In the context of an economic and financial crisis characterized by scarce munificence and high uncertainty, we examine the role of organizational ambidexterity in SMEs survival, and the TMT and ownership characteristics that influence ambidexterity. Our analysis of Spanish manufacturing SMEs in the context of an international economic crisis suggests that: (1) firm survival is associated with ambidexterity; (2) diversity in TMT tenure improves firm ambidexterity and (3) a negative effect exists between family ownership and ambidexterity, but (4) a positive effect exists between family ownership and survival.

This study contributes to our understanding of the antecedents of SME ambidexterity by providing a theoretical model that combines the arguments of upper-echelons theory with those found in family-firm research offering an extended view of corporate elites in SMEs. Our research highlights and provides support to the superiority of ambidexterity for survival under external (crisis) and internal (SMEs) restrictions.

The last Great Recession, which started in 2008, has had very negative effects on European companies, many of which have not been able to overcome the simultaneous decrease in demand and the significant reduction in available financial credit (OECD, 2009). The significant rise in business mortality rates during this last economic and financial crisis (OECD, 2018) has reopened the debate and the interest regarding the survival of companies facing external crises (Linnenluecke, 2017). A key element, but also a controversial one, in explaining the persistence of companies is ‘organizational ambidexterity’ (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2013).

Organizational ambidexterity is defined as the ability of an organization to be simultaneously efficient in its management of today's business demands – also called exploitation orientation – and adaptive to changes in the environment, called exploration orientation (Duncan, 1976). It is a key construct in management research, due to its strong theoretical link with long-term financial performance and survival, and its empirical link with short-term performance (Junni et al., 2013; O’Reilly and Tushman, 2013).

However, despite this general accepted assumption, research raises theoretical doubts about the convenience of organizational ambidexterity in contexts characterized by external and internal restrictions.

Regarding external constraints, such as the context of the last economic crisis in which munificence was very low, research suggests that it can be dangerous to deploy ambidexterity orientation, and that organizations are better served by focusing on exploitation, given the strong pressures on efficiency and prices (Cao et al., 2009; Gulati and Puranam, 2009; Raisch and Hotz, 2008).

On the other hand, other authors raise questions about the relevance of ambidexterity in contexts with certain internal restrictions, especially for firms with significant disadvantages in terms of management expertise, access to capital, talent, and limitations on the development of slack resources, such as small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (Ebben and Johnson, 2005). In this context, it appears to be less feasible for SMEs to become ambidextrous than for larger firms, which have greater and more diverse resources, as well as more ways to become ambidextrous, as e.g. through structural ambidexterity (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2011). For these reasons, some researchers suggest that SMEs should concentrate all of their efforts and resources on either explorative or exploitative activities, rather than on both, in order to survive a crisis (Ebben and Johnson, 2005; O’Reilly and Tushman, 2011).

As far as we know, no study has considered both contexts together, i.e. SMEs and a profound external crisis, leaving an important research gap which requires additional research into the ability of SMEs to be ambidextrous and into the positive or negative effect of organizational ambidexterity on survival, in these particular contexts.

Although there is abundant literature that studies the drivers of organizational ambidexterity in large companies, in the case of SMEs the literature is scarce. There is some research that tries to answer how SMEs become ambidextrous (Lubatkin et al., 2006). These studies argue that ambidexterity is a dynamic capability that requires the development of sensing, seizing and transforming activities, which relies on managers who play a significant role in integrating the contradictory demands of exploration and exploitation.

In SMEs, in situations where their survival is at risk, we argue that an extended view of upper echelons – i.e., not only managers but also owners – could play key roles in achieving ambidexterity. Based on an amplified view of the upper-echelons theory, we argue that decision-making capabilities that allow SMEs to sense environment change and to seize explorative and exploitative alternatives rely on the SMEs’ top management teams (TMTs) diversity, while capabilities that allow the reconfiguration of resources rely on SMEs’ owners. Specifically, we follow researchers that state that tenure diversity within the TMT affect the ability of upper echelons to process information (i.e., the ability to sense environment change), to look for alternatives, and to make strategic decisions associated with different levels of risk taking (McClelland et al., 2011, 2010; Simsek, 2007). Moreover, we suggest thereby it enables the organization to respond to the environment change, combining exploitation and exploration in a balanced way.

TMT tenure diversity can improve sensing and seizing, but ambidexterity requires also transforming which relates to reconfiguring resources and modifying priorities. We argue that among SMEs, changes in firms’ priorities will rely on their owners. In fact, research suggests that family ownership is associated with the discretion to manage, assign, add to, or dispose of the firm's resources in order to exploit and explore (De Massis et al., 2014; Veider and Matzler, 2016).

Compared with large firms, the interaction in SMEs between managers and owners is close and frequent; even more so in the case of family owned firms in which the roles of managers and owners are interlaced. We propose that in SMEs both management and ownership characteristics could offer unique insights into how upper echelons can sense, seize, and reconfigure resources in order to become ambidextrous. Additionally, SMEs under a constrained and financial distress environment face decisions related to survival or not, to bankruptcy or solvency. In this critical environment, SMEs have to make key decisions about their financial structure, i.e. regarding temporary liquidity shocks or reduced access to bank finance, about the divestment of key assets to recover or about the level and scope of workforce reductions (McGuinness et al., 2018). We argue that an extended view of upper echelons, which includes managers and owners, may better explain SMEs ambidextrous decision making and behavior in deep external crises.

Our study makes several contributions. First, we contribute to the growing literature on organizational ambidexterity by investigating its impact on survival in a context of external (economic and financial crisis, low munificence environments) and internal (SMEs) restrictions. Second, we propose an extended view of upper echelons that includes managers and owners in order to explain SME's behavior and actions under survival threats. Third, we add to the family firm and ambidexterity literature, focusing on the impact of family ownership on SMEs ambidexterity and survival. Finally, we contribute to the SMEs literature by offering evidence of the positive consequences of ambidexterity for SME survival in environments of low munificence.

In the next section, we review the literature and present our hypotheses. We first examine an extended view of upper-echelons as antecedent of organizational ambidexterity. We follow by analyzing the relationship between family ownership, ambidexterity and survival. After describing our research method, we present our empirical findings, which derive from data on Spanish manufacturing SMEs. We conclude with a discussion of the results, as well as their implications and issues for further research.

Ambidexterity in SMEs: The role of extended upper echelonsAmbidexterity has been studied from different perspectives, including organizational learning (Levinthal and March, 1993; March, 1991), organizational behavior (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004), technological innovation (He and Wong, 2004), and the organizational theory of dynamic capabilities (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2008). In our study we rely on the latter, defining dynamic capabilities as an organization's ability to integrate, construct, and reconfigure internal and external competencies in order to quickly deal with changing environments (Teece et al., 1997). According to O’Reilly and Tushman (2008), the capabilities that firms need to be successfully ambidextrous are consistent with Teece's (2007) tripartite taxonomy of sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring or transforming.

Due to the fact that SMEs lack the volume of slack resources and the sort of hierarchical administrative systems that can help them address the contradictory information and knowledge processes that ambidexterity demands, they have to rely more on their upper echelons to attain ambidexterity (Lubatkin et al., 2006). In SMEs, we argue for an extended view of upper echelons, i.e. that takes into account the role of managers and ownership playing key and diverse roles in sensing, seizing and transforming (Lubatkin et al., 2006; O’Reilly and Tushman, 2011, 2013).

In that sense, Hambrick and Mason (1984) started the stream of research on upper echelons, focusing mainly on the key role of top managers in firms’ behavior. A TMT is the “small group of most influential executives at the apex of the organization – usually the CEO (or general manager) and those who report directly to him” (Finkelstein et al., 2009: 10). Finkelstein et al. (2009) state that in smaller firms owners may be more active by increasing their involvement from the traditional role as monitors of strategic results to strategic formulation and selection, and thus the upper-echelons theory could be extended to include owners. In SMEs, TMT members have numerous and close ties to other upper-echelon members in contrast to the typical situation in larger firms. Consequently, owners and executives will influence the strategic orientation of the firm (Rivas, 2012) and may have specific effects on SMEs’ capabilities (Chen, 2011; Simsek et al., 2015). Additionally, we argue that managers and owners should have a different role in sensing, seizing and transforming.

As Teece (2007) states, sensing capabilities require firms to obtain and interpret information and shape it in new ways; more specifically, upper echelons should have the skills needed to shape novel information and to avoid getting trapped in the experiential, well-known, and usual sources of information. Sensing demands that a TMT fosters learning, accepts failure, and challenges the status quo (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2008). On the other hand, seizing capabilities require the development and sharing of strategic intent, an ability to think “outside the box,” and avoidance of the usual mindsets. To address opportunities, some formal decision-making rules must be broken and bureaucratic features that reinforce the status quo must be overcome (Teece, 2007). Therefore, seizing capabilities require creativity and the acceptance of uncertainty and risk by the TMT of SMEs. Finally, transformation implies reallocating assets and resources to capture new opportunities; it also involves accepting changes in the orchestration of the firm's assets and a shared commitment to such changes, as well as the power and discretion to execute decisions (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2008; Teece, 2007).

Therefore, in SMEs we suggest that sensing and seizing relate to the TMT's decision-making capabilities for analyzing diverse and rich information, and for creating alternatives that break with the status quo. However, transforming, i.e. the reconfiguration of assets, appears to be related to ownership issues. Reconfiguring requires the discretion, commitment, and power to allocate firm resources among alternatives and to maintain them over time (Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1990; O’Reilly and Tushman, 2011).

Additionally, this extended view of upper echelons, i.e. taking into account the role of managers and owners, may be more necessary under extenuating conditions. The financial crisis and the subsequent economic downturn led to dramatic reductions in both aggregate demand and bank lending for SMEs across the EU. As McGuinness et al. (2018: 83) state “according to European Commission data, during the period of 2008 to 2011 loans to SMEs of less than €1 million declined at an average of 47% against the pre-crisis peaks with falls in the region of 66% in Spain. Furthermore, Spanish SMEs report the greatest losses in employment, turnover and profitability compared to SMEs in other European countries”. As a consequence, in this constraining and financial distress environment, SMEs need to make key decisions about their financial structure for survival (they are more likely to experiment temporary liquidity shocks and constraints in their access to bank finance, and are more likely to rely on trade credit (McGuinness et al., 2018)). In addition they need to reassign key assets to recover or to define the level and scope of workforce reductions, and it is not only managers but mainly SME owners who will influence their direction. When decision making is related to the reassignment of resources in order to survive or die, bankruptcy or solvency, owners will influence SMEs behavior.

SMEs ambidexterity and TMT tenure diversityThe upper-echelons theory (Hambrick and Mason, 1984) studies the relationship between upper-echelon characteristics, such as values and experiences, and firm behavior and performance (Finkelstein et al., 2009). The number of demographic characteristics, job related (e.g. functional diversity, educational diversity) and non-job related (e.g. age or gender diversity), is enormous, but each of them is linked to certain specific psychological factors (García-Granero et al., 2017). In that sense, executive tenure is a demographic characteristic associated with three main psychological factors: commitment to the status quo, risk aversion and limited information processing (Finkelstein et al., 2009). Therefore, we expect that executive tenure will be highly relevant for decision making on exploitation and exploration because it affects information processing, commitment to the status quo and attitudes toward risk taking (McClelland et al., 2010, 2011; Simsek, 2007), especially in relation to strategic choices that involve complexity and uncertainty (Chen, 2011). In this line the effect of observable characteristics of executive tenure – such as age (proxy of tenure in career) or time spent in top management positions (proxy of tenure in position) – on decision making has been extensively studied (McClelland et al., 2010; Wiersema and Bantel, 1992).

Concerning age, older TMT members tend to be more risk averse and they prefer alternatives with short-term outcomes. They have their own “recipes” that have been proven in the past and they tend to develop a commitment to the status quo. Wiersema and Bantel (1992) argue that people tend to become more rigid, inflexible, and resistant to change as they age. In other words, they tend to behave in a more exploitative manner. When the TMT incorporates younger people, and age diversity increases, it may be better able to take advantage of opportunities that demand changes in the firm and thereby improve the firm's seizing capabilities. Chen (2011) provides evidence of the role of TMT age in risky and uncertain strategic situations, such as an organization's internationalization regarding emerging economies. Moreover, some studies find evidence of the influence of age diversity on proactive behaviors and risk taking (Escribá-Esteve et al., 2008; Wiersema and Bantel, 1992). This tenure diversity implies that the different time horizons of the careers of TMT members affect the decision-making processes and that the degree of compromise in relation to new projects varies as a result. The tendency of older TMT members to focus on the status-quo and to exploit well-known solutions during an external economic and financial crisis will be balanced by younger TMT members, who are expected to focus on novel and innovative projects. Therefore, this tenure diversity in the TMT could help SMEs not only focus on exploitative alternatives but also explore new opportunities, which should enhance their ambidexterity.

With respect to tenure in position, it has consequences for information processing (e.g. different scopes of vision, perception, and interpretation; Fernández-Mesa et al., 2013; McClelland et al., 2010). The upper-echelons literature links this tenure diversity with the richness of information sources, and with the amplitude and variety of analyses utilized in decision-making processes. Wiersema and Bantel (1992) argue that team members with similar tenures have undergone the same socialization process, and share similar management experiences and problems. However, heterogeneous TMTs rely on a variety of information sources, have numerous points of view, consider more alternatives, favor the exploration of ideas, and offset the tendency to exploit well-known areas. Moreover, tenure diversity decreases the tendency to engage in group thinking (Milliken and Martins, 1996; Simons et al., 1999).

Gedajlovic et al. (2012) state that decision making processes are comprehensive when TMTs can evaluate a number of opportunities and apply multiple criteria. They argue that comprehensive processes influence ambidexterity. This implies a need for exhaustive processes for sensing the environment—processes that allow for discovering, identifying, and evaluating multiple opportunities and alternatives. Therefore, ambidexterity requires divergent thinking to identify and evaluate—in order to sense—exploration opportunities. It also requires convergent thinking for exploiting those opportunities (Lubatkin et al., 2006). The diversity in experiences that arises from tenure diversity contributes various points of view, and enhances the richness of the criteria used to identify and evaluate alternatives. As such, it facilitates more comprehensive processes.

Tenure diversity could be specifically useful for achieving ambidexterity when there are changes in economic conditions, and even more so if they are sudden, profound and quick. In one year in Spain, the national index of economic activity changed from positive rates in the first semester of 2008 to negative rates in 2009 (INE database). From a financial point of view, Crespí and Martín-Oliver (2015) argue that Spain constitutes an ideal framework to study the effect of financial restrictions and a credit crunch on non-financial companies because their basic source of external funds is bank debt and this was added to a solvency crisis in Spanish banks which reduced the supply of available bank credit. In that sense, according to the European Commission data, during the period of 2008 to 2011, loans of less than €1 million to SMEs declined by an average of 66% in Spain against the pre-crisis peaks (McGuinness et al., 2018).

As Schmitt et al. (2010) state, management research has largely analyzed the ambidexterity premise under stable or growing environmental conditions. However, during the sub-prime crisis in late 2008 the resulting organizational challenges were completely new and qualitatively dissimilar to those associated with growth. Under these challenges, tenure diversity will favor the sensing of the first signals of change through enriching information processing, as well as improving the likelihood of breaking the commitment to the status quo, lowering risk aversion, and offering novel answers and enforcing ambidexterity. This leads to our first hypothesis:Hypothesis 1 In an environment of financial and economic crisis in SMEs, TMT tenure diversity is positively related to the firm's ambidexterity.

As we noted above, in the context of an external financial and economic crisis, achieving ambidexterity in SMEs requires specific capabilities not only for sensing and seizing but also for transforming resources. In SMEs ownership could be relevant to help explain transforming, because it demands power and discretion to reassign key resources. According to Mintzberg's (1983) seminal work on power in organizations, two central dimensions for evaluating the power of ownership are the owners’ involvement1 and the ownership concentration. As Mintzberg (1983) states, the more involved the owners and the more concentrated their ownership, the greater their power in the company. Following this line, we argue that family ownership, defined by the majority of stock in the hands of a family, could play a key role in achieving ambidexterity in SMEs. The owners of family SMEs could use their significant power to initiate change and ensure execution of decisions in order to achieve the desired outcomes; family ownership grants them the power and freedom to explore and renew the firm (Veider and Matzler, 2016) and to control and monitor efficiency improvements (Hiebl, 2015). Moreover, family ownership increases attachment in decisions, strengthens control, and accelerates decision making (Boeker and Karichalil, 2002; Le Breton-Miller and Miller, 2006). This suggests that in SMEs family ownership provides the power and discretion needed to reconfigure resources in order to explore or exploit under a changing environment.

However, while ability (having the power and discretion) is demanded, willingness is also needed because the characteristics of family firms may affect their decisions on exploration, exploitation and ambidexterity (Nieto et al., 2015; Veider and Matzler, 2016).

In respect to exploration, family business scholars agree that family-owned firms have a conservative vision and tend to avoid decisions that may increase risk and uncertainty such as innovation investments (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2010; König et al., 2013). There are several reasons for this unwillingness to innovate, such as risk aversion or an interest to protect and preserve their socio-emotional wealth (SEW) (Sciascia et al., 2015; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2014), as well as their loss aversion attitude being more concerned with avoiding losses than with obtaining gains in order to preserve their SEW (Chrisman and Patel, 2012). On the one hand, according to agency arguments, the wealth of SME family owners is often completely invested in the firm and this wealth concentration increases their sensitivity to uncertainty and affects their preferences regarding investments in their companies (Anderson et al., 2003; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2014). On the other hand, according to SEW researchers, the high level of power of family owners over the company and the close ties between the family and the firm result in socioemotional endowments that family members wish to preserve and reinforce (e.g. the maintenance of family influence) (Berrone et al., 2010; Zellweger et al., 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2014). Nevertheless, those non-economic goals may have a negative effect on a family's innovation behavior (König et al., 2013). Consequently, because of all these factors, family-owned SMEs could have difficulties to achieve exploration.

Contrary to this negative view, from a long-term perspective other authors state that family-owned firms, because of their main interest to transfer the company to the following generations, will show a greater concern to develop the necessary skills to look for new business opportunities, which allows them to be explorative (Kellermanns and Eddleston, 2006). Other researchers link power concentration in family-owned firms to exploration on grounds other than long-term incentives and continuity. Family ownership increases discretion, which in turn allows for investments in new opportunities. Researchers adopting this view argue that family-owned firms are more skillful at exploration, creating new products, entering new markets, and adapting to the environment (Gedajlovic et al., 2004; Schulze and Gedajlovic, 2010).

While researchers provide both positive and negative arguments of family owners’ willingness to explore, the empirical evidence on large public firms seems2 to be in favor of the negative view (Block, 2012; Block et al., 2013; Chen and Hsu, 2009; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2014; Muñoz-Bullón and Sánchez-Bueno, 2011). For example, Chen and Hsu (2009) demonstrate that family ownership is negatively related to R&D investments. They argue that family ownership will reduce the motivation to invest in long-term R&D projects due to the wealth invested in the firm and the risk aversion of losing it, as well as the lower level of qualified staff, and the myopic behavior amongst other reasons. Also, in 964 large public firms, Chrisman and Patel (2012) found evidence that R&D investments were lower in family firms compared to non-family firms.

Regarding exploitation, we state that family ownership may enable exploitation through incentives to closely monitor a firm's operations and through taking the necessary steps to ensure that costs are contained, production is efficient, and resources are efficiently used (Carney, 2005; Gedajlovic et al., 2012); family ownership will closely monitor operations and take the necessary actions to address inefficiencies (Gedajlovic et al., 2004). Thus, family ownership provides both strong incentives and the discretion needed to refine and improve existing capabilities to become exploitative. These capabilities in the family firm are added to the natural tendency of companies in favor of exploitation, given their observable and short-term returns, in comparison with those of exploration (March, 1991). Empirically, Hughes et al. (2017) found evidence in a sample of 129 family firms that exploitation is a key ingredient of performance for all of their family firm configurations.

In SMEs – that have limited internal resources – in a hostile context of economic crisis – i.e. of limited external resources – the pursuit of ambidexterity may demand that hard choices are made about where to allocate resources, to exploitation, to exploration or to both. We argue that under an economic and financial crisis, with increases of more than 100% on the rates of bankruptcy, with decreases in the supply of financial debt and with limited access to external financial capital (Blanco et al., 2016), the investment on risky, long-term oriented, explorative activities in SMEs will be less likely under family ownership which may perceive the survival of the firm as being at risk and thus increasing their loss aversion (Chrisman and Patel, 2012). In this context, family-owned SMEs may be specifically concerned with the SEW priorities of family members, with goals primarily related to a firm's survival in which increased efficiency is prioritized through controlling costs or through incremental innovation – i.e. through exploitation – but avoiding the risk and uncertainty of exploration (Block et al., 2013). This leads to our next hypothesis:Hypothesis 2 In an environment of financial and economic crisis, SMEs’ family ownership is negatively related to ambidexterity.

In an environment of crisis family-owned SMEs will be motivated to direct the firm toward its particularistic goals, economic and non-economic ones. As discussed before, family-owned SMEs have some idiosyncratic characteristics that differentiate them from their counterparts of non-family firms. Do these characteristic features allow family-owned SMEs to better weather the economic crisis for survival?

The recent crisis has meant a significant restriction of financial resources for companies, especially for SMEs. In the Spanish case, credit was rationed and finance suppliers and banks strengthened credit conditions for firms or in some cases the access to funding was stopped (Crespí and Martín-Oliver, 2015; Blanco et al., 2016; McGuinness et al., 2018). As a result, firms found it very difficult to finance their activities, whether they were current or new projects.

On the one hand, in their interest to safeguard family control in the company and preserve their socio-emotional wealth, family-owned SMEs are reluctant to use external funds (Romano et al., 2000; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007), preferring to finance the company through the money of the family or through undistributed benefits. In fact, the reinvestment of profits – self-financing – is the main source of financing of family-owned SMEs. On the other hand, family-owned firms have long-term goals and they focus on activities that create and preserve the wealth of the family (Anderson and Reeb, 2003; Le Breton-Miller and Miller, 2006). As a consequence, during downturns family-owned SMEs will be willing to seek funding if necessary in order to achieve these goals. In this case, due to their long-term commitment and reputation, family-owned firms may access credit more easily as lenders perceive that their interests coincide with those of the family-owned firm (Crespí and Martín-Oliver, 2015).

Crespí and Martín-Oliver (2015) found strong evidence in a panel of more than 14,000 private family firms of a better access to external finance of family firms during the last economic crisis. They argue that due to the fact that agency costs could be lower in family firms because of their long-term orientation, the lender will perceive that their interests coincide more with the ones of the family firm, and provide better conditions in the loan contract. Additionally, the strong solid relations built with stakeholders during periods of expansion could reduce agency costs and may diminish the lenders’ perceptions of risk regarding family firms (Crespí and Martín-Oliver, 2015). Trade credit is a very relevant source of finance for SMEs and, as McGuinness et al. (2018) find evidence in a sample of 202,696 non-financial unlisted EU SMEs, an increase in trade credit in an economic and financial crisis improves the likelihood of survival. Thus, the above reasons will allow family-owned SMEs to better weather the economic crisis and survive.

We found additional arguments from a SEW perspective. We state that under an economic and financial crisis, in which there is an increase in the likelihood or probability of bankruptcy, the financial goals linked to survival converge with the family SEW goals (Chua et al., 2018). Bankruptcy may end with a loss of the family patrimony (owners will be the last creditors to be remunerated at bankruptcy). Furthermore also it could end with the SEW of the family firm with losses related to family identification, because bankruptcy may damage their family image and reputation, their emotional endowments and the likelihood of dynastic succession (Berrone et al., 2012). In such an environment, survival will be a goal in which family-owned firms will outperform non-family firms because the family oriented financial benefits of survival will be complementary with the non-financial benefits of survival (Chua et al., 2018). Hence,Hypothesis 3 In an environment of financial and economic crisis, SMEs’ family ownership is positively related to survival.

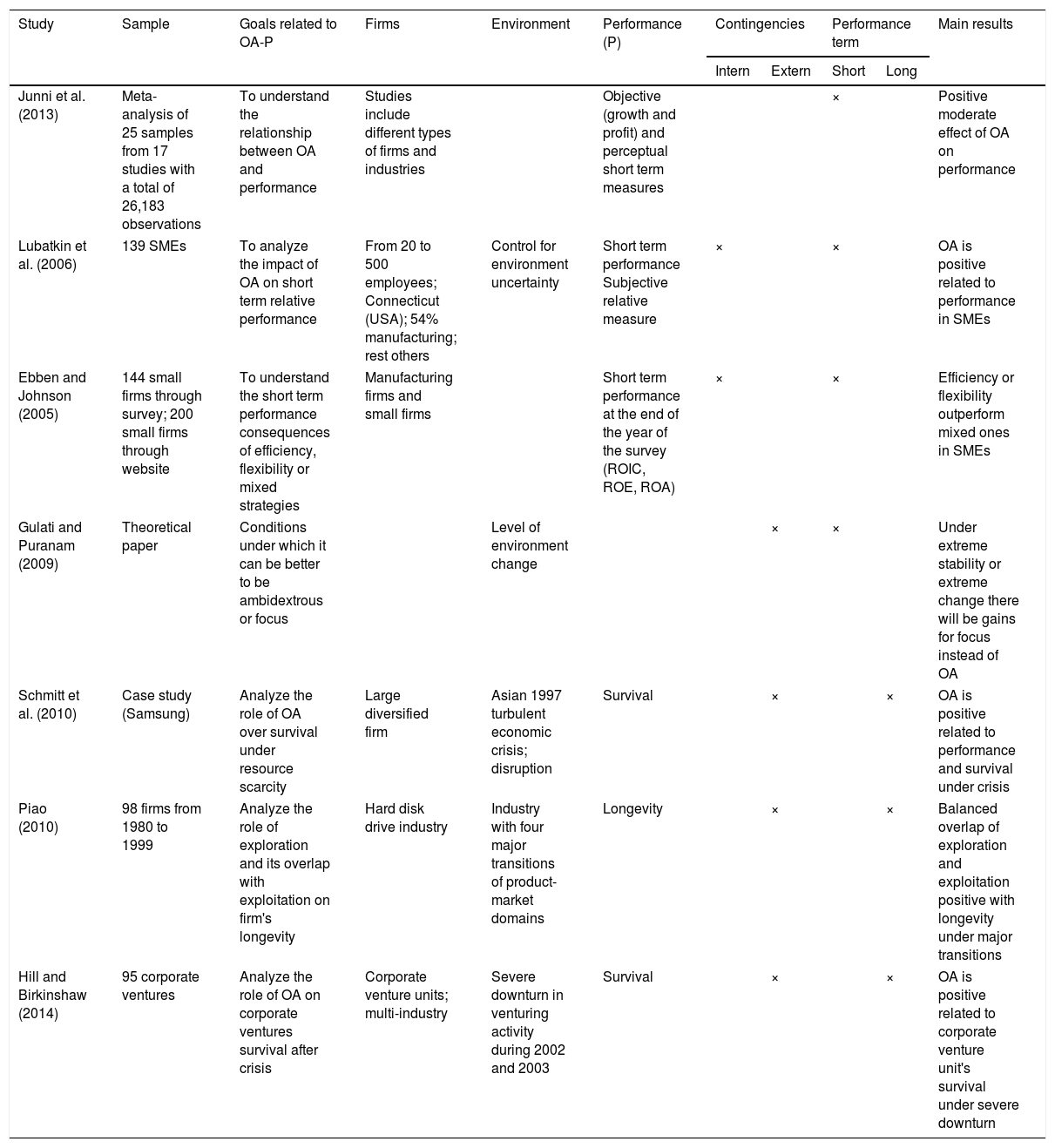

Starting with the overview that the meta-analysis of Junni et al. (2013) offers regarding the relationship between ambidexterity and performance, Table 1 summarizes the studies that link organizational ambidexterity with short-term performance and the internal contingencies of SMEs, or that link organizational ambidexterity with survival under external contingencies offering contradictory results about the ubiquity of ambidexterity under internal and external contingencies of restrictions.

Studies that link SME's organizational ambidexterity (OA), performance and contingencies.

| Study | Sample | Goals related to OA-P | Firms | Environment | Performance (P) | Contingencies | Performance term | Main results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intern | Extern | Short | Long | |||||||

| Junni et al. (2013) | Meta-analysis of 25 samples from 17 studies with a total of 26,183 observations | To understand the relationship between OA and performance | Studies include different types of firms and industries | Objective (growth and profit) and perceptual short term measures | × | Positive moderate effect of OA on performance | ||||

| Lubatkin et al. (2006) | 139 SMEs | To analyze the impact of OA on short term relative performance | From 20 to 500 employees; Connecticut (USA); 54% manufacturing; rest others | Control for environment uncertainty | Short term performance Subjective relative measure | × | × | OA is positive related to performance in SMEs | ||

| Ebben and Johnson (2005) | 144 small firms through survey; 200 small firms through website | To understand the short term performance consequences of efficiency, flexibility or mixed strategies | Manufacturing firms and small firms | Short term performance at the end of the year of the survey (ROIC, ROE, ROA) | × | × | Efficiency or flexibility outperform mixed ones in SMEs | |||

| Gulati and Puranam (2009) | Theoretical paper | Conditions under which it can be better to be ambidextrous or focus | Level of environment change | × | × | Under extreme stability or extreme change there will be gains for focus instead of OA | ||||

| Schmitt et al. (2010) | Case study (Samsung) | Analyze the role of OA over survival under resource scarcity | Large diversified firm | Asian 1997 turbulent economic crisis; disruption | Survival | × | × | OA is positive related to performance and survival under crisis | ||

| Piao (2010) | 98 firms from 1980 to 1999 | Analyze the role of exploration and its overlap with exploitation on firm's longevity | Hard disk drive industry | Industry with four major transitions of product-market domains | Longevity | × | × | Balanced overlap of exploration and exploitation positive with longevity under major transitions | ||

| Hill and Birkinshaw (2014) | 95 corporate ventures | Analyze the role of OA on corporate ventures survival after crisis | Corporate venture units; multi-industry | Severe downturn in venturing activity during 2002 and 2003 | Survival | × | × | OA is positive related to corporate venture unit's survival under severe downturn | ||

In adverse conditions, such as a worldwide economic crisis, survival becomes very complicated for companies, especially SMEs (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2011). For example, bankruptcy in the manufacturing industry in Spain increased by more than 100% in 2008, with rates of growth between 200% and 390% until 2012 compared with data from 2007 (INE, 2017). In this context, survival is an important consideration because it is a necessary condition for SMEs long-term success, and given the mortality rates of these firms, it is not a trivial matter. SMEs have to deal with an important sales decrease, the collapse of profitability or credit rationing, among other problems (Blanco et al., 2016).

As Table 1 shows, previous studies that relate SMEs ambidexterity with short-term performance present contradictory findings. Some studies found a positive relationship between ambidexterity and performance in SMEs (Lubatkin et al., 2006) while others doubt this positive relationship. For instance, Ebben and Johnson (2005) find that small firms benefit less when they try to combine efficiency and flexibility than when they focus on one or the other. Similarly, Voss and Voss (2012) point out that SME managers achieve better performance when they focus on exploitation than when they look for ambidexterity. However, all of this research focuses on short-term financial performance. It seems plausible that as Ebben and Johnson (2005) demonstrate, the configurations of small firms to achieve exploitation or exploration outperform hybrid configurations in short-term performance. When a small firm adapts its processes, its organizational design, its human resource policies and its control and planning systems towards efficiency or towards flexibility, it will obtain advantages and may outperform an ambidextrous SME in the short term. However, does this focus endanger the long-term performance and survival of SMEs when faced with an economic or financial crisis?

We argue that when faced with a huge financial and economic crisis, the goal of SMEs shifts: from increasing short-term performance to ensuring survival. While exploitation will enable a firm to reduce losses through workforce reductions or by improving productivity or reducing unnecessary costs (Schmitt et al., 2010), exploitation alone will not enable a firm to obtain new, diverse and increased sources of revenue. Although exploitation capabilities are needed, exploration may help to overcome inertial answers and will increase the likelihood of aligning the firm with the environment change (Schmitt et al., 2010). SMEs that invest in exploration gain new knowledge, support novel proposals and are capable of applying their knowledge and technologies to new markets and products (Schmitt et al., 2010).

The need for an ambidextrous response capacity is recognized in the literature which analyzes the development of specific strategies for survival, known as turnaround strategies. According to Schmitt and Raisch (2013), the turnaround strategies of retrenchment and recovery are contradictory as well as mutually enabling. In fact, these authors suggest that turnarounds need to involve both retrenchment and recovery, as an initial focus only on retrenchment may decrease the firm's innovation capacity, and restrict or inhibit effective recovery activities. Therefore, firms undergoing turnarounds that are able to initiate retrenchment activities and use their savings for overlapping recovery activities are more likely to survive. Some studies on ambidextrous large firms offer evidence coherent with this statement. Piao (2010) argues that although exploration and exploitation may compete for resources at certain points in time, exploitation can generate resources that can be used for future exploration (Lavie et al., 2010). In order to adapt to environment changes, SMEs need to overlap between exploitation and exploration (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997). To survive, these firms must work to efficiently identify and capture new opportunities in order to prevent organizational inertia and the negative effects of path dependence (Simsek et al., 2009).

Ambidextrous SMEs have developed internal processes and managerial capabilities to deal with exploitation and exploration, to improve efficiency without losing the capability to develop novel, uncertain and innovative ideas, products and processes. As a result, ambidextrous SMEs are more skillful and quicker than exploitative firms at sensing the changes of a financial and economic crisis and are able to seize recovering options, making important and quicker decisions about their financial structure for survival and/or making decisions about reassigning key assets in order not just to retrench but to recover (e.g. looking for new and different markets through internationalization or through launching new products or brands).

In the long term firms may find it necessary to simultaneously engage in exploration and exploitation (Jansen et al., 2006). While in the short-term SMEs may benefit through focusing on exploitation or exploration, this will affect them negatively in the long term. As some studies have shown, a focus on exploitation activities (e.g. efficiency) tends to come at the cost of exploration activities (e.g. innovation), which results in a competency trap. That competency trap, in turn, leads to long-term stagnation and profitability problems (Levinthal and March, 1993; McNamara and Baden-Fuller, 1999; Smith and Tushman, 2005). Similarly, a focus on exploration activities leads to a failure trap because new ideas remain underdeveloped (Levinthal and March, 1993). According to March (1991), the firm's survival over time relies on its ability to exploit existing assets while simultaneously exploring new ideas, as well as on its efficiency, flexibility, adaptability, and alignment. O’Reilly and Tushman (2013: 326) review the evolution of ambidexterity research and conclude that “in uncertain environments, organizational ambidexterity appears to be positively associated with increased firm innovation, better financial performance, and higher survival rates”. In this regard, we suggest the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 4 In an environment of financial and economic crisis, SMEs’ ambidexterity is positively related to survival.

In the selection of the sample, we looked for homogenous industries strongly hit by the international crisis, and with easy access to information on their companies. We used the ORBIS® database3 to discern the relevant population in the focal region (Valencian Community), a mature, Spanish, low-tech, industrial region surrounding the authors’ research center. The severity of the international crisis in the chosen area and in the type of company analyzed (manufacturing firms) has been enormous.4 On the other hand, the manufacturing sector in Spain is one of those with the highest proportion of family businesses (Corona, 2015), which makes it especially attractive for studies that consider this business characteristic. The study population included 814 SMEs with 20 to 250 employees that were active in the manufacturing sector and were not strategic business units of other firms. From July 2009 to May 2010, firms were invited to participate in a national research project on SME governance, strategy, and performance via an omnibus survey (administered questionnaire). Of these organizations, 113 agreed to participate in the survey and provided complete information for this paper, which is a response rate of 13.88%, similar to rates seen in other surveys of top executives in SMEs (e.g., Escribá-Esteve et al.’s [2008] study reports response rates of 6–21%) and the size of the sample is similar to those used in studies of family-firm TMTs (Binacci et al., 2016; Minichilli et al., 2010; Wiersema and Bantel, 1992).

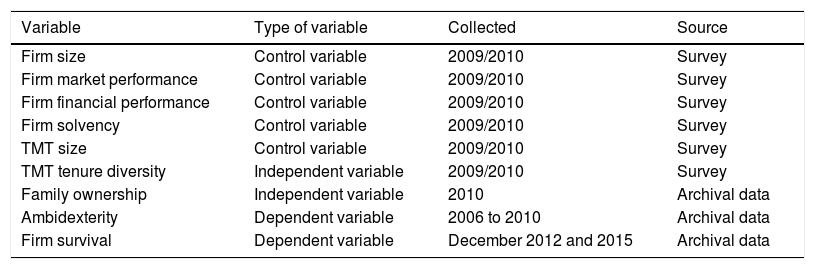

To test our hypotheses, data were collected through the omnibus survey and from archival sources during different periods (see Table 2). To mitigate the potential for common method bias, data on the dependent variables were collected from external sources (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Thus, data on organizational ambidexterity and firm survival were obtained from the ORBIS® database. Family ownership data were collected from the same database because this variable was not included in the omnibus survey. Data on TMT characteristics, firm performance, solvency and size (full-time or equivalent employees) were collected from the survey responses.

Variables and data sources.

| Variable | Type of variable | Collected | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm size | Control variable | 2009/2010 | Survey |

| Firm market performance | Control variable | 2009/2010 | Survey |

| Firm financial performance | Control variable | 2009/2010 | Survey |

| Firm solvency | Control variable | 2009/2010 | Survey |

| TMT size | Control variable | 2009/2010 | Survey |

| TMT tenure diversity | Independent variable | 2009/2010 | Survey |

| Family ownership | Independent variable | 2010 | Archival data |

| Ambidexterity | Dependent variable | 2006 to 2010 | Archival data |

| Firm survival | Dependent variable | December 2012 and 2015 | Archival data |

Our dependent variables are firm survival and organizational ambidexterity. Firm survival is a classic measure of the long-term performance of companies (Friedlander and Pickle, 1968; Gibson et al., 1973; Steers, 1975; Thompson and McEwen, 1958). In general, it is considered to be the ultimate proof of long-term success (Josefy et al., 2017), a test of the permanent adaptation to the business environment (Aldrich, 1979; Hannan and Freeman, 1977; Kanter and Brinkerhoff, 1981), widely used as a dependent variable in studies on change and adaptation (Romanelli and Tushman, 1994). According to Josefy et al. (2017), the literature uses a broad set of terms to refer to organizational survival, including mortality, death, market exit and failure, which are used to reflect a number of meanings such as discontinuation of operations, bankruptcy or discontinuity of ownership. The first meaning of survival (operations dimension) captures the continuation or cessation of a company's activity in a given market environment, as well as being the dimension that drives the definition of firm death or failure more prevalent in the management literature, particularly regarding undiversified firms (Josefy et al., 2017). These authors observe that scholars have studied operationalized survival with various measures of mortality such as market exit, bankruptcy or discontinuation of operations, rather than measures such as number of years a company survived after a baseline or the overall lifespan of a firm. Thus, in our research the classification of survived versus failed firms (coded with 1 and 0, respectively) was based on the classification of the active versus bankruptcy/liquidation status marker of firms from the ORBIS© database. Survived firms were identified based on their active marker, which indicates that they have not experienced an event of failure. The companies that appeared in bankruptcy were classified as failed firms, since the rehabilitation rate of companies in our focal area which have filed for bankruptcy is less than 6% according to national statistics. The companies that appeared as liquidated or in liquidation were marked as failed. On the other hand, we verified that no company ceased its activity because another company acquired it. The measurement of the active status was made in two different moments of time: December 31, 2012 and December 31, 2015, which is just before the end of the international crisis and two and a half years after the crisis had passed. The first year (i.e. 2012) ended with 72.57% of active companies, and the second year (2015) with 69.91%. All companies were active at the time of data collection via questionnaire (May 2009–May 2010).

In order to increase the robustness of our findings, we also report our main analyses using the bankruptcy probability of a company at the end of 2012 and 2015 as criterion variable, measured with the Altman Z-score for private firms, a procedure previously used for model bankruptcy and financial distress in SMEs (Altman and Sabato, 2007; McGuinness et al., 2018). Distress was modeled as a binary choice equal to 0 if a firm was classified as distressed using the Z-score cut-off (1.23), and equal to 1 otherwise.

Organizational ambidexterity acts as a dependent and independent variable. It was measured as an aggregation (sum) of standardized indicators of exploitation and exploration (see Lubatkin et al. (2006) for a similar aggregation approach). We used objective data obtained from secondary sources in order to reduce bias in the exploration/exploitation data (Sarkees et al., 2014). A fundamental dimension of exploitation is the search for efficiency, which usually uses as a proxy labor-cost reduction (Moon and Yim, 2014). Thus, we measured exploitation using the ratio of total labor costs to total sales, which is a common labor-efficiency ratio. Exploration was measured as the number of patents obtained (Sarkees et al., 2014) and the number of new brands, as these two variables are associated with the creation of new products (Tollin and Schmidt, 2015), especially in manufacturing SMEs. In all the variables we averaged the five-year data (2006–2010) in order to capture a solid orientation in each one of them.

In terms of the independent variables, we followed the specialized literature (Camelo-Ordaz et al., 2005; Fernández-Mesa et al., 2013; Jaw and Lin, 2009) that measures diversity using the coefficient of variation (standard deviation divided by the average) for the tenures of TMT members at the firm. We measured age diversity as proxy of tenure diversity in a career, and seniority in the firm as proxy of tenure in a position. The TMT tenure diversity variable was constructed as the sum of the standardized coefficients of variation of the seniority and age variables. Higher figures indicate greater tenure diversity. Finally, to measure family ownership, we adopted an objective ownership measure based on the percentage of ownership held by a single family. In order to unambiguously capture the owners’ ability to exercise control, the variable took a value of 1 when family members owned or controlled at least 51% of the voting stock (84.96% of the companies in the sample) and a value of 0 when the stake held by family members was less than 51% (Binacci et al., 2016; Ibrahim et al., 2009; Van Der Merwe, 2009).

We also included control variables. As in other research on ambidexterity and on firm survival and failure (e.g., Cao et al., 2010; Haveman, 1993; Heavey and Simsek, 2014; Jansen et al., 2008; Lubatkin et al., 2006; Pertusa-Ortega and Molina-Azorín, 2018; Thornhill and Amit, 2003), we controlled for TMT size, firm size (natural log of employees), firm market (sales and market share), financial (ROI) performance, and firm solvency. All of these variables were captured through a questionnaire. The measures of performance and solvency have been obtained from a 5-points Likert scale where 1=“much worse than my competitors”, 3=“equal to my competitors”, and 5=“much higher than my competitors”. The market performance is constructed as an average of the Likert scales for sales and market share. Table 2 shows the variables of the study along with its sources and when they were obtained.

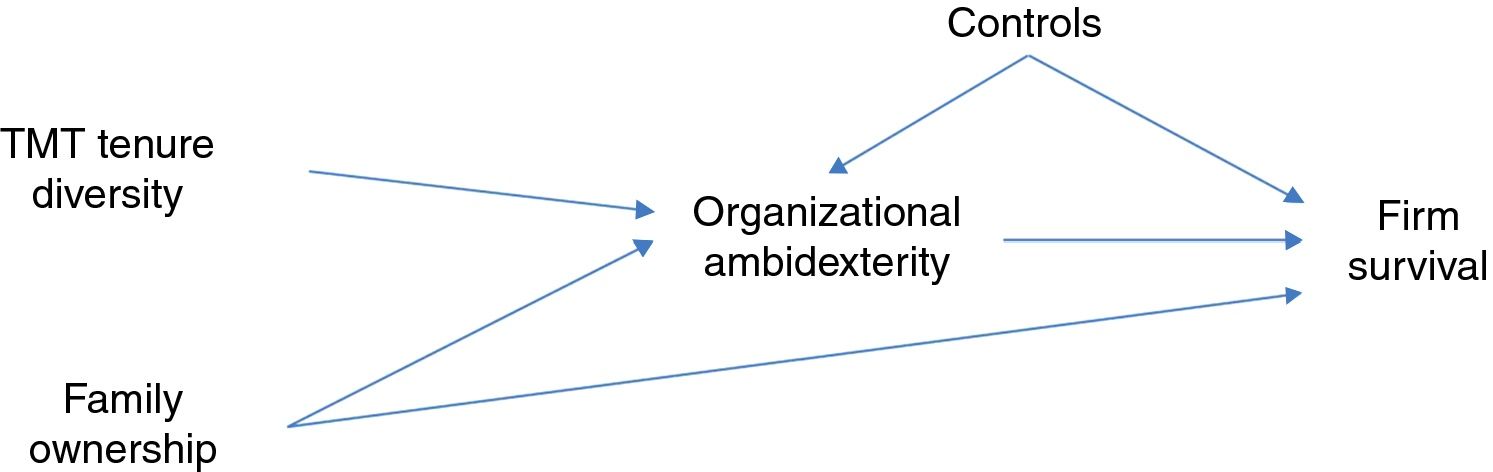

Analyses and resultsGiven the existence of two dependent variables, we estimated the whole model by applying structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques, using the maximum likelihood method. In addition, in order to perform additional statistical tests, we estimated the partial models, one for each dependent variable, using OLS for ambidexterity and binary logistic regression for firm survival. The full model shown in Fig. 1 indicates the theoretical relations taken from our study of the literature; Tables 3 and 4 provide the descriptive statistics and the path-analysis results (SEM); and Tables 5 and 6 show the results for the partial models.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Firm survival (active 2012) | .73 | .45 | |||||||||||

| 2. | Firm survival (active 2015) | .70 | .46 | .81 | ||||||||||

| 3. | Firm survival (2012 Altman Z-score) | .58 | .50 | .65 | .66 | |||||||||

| 4. | Firm survival (2015 Altman Z-score) | .56 | .50 | .65 | .74 | .80 | ||||||||

| 5. | Ambidexterity | .01 | 1.90 | .29 | .27 | .25 | .31 | |||||||

| 6. | Firm size (ln) | 3.58 | .82 | .00 | .03 | .15 | .08 | . 37 | ||||||

| 7. | Market performance | 3.08 | .59 | .15 | .13 | .12 | .06 | .29 | .25 | |||||

| 8. | Financial performance | 3.11 | .55 | .23 | .23 | .29 | .24 | .30 | .25 | .52 | ||||

| 9. | Firm solvency | 3.42 | .78 | .31 | .33 | .48 | .31 | .23 | .23 | .38 | .57 | |||

| 10. | TMT size | 3.63 | 1.42 | .11 | .13 | .02 | .09 | .31 | .50 | .09 | .20 | .06 | ||

| 11. | TMT tenure diversity | .00 | .87 | .00 | .07 | −.04 | .03 | .24 | .12 | .08 | .01 | −.11 | .43 | |

| 12. | Family ownership | .85 | .36 | .07 | .10 | .10 | .07 | −.26 | −.09 | −.12 | −.21 | −.20 | −.16 | .05 |

Notes: N=113. All correlations higher than |.19| are significant at the .05 level.

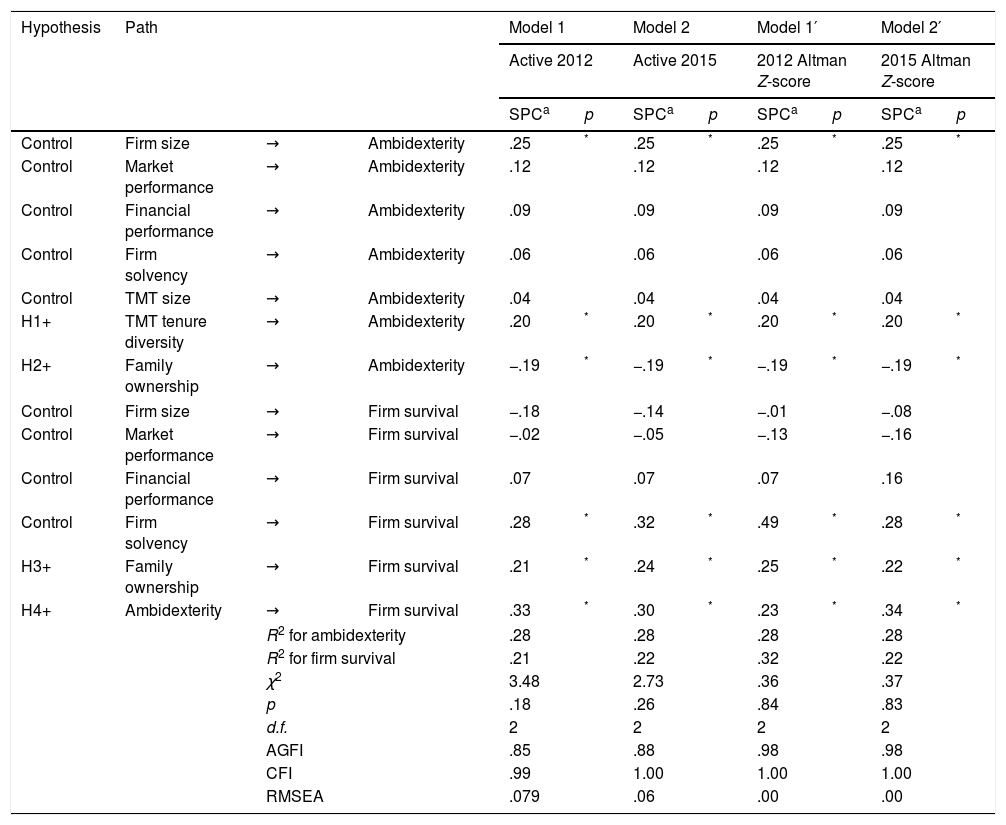

Structural model results.

| Hypothesis | Path | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1′ | Model 2′ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active 2012 | Active 2015 | 2012 Altman Z-score | 2015 Altman Z-score | ||||||||

| SPCa | p | SPCa | p | SPCa | p | SPCa | p | ||||

| Control | Firm size | → | Ambidexterity | .25 | * | .25 | * | .25 | * | .25 | * |

| Control | Market performance | → | Ambidexterity | .12 | .12 | .12 | .12 | ||||

| Control | Financial performance | → | Ambidexterity | .09 | .09 | .09 | .09 | ||||

| Control | Firm solvency | → | Ambidexterity | .06 | .06 | .06 | .06 | ||||

| Control | TMT size | → | Ambidexterity | .04 | .04 | .04 | .04 | ||||

| H1+ | TMT tenure diversity | → | Ambidexterity | .20 | * | .20 | * | .20 | * | .20 | * |

| H2+ | Family ownership | → | Ambidexterity | −.19 | * | −.19 | * | −.19 | * | −.19 | * |

| Control | Firm size | → | Firm survival | −.18 | −.14 | −.01 | −.08 | ||||

| Control | Market performance | → | Firm survival | −.02 | −.05 | −.13 | −.16 | ||||

| Control | Financial performance | → | Firm survival | .07 | .07 | .07 | .16 | ||||

| Control | Firm solvency | → | Firm survival | .28 | * | .32 | * | .49 | * | .28 | * |

| H3+ | Family ownership | → | Firm survival | .21 | * | .24 | * | .25 | * | .22 | * |

| H4+ | Ambidexterity | → | Firm survival | .33 | * | .30 | * | .23 | * | .34 | * |

| R2 for ambidexterity | .28 | .28 | .28 | .28 | |||||||

| R2 for firm survival | .21 | .22 | .32 | .22 | |||||||

| χ2 | 3.48 | 2.73 | .36 | .37 | |||||||

| p | .18 | .26 | .84 | .83 | |||||||

| d.f. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| AGFI | .85 | .88 | .98 | .98 | |||||||

| CFI | .99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| RMSEA | .079 | .06 | .00 | .00 | |||||||

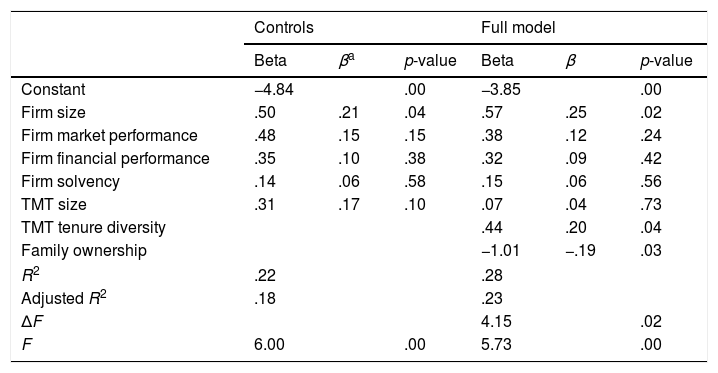

Study of ambidexterity as a dependent variable via ordinary least squares.

| Controls | Full model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | βa | p-value | Beta | β | p-value | |

| Constant | −4.84 | .00 | −3.85 | .00 | ||

| Firm size | .50 | .21 | .04 | .57 | .25 | .02 |

| Firm market performance | .48 | .15 | .15 | .38 | .12 | .24 |

| Firm financial performance | .35 | .10 | .38 | .32 | .09 | .42 |

| Firm solvency | .14 | .06 | .58 | .15 | .06 | .56 |

| TMT size | .31 | .17 | .10 | .07 | .04 | .73 |

| TMT tenure diversity | .44 | .20 | .04 | |||

| Family ownership | −1.01 | −.19 | .03 | |||

| R2 | .22 | .28 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | .18 | .23 | ||||

| ΔF | 4.15 | .02 | ||||

| F | 6.00 | .00 | 5.73 | .00 | ||

Notes: N=113. Maximum VIF=1.85.

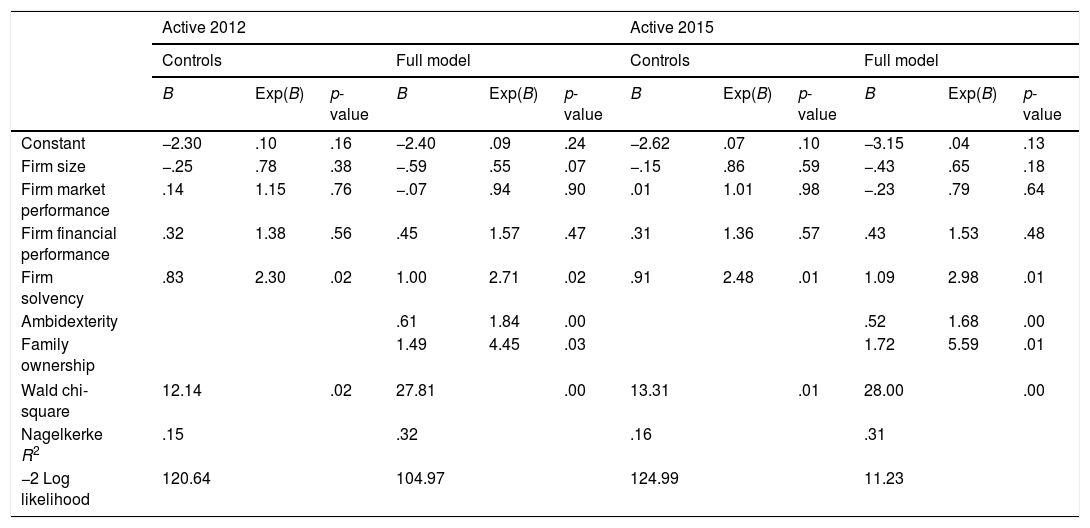

Study of firm survival as a dependent variable via binary logistic regression.

| Active 2012 | Active 2015 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Full model | Controls | Full model | |||||||||

| B | Exp(B) | p-value | B | Exp(B) | p-value | B | Exp(B) | p-value | B | Exp(B) | p-value | |

| Constant | −2.30 | .10 | .16 | −2.40 | .09 | .24 | −2.62 | .07 | .10 | −3.15 | .04 | .13 |

| Firm size | −.25 | .78 | .38 | −.59 | .55 | .07 | −.15 | .86 | .59 | −.43 | .65 | .18 |

| Firm market performance | .14 | 1.15 | .76 | −.07 | .94 | .90 | .01 | 1.01 | .98 | −.23 | .79 | .64 |

| Firm financial performance | .32 | 1.38 | .56 | .45 | 1.57 | .47 | .31 | 1.36 | .57 | .43 | 1.53 | .48 |

| Firm solvency | .83 | 2.30 | .02 | 1.00 | 2.71 | .02 | .91 | 2.48 | .01 | 1.09 | 2.98 | .01 |

| Ambidexterity | .61 | 1.84 | .00 | .52 | 1.68 | .00 | ||||||

| Family ownership | 1.49 | 4.45 | .03 | 1.72 | 5.59 | .01 | ||||||

| Wald chi-square | 12.14 | .02 | 27.81 | .00 | 13.31 | .01 | 28.00 | .00 | ||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .15 | .32 | .16 | .31 | ||||||||

| −2 Log likelihood | 120.64 | 104.97 | 124.99 | 11.23 | ||||||||

| 2012 Altman Z-score | 2015 Altman Z-score | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Full model | Controls | Full model | |||||||||

| B | Exp(B) | p-value | B | Exp(B) | p-value | B | Exp(B) | p-value | B | Exp(B) | p-value | |

| Constant | −5.48 | .00 | .00 | −7.83 | .00 | .00 | −3.04 | .05 | .05 | −3.37 | .03 | .09 |

| Firm size | .23 | 1.26 | .45 | .10 | 1.10 | .77 | .06 | 1.06 | .82 | −.19 | .82 | .52 |

| Firm market performance | −.47 | .63 | .33 | −.81 | .44 | .13 | −.46 | .63 | .29 | −.73 | .48 | .12 |

| Firm financial performance | .38 | 1.46 | .49 | .60 | 1.82 | .33 | .60 | 1.82 | .24 | .69 | 2.00 | .22 |

| Firm solvency | 1.56 | 4.76 | .00 | 1.94 | 6.93 | .00 | .77 | 2.15 | .02 | .92 | 2.50 | .01 |

| Ambidexterity | .40 | 1.49 | .01 | .50 | 1.64 | .00 | ||||||

| Family ownership | 2.33 | 1.33 | .00 | 1.60 | 4.95 | .02 | ||||||

| Wald chi-square | 3.44 | .00 | 44.58 | .00 | 13.17 | .01 | 29.00 | .00 | ||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .32 | .44 | .15 | .30 | ||||||||

| −2 Log likelihood | 123.00 | 108.86 | 141.98 | 126.15 | ||||||||

Note: N=113.

None of the correlation coefficients or computed variance inflation factors suggest potential problems of multicollinearity. To control for endogeneity, we studied the correlation between the independent variables and the error term of the regression models and we can conclude that there is no endogeneity problem in our study (Bascle, 2008; Hamilton and Nickerson, 2003).

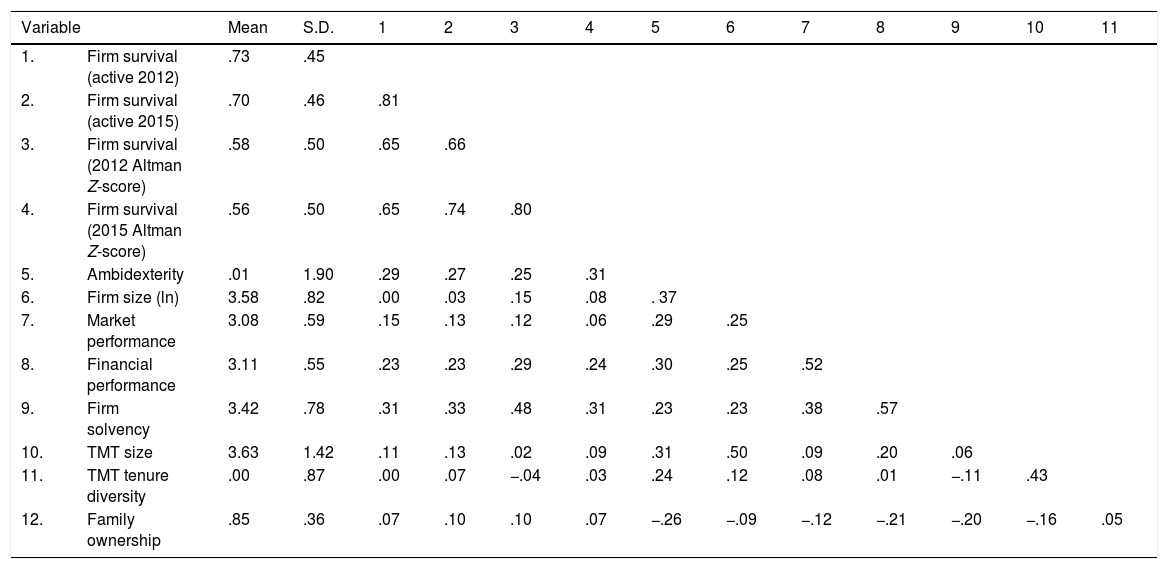

Table 3 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables included in our analyses. Table 4 reports the structural model results obtained from path analysis using AMOS/SPSS® software. In this table we present the results of four models which test the relationships shown in Fig. 1. Models 1 and 2 introduce ambidexterity and firm survival as dependent variables. The firm survival variable took a value of 1 if a firm was active or 0 if it was not active in two different moments of time: December 31, 2012 and December 31, 2015. Models 1′ and 2′ change the firm survival measurement from active status to the Altman Z-score, an indicator that predicts bankruptcy. These models are reported as additional tests to verify the robustness of the empirical study. All models fit the data, with non-significant χ2 and goodness fit indicators within the usual parameters required by the literature. Moreover, these models have good predictive capacity, as the R2 observed are high for the dependent variables (28% for ambidexterity and from 21% to 32% for firm survival).

Our results support the hypotheses of this study (Table 4). Hypothesis 1, which states that tenure diversity in TMTs has a positive effect on ambidexterity, is positive and statistically significant (β=.20, p<.05), as predicted. Hypothesis 2 proposes that family ownership is negatively related to ambidexterity. The effect is negative and statistically significant (β=−.19, p<.05), as expected. Hypothesis 3, which suggests that family ownership has a positive effect on a firm's survival, is robustly supported in all the models (β∈[.21, .25], p<.05). Hypothesis 4 states that ambidexterity is positively related to a firm's survival and is strongly supported in the four models studied (β∈[.19, .33], p<.05). Regarding the control variables, firm size and firm solvency do appear to be predictors of ambidexterity and a firm's survival, respectively.

Tables 5 and 6 present additional statistical tests for the partial models in which we only consider one dependent variable. Table 5 summarizes the study of ambidexterity as a dependent variable via ordinary least squares. We show two models, one that includes only the control variables, and another one that includes control and independent variables. The full model is significant, with a high R2, which significantly exceeds the adjusted R2 of the model of controls; the independent variables (TMT tenure diversity and family ownership) are significant and have the predicted direction. These results are consistent with our path analysis reported in Table 4.

Table 6 shows the study of firm survival as a dependent variable via binary logistic regression. Four groups of models are shown. The first two measure survival with a dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 if the company was active in 2012 and in 2015. If it was not active (dissolved or bankrupt), the variable takes the value of zero. The two groups of models first present the regression with the control variables and then the regression with all the modeled variables. In both cases we can observe that when the independent variables entered into the regression the adjusted R2 increased significantly, with its coefficients also significant and with the expected direction.

The remaining two groups of models measure survival with the Altman Z-score for private firms. Survival is modeled as a binary choice equal to zero if a firm was classified as distressed using the Z-score cut-off (1.23), and equal to 1 otherwise. As done previously, the two groups of models first present the regression with the control variables and then the full model regression. We can also observe here that when the independent variables entered into the regression the adjusted R2 increased significantly, with their coefficients being significant and with the expected direction. Therefore, the results reported in Table 6 are consistent with our path analysis reported in Table 4. Table 7 shows the summary of the tests performed.

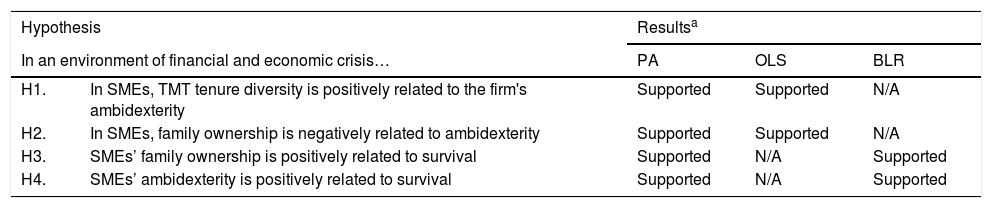

Results of hypothesis testing.

| Hypothesis | Resultsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In an environment of financial and economic crisis… | PA | OLS | BLR | |

| H1. | In SMEs, TMT tenure diversity is positively related to the firm's ambidexterity | Supported | Supported | N/A |

| H2. | In SMEs, family ownership is negatively related to ambidexterity | Supported | Supported | N/A |

| H3. | SMEs’ family ownership is positively related to survival | Supported | N/A | Supported |

| H4. | SMEs’ ambidexterity is positively related to survival | Supported | N/A | Supported |

Although our data are limited to SME manufacturing firms, our findings are in line with other results in the literature on ambidexterity in which there is a positive and significant relationship between this variable and different performance measures. According to the meta-analysis carried out by Junni et al. (2013), studies that focused on service industries, manufacturing industries or several different industries reported a significant positive ambidexterity–performance relationship. These authors found that ambidexterity is less important in manufacturing than in service and high-technology sectors due to the influence of environmental dynamism. Therefore, our results can be generalized to other industries where the level of dynamism of the environment is at least equal to or higher than manufacturing industries.

The sample companies are Spanish, and it could be questioned whether they differ from other countries’ companies in variables such as family character or the survival rate. According to the OECD (2018), the ‘enterprise death rate’ for Spain ranged between 8.2% and 9.8% during the period of 2011 and 2015, with an average of 9.0%. In Europe, according to the same source, the average for those years was 8.9%, very similar to the Spanish rate. Furthermore, according to Corona (2015), 88.8% of businesses in Spain are family firms (79.5% if micro firms are excluded), a figure that is very similar to the European average of 85% according to 2014 Ernst & Young's Family Firms Yearbook (Niebler, 2014). In addition, this percentage is very similar to the share of companies that we have considered in our sample as controlled by the family (84.96%).

All of this provides external validity to our Spanish findings.

Discussion and conclusionsThe primary purpose of this paper was to highlight the importance of ambidexterity for SMEs’ survival after an external financial and economic crisis. Previous studies have consistently pointed to the positive effect of ambidexterity on the short-term financial performance of large firms (see Junni et al., 2013, for a meta-analysis), while casting doubts on the positive or negative consequences of ambidexterity for SMEs’ short-term performance (Ebben and Johnson, 2005; Gulati and Puranam, 2009; Lubatkin et al., 2006). Additionally, this inconclusive evidence generally links the focus or ambidexterity of SMEs with financial short-term performance, thereby adopting a simplistic interpretation of the relationship between short-term performance and survival (Hughes, 2018). The better the former the greater the likelihood of the latter. This stands in contrast to the theoretical arguments of March (1991) and the idea of competency trap (Levinthal and March, 1993; McNamara and Baden-Fuller, 1999; Smith and Tushman, 2005).

Ambidexterity has received notable attention among scholars because it tries to answer the fundamental question of how organizations survive in the face of change. The underlying idea that some firms are able to jump over the trade-offs of exploration and exploitation and be dexterous in both is, undoubtedly, theoretically attractive.

Research contributionsWe contribute to the above mentioned line of research arguing that, under some conditions that may raise doubts about its ubiquity, ambidexterity enables survival. Specifically, when firms face an environment of external restrictions with the internal disadvantages that SMEs have, there are theoretical doubts about the beneficial impact of ambidexterity. Financial crises pose threats to SMEs’ solvency and reduce their likelihood to access bank finance. In addition, severe economic crises lead to decreases in demand, the recommended solutions focusing on productivity, retrenchment and efficiency improvements. However, we argue that under financial distress, ambidextrous SMEs are more skillful and quicker than exploitative firms at sensing changes and are able to seize opportunities to help recovery and maintain efficiency. They are also able to make important decisions quicker about their financial structure for survival as well as decisions about reassigning key assets so as not only retrench but also recover (e.g. looking for new and different markets through launching new products or new brands or through internationalization). This contribution is in line with understanding ambidexterity as a dynamic capability (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2008) and with the advice of turnaround researchers (Schmitt and Raisch, 2013).

Additionally, our study provides an empirical contribution to the study of the relationship between ambidexterity and survival, contributing to the scarce studies on this subject. In this sense, empirical conditions for analyzing general environment changes are not easily found – apart from a specific industry or firm; and therefore conditions for testing the link between ambidexterity and survival are not usual. It is perhaps for these reasons that empirical studies which link ambidexterity with survival have been scarce and focus on specific industries subject to changing technological environments or on case studies (Piao, 2010; Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996; Schmitt et al., 2010). The financial and economic crisis provides a unique context of high bankruptcy rates (INE, 2017). This environment provides novel empirical evidence of the role of ambidexterity in the survival of SMEs. Our work offers robust evidence of the relevance of ambidexterity for survival under a context of internal disadvantages and scarce resources (SMEs) and in the context of an extensive external economic and financial crisis (McGuinness et al., 2018). Our study finds evidence that ambidexterity does increase the likelihood of survival, measured through the Altman Z-score or measured through mortality, at the end of the financial and economic crisis and in the period of recovery. In addition, our findings are coherent with the scarce evidence available on ambidexterity and survival. Piao (2010) demonstrated that an overlap between exploration and exploitation increased the likelihood of survival among 64 large firms in the hard-disk industry. Tushman and O’Reilly (1996) and Schmitt et al. (2010) found similar patterns in their case studies of large firms. In addition, our results seem consistent with the literature on turnarounds. This stream of literature suggests that, in times of crisis, firms need a balance between activities that increase efficiency and improve resources (known as retrenchment activities), and those focused on innovation or recovery (Schmitt and Raisch, 2013).

Our study also contributes to our understanding of the antecedents of SMEs’ ambidexterity by providing a theoretical model that offers an extended view of the upper-echelons theory, combining the role of managers with those found in family-firm research. In this regard, it opens a new line of inquiry, and suggests a need to consider variables related to the effects of ownership characteristics and the main skills of top managers in decision making in SMEs. In that sense, we follow the line of research that views ambidexterity as a dynamic capability and assigns upper echelons a key role in its development through sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring. On the one hand, the corporate elite may have a greater impact on the behavior and actions of SMEs than senior managers in larger firms characterized by extensive hierarchical and administrative systems (Lubatkin et al., 2006). On the other hand, in SMEs an extended view of upper echelons including top managers and owners will be more accurate for explaining a firm's sensing, seizing and transforming.

In addition, our study offers empirical evidence that upper echelons play a key role in ensuring ambidexterity in SMEs. Our findings extend evidence from earlier studies on the role of upper echelons in the development and use of ambidexterity under severe environment conditions, such as a study by Schmitt et al. (2010) on Samsung Electronics. More specifically, we find evidence that tenure diversity in the TMT affects ambidexterity. Our results support the idea that tenure diversity provides a range of perspectives, as members of tenure-diverse teams have had different experiences and different socialization processes. Homogeneous points of view in decision making are a common feature in SMEs, an aspect that is even more pronounced in family-owned SMEs due to the family's shared roots, values, and beliefs (Webb et al., 2010). This makes it difficult to enrich the information that these firms have and to view it through different prisms. Therefore, tenure diversity in the TMT can be beneficial from a decision-making perspective (Minichilli et al., 2010; Nielsen, 2010), as it can decrease the tendency to engage in groupthink (Milliken and Martins, 1996; Simons et al., 1999). Tenure diversity can also affect the team's desire to accept risk because older members of the TMT tend to be more risk averse than younger members. This proposal is in line with studies which show the influence of age heterogeneity on proactive behaviors and risk taking (Escribá-Esteve et al., 2008; Wiersema and Bantel, 1992).

The role of family ownership in SME ambidexterity and survival is complex. In line with our expectations, we found a negative relationship between family ownership and ambidexterity in SMEs. This suggests that these firms respond to external financial and economic crises by focusing on efficiency and avoiding ambidexterity. These results coincide with the empirical evidence that links family ownership negatively with innovation in large public firms (Block et al., 2013; Filser et al., 2018; Muñoz-Bullón and Sánchez-Bueno, 2011). Firms tend to favor exploitation over exploration due to the greater certainty of its reward (March, 1991) and, in light of our evidence, this tendency seems to be stronger in family-owned firms. Our results are coherent with the vision of family-owned firms as being conservative and tending to avoid decisions that may increase risk and uncertainty such as innovation investments (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2010; König et al., 2013), and are also coherent with the SEW arguments that loss aversion is a feature of family-owned firms (Berrone et al., 2012; Chrisman and Patel, 2012). In a recent study, Hughes et al. (2017) state that different configurations of exploration and exploitation appear under different degrees of family influence. Moreover, these configurations are related to family firm performance. Hughes et al. (2017: 11) state that: “as general findings, we identify multiple configurational paths to superior family firm performance. The only construct consistent across all paths is exploitation. Exploitation is therefore a key ingredient in family firm performance”.

On the other hand, the results suggest another side of family ownership regarding SMEs, i.e. the positive direct effect of family ownership on survival. One explanation comes from a line of research that points to the specific sources of financial resources for family-owned firms under an economic and financial crisis (Crespí and Martín-Oliver, 2015). Based on agency cost arguments, they state that a lender will perceive that their interests coincide more with the ones of the family firm, providing better conditions in the loan contract. Additionally, the strong solid relations built during periods of expansion with stakeholders could reduce the agency costs and diminish the lenders’ perceptions of risk regarding family firms (Crespí and Martín-Oliver, 2015). Additionally, in our study family property is defined by the concentration of 51% or more of the shares in the hands of a family. This may imply a strong link between the wealth of the family and that of the firm. As a consequence, given the strong commitment of the owing family, under an environment with huge increases in the risk of bankruptcy, they may try to avoid the financial losses and family losses that bankruptcy implies. Bankruptcy (or the risk of it) will imply losses for the family's name and patrimony, and reduce the likelihood of succession. With respect to these risks, our study found evidence that family-owned firms will take actions that preserve their SEW (Berrone et al., 2012) in coherence with loss aversion arguments (Chrisman and Patel, 2012) providing a context of complementarity of financial and non-financial goals in family-owned firms (Chua et al., 2018).

Managerial implicationsOur study has some practical implications. For managers of SMEs, our paper shows that ambidexterity is relevant for organizational survival. This highlights a difficult challenge for managers, who need to improve efficiency in downturns, and use part of the resulting savings for activities related to innovation and exploration. Survival rates are generally low for SMEs, but an ability to simultaneously achieve efficiency and change clearly improves the odds of survival.

In our study we found evidence of the relationship between ambidexterity and survival for two specific sources of exploration related to entering new markets and/or marketing new products – by means of increasing the number of patents and/or brands of the SMEs. However, SMEs may have additional sources for becoming ambidextrous by exploring through internationalization or non-technological innovation.

Large and small firms tend to favor exploitation over creating conditions for opportunities to experiment with new possibilities (March, 2006). Large firms may dispose of different alternatives for creating those conditions, e.g. separate structural units (Birkinshaw and Gupta, 2013) that are not available for SMEs. Our study reveals that for SMEs, upper echelons tenure diversity may offer conditions which increase ambidexterity. The tendency of SMEs to centralize decision making at the level of the CEO without developing upper echelon teams may provide these firms with quicker answers but not with better ones which demand diversity for information seeking and novelty. SMEs tend to have a centralized apex and very narrow teams. In such contexts, our study suggests that teams should be composed in a way that enables divergent thinking, consideration of diverse perspectives, and acceptance of new sources of information. In many companies, this can be ensured by increasing the TMT size. These elements, in turn, can enrich decision making. Such diversity might be more relevant for family-owned firms, as they tend to focus more on efficiency.

The solvency of the company emerges as a clear predictor of ambidexterity and survival. Ambidexterity requires sufficient resource slack to maintain investment in exploration and exploration projects. Vermoesen et al. (2013) have shown that SMEs with a large proportion of long-term debt maturing at the start of the recent international crisis had difficulties to renew their loans due to the negative credit supply shock, and hence could invest less during the crisis. On the other hand, countless studies have linked a firm's solvency with a firm's survival. Among the most recent, Guariglia et al. (2016) show that bank-dependent firms had less chance of survival during the recent international crisis. Therefore, it seems clear that raising the level of a firm's solvency in ‘good times’, e.g. resorting to self-financing, is key to maintaining ambidextrous levels in ‘bad times’, and to have sufficient resources to prevent company bankruptcy. In our study, the companies with family ownership are less solvent. However, the family ownership variable is a clear predictor of survival. One potential explanation for this surprising result is that family businesses complement the solvency of the company with the solvency of the family (e.g. through the ‘family office’). But we could not verify if there were several families that controlled the company with a clear shareholder leader or not. Therefore, it could be suggested that a strong company-family identity is a useful complement to business solvency usually measured by the equity/debt ratio.