More than 15 years ago, the organization that accredits physician education in the United States introduced 6 competencies relevant to medical practice. The next phase of this effort resulted in the development of educational milestones based on the competencies to focus the assessment of physicians in training on dimensions of performance critical to good medical practice. This article summarizes the competency-based approach to the education and assessment of US physicians in training, and the shift in the accreditation of physician training programs from a focus on structure and process to an emphasis on educational outcomes.

The milestones were developed through expert consensus in each specialty that established a set of competencies, and a 5-level developmental framework that described the developmental steps in their acquisition from novice to expert/master. The work was informed by the literature, specialty curricula, stakeholder review, and initial testing.

By basing learner assessment on dimensions of performance relevant in the practice of medicine, the milestones produce feedback that is more meaningful to learners, and concurrently base the accreditation of programs on real educational outcomes, contrasted with other attributes that are less directly related to the performance capabilities of graduates.

The development of the milestones and initial testing by communities of practice in internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery, emergency medicine, neurological surgery and urology establishes the initial validity argument for the milestones. Further validity evidence will require study of the value of the milestones in assessment and accreditation, and linking educational outcomes to the performance and clinical outcomes of physicians in practice.

Hace más de 15 años, la organización que acredita la educación médica en Estados Unidos introdujo seis aptitudes relevantes para la práctica médica. La fase siguiente de este proceso dio lugar al desarrollo de hitos educativos basados en las aptitudes, para centrar la evaluación de los médicos en formación en dimensiones de desempeño cruciales para una buena práctica médica. En este artículo se resume el enfoque basado en aptitudes para la educación y evaluación de médicos estadounidenses en formación, y el paso de un enfoque en la estructura y el proceso al énfasis en los resultados educativos en la acreditación de los programas de formación médica.

Los hitos se elaboraron mediante el consenso de expertos en cada especialidad, que establecieron un conjunto de aptitudes, y un marco de desarrollo de cinco niveles, que describió las fases de desarrollo en su adquisición desde el nivel principiante hasta el experto/maestro. El trabajo se documentó a partir de la bibliografía, en concreto planes de estudio de especialidades, revisión de los interesados y pruebas iniciales.

Al basar la evaluación de los estudiantes en dimensiones de desempeño relevantes en la práctica médica, los hitos producen una retroalimentación que es más significativa para los estudiantes, y a la vez basan la acreditación de programas en resultados educativos reales, en contraposición a otras cualidades menos relacionadas con el potencial de desempeño de los graduados.

El desarrollo de los hitos y de las pruebas iniciales por comunidades de práctica en medicina interna, pediatría, cirugía, medicina de urgencias, neurocirugía y urología establece el argumento de validez inicial para los hitos. Para obtener más pruebas de la validez habrá que estudiar el valor de los hitos en evaluación y acreditación, y también relacionar los resultados educativos con el desempeño y los resultados clínicos de los médicos en la práctica.

In the United States, the formal phase of physician training after medical school is called graduate medical education, and consists of three to seven years of formal education in a medical, surgical, or hospital-based specialty. This may be followed by additional advanced fellowship training. Private organizations play an important role in ensuring the quality of medical education and practice by accrediting the formal education and continuing professional development of physicians throughout their career.1 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) is the independent, not for profit corporate organization that accredits physicians’ graduate training. It accredits more than 9,500 allopathic residency and fellowship programs that collectively train more than 117,000 residents and fellows, and the approximately 700 institutions that sponsor accredited programs. ACGME accreditation is recognized by the all physician licensing entities, and the federal government for reimbursement of the costs of resident education, and completion of an accredited residency program is required for candidates to be eligible to take the initial certification examination by the member boards of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).2

The development of the competencies and the educational milestonesIn 1999, recognizing that the predominant focus on medical knowledge and clinical skills underemphasized other relevant areas, the ACGME and the ABMS developed a broader approach to defining the skills and attributes physicians should develop during their formal training and further refine in practice, with a focus on the set of physician attributes important to delivering high-quality are.3,4 At the core of this effort are six competencies relevant to modern medical practice: 1) patient care, 2) medical knowledge, 3) interpersonal and communication skills, 4) professionalism, 5) practice-based learning and improvement (PBLI), and 6) system-based practice (SBP).

The first phase of the shift to accreditation of US graduate medical education programs based on educational outcomes was called the Outcome Project. The goal was to ensure that the formal training and ongoing professional development of physician for US practice would focus on attributes highly relevant to good medical practice, with a vision of basing the accreditation of physician education programs on the educational outcomes attained by their graduates. For the formal phase of physician training, the aim was to shift of the focus of accreditation from programs’ structure and learning processes, to an emphasis of the educational outcomes of individuals who completed graduate medical education. Concurrently, the ABMS member certifying boards began to use the competencies in their expectations for initial certification, and developed expectations for maintenance of certification based on the six competencies.5 For the ongoing maintenance of competency for physicians in practice, this placed greater weight in on professional development in areas relevant to the practice and in need of improvement for the individual physician, with the competency of practice based learning and improvement at the core of the maintenance of certification process.6

Over the first decade of the new millennium, the focus on the competencies through the outcome project resulted in improvements in teaching and assessment. Yet the move toward accreditation based on educational outcomes stagnated. Reasons included a lack of clear definitions of the steps that led to attainment of a given competency, the clinical community's sense that the generic language of the competencies underemphasized key dimensions of physician competence important to practice in a clinical specialty, and the shift in focus by the community and the ACGME to new common duty hour limits for all US residency education programs instituted in July 2003.7 In addition, an accreditation process still largely based on structure and process dimensions placed a growing administrative burden on programs and reduced the time for resident teaching, mentoring and assessment.

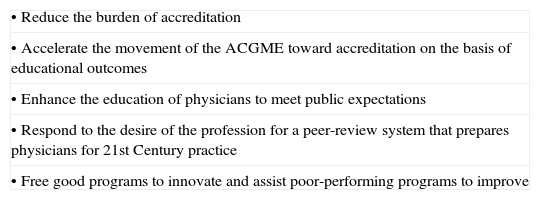

To address the lack of progress in the movement toward competency-based education the ACGME board of directors emphasized four priorities in its 2005 strategic plan, with the intent of facilitating the emergence of a new, outcomes-based model of accreditation: 1) fostering innovation and improvement in the learning environment; 2) increasing the accreditation emphasis on educational outcomes; 3) increasing efficiency and reducing burden in accreditation; and 4) improving communication and collaboration with key internal and external stakeholders.8 Key attributes of the new model would be a more robust and meaningful use of data and educational outcomes, and a reduction in the burden of accreditation. The Next Accreditation System (NAS) was the new approach to outcomes-based accreditation that emerged from these strategic priorities.9 The NAS was designed to redirect the focus of the educational enterprise on learning processes and their outcomes, and to reduce the multitude of structure and process requirements.7 The aims of the NAS are shown in table 1. Besides basing accreditation on educational outcomes, key dimensions of the new accreditation model include continuous oversight of key parameters through annual data collection, and fostering innovation by allowing some deviation from detailed process standards for accredited programs with beneficial outcomes. A key element in this effort is accreditation based on educational outcomes using milestones based on the six competencies. The milestones reflect the trajectory of growth in a clinical specialty, and offer clear developmental steps along the process of competency acquisition.

Aims of the Next Accreditation System.

| • Reduce the burden of accreditation |

| • Accelerate the movement of the ACGME toward accreditation on the basis of educational outcomes |

| • Enhance the education of physicians to meet public expectations |

| • Respond to the desire of the profession for a peer-review system that prepares physicians for 21st Century practice |

| • Free good programs to innovate and assist poor-performing programs to improve |

ACGME: The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

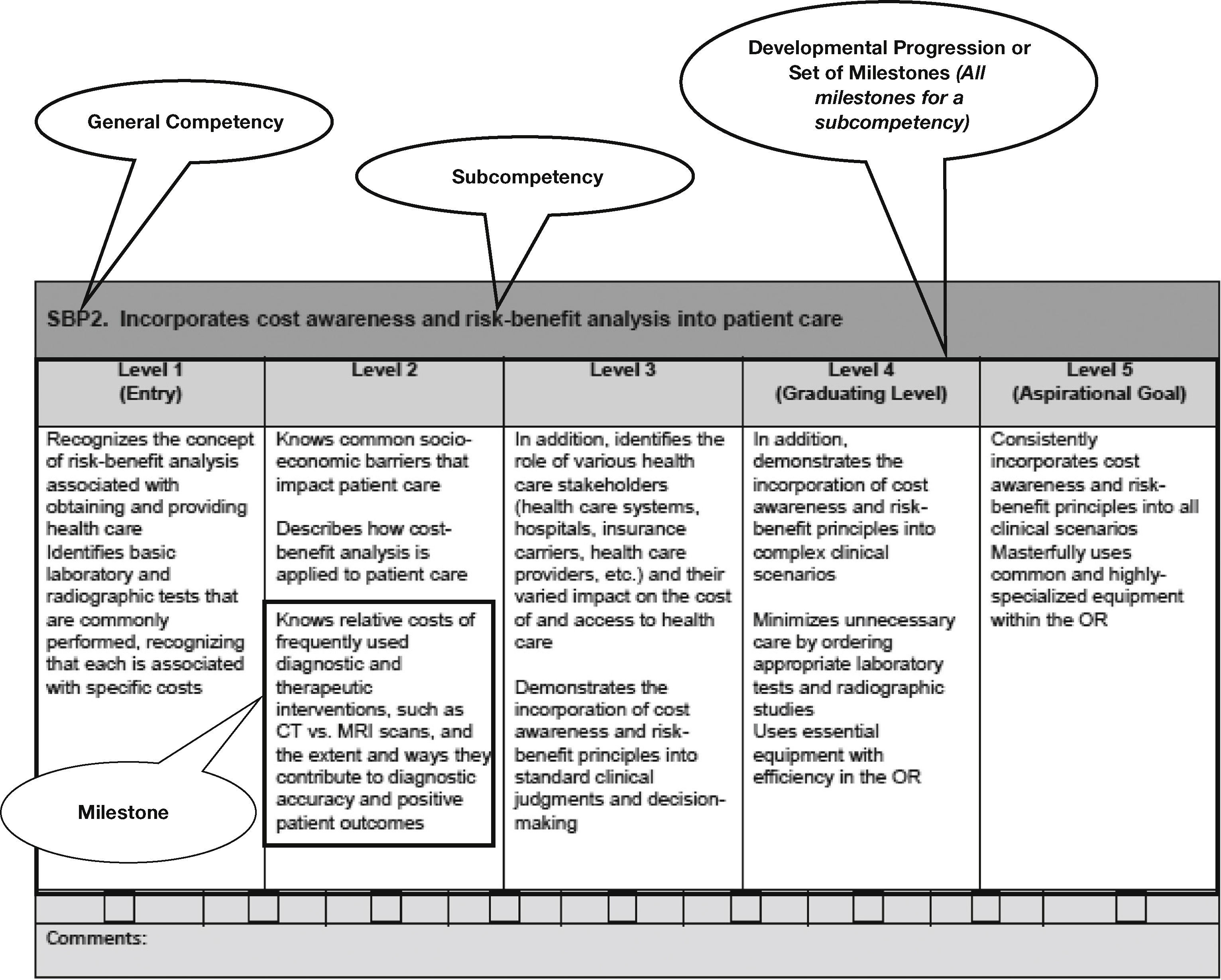

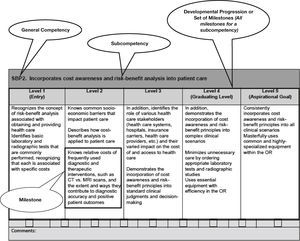

The development of the educational milestones development began in 2009 as a collaborative effort that involved the ACGME, the ABMS member boards, and other stakeholders. The milestones were conceived as a set of observable steps in residents’ professional development that describe progress from entry to graduation and beyond. The milestones’ 5-level developmental framework describes the developmental steps in the acquisition of competence from novice to expert/master. An example for practice-based learning and improvement is shown as Figure 1. Milestone development was informed by the literature, specialty curricula, stakeholder review, and initial testing. Each specialty community developed a consensus set of milestones in the 6 competencies.10 The milestones offer two advantages over the competencies: 1) they expand the competencies into a set of observable behaviors at levels of progression toward mastery, making learners’ progress more explicit; and 2) the level a completion of the formal education program represent the specialty-specific set of attributes associated with high-quality medical practice. The milestone are critical to achieving aims the NAS, particularly accelerating the use of outcomes in accreditation, and ensuring that the education of physicians met public expectations.

Example milestone in the ACGME template and with milestone nomenclature. ACGME: The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Notes. SPB2 is the notation for the second Systems-Based Practice set of milestones. The table is in the format of the milestone semi-annual reporting worksheet. First published in Swing et al.10 Used with permission of the ACMGE and the Journal of Graduate Medical Education.

Competency-based models for learning and assessment have long been used in other domains of education, and were adapted to medical education in the late 1970s.11 The focus on the skills set of graduates allows for greater learner-centeredness, de-emphasizes time-based learning, and creates enhanced accountability for the product of education.12 A competency-based approach in medical education, by focusing on attributes important to the practice of medicine, was thought beneficial by placing greater emphasis on elements of the curriculum such as ethics and attitudes, which may otherwise be overlooked in teaching and assessment.11 There has been increasing interest in the defining the attributes associated with high-quality medical practice, and expectations for physicians at the end of their formal training based on these attributes. In addition to the competencies, approaches that have defined desirable attributes for physicians include the CanMEDS roles,13 used across a number of different nations, the United Kingdom's Good Medical Practice14 and Tomorrow's Doctor,15 the Scottish Doctor,16 and Good Medical Practice – USA.17 While there are differences among these approaches, all share a common intent – defining the attributes of the high-performing physician, and there is considerable conceptual overlap.

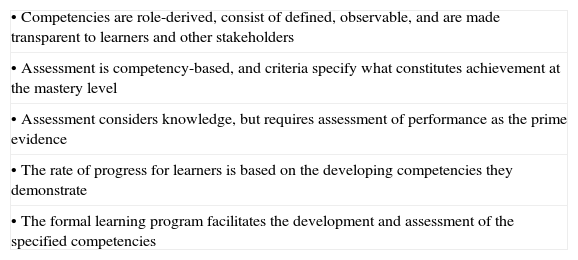

Characteristics of competency-based approaches to education include an individualized learning program, extensive formative feedback, and learner and educational program accountability. Completion of the learning program is not based on a set time frame, but on achievement of the specified competencies. Interest in competency-based education for teachers resulted in grants to universities, and a document from 1971 identified five essential elements for competency-based teacher education (table 2).18

Principles of competency-based education.

| • Competencies are role-derived, consist of defined, observable, and are made transparent to learners and other stakeholders |

| • Assessment is competency-based, and criteria specify what constitutes achievement at the mastery level |

| • Assessment considers knowledge, but requires assessment of performance as the prime evidence |

| • The rate of progress for learners is based on the developing competencies they demonstrate |

| • The formal learning program facilitates the development and assessment of the specified competencies |

Establishing the validity of the competencies and the educational milestones is important in ensuring the education community's confidence in the milestones and the success of a new outcomes-based approach for resident assessment and program accreditation.10 The development of the milestones by content experts, and the use of existing content blueprints, curricula and relevant studies, along with early testing by communities of practice establishes in internal medicine, pediatrics and surgery has produced an initial validity argument for the milestones.10 At the same time, the new approach to assessment that results requires making a judgment based on levels of educational attainment represents a significant departure from current assessment practice. A systematic review during the early development of the milestones, showed that progress and scoring rubrics across the range of educational settings showed some evidence for reliability and consequential validity but little other validity evidence.19 Early field work to test the milestones has produced data on the reliability and utility of the educational milestones in the assessment of physicians in training.20 Further validity evidence will require additional study of the utility of the milestones in assessment and accreditation, and linking the educational outcome data obtained through milestone-based assessments to the performance of physicians in practice. Proposed work has involved linking data from the formal graduate phase of physician education and information from the maintenance of certification process to generate data to be fed back to programs on the practice outcomes of their graduates.21

A barrier in the establishment of the validity and reliability of milestone-based assessments is the dearth of useful tools for competency-based assessment, with current research focusing on the merits of different assessment approaches and tools.22 Other challenges making validity inferences on the milestones result from a lack of meaningful outcomes on the performance of physicians in practice. An important article on validity in competency-based assessments presents four validity inferences using Kane's theoretic framework: 1) converting observations to scores; 2) going for from raw scores to universe scores; 3) assigning universe scores to target domain, and 4) making inferences from the target domain to the construct of interest.23 The use of Kane's framework highlights some of the challenges in making validity inferences about the assessment of learners in the context of real medical practice. For example, in converting observations to scores, a critical question is how scoring will address efficient collection and use of information vs. asking all possible questions, some of which may not be relevant to the give patient or case.21 The article concludes that standard psychometric methods and testing theory, such as item review, classic test theory, generalizability theory, information saturation, triangulation and member-checking procedures all are germane to enhancing validity in competency-based assessments.21 Also relevant to milestone validity is research has highlighted that the professional development of faculty providing the milestone-based assessments is critical to the quality of these assessments,24 with current efforts focused on enhancing faculty rater training.25

Establishing the validity of the milestones in the assessment of individual learners is an important precursor to establishing the validity of milestone assessments, aggregated to the program level, in outcomes-based accreditation of individual graduate medical education programs. The 1971 report on competency-based approaches for teacher training put forth 6 validity criteria for program evaluations using educational outcomes that are equally relevant to medical education: 1) improvement in individuals’ knowledge; 2) improvement in skills under laboratory conditions; and 3) improvement in skills under simplified training conditions; 4) the effect on behavior in a real practice context; 5) changes in outcomes (in the case of teacher training: student achievement) that can be seen in a short time frame; and 6) longer-range effects on outcomes (for teacher training, this encompasses student achievement in cognitive, affective and psychomotor dimensions).16 Evaluate a competency-based approach to teacher training using learner performance also requires measurement tools for the appropriate assessment of learners, and an approach to isolate and measure the portion of learner growth that can be attributes to the change in teacher training vs. learners’ given innate skills and individual ability.16 This is relevant to the accreditation of medical education programs using outcomes, and requires assessments of individuals’ capabilities at the entry into graduate medical education. Efforts are currently underway to expand the milestones into medical school education, 26 and to develop educational outcome expectations for the transition from medical school to graduate medical education.27

The application of the educational milestones in assessment and accreditationBy basing learner assessment on dimensions of performance relevant in the practice of medicine, the milestones produce feedback that is more meaningful to learners, and concurrently base the accreditation of programs on real educational outcomes, contrasted with other attributes that are less directly related to the performance capabilities of graduates. At the same time, a disadvantage of the competencies that is shared to some degree by the milestones is that the detailed language needed to describe the important qualities of physicians has produced descriptions of behaviors that are too long to be of practical for use in decisions about the need for supervision and in the provision of formative feedback to learners in clinical settings.28 Ten Cate and colleagues in the Netherlands developed the concept of entrustable professional activities (EPAs).29 EPAs are tasks or responsibilities that can be “entrusted” to a trainee once he or she has reached the competence needed to execute these tasks with minimal or no supervision.29 An EPA requires specific knowledge and skills for execution, and the entrustment process involves decreasing the level of supervision as trainees develop competence, with entrustment decision based on a specified level of competence that is attained by the given learner. An advantage of EPAs is that they represent what every-day clinical tasks; as a consequence the language for assignment, “entrustment,” and immediate feedback can be briefer and less complicated.29 EPAs also can be implemented in a curriculum as a “schedule” of activities.29

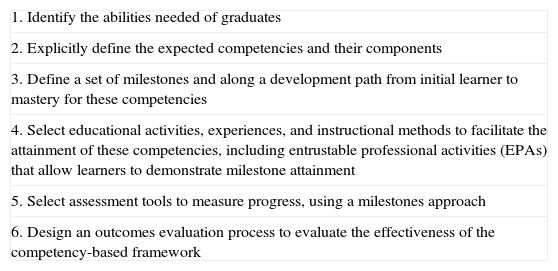

The general steps in the design and application of a competency-based education framework, using milestones and EPAs in a medical education context are shown in table 3. These steps can be followed in the narrow context of developing milestones and EPAs for a defined clinical task, such as a patient handover, or can be used in the development of a set of competencies and milestones for a given specialty. Current efforts to test the EPA concept has produced the finding that the development and use of milestones EPAS for clinical tasks such as patient handovers is feasible, and that it requires stakeholder engagement and a clear definition of the behavioral characteristics of each domain at each level of entrustment, along with assessment instruments that facilitate formative feedback and summative decisions.30

Steps in developing and applying a competency-based education framework.

| 1. Identify the abilities needed of graduates |

| 2. Explicitly define the expected competencies and their components |

| 3. Define a set of milestones and along a development path from initial learner to mastery for these competencies |

| 4. Select educational activities, experiences, and instructional methods to facilitate the attainment of these competencies, including entrustable professional activities (EPAs) that allow learners to demonstrate milestone attainment |

| 5. Select assessment tools to measure progress, using a milestones approach |

| 6. Design an outcomes evaluation process to evaluate the effectiveness of the competency-based framework |

The implementation of the milestones in the accreditation of physician training programs as part of the NAS entails twice yearly assessments of all residents in each accredited program. At the program level, the Milestone assignments are done in each by a clinical competency committee (CCC) comprised of faculty that aggregated the available assessments for a given resident, and using a consensus process, assigns the level that represent the resident's performance on each of the specialty milestones. This information is provided back as feedback to individual learners, and aggregate program level data from these assessments are submitted to the ACGME, where this information will be used in program accreditation. The consistent approach to assessing learner performance that is possible through the use of the milestones overcomes a disadvantage of the competencies, which produced idiosyncratic methods of assessment that were not consistent across programs. This will advance outcomes-based accreditation by collecting educational outcome data by using a standard approach to reporting.10 The standardized approach also will facilitate the collection of information on the validity of the milestones, which is critical to their use in learner assessment and program accreditation. The educational achievement of graduates also plays an important role in the required annual self-assessment for accredited programs, which includes an assessment of graduate performance. The expectation is that in the coming years the measures for this dimension will expand beyond the focus on performance on certification examinations. Approaches already used include surveys of the organizations hiring graduates, and of the graduates themselves. Discussions about the desired outcomes of clinical education, and the performance of educational programs in attaining these outcomes are beginning to engage the education, clinical practice and health care community.17 Relevant in this context is work by leaders of the organizations hiring physicians to define the skill set physicians needed to practice in a reformed health care environment, and to identify gaps in the six competencies and in the performance of graduates of physician education programs.31

The future of physician assessment and accreditation of physician training programsThe approach to the assessment of learners and training programs was evolving when the competencies were introduced, and it will continue to evolve. The growing focus on learning outcomes shifts evaluation of the educational program further along Kirkpatrick's classic framework for assessing the outcomes of learning that has been used for the past 50 years in evaluation training interventions across a range of domains.32 The use of the milestones has moved the assessment of physician trainees to Kirkpatrick level 3 – assessment of performance in a real-world context, including observational data on individuals’ performance.32 In 2015, there are developments in the assessment of medical education that will influence the assessment and accreditation for the future; these elements will form the basis of the assessment and accreditation system that will follow the NAS.33 Key attributes of this future system include an enhanced focus on the quality of clinical care in the settings that provide the context for resident education, and a focus on the clinical skills of faculty and their capacity to serve as clinical role models for residents. Evidence shows that the quality of care in settings in which physicians train has an effect on the quality of care they deliver for at least a decade and a half into the professional career,34 and research on individuals’ development of expertise that shows it is influenced by the expertise of their teachers and mentors.35 This will require enhanced focus on attributes of faculty, their clinical skills, and their capacity for serving as clinical role models. This will require linkages between educational and clinical attributes of teaching settings, essentially moving assessment to Kirkpatrick level 4 – the collection and analysis of data on the effects of the educational intervention on patient outcomes, and micro- or macro- health system performance,32 along with an enhanced focus on quality and safety parameters in the evaluation of sponsoring institutions.36

The clinical careers of the graduates produced by the current competency- and outcomes-based approach will span the next three to four decades. In 2001 the US Institute of Medicine of Medicine (IOM) declared health care in the 21st century is delivered by interprofessional teams, and highlighted problems with the traditional, single-profession models of education that do not prepare health professionals for the team-based approaches to care.37 The report puts forth six aims for the healthcare system: care should be effective, safe, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.37 The IOM competencies have been used to define goals and objectives for professional formation and development across a range of health professions. Dimensions of the competencies and milestones relevant to the IOM aims include physicians’ ability to apply quality improvement concepts in a clinical context, understanding health care as a system, communication and teamwork skills, and practice-based learning and improvement, including lifelong learning through self-directed studies, reflection and interaction with peers.37 In addition, as new physician competencies emerge that are relevant to patient care, population health, resource stewardship and other attributes of good medical practice, the use of a competency- and educational outcomes-focused approach through the milestones will enhance the ACGME's ability to ensure their successful incorporation into physicians’ skills sets. Likely new areas include understanding population health including improving the nation's health status,38 overcoming racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare,39 and attaining the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's “triple aim” of improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction); improving the health of populations; and reducing the per capita cost of health care.40

ConclusionThe focus on educational outcomes through the use of the milestones ensures that graduates of accredited training programs demonstrate the relevant skills and competencies for 21st century practice. Aggregated to the program level, the Milestones contribute to an accreditation approach that uses programs’ learning outcomes as a metric of their actual educational achievements vs. a measure of their potential to educate residents or fellows. Ongoing work to improve milestone assessments includes the development and validation of milestone-based assessment tools, and enhancing training and professional development for faculty making milestone assessments. Establishing the validity of the milestones will require longitudinal study of their use in assessment and accreditation, and linking educational outcomes to the performance and clinical outcomes of physicians in practice.