Entrepreneurs’ actions and attitudes towards business decisions are fundamental to new ventures. Building on Fauchart and Gruber (2011), which identifies three types of entrepreneurial social identity (Darwinian, communitarian, and missionary), this study analyzes how these identities influence use of effectual and causal logic, while also explaining the effect of the culture of the country in which the entrepreneurship initiative is developed. Based on a survey of 5076 founders who created their own venture, the results support the conclusion that the cultural dimensions defined as avoiding uncertainty, individualism, long term orientation, and distribution of power influence decisions made using effectuation.

New firm creation and the way entrepreneurs work to maintain and grow new firms have been researched extensively (Davidsson, 2004). Two schools of thought focus on how entrepreneurs create a business and the processes by which they do so (Brinckmann et al., 2010). The first school shows that entrepreneurs establish businesses using planned exploration and exploitation of opportunities (Bhave, 1994; Shane and Venkataraman, 2000). The second stresses the emergent nature of entrepreneurship as bricolage (Baker and Nelson, 2005), effectuation (Sarasvathy, 2001), and improvisation (Hmieleski and Corbett, 2006). Among emerging views, effectuation, as described by Sarasvathy (2001, 2008), provides a highly perfected theoretical framework for understanding entrepreneurial processes (Read et al., 2009).

For Sarasvathy (2001), all entrepreneurs begin with three categories of means: who they are—their traits, tastes, and skills; what they know—their education, training, and experience; and whom they know—their social and professional networks (Sarasvathy, 2001). Research demonstrates the importance of prior knowledge and social networks for businesspeople who create new firms and markets (Shane, 2000; Hite and Hesterly, 2001; Wiklund and Shepherd, 2003). The first category—who entrepreneurs are—requires more attention, as it influences how they do things and thus their way of tackling entrepreneurship (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008).

Sarasvathy (2001) argues that entrepreneurs often use a fundamental aspect of their identity to explain their actions and decisions. They state that a person's identity leads him/her to prefer certain processes and ways of living and deciding. This identity may be fictitious or real, freely chosen or socio-culturally constructed (Sarasvathy, 2001).

Culture is an important aspect of identity. Since an individual's personality and behavior are connected to his/her national culture of origin (Berger, 1991), businesspeople from different cultures may have different preferences within the effectuation-causality perspective when creating new business ventures.

The idea that identity (“who I am”) is a mean that Sarasvathy (2001) proposes as fundamental to explaining entrepreneurs’ actions and decisions generates two research questions: Could founders’ different identities be related to use of effectual or causal focus in decision-making? If so, could the culture of the country in which the founder lives have a significant effect on this relationship?

Since national culture influences entrepreneurial spirit significantly (Zahra, 2007), we expect entrepreneurs and their decision-making frameworks to be influenced by the different dimensions composing national culture (Thomas and Mueller, 2000).

Our study aims to contribute to the literature in various ways. First, based on data from current literature, we theorize how different entrepreneurial social identities shape business behavior identified as effectual or causal. Since the entrepreneurial social identity literature lacks empirical data, our study advances knowledge in this field. Second, authors like Perry, Chandler, and Markova (2012) call for studies that develop more in-depth knowledge of the antecedents of effectual and causal behavior. This study advances such knowledge from the issue of the entrepreneur's social identity as a factor shaping entrepreneurial behavior. Third, we provide greater understanding of entrepreneurs as a heterogeneous social group, since the literature stresses the role different social identities (Darwinian, communitarian, missionary) play in analyzing changing motivations, goals, and behavior. Our study also develops more in-depth knowledge of entrepreneurs and their actions.

Our analysis is organized as follows. First, we review the literature on the study variables and justify the hypotheses. Next, we explain the data collection process and validation of the variables, and contrast the research hypotheses. Finally, we present the results obtained and explain the main conclusions, implications for management, limitations, and future lines of research.

HypothesesEffectuation Theory is currently one of the most significant perspectives in entrepreneurship research (Fisher, 2012; Perry et al., 2012). Considering this theoretical framework, effectual logic views the entrepreneurial process as a set of given means that can be combined into a range of possible effects. Within this theory, individual identity is traditionally perceived as one precondition or means that initiates the entrepreneurial process. In entrepreneurship research, identity is a relatively stable prior condition influencing the way business owners organize their preferences and make decisions in the uncertain situation of entrepreneurship (Sarasvathy and Dew, 2005).

According to Effectuation Theory, individuals have a relatively clear, coherent perception of who they are from the start of the entrepreneurial process and act based on this perception (Sarasvathy, 2001).

Breaking with the assumption of preexisting opportunities, markets, etc., Effectuation Theory (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008) focuses on how business owners face the challenge of designing business spirit when they have limited means, the situation is unpredictable, and there are no pre-existing goals. Sarasvathy (2001, 2008) distinguishes between two alternative decision-making logics: effectuation and causation. Causal thinking views rational decision-making as possible and desirable through focus on a predefined plan. Information is complete and a general view of the alternatives/consequences of a successful firm available. Causal logic includes elements of strategic planning, as its goal is to predict an uncertain future (Mintzberg, 1978; Ansoff, 1979). As a decision-making logic, causality combines strict objective orientation (Bird, 1989) with focus on maximizing profit (Friedman, 1953) and competitive analysis (Dutton and Ottensmeyer, 1987). Business owners who apply non-predictive control (effectuation) use different principles (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008; Read and Sarasvathy, 2005; Sarasvathy and Dew, 2005). These principles include creating something new beginning with the resources available (intellectual, human, and social capital), limiting losses to an assumable level, creating prior agreements, and letting plans evolve while developing them. In this theoretical framework, effectual logic (rather than planning and prediction techniques—aspects of causal logic) to increase the robustness of business ventures facing contingencies focuses on control strategies such as flexibility and experimentation to create new products and markets (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008). Effectuation is thus a more proactive and emergent way of dealing with uncertain environments by applying logical reasoning to control the environment. Sarasvathy's study dated on 2008, started from a set of means the individual possesses, of which identity is a fundamental part.

The context of research on business spirit shows growing interest in identity as fundamental to the entrepreneurial process (Down and Warren, 2008; Shepherd and Haynie, 2009; Hoang and Gimeno, 2010). In the context of business initiatives, identity indicates a self with a relatively stable core that determines behavior.

In the entrepreneurial framework, as in other domains, identity is a complex construct whose multidisciplinary roots link it to a series of conceptual meanings and theoretical roles. Understood as internalization and incorporation of socially sustained behavioral expectations, identity can have a significant impact both on how we feel, think and behave (present) and on what we aim to achieve (future) (Obschonka et al., 2012). Individuals with an entrepreneurial identity want and need to distinguish themselves from other members of society (Shepherd and Haynie, 2009), but they also experience the basic psychological need to belong to a group (Tajfel and Turner, 1986). According to Social Identity Theory, people define themselves as members of a group with attributes significantly different from those of another, external group (Tajfel and Turner, 1986). Since new venture creation is an inherently social activity, entrepreneurs shape their behavior based on how others perceive them (Fauchart and Gruber, 2011).

Various studies relate the concept of social identity to use of Effectuation Theory (Nielsen and Lassen, 2012; Alsos et al., 2016; York et al., 2016). For Nielsen and Lassen (2012), this theory has little explicit discussion of how identity unfolds and changes when developing a business. Alsos et al. (2016) study how the entrepreneur's social identity influences his/her behavior in forming new companies. Finally, York et al. (2016) study why and how individuals engage in environmental entrepreneurship. Their findings contribute to the literature on hybrid organizations, social identity, and entrepreneurship on environmental degradation. These studies stress the importance of the entrepreneur's identity in new venture creation but do not consider the effect of the culture of the country where the entrepreneur establishes the business.

Considering these studies and the person's social identity as a cognitive framework for interpreting experiences and options for behavior, social identity explains different entrepreneurial behaviors (Fauchart and Gruber, 2011). Entrepreneurs’ social identity significantly impacts the type of opportunity they exploit (York et al., 2016; Laskovaia et al., 2017; Wry and York, 2017), the strategic decisions they consider appropriate, and the value contribution of their new ventures (Fauchart and Gruber, 2011). The typology of entrepreneurial social identities is based on types identified by Fauchart and Gruber (2011): “Darwinian,” “communitarian,” and “missionary.” The three identities span the logical spectrum of purely founding identities, reflecting their social relationships considering their personal and symbolic interaction with others.

Darwinian entrepreneurs are driven by economic benefits and make decisions mainly to establish strong, profitable new ventures. This strong interest in profits leads them to start business activity by studying the knowledge of technicians and enterprises available in the market to develop a competitive new venture (Fauchart and Gruber, 2011). This orientation to well-defined goals is related to causal decision-making, as it assumes a series of ends it wishes to achieve and bases decision-making on evaluation of expected returns (Alsos et al., 2016).

Communitarian identity resembles the concept of “user entrepreneur” (Shah and Tripsas, 2007), in which users stumble on ideas through their own use and share them with the community. This process involves collective creative activity before creation of business ventures in the community of users (Alsos et al., 2016). Its focus on products and development of businesses due to personal interest is close to effectual conduct, particularly to the principle of starting with means, basing the firm on “who I am” and “what I know” (Sarasvathy and Dew, 2005; Alsos et al., 2016). As this identity is linked strongly to the social group to which founders belong, founders make decisions based on “who they are,” taking their reference group—their social identity—into account.

The missionary identity is closely related to social entrepreneurship (Bacq and Janssen, 2011). Entrepreneurs with a missionary identity hold strong beliefs in their firm as a vehicle for changing some aspects of society (Fauchart and Gruber, 2011). In this assessment, social entrepreneurs make significant contributions to their communities and societies by adopting business models to provide creative solutions to complex social problems (New York University's Stern School, 2005) in ambiguous, uncertain markets. For Dew and Sarasvathy (2007), effectual logic provides useful criteria for action in uncertain markets. Missionary entrepreneurs are identified, however, by strong beliefs in their company as a vehicle to change an aspect of society (Alsos et al., 2016). They see their companies as platforms for pursuing their social goals (Fauchart and Gruber, 2011). Although such goal orientation does not focus on benefit or expected return in the classical sense, the causal principle of making the end a basis for action is close to adoption (Alsos et al., 2016). This identity thus combines the two decision-making logics: effectual logic (faces environments with intense uncertainty) and causal logic (is clearly oriented to achieving a fixed social and/or environmental goal).

Based on the foregoing, Social Identity Theory helps us to understand and explain the heterogeneous processes used to set up a new business initiative. Although different theoretical models can help, Effectuation Theory (Sarasvathy, 2001) is useful to analyze social identity's repercussions for entrepreneurial decision-making.

Based on the foregoing, we propose that Darwinian identity is positively related to causal logic, as it pursues an ultimate goal through focus on planning to identify what benefits the business. Such benefit requires meticulous analysis of product and market characteristics before decision-making. Communitarian identity, in contrast, focuses on business products and development based on personal interest, as does to effectual behavior, inferring utility over other interests. Communitarian identity is thus positively related to effectual logic. Finally, missionary identity emphasizes social goals. Given the complex, uncertain nature of these environments, effectual logic promotes action in complex situations with more intervening agents. Yet it also uses its new venture as a vehicle through which to make decisions to achieve the entrepreneur's pre-established objectives. This behavior may also be closely related to the use of causal logic. Based on the theoretical framework analyzed, we propose the following hypotheses:H1 Darwinian identity is negatively related to effectual logic and positively related to causal logic. Communitarian identity is positively related to effectual logic and negatively related to causal logic. Missionary identity is positively related to both effectual and causal logic.

Analysis of the relationship between a country's culture and business activity is driven by economists (Schumpeter, 1934), sociologists (Weber, 1930), and psychologists (McClelland, 1961), as countries have different levels of business activity. Since business activities are considered as a source of technological innovation (Schumpeter, 1934) and economic growth (Birley, 1987), understanding the influence of national culture on business spirit is of theoretical and practical value. Culture is defined as a set of shared values, beliefs, and expected behaviors (Herbig, 1994; Hofstede, 1980).

Following seminal studies (Shane et al., 1991; Shane, 1993; Davidsson, 1995) and Hayton et al. (2002), the research analyzed here shows three broad streams on national culture and entrepreneurship. The first focuses on the impact of national culture on aggregate measures of entrepreneurship, such as national innovative output or new businesses created. The second studies the association of national culture with the characteristics of individual entrepreneurs. Here, researchers examine values, beliefs, motivations, and cognitions of entrepreneurs across cultures. The third stream explores the impact of national culture on corporate entrepreneurship. The second stream grounds scholarly acceptance that cultural values shape the individual's cognitive schemes, programming consistent behavioral patterns in the cultural context (Liñán and Fernandez-Serrano, 2014; Hofstede, 2003). In Effectuation Theory, entrepreneurial behavior and action are guided by effectual decision making (Sarasvathy and Dew, 2005). The theory is thus based on asserting that individuals make decisions according to their perceptions of the level of uncertainty and predictability in the environment (Sarasvathy, 2001).

Culture, defined as the underlying system of values peculiar to a specific group or society (Mueller and Thomas, 2001), motivates individuals in one society to engage in behaviors that may not be seen in others. Various authors (Busenitz et al., 2000; George and Zahra, 2002; Mueller et al., 2002) view culture as moderating between economic and institutional conditions, and entrepreneurship (Liñán and Chen, 2009).

Based on the study by Laskovaia et al. (2017) we consider four main approaches used in the entrepreneurship literature to operationalize national culture empirically:

- –

Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) Project (House et al., 2004). Investigates the role of 9 cultural dimensions in social life: performance orientation, uncertainty, avoidance, in-group collectivism, power distance, gender egalitarianism, humane orientation, institutional collectivism, future orientation, and assertiveness.

- –

Schwartz's Survey of Values (Schwartz, 1992, 1994, 1999). Assumes 7 value types for intercultural comparison: embeddedness, intellectual autonomy, affective autonomy, hierarchy, mastery, egalitarianism, and harmony.

- –

World Values Survey. Analyzes a large variety of people's values and beliefs on policies, religion, national identity, environment, family, and economic and social life (Inglehart, 1990, 2006).

- –

Hofstede's cultural dimensions’ framework (Hofstede, 1980, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010). An approach composed of 6 main cultural attributes that affect behavioral patterns: individualism/collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity/femininity, long-term/short-term orientation (STO), and indulgence.

The literature debates these approaches considerably. Some scholars stress level-of-analysis confusion, arguing that nation and culture scores cannot be used to characterize individuals (Brewer and Venaik, 2012; Venaik and Brewer, 2013). Tung and Verbeke (2010) have published much analysis of conceptual and methodological issues on Hofstede's oeuvre vs. the GLOBE project's cultural dimensions.

Based on Saleem and Larimo (2017), scholars from various disciplines favor Hofstede's framework because of its clarity and parsimony in measuring culture (Kirkman et al., 2006). Comparisons of these dimensions to other approaches to culture show greater convergence among them, supporting theoretical association with Hofstede's dimensions and justifying their use (Soares et al., 2007). In the 2001 edition of Culture's Consequences, Hofstede documents that cultural dimension scores correlate closely with over 400 societal phenomena and tend not to weaken over time. “[T]he IBM corporation dimension scores have remained as valid in 2010 as they were around 1970, indicating that they describe relatively enduring aspects of these countries societies” (Hofstede et al., 2010, p. 39).

Many definitions of culture exist (Taras et al., 2009; Chanchani and Theivanathampillai, 2002), and they differ by research field (e.g., sociology, anthropology, the humanities). Sociological analysis defines culture as a pattern of shared values, beliefs, and behaviors of a group of people (Hofstede, 1998), since, as stated above, behavior and action are guided by effectual decision making (Sarasvathy and Dew, 2005). Various definitions share these elements. Hofstede (2001) treats culture as “collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” and explains that “mind” stands for thinking, feeling and acting.

Cultural values are also likely to determine “the degree to which a society considers entrepreneurial behaviors, such as risk taking and independent thinking, to be desirable” (Hayton et al., 2002, p. 33). The relationship between identity and behavior has long been a key question in social psychology (Burke and Reitzes, 1981) and has recently entered the field of entrepreneurship (Hoang and Gimeno, 2010; Fauchart and Gruber, 2011; Powell and Baker, 2014; Sieger et al., 2016; Alsos et al., 2016; Kromidha and Robson, 2016). Sieger et al. (2016) propose that the research on identity formation is valuable in improving understanding of how and why cultures differ in their conception of social others, particularly since “the self is shaped, in part, through interaction with groups.” (Triandis, 1989, p. 506). Triandis (1989) argues that the self is shaped by cultural variables, including the complexity of the culture a person lives in, its individualistic or collectivistic nature, and its homogeneity or heterogeneity. We thus assume that national culture influences entrepreneurial social identity.

Cultures can be characterized using distinct dimensions. The literature proposes many sets of classificatory dimensions (e.g., Inglehart and Baker, 2000; House et al., 2002). Extensive use of Hofstede's dimensions in the last three decades in both theoretical and empirical research argues their use as a well-grounded approach to describing culture as used in this article. We analyze five dimensions1 to determine their impact on decisions about effectual and causal logic.

Avoiding uncertaintyHofstede defines avoiding uncertainty as “the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by uncertain or unknown situations” (Hofstede, 2001, p. 161). Business owners in cultures with low propensity to this dimension tend to exploit any relationship based on their close networks. Business owners in cultures with higher propensity to avoid uncertainty are more likely to persist with trust based on established relationships, despite the threat perceived in the environment.

We thus assume that avoiding uncertainty impacts decision-making with effectual logic. A major principle of Effectuation Theory (Sarasvathy, 2001) is “affordable loss,” which focuses on projects where loss in a worst-case scenario is affordable (effectuation) vs. maximization of expected returns (causation) (Chandler et al., 2011). This conclusion leads us to affirm that effectual entrepreneurs try to avoid taking risks in their ventures, whereas causal entrepreneurs calculate the possible risks in advance to measure the expected returns. Hence, this dimension could only influence the effectual decision-making. Based on the foregoing, we formulate the following hypothesis:H4 A culture characterized by avoiding uncertainty intensifies the relationship between the entrepreneur's social identity and the use of effectual logic but does not affect the relationship between the entrepreneur's social identity and the use of causal logic.

Individualism stands for a society in which the ties between individuals are loose: Everyone is expected to look after him/herself and her/his immediate family only. Collectivism stands for a society in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people's lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty” (Hofstede, 2001, p. 225). Countries with low individualism use alliances or associations. In more collectivist cultures (less individualism), knowing the right people is most important, whereas individual capability is most important in cultures that score high for individualism (Hofstede, 2001). Based on Effectuation Theory, the types of means available to ground effectual logic are fundamental to the process. The first type includes the individual's stable abilities and attributes; the second are his/her education, experience, and unique skills; the third is his/her social network (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008). Causal entrepreneurs tend to focus more on competitive analysis, and effectual entrepreneurs more on alliances with the social group/network as means for launching a new venture. Since countries with high collectivism are associated with use of alliances or associations, individualism in a society may influence decisions based on effectual logic but not mediate use of causal logic. We can thus formulate the following hypothesis:H5 A culture characterized by individualism intensifies the relationship between the entrepreneur's social identity and the use of effectual logic but does not affect the relationship between the entrepreneur's social identity and the use of causal logic.

Distribution of power (PDI) is the degree to which individuals accept and expect power in organizations and institutions to be distributed unequally (pluralist vs. elitist). Cultures with high PDI have unequal distribution of power, strong hierarchies, control mechanisms, and emphasis on deferring to and obeying imposition of power (Hofstede, 1980). Busenitz and Lau (1996) argue that high PDI promotes entrepreneurial activity. Mitchell et al. (2000) find that PDI influences arrangement, ability, and behavior cognitions, which in turn affect decisions to start up. As effectual entrepreneurs are guided by their behavior and action (Sarasvathy and Dew, 2005), this cultural dimension may influence effectual decision-making. Entrepreneurs who use causal decision-making seek to carry out a series of planned actions. Their decision-making is not adaptable to environmental circumstances. Based on the foregoing, we propose the following hypothesis:H6 A culture characterized by high PDI intensifies the relationship of the entrepreneur's social identity to the use of effectual logic but does not affect the relationship between the entrepreneur's social identity and the use of causal logic.

A “masculine” society expects men “to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success; women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life” (Hofstede, 1998, p. 6). In high-masculinity cultures, gender roles are more sharply differentiated, showing “a gap between men's-values and women's-values” (Hofstede and McCrae, 2004, p. 64). Gender researchers (Manolova et al., 2002) propose gender influences on entrepreneurs’ motivation in business performance, and growth expectations (Davis and Shaver, 2012). However, the studies analyzed link gender (as variable) but not masculinity or femininity as cultural dimensions to entrepreneurial decision-making (Seuneke and Bock, 2015; Dean and Ford, 2017; Addo, 2017). Gender attributes thus do not influence effectual and causal logic. Based on the foregoing, we propose the following hypothesis:H7 A culture characterized by masculinity does not intensify the relationship between the entrepreneur's social identity and the use of effectual and causal logic.

Long-term orientation [LTO] stands for the fostering of virtues oriented towards future rewards, in particular, perseverance and thrift. Its opposite pole, STO, stands for the fostering of virtues related to the past and present, in particular, respect for tradition, preservation of “face” and fulfilling social obligations” (Hofstede, 2001, p. 359). This dimension may be linked to effectual logic via adaptation to execution, “[t]aking advantage of contingencies instead of avoiding them” (Dew et al., 2009). When individuals seek personal security and stability, they work hard to avoid contingencies; an adaptable individual is more likely to take advantage of contingencies. By this logic, LTO influences entrepreneurs who make decisions based on effectual logic but not those who base decisions on causal logic. We thus propose the following hypothesis:H8 A culture characterized by LTO intensifies the relationship of the entrepreneur's social identity to the use of effectual logic but does not affect the relationship of the entrepreneur's social identity to the use of causal logic.

Drawing on the theoretical position formulated here, we now test whether the processes related to effectuation or causality are intensified by the cultural dimensions analyzed: avoiding uncertainty, individualism, PDI, masculinity, and LTO.

MethodologyThe study data were drawn from the 2013/2014 “Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ Survey” (GUESSS) for (Sieger et al., 2014). Over 1.9 million students globally from 759 universities participated in the edition.2 We used the project's international database, which included 33 countries.3 The survey was completed by 5076 students who had created their own firms. Their average age was 26, 61.3% men and 38.7% women. Most firms operated in advertising, marketing, and design (25.9%); the sector with lowest participation was wholesale and retail commerce (8.1%). Exchange students were omitted to provide impartial estimators of cultural attributes.

Measurement of the study variablesSocial IdentityBased on the scale validated by Sieger et al. (2016), we analyze the entrepreneur's “frame of reference” considering Darwinian (α=0.87), communitarian (α=0.90) and missionary (α=0.92) identity. Since we cannot measure the founder's social identity directly (as it is latent and psychologically abstract), we develop and use a scale (Netemeyer et al., 2003; Sieger et al., 2016).

Effectual and causal logicChandler et al. (2011) ground the measurement scale for effectual logic. They validated the measurements with exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, demonstrating content, predictive and construct validity. Based on their analysis, effectual logic is a formative construct with three second-order reflective dimensions (experimentation (α=0.76), affordable loss (α=0.89), and flexibility (α=0.86)). We advise against including “preliminary agreements” here, as Chandler et al. (2011) find evidence that they are a sub-dimension shared with causal logic.

The measurement scale for causal logic is also based on Chandler et al. (2011). Causal logic is a variable composed of three reflective items (α=0.89) that ask the founder about his/her decisions to design and plan business strategies, research/choose the target market, and analyze competitors, as well as design and plan production and marketing strategies. In this survey, both these questions and those related to entrepreneurial social identity were measured using a multi-item scale. Evaluations were captured using a 7-point Likert scale (1=Strongly disagree, 7=Strongly agree).

Cultural dimensionsFollowing the theoretical framework, we based our analysis on the cultural dimensions defined by Hofstede (2001) to analyze the moderation of country in the relationship between social identities and effectual and causal logic.

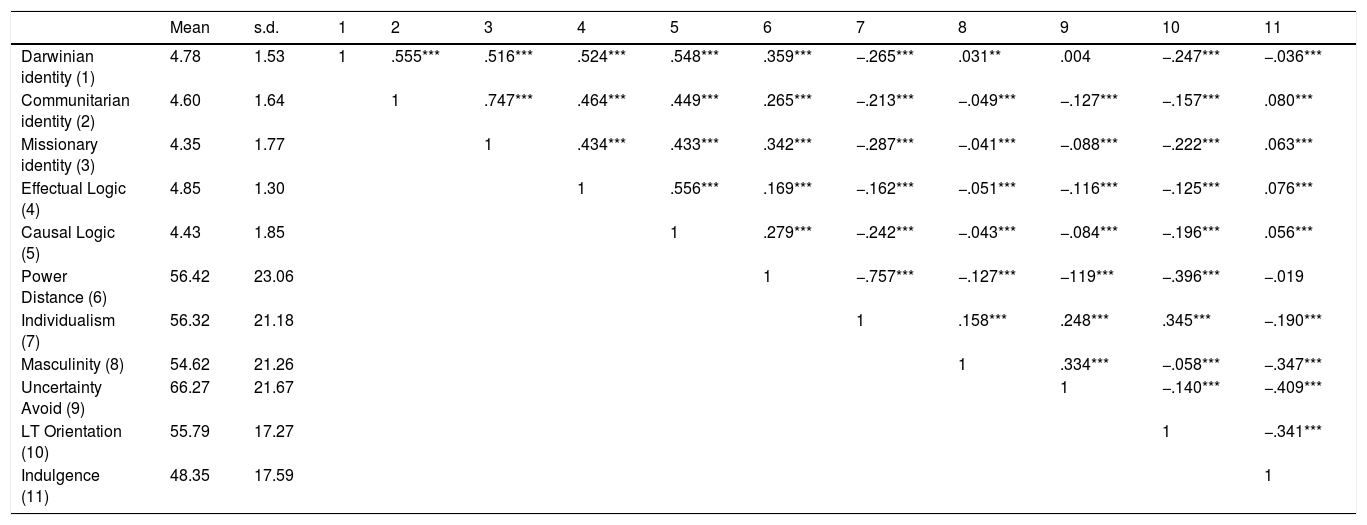

Analysis and resultsTo analyze the results, we focused initially on the data from Table 1, which displays the mean, standard deviation, and correlation of the study variables.

Correlation among the variables analyzed.

| Mean | s.d. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darwinian identity (1) | 4.78 | 1.53 | 1 | .555*** | .516*** | .524*** | .548*** | .359*** | −.265*** | .031** | .004 | −.247*** | −.036*** |

| Communitarian identity (2) | 4.60 | 1.64 | 1 | .747*** | .464*** | .449*** | .265*** | −.213*** | −.049*** | −.127*** | −.157*** | .080*** | |

| Missionary identity (3) | 4.35 | 1.77 | 1 | .434*** | .433*** | .342*** | −.287*** | −.041*** | −.088*** | −.222*** | .063*** | ||

| Effectual Logic (4) | 4.85 | 1.30 | 1 | .556*** | .169*** | −.162*** | −.051*** | −.116*** | −.125*** | .076*** | |||

| Causal Logic (5) | 4.43 | 1.85 | 1 | .279*** | −.242*** | −.043*** | −.084*** | −.196*** | .056*** | ||||

| Power Distance (6) | 56.42 | 23.06 | 1 | −.757*** | −.127*** | −119*** | −.396*** | −.019 | |||||

| Individualism (7) | 56.32 | 21.18 | 1 | .158*** | .248*** | .345*** | −.190*** | ||||||

| Masculinity (8) | 54.62 | 21.26 | 1 | .334*** | −.058*** | −.347*** | |||||||

| Uncertainty Avoid (9) | 66.27 | 21.67 | 1 | −.140*** | −.409*** | ||||||||

| LT Orientation (10) | 55.79 | 17.27 | 1 | −.341*** | |||||||||

| Indulgence (11) | 48.35 | 17.59 | 1 |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

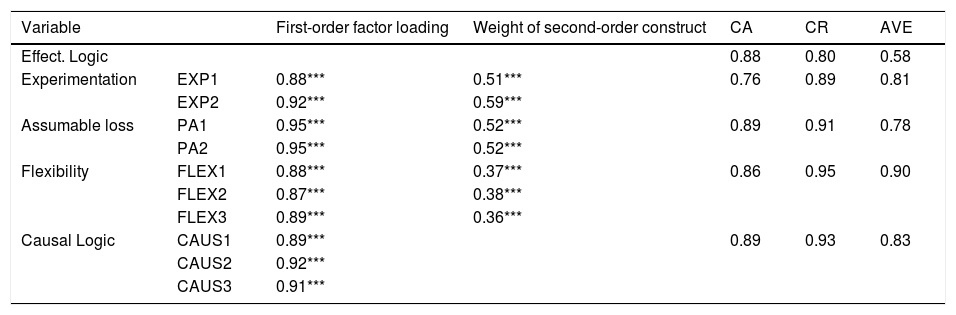

After data collection, we validated the measurement instruments with reliability and dimensionality analysis (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). To evaluate the scales’ initial reliability, we used the Alpha Cronbach, considering 0.7 as the minimum value (Nunnally, 1978). All items exceeded the minimum threshold for this criterion.

To assess the effect of the proposed theoretical model, we adopted the structural equations method, using the partial least squares technique (PLS-SEM) (Fornell and Cha, 1994) with Smart PLS version 3.0 (Ringle et al., 2015). Various qualities of PLS-SEM have led to its increased use in research on topics in management and strategy (Sattler et al., 2010). PLS-SEM is suitable for this study because it lets us use both formative and reflective scales; structural equations models (SEM) based on covariance structures have limitations with formative constructs (Henseler et al., 2009). Our model used social identities in their three formative dimensions as independent variables, as these dimensions together determine a founder's social identity (Sieger et al., 2016); and effectual logic, a formative construct composed of three second-order formative dimensions (experimentation, assumable loss, and flexibility) (Chandler et al., 2011). When the proposed model includes a second-order construct, the appropriate PLS-SEM method is the hierarchical component model, proposed by Wold (cit. Chin et al., 2003).

Our next step is to evaluate validity and reliability of the measurement model, confirming whether the manifest variables measure the different theoretical concepts correctly. We performed this confirmation by analyzing the scale's validity and reliability. To evaluate the items’ individual reliability, we used the indicators’ loadings (λ) on their respective constructs. For Carmines and Zeller (1979), integrating an indicator into a construct requires a loading greater than or equal to 0.7. To test convergent validity of the constructs, we analyzed the Alpha Cronbach (α), Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). Table 2 presents the α and CR values. For all constructs, the values are above the required threshold of 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978; Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2011) and the AVE is above the 0.50 criterion defined by Fornell and Larcker (1981).

Analysis of variables in the measurement model.

| Variable | First-order factor loading | Weight of second-order construct | CA | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect. Logic | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.58 | |||

| Experimentation | EXP1 | 0.88*** | 0.51*** | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.81 |

| EXP2 | 0.92*** | 0.59*** | ||||

| Assumable loss | PA1 | 0.95*** | 0.52*** | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.78 |

| PA2 | 0.95*** | 0.52*** | ||||

| Flexibility | FLEX1 | 0.88*** | 0.37*** | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.90 |

| FLEX2 | 0.87*** | 0.38*** | ||||

| FLEX3 | 0.89*** | 0.36*** | ||||

| Causal Logic | CAUS1 | 0.89*** | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.83 | |

| CAUS2 | 0.92*** | |||||

| CAUS3 | 0.91*** |

Note: CA: Alpha Cronbach α; CR: Composite Reliability; AVE: Average Variance Extracted.

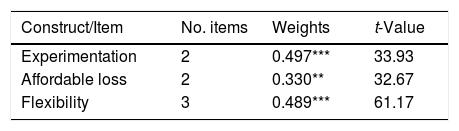

Table 3 presents the weights of the second-order constructs and the associated t-values.

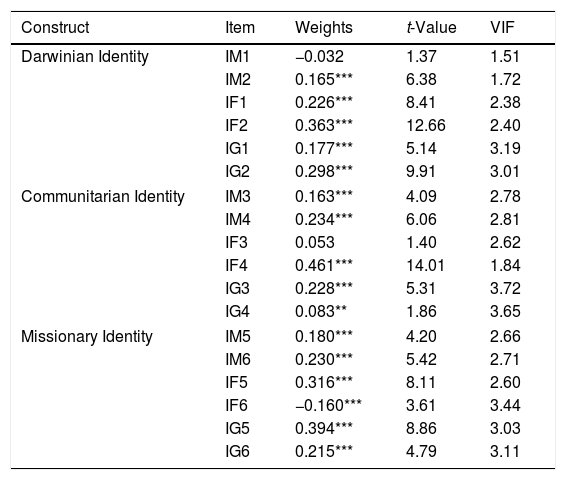

As the independent variables are formative, we proceed to analyze the weights of the items that compose them. Table 4 presents this information.

Weights of formative variables.

| Construct | Item | Weights | t-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darwinian Identity | IM1 | −0.032 | 1.37 | 1.51 |

| IM2 | 0.165*** | 6.38 | 1.72 | |

| IF1 | 0.226*** | 8.41 | 2.38 | |

| IF2 | 0.363*** | 12.66 | 2.40 | |

| IG1 | 0.177*** | 5.14 | 3.19 | |

| IG2 | 0.298*** | 9.91 | 3.01 | |

| Communitarian Identity | IM3 | 0.163*** | 4.09 | 2.78 |

| IM4 | 0.234*** | 6.06 | 2.81 | |

| IF3 | 0.053 | 1.40 | 2.62 | |

| IF4 | 0.461*** | 14.01 | 1.84 | |

| IG3 | 0.228*** | 5.31 | 3.72 | |

| IG4 | 0.083** | 1.86 | 3.65 | |

| Missionary Identity | IM5 | 0.180*** | 4.20 | 2.66 |

| IM6 | 0.230*** | 5.42 | 2.71 | |

| IF5 | 0.316*** | 8.11 | 2.60 | |

| IF6 | −0.160*** | 3.61 | 3.44 | |

| IG5 | 0.394*** | 8.86 | 3.03 | |

| IG6 | 0.215*** | 4.79 | 3.11 | |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; VIF<5 (Hair et al., 2011).

Although some weights are not significant, we believe it is best not to eliminate the items from the model. Since analysis of the weight-loading relationship of these indicators (Hair et al., 2014) shows that their corresponding loading is high (>0.6), eliminating a dimension would alter construction of the scale (Sieger et al., 2016). We therefore believe it is best to preserve them.

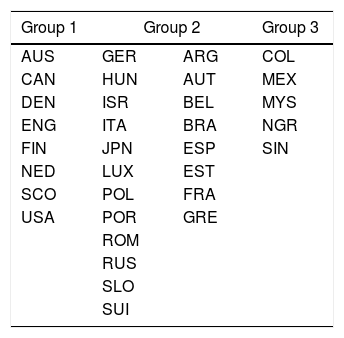

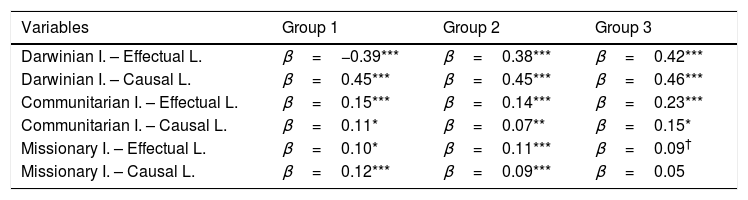

First, we have analyzed the moderating effect of culture in social identities’ influence on causal and effectual logic. We perform cluster analyses by hierarchical conglomerates (Ledesma-Ruiz et al., 2015; Helstrup et al., 2007) and then use “inter-group” grouping. We then use a dendogram graphic to select tree groups of countries (see Table 5).

In the next step, we perform a multi-group analysis using the tool PLS-MGA with a non-parametric focus (Henseler et al., 2009). This information is shown in Table 6.

Multigroup analyses.

| Variables | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Darwinian I. – Effectual L. | β=−0.39*** | β=0.38*** | β=0.42*** |

| Darwinian I. – Causal L. | β=0.45*** | β=0.45*** | β=0.46*** |

| Communitarian I. – Effectual L. | β=0.15*** | β=0.14*** | β=0.23*** |

| Communitarian I. – Causal L. | β=0.11* | β=0.07** | β=0.15* |

| Missionary I. – Effectual L. | β=0.10* | β=0.11*** | β=0.09† |

| Missionary I. – Causal L. | β=0.12*** | β=0.09*** | β=0.05 |

Table 6 shows substantial differences between groups, especially concerning missionary identity. The cultural dimensions analyzed have no significant effect on founders with missionary identity in the countries in Group 3, composed mostly of countries with developing economies, but they do have significant influence in the countries in Groups 1 and 2. The most significant differences between the groups’ average dimensions involve Power Distance, Individualism, LTO and Uncertainty Avoidance.

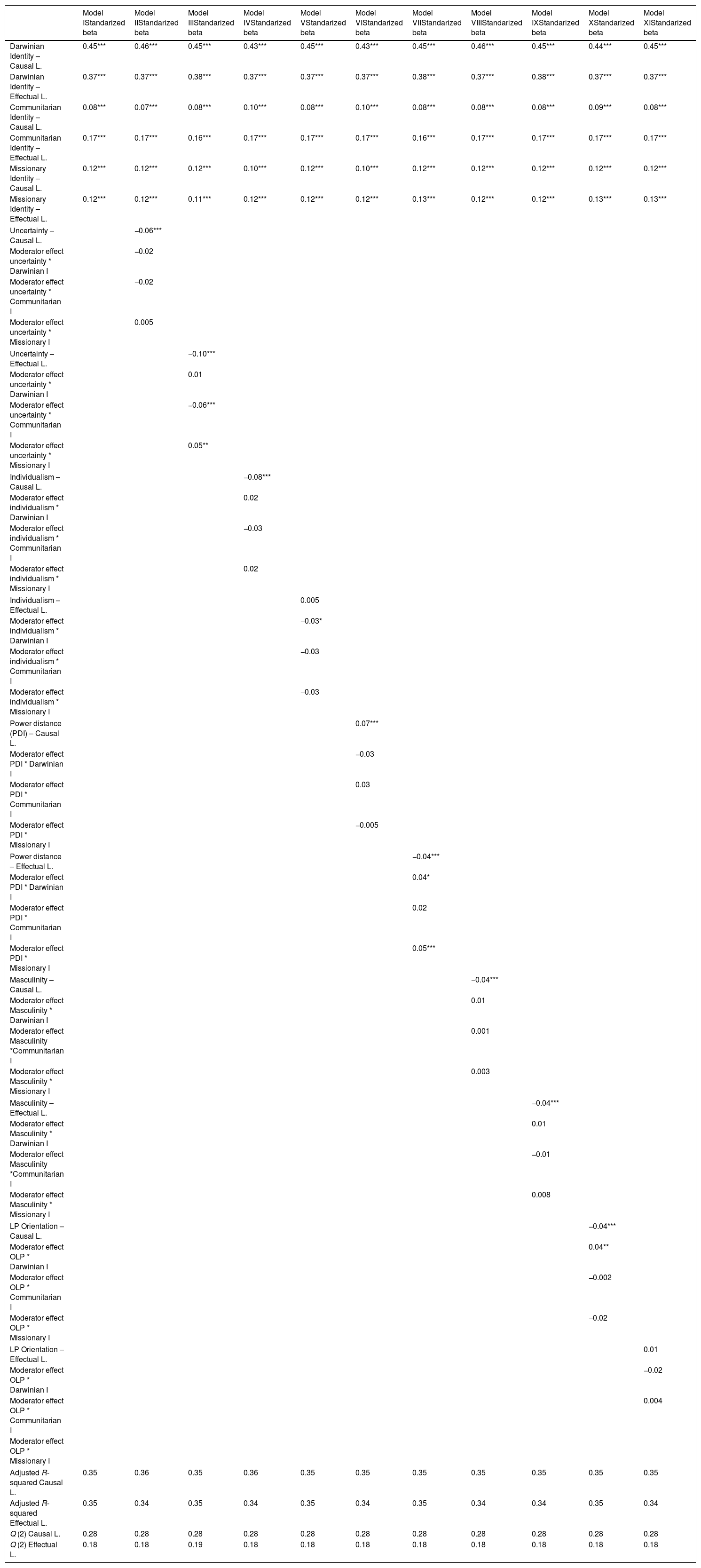

Next, we evaluate the hypothetical model. Since the moderator variable is formative, we evaluate the moderator effect using the “two stage approach” (Chin et al., 2003). Table 7 (below) presents the interaction of the moderator effect of each identity separately.

Results of the moderator effect.

| Model IStandarized beta | Model IIStandarized beta | Model IIIStandarized beta | Model IVStandarized beta | Model VStandarized beta | Model VIStandarized beta | Model VIIStandarized beta | Model VIIIStandarized beta | Model IXStandarized beta | Model XStandarized beta | Model XIStandarized beta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darwinian Identity – Causal L. | 0.45*** | 0.46*** | 0.45*** | 0.43*** | 0.45*** | 0.43*** | 0.45*** | 0.46*** | 0.45*** | 0.44*** | 0.45*** |

| Darwinian Identity – Effectual L. | 0.37*** | 0.37*** | 0.38*** | 0.37*** | 0.37*** | 0.37*** | 0.38*** | 0.37*** | 0.38*** | 0.37*** | 0.37*** |

| Communitarian Identity – Causal L. | 0.08*** | 0.07*** | 0.08*** | 0.10*** | 0.08*** | 0.10*** | 0.08*** | 0.08*** | 0.08*** | 0.09*** | 0.08*** |

| Communitarian Identity – Effectual L. | 0.17*** | 0.17*** | 0.16*** | 0.17*** | 0.17*** | 0.17*** | 0.16*** | 0.17*** | 0.17*** | 0.17*** | 0.17*** |

| Missionary Identity – Causal L. | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.10*** | 0.12*** | 0.10*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** |

| Missionary Identity – Effectual L. | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.11*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.13*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.13*** | 0.13*** |

| Uncertainty – Causal L. | −0.06*** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect uncertainty * Darwinian I | −0.02 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect uncertainty * Communitarian I | −0.02 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect uncertainty * Missionary I | 0.005 | ||||||||||

| Uncertainty – Effectual L. | −0.10*** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect uncertainty * Darwinian I | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect uncertainty * Communitarian I | −0.06*** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect uncertainty * Missionary I | 0.05** | ||||||||||

| Individualism – Causal L. | −0.08*** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect individualism * Darwinian I | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect individualism * Communitarian I | −0.03 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect individualism * Missionary I | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| Individualism – Effectual L. | 0.005 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect individualism * Darwinian I | −0.03* | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect individualism * Communitarian I | −0.03 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect individualism * Missionary I | −0.03 | ||||||||||

| Power distance (PDI) – Causal L. | 0.07*** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect PDI * Darwinian I | −0.03 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect PDI * Communitarian I | 0.03 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect PDI * Missionary I | −0.005 | ||||||||||

| Power distance – Effectual L. | −0.04*** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect PDI * Darwinian I | 0.04* | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect PDI * Communitarian I | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect PDI * Missionary I | 0.05*** | ||||||||||

| Masculinity – Causal L. | −0.04*** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect Masculinity * Darwinian I | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect Masculinity *Communitarian I | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect Masculinity * Missionary I | 0.003 | ||||||||||

| Masculinity – Effectual L. | −0.04*** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect Masculinity * Darwinian I | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect Masculinity *Communitarian I | −0.01 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect Masculinity * Missionary I | 0.008 | ||||||||||

| LP Orientation – Causal L. | −0.04*** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect OLP * Darwinian I | 0.04** | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect OLP * Communitarian I | −0.002 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect OLP * Missionary I | −0.02 | ||||||||||

| LP Orientation – Effectual L. | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect OLP * Darwinian I | −0.02 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect OLP * Communitarian I | 0.004 | ||||||||||

| Moderator effect OLP * Missionary I | |||||||||||

| Adjusted R-squared Causal L. | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| Adjusted R-squared Effectual L. | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.34 |

| Q (2) Causal L. | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| Q (2) Effectual L. | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

Note: VIF<5 (Hair et al., 2011).

In evaluating the variance of the dependent latent variables explained by the constructs that predict them (R2), we see that the model explains a variance higher than 0.1 (Falk and Miller, 1992). While analyzing R2 as a criterion of predictive relevance, we also applied the sample reuse technique (Q2 through Blindfolding) proposed by Stone (1974) and Geisser (1975). The dependent latent variable Q2 is greater than 0, indicating the model's predictive validity. To evaluate the significance of the structural relationships, we applied the bootstrapping procedure (500 samples based on the original sample).

Table 7 shows the results of the different models. First (Model I). We analyzed the effect of the independent variables on the dependent variable to confirm Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3. Next (Models II–XI), we analyzed the effect of the moderator variables separately, as well as their interaction with the independent variables.

Our results show that Darwinian, communitarian, and missionary identities are positively and significantly related to causal and effectual logic, even though the t-statistics indicate very different degrees of relationship. The t-statistic shows that Darwinian identity (β=0.45, p<.001, Model I) is more closely related to causality and communitarian identity (β=0.12, p<.001, Model I) more significantly related to effectuation. The significances of the relationship between missionary identity and both logics are the same (β=0.12; β=0.12, p<.001, Model I). These data suggest that all three identities combine both logics in responding to uncertainty of the business environment. Based on the data, we accept H3 and we partially accept H1 and H2.

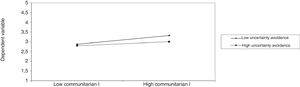

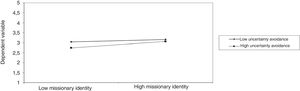

From Model II, we introduce moderation that may affect the relationships described above. The first moderator variable, “avoiding uncertainty,” is inversely related to both logics, and its moderator effect occurs only through use of effectuation by communitarian and missionary identities. Thus, as a communitarian entrepreneur's need to reduce uncertainty increases, he/she decreases use of effectual logic. We conclude that entrepreneurs make decisions based on causality, in a more planned way, using a fixed strategy. In the case of missionary identity, however, the relationship is positive and significant, indicating that these individuals use effectual logic to reduce the degree of uncertainty in their country. In the presence of uncertainty, missionary identity tends to be more flexible, attempting to adapt to events to benefit the firm.

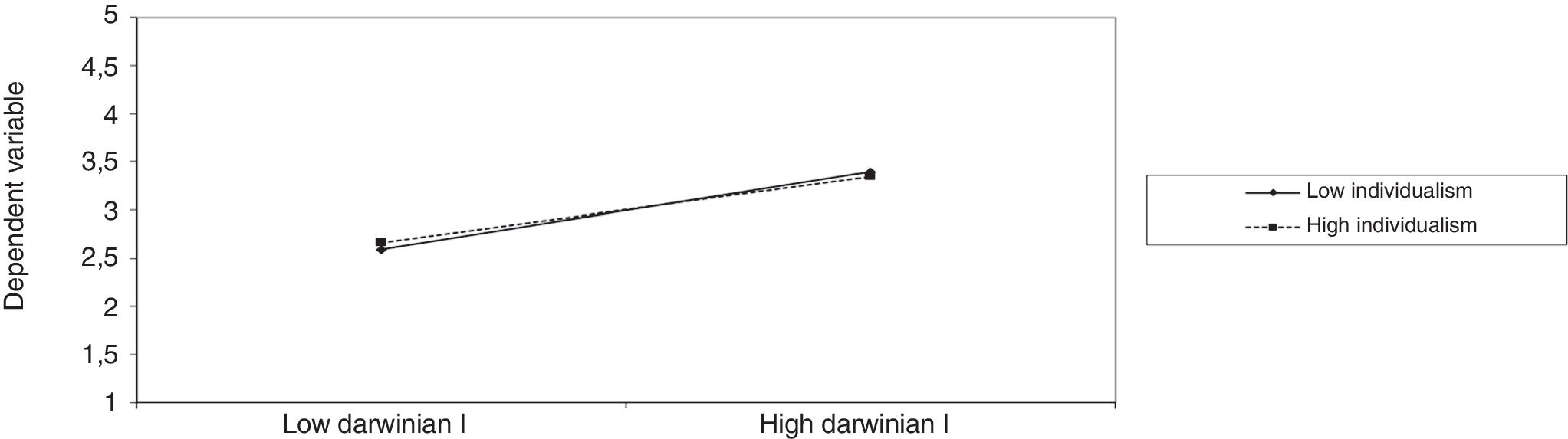

Individualism affects causal decision-making inversely, but individualism's moderator effect is significant and inverse when Darwinians use effectual logic. This result could indicate that Darwinian entrepreneurs use less effectual logic in cultures with high individualism. Although their identities focus on achieving economic benefit, the marked cultural dimension in this case leads these entrepreneurs to reinforce their strategy through rational logic to achieve the organization's objectives.

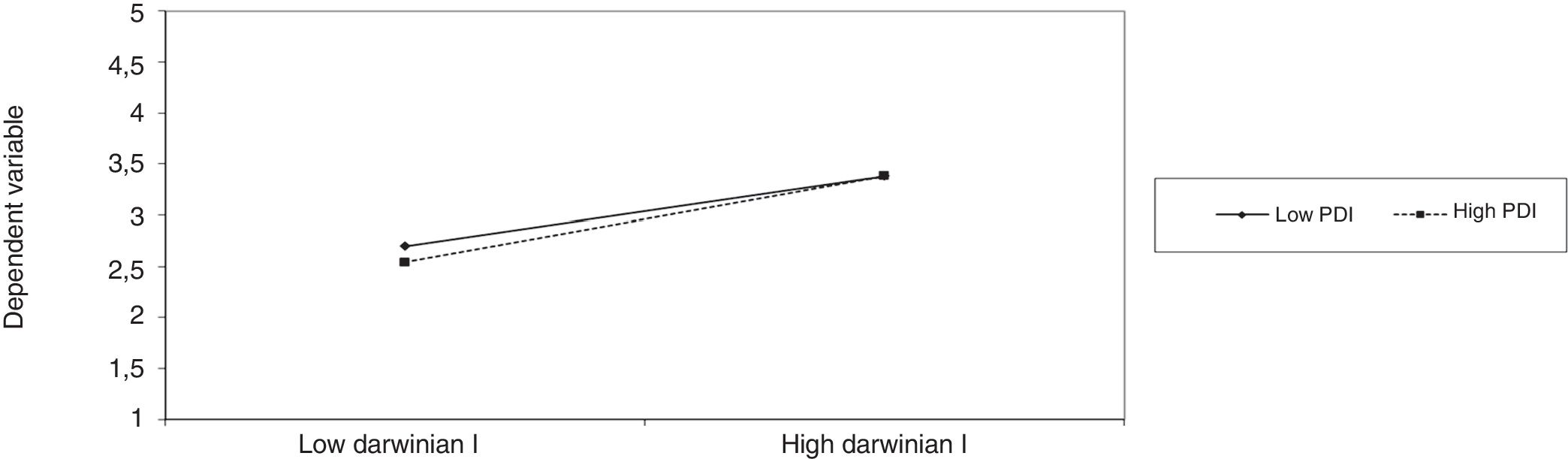

The score for “distribution of power” is based on the individual's acceptance of the fact that power is distributed unequally. The moderator effect of PDI is positive and significant when Darwinian and missionary identities use effectual logic. Less hierarchy in institutions and organisms lowers a country's score for this variable. Darwinian and missionary entrepreneurs tend to use experimentation and to be more flexible in decision-making in these situations, in which people receive fewer instructions from higher entities and thus are more open to experimentation and change, adapting to it and transforming possible threats into opportunities.

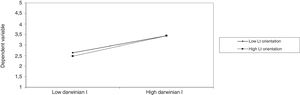

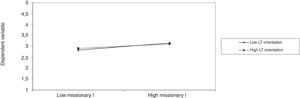

The dimension LTO intensifies the relationship between Darwinian identity and use of causal logic, since, according to Hofstede and Hofstede (2005), a culture oriented to the long term views the world as constantly changing, requiring that one always prepare for the future. This result indicates that Darwinian identities endorse rational decision-making and definite plans as means to adapt to change. In contrast, this dimension inversely intensifies the relationship between the missionary identity and use of effectual logic. Missionary identities reduce use of flexibility and experimentation through more rational logic to adapt to countries with high LTO.

Finally, the dimension masculinity does not significantly affect the relationship between the different social identities and the use of effectual and causal logic.

According to the data obtained, we accept H7, reject H8, and partially accept H4, H5 and H6. Since causality is based on prediction and the need to plan—insofar as the entrepreneur's goal is to establish a plan to achieve an end in whatever way possible, focusing on choice of the right means to achieve it—it is difficult for the cultural variables of the entrepreneur's country to raise or lower this effect (causal logic), since the entrepreneur takes these variables into account in design of the planning.

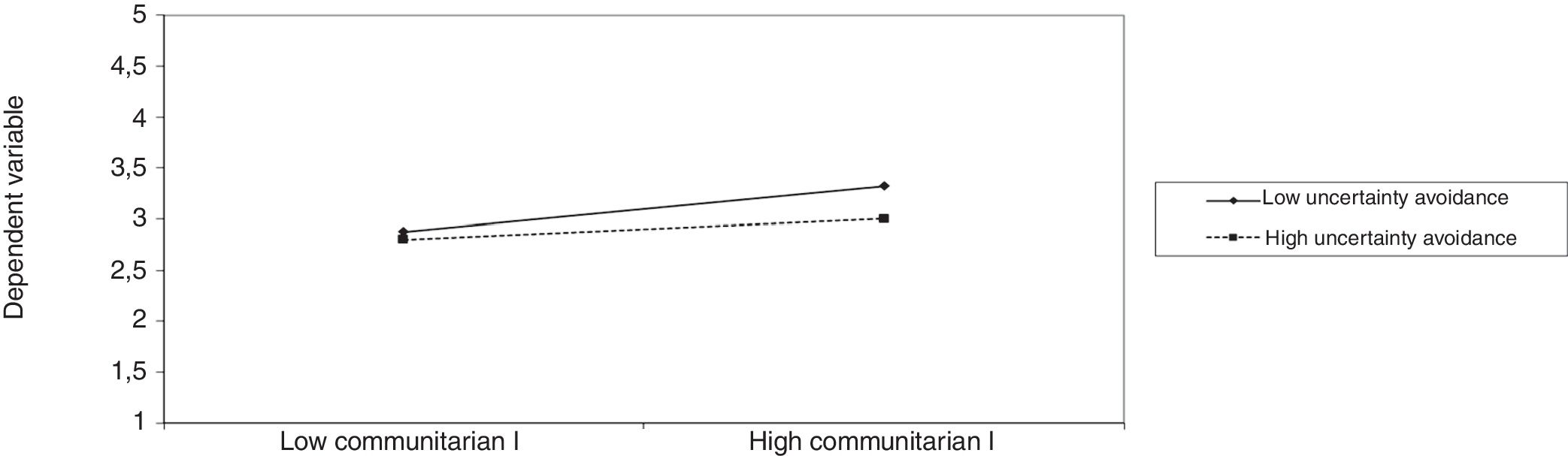

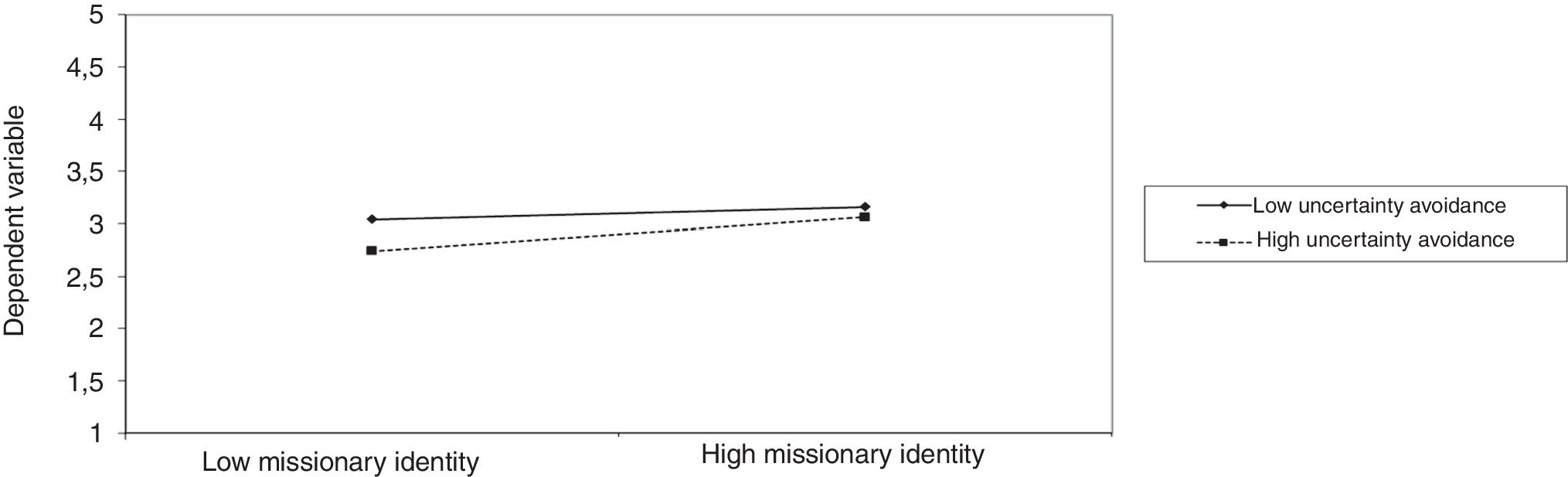

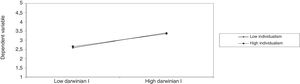

We also performed moderation analysis with a moderator effect. Figs. 1 and 2 show that uncertainty avoidance inversely moderates the relationship between effectual logic and communitarian identity (β=−0.06, p<.001) and positively moderates effectual logic and missionary identity (β=0.05, p<.01)

Fig. 3 presents the inverse moderator effect of individualism in the relationship between Darwinian identity and effectuation (β=−0.03, p<.05).

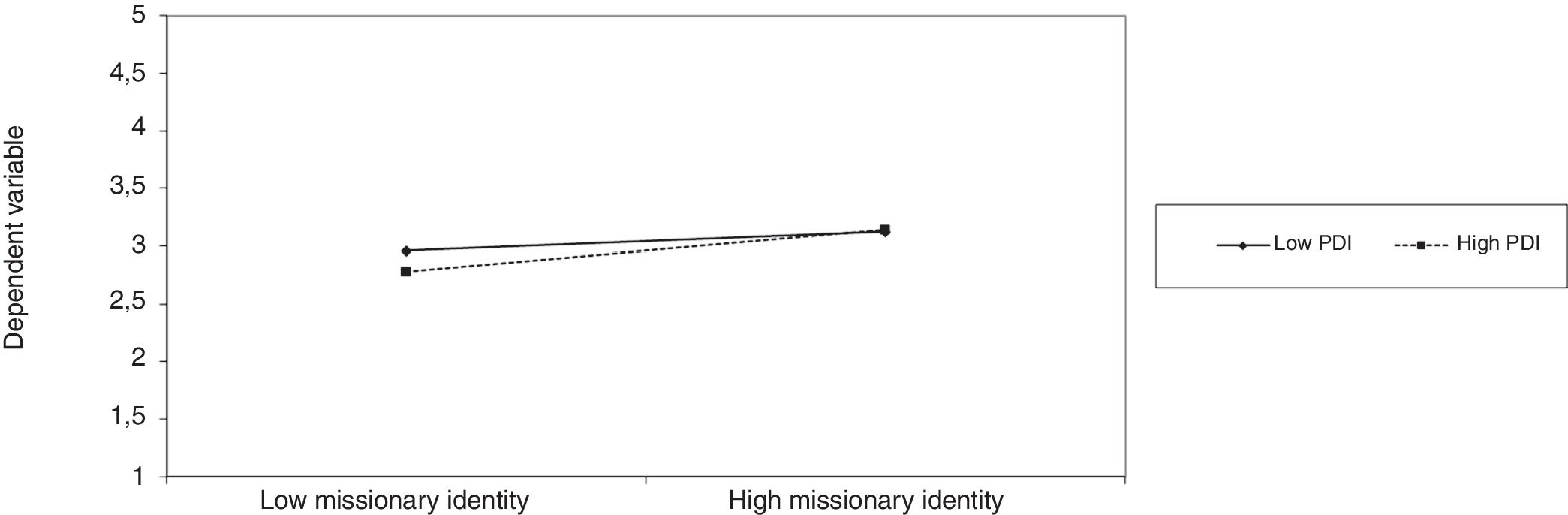

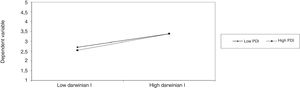

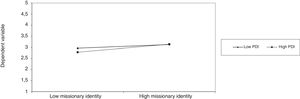

Figs. 4 and 5 show the moderator effect of the PDI in the relationship of effectual logic to Darwinian identity (β=0.04, p<.05) and missionary identity (β=0.05, p<.001).

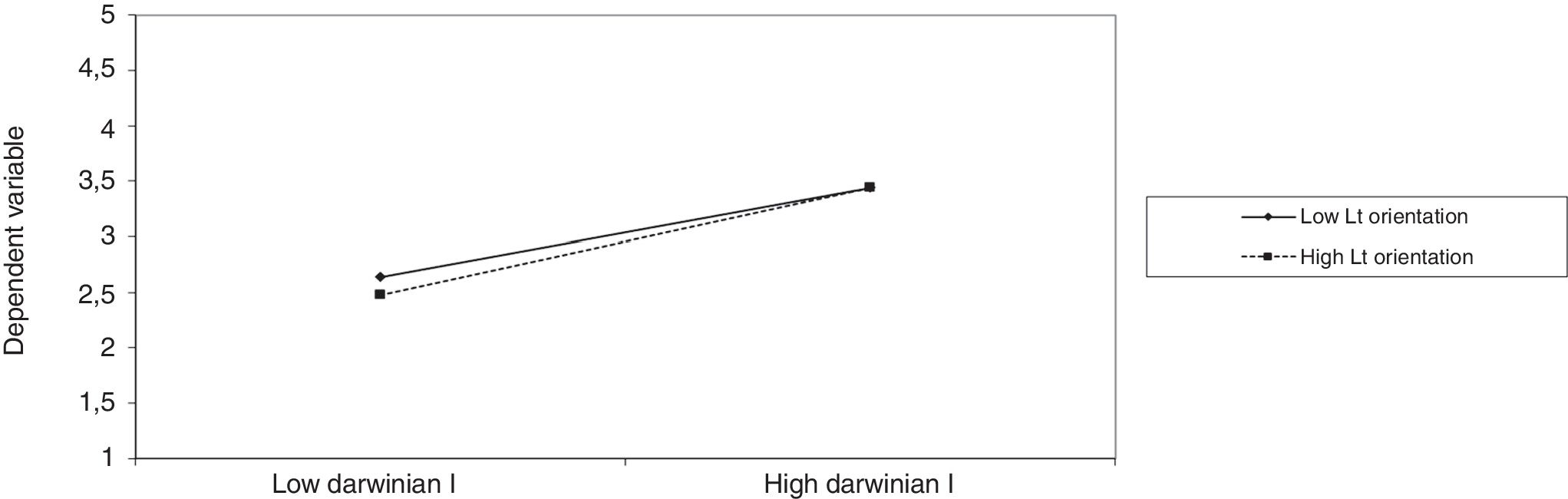

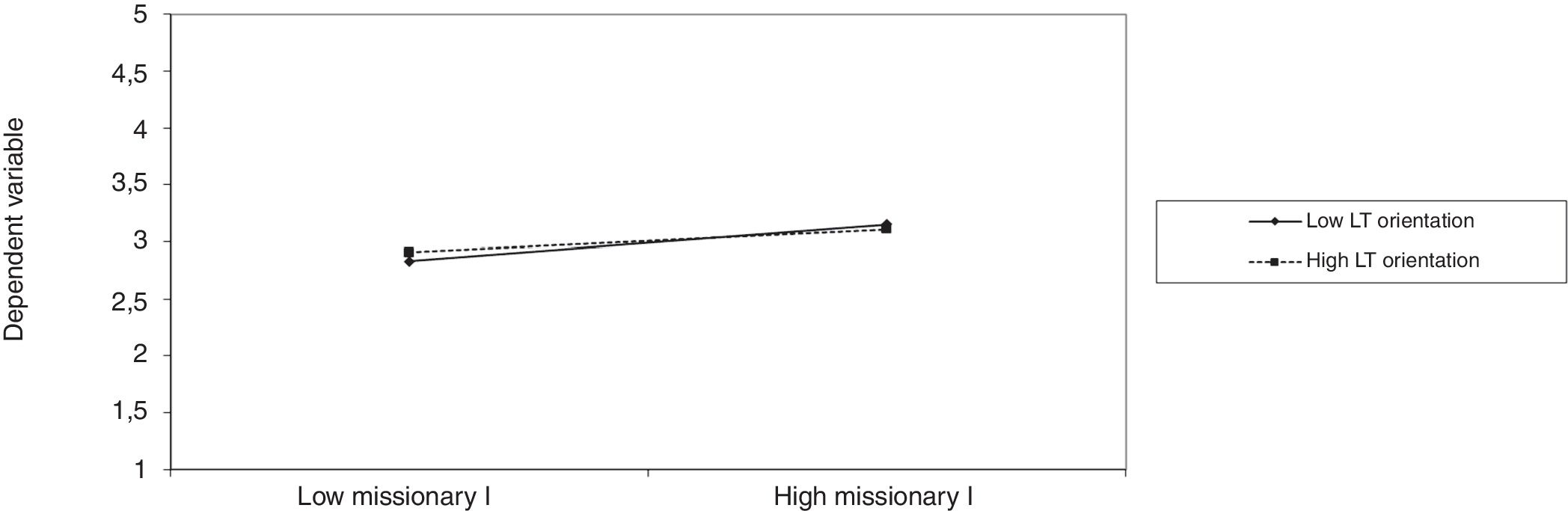

Finally, Figs. 6 and 7 show the moderator effect of LTO in the relation between causality and Darwinian identity (β=0.04, p<.01) and the inverse moderator effect in the relation between effectuation and missionary identity (β=−0.03, p<.05)

To conclude, the R2 levels indicate that the causal model partially explains the endogenous variables. The model fits well based on most of the indicators studied.

DiscussionThis study has analyzed the influence of social identities on use of causal and effectual logic, as well as the moderator effect of some cultural dimensions in this relationship: avoiding uncertainty, individualism, PDI, masculinity, and LTO. The study was contrasted using a sample of 5076 students who had created their own new ventures.

As to the relationships in the first model, our empirical evidence shows a significant relationship among the different social identities, causality, and effectuation, helping to confirm that entrepreneurs with very different identities may face very diverse situations when managing a new economic activity, a condition that requires making decisions based on planning and action. Some studies (e.g., Smolka et al. (2016)) propose that planned reasoning works better in decisions involving predictable results, while effectual reasoning is better applied in situations of uncertainty. Founders who use different logics in decision-making seem, however, to obtain better performance.

Based on the moderator effect of the cultural dimensions analyzed, this effect is significant in the case of effectual logic in most of the models analyzed. However, use of causal logic is only affected by the dimension LTO.

The case of communitarian identity shows an inverse effect in the dimension “avoiding uncertainty.” Since communitarian identity focuses on serving the community with innovative products, it uses less flexibility and experimentation in societies with higher avoidance of uncertainty. In this case, communitarians tend to use predefined plans, full information, and a general view of the impact of the product on the community.

Missionary identity is characterized by focus on a goal, advancing a social cause. Acting responsibly is the fundamental goal of such firms. For this identity, “avoiding uncertainty” has a positive moderator effect on use of effectuation, reaffirming the hypothesis that such entrepreneurs seek to make significant social contributions by adopting business models that provide creative solutions in uncertain markets. Mitchell et al. (2000), among others, confirm that decisions associated with creating a firm vary from culture to culture. These decisions include protection of the knowledge developed, access to resources, good will (e.g., tolerance for commitment and motivation), and recognition of opportunity—all associated with decisions linked to new business ventures, both individually and in interaction with others.

The relationship of PDI is also significant and intensifies decisions involving effectuation. We deduce that adoption of creative decisions intensifies because missionary entrepreneurs focus on tackling complex social problems. Finally, this identity is inversely moderated by LTO. This result confirms that missionary identity uses the new venture as vehicle to achieve its social and/or environmental goals through effectual or causal logic depending on the situation. Countries with more marked LTO tend to use effectual logic less to achieve their goals.

As mentioned above, Darwinian identity, whose ultimate goal is to obtain classic benefits, is influenced by PDI in its relation to effectuation. We confirm that this cultural dimension influences effectual decision-making. Some studies (Mitchell et al., 2000) find that this dimension influences arrangement, ability, and behavior cognitions, which in turn affect decisions to start up. The relationship of this identity to causality is influenced by LTO, a dimension oriented to obtaining future rewards and perseverance, conditions closer to the use of pre-established plans, security, and personal stability.

Finally, we conclude that “masculinity” has no significant effect on the relationships among the different social identities and the use of effectual and causal logic.

The results obtained imply that Hofstede's cultural dimensions—avoiding uncertainty, individualism, PDI, masculinity, and LTO—are important to the debate effectuation-causality debate. Our study focuses on 33 countries whose dimensions differ greatly and obtains significant effects in the processes used. These findings indicate that the scores in these dimensions are related to specific social identities and their use of effectual logic.

ConclusionsThis paper sought to answer the primary question of how the different social identities use effectual or causal decision-making and whether national culture can influence this relationship. Through a social identity perspective, we show that Darwinian identity alone has a stronger effect on effectual than on causal reasoning. This result implies that Darwinians focus on their entrepreneurial and planned goals as their main motivation. This is the only identity in which use of causal logic is influenced by LTO. Even when we consider predefined plans and certainty, these entrepreneurs intensify their decisions in countries whose cultures are oriented to and prepare for the future.

For communitarians, the basic social motivation as founder is to support and be supported by a community. For these founders, the means proposed by Sarasvathy (2001) are fundamental to effectual logic: identity and social network. This finding helps us to confirm a stronger tendency to use effectual logic in decision-making. Since this type of founders’ primary reference group is their community (Fauchart and Gruber, 2011), national culture influences their identity as entrepreneurs, including their social network. For communitarians, uncertainty avoidance deserves special attention, as product innovation is the center of their business process. Cultures with higher scores in this dimension could inversely influence their decision making from effectual logic.

Finally, as the model data show, missionary founders use causal and effectual logic in a complementary way. This finding supports the assertion that missionary identity focuses its efforts on a very specific goal when it faces highly uncertain markets. Such founders’ use of effectual logic is intensified by distance from power and uncertainty avoidance. Thomas and Mueller (2000) find that entrepreneurs in cultures with little uncertainty are more likely to exploit any relationship based on trust, whereas entrepreneurs in a culture with high impact in this dimension are more likely to persist in relationship-based trust, despite the threat perceived in the environment. This conclusion supports Fauchart and Gruber (2011), who affirms that such founders only commit to suppliers with the same type of identity as themselves.

This study advances knowledge of the entrepreneurial phenomenon based on the individual's identity—not only on the type of opportunity he/she exploits or the purpose of entrepreneurship. It also helps us to confirm that the entrepreneurial phenomenon is complex and requires deeper study of individuals and their sociological characteristics.

These results yield implications with potential for use in both theory and practice.

First, we introduce the influence of culture in the field of effectuation and causality. Perry et al. (2012) recommended exploring the relationships between effectual logic and established cultural tendencies to deepen understanding of the next stage of development of this field. Second, the results show that culture moderates communitarian and missionary and Darwinian identities in their relationships to effectuation in most of the cases studied. Thus, elements of effectual reasoning are used by all business owners, are not influenced by culture, and differ among countries. Entrepreneurs should thus consider the possible influence of national culture on decision-making. The potential negative influence of national culture on use of effectuation could indicate that it is better to use causal logic.

Third, this study develops the relationship between the different social identities and cultural dimensions, since, as mentioned in the theoretical framework, an individual's identity is connected to his/her national culture of origin (Berger, 1991). In analyzing validation of the scale used in this study, Sieger et al. (2016) conclude that entrepreneurs’ cultural traits may influence their social identities and recommend further research on this issue.

These findings have various implications for practice. First, the study results suggest that culture should be taken into account as a factor in entrepreneurship training. This study concludes that only individuals with specific social identities are influenced by uncertainty, individualism, distribution of power, and LTO.

Second, the results of study influence how entrepreneurs face decision-making in their own countries and how they should make decisions when entering foreign markets, an increasingly common option due to the decreasing price of new information and communication technologies.

Despite these contributions, our study has limitations that open new research opportunities. The first limitation involves the sample. We analyze firms created by university students and do not include, for example, the role of expert entrepreneurs in the study of causal and effectual decisions. Future studies should analyze experienced entrepreneurs to confirm the implications of experience for decisions and cultural dimensions. The second limitation involves control variables, as the study would be enriched by their introduction. Future studies should include variables such as age, sex, and activity sector to gain fuller knowledge of their implications.

The third limitation is the transversal design of the research, which prevents strict causal inferences. Future research could undertake new empirical studies based on long-term designs to obtain new evidence to improve understanding of the influence of identities on the different stages of the business process.

Interesting future lines of study include deepening understanding of the second-order dimensions that compose effectual logic and analyzing how each dimension is influenced by the different cultural dimensions. Other lines of study could analyze dimensions not considered here through comparative study of countries with opposing dimensions. Such analyses could help us to develop fuller knowledge of the individual culture of each entrepreneur and how it interacts with causal and effectual decisions.

FundingThis research has been supported by the Spanish “Ministerio de Economia, Industria y Competitividad” (Ref.: ECO 2013-45885-R and ECO2016-80677-R).