most of the existing literature, Susskind et al. (2007) attributed a greater predictive power to coworker support than supervisor support for guest orientation in the restaurant work environment. However, their structural model did not test the interactive effects of social support on guest orientation. Brotheridge and Lee (2002) found that perceived coworker support is positively related to emotional display rules. They argued that while employees are trying to figure out their role identity in their organization, coworkers become compelling referents. In other words, coworkers become a means of social influence that is conducive to the internalization of service work roles including display rules.

None of these prior studies have attempted to examine the moderating role of perceived coworker support in the relationship between emotional labor and employee strain or performance. However, based on Brotheridge and Lee (2002)’s logic, along with the fundamental notion of social support as a coping resource it seems reasonable to assume a moderating role of coworker support. Coworker support includes emotional concern, instrumental aid, information, or appraisal (Carlson and Perrewe, 1999). These types of support from coworkers encourage employees to solve job-related problems with more efficiency and decrease customer-related social stressors and emotional exhaustion (Karatepe et al., 2010; Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004). Thus, we propose that the negative effect of surface acting on job performance is likely to be attenuated when a high level of coworker support is perceived, whereas the positive effect of deep acting on job performance is likely to increase. More specifically, deep actors, with support from coworkers who are presumably engaged in deep acting, are likely to reinforce display rules in their heart, continuing to excel in their service performance. Even surface actors may possibly change their emotional regulation strategy into deep acting by learning deep acting behaviors from coworkers who are frequently performing deep acting. Thus, we propose the following two moderation hypotheses regarding perceived coworker support:Hypothesis 2a The relationship between deep acting and job performance varies based upon the extent of perceived coworker support, such that the positive effect of deep acting on job performance is stronger for employees with a high level of perceived coworker support than a low level of perceived coworker support. The relationship between surface acting and job performance varies based upon the extent of perceived coworker support, such that the negative effect of surface acting on job performance is weaker for employees with a high level of perceived coworker support than a low level of perceived coworker support.

Perceived organizational support is widely defined as employees’ beliefs about the degree to which their organization values their contributions and cares about them (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002). Conceptually, perceived organizational support is developed by employees’ tendency to assign human characteristics to their organizations (Levinson, 1965). Since organizational support involves the provisions of an organization, such as appropriate working conditions and assignments for its employees (Eisenberger et al., 1986), it triggers a willingness amongst employees to reciprocate by their efforts and contributions for their organizations. According to the social exchange theory that refers to employees’ voluntary behaviors of reciprocity in proportion to received support from their organization, employees with higher levels of perceived organizational support are more likely to work harder to perform the desired action (Blau, 1964).

Limited moderating roles for organizational support have been found in the relationships between exposure to AIDS patients and negative employee mood (George et al., 1993), between work-family conflict and organizational commitment (Casper et al., 2002), and between role stressors and burnout (Jawahar et al., 2007). A close reflection of the current study is shown in Duke et al. (2009) and Nixon et al. (2011). Duke et al. reported that perceived organizational support buffers the negative impact of emotional labor on both satisfaction and performance. Unlike Duke et al. (2009), Nixon et al. (2011) divided emotional labor into deep acting and surface acting, in accordance with the more recent conceptualization of emotional labor. The researchers discovered that with higher levels of perceived organizational support, the positive influence of deep acting on a few work outcomes, such as mental wellbeing, job satisfaction, and professional efficacy, becomes stronger, but also found that the moderating pattern involving surface acting is largely in the opposite direction to their hypotheses (e.g., stronger negative relationships between surface acting and satisfaction with growing organizational support).

In harmony with the earlier rational of perceived supervisor support and perceived coworker support, we predict that under a high level of perceived organizational support, the negative impact of surface acting on job performance would be decreased whereas the positive impact of deep acting on job performance would be strengthened. Those who postulated significant roles of perceived organizational support in the stressor and strain link interpreted organizational support as a coping mechanism. The firm itself can provide instrumental or esteem support for employees through company policies and procedures (Jawahar et al., 2007). For example, supportive companies are likely to have clear guidelines governing guest interactions with training on how to handle customer demands and complaints. Thanks to a concrete foundation in customer service, employees may feel more confident during service encounters and express organizationally desired emotions. Such confidence can reinforce deep actors’ excellent performance and deter surface actors’ poor performance. Thus, we put forward the following moderating hypotheses for perceived organizational support:Hypothesis 3a The relationship between deep acting and job performance varies based upon the extent of perceived organizational support, such that the positive effect of deep acting on job performance is stronger for employees with a high level of perceived organizational support than a low level of perceived organizational support. The relationship between surface acting and job performance varies based upon the extent of perceived organizational support, such that the negative effect of surface acting on job performance is weaker for employees with a high level of perceived organizational support than a low level of perceived organizational support.

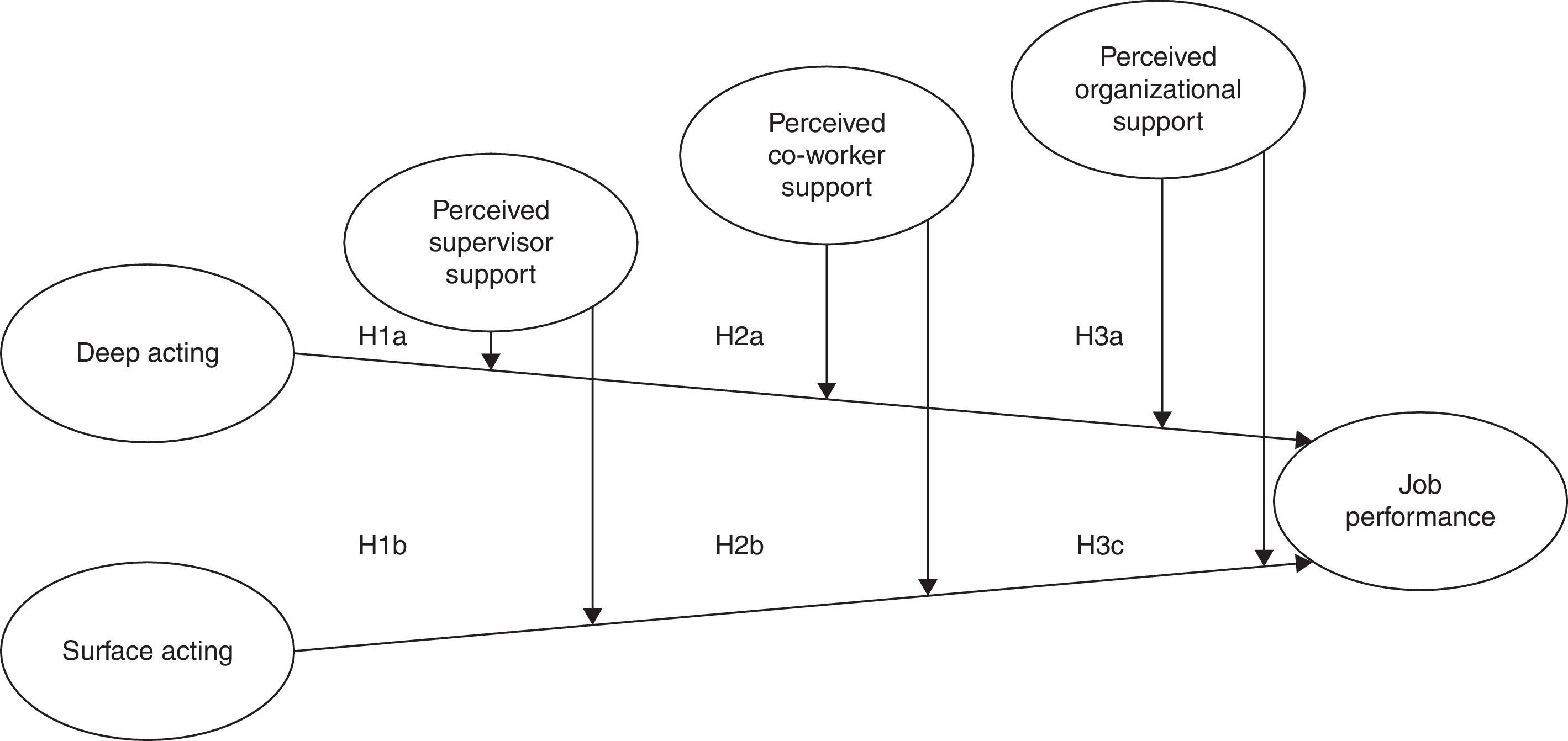

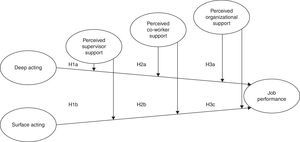

Fig. 1 provides a visual depiction of the proposed relationships between two emotional labor strategies, job performance, and three work-based support moderators.

Research methodologyData collection and respondent characteristicsThe employees at a single airline company headquartered in one of the major metropolitan cities in South Korea participated in this study. With company approval, 150 flight attendants were invited to participate in this study. The cover page of the self-administered instrument included the purpose of this study and confidentiality of the information. Of 150 questionnaires distributed, 126 questionnaires were returned to the authors by mail. Of those 126 returned (response rate: 79.3%), 119 questionnaires were usable after list-wise deletion. A preliminary analysis revealed that 89.9% of the respondents were females and the remainder were males. Respondents’ age ranged from 22 to 39 with an average age of 27 years (SD=3.18). All respondents had at least some college education and a majority of the respondents (88.2%) had earned a bachelor's degree. The respondents had worked for their company for an average of 4.68 years (SD=2.95). The respondent profile of this study reflects the typical characteristics of flight attendants in the airline industry in South Korea.

MeasuresAll measures selected for this study were written originally in English. To ensure the quality of translation in Korean, we used the back-translation method recommended by Brislin (1970). All survey items were assessed on five-point scales. The emotional labor scale came from Diefendorff et al. (2005) and included three items for deep acting (e.g., “I show feelings to customers that are different from what I feel inside”) and three items for surface acting (e.g., “I work hard to feel the emotions that I need to show to customers”). To assess perceived organizational support, a three-item measure was adapted from Eisenberger et al. (2001) (e.g., “My organization really cares about my well-being”). Perceived supervisor support was measured with three items originating from Babin and Boles (1996) (e.g., “My supervisors really stand up for people”). Perceived coworker support was assessed with three items adopted from Ducharme et al. (2008) (e.g., “When I encounter a problem, I usually seek help from my coworkers”).

For job performance, we utilized each employee's actual (official) performance evaluation obtained from the participating company's human resources department (i.e., annual formal performance appraisals), similar to Harris et al. (2007). The target organization evaluates its members’ job performance in three stages. First, the flight attendants are rated by their supervisors using a range of measures which reflect the quality of their work, the level of customer satisfaction, and the contributions they make to the organization. Due to the inherent difficulty of directly assessing their subordinates, supervisors utilize a range of objective markers such as the number of compliments and complaints received from customers, together with any tangible service improvements made by the employees. Attendants are then given a score from one to five – 1 (weak), 2 (fair), 3 (satisfactory), 4 (well), and 5 (great), after which the Department of Human Resource Management meets to consider the supervisors’ performance appraisals and assign one of five grades to each flight attendant using a forced distribution system: D (very inferior), C (inferior), B (average), A (superior), and S (very superior). Accordingly, we coded each grade into a score (D [1] to S [5]).

ResultsMeasurement evaluationsSeveral reliability and validity tests were conducted to assess the quality of five measures filled by respondents (surface acting, deep acting, perceived supervisor support, perceived coworker support, and perceived organizational support). First, the reliability of the measures was evaluated with Cronbach's alpha coefficients. Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranged from .81 to .90, all greater than the cut-off value of .70 (Nunnally, 1978).

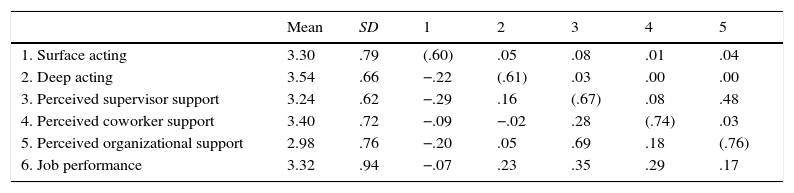

Confirmatory factor analysis was then performed to evaluate the convergent and discriminant validity of the scales with M-plus 5.1 software. The measurement model demonstrated a good fit: χ(80)2=142.51, p<.05, CFI=.94, TLI=.92, RMSEA=.08, SRMR=06. Similar to the results of the Cronbach's alpha coefficients, all measures exhibited strong reliability with composite reliability scores ranging from .82 to .91. Factor loadings of all items in the five scales exceeded .68, with t-values greater than 2.58 (p<.01), providing evidence of convergent validity for all measures. We checked the conditions for discriminant validity among the five constructs as suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981). The average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct was greater than the squared correlations between the focal construct and any others, suggesting the distinctiveness of all five constructs. The descriptive statistics, correlations, squared correlations and AVEs of the study variables are shown in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, correlations, squared correlations and AVEs of study variables.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Surface acting | 3.30 | .79 | (.60) | .05 | .08 | .01 | .04 |

| 2. Deep acting | 3.54 | .66 | −.22 | (.61) | .03 | .00 | .00 |

| 3. Perceived supervisor support | 3.24 | .62 | −.29 | .16 | (.67) | .08 | .48 |

| 4. Perceived coworker support | 3.40 | .72 | −.09 | −.02 | .28 | (.74) | .03 |

| 5. Perceived organizational support | 2.98 | .76 | −.20 | .05 | .69 | .18 | (.76) |

| 6. Job performance | 3.32 | .94 | −.07 | .23 | .35 | .29 | .17 |

Notes: SD=standard deviation. AVE=average variance extracted. All items are measured with a 5-point scale. Job performance is a one-item measure. AVEs appear in parentheses on the diagonal. Correlations are below the diagonal. Squared correlations are above the diagonal.

Common method variance is a potentially serious threat in behavioral research with single-informative, self-reported surveys (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Common method bias can be controlled through both procedural and statistical remedies (Podsakoff et al., 2012). As stated in the data collection and measurement sections, we implemented procedural remedies by guaranteeing confidentiality of information, by improving the wording of each item (back-translation), and most importantly by separating the sources of information on the independent and dependent variables (Podsakoff et al., 2012). In addition to these procedural efforts, we performed Harman's one-factor analysis, a statistical remedy that is popularly used for diagnosing method bias. We applied a confirmatory factor-analytic approach to conduct Harman's one-factor analysis. Harmon's one-factor model demonstrated a very poor model fit (χ(93)2=870.69, p<.05, CFI=.23, TLI=.13, RMSEA=.27) and the chi-square difference test indicated that the one-factor model fits the data significantly worse than the original five-factor model, consisting of surface acting, deep acting, supervisor support, coworker support and organizational support (excluding job performance) (Δχ(13)2=728.18, p<01). This statistical procedure provided the evidence that a single method-driven factor does not represent our data. In other words, our data are not affected by common method bias.

Hypotheses testingHierarchical moderated regression analyses were performed to test the research hypotheses. Too many support providers in a single regression model may neutralize the positive impact of support on outcome variables (McIntosh, 1991). Therefore, three separate regression models were constructed with each support as a focal moderator. In the first step, gender and age were entered as control variables. Gender and age were selected because these two demographic variables most often appeared to be related to emotional regulation strategies (e.g., Dahling and Perez, 2010; Hochschild, 1983; Schaubroeck and Jones, 2000). In the second step, two acting strategies and one selected support were entered as main effect variables. The final step included two cross-product terms representing interactions between two acting modes and the chosen support. To minimize the possibility of multicollinearity, we centered all main effect variables to calculate interaction terms (Edward and Lambert, 2007).

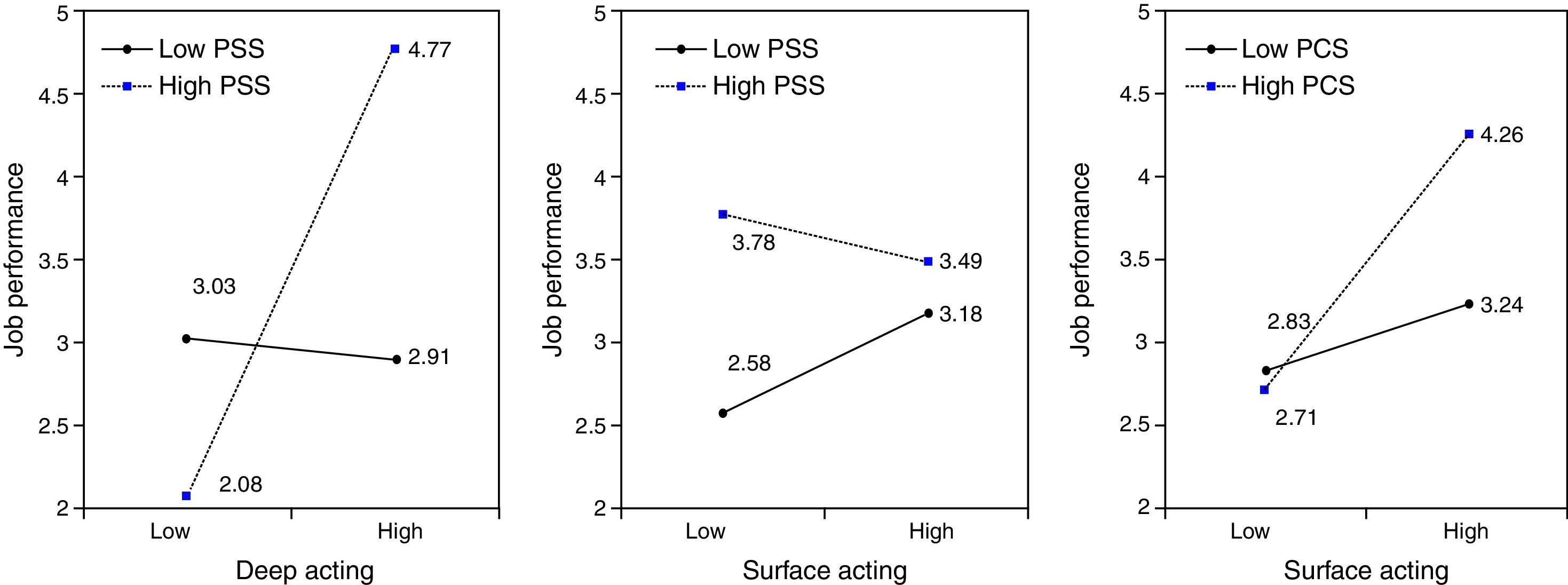

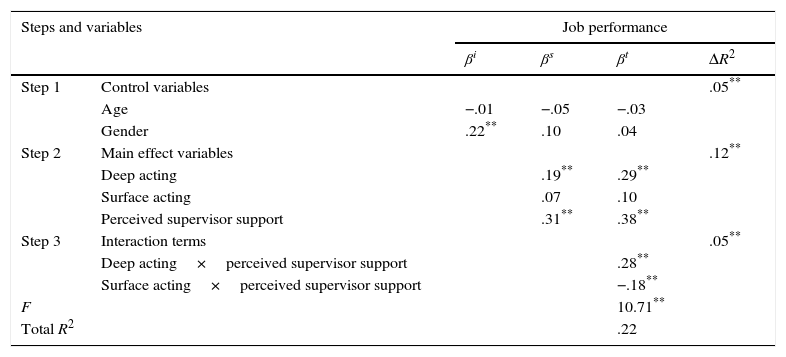

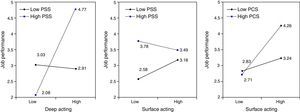

Hypotheses 1a and 1b proposed perceived supervisor support as a moderator between two emotional labor strategies and job performance (Table 2). In step 1, of the two controls (gender and age), gender (β=22, p<.01) predicted job performance. In step 2, of the three main effects (deep acting, surface acting and supervisor support), deep acting (β=19, p<.01) and supervisor support (β=31, p<.01) were significant determinants of job performance, accounting for a significant portion of the variance beyond the control variables (ΔR2=.12, p<.01). In the final step, the entry of two interaction terms (deep acting×supervisor support and surface acting×supervisor support) contributed unique variance to the regression model (ΔR2=.05, p<.01) and both interactions were significant. To understand the nature of the significant deep acting×supervisor support interaction (β=28, p<.01), we plotted job performance scores at combinations of the mean±1 SD (high and low levels) for both deep acting and supervisor support measures, as recommended by Hayes and Matthes (2009). The interaction plot (Fig. 2) demonstrated that the positive relationship between deep acting and job performance is strengthened with a high level of perceived supervisor support (simple slope=81, p<.01) compared to a low level (simple slope=−.04, n.s.), lending support to Hypothesis 1a.

Hierarchical regression results for perceived supervisor support and emotional labor predicting job performance.

| Steps and variables | Job performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βi | βs | βt | ΔR2 | ||

| Step 1 | Control variables | .05** | |||

| Age | −.01 | −.05 | −.03 | ||

| Gender | .22** | .10 | .04 | ||

| Step 2 | Main effect variables | .12** | |||

| Deep acting | .19** | .29** | |||

| Surface acting | .07 | .10 | |||

| Perceived supervisor support | .31** | .38** | |||

| Step 3 | Interaction terms | .05** | |||

| Deep acting×perceived supervisor support | .28** | ||||

| Surface acting×perceived supervisor support | −.18** | ||||

| F | 10.71** | ||||

| Total R2 | .22 | ||||

Notes: βi=standardized beta with control variables; βs=standardized beta with controls and predictor variables; βt=standardized beta after all variables have been entered. Gender: female=0 and male=1.

* p<.05.

The plot was also drawn to examine the significant surface acting×supervisor support interaction (β=−.18, p<.05) following the same procedure (Fig. 2). The simple slope test revealed that the moderating pattern is in the opposite direction of Hypothesis 1b. Those reporting a low level of perceived supervisor support have a significant, modest positive relationship between surface acting and performance (simple slope=18, p=.07) while their counterparts reporting a high level of perceived supervisor support have no significant relationship between surface acting and performance (simple slope=−.07, n.s.). Due to this reverse moderation effect, Hypothesis 1b was rejected.

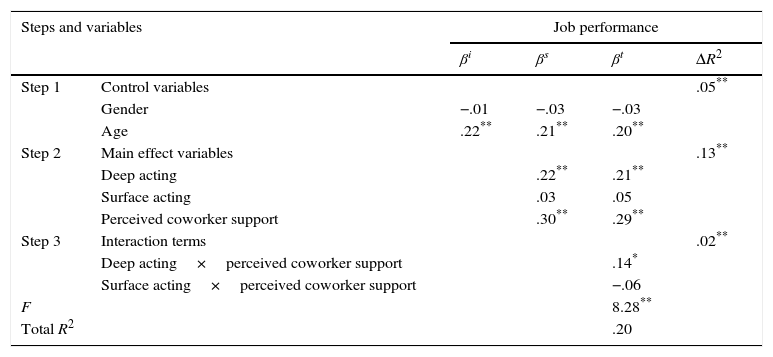

The second set of hypotheses (Hypotheses 2a and 2b) pertains to perceived coworker support as a moderator between two emotional acting modes and job performance. As depicted in Table 3, of the three main effects (deep acting, surface acting, and coworker support), deep acting (β=22, p<.01) and coworker support (β=30, p<.01) were significant predictors of employees’ job performance, adding a significant increment of R2 (ΔR2=.13, p<.01) to the regression equation. In the final step (ΔR2=.02, p<.01), the deep acting×coworker support interaction (β=14, p<.05) was significant while the surface acting×coworker support interaction was not significant. The interaction plot (Fig. 2) concurred with our prediction of Hypothesis 2a. The positive relationship between deep acting and performance was strengthened with a high level of perceived coworker support (simple slope=.47, p<01) than with a low level of perceived coworker support (simple slope=.12, n.s.). Thus Hypothesis 2a was supported and Hypothesis 2b was rejected due to the insignificant interaction effect.

Hierarchical regression results for perceived coworker support and emotional labor predicting job performance.

| Steps and variables | Job performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βi | βs | βt | ΔR2 | ||

| Step 1 | Control variables | .05** | |||

| Gender | −.01 | −.03 | −.03 | ||

| Age | .22** | .21** | .20** | ||

| Step 2 | Main effect variables | .13** | |||

| Deep acting | .22** | .21** | |||

| Surface acting | .03 | .05 | |||

| Perceived coworker support | .30** | .29** | |||

| Step 3 | Interaction terms | .02** | |||

| Deep acting×perceived coworker support | .14* | ||||

| Surface acting×perceived coworker support | −.06 | ||||

| F | 8.28** | ||||

| Total R2 | .20 | ||||

Notes: βi=standardized beta with control variables; βs=standardized beta with controls and predictor variables; βt=standardized beta after all variables have been entered. Gender: female=0 and male=1.

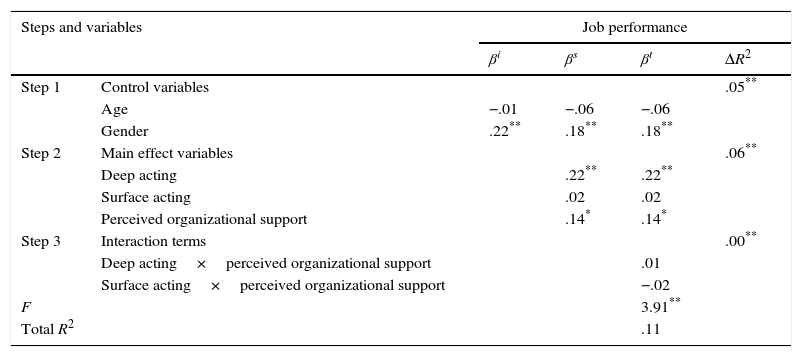

The third regression (Table 4) was conducted to evaluate the moderating role of perceived organizational support between two emotional labor strategies and job performance (Hypotheses 3a and 2b). Deep acting (β=22, p<.01) and organizational support (β=14, p<.05) showed significant main effects on performance while surface acting had no effect on performance. These main effects produced a significant increase in the variance explained for job performance (ΔR2=.06, p<.01). In the final step, neither interaction term (deep acting×organizational support and surface acting×organizational support) was found significant, rejecting the last set of hypotheses.

Hierarchical regression results for perceived organizational support and emotional labor predicting job performance.

| Steps and variables | Job performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βi | βs | βt | ΔR2 | ||

| Step 1 | Control variables | .05** | |||

| Age | −.01 | −.06 | −.06 | ||

| Gender | .22** | .18** | .18** | ||

| Step 2 | Main effect variables | .06** | |||

| Deep acting | .22** | .22** | |||

| Surface acting | .02 | .02 | |||

| Perceived organizational support | .14* | .14* | |||

| Step 3 | Interaction terms | .00** | |||

| Deep acting×perceived organizational support | .01 | ||||

| Surface acting×perceived organizational support | −.02 | ||||

| F | 3.91** | ||||

| Total R2 | .11 | ||||

Notes: βi=standardized beta with control variables; βs=standardized beta with controls and predictor variables; βt=standardized beta after all variables have been entered. Gender: female=0 and male=1.

In this study, we predicted three sources of social support as enhancing moderators in the positive relationship between deep acting and job performance. Overall, for customer contact employees who are willing to act in good faith, aligning their feelings with company display rules in a genuine manner, perceived supervisor and coworker support appeared to be a significant boost for their performance. Unlike the study of Nixon et al. (2011), the current study failed to confirm perceived organizational support as an enhancing moderator in the positive link between deep acting and job performance. Compared to the retail setting of Nixon et al.’s study, airline service requires a substantial amount of team work and coordination to satisfy an aircraft full of passengers. The insignificant moderation effect of organizational support in this study may be attributable to the above characteristics of airline service. Flight attendants have direct contact with passengers while offering a high quality of service for a long period of time. Especially during international service, flight attendants spend most of their work hours with their supervisors and coworkers in the aircraft cabin, interdependently handling the varied temperaments and diverse demands of their passengers. Added to this, the frequency with which they fly may cause attendants to experience a degree of alienation and decreases their sense of connection to the company. Thus, while supervisors and coworkers are physically around to help deep acting employees improve their work efficacy, the fact that organizational support is distant for deep actors indicates that support is not immediately available. In this study, relatively high mean ratings of perceived supervisor (M=3.24) and coworker support (M=3.40), as opposed to the low rating of perceived organizational support (M=2.93), partly justify our rationale. Despite no moderating effect, it should be noted that perceived organizational support has a positive main effect on job performance. This indicates that contact employees still benefit from organizational support regardless of the amount of emotional labor they perform.

Interactions between surface acting and workplace social supportThe same three sources of workplace support were postulated as buffers in the negative relationship between surface acting and performance. In general, the results of this study are not supportive of the buffering roles of work-based support for surface acting. Moreover, one unexpected reverse buffering appeared. When perceived supervisor support is high, surface actors’ performance decreases (although the simple slope is insignificant); and when perceived supervisor support is low, surface actors fare better with a modest increase in their performance. Periodically, the literature has shown a reverse buffering effect of social support on various outcomes, such as job stress, job dissatisfaction, and well-being (e.g., Fenlason and Beehr, 1994; Kickul and Posig, 2001).

To reconcile the mixed findings of social support as a moderator, scholars have emphasized the importance of identifying the amount or adequacy of social support or the contents of communications (positive or negative) between supportive sources and stressed individuals. Too much support may not necessarily create positive work-related outcomes (McIntosh, 1991) and the negative contents of communications can result in reverse buffering effects (Fenlason and Beehr, 1994). We speculate that airline service supervisors may notice surface actors’ performance is superficial thereby bringing in help to improve the quality of service to passengers. Supervisors may offer more assistance to surface actors than to deep actors because of the surface actors’ poor performance. Supervisors may also stress the importance of display rules and those conversations may not always be in a positive tone. Supervisors’ greater attention to surface actors may be interpreted as distrust in surface actors’ performance and this perception may prompt perceived supervisor support to be a reverse buffer, further exacerbating or stagnating surface actors’ service behavior.

Alternatively, we can explain reverse buffering using Wilk and Moynihan's (2005) empirical findings. Wilk and Moynihan (2005) showed that supervisors’ emphasis on display rules is taxing for those low in career identity, who are likely to be surface actors. The researchers argued that supervisors can be a source of stress rather than support for certain employees and the result of reverse buffering for surface actors may reflect their assertion regarding the dual role of supervisors.

Distinctiveness of the three entities of workplace social supportIn the past, the three support entities were frequently used in combination. In this study, correlations between the three sources of social support are fairly low with the exception of one case. A high correlation (r=69) between perceived supervisor support and perceived organizational support is to some extent in line with the view arguing for supervisor support as an organizational support because supervisors are agents of the organization (Eisenberger et al., 2004). However, note that we examined the discriminant validity of all measures (see Section “Measurement evaluations”). In addition, correlations between job performance and perceived supervisor support (r=35) and perceived organizational support (r=17) are clearly different, not to mention a disparity in their moderation effects. This suggests that the two are correlated but distinctive entities. Overall, the result of this study demonstrates the necessity of differentiating the three work-based support entities in order to evaluate their roles in the organization accurately.

ConclusionsTheoretical contributionIn the emotional labor literature, the testing of moderating effects is scant. This study was conducted in an attempt to fill this gap. In addition to perceived organizational and supervisor support reported in previous articles (Chen et al., 2012; Duke et al., 2009; Nixon et al., 2011), perceived coworker support, often overlooked due to its weak influence, was found to be a promising moderator in the emotional labor context in airline service. This suggests that coworker support may be as beneficial as other types of support at work in certain industries or job contexts. This study also extends the body of knowledge on the commonly accepted moderating hypothesis of social support by revealing the versatility of the theory in the relatively new emotional labor and job performance link.

The most noteworthy theoretical contribution of this study lies in the comparative analysis of the moderating effects of three critical workplace support entities on stressful service jobs requiring emotional acting. Prior studies provided fragmentary information because scholars typically explored the effect of one particular support entity in their emotional labor research. In summary, in this study, individuals working close to customer contact employees, namely supervisors and coworkers, were recognized as more salient sources of support than the firm itself, and deep acting employees were found to be more receptive to social support at work, strengthening their job performance.

Finally, our study contributes to a deeper understanding of emotional labor by examining the role of workplace social support in two emotional regulation strategies required for job performance. Different from previous studies that have conceptualized social support as moderators in the association between emotional labor and emotional exhaustion or job satisfaction (e.g. Grandey, 2000; Hur et al., 2015), this study postulates three types of workplace support as moderators in the relationship between emotional labor and job performance. In short, this study highlighted the importance of employees’ perceptions of their support in the emotional labor and job performance link by including the various sources of support as moderators in the same study.

Managerial implicationsAs with airline service, many service businesses experience a large group of customers during peak hours and coworker collaboration may become critical for the success of the operation. For example, large hotel companies often conduct daily meetings to inform employees of major events, seeking peer collaboration throughout the day. Ritz Carlton, the hotel company renowned for its customer service, has a “lineup” system where employees not only review everyday events but share “wow stories” (Gallo, 2007). Those stories often highlight the importance of teamwork to meet the needs of their guests. As seen in the practice of Ritz Carlton, it may be an excellent strategy for service employees to have a forum where they spread success stories, and whenever needed, for customer contact employees to resolve work-related issues as a team. Through these kinds of stories, customer contact employees become familiar with such admirable coworkers, possibly further strengthening service attitudes. It is also recommended that service companies with highly fluctuating business demands confer rewards based on team performance, in addition to traditional awards for exemplary, high performing individual employees. Team-based awards are likely to send the message that the company values teamwork and to foster collaboration among coworkers.

The opposite moderating role of perceived supervisor support between surface acting and job performance signals that managers should use different tactics while supervising surface actors. For surface actors, it may be wise to offer support without creating the impression of overwhelming support. The ultimate goal for supervisors who have surface actors should be to transform them into deep actors. This may require highly adept coaching and communication skills. Service firms such as airlines and restaurants should consider designing an in-house training program or hiring a third party for their supervisors to refine their managing skills and be sensitive to the impact of their actions on their subordinates.

Another important implication stems from the fact that social support at work functions in a more desirable fashion for employees who take a heartfelt, deep acting approach. Despite managers’ strenuous efforts, it may be difficult to change surface actors’ work attitude and behavior overnight. Good HR practices begin with hiring the right people. The literature on emotional labor describes the personality profile of deep actors. Long-standing positive personality traits, such as extraversion and agreeableness, and newly-risen emotional intelligence are shown to be associated with deep acting behavior (Austin et al., 2008; Lee and Ok, 2012). During the selection process service companies with high levels of guest contacts, should adopt fine-tuned personality tests along with popularly used behavioral questions in order to increase the likelihood of recruiting the best fit candidates.

Finally, our study contributes to an understanding of customer service management in the context of the airline industry by investigating the dynamic relationship between flight attendants’ emotional labor and their job performance. The relationship between flight attendants’ emotional labor and the three types of perceived support reminds airline practitioners of the importance of a more systematic and delicate management of flight attendants’ emotional labor at both an individual (supervisor and coworker support) and the organizational level (organizational support). In other words, airline companies should provide different types of workplace support to enhance job performance, considering how flight attendants use emotional regulation strategies (deep or surface acting) in response to customers’ various demands.

Limitations and future researchThis study is not free of limitations. First, because all the participants came from only one airline, the generalization of the findings is limited. Future research using other hospitality or service segments is recommended to validate the results of this study. In addition, the setting of this study is South Korea where collectivism is embedded in daily life. In this culture, it is a feasible scenario that coworker support is formed more easily, thereby playing a more prominent role in the workplace. In the future, comparative research with contact employees from more individualistic cultures may bring additional, insightful information on the role of different workplace social support.

Job performance was the sole dependent variable in this study although the quality of performance data should receive some credit. Official performance ratings, not self-reported, are difficult to obtain and reduce the potential problem of inflated relationships among study variables. The reason why the results of our study supported only two of the six hypotheses may partially be due to different outcome variables for the different types of perceived support. For instance, because most flight attendants have greater daily contact with supervisors or coworkers in the aircraft cabin than upper level managers in the company, they are more likely to perceive direct cares and support from supervisors and coworkers than the organization itself. Thus, perceived supervisor or coworker support may have more links to employees’ performance. In addition, future research may investigate the moderating hypothesis of workplace social support in an emotional labor context using a more extensive list of outcome variables, such as job satisfaction/burnout (individual well-being), and turnover intentions/withdrawal behavior (organizational well-being), to enhance the current findings. At the same time, because of the prevalence of emotional labor in hospitality businesses, it is critical to continue to look for other potential moderators. For example, friends and family, non-work based support sources, were omitted in this study and may merit examination in the future.

Lastly, it is recommended to consider support measures with more specificity added (e.g., positive vs. negative and job-related vs. non-job related communications with supportive others). Incorporating more specific types of questions within each source of support can further advance our understanding of the role of each support, and as argued by some researchers (Fenlason and Beehr, 1994; McIntosh, 1991), may clarify the result of reverse moderation effect on the relationship between surface acting and job performance noted in this study.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2013S1A5A2A03045125).