Nonprofit organizations (NPOs) confront competitive pressures derived from complex economic and societal challenges. Their capacity to fulfil their mission increasingly depends on developing successful alliances with key external and internal stakeholders, including cooperative interorganizational relationships. In this context, the aim of this research is to analyze: (1) to which extent business-nonprofit partnerships (BNPPs) foster the development of an internal marketing approach by NPOs; (2) the impact of this approach to human resource management on nonprofit performance; and (3) the possible moderating effect of the funding strategy of the nonprofit. This empirical research, based on a survey to a representative sample of Spanish NPOs, shows that cooperative relationships between nonprofit and business organizations are closely associated with a process of knowledge transfer, resulting in improved nonprofit performance; although these positive effects depend on the capacity of NPOs to generate income from commercial sources.

The development of cooperative relationships with internal and external stakeholders, including alliances with other organizations, is critical for nonprofits (NPOs) to ensure mission accomplishment and long-term survival (Wellens and Jegers, 2014). Whereas cooperative relationships with corporate and institutional donors are key to generate private charitable contributions, both business partners and the personnel of nonprofit organizations become strategic allies if the capacity of NPOs to generate income from commercial activities needs to be enhanced.

First, cooperative interorganizational relationships, and especially cross-sector partnerships – i.e. collaborative alliances among businesses, governments, and NPOs that address social causes, have become a significant trend during recent years (Selsky and Parker, 2005). The development of successful business-nonprofit partnerships (BNPPs), in particular, is vital from both the nonprofit and the business perspective. The proliferation of NPOs, combined with economic hardship, is forcing nonprofits not only to compete for shrinking traditional sources – e.g. government grants, but also to develop new resources from the market to ensure long-term survival and to scale their operations in face of rising societal demands (Never, 2011). From the business side, interest in these partnerships has increased in the context of the evolution of corporate social responsibility (CSR) towards the so-called “CR Innovation” paradigm (Halme and Laurila, 2009).

Secondly, most NPOs are service organizations that depend on their personnel's professional skills, service attitude, and motivation in order to provide a satisfactory service to their beneficiaries. As NPOs rely upon a mix of paid and unpaid personnel, both employees and volunteers represent key stakeholders. Their relevance has translated into substantial research on the “internal marketing” approach to human resources management (HRM), showing its positive effects on job satisfaction, commitment to the organization and loyalty of the NPO personnel (Bennett and Barkensjo, 2005; Borzaga and Tortia, 2006; Hume and Hume, 2015). Adoption of this marketing approach originating from the for-profit sector has resulted in enhanced professionalization of HRM in nonprofits (Rodriguez and Sams, 2009).

Previous studies about the topic of BNPPs are mainly conceptual in nature or based on case studies (for an overview see Austin and Seitanidi, 2012a,b). In particular, we lack robust, quantitative studies that integrate the topics of BNPPs and professionalization of NPOs through the development of an internal marketing strategy. Therefore, the first objective of this research is to evaluate the extent to which BNPPs foster a process of knowledge transfer from the firm to the nonprofit organization, encouraging professionalization of the latter through the development of an internal marketing strategy, and ultimately improving nonprofit performance.

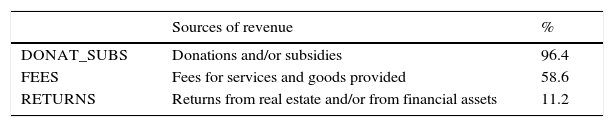

However, these potential positive associations may depend on different factors, most notably the funding strategy of the nonprofit. NPOs can resort to a variety of potential sources of revenue (Andreasen, 2012; Fischer et al., 2011). These include public and private donations and subsidies; fees for services and goods (income earned from commercial activities); and returns from real estate or financial assets. Revenue diversification is generally seen as a necessary strategy to effectively support nonprofit missions in an increasingly challenging resource environment (Carroll and Stater, 2009; Fischer et al., 2011). In scenarios where NPOs undertake commercial activities, the improvement of their internal capabilities will be particularly important to enhance performance, and parallel to this, also the role to be played by external partners in resource development. As anticipated by Dees (1998), “nonprofits exploring commercialization can form alliances with for-profit companies to provide complementary skills and training in business methods”. Consequently, a second goal of this research is to determine how the funding strategy of the NPO moderates the link between cooperative relationships with businesses, internal marketing and performance.

To summarize, by combining these three closely related topics – i.e. BNPPs, professionalization, and revenue diversification, the research attempts to offer a threefold contribution to the literature on cooperative interorganizational relationships, with potential implications for both nonprofit and business partners. First, previous studies have noted that “nonprofits have embraced collaboration with business as an important mode for the generation of value required for successfully meeting their missions” (Austin and Seitanidi, 2012a,b, 734). We provide insights regarding how this process occurs, by means of a positive association between partnering with a firm and the development of internal HRM capabilities. Secondly, the impact of internal marketing programmes on NPO performance is analyzed. This potential effect is especially interesting, since a greater degree of professionalization is increasingly demanded in support functions in NPOs (Hurrell et al., 2011). And thirdly, we test whether these relationships gain relevance in a context where revenue diversification through the development of commercial activities is becoming an essential strategy for this type of organization.

We structure this work as follows. First, we explain the theoretical background of the research. Secondly, we detail the methodology used to conduct the analysis, based on a survey to a representative sample of Spanish NPOs. Third, we interpret the empirical results. Fourth, we discuss the main conclusions and implications for academics and practitioners.

Conceptual frameworkBusiness-nonprofit partnerships as an antecedent of internal marketing in NPOs“Cross-sector partnering, and in particular collaboration between NPOs and business, has increased significantly and is viewed by academics and practitioners as an inescapable and powerful vehicle for implementing corporate social responsibility (CSR) and for achieving social and economic missions” (Austin and Seitanidi, 2012a, 728). Along those lines, the latest developments of the CSR concept – “CR Innovation” (Halme and Laurila, 2009) and “shared value” (Porter and Kramer, 2011) – involve the creation of business value through enhanced competitiveness, while simultaneously addressing social problems in the communities where firms operate. This dual goal is achieved through the development of new business models and cooperative organizational relationships for solving social and environmental problems, including business-nonprofit partnerships (BNPPs) (Lefroy and Tsarenko, 2014).

A cooperative relationship between a company and a nonprofit can experience different degrees of development, depending on the extent to which relational norms guide the interactions between the partners. Accordingly, different types of business-nonprofit alliances can be distinguished in terms of commitment and value creation (Austin and Seitanidi, 2012a): philanthropic (a charitable transfer of monetary or in-kind resources from a corporate donor to a recipient NPO), transactional (partners exchange more valuable resources through specific activities, e.g. sponsorships, cause-related marketing, or personnel engagements), integrative (partners’ missions, strategies, values, personnel, and activities experience organizational integration, resulting in co-creation of value), and transformational partnerships (partners involve in joint problem solving, decision making, management, learning, and conjoined benefits creation).

Relationship marketing is the framework that has studied to a greater extent factors explaining the development of successful cooperative interorganizational relationships, with a focus on transformational partnerships. This approach has been recently extended to the subfield of stakeholder marketing (Iyer and Bhattacharya, 2011), which considers that the organization's behaviour towards multiple stakeholders can be better understood in the context of relationship marketing (Grinstein and Goldman, 2011). Alliances between firms and NPOs have received particular attention among the various approaches to describing and classifying stakeholders in the relationship marketing literature (Frow and Payne, 2011). It has been demonstrated that they “can be improved by adopting a deeper Relationship Marketing approach” (Barroso et al., 2014; 199). The demand “to adopt principle-based stakeholder marketing” has been further argued for the public sector (Mish and Scammon, 2010, 12), given the need for a double (Fairfax, 2004) and triple bottom line (Slaper and Hall, 2011) approach in the context of the trend to outsource social services from public institutions to NPOs.

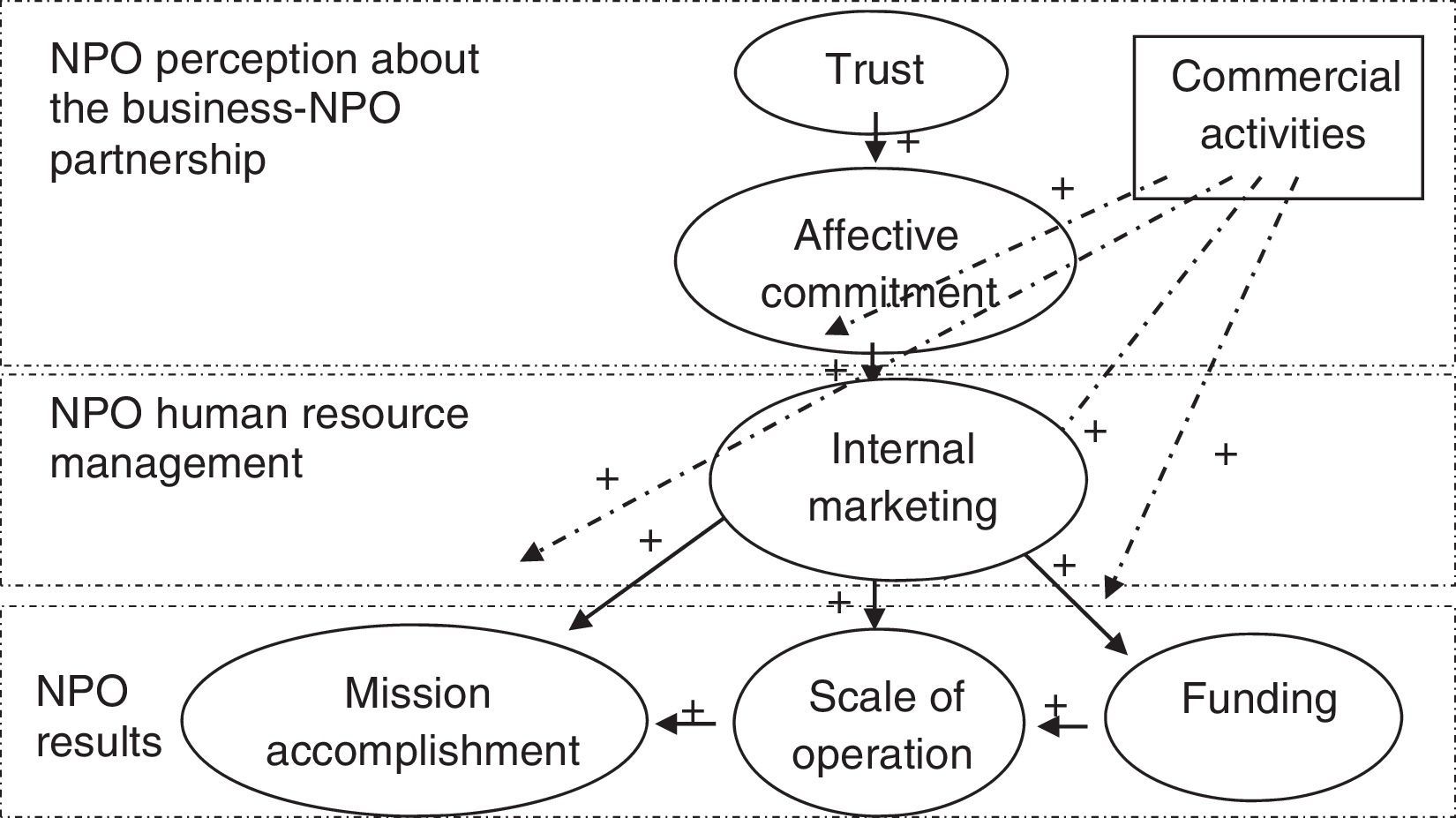

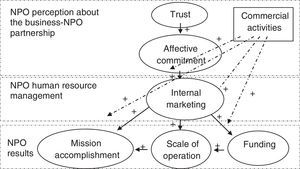

Relationship marketing points to trust and commitment as the key dimensions that explain the success of cooperative interorganizational relationships (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). The crucial role of trust in partnership success has been highlighted by BNPP research, noting that “[t]rusting relationships are often depicted as the essence of collaboration. Paradoxically, they are both the lubricant and the glue—that is, they facilitate the work of collaboration and they hold the collaboration together” (Bryson et al., 2006: 47–48). In its turn, commitment implies that one partner believes the relationship is “so important as to warrant maximum efforts at maintaining it” (Morgan and Hunt, 1994: 23). Most researchers agree that affective commitment – i.e. a type of commitment based on an affective predisposition to maintain the relationship because people in the organization develop emotional bonds with the partner, often as a result of identification with the partner's values – is the most influential factor towards maintaining mutually beneficial relationships. Research on BNPPs has further emphasized the importance of affective bonds for partnership's success (Berger et al., 2006). Moreover, relationship marketing literature widely acknowledges that trust is the major determinant of affective commitment (Palmatier et al., 2006). Therefore, we posit:Hypothesis 1 Nonprofit trust in the firm's behaviour is positively associated with nonprofit affective commitment to the partnership.

Close cooperative interorganizational relationships can give rise to a bilateral process of knowledge transfer and capability building (Austin and Seitanidi, 2012a; Bennett et al., 2008). This possibility is especially relevant for NPOs. According to previous nonprofit literature, in order for NPOs to successfully address current management challenges, a greater degree of professionalization is needed in functions such as administration, finance, ICT, public relations/media, marketing, and human resources (Hurrell et al., 2011). Specifically, our research focuses on professionalization resulting from the implementation of an “internal marketing” approach to Human Resources Management (HRM) in NPOs. HRM represents a critical function in nonprofit organizations because, as service providers, they must maintain personal contacts with their core external stakeholders. Personnel play a decisive role in this process, encouraging NPOs to consider their employees and volunteers as real “internal customers”. Nonprofits should develop policies attempted to obtain information about the expectations and needs of their personnel, in order to improve their satisfaction, skills and service attitude. “Internal marketing” has precisely emerged as an effective approach for HRM in NPOs in this context (Bennett and Barkensjo, 2005). Generally, an internal marketing strategy comprises three main dimensions (Gounaris, 2006): internal market intelligence generation (e.g., collecting information about specific segments of personnel), internal intelligence dissemination (communication between supervisors and personnel), and responses to internal intelligence (e.g., designing jobs or training programmes that meet personnel needs).

As already mentioned, one of the distinctive characteristics of HRM in nonprofits is that, different from for-profit organizations, they often involve both paid staff and unpaid volunteers. Intense competition within and across sectors is forcing NPOs to boost their professionalization by increasing the number of paid employees and improving the competences and skills of all their personnel, paid or unpaid. It is important to note that professionalization does not mean that volunteers become less important, but rather that they tend to be managed in a more formalized way. In fact, competitive pressures are forcing employees and volunteers to coexist in many NPOs, generating tensions and conflicts between both groups (Kreutzer and Jäger, 2011). Elements such as communication, training, clear objectives and trust, are key in order to address these possible tensions (Kreutzer and Jäger, 2011). As a consequence, the development of an internal marketing approach becomes even more necessary (Hume and Hume, 2015). Furthermore, this HRM approach plays a crucial role in volunteer motivation. The associational advantages from feeling connected to others, the perceived importance of volunteer work, the perceived support provided by the nonprofit organization, and the satisfaction and identification with its values are critical sources of motivation and commitment for volunteers (Borzaga and Tortia, 2006; Boezeman and Ellemers, 2008).

Given that internal marketing is a central capability for NPOs, identifying its potential drivers represents a relevant issue. Successful cooperative interorganizational relationships might constitute one of these facilitators. According to Seitanidi and Crane (2009), partnership institutionalization produces affective engagement between partners, as members develop close personal bonds. Austin (2000) also points to personal connections and relationships as drivers of knowledge transfer, as “the extent to which collaborators’ respective resources and core competencies can be accessed and deployed for strategic value depends on the quality and closeness of the partners’ relationship” (Austin, 2000: 85). In the specific context of BNPPs, Bennett et al. (2008) identify the factors that encourage and/or impede effective knowledge transfer between organizations; among them credibility of the source (the extent to which it is perceived as expert, reputable and trustworthy). Therefore, if a nonprofit organization trusts and emotionally engages with a firm, it will be more predisposed to adopt business tools from the for-profit world such as internal marketing strategies. Thus, we expect that,Hypothesis 2 Nonprofit commitment to the partnership is positively associated with its development of an internal marketing approach.

The resource-based view (RBV) of the firm posits that the development of superior internal capabilities helps organizations improve their performance (Barney, 1991). Under this theoretical framework, and given that internal marketing is a critical competence for NPOs, we expect that the enhancement of HRM capabilities positively affects nonprofit performance.

Measuring nonprofit performance is a complex task (Moxham, 2014). The ultimate performance indicator in a nonprofit organization is the extent to which its mission is accomplished (McDonald, 2007). However, this final goal depends on multiple factors, including intermediate performance measures. Scholars have proposed internal and external criteria (Sowa et al., 2004), efficiency and effectiveness measures (LeRoux and Wright, 2010), and objective and perceptual indicators (Sowa et al., 2004). We have taken into consideration the aforementioned challenges faced by NPOs in terms of competitive pressures, scarcer resources, and the need to increase the scale of their operations. Accordingly, we have included in our model two related output indicators, the volume of funding (funding) and the scale of operations (number of activities developed and/or number of beneficiaries reached by its programmes). We also measure the extent to which the nonprofit estimates it has accomplished its mission and satisfied the expectations of beneficiaries and donors, as a proxy of its ultimate performance indicator, i.e. mission accomplishment (Sanzo et al., 2015a).

Internal marketing increases personnel satisfaction, reduces turnover, and improves service orientation and alignment with organizational objectives (Bennett and Barkensjo, 2005). Therefore, under this approach, employees and volunteers will be more willing and prepared to undertake a greater number of fundraising activities, and to expand the number of activities and programmes of the nonprofit and/or provide its services to more beneficiaries. Moreover, an internal marketing is a socially responsible approach to HRM. The organization meets its responsibility for its impacts on its personnel through a strategy that is implemented in close collaboration with affected stakeholders. Thus, we expect internal marketing to directly and positively affect the degree to which the NPO accomplishes its socially valued goals (mission accomplishment). Consequently,Hypothesis 3 Development of an internal marketing approach by a nonprofit is positively associated with its (a) volume of funding, (b) scale of operations (number of activities developed and/or beneficiaries reached), and (c) mission accomplishment.

Previous nonprofit management research (Chen and Hsu, 2013; Modi and Mishra, 2010; Shoham et al., 2006; Vázquez et al., 2002) shows that greater financial resources help the NPO enlarge the scale of its operations, and this factor, in its turn, contributes to the improvement of the perceptions about mission accomplishment. So, we propose two additional hypotheses that show the connections between the proposed performance indicators:Hypothesis 4a Nonprofit funding is positively associated with the scale of its operations. The scale of nonprofit operations is positively associated with perceptions that organizational mission is accomplished.

The potential transfer of know-how from the firm to the NPO might depend on other factors than can boost or alternatively hinder the process (Rathi et al., 2014). For instance, Sanzo et al. (2015b) show how that this knowledge transfer depends on the type of contribution that the firm brings to the partnership: it is stronger when the partnership is based on not-only-monetary (cash) contributions; e.g., in-kind gifts, infrastructures/equipment or corporate employee volunteer programmes. Along those lines, there has long been a consensus that the type of funding strategy of the NPO can play a relevant role in its willingness to adopt management and marketing tools from the for-profit world. Traditionally, “the difference between predominant public sector funding and majority private sector funding emerges as the most important distinction to understand how organizations differ” (Anheier et al., 1997: 212). However, the key distinction is nowadays between NPOs that depend basically on private donations and public grants (contributed income), and those that obtain their income (or at least most of it) from commercial sources such as the sale of goods or charging fees for services (earned income).

At the time when NPOs developed their activities in a context of prosperity, it seemed more important to focus on securing and managing contributions from public and private donors; rather than implementing a proactive and systematic strategy to generate earned income (Macedo and Pinho, 2006). However, the recent economic crisis has produced a drastic reduction of traditional governmental support, coupled with a simultaneous increase in demand for the services provided by NPOs (Never, 2011). Furthermore, it is likely that the aftermath of the crisis (for example in the South of Europe) will significantly impact corporate donations. Consequently, the development of commercial activities as a core or supplementary source of funding is becoming critical to ensure NPO survival and mission accomplishment (Gras and Mendoza-Abarca, 2014). According to Dees (1998), “faced with rising costs, more competition for fewer donations and grants, and increased rivalry from for-profit companies entering the social sector, nonprofits are turning to the for-profit world to leverage or replace their traditional sources of funding… (they) look to commercial funding in the belief that market-based revenues can be easier to grow and more resilient than philanthropic funding” (5–6).

Therefore, implementing this type of funding strategy reflects a proactive non-profit marketing orientation strategy, as Wymer et al. (2015) proposed. We expect this circumstance to reinforce the predisposition of NPOs to adopt business tools and strategies, including an internal marketing approach, also seen as one of the key dimensions of a real market orientation (Akingbola, 2013; Borzaga and Tortia, 2006; Rodriguez and Sams, 2009). Furthermore, service research stresses the fact that personnel motivation, commitment, and coordination are essential for the success of any commercial activity. Thus, it is probable that the intensity of the effect of internal marketing on the nonprofit performance indicators will be greater when the organization is involved in generating earned income. Consequently, we posit that:Hypothesis 5 The positive associations between (a) affective commitment to the partnership and internal marketing, and (2) internal marketing and nonprofit performance, will be stronger if the NPO obtains funds from commercial activities (fees for goods and/or services).

The conceptual model is depicted in Fig. 1.

MethodologyData collection and sample descriptionTo test the conceptual model we focus on foundations as a distinct (Hopt et al., 2006) and fast-growing type of NPO in Europe (European Foundation Centre, 2013). Foundations are non-member nonprofits, and this key feature clearly differentiates them from member organizations such as associations, cooperatives and other organizations of the social economy or the third sector (Hopt et al., 2006). It is estimated that there are about 110,000 foundations in Europe, spending a total of between 83 and 150 billion euros annually on their projects and programmes, and providing employment to up to one million Europeans (European Foundation Centre, 2013).

We surveyed a sample of 525 NPOs, randomly selected from the global census of 9050 Spanish foundations identified by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Analysis of Foundations (INAEF). In Spain, where a “foundation” is one of the two legal formulas available for organizations to incorporate as non-profit from a tax perspective together with associations, non-member nonprofits are estimated to account for approximately half of the nonprofit sector (Rey-García and Álvarez-González, 2011). The fact that this country has a highly institutionalized foundation sector, and also one of the largest numbers of registered public-benefit foundations in the European Union, further explains why analyzing these NPOs represents an interesting case study.

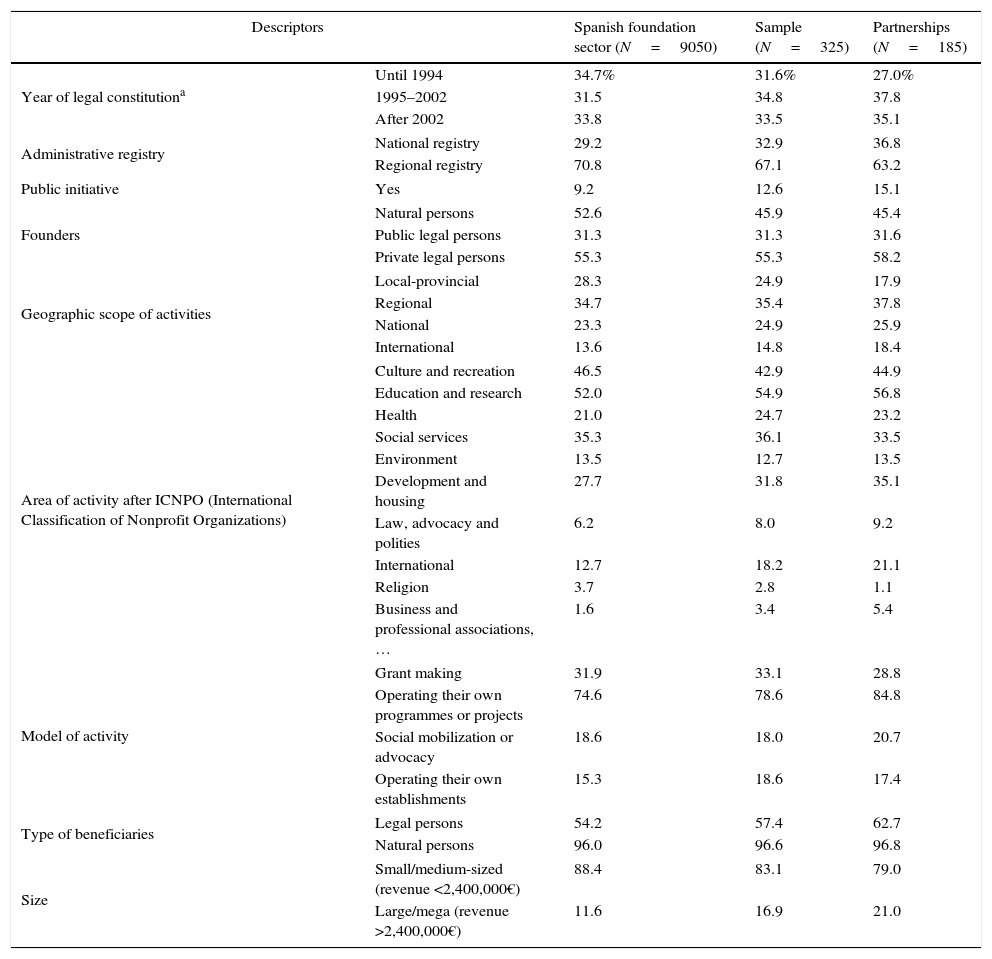

An e-mailed questionnaire was completed by the person in charge of daily decision-making in the organization. We asked each respondent to indicate whether its NPO had collaborated at any time during the past three years with a business in order to achieve its social benefit mission. If they answered in the affirmative, we asked them to indicate their level of agreement with a series of statements about the characteristics of the relationship, their internal marketing policies and the performance of the NPO. We obtained 325 valid questionnaires (sample error=±5.34%; 95% confidence level). Of the 325 NPOs, 185 indicated that they maintained or had maintained a partnership with a firm (Table 1).

Sample description.

| Descriptors | Spanish foundation sector (N=9050) | Sample (N=325) | Partnerships (N=185) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of legal constitutiona | Until 1994 | 34.7% | 31.6% | 27.0% |

| 1995–2002 | 31.5 | 34.8 | 37.8 | |

| After 2002 | 33.8 | 33.5 | 35.1 | |

| Administrative registry | National registry | 29.2 | 32.9 | 36.8 |

| Regional registry | 70.8 | 67.1 | 63.2 | |

| Public initiative | Yes | 9.2 | 12.6 | 15.1 |

| Founders | Natural persons | 52.6 | 45.9 | 45.4 |

| Public legal persons | 31.3 | 31.3 | 31.6 | |

| Private legal persons | 55.3 | 55.3 | 58.2 | |

| Geographic scope of activities | Local-provincial | 28.3 | 24.9 | 17.9 |

| Regional | 34.7 | 35.4 | 37.8 | |

| National | 23.3 | 24.9 | 25.9 | |

| International | 13.6 | 14.8 | 18.4 | |

| Area of activity after ICNPO (International Classification of Nonprofit Organizations) | Culture and recreation | 46.5 | 42.9 | 44.9 |

| Education and research | 52.0 | 54.9 | 56.8 | |

| Health | 21.0 | 24.7 | 23.2 | |

| Social services | 35.3 | 36.1 | 33.5 | |

| Environment | 13.5 | 12.7 | 13.5 | |

| Development and housing | 27.7 | 31.8 | 35.1 | |

| Law, advocacy and polities | 6.2 | 8.0 | 9.2 | |

| International | 12.7 | 18.2 | 21.1 | |

| Religion | 3.7 | 2.8 | 1.1 | |

| Business and professional associations,… | 1.6 | 3.4 | 5.4 | |

| Model of activity | Grant making | 31.9 | 33.1 | 28.8 |

| Operating their own programmes or projects | 74.6 | 78.6 | 84.8 | |

| Social mobilization or advocacy | 18.6 | 18.0 | 20.7 | |

| Operating their own establishments | 15.3 | 18.6 | 17.4 | |

| Type of beneficiaries | Legal persons | 54.2 | 57.4 | 62.7 |

| Natural persons | 96.0 | 96.6 | 96.8 | |

| Size | Small/medium-sized (revenue <2,400,000€) | 88.4 | 83.1 | 79.0 |

| Large/mega (revenue >2,400,000€) | 11.6 | 16.9 | 21.0 | |

Because we used data gathered from a survey, we employed several techniques to assess the possible existence of unit nonresponse bias (Armstrong and Overton, 1977; Groves, 2006). First, we compared the profile (e.g. age, geographic scope, type of nonprofit, founders, model and areas of activity, beneficiaries, and size) of our sample of 325 NPOs with the descriptors of the sector as a whole as provided by the INAEF, as this is considered the most reliable external source to characterize the Spanish foundation sector (Table 1). There are no statistically significant differences between both the descriptors of the sample and those of the population. Second, we compared early versus late respondents. The estimation of a two sample (independent) t-test reveals that there are no statistically significant differences between both groups in any of the key constructs of the model. Third, we compared the mean values of the main constructs of the model obtained from the sample of 325 NPOs, with the values derived from a new sample of 50 additional organizations not included in the final sample. Again, the estimation of a t-test shows that there are no statistically significant differences between both groups.

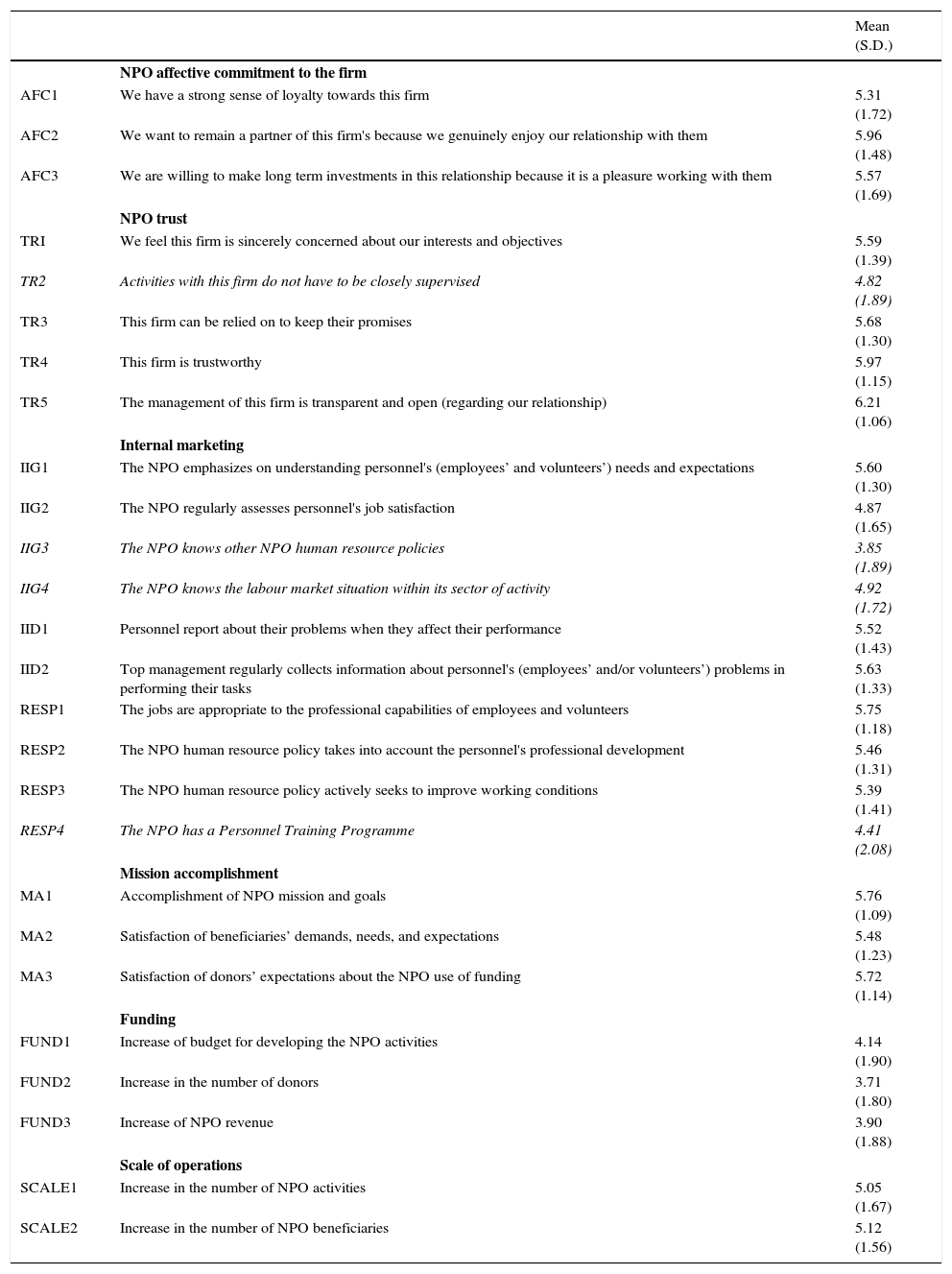

Measuring the model variablesWe used multi-item scales to measure the model constructs (Appendix). The measures employed reflective indicators, and all items used seven-point Likert-type scales, where 1 indicated “completely disagree” and 7 was “completely agree.” The trust and commitment scales are grounded in relationship marketing literature and research on BNPPs (e.g., Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Wetzels et al., 1998; Wymer and Samu, 2003). The items utilized to measure an internal marketing approach come from Gounaris (2006).

With regard to the NPO performance scales, we employed perceptual measures and asked respondents to evaluate the extent to which they believed the objectives established for a set of performance indicators (Vázquez et al., 2002; Modi and Mishra, 2010) had been achieved during the past year. In this case, a value of 1 meant that performance on a particular indicator was significantly below the established objective, whereas 7 indicated that it had significantly exceeded it. We collected information about the organization's sources of revenue from foundation registries.

In order to evaluate the possible magnitude of the common method variance, we performed Harman's single-factor test. This test shows that: (1) an underlying structure of five factors emerges from the factorial analysis, and (2) the main factor comprises 29.83% of total variance, so this type of bias is not a problem in this research. The fact that the moderating variable used in this study was collected from secondary sources also contributes to reduce this potential bias.

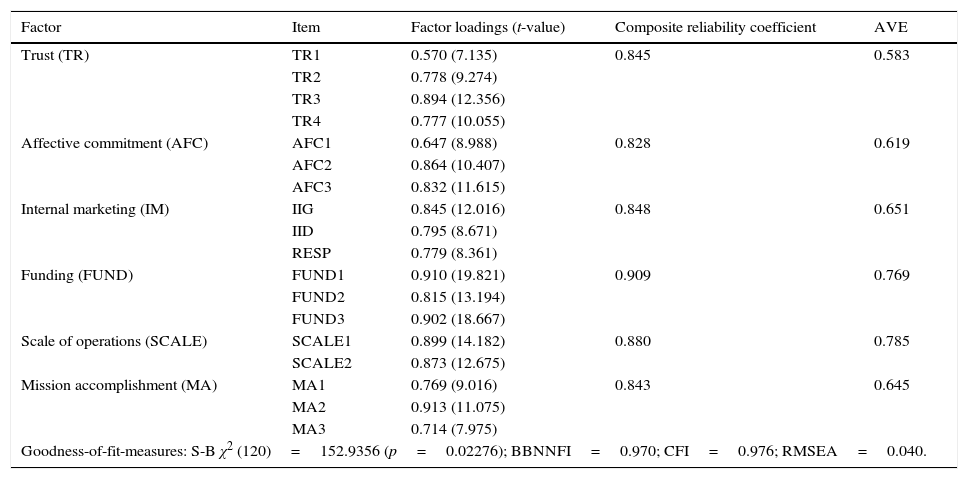

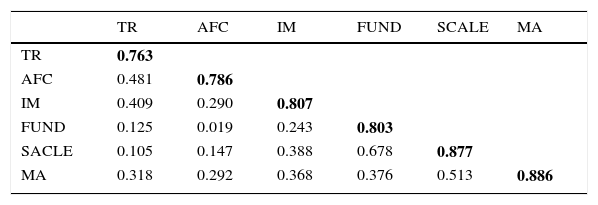

ResultsScale reliability and validityA confirmatory factor analysis (Tables 2 and 3), using EQS 6.2 for Windows, supports the reliability and validity of the model scales (Gerbing and Anderson, 1988; Steenkamp and Trip, 1991). We evaluated reliability using the composite reliability coefficient, which exceeded the recommended value of .7. To assess convergent validity, we confirmed that the standardized parameters were significant and greater than .5. Furthermore, we calculated the average variance extracted (AVE), always greater than .5. In order to evaluate discriminant validity, we compared the AVE of each construct and the shared variance between each pair of constructs; the former always surpassed the latter. The internal marketing scale was multidimensional. Because the dimensions of this construct exhibit convergent validity, we added the individual scores to obtain a global (mean) evaluation of each dimension. We then used the three-item internal marketing factor to estimate the full structural equation model.

Reliability and validity of the model's scales.

| Factor | Item | Factor loadings (t-value) | Composite reliability coefficient | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust (TR) | TR1 | 0.570 (7.135) | 0.845 | 0.583 |

| TR2 | 0.778 (9.274) | |||

| TR3 | 0.894 (12.356) | |||

| TR4 | 0.777 (10.055) | |||

| Affective commitment (AFC) | AFC1 | 0.647 (8.988) | 0.828 | 0.619 |

| AFC2 | 0.864 (10.407) | |||

| AFC3 | 0.832 (11.615) | |||

| Internal marketing (IM) | IIG | 0.845 (12.016) | 0.848 | 0.651 |

| IID | 0.795 (8.671) | |||

| RESP | 0.779 (8.361) | |||

| Funding (FUND) | FUND1 | 0.910 (19.821) | 0.909 | 0.769 |

| FUND2 | 0.815 (13.194) | |||

| FUND3 | 0.902 (18.667) | |||

| Scale of operations (SCALE) | SCALE1 | 0.899 (14.182) | 0.880 | 0.785 |

| SCALE2 | 0.873 (12.675) | |||

| Mission accomplishment (MA) | MA1 | 0.769 (9.016) | 0.843 | 0.645 |

| MA2 | 0.913 (11.075) | |||

| MA3 | 0.714 (7.975) | |||

| Goodness-of-fit-measures: S-B χ2 (120)=152.9356 (p=0.02276); BBNNFI=0.970; CFI=0.976; RMSEA=0.040. | ||||

Discriminant validity of the scales.

| TR | AFC | IM | FUND | SCALE | MA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR | 0.763 | |||||

| AFC | 0.481 | 0.786 | ||||

| IM | 0.409 | 0.290 | 0.807 | |||

| FUND | 0.125 | 0.019 | 0.243 | 0.803 | ||

| SACLE | 0.105 | 0.147 | 0.388 | 0.678 | 0.877 | |

| MA | 0.318 | 0.292 | 0.368 | 0.376 | 0.513 | 0.886 |

Note: The values on the diagonal are the square roots of the AVE coefficients of each of the seven constructs considered. The values off the diagonal are the correlations between each pair of constructs.

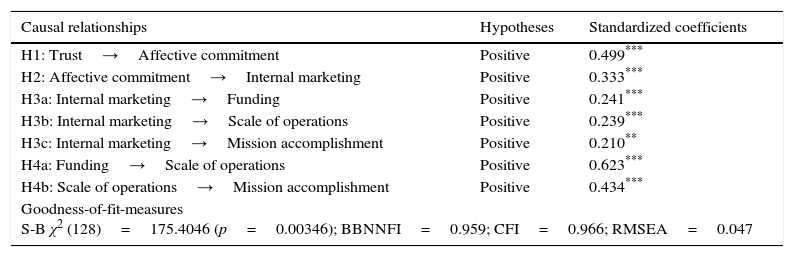

In Table 4 we provide the results of the causal model estimation using SEM with EQS 6.2 for Windows. The goodness-of-fit measures are appropriate. Trust is highly and positively associated with affective commitment (p<.01), supporting H1. We also find support for H2 (p<.01): nonprofit affective engagement with the firm is positively linked to internal marketing, which in turn is positively associated with the achievement of the three performance measures, in support of H3a (p<.01), H3b (p<.01), and H3c (p<.05). Finally, our results support the positive connections between funding and scale of operations (H4a) and scale of operations and mission accomplishment (H4b).

Model estimation results.

| Causal relationships | Hypotheses | Standardized coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| H1: Trust→Affective commitment | Positive | 0.499*** |

| H2: Affective commitment→Internal marketing | Positive | 0.333*** |

| H3a: Internal marketing→Funding | Positive | 0.241*** |

| H3b: Internal marketing→Scale of operations | Positive | 0.239*** |

| H3c: Internal marketing→Mission accomplishment | Positive | 0.210** |

| H4a: Funding→Scale of operations | Positive | 0.623*** |

| H4b: Scale of operations→Mission accomplishment | Positive | 0.434*** |

| Goodness-of-fit-measures S-B χ2 (128)=175.4046 (p=0.00346); BBNNFI=0.959; CFI=0.966; RMSEA=0.047 | ||

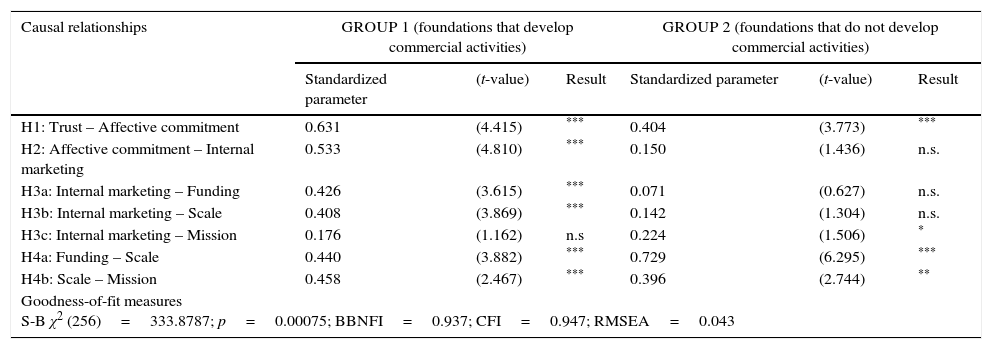

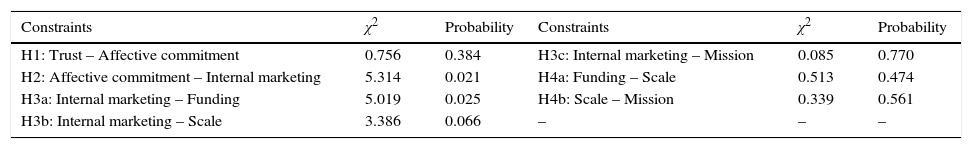

Multi-sample analysis using EQS 6.2 for Windows enabled us to investigate the possible moderating effect of commercial activities as a source of nonprofit funding (Tables 5 and 6). First, we divided the sample into two groups. The first group is comprised of 99 NPOs that obtain funding from the sale of goods or fees for services. The second group refers to 70 NPOs that do not develop commercial activities; instead they obtain their revenues from private donations (from firms, individuals or other NPOs), public grants, or returns from real estate and/or from financial assets. According to Table 6, the strength of the links between (1) affective commitment and internal marketing (p<.05), (2) internal marketing and funding (p<.05), and (3) internal marketing and scale of operations (p<.10), depends on the type of funding strategy of the NPO, supporting H5. These three positive effects are not significant when the NPO does not develop commercial activities (Table 5).

Multisample analysis (Step 1).

| Causal relationships | GROUP 1 (foundations that develop commercial activities) | GROUP 2 (foundations that do not develop commercial activities) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized parameter | (t-value) | Result | Standardized parameter | (t-value) | Result | |

| H1: Trust – Affective commitment | 0.631 | (4.415) | *** | 0.404 | (3.773) | *** |

| H2: Affective commitment – Internal marketing | 0.533 | (4.810) | *** | 0.150 | (1.436) | n.s. |

| H3a: Internal marketing – Funding | 0.426 | (3.615) | *** | 0.071 | (0.627) | n.s. |

| H3b: Internal marketing – Scale | 0.408 | (3.869) | *** | 0.142 | (1.304) | n.s. |

| H3c: Internal marketing – Mission | 0.176 | (1.162) | n.s | 0.224 | (1.506) | * |

| H4a: Funding – Scale | 0.440 | (3.882) | *** | 0.729 | (6.295) | *** |

| H4b: Scale – Mission | 0.458 | (2.467) | *** | 0.396 | (2.744) | ** |

| Goodness-of-fit measures S-B χ2 (256)=333.8787; p=0.00075; BBNFI=0.937; CFI=0.947; RMSEA=0.043 | ||||||

Multisample analysis (Step 2).

| Constraints | χ2 | Probability | Constraints | χ2 | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Trust – Affective commitment | 0.756 | 0.384 | H3c: Internal marketing – Mission | 0.085 | 0.770 |

| H2: Affective commitment – Internal marketing | 5.314 | 0.021 | H4a: Funding – Scale | 0.513 | 0.474 |

| H3a: Internal marketing – Funding | 5.019 | 0.025 | H4b: Scale – Mission | 0.339 | 0.561 |

| H3b: Internal marketing – Scale | 3.386 | 0.066 | – | – | – |

This work has adopted an internal marketing perspective to HRM in nonprofit organizations. In order to address three of the most critical challenges and theoretical debates in current nonprofit management research: cooperative relationships with businesses, nonprofit professionalization, and diversification of revenue sources. The lack of previous empirical works linking cross-sector partnerships, internal capability building, and performance in NPOs reinforces the interest of its results. Thus, this research provides some useful contributions for both academics and practitioners interested in understanding the impact of cross-sector partnerships upon internal resources and capabilities at work in a nonprofit organizational setting; and on the performance of the NPO itself.

The first contribution refers to the positive connection between partnership success and the development of key internal capabilities by the NPO. Stronger degrees of relational development foster learning and knowledge transfer; it is not simply a matter of resources contributed. This transfer depends on the degree of affective engagement. Although monetary support is usually the predominant type of corporate contribution, firms and NPOs should realize that if their strategic goal of the partnership consists of generating added value for society, the alliance should transcend the mere donation of money to imply and develop more specific resources and affective links.

Secondly, our findings suggest that internal marketing policies constitute an outstanding capability for NPOs, as they improve NPO performance. The analysis of the consequences of partnerships from the perspective of the NPO is a significant academic contribution, because previous empirical research has mostly focused on the effects upon business performance. Furthermore, there is still substantial controversy in the nonprofit sector about the desirability of maintaining relationships with firms, adopting professional management styles and/or relying on certain commercial sources of funding (Kreutzer and Jäger, 2011; Reed and Reed, 2009). Our findings confirm some of the advantages of NPO professionalization for mission advancement and for the improvement of certain intermediate performance measures. They also clearly identify partnerships with businesses as a means to encourage this professionalization process.

Third, the access to non-traditional sources of funding (specifically earned income from commercial activities) positively moderates the influence of NPO commitment to the partnership on internal marketing and organizational performance. The intensity of the impact is greater in those NPOs that charge fees for services or sell goods. The development of such market-oriented activities is becoming a key complementary source of revenue for NPOs in an increasingly demanding and competitive environment. Consequently, the roles played by partnerships with firms and by an internal marketing approach to HRM are accordingly gaining in relevance in NPOs, particularly when it comes to addressing complex societal problems under tighter resource constraints.

Managerial implicationsUnder the light of the above-mentioned contributions, the main practical implications concerning the management of cross-sector partnerships and the relevance of adopting tools from the business world are provided, with a particular focus on the perspective of nonprofit practitioners.

First, NPO managers should be receptive to the development of BNPPs with the appropriate companies. Specifically, NPO and business managers should pay particular attention to the climate of trust and commitment in their cooperative interorganizational relationships. In order to encourage them, they should establish an interorganizational team in which members work together to implement the partnership, encourage their physical proximity, ensure the team members’ stability, use formal programmes (e.g., training and seminar sessions) to develop understanding, and encourage temporary personnel mobility to enhance integration of different perspectives. The implementation of all these activities will probably foster communication flows, reduce conflict and risk, and improve the perceived benefits of the collaboration.

Secondly, the development of an internal marketing strategy to manage human resources in NPOs involves a systematic effort to obtain information about the individual needs of employees and volunteers, and to assess their degree of satisfaction. Furthermore, both formal and informal ways of vertical and horizontal communication between employees, volunteers, and their supervisors should be fostered. All this information should be used to design training programmes, positions, and careers that are adjusted to the professional capabilities of the personnel, take into account their professional development, and actively seek to develop better working conditions. These activities can improve personnel's satisfaction and identification with the values and principles endorsed by the NPO and embodied in its socially valued mission.

Third and last, the economic crisis of the beginning of the 90s of the XX century encouraged access to new private donors, as NPOs struggled to face the significant reduction in public funding. Furthermore, recent hardship reveals the need for moving forward and fostering the generation of earned income. In the aftermath of financial crisis, not only public institutions and governments, but also businesses experience difficulties in access to funding. In this context, our research shows that those NPOs that adopt a proactive marketing orientation and build a strategy to generate revenue from commercial activities, are precisely the organizations in which partnering with firms and internal marketing approaches become more significant capabilities towards enhanced competitive advantage.

Limitations and further researchThis work represents a starting point for the empirical study of the enormous potential that partnerships with businesses and marketing capabilities have for improving nonprofit performance and, ultimately, for better addressing complex societal problems through the efficient and effective use of the resources and capabilities of these service organizations. However, the study focuses on Spain, a European country that has been especially affected by the recent economic crisis. Generalization of results to other countries under different institutional settings and financial circumstances should be made with caution.

Furthermore, we have only analyzed the effects of cooperative relationships between nonprofit organizations and firms on the development of capabilities by NPOs. Thus, more research is needed to determine the impact of these alliances on the companies involved, particularly under the internal marketing framework. Another possible line for future research consists of evaluating other moderating variables that could influence the intensity of the effects, for example the type of contributions provided by the firm (monetary vs. non-monetary contributions). Greater research effort is also needed to analyze other outstanding competences, such as the capability of nonprofits to deliver social innovation.

Finally, the contributions of this work suggest some promising orientations for public policies concerning the nonprofit sector. These include the promotion of professionalization and innovation (e.g., by means of the provision of incentives to promote those BNPPs aimed at the development of social innovations, such as entrepreneurial joint ventures between businesses and NPOs), the support for enhanced financial independence through revenue diversification utilizing sustainable commercial sources, and the provision of incentives for more accountable and transparent stakeholder management by NPOs.

The authors acknowledge funding provided by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, as part of its R&D Plan (2009–2011), for the project entitled “Foundations as a key factor of Spanish firms’ corporate social responsibility strategy. Bi-directional analysis of the foundation-firm relationship following a marketing approach” (MICINN-09-ECO2009-11377).

The authors also acknowledge the Spanish Association of Foundations (AEF) for endorsing that research project.

| Mean (S.D.) | ||

|---|---|---|

| NPO affective commitment to the firm | ||

| AFC1 | We have a strong sense of loyalty towards this firm | 5.31 (1.72) |

| AFC2 | We want to remain a partner of this firm's because we genuinely enjoy our relationship with them | 5.96 (1.48) |

| AFC3 | We are willing to make long term investments in this relationship because it is a pleasure working with them | 5.57 (1.69) |

| NPO trust | ||

| TRI | We feel this firm is sincerely concerned about our interests and objectives | 5.59 (1.39) |

| TR2 | Activities with this firm do not have to be closely supervised | 4.82 (1.89) |

| TR3 | This firm can be relied on to keep their promises | 5.68 (1.30) |

| TR4 | This firm is trustworthy | 5.97 (1.15) |

| TR5 | The management of this firm is transparent and open (regarding our relationship) | 6.21 (1.06) |

| Internal marketing | ||

| IIG1 | The NPO emphasizes on understanding personnel's (employees’ and volunteers’) needs and expectations | 5.60 (1.30) |

| IIG2 | The NPO regularly assesses personnel's job satisfaction | 4.87 (1.65) |

| IIG3 | The NPO knows other NPO human resource policies | 3.85 (1.89) |

| IIG4 | The NPO knows the labour market situation within its sector of activity | 4.92 (1.72) |

| IID1 | Personnel report about their problems when they affect their performance | 5.52 (1.43) |

| IID2 | Top management regularly collects information about personnel's (employees’ and/or volunteers’) problems in performing their tasks | 5.63 (1.33) |

| RESP1 | The jobs are appropriate to the professional capabilities of employees and volunteers | 5.75 (1.18) |

| RESP2 | The NPO human resource policy takes into account the personnel's professional development | 5.46 (1.31) |

| RESP3 | The NPO human resource policy actively seeks to improve working conditions | 5.39 (1.41) |

| RESP4 | The NPO has a Personnel Training Programme | 4.41 (2.08) |

| Mission accomplishment | ||

| MA1 | Accomplishment of NPO mission and goals | 5.76 (1.09) |

| MA2 | Satisfaction of beneficiaries’ demands, needs, and expectations | 5.48 (1.23) |

| MA3 | Satisfaction of donors’ expectations about the NPO use of funding | 5.72 (1.14) |

| Funding | ||

| FUND1 | Increase of budget for developing the NPO activities | 4.14 (1.90) |

| FUND2 | Increase in the number of donors | 3.71 (1.80) |

| FUND3 | Increase of NPO revenue | 3.90 (1.88) |

| Scale of operations | ||

| SCALE1 | Increase in the number of NPO activities | 5.05 (1.67) |

| SCALE2 | Increase in the number of NPO beneficiaries | 5.12 (1.56) |

Note: Items in italics were eliminated as a consequence of the scales’ validation process.