Critical Incident Reporting System (CIRS) have become most common patient safety tools in healthcare. The purpose of this study was to determine how effectively CIRS is used and how well healthcare professionals recognize it as a risk management tool. A quantitative approach using a cross sectional survey was adopted. The most common critical incidents were due to lack of personal attention and related to individual errors. The most of the critical incidents arise from non-adherence to guidelines and standards. CIRS can be seen as an effective clinical risk management tool that can be used to identify potential sources of critical incidents and help ensure patient safety at a healthcare organization.

El sistema de informes de incidentes críticos (CIRS) se ha convertido en la herramienta más común para la seguridad del paciente en la atención sanitaria. El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar cuán efectivamente se utiliza el CIRS y el modo en que los profesionales sanitarios lo reconocen como herramienta de gestión del riesgo. Se adoptó un enfoque cuantitativo, utilizando una encuesta transversal. Los incidentes críticos más comunes se debieron a la falta de atención personal y guardaron relación con los errores individuales. La mayoría de los incidentes críticos se derivan de la no adherencia a las directrices y estándares. El CIRS puede contemplarse como una herramienta efectiva de la gestión del riesgo clínico, utilizarse para identificar las fuentes potenciales de incidentes críticos y también para ayudar a garantizar la seguridad del paciente en una organización de cuidados sanitarios.

The Georgian healthcare system is characterized by a large number of clinics. According to the data of 2018, there are 273 inpatient institutions in Georgia, where 39,514 staff members are employed, of which 15,543 are physicians (52.6% of the total number of practicing doctors working in the country) and 12,055 nurses (63.7% of the total number of average medical staff working in the country).1

The health care system must provide the best diagnosis and treatment. However, during operation there is always the possibility of critical incidents, in particular unexpected, unwanted errors that can become harmful for the patient.2,3 A critical incident is defined as an event or circumstance that could have or did lead to harm, loss or damage to people, property, environment, or reputation.4

Patient safety is a specific indicator of the quality of medical care.5 Safety is about protecting the patient from the risk of complications, injury, and adverse outcomes. To improve patient safety, many countries have introduced a Critical Incident Reporting System (CIRS) that makes it easier to identify potential harm to a patient.6 CIRS includes the development of a reporting system in healthcare organizations will focus on error detection, reporting, and training based on these errors, which will not be based on sanctions and punitive actions. CIRS consists of three stages:

Reporting – Medical staff (physician, nurse, etc.) report anonymously, online about the incident and suggest ways and mechanisms to prevent a recurrence of a critical incident in the future.

Assessment – the risk manager, together with the representatives of the relevant department, studies and evaluates critical incidents and proposes solutions.

Feedback – The results of the incident study are published online so other users have the opportunity to get to know with the errors.

CIRS eliminates staff punishment and is a learning process based on the principles of high mutual trust. The system fosters a culture of learning from mistakes among healthcare personnel. To avoid a potentially fatal error, in is necessary to communicate it, talk about it, and learn from it. The position of a Critical Incidents Risk Manager needs to be introduced to implement the CIRS. The effective operation of a CIRS requires anonymity for reporting critical incidents, which is possible using a computer program that will be available to the entire staff of a clinic (with the right to log in using individual passwords).

CIRS have become one of the most common patient safety tools in healthcare organizations in many European countries.7,8 CIRS allows for the critical incidents to be detected and is aimed at improving patient safety, which, in turn, increases the safety of the internal processes of the medical organization.9 Every critical case in a healthcare organization should be reported to the CIRS.10 In addition, the core idea of the CIRS is the recording of each near-miss event identified as a result of self-observations for the purpose of their systematic analysis. This contributes to increasing the level of knowledge of staff.

Different forms of CIRS are used in different countries. In some countries the use of CIRS is mandatory, in others – voluntary. The reporting pattern also differs, that is, what should be reported (for example, critical cases, injuries, patient falls, needle stick injuries, technical problems, or critical incidents involving patients and healthcare professionals). Thus, healthcare organizations in different countries define their own reporting methods in CIRS.11

During the use of CIRS five main problems have been identified: (1) poor processing of information on incidents, (2) lack of consultant involvement, (3) lack of follow-ups, (4) insufficient funding, and (5) little institutional support.12 In addition, transformational leadership, professional and a patient safety culture are needed that encourages effective reporting of critical incidents.13–15

In this regard, it is interesting to share the experience of different countries. In the UK, participation in CIRS is mandatory and accounts for more than 1 million cases reported each year.16 In Switzerland, where the use of CIRS is optional, the University Hospital of Zürich has registered 1400 incidents in 1 year.17 In some countries (e.g. Austria) the CIRS is not yet widely implemented in healthcare organizations. According to a survey conducted in one of the largest hospitals in Austria, only 64.1% of respondents used the CIRS in full.

The purpose of our study is to determine how effectively CIRS is used and how often critical incidents are detected in a hospital, as well as how well healthcare professionals recognize it as a risk management tool.

MethodologyThe study was conducted at the Chapidze Emergency Cardiology Center, which is one of the largest medical establishments in Tbilisi (Georgia). For the evaluation of the deployment of the CIRS all available computerized data base and the medical records of critical incident cases reported to Center were studied for the 2015–2019 period. According to pre-defined data fields, we identified the professional disciplines, number of reported CIRS cases, categories as well as reasons for CIRS cases (related to personal responsibility, patient, organization/team factor/communication/documentation and medical device associated) for the years 2015–2019. All data were analyzed with respect to frequency distribution and proportion (%).

The research design was a descriptive, cross-sectional survey. This was a quantitative approach. Purposive sampling was used to recruit the personnel (managers and clinicians) involved in the CIRS. Participants were invited to take part in the study through email. We sent the link to the web-based survey by e-mail; survey responses were collected anonymously over a 1-month period (June, 2016), and 1 week after sending the link, a reminder e-mail was sent. In total, 196 employees of the center were contacted by e-mail, 181 of which completed and returned a survey (92% response rate). They included doctors (n=52, 29%), nurses (n=95, 52%) and managers (n=34, 19%).

Responders were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire. The questionnaire for this study was developed based on a review of literature. The questionnaire was piloted online prior to the launch of the research, and after validation, minor changes were made as needed.

Prior to starting the research, we received approval from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Caucasus University. Before participating in the research, we obtained informed consent from the personnel. As part of the consent process, personnel were provided with information about the confidentiality of their participation in the survey.

ResultsThe CIRS was first introduced in Georgia in 2015 at the Chapidze Emergency Cardiology Center. Reporting is voluntary and anonymous. Doctors, nurses, administrative and technical staff report incidents anonymously through an electronic reporting system. The hospital has a risk manager who is a clinician. The risk manager, together with the hospital staff, discusses the information about the reported cases at the meeting of the quality committee, evaluates them, and proposes proposals for their solution. Research results are published in an electronic reporting system so that all employees are aware of the errors.

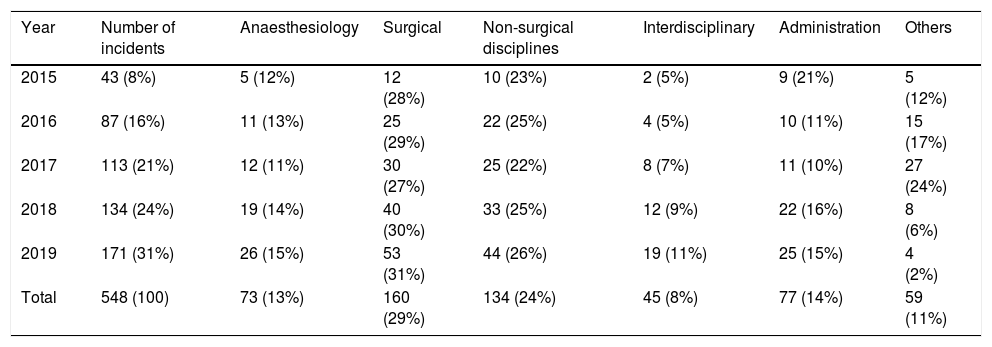

After the introduction of the CIRS, a total of 548 critical incidents were reported in the 2015–2019 period (2015: n=43; 2016: n=87; 2017: n=113; 2018: n=134; 2019: n=171). Critical incidents were mainly registered in surgical (n=160, 29%), non-surgical (n=134, 24%), anaesthesiology (n=73, 13%), and administrative departments (n=77, 14%) (see Table 1).

Cases of CIRS by professional disciplines (n/%).

| Year | Number of incidents | Anaesthesiology | Surgical | Non-surgical disciplines | Interdisciplinary | Administration | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 43 (8%) | 5 (12%) | 12 (28%) | 10 (23%) | 2 (5%) | 9 (21%) | 5 (12%) |

| 2016 | 87 (16%) | 11 (13%) | 25 (29%) | 22 (25%) | 4 (5%) | 10 (11%) | 15 (17%) |

| 2017 | 113 (21%) | 12 (11%) | 30 (27%) | 25 (22%) | 8 (7%) | 11 (10%) | 27 (24%) |

| 2018 | 134 (24%) | 19 (14%) | 40 (30%) | 33 (25%) | 12 (9%) | 22 (16%) | 8 (6%) |

| 2019 | 171 (31%) | 26 (15%) | 53 (31%) | 44 (26%) | 19 (11%) | 25 (15%) | 4 (2%) |

| Total | 548 (100) | 73 (13%) | 160 (29%) | 134 (24%) | 45 (8%) | 77 (14%) | 59 (11%) |

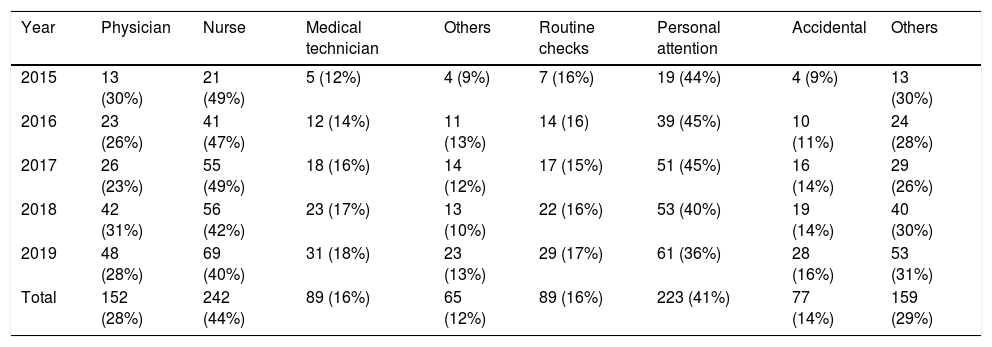

According to the data obtained, the highest number of cases in the CIRS was registered by nurses (n=242, 44%), followed by physicians (n=152, 28%), medical technicians (n=89, 16%) and other personnel (see Table 2). The most common critical incidents were due to lack of personal attention (n=223, 41%), followed by routine checks (n=89, 16%) and accidental (n=77, 14%).

Cases of the CIRS by reporting personnel and cause of occurrence (n/%).

| Year | Physician | Nurse | Medical technician | Others | Routine checks | Personal attention | Accidental | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 13 (30%) | 21 (49%) | 5 (12%) | 4 (9%) | 7 (16%) | 19 (44%) | 4 (9%) | 13 (30%) |

| 2016 | 23 (26%) | 41 (47%) | 12 (14%) | 11 (13%) | 14 (16) | 39 (45%) | 10 (11%) | 24 (28%) |

| 2017 | 26 (23%) | 55 (49%) | 18 (16%) | 14 (12%) | 17 (15%) | 51 (45%) | 16 (14%) | 29 (26%) |

| 2018 | 42 (31%) | 56 (42%) | 23 (17%) | 13 (10%) | 22 (16%) | 53 (40%) | 19 (14%) | 40 (30%) |

| 2019 | 48 (28%) | 69 (40%) | 31 (18%) | 23 (13%) | 29 (17%) | 61 (36%) | 28 (16%) | 53 (31%) |

| Total | 152 (28%) | 242 (44%) | 89 (16%) | 65 (12%) | 89 (16%) | 223 (41%) | 77 (14%) | 159 (29%) |

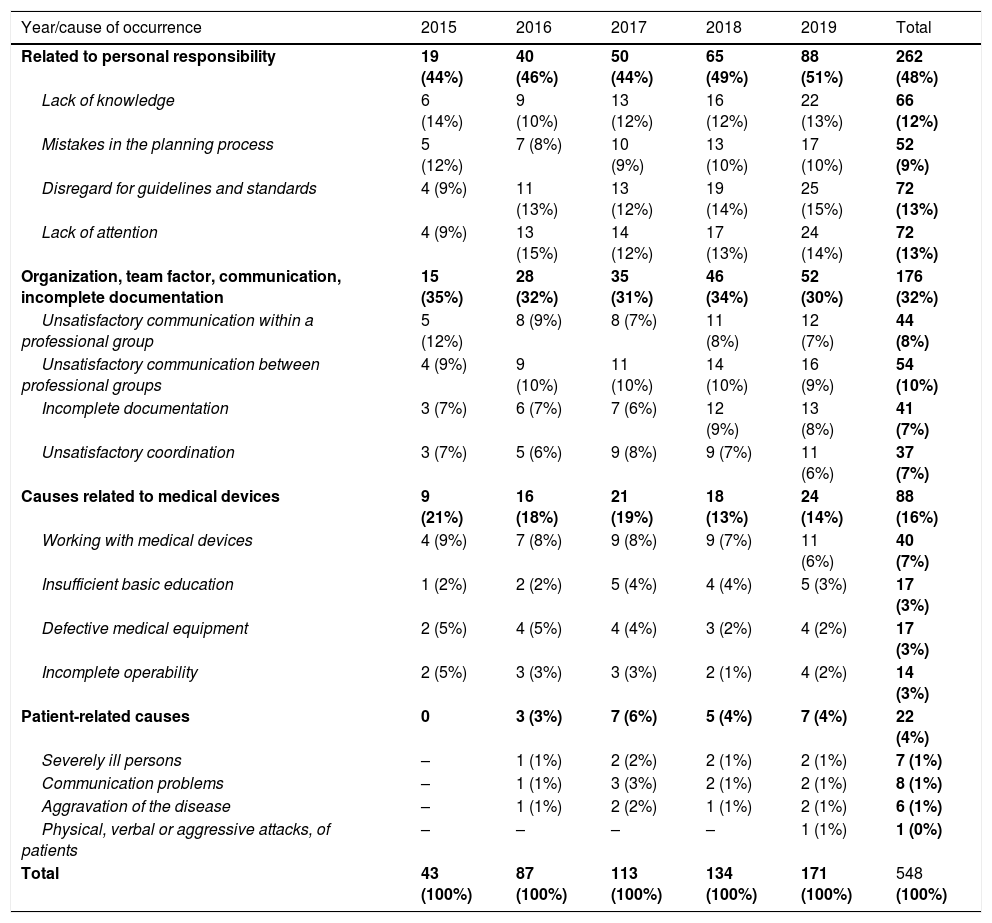

The highest number of critical incidents is related to personal responsibility (48%), followed by errors caused by organization, team factors, communication or incomplete documentation (32%), errors in management of medical devices (16%) and patient-related errors (4%) (see Table 3).

Critical incidents by their cause of occurrence (n/%).

| Year/cause of occurrence | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related to personal responsibility | 19 (44%) | 40 (46%) | 50 (44%) | 65 (49%) | 88 (51%) | 262 (48%) |

| Lack of knowledge | 6 (14%) | 9 (10%) | 13 (12%) | 16 (12%) | 22 (13%) | 66 (12%) |

| Mistakes in the planning process | 5 (12%) | 7 (8%) | 10 (9%) | 13 (10%) | 17 (10%) | 52 (9%) |

| Disregard for guidelines and standards | 4 (9%) | 11 (13%) | 13 (12%) | 19 (14%) | 25 (15%) | 72 (13%) |

| Lack of attention | 4 (9%) | 13 (15%) | 14 (12%) | 17 (13%) | 24 (14%) | 72 (13%) |

| Organization, team factor, communication, incomplete documentation | 15 (35%) | 28 (32%) | 35 (31%) | 46 (34%) | 52 (30%) | 176 (32%) |

| Unsatisfactory communication within a professional group | 5 (12%) | 8 (9%) | 8 (7%) | 11 (8%) | 12 (7%) | 44 (8%) |

| Unsatisfactory communication between professional groups | 4 (9%) | 9 (10%) | 11 (10%) | 14 (10%) | 16 (9%) | 54 (10%) |

| Incomplete documentation | 3 (7%) | 6 (7%) | 7 (6%) | 12 (9%) | 13 (8%) | 41 (7%) |

| Unsatisfactory coordination | 3 (7%) | 5 (6%) | 9 (8%) | 9 (7%) | 11 (6%) | 37 (7%) |

| Causes related to medical devices | 9 (21%) | 16 (18%) | 21 (19%) | 18 (13%) | 24 (14%) | 88 (16%) |

| Working with medical devices | 4 (9%) | 7 (8%) | 9 (8%) | 9 (7%) | 11 (6%) | 40 (7%) |

| Insufficient basic education | 1 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 5 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (3%) | 17 (3%) |

| Defective medical equipment | 2 (5%) | 4 (5%) | 4 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 17 (3%) |

| Incomplete operability | 2 (5%) | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 14 (3%) |

| Patient-related causes | 0 | 3 (3%) | 7 (6%) | 5 (4%) | 7 (4%) | 22 (4%) |

| Severely ill persons | – | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 7 (1%) |

| Communication problems | – | 1 (1%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 8 (1%) |

| Aggravation of the disease | – | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 6 (1%) |

| Physical, verbal or aggressive attacks, of patients | – | – | – | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (0%) |

| Total | 43 (100%) | 87 (100%) | 113 (100%) | 134 (100%) | 171 (100%) | 548 (100%) |

The study has shown that among the individual causes of critical incidents, the most common are disregard for guidelines and standards (13%), inattention (13%), lack of knowledge (12%), mistakes in the planning process (9%). Critical incidents related to organization, team factor, communication, and incomplete documentation are mainly caused by unsatisfactory communication between professional groups (10%), unsatisfactory communication within the professional group (8%), incomplete documentation (7%), and poor coordination (7%). Among the reasons associated with medical devices, the following should be noted: working with medical equipment (7%), insufficient basic education (3%), defective medical equipment (3%), incomplete operability (3%). Patient-related causes include severely ill persons (1%), communication problems (1%), aggravation of the disease (1%), physical, verbal or aggressive attacks of patients (see Table 3).

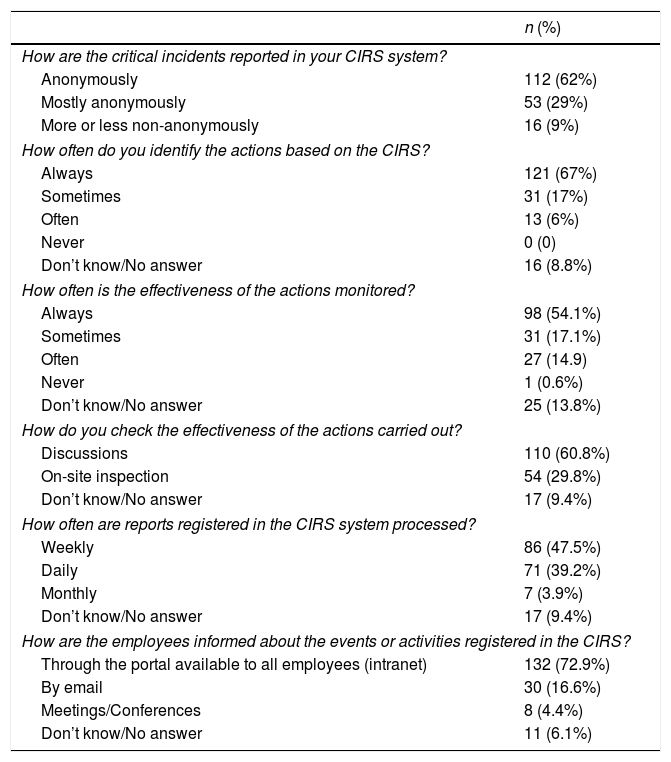

The survey results showed that reporting of critical incidents is mostly anonymous (62%), although some of the reporting of critical incidents more or less non-anonymously (9%) is also possible. Hospital's personnel often follow the guidelines of the CIRS (67%), while 54% believe their effectiveness is always monitored. The effectiveness of the implemented measures is mainly verified through discussion (60.8%) and on-site inspections (29.8%). Reports registered in the CIRS are mostly processed on a weekly basis (47.5%) and daily (39.2%). Employees are informed about the events or activities registered in the CIRS is mainly done through the portal available to everyone – intranet (72.9%) (Table 4).

CIRS survey results.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| How are the critical incidents reported in your CIRS system? | |

| Anonymously | 112 (62%) |

| Mostly anonymously | 53 (29%) |

| More or less non-anonymously | 16 (9%) |

| How often do you identify the actions based on the CIRS? | |

| Always | 121 (67%) |

| Sometimes | 31 (17%) |

| Often | 13 (6%) |

| Never | 0 (0) |

| Don’t know/No answer | 16 (8.8%) |

| How often is the effectiveness of the actions monitored? | |

| Always | 98 (54.1%) |

| Sometimes | 31 (17.1%) |

| Often | 27 (14.9) |

| Never | 1 (0.6%) |

| Don’t know/No answer | 25 (13.8%) |

| How do you check the effectiveness of the actions carried out? | |

| Discussions | 110 (60.8%) |

| On-site inspection | 54 (29.8%) |

| Don’t know/No answer | 17 (9.4%) |

| How often are reports registered in the CIRS system processed? | |

| Weekly | 86 (47.5%) |

| Daily | 71 (39.2%) |

| Monthly | 7 (3.9%) |

| Don’t know/No answer | 17 (9.4%) |

| How are the employees informed about the events or activities registered in the CIRS? | |

| Through the portal available to all employees (intranet) | 132 (72.9%) |

| By email | 30 (16.6%) |

| Meetings/Conferences | 8 (4.4%) |

| Don’t know/No answer | 11 (6.1%) |

The CIRS is introduced in only one hospital in Georgia. From 2015 to 2019, at the Chapidze Emergency Cardiology Center, the number of incidents recorded in the CIRS increased from 43 to 548, or 13 times. The trainings carried out for the personnel contributed to the annual increase in the number of incidents reported in the CIRS.

The annual increase in the number of reported critical incidents suggests that there are actually more cases, so the number of cases identified in the CIRS is only a small fraction of the actual number of critical incidents. However, due to the fact that the CIRS in Georgia operates only at the Chapidze Emergency Cardiology Center, it is impossible to compare it with medical organizations neither within the country nor in European countries.

The study shows that critical incidents are most often reported by nurses, but doctor participation is growing steadily from year to year. We suggest that continuous training on using CIRS needs a certain period to attract all personnel.

The study shows that the occurrence of critical incidents is mainly associated with the personal responsibility of the staff, namely, with a lack of attention and disregard for existing guidelines and standards, lack of competence. The same results have been obtained in other studies.18 Examples of negligence and disregard for standards include the missing or wrong usage of the surgical safety checklist, national and international surgical safety guidelines/protocols, violations of hygiene norms. Failure to comply with guidelines may be due to inadequate, incomplete training of personnel in its principles. In this regard, it is necessary to raise the level of awareness of employees. Inattention can be a sign of stress, lack of knowledge of routine procedures.

Unsatisfactory oral, written, or other form of communication between groups of health care workers also played an important role in the occurrence of critical incidents. The same results have been obtained in other studies.19 However, according to other studies, the occurrence of critical incidents is mainly related to medical devices, clinical practice and pharmaceuticals.20

CIRS can be seen as a positive safety enhancement tool that can change the attitude of personnel to risks, increase their vigilance and attention, and awareness of best practices. The study showed that hospital staff adheres to the recommendations of the CIRS, and the effectiveness of the measures carried out is mainly determined through discussion and on-site inspections.

The main obstacle to reporting critical incidents in the CIRS can be a fear of social pressure or punishment in cases where people who have reported the incidents can be identified.21,22 The concepts of confidence and trust permeated the data, with particular reference to the anonymous and confidential handling of reports.23 In this regard, important are those socio-cultural aspects of medical professionalism that emphasize the significance of collegiality.24

There is yet no real improvement or routine use of CIRS in hospitals throughout the country. One reason could be an insufficient announcement and explanation of the safety reporting system. Another reason may be the fear in personal that any reported incident would cause a backlash disciplinary by the employer.25 Whether incident data are disclosable in potential prosecutions, may also play a role.26 Solution to this problem is to make reports anonymous so that individual clinicians cannot be identified. There is no legal provision to protect reporting people.

CIRS can play an important role in a learning organization by providing the information needed and serving as the basis of a standardized process taken to reduce the number of critical incidents. To do this, all employees must have access to CIRS accounts via intranet or email. The study showed that the employees are informed about the incidents or measures registered in the CIRS mostly through an intranet – a portal accessible for everyone. In addition, periodic collection of critical incidents statistics is required to provide relevant information to hospital managers. Research has shown that reports sent to the CIRS are mostly processed weekly and daily.

This study is very important as there has been no previously published data on CIRS in Georgia. This is the first useful mirror that shows the actual condition of the patient safety and reporting systems in hospitals. In our view, this will shed light on the future establishments of CIRS and improvements.

In summary, our results suggest that systematic analysis of critical incidents is important to reduce medical errors and raise awareness. Research has shown that most of the critical incidents arise from non-adherence to guidelines and standards. Therefore, great attention should be paid to issues such as hand hygiene, the correct application of surgical safety standards. Continuous training of medical personnel is necessary for the further development of the CIRS.

CIRS can be seen as an effective clinical risk management tool that can be used to identify potential sources of critical incidents and help ensure patient safety at a healthcare organization. Categorization of critical incidents in accordance with threats and predetermined reasons helps to determine the directions of the medical organization's activities and, respectively, its development.

Structural and procedural changes in critical care, training for staff, continuous medical education are needed, and the effectiveness, efficiency and efficacy of these measures remain to be evaluated in the future.

Thus, it is desirable to widely introduce the CIRS in medical organizations of Georgia. As the reporting system is set up, future studies will be required either for the promotion, assessment and supervision of CIRS.

EthicsThe study protocol was approved by the local Bioethics Committee (No. 2020-32).

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.