Social enterprise (SE) studies are gaining ground as an emerging research domain owing to the duality characterizing their business models for tapping the triple bottom line (TBL) principle, which is a framework measuring the three pillars of sustainability: people, planet, and profit. This rising attention to SE has led to scattering in the research structure and knowledge spillover. Although publications have attempted to regroup this domain, extant analyses lack scientific coverage. By reforming previously adopted research approaches and redesigning metadata retrieval constraints, this study revisits, dissects, and synthesizes relevant SE-related studies to identify the current dominance, recent developments, and future directions of SE studies. Through a bibliometric review that combines descriptive, network, and content analyses, our findings reveal ten avenues worth pursuing, categorized under the research scope, research trajectory, and analytical dimensions. Finally, this study presents practical implications that support the institutionalization of SEs that holistically meet the TBL principle.

Social enterprises (SEs) are for-purpose organizations established by their founders, also known as sociopreneurs, based on a combination of personal interests in addressing social issues and entrepreneurial skills. SEs embrace paradoxical agendas that have proven to be favorable for easing societal and environmental issues while being rational regarding the economic variables that finance their operations. The principle of SEs, which taps the triple bottom line (TBL) elements coined by Elkington (1994), is suitable for advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) initiative (Littlewood & Holt, 2018).

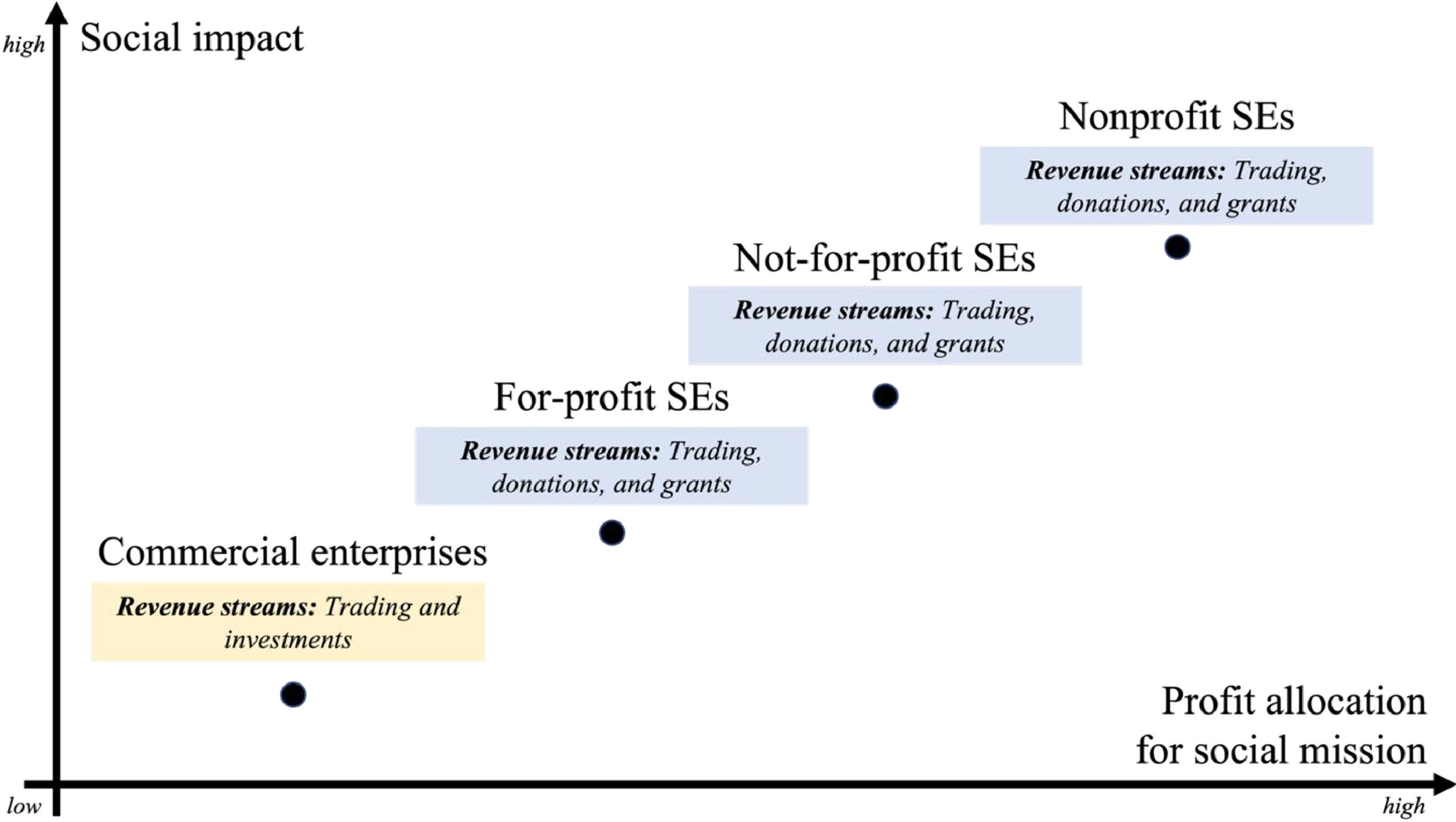

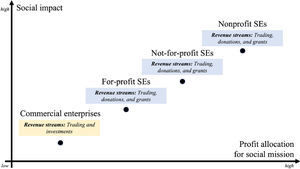

The institutionalization of SEs has evolved worldwide and has been examined extensively. Business lines developed under such third-sector organizations flourish in terms of breadth and depth (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010; Hazenberg et al., 2016). By streamlining the nature of for-profit and nonprofit organizations (NPOs) through market-driven approaches, SEs establish a not-for-profit business model to thrive and become financially stable, while meeting their non-economic objectives (Barraket et al., 2017; Chandra, 2016; Romani-Dias et al., 2018). Although legal structures vary across countries, SEs commonly pursue their financial bottom line by selling products or services with the intent of allocating a large sum of their profits to strengthen communities and the environment. To this end, social missions, revenue streams, and profit distributions are the three key elements that consistently structure and distinguish SEs from commercial enterprises (Fig. 1).

Following the proliferation at the practical end, scholars’ interest in examining SEs as research domains has increased. Although the domain is approached mainly through theoretical and conceptual research, recent studies have gradually progressed to fill this gap by empirically investigating the conceptualization and operationalization of the SE research domain Erpf et al. (2019); Rawhouser et al. (2019). Considering the increasing attention to the SE research domain by practitioners and scholars, overwhelming knowledge spillover in this field has led to the dissemination of scattered research structures.

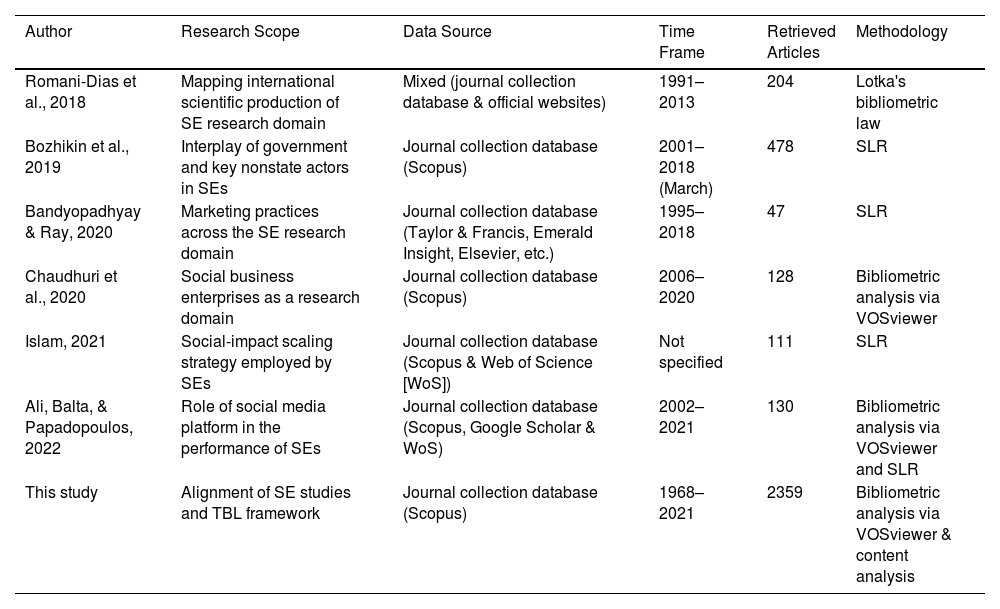

Research investigating the chronicle of the SE research domain is currently required to manage and collate a dispersed body of knowledge. Table 1 lists existing systematic literature reviews (SLRs) that attempt to understand the avenues of scientific literature on SEs. In addition to sharing similar objectives, most existing studies agree that bibliometric analysis is an eminent SLR approach for deconstructing complex knowledge structures. In contrast, existing studies have demonstrated flexibility in leveraging data sources. Scholars examining the SE research domain have framed SLR studies by generating metadata either from journal collection databases or directly from the websites of specific SE-related journals. Nevertheless, SLR publications found that the domain has consistently demonstrated remarkable annual research growth over the past five years.

Prior SLR studies in SE research domain.

| Author | Research Scope | Data Source | Time Frame | Retrieved Articles | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romani-Dias et al., 2018 | Mapping international scientific production of SE research domain | Mixed (journal collection database & official websites) | 1991–2013 | 204 | Lotka's bibliometric law |

| Bozhikin et al., 2019 | Interplay of government and key nonstate actors in SEs | Journal collection database (Scopus) | 2001–2018 (March) | 478 | SLR |

| Bandyopadhyay & Ray, 2020 | Marketing practices across the SE research domain | Journal collection database (Taylor & Francis, Emerald Insight, Elsevier, etc.) | 1995–2018 | 47 | SLR |

| Chaudhuri et al., 2020 | Social business enterprises as a research domain | Journal collection database (Scopus) | 2006–2020 | 128 | Bibliometric analysis via VOSviewer |

| Islam, 2021 | Social-impact scaling strategy employed by SEs | Journal collection database (Scopus & Web of Science [WoS]) | Not specified | 111 | SLR |

| Ali, Balta, & Papadopoulos, 2022 | Role of social media platform in the performance of SEs | Journal collection database (Scopus, Google Scholar & WoS) | 2002–2021 | 130 | Bibliometric analysis via VOSviewer and SLR |

| This study | Alignment of SE studies and TBL framework | Journal collection database (Scopus) | 1968–2021 | 2359 | Bibliometric analysis via VOSviewer & content analysis |

Previous SLR studies presented in Table 1 reveal that the extant research structure lacks scientific coverage. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, while numerous theoretical frameworks have been used to investigate the contributions of SEs to sustainable development, the TBL framework has not been applied in previous studies. As the TBL principle is the main pillar of sustainability, the aforementioned gap raises important questions about the extent to which existing SE-related studies address sustainable development of the community, environment, and economy at large. In this regard, our domain-based SLR study seeks to improve the findings of existing SLR studies by reforming previously adopted research approaches and redesigning metadata retrieval constraints. As a stand-alone study, this SLR aims to advance the SE research domain by presenting improved insights into its current dominance, recent developments, and future research directions. Following Kraus et al. (2022), by revisiting, dissecting, and synthesizing relevant studies, this investigation contributes to illuminating scholars with research gaps and worth-pursuing research avenues in the field of SEs that holistically meet the TBL framework.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 explains the methods used for metadata retrieval and analysis. Section 3 delineates the results of the descriptive and network analyses incorporated into the content analysis. Section 4 extends the discussion of the overall bibliometric analysis with worthwhile research directions and practical implications. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper with the findings according to the research objectives and highlights the limitations of our study.

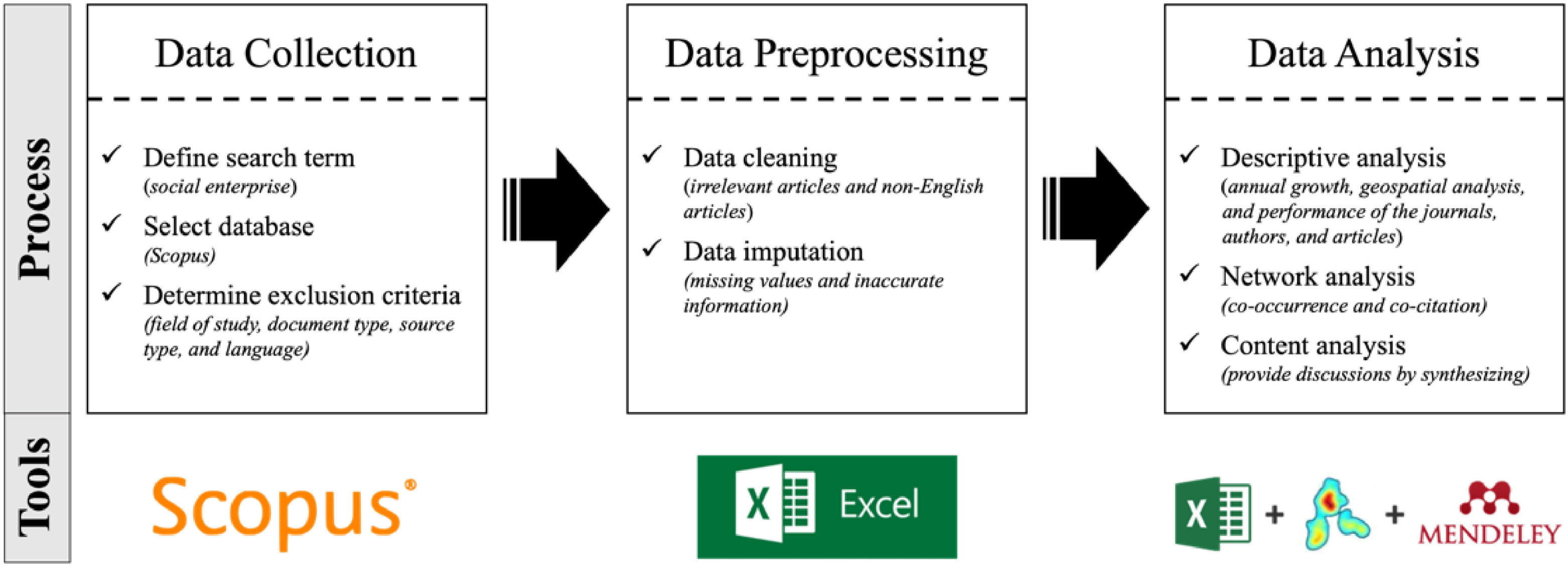

Research designMethodsThis study combined quantitative and qualitative methods. The former involved a bibliometric analysis, whereas the latter involved a content analysis. Bibliometric analysis, which encapsulates descriptive and network analyses, is a renowned statistical approach for extracting a list of relevant scientific articles compiled in the retrieved metadata (Gallego-Valero, Moral-Parajes, & Román-Sánchez, 2021; Kraus et al., 2022; Romani-Dias et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2020). As a stand-alone approach, bibliometric analysis is prone to unreliability, as the results may be biased by siloed insights (Gao et al., 2020; Koseoglu, 2016). Therefore, this study employed content analysis to further analyze the insights and maintain their reliability (Kraus et al., 2022). Fig. 2 shows the three building blocks that constitute the research design. The first two stages, data collection and data preprocessing, are presented in the following subsections. The data analysis stage is explained in Section 3.

Data collection and preparationSimilar to the guidelines for conducting SLR studies presented by Kraus et al. (2022, pp. 2584–2586), the data collection process was initiated by defining the search term, followed by selecting the journal database. According to Chadegani et al. (2013), eminent journal databases are characterized by their capacity to cover multidisciplinary research fields and provide transparency regarding publication details. Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) are qualified and the most extensively used databases in bibliometric studies (Firmansyah & Faisal, 2020). Scopus is generally considered to have a more comprehensive collection of scientific articles than other databases (Falagas et al., 2008; Mishra et al., 2017). Compared to WoS, Scopus is estimated to cover 70% more sources (Brzezinski, 2015). Considering the aim of this study, data were collected from Scopus.

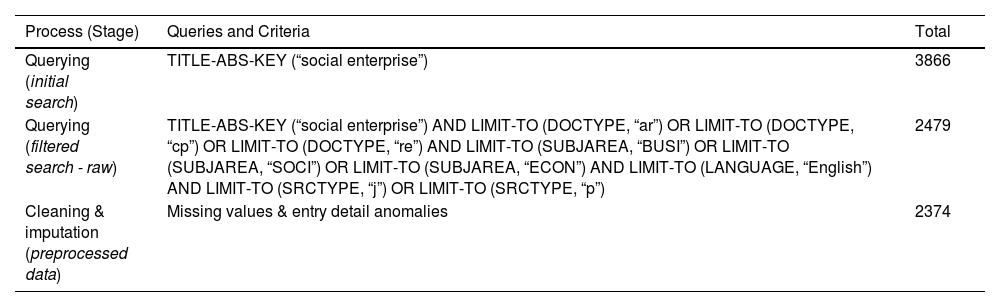

Correspondingly, “social enterprise” was defined as the search term, and 2021 was set as the end year of the publications to be retrieved. The initial search returned 3866 scientific articles. Following Garousi (2015), the relevance of the search results was increased using the filters available on the Scopus website. Thus, the SE-related articles compiled in our metadata were characterized as English manuscripts (articles, reviews, and conference papers) published in scientific journals or conference proceedings in the fields of social sciences, business, management, accounting, economics, econometrics, and finance. This setup trimmed the initial search results to 2479 articles. For further preprocessing and analysis, the CSV and RIS files of the filtered search results were directly imported from the Scopus database.

As bibliometric analysis is sensitive to variables and keywords in the sampling pool, data cleaning is required to avoid misinformation that potentially shifts the analysis results (Rossa-Roccor et al., 2020). Using Microsoft Excel, the metadata were preprocessed to omit and impute entries with missing values, irrespective of the field of study and inaccurate details. This step was performed meticulously in iteration to ensure that the articles compiled in the metadata were aligned with the focus of this study (Saunders et al., 2019). Finally, 2374 articles that matched the scope of this study were obtained. Table 2 summarizes the data collection process, queries, criteria, and total articles compiled through the process.

Data collection and preprocessing.

To evaluate the quality of existing scientific articles and uncover emerging themes across the SE research domain, raw and preprocessed CSV metadata were utilized.

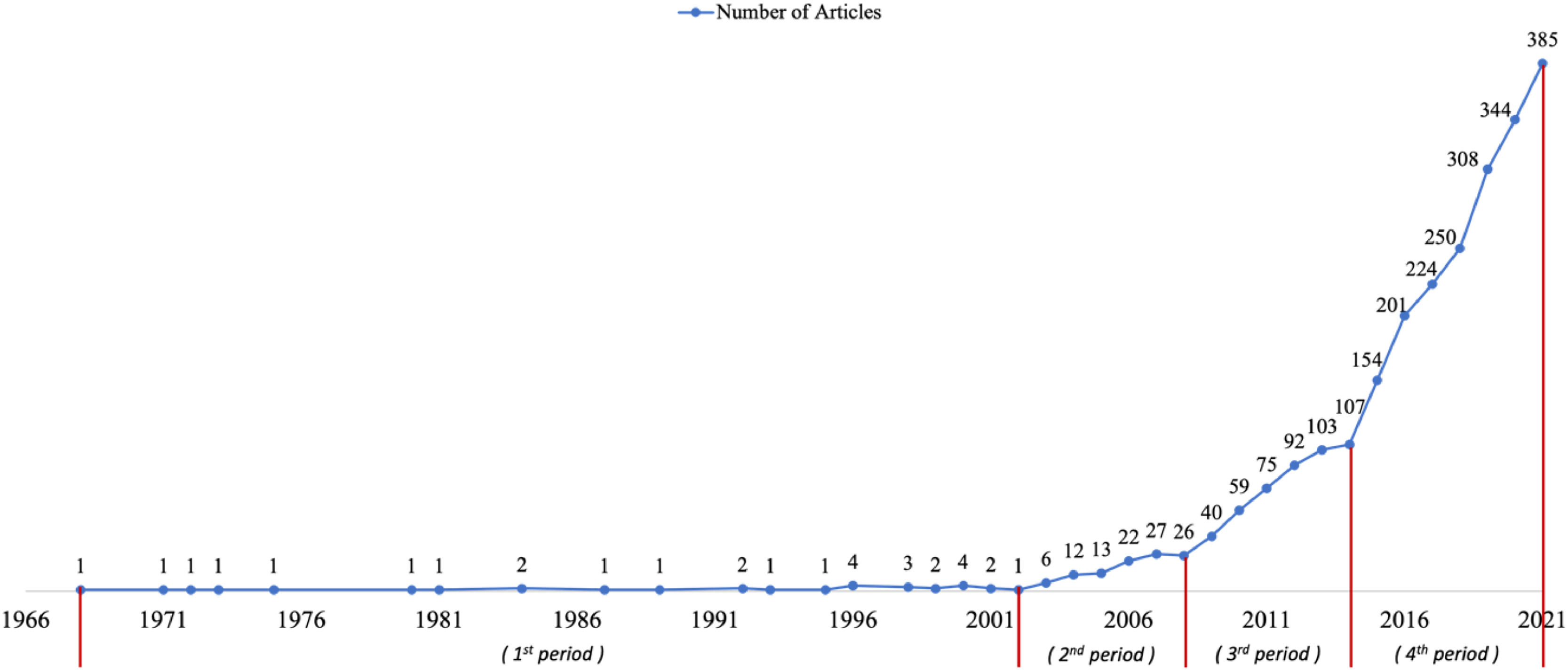

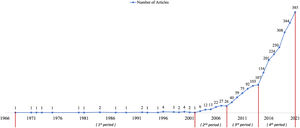

Descriptive analysisAnnual growthAccording to the raw metadata, in the sample pool of 2479 SE-related articles, 89.39% were journal articles, 5.37% were conference proceedings, and 5.24% were reviews. Encompassing the years between 1968 and 2021, Fig. 3 shows an exponential trend with an average periodic growth rate of 46.74%. This significant increase confirms the growing interest of scholars in SEs as a research topic.

Following Mostafa (2020), this study further categorizes the rising annual growth of SE studies into four periods according to the trends. By extending this periodic characterization to the keyword classification of studies in each period, this study revealed the evolutionary trajectory of SE studies in meeting the TBL framework.

In the first period (1968–2002), which was marked as the initial stage, SE studies were scarce, and the annual publication rate fluctuated, with only one or two articles published per year. Rather than aligning social business with sustainability elements, scholars initially explored the research domain by establishing theories through exploratory studies that investigated the institutionalization of SEs (Blau, 1972; Dees, 1998; Prabhu, 1999; Young, 2001; Zietlow, 2001).

During the second period (2003–2008), an initial growth stage emerged, with moderate proliferation accompanied by constant annual growth. Having become familiar with the concept of SEs as businesses with social objectives, scholars began to justify ways to improve community livelihoods through comparative and case studies (Haugh, 2007; Nwankwo et al., 2007; Peredo & Chrisman, 2006; Tracey et al., 2005; Young, 2006).

The third period (2009–2014) was the expansion stage owing to a subtle increase in SEs publications, with a growth rate of 58.2% compared with the previous period. At this stage, scholars attempted to expand the research focus toward environmental development; however, proliferation was generally marginal (Davies & Mullin, 2011; Mysen, 2012; Osti, 2012; Parris & McInnis-Bowers, 2014; Tremblay et al., 2010; Vickers & Lyon, 2014).

Finally, the fourth period (2015–2021) delineated the rapid growth stage owing to steep surges in the annual publication rate throughout this period. Scholars captured the urge to evaluate the social value-creation performance of SEs in supporting economic development (Azmat et al., 2015; Bhatt & Ahmad, 2017; Bilan et al., 2017; Desa & Koch, 2015).

Based on this evidence, it was determined that the SE research domain has yet to reach either the consolidation or stabilization stage, which are commonly characterized by slow annual growth. This finding corroborates the status of SEs as an emerging research domain.

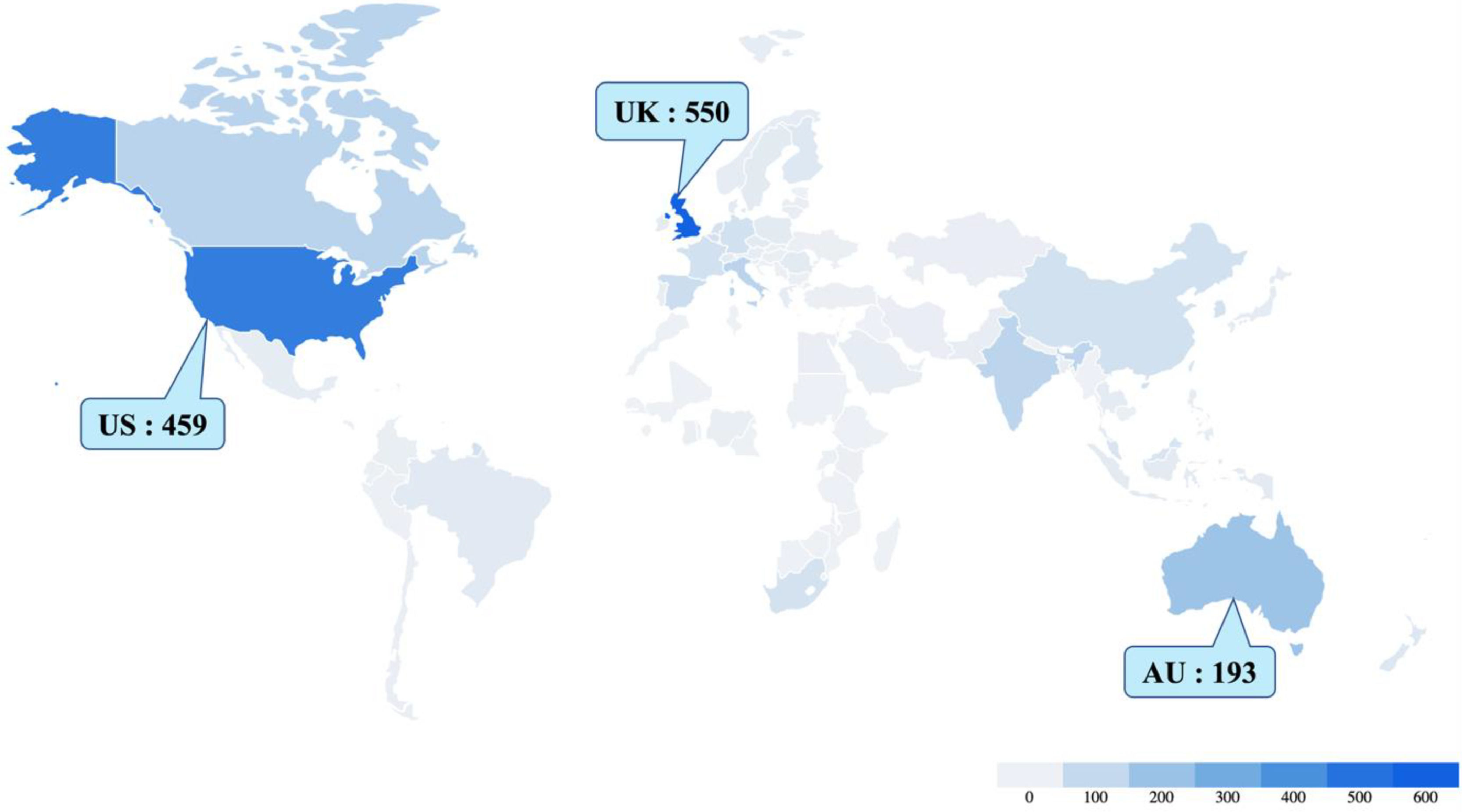

Geospatial distributionGrounded in geospatial data, our metadata comprised SE-related articles written by scholars affiliated with institutions in 100 countries. Despite the worldwide presence of SEs, Fig. 4 shows uneven contributions, with 62% of the total number of publications dominated by institutions in the United Kingdom (550), United States (459), Australia (193), Canada (125), Italy (120), India (116), Spain (80), Belgium (69), Germany (66), and France (66).

As the first SE-related article in our metadata used England as a case study (Morley, 1968), early recognition in the United Kingdom was regarded as the pragmatic reason for the prevalence of SE studies in the country. One study determined that the history of SEs can be traced back to the Victorian era (Dart, 2004). During the early stages of economic difficulties, SEs, which were generally considered unprofitable for commercial businesses across the European Union (EU), were acknowledged for their innovative solutions that successfully addressed social issues (Defourny & Nyssens, 2008; Santos, 2012).

Meanwhile, in the United States, the development of SEs began between the 1980s and the 1990s through commercialization, with the help of private organizations (Kerlin, 2006). Before this period, NPOs were known as the forerunners of SEs, until funding for their charitable activities was reduced during the retrenchment period. Considering these conditions, major differences between SEs in EU countries and the United States lie in their organizational governance, in which the latter leans toward individual approaches, whereas the former embraces participatory approaches (Huybrechts & Defourny, 2008). The presence of SEs in the United Kingdom and the United States was anticipated due to the large gap in social and welfare issues following the crisis in both countries, which encouraged scholars to use them as case studies (OECD, 2021a) and influenced the maturity of the social policies implemented in both countries (OECD, 2021b).

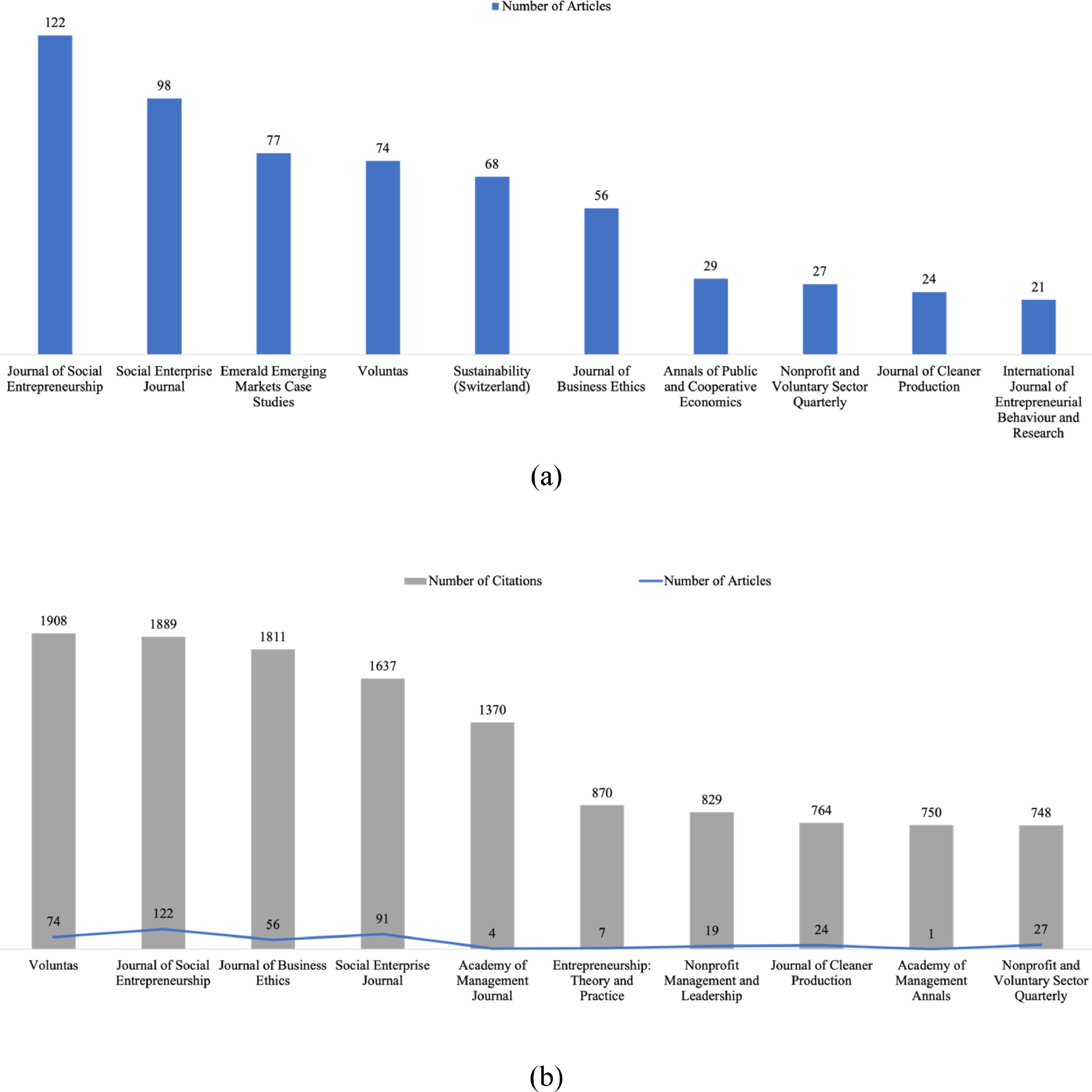

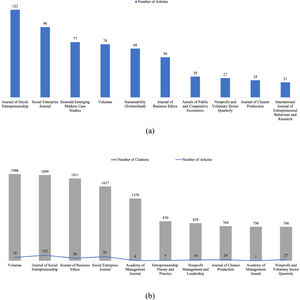

Journal performanceBy dissecting publication sources, our metadata listed more than 850 scientific outlets indexed by Scopus. In terms of population distribution, 25% of the retrieved SE-related articles were featured in the top ten most populated journals (Fig. 5a). Approximately 13% of the metadata were from the three most prolific journals. Nonetheless, only one of the three most prolific journals accumulated a high citation count and occupied one of the three most influential positions (Fig. 5b). Six of the ten most prolific journals were also influential.

As shown in Fig. 5b, this trend suggests that journal performance was not consistently driven by the number of publications. Although quantity may be one of the factors supporting the influence of scientific outlets, the data showing that more than half of the journals with lower total publications placed at higher positions in Fig. 5b contradict this assumption. Accordingly, this finding suggests that the quality of journals and the number of published articles were not positively correlated. Thus, this study agrees with Mishra et al. (2017) that the number of citations is an appropriate parameter for measuring the performance of scientific articles.

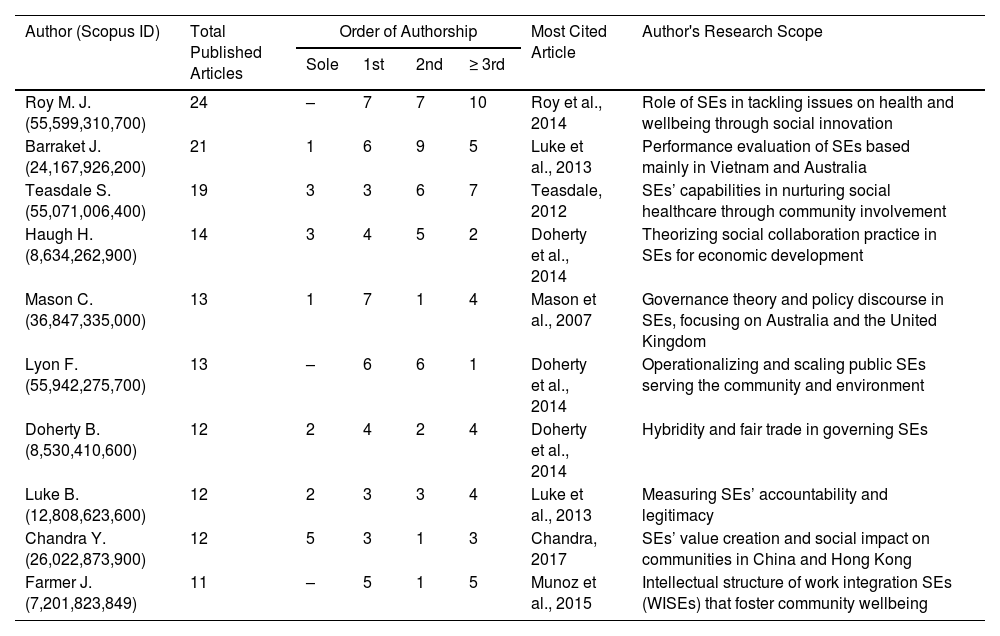

Author performanceBy examining the authors’ ID, we identified 4316 authors listed in the metadata. Some scholars have published their manuscripts as sole authors; however, many scholars have chosen a co-author track. The nature of co-authorship in boosting authors’ productivity was analyzed through the distribution of authorship. Table 3 presents the top ten most productive authors, along with details related to the number of articles produced by the end of 2021. On average, the top ten most prolific scholars contributed to the development of the SE research domain for approximately 11 years by publishing at most two articles annually. Assessing their state of authorship, this study determined that collaboration with other prolific authors boosted authors’ productivity by 13% compared to being the sole author.

Top ten most productive authors in SE research.

| Author (Scopus ID) | Total Published Articles | Order of Authorship | Most Cited Article | Author's Research Scope | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sole | 1st | 2nd | ≥ 3rd | ||||

| Roy M. J. (55,599,310,700) | 24 | – | 7 | 7 | 10 | Roy et al., 2014 | Role of SEs in tackling issues on health and wellbeing through social innovation |

| Barraket J. (24,167,926,200) | 21 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 5 | Luke et al., 2013 | Performance evaluation of SEs based mainly in Vietnam and Australia |

| Teasdale S. (55,071,006,400) | 19 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 7 | Teasdale, 2012 | SEs’ capabilities in nurturing social healthcare through community involvement |

| Haugh H. (8,634,262,900) | 14 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | Doherty et al., 2014 | Theorizing social collaboration practice in SEs for economic development |

| Mason C. (36,847,335,000) | 13 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 4 | Mason et al., 2007 | Governance theory and policy discourse in SEs, focusing on Australia and the United Kingdom |

| Lyon F. (55,942,275,700) | 13 | – | 6 | 6 | 1 | Doherty et al., 2014 | Operationalizing and scaling public SEs serving the community and environment |

| Doherty B. (8,530,410,600) | 12 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | Doherty et al., 2014 | Hybridity and fair trade in governing SEs |

| Luke B. (12,808,623,600) | 12 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | Luke et al., 2013 | Measuring SEs’ accountability and legitimacy |

| Chandra Y. (26,022,873,900) | 12 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Chandra, 2017 | SEs’ value creation and social impact on communities in China and Hong Kong |

| Farmer J. (7,201,823,849) | 11 | – | 5 | 1 | 5 | Munoz et al., 2015 | Intellectual structure of work integration SEs (WISEs) that foster community wellbeing |

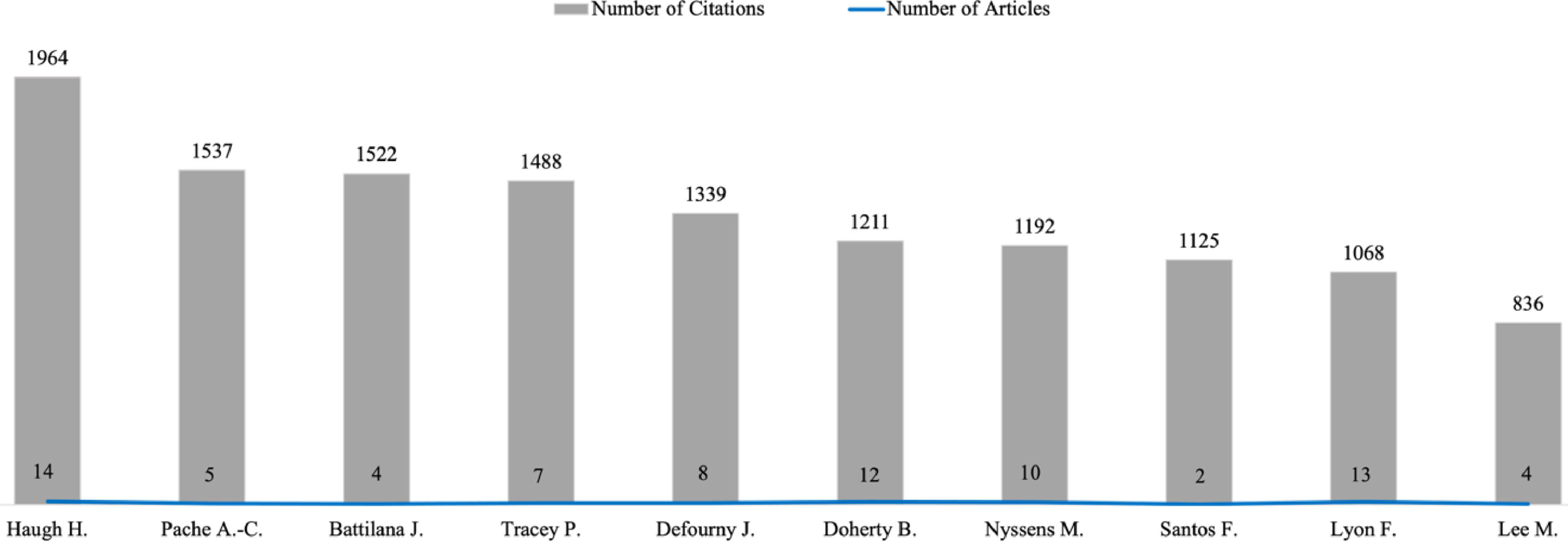

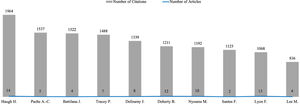

The top ten most influential authors (Fig. 6) were evaluated based on the basis of their number of citations, and only three of the top ten most productive authors were found to produce influential articles. Aligning the results in Fig. 6 with the pattern of co-authorship in Table 3, this study determined that an article titled “Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda,” co-authored by Haugh, Doherty, and Lyon, made the authors stand out among the top ten most influential authors in the SE research domain. Cited by 572 scholars, this article accounted for 29%, 47%, and 54% of citations received by Haugh, Doherty, and Lyon, respectively. In this regard, the results implied that collaboration increased not only scholars’ productivity but also their influential status across a research domain.

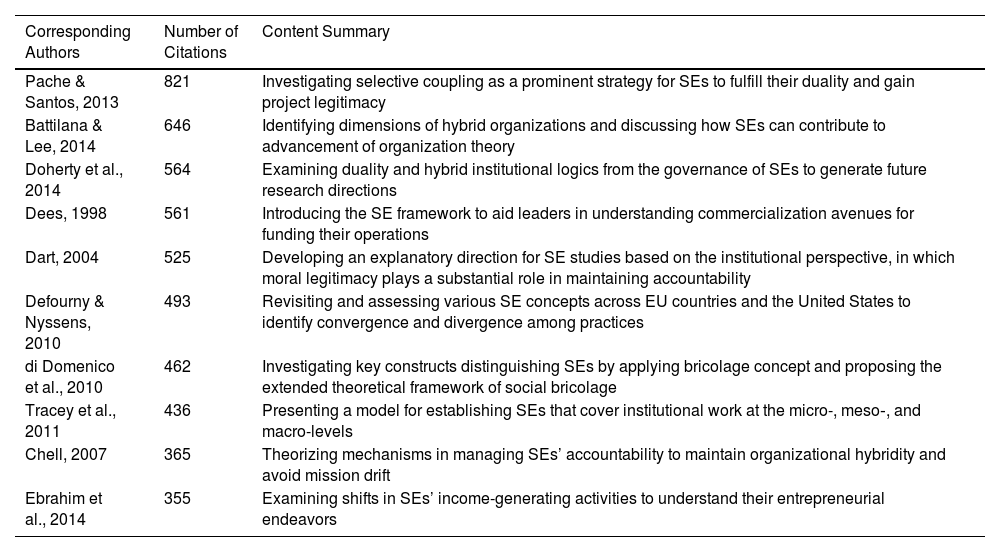

Article performanceBy sorting the number of citations, we identified the top ten most-cited SE articles (Table 4). On average, the majority of the most-cited articles were published between 2010 and 2014. Theoretically, the older the article, the higher is the number of citations. Therefore, the fact that the article by Pache and Santos (2013) dominated the list with 821 citations was unusual. After comparing the research scope of the most-cited articles, this study concluded that studies discussing strategies for handling the challenges of paradoxical objectives (e.g., managing duality, maintaining accountability, gaining legitimacy, and avoiding mission drift) were the most engaging in the SE research domain. Scholars were also likely to cite articles covering the conceptualization and operationalization of SEs. This was revealed by considering the close range of research focus between landmark articles in the metadata written by Dees (1998), which was similar to the work of Battilana and Lee (2014) and Doherty et al. (2014). This finding confirmed that the SE research domain remained in its infancy but was evolving.

Top ten most cited SE articles.

| Corresponding Authors | Number of Citations | Content Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Pache & Santos, 2013 | 821 | Investigating selective coupling as a prominent strategy for SEs to fulfill their duality and gain project legitimacy |

| Battilana & Lee, 2014 | 646 | Identifying dimensions of hybrid organizations and discussing how SEs can contribute to advancement of organization theory |

| Doherty et al., 2014 | 564 | Examining duality and hybrid institutional logics from the governance of SEs to generate future research directions |

| Dees, 1998 | 561 | Introducing the SE framework to aid leaders in understanding commercialization avenues for funding their operations |

| Dart, 2004 | 525 | Developing an explanatory direction for SE studies based on the institutional perspective, in which moral legitimacy plays a substantial role in maintaining accountability |

| Defourny & Nyssens, 2010 | 493 | Revisiting and assessing various SE concepts across EU countries and the United States to identify convergence and divergence among practices |

| di Domenico et al., 2010 | 462 | Investigating key constructs distinguishing SEs by applying bricolage concept and proposing the extended theoretical framework of social bricolage |

| Tracey et al., 2011 | 436 | Presenting a model for establishing SEs that cover institutional work at the micro-, meso‑, and macro-levels |

| Chell, 2007 | 365 | Theorizing mechanisms in managing SEs’ accountability to maintain organizational hybridity and avoid mission drift |

| Ebrahim et al., 2014 | 355 | Examining shifts in SEs’ income-generating activities to understand their entrepreneurial endeavors |

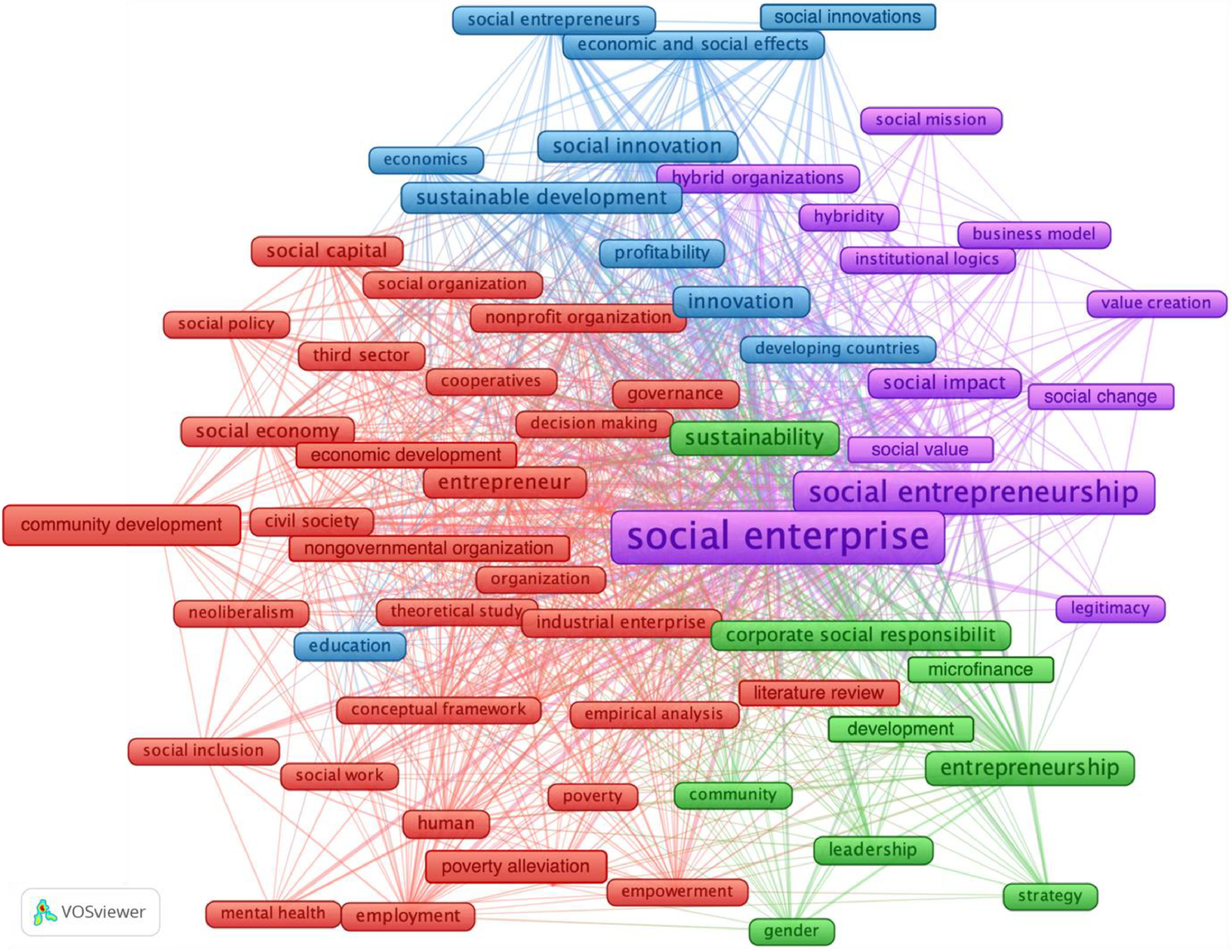

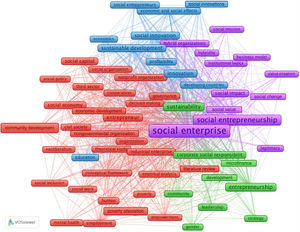

Co-occurrence analysis is a bibliometric approach that considers keywords as the basic unit of analysis. VOSviewer was used to build a co-occurrence network comprising the frequency and interconnections of keywords examined in the same article. Co-occurrence analysis is ideal for guiding scholars in identifying the topical themes comprising a research domain. The threshold of occurrence was set to 20, and redundant keywords were excluded. Fig. 7 comprises 66 qualified keywords from the 6405 clustered into four topics: core studies, economic development, institutionalization of SEs, and community development.

The first cluster, core studies, included 33 keywords that focused on the methodologies and areas of discussion examined by the scholars. Scholars have approached the SE domain through conceptual frameworks, theoretical studies, organizational frameworks, literature reviews, and empirical analyses. For the area of discussion, scholars investigated the institutionalization of SEs in terms of their nature as NPOs and as part of industrial enterprises. This study identified keywords such as “social capital,” “decision making,” “stakeholder,” “neoliberalism,” “social inclusion,” “cooperatives,” “poverty alleviation,” and “empowerment” as the topics that raised the most concern. These keywords implied the pivotal role of SEs in advancing the United Nations’ SDGs.

The second cluster, economic development, was composed of ten keywords indicating the significant contributions of SEs to the economic improvement of people in developing countries through social innovation initiatives. Drawing on these inferences, scholars have highlighted the knowledge and importance of incorporating social entrepreneurship into formal and informal educational systems to strengthen economic development (Kirby & Ibrahim, 2011; Lee, 2021; Zhu et al., 2016). According to Hockerts (2018), students enrolled in social entrepreneurship courses demonstrate improved self-efficacy, high perceived social support, and social entrepreneurial intent.

The third cluster, institutionalization of SEs, pooled a group of 14 keywords linking scholars’ interests in the hybridity concept embraced by SEs. Due to SEs’ novel business model, keywords such as “institutional logics,” “social value,” “social mission,” and “social change” signified the unsettling comprehension of SEs’ building blocks for value creation, along with the organizations’ legitimacy in fulfilling their role as a social business. Some keywords were also found in the most-cited articles. Examining the legitimacy of SEs, Dart (2004) found that their evolution is perceived to be and practiced toward commercial and revenue-generating directions. As a shift in SEs may lead to mission drift, scholars designed frameworks to assess and propose approaches for gaining external legitimacy (Hynes, 2009; Molecke & Pinkse, 2020; Ruebottom, 2013; Weidner et al., 2019; Yang & Wu, 2016; Yasmin & Ghafran, 2021).

The last cluster, community development, comprised nine keywords reflecting SEs’ capacity to provide communities of interest with access to opportunities and resources traditionally limited to them through entrepreneurship. Gender gap issues, specifically women's empowerment, emerged as the most-examined field across SE publications. Stemming from the notion of underrepresentation, the social values ingrained in the core existence of SEs matching the nature of women's behavior of attending to societal issues had the potential to increase their employability and leadership (Lyon & Humbert, 2012). As the pursuit of SEs was manifested extensively, cultural and social norms tied to the development level of a country should be considered in increasing women's employability (Nicolás & Rubio, 2016). Furthermore, the co-occurrence network identified corporate social responsibility (CSR) and microfinance as reliable strategies for SEs’ community development (Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Cornelius et al., 2008; Dunford, 2000; Lawania & Kapoor, 2018).

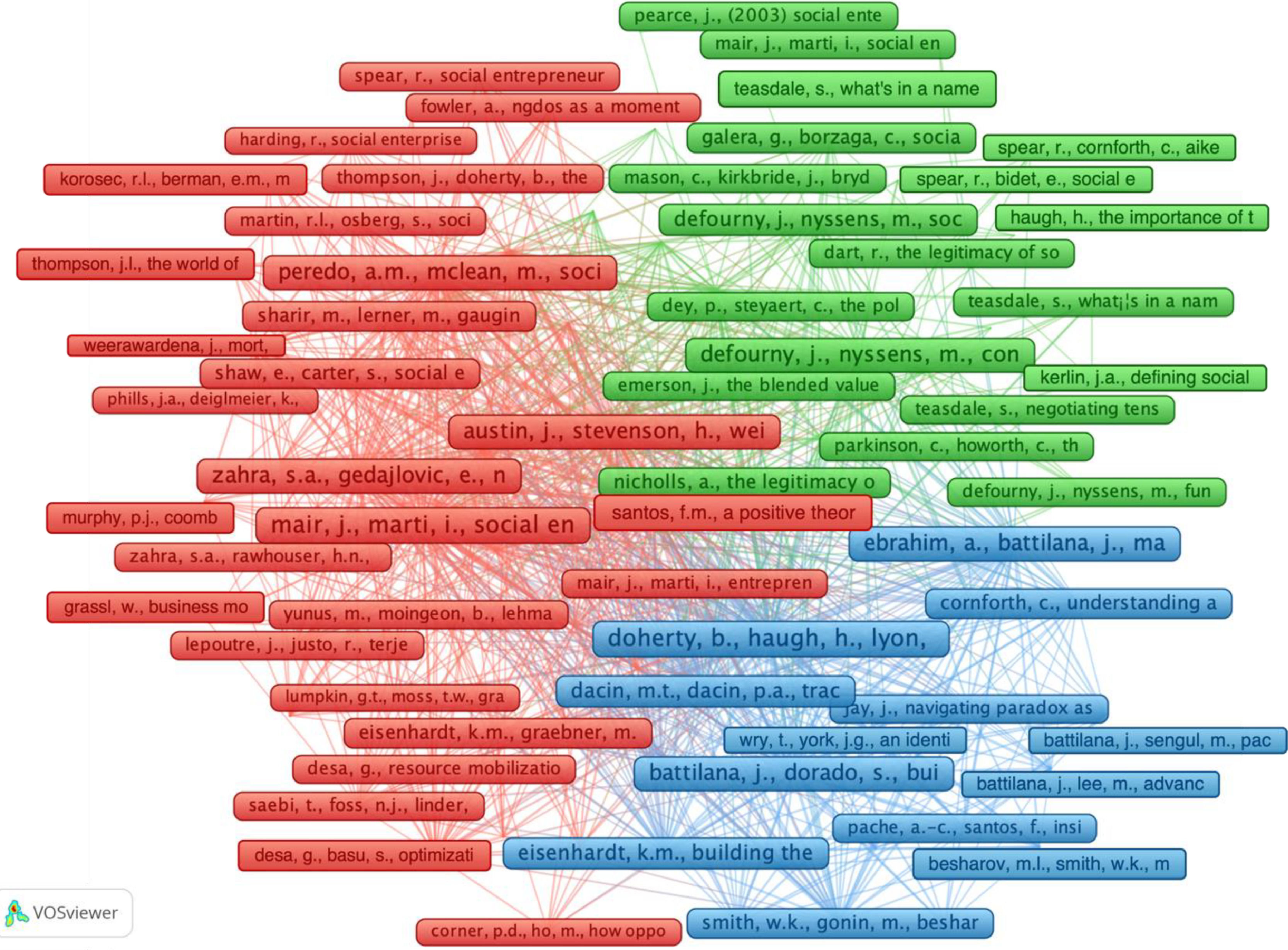

Co-citation analysisSupporting the co-occurrence analysis, the co-citation analysis was employed to validate the underpinning emerging topics according to the degree of correlation among the scientific publications cited together (Fu et al., 2018). Unlike the co-occurrence analysis, the co-citation network was generated by clustering all the highly correlated articles (Fig. 8). Therefore, the thematic grouping process under this approach may enrich insights with potential theoretical orientations, while making the identification of the major themes highly robust.

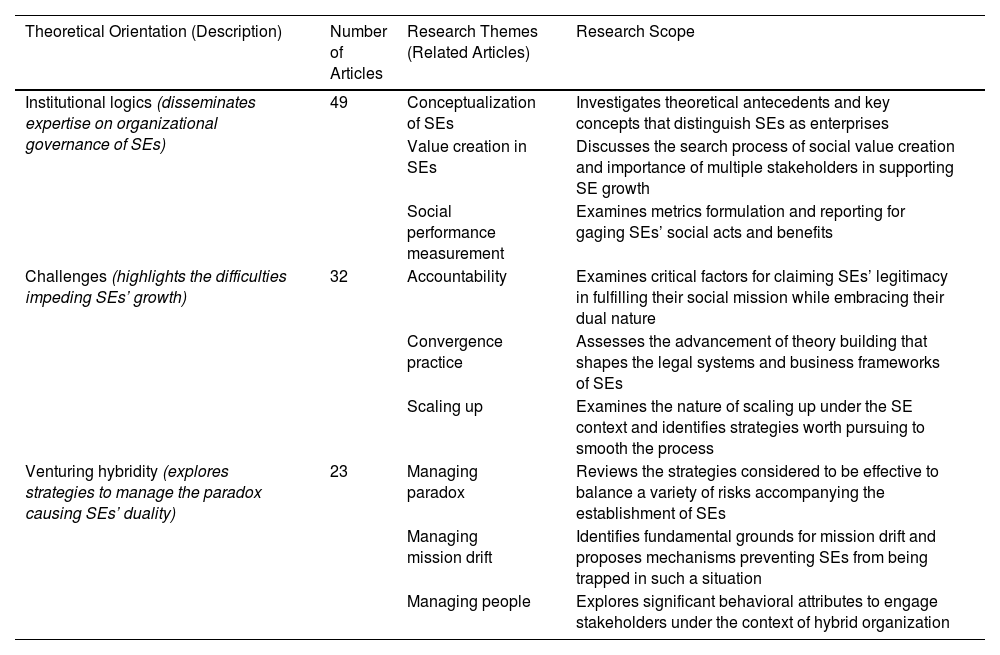

Co-citation analysis was conducted using VOSviewer, with 22 cited references as the minimum threshold. This procedure returned 103 interconnected articles from three clusters: institutional logics, challenges, and venturing hybridity. Following Du et al. (2021), this study carefully reviewed highly correlated articles to unearth concealed knowledge spillovers within clusters. Table 5 summarizes the three theoretical orientations that advanced the themes of recent SE research.

SE research clusters based on co-citation analysis.

The synthesis of our results highlights ten future research directions, categorized into three major areas: research scope (diversification of discipline, scope, and methods), research trajectory (institutionalization of SE and TBL elements, particularly the environmental dimension), and analytical dimensions (paradox management, social value creation, and social impact measurement).

Augmenting cross-disciplinary researchThe co-occurrence network analysis showed that the trajectory evolution of SE studies was aligned with the TBL framework. Although the disciplines associated with sustainable development studies varied, the analysis of journal performance revealed that the majority of existing studies in the SE research domain focused heavily on social sciences and business management. As the alignment of theory and social relevance is essential (Haugh, 2012), this study encourages scholars to improve the breadth of the SE research domain. More cross-disciplinary studies are suggested to ground future analyses in the fields of econometrics, environmental science, and decision science for policymaking.

Broadening the research contextAlthough SEs are emerging across Asian countries (Defourny & Kim, 2011), the geospatial analysis determined that SE studies are currently dominated by scholars affiliated with institutions in the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, India, Australia, and several EU countries. The dominance of developed countries is also reflected in the case studies presented in most SE studies. As the advanced practices shared by developed countries typically present beneficial insights for reverse engineering purposes, enriching the SE research domain with studies canvassing the institutionalization of SEs in big emerging market (BEM) economies and BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) is imperative. As the analysis of the authors’ performance demonstrates positive outcomes for collaborative research, our study extended the call by Haugh (2005) for scholars residing in developed countries to initiate collaborative research with those in BEM economies and BRICS countries, focusing on SE convergence practices and governance in such regions.

Diversifying research methodsThe evaluation of articles’ performance highlighted scholars’ tendencies to investigate the conceptualization, operationalization, and appropriate strategy to handle challenges in governing SEs through qualitative approaches, such as interviews, case studies, and literature reviews (Burga & Rezania, 2015). Moreover, an extended analysis of the authors’ performance revealed the same trend in theory and framework construction. Future research should focus on the application of quantitative approaches to advance this domain. Scholars could conduct future empirical studies by employing questionnaire surveys as research instruments. Alternatively, future studies focusing on regulating institutionalization or balancing the dual objectives of SEs through agent-based modeling, game theory, system dynamics, or other simulation methods would have significant novelty.

Institutionalization of SEsThe lack of consensus on the concept of SEs in some countries limits the theoretical background and policies governing them (Bull & Crompton, 2006; Galera & Borzaga, 2009; C. Mason & Barraket, 2015; Young & Lecy, 2014). An unclear understanding of scale-up strategies also indicates that the building blocks of SEs are not fully understood (Corner & Kearins, 2021; Dahles et al., 2020). To advance this research direction, future studies evaluating SE business models are expected to extend their scale and scope. Enrichment of the domain with discussions on how the regional socioeconomic context may affect the institutionalization of SEs across different regions is imperative, not only for improved institutionalization of SEs but also for theory convergence and refinement (di Domenico et al., 2010; Kerlin, 2010). For better dissemination, such research must be complemented by the investigation of organizational motives, social impacts, and innovation across diverse industries. Extending Austin et al. (2006), scholars may conduct comparative studies that distinguish the unique value propositions of SEs between industries. Furthermore, this review calls for future research to scrutinize the study by Winkler and Portocarrero (2018), who investigated people management in the SE context. As this direction has rarely been discussed, scholars can follow the studies by Bhati and Manimala (2011) and Sotirova (2019), who examined the challenges and strategies related to talent acquisition and retention across SEs.

Social developmentDespite the inclusion of diverse communities across SE operations, the existing literature shows a significant disparity in community development, leaning toward women's communities. While women's empowerment has been exhaustively covered, investigations on the involvement of other communities at the base of the pyramid (BoP) remain limited. Moreover, although studies that discuss the inclusion of disabled communities through the WISE business model can be traced in our metadata, the proportion of such studies remains low. Thus, future SE studies focusing on evaluating critical dexterity, challenges, and opportunities crucial to the success of WISEs in working with underserved communities may provide noteworthy insights. This direction can also be expanded to promote productive and equal opportunities for all by investigating the inclusion of wider communities, such as the younger generation, refugees, and other minority groups.

Economic developmentThe trajectory of SE studies positively contributes to economic development. Through the mobilization of resources and provision of job opportunities to wide communities, the evolution of SEs can aid underserved communities in generating wealth (Nicolás & Rubio, 2016). Studies on business model innovation in the SE research domain have praised the advent of the WISE framework, which positions BoP communities as partners rather than beneficiaries. Through these mechanisms, the framework is considered a sustainable wealth-generating business model that can effectively alter the mindsets of different communities (Farmer et al., 2016). To support the scarce research in this direction, future studies are recommended to extend the implications of SE practice for economic development by examining strategies for growing collaborative networks (Lyon & Ramsden, 2006; Lyon & Sepulveda, 2009; Montgomery et al., 2012), division of responsibility mechanisms in collaborative projects (Mitzinneck & Besharov, 2019), and incentive policies under the WISE business model (Faulk et al., 2020; Gianfaldoni & Morand, 2015).

Environmental developmentThe results of the keyword co-occurrence analysis revealed imbalanced discussions of the TBL elements. Although SEs studies emphasizing the suitability of this business model for supporting social and economic development have proliferated, investigations on the role of this third-sector organization in addressing environmental issues are scant. Moreover, studies on environmental development have focused mostly on finding ways to increase energy efficiency and maximize profits through green production, while rarely considering social factors. As such, existing SE studies mostly addressed the double-bottom lines of the TBL framework. Therefore, this study calls for scholars to direct future SE studies toward the role of SEs in promoting environmental development. Specifically, the investigation of schemes for integrating all TBL elements in the operationalization of SEs could be an avenue worth pursuing.

Paradox managementSynthesizing the results of the co-citation network analysis, this study determined that paradox management is an imperative analytical dimension requiring further investigation. Paradoxical objectives commonly multiply the tension that can drag SEs toward mission drift (Cornforth, 2014; Smith et al., 2013). When SEs diverge from their core values, accountability issues follow, jeopardizing their organizational legitimacy. Therefore, minimizing the likelihood of SEs being trapped in mission drift is a groundbreaking initiative (Park, 2020). Considering the difference between SEs that operate under purely charity-based approaches and those that adopt mixed market-based approaches, future research should investigate the probable factors that may lead to mission drift in relation to the organizational form. Scholars can present hypothetical reasoning for settling or avoiding mission drift (Jones et al., 2020; Ramus & Vaccaro, 2017). However, groundbreaking studies similar to that of Bloodgood & Chae, 2010, who presented strategies for aiding SEs in gaining advantages from the paradox, would bring considerable novelty to this analytical dimension.

Social value creationAs founders’ values are deeply ingrained in the social values that SEs aim to tackle, acquiring the resources needed to meet social goals may lead sociopreneurs to become unethical (Kwong et al., 2017; Muldoon et al., 2022; Zahra et al., 2009). Under this research avenue, future research is expected to investigate the contextual variables driving sociopreneurs in selecting social values to pursue (Corner & Ho, 2010). As the dynamics of social value fulfillment are fluid, the process typically requires adjustments to maximize social impact. Therefore, future studies should explore mechanisms that can minimize the need to compromise predefined social values when necessary (Nicholls, 2010). In conjunction with this concept, studies on early intervention mechanisms to prevent sociopreneurs from adopting unethical practices are equally important.

Social impact measurementThe final analytical dimension was the measurement of social impact. Drawing on the myriad objectives of stakeholders across SEs, Costa and Pesci (2022) delineated the use of a multi-stakeholder approach to curate multidirectional social impact measurement metrics that align with the core values of SEs and the key roles of various stakeholders. Thus, the SE can secure funding from potential patrons (Steiner & Teasdale, 2016). To enlighten practitioners about useful approaches and metrics for formulating social impact measurements, investigations into approaches for building appropriate metrics for social impact measurement should be conducted (Ali et al., 2019; Maas & Liket, 2011). Scholars could address this research gap by conducting exploratory studies to analyze unique social and economic measures suitable for evaluating the overall performance of SEs (Cordes, 2017; Maier et al., 2015). Contextual aspects, such as industrial and organizational forms, can be added as limitations or constraints to studies in this direction (Kim & Ji, 2020; Millar & Hall, 2013). Similarly, future studies should examine the extent to which the adopted social impact measurements can influence the decision-making processes of different SEs.

Practical implicationsGrounded in the presented analyses and discussions, venturing beyond paradoxical objectives while advancing the achievement of the SDGs presents sociopreneurs with taxing challenges. Combining these insights, this study provides practical implications for each SDG element: economic development, social development, and environmental development.

To improve the economy of underserved communities while supporting enterprises’ financial needs, SEs should extend their social innovation initiatives by assimilating the WISE business model. Partnerships with communities at the BoP under this strategic thinking would enable SEs to not only succeed in the implementation of sustainable solutions for equal opportunities but also promote social capital that can alleviate more diverse social issues than poverty in the long run (Zainol et al., 2019). As this scouting process may be costly for small SEs operating in developing countries, SEs in such contexts should be encouraged to focus on improving the local community's economy by acting as agents to offset institutional voids (Goduscheit et al., 2021). Alternatively, SEs should continue supporting small local businesses with access to funding through microfinancing or the CSR programs in which they are involved.

To advance social development, SEs should actively search for opportunities to work with diverse communities, as this transparent measure may be reported as proof of their continuing growth and accountability (Bradford et al., 2020; McConville, 2017). Social initiatives are necessary for improving community inclusion in SE practices through collaborative projects or funding mechanisms. From honing entrepreneurial skills to scaling the native capabilities of targeted communities, sociopreneurs should evaluate the examined mechanisms that encourage SEs to engage disadvantaged groups, such as people with physical disabilities, neurodivergence, low qualifications, and social problems. In guiding an attempt to advance community inclusion to fruition, SEs should foresee the potential of the social networks they build to extend their social mission and develop the concept of social procurement.

To address the lack of discussion on environmental development, sociopreneurs must shift to the double-bottom-line measures generally embraced by their social businesses (Lyon & Fernandez, 2012). Regardless of the industry to which SEs belong, embedding environmental aspects as part of their social impact mission and business model is essential to fully embody the concept of social business, particularly to support the achievement of the SDGs. Accordingly, the incorporation of versatile green strategies such as green production, upcycling, and circular economy into existing SE operations is worth pursuing. A progressive approach to stimulating environmental development is well portrayed by the Flame Tree Initiative, which is an SE focused on fighting energy poverty in Malawi by collaborating with organizations that supply clean renewable energy. As illustrated in Subramanian (2015) and Sengupta et al. (2020), such enterprises can fully tap the TBL elements simultaneously, as their projects promote the improvement of quality of life (social development) and advancement of local entrepreneurial activities (economic development).

ConclusionsThe proposed research design could contribute to the improvement of the scientific coverage of existing SLR studies and illuminates the current dominance of the SE research domain, scientifically supporting the status of SEs as an emerging research field. Unfortunately, the influence of SE studies is dominated by scholars and cases from developed countries, such as the United Kingdom, United States, and most EU countries. In terms of methodology, the descriptive analysis shows that most existing SE studies are qualitative in nature, with highly cited topics revolving around conceptualization, competition, and strategies for addressing the challenges in SE governance.

By revisiting and dissecting the literature on SEs through network analysis, co-occurrence, and co-citation analyses, we demonstrated that the recent development of SE studies has covered all TBL elements: economic, social, and environmental development. Nonetheless, the number of keywords and cited topics across the SE studies representing each element indicates that environmental development is the only area that has rarely been discussed. Therefore, we call for future research to address other SEs in the energy sector and investigate novel environmental protection measures that can be embedded into SE operations.

Finally, this study concludes with an analysis of ten future research directions covering the research scope, research trajectory, and analytical dimensions to advance the SE research domain. This study presents practical managerial implications for sociopreneurs based on the TBL elements.

The decision to use a single search term during metadata retrieval may have led to missed details of SE concepts and practices. Thus, future SLR studies should establish a systematic search term formulation to improve metadata curation. Furthermore, this study does not discuss the weak legal bases of SE practices in several countries. With these limitations, future SLR research discussing government involvement and policy interventions in SE practices would fill the gaps in the present study. Regardless, this study contributes to the field by advancing ongoing scholarly investigations and the holistic sustainable development of SEs, while fostering an improved understanding of the SE research domain.

This work was partially supported by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan under grant numbers MOST 110-2621-M-011-001 and MOST 111-2410-H-011-019-MY3.