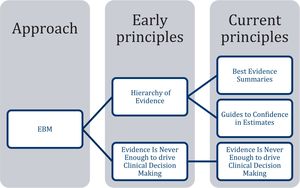

“Evidence-based medicine” (EBM) proposes methods, techniques, and instruments for verifying, incorporating, and applying scientific information in individual and public health. However, the principles and postulates of EBM have evolved over time. Our objective was to analyze the principles and postulates of EBM and compare them with current research, to identify possible myths. We conducted a review and analysis of the literature to identify the current principles of EBM and its most disseminated postulates. Subsequently, we compared these postulates with scientific evidence and EBM principles to identify potential myths. We identified 3 current principles of EBM: “EBM is a systematic summary of the best available evidence”, “EBM provides guidance to determine the level of confidence in estimates”, and “Evidence is never enough to drive clinical decision making.” Additionally, we identified 4 widely disseminated postulates: (1) Systematic reviews are at the top of the evidence pyramid, (2) randomized clinical trials are the best type of evidence, (3) expert opinion is a type of scientific evidence, and (4) to make health decisions, we should only use scientific publications. We critically assessed these postulates against scientific evidence and EBM principles, revealing them to be "myths." We identified f4 myths of EBM and proposed solutions to foster a more accurate interpretation and utilization of scientific evidence.

La «medicina basada en la evidencia» (MBE) propone métodos, técnicas e instrumentos para verificar, incorporar y utilizar información científica en la salud individual y pública. Sin embargo, sus principios y postulados han cambiado con el tiempo. El objetivo fue identificar y contrastar los principios de la MBE con los mitos de su aplicación usando la lógica dialéctica. Se realizó una revisión literaria para identificar los postulados actuales de la MBE. Confrontamos estos postulados con evidencia científica y principios Mbe para identificar posibles mitos. Identificamos 3 principios actuales de la MBE: 1) «Es un resumen sistemático de la mejor evidencia disponible», 2) «proporciona criterios para decidir el nivel de confianza de las estimaciones», y 3) «la evidencia nunca es suficiente para tomar decisiones clínicas"; además, identificamos 4 postulados ampliamente difundidos: 1) las revisiones sistemáticas están en la cúspide de la pirámide de evidencia, 2) los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados son la mejor evidencia, 3) la opinión de los expertos son un tipo de evidencia científica, y 4) para tomar decisiones en materia de salud solo debemos utilizar publicaciones científicas. Estos postulados no se condicen con la evidencia científica y resultaron en 4 «mitos» de la MBE, sobre los cuales proponemos soluciones para lograr una mejor interpretación y uso de la evidencia científica.

There is increasing demand that medical practices be based on reproducible and ethically obtained scientific evidence. The evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been a milestone in the systematization of medical knowledge and in seeking strategies to make better clinical and health decisions.1,2

Like any theoretical body, EBM presents principles from which we deduce postulates that must be contrasted with current scientific advances. However, the initial focus of these postulates is being questioned or misinterpreted when they are put into practice. Although some health professionals consider that these postulates are immovable (turning them into “myths”), they could and should be modified, as in any scientific program that aims to remain valid.2,3

The EBM principles proposed by Guyatt et al. are: (1) The “EBM is a systematic summary of the best available evidence”, (2) “EBM provides guidance to decide the level of confidence in estimates”, and (3) “Evidence is never enough to drive clinical gecision Making” (Fig. 1).4 Out of these principles, postulates have been derived that we consider being contradictory to the theory and practice that currently guides the MBE, which could turn them into myths. Therefore, our objective was to compare the principles and postulates of the EBM with the results of current research to identify any contradictions (myths), and to propose potential solutions.

EBM postulatesWe have identified 4 widely disseminated postulates that have now formed into myths. Applying dialectical logic, we contrast these myths with the principles of the MBE and current evidence, identifying their contradictions (Table 1).

Cases not compatible with the postulates.

| Myth | Cases | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| SR are at the top of the evidence pyramid. | Case 1: An SR that included 6 RCTs (521 participants), aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of abdominal drainage to prevent intraoperative abscesses after an appendectomy in patients with complicated appendicitis compared to not using abdominal drainage. No conclusive results were reported to reduce intraperitoneal abscess, operative site infection, morbidity, mortality, or hospital stay, the authors propose more and better studies to determine the effects of abdominal drainage in this population.1 | SRs are not always sufficient to achieve conclusive or reliable results. |

| RCTs are the best type of evidence. | Case 2: Using RCT, nivolumab was found to be safer and more effective when compared with dacarbazine as a treatment for previously untreated BRAF-free melanoma patients since it improved overall progression-free survival.2Case 3: A first observational study identified an association between smoking and lung cancer. Subsequent “in vitro” animal and observational studies corroborated this association.3,4Case 4: An SR evaluated the usefulness of the different diagnostic test studies to diagnose stroke, it confirmed the utility of CT which is currently widely recommended.5,6 | There are different useful designs for different types of research problems to solve. |

| EO is a type of scientific evidence located at the bottom of the evidence pyramid. | Case 5: During the COVID-19 virus pandemic, experts pointed out and recommended drugs such as chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, or ivermectin to be used as part of the therapeutics for this disease.27 These recommendations were not confirmed after multiple investigations and were no longer recommended.7,8Case 6: Mustafá’s study aimed to describe a method for formulating evidence-based recommendations when there is an absence of published scientific evidence. Through a survey, he collected information from a panel of experts on venous thromboembolism in pediatric patients. The strategy allowed for the formulation of 12 recommendations based on the “experience of experts”, using a systematic and transparent methodology.9 | EO is not a type of scientific evidence but expert evidence. |

| To make health decisions we should only use scientific publications | Case 6: During the process of formulating a recommendation to the PICO question: “In patients with large vessel ischemic stroke, what is the most effective and safe arterial reperfusion therapy?”, a systematic review concluded that mechanical thrombectomy was superior to intravenous thrombolysis, given the high certainty of this estimate, it would be usual to make a strong recommendation, however, the expert panel; including local information, such as limitations for its implementation and high costs, formulated a “conditional” recommendation for the use of thrombectomy.10 | Scientific evidence is not the sole resource to consider when making decisions. |

SR: systematic reviews. RCT: randomized clinical trials. EO: expert opinion.

1. Li Z, Li Z, Zhao L, Cheng Y, Cheng N, Deng Y. Abdominal drainage to prevent intra-peritoneal abscess after appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021(8).

2. Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(4):320-30.

3. O'Keeffe LM, Taylor G, Huxley RR, Mitchell P, Woodward M, Peters SAE. Smoking as a risk factor for lung cancer in women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e021611.

4. Wynder EL, Graham EA. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma: a study of six hundred and eighty-four proved cases. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1950;143(4):329-36.

5. Brazzelli M, Sandercock PA, Chappell FM, Celani MG, Righetti E, Arestis N, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus computed tomography for detection of acute vascular lesions in patients presenting with stroke symptoms. 2009(4).

6. Sequeiros-Chirinos JM, Alva-Díaz CA, Pacheco-Barrios K, Huaringa-Marcelo J, Huamaní C, Camarena-Flores CE, et al. Diagnóstico y tratamiento de la etapa aguda del accidente cerebrovascular isquémico: Guía de práctica clínica del Seguro Social del Perú (EsSalud). Acta Médica Peruana. 2020;37(1):54-73.

7. Maguiña Vargas C, Gastelo Acosta R, Tequen Bernilla A. El nuevo Coronavirus y la pandemia del Covid-19. Revista Médica Herediana. 2020;31(2):125-31.

8. Lamontagne F, Agoritsas T, Siemieniuk R, Rochwerg B, Bartoszko J, Askie L, et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs to prevent covid-19. bmj. 2021;372.

9. Organization WH. Living guidance for clinical management of COVID-19: Living guidance, 23 November 2021. World Health Organization; 2021.

10. Mustafa RA, Garcia CAC, Bhatt M, Riva JJ, Vesely S, Wiercioch W, et al. GRADE notes: How to use GRADE when there is “no” evidence? A case study of the expert evidence approach. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2021;137:231-5.

In the thesis (first stage), we present these 4 postulates derived from the principles of the MBE. These postulates are routinely applied in the clinical and/or sanitary field, and for many professionals are unquestionable, so we consider them “myths”.5,6 In the antithesis (second stage), updated evidence and cases that contrast the postulate were reviewed. Finally, in the synthesis (third stage) we resolve the thesis/antithesis contradiction and we propose an updated proposal of the initial postulate.

Myth 1: Systematic reviews (SR) are at the top of the evidence pyramid- •

Thesis: SR are at the top of the evidence pyramid because they represent the best scientific evidence to make decisions.7 They have been incorporated into different classification systems that are still used in the development of Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) such as AHA/ASA or UPDKS8,9 and consider them as type A, type I, or type 1 evidence. In addition; its conclusions are considered high quality only because they are located at the top of the evidence pyramid due to their greater methodological validity.

- •

Antithesis: SRs (with or without a meta-analysis) are a set of secondary research designs that synthesizes the results of primary studies, such as RCTs (randomized control trials) and diagnostic test studies.10,11 They allow drawing quantitative or qualitative conclusions from a set of primary studies. Confidence in their estimates and conclusions depends on the quality of the primary studies incorporated and the rigor with they are prepared.12 An SR on an intervention, although rigorously developed, whose estimates indicate more benefit than risk could yield low or very low quality conclusions, due to the low validity, reliability, directionality, and/or precision of the primary studies. The conclusions would not be sufficient to recommend such an intervention but to identify knowledge gaps where more and better research is needed.13

- •

Synthesis: Murad proposes that SRs synthesize the best scientific evidence available from the different types of studies. But they are not necessarily the best evidence to guide decisions. Moreover, they should not be part of the pyramid of evidence or considered the top, instead they should be understood as a magnifying glass that evaluate, through a systematic search, the quality of the studies found and synthesized (quantitative or qualitative) the evidence to issue conclusions that can then be used in making the best health decisions, as happens when making recommendations following GRADE’s “Evidence to Decision (EtD)”.14,15

- •

Thesis: Within this point, we identify 2 related postulates:

- -

It has been postulated that RCTs are the gold-standard of research designs in human studies. They have been considered the best available scientific evidence against which other study designs have been compared, sometimes to simulate them and other times to recognize their potential limitations.13,16

- -

Scientific evidence can be ranked based on research design. In this way, the expert opinion is at the base of the pyramid while the ECAs are usually at the top of the pyramid.4,7

- •

Antithesis: The second principle of the EBM: “EBM provides guidance to decide the level of confidence in estimates” indicates that the hierarchy of evidence is based on the evaluation of the biases that could contain. For a question about the therapeutic efficacy of an intervention, RCTs are better compared with observational studies.17 However, not all the questions that need to be answered are about therapeutic efficacy. There are questions about risk factors, screening, diagnosis, prognosis, burden of a disease, quality of services, and efficiency. These questions require different designs other than RCTs, such as observational studies for incidence or prevalence, risk factors or prognosis; diagnostic test studies to establish diagnostic accuracy or precision; qualitative studies for quality of services; and cost-effectiveness studies for the efficiency of an intervention (Table 2).18

Table 2.Types of clinical questions and the most appropriate design to produce answers.

Type of question Primary designs Secondary designs Treatment RCT For each of the types of questions and designs, an SR could be performed. Prevention RCT Frequency Cohort studyCross-sectional study Diagnosis Diagnostic test study (cross-sectional or prospective) Etiology Cohort studyCase–control study Prognosis Cohort–survival study SR: systematic review. RCT, randomized clinical trial. Modified from García CAC & Gaxiola GP.24

- •

Synthesis: Each study design has its own features and utility. Therefore, establishing a hierarchy based on design is not realistic or useful for decision-making if the different biases that could be contained in the research are not taken into account. When looking for evidence to solve a problem, the study design will be only one of several aspects to consider.9,19 When faced with a problem of efficacy, ECAs will be preferred to observational; and for a problem of frequency or impact of a disease, observational studies will be most appropriate.20,21 The confidence of their estimates will depend on the evaluation of their biases.

- •

Thesis: OE is still considered as a type of evidence located at the base of the pyramid of evidence, and in the absence of higher evidence this can and should be used.22

- •

Antithesis: EO should not be considered a type of scientific evidence if it is not part of a validated process. Therapeutic decisions not based on scientific evidence, present a greater risk of error and bias.14,23

- •

Synthesis: EO is not a type of scientific evidence. However, the experience of a health professional can be transferred to scientific evidence through validated techniques such as consensus, surveys, or interviews. In addition, it can serve as an input to generate recommendations or make decisions in scenarios where there is no scientific evidence or evidence is limited.24

- •

Thesis: Scientific evidence makes rigorous use of the scientific method whose process culminates in a scientific publication. Therefore, since its origins EBM have proposed using the best available evidence, that is scientific publications.25

- •

Antithesis: Sacket postulated that the “MBE means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best external clinical evidence”.2,4 Currently, the third principle of the MBE proposes that “evidence is never enough to drive clinical decision-making”. This postulate mentions that it is necessary to incorporate multiple criteria that complement the scientific evidence and that they must be considered when making a health decision.22

- •

Synthesis: The EBM consists of the integration of the best-available scientific evidence with the clinical experience and values/preferences of the patients in whom the intervention will be applied.2,26 Therefore, applying an MBE approach does not mean using only and directly the results of scientific publications but that decisions should be developed in 2 moments: (1) the first, where the best-available scientific evidence is systematized and (2) the second, where multiple criteria, such as local information on the feasibility, efficiency, and equity of interventions, are integrated to formulate a decision contextualized to the scenario where such decisions will be applied.22

We propose 4 new postulates for better use of scientific evidence in medical decision-making: (1) RS synthesizes available scientific evidence methodologically but is no better than primary studies. (2) Each problem in the field of health care corresponds to a suitable type of research to generate a solution. (3) EO is not a type of scientific evidence, but could be transferred to the scientific evidence through its methodological systematization. (4) The decision-making proposed by the MBE follows 2 moments: first, the synthesis of the best-available scientific evidence and, second, the formulation of decisions through the consideration of multiple criteria.

Ethical approvalEthical approval was not required for this review.

Statement of informed consentThere are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

FundingThe university of the Lord of Sipán provided support for the publication of this article.