To analyze the prevalence of dating violence (DV) and its relationship with states of depression, anxiety, and stress in young Andalusian university students.

MethodCross-sectional descriptive quantitative study in 8 public universities in Andalusia. Data collection was carried out from September to November 2020 through a self-administered questionnaire that included sociodemographic variables and variables related to dating violence, depression, anxiety, and stress. For the analysis of the data, descriptive and nonparametric tests were performed through the U Mann–Whitney and Spearman Rho for the relationship between variables.

ResultsThousand ninety-one young university students from Andalusia participated. The most prevalent DV was psychological, including behaviors related to cyberbullying, control-surveillance and psychoemotional (68.42–42.90%), followed by sexual (16.68–3.57%) and finally physical (5.60–1.92%). Statistically significant differences were shown according to sex and DV, where girls scored higher in being victims of behaviors related to cyberbullying, control-surveillance and sexual, and boys in perpetrating psycho-emotional, physical and sexual violence. All types of DV showed significant and positive correlations with depression, anxiety, and stress, except physical DV perpetrated with stress.

ConclusionsThe high prevalence of DV and its relationship with mental health show the importance of conducting research on this line in the educational field, since it is a space that guarantees egalitarian relationships and promotes health.

Analizar la prevalencia de la violencia en el noviazgo (VN) y su relación con los estados de depresión, ansiedad y estrés en jóvenes universitarios andaluces.

MétodoEstudio cuantitativo descriptivo transversal en 8 universidades públicas de Andalucía. La recogida de datos se realizó de septiembre a noviembre de 2020 través de un cuestionario autoadministrado que incluía variables sociodemográficas y variables relacionada con la violencia en el noviazgo, depresión, ansiedad y estrés. Para el análisis de los datos se realizó un descriptivo y pruebas no paramétricas a través de la U de Mann–Whitney y rho de Spearman para la relación entre variables.

ResultadosParticiparon 1.091 jóvenes universitarios andaluces. La VN más prevalente fue la psicológica, incluyendo conductas relacionadas con el ciberacoso, control-vigilancia y psicoemocional (68,42–42,90%), seguida de la sexual (16,68–3,57%) y por último la física (5,60–1,92%). Se mostraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en función del sexo y la VN, donde las chicas puntuaron más alto en ser víctimas de conductas relacionadas con el ciberacoso, control-vigilancia y sexual, y los chicos en perpetrar violencia de tipo psicoemocional, física y sexual. Todos los tipos de VN evidenciaron correlaciones significativas y positivas con la depresión, ansiedad y estrés, menos la VN física perpetrada con el estrés.

ConclusionesLa alta prevalencia de VN y su relación con la salud mental muestran la importancia de realizar investigaciones en esta línea en el ámbito educativo, ya que es un espacio garante de relaciones igualitarias y promotor de la salud.

What is known?

Dating violence is a priority public health issue that affects psychological, physical and sexual health.

What does it contributes?

This study has enabled us to pinpoint the prevalence of dating violence, consider its multidimensionality, and analyse its relationship with depression, anxiety and stress in the university context, as well as considering health promoting areas to contribute to the design of actions or protocols to improve the relationships and the health of young people.

Dating violence (DV) is a complex phenomenon, composed of micro- and macro-level social factors.1 It comprises a set of attitudes, behaviours and relationship styles where there is violence, threat or intentional provocation of physical, emotional, verbal, psychological and sexual harm, as well as control of a partner through coercive tactics. This occurs in young or adolescent couples who do not have a cohabiting relationship, children or binding economic relationships1–3 and is considered a priority public health issue.1

Recent research on university populations shows that the most prevalent form of DV is psychological, followed by physical and sexual violence.2–4 In relation to directionality, recent research highlights two positions that analyse the dynamics of intimate partner violence.5 On the one hand, there is a unidirectional perspective based on feminist theory that considers males as the sole perpetrators of violence, based on a patriarchal focus where violence is exercised against women simply because they are women, and due to their inferior position with respect to the dominant gender, men.5 In contrast, we would adopt a bidirectional approach, where both men and women may take on the role of victims or perpetrators.5 In relation to the latter position, the violence exercised by women would correspond to a process of self-defence or resistance according to feminist theory.5,6

In relation to health, the fact of having suffered a situation of DV gives rise to negative physical and psychological results. With regard to the psychological consequences, which are the most prevalent at this age, we have been able to highlight higher rates of behavioural disorders, anxiety and depression,7 this even triggering symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder,8 eating disorders9 and even suicide attempts, which are more likely when physical and sexual violence are also present.10,11 In addition, DV has been associated with victims having poorer social relationships, possibly becoming hostile and indifferent, and reducing contacts with friends and family. This leads to social isolation,1 which is often linked to alcohol and drug abuse12 and poor work/school performance.2,3

Preventing and detecting DV should be a priority for several reasons. The first is that a high percentage of adolescents and young people are often unaware that they are in a violent dating relationship. This may be because some violent behaviours are more subtle and in many cases normalised5, largely influenced by the myths of romantic love.13 The second reason is that only a low percentage of those who experience DV actually seek help.5 Finally, DV can be a precursor to intimate partner violence in adulthood.12 In addition, dating violence has been less researched than intimate partner violence in adulthood, thus the causes, behaviours or inappropriate precursors that hinder a healthy dating relationship go unnoticed.

Another aspect to be considered is the role of the nurse in the approach to violence against children in the school setting In this regard, the role of the school nurse - who can undertake specific assessments of DV and intervene adopting a youth-centred focus - is of particular importance. In addition, the school nurse is a link between the school and health services or other support resources.14

Thus, within the university context, as an environment that promotes health and guarantees egalitarian relationships,15 it is essential to ascertain what the dating relationships of young students are like and how these relationships are influencing their mental health, in order to be able to act in time and prevent them. Moreover, as far as the authors of this study are aware, there is no research that analyses dating violence perpetrated and experienced in a multidimensional form, and its relationship with mental health as a whole. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyse the prevalence of DV and its relationship with depression, anxiety and stress in young Andalusian university students.

MethodDesignCross-sectional descriptive observational study.

Population and scope of the studyData was collected between 28th September and 16th November 2020 in the Andalusian University System. The study included students from 8 public universities in Andalusia (Almeria, Cadiz, Cordoba, Granada, Huelva, Jaen, Malaga and Seville) on degree courses in different areas of knowledge (arts and humanities, health sciences, social sciences, law and pure sciences).

The sample size was calculated on the basis of the total number of students enrolled on undergraduate degree courses in the Andalusian university system in 2019/2020 (203,595 students), with a confidence level of 95% and precision (margin of error) of 3%, obtaining an estimated sample size of 1,062 students. The sample was selected by means of non-probabilistic convenience sampling, through students’ participation in an awareness-raising course entitled “Promoting healthy relationships in Andalusian university youth. Prevention of Gender Violence”, funded by the Andalusian Youth Institute.16 The course was publicised in the different Andalusian universities through the office of the Dean, the teaching staff, the Equality Unit and the Health Promotion Unit. Those interested accepted to take part on a voluntary basis.

The programme was designed by teaching staff from the Nursing Department with training in Gender-based Violence (GBV) at the University of Seville. The content addressed 5 thematic blocks: 1. Dating violence and gender-based violence (DV and GBV); 2. Stereotypes, myths of romantic love, sexism; 3. The cycle of DV; 4. Violence through the new ICTs (information and communication technologies); 5. Repercussions on health.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: students of either sex, aged between 18–24 years old, enrolled on a degree course at one of the public universities in Andalusia and who had gone through at least one relationship with a partner. Exclusion criteria: language difficulties.

Variables and instrumentsThe variables designed in line with the aim of the study were sociodemographic (sex, age, nationality, geographical area of origin, university, degree course, average time in a relationship, number of partners in the last year, whether or not they had a partner at the time of submitting the questionnaire and whether or not they were currently living with their partner) as well as variables related to the existence of DV and depression, stress and anxiety, through validated scales.

The short, updated version of the Multidimensional Scale of Dating Violence (MSDV)4 was used to analyse DV- the MSDV 2.0.17 This scale had previously been validated in the sample for this research and consisted of two subscales (victimisation and perpetration), with 18 items each, which were grouped into 5 dimensions, as follows: cyberbullying, control and/or surveillance, psycho-emotional, physical and sexual. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient) for the total victimization subscale was .88 and .80 for the perpetration subscale. Each item was scored on a Likert scale with 5 response options from 1 to 5, where the higher the score, the more the violence suffered or perpetrated. For each dimension, minimum and maximum ranges were set, thus for cyberbullying and the psycho-emotional dimension this was 3–15; for control and/or surveillance and the sexual dimensions, between 5–25; and for the physical dimension, 2–10.

In the analysis of depression, anxiety and stress, the reduced Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) was used, validated in young Spanish university students by Fonseca et al. 2010.18 This scale is a self-administered instrument consisting of three subscales that assess various emotional states: depression, anxiety and stress in a young, non-clinical population. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient) reported for the total scale was .90, and 0.80; .73 and .81 for the depression, anxiety and stress subscales respectively. Its 21 items were evaluated in accordance with a Likert-type scale, with four response options from 0 to 3, where higher scores indicated poorer states of health and each of its three dimensions had minimum and maximum ranges from 0–21.

Data collectionData was collected by means of a self-administered online questionnaire using the Google Forms® platform since the pandemic situation arising due to COVID-19 did not permit face-to-face attendance. The questionnaires were sent out through the awareness-raising course, and the questionnaire was completed voluntarily by young university students after attending the training.

The questionnaire was accompanied by an introductory text providing brief information on the aim of the study and the previously defined variables. It was designed ad hoc by members of the research team (n = 4) with a teaching and research profile in DV, health care and psychometrics. To ensure the internal validity of the results obtained, the course coordinator was responsible for collecting the data and its subsequent filtering. A protocol and systematisation scheme was designed for handling the questionnaires; clear instructions were drawn up for the completion of the instruments, and it was ensured that the questionnaire application at the different universities was run under similar conditions, with exhaustive control throughout the data collection procedure.

Data analysisThe normality of the data distribution was calculated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In the present study, the data was found not to follow the normal distribution. Descriptive statistics were used in the univariate analysis. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were calculated for quantitative variables, and absolute and relative frequencies and confidence intervals were calculated for qualitative variables. In the bivariate analysis, Spearman’s Rho was used for correlations (hypothesis testing between quantitative variables: DV, depression, anxiety and stress). The following correlation ranges were considered: .91 to 1.00 perfect; .76 to .90 very strong; .51 to .75 considerable; .11 to .50 average; .01 to .10 weak and .00 no correlation.19 The Mann–Whitney U test was used for the analysis of dichotomous qualitative variables and quantitative variables (sex and DV) and the effect size was calculated using the probability of superiority (PS) ratio, establishing the following values: no effect (PS ≤ 0.0); small (PS ≤ 0.56); medium (PS: .57–.70) and large (PS ≥ .71)20. The confidence level was set at 95%, so statistical significance corresponded throughout the study to p < .05. Statistical analysis was performed with the IBM-SPSS Statistics software package version 24.0 (IBM Corp©).

Ethical considerationsThe research was approved by the ethics committee of the Virgen Macarena and Virgen del Rocío Hospitals (Code VNRS_18) and the anonymity of all participants, who signed the informed consent form, was guaranteed. The ethical considerations of the Declaration of Helsinki were respected and the confidentiality of the data was guaranteed as stipulated under Organic Law 3/2018 of 5th December, on the Protection of Personal Data and guarantee of digital rights.

ResultsCharacteristics of the sampleOf the 1091 young university students, 85% of the sample were women and 15% were men. A total of 96% (1051) were Spanish nationality and 4% (40) were other nationalities (Italian, Brazilian, Moroccan and Portuguese). Only 9% lived in rural areas. The median age was 20 years (IQR = 2).

As regards the university they belonged to, students were enrolled as follows: University of Seville (29.2%), University of Cordoba (17.1%), University of Jaen (13.7%), University of Malaga (14.3%), University of Huelva (11.3%), University of Granada (5%), University of Cadiz (5%) and University of Almeria (4.4%) and the students were studying different areas of knowledge: Health Sciences (49.3%), Social Sciences and Law (44.9%), Arts and Humanities (5.3%), Engineering and Architecture (.4%) and Pure Sciences (.1%).

The median duration of a dating relationship was 18 months (IQR = 27). A total of 81.7% were in a dating relationship at the time of submitting the questionnaire and only 5% were living together.

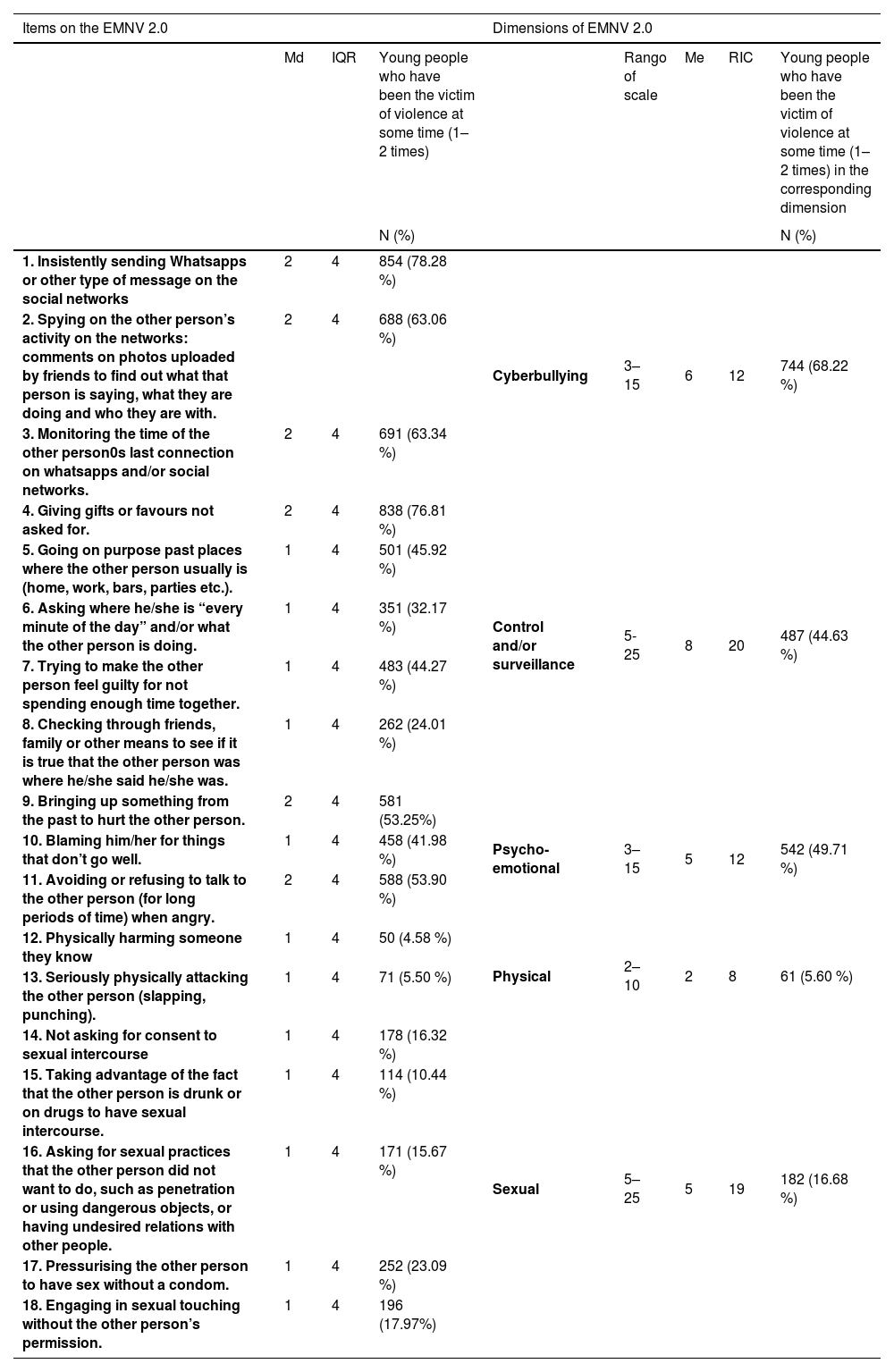

Prevalence of DV and its relation to depression, anxiety and stressIn DV experienced, the most prevalent behaviours with a frequency of at least once or twice were those related to cyberbullying (68.22%), followed by psycho-emotional behaviours (49.71%), those related to control and surveillance (44.63%), sexual (16.68%) and finally physical (5.60%) (Table 1). It was noteworthy that acts related to physical and sexual violence suffered were at least four times the rates recorded for violence perpetrated in the same behaviours, the most prevalent being “pressurising to have sex without a condom”.

Prevalence of dating violence suffered.

| Items on the EMNV 2.0 | Dimensions of EMNV 2.0 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Md | IQR | Young people who have been the victim of violence at some time (1–2 times) | Rango of scale | Me | RIC | Young people who have been the victim of violence at some time (1–2 times) in the corresponding dimension | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | |||||||

| 1. Insistently sending Whatsapps or other type of message on the social networks | 2 | 4 | 854 (78.28 %) | Cyberbullying | 3–15 | 6 | 12 | 744 (68.22 %) |

| 2. Spying on the other person’s activity on the networks: comments on photos uploaded by friends to find out what that person is saying, what they are doing and who they are with. | 2 | 4 | 688 (63.06 %) | |||||

| 3. Monitoring the time of the other person0s last connection on whatsapps and/or social networks. | 2 | 4 | 691 (63.34 %) | |||||

| 4. Giving gifts or favours not asked for. | 2 | 4 | 838 (76.81 %) | Control and/or surveillance | 5-25 | 8 | 20 | 487 (44.63 %) |

| 5. Going on purpose past places where the other person usually is (home, work, bars, parties etc.). | 1 | 4 | 501 (45.92 %) | |||||

| 6. Asking where he/she is “every minute of the day” and/or what the other person is doing. | 1 | 4 | 351 (32.17 %) | |||||

| 7. Trying to make the other person feel guilty for not spending enough time together. | 1 | 4 | 483 (44.27 %) | |||||

| 8. Checking through friends, family or other means to see if it is true that the other person was where he/she said he/she was. | 1 | 4 | 262 (24.01 %) | |||||

| 9. Bringing up something from the past to hurt the other person. | 2 | 4 | 581 (53.25%) | Psycho-emotional | 3–15 | 5 | 12 | 542 (49.71 %) |

| 10. Blaming him/her for things that don’t go well. | 1 | 4 | 458 (41.98 %) | |||||

| 11. Avoiding or refusing to talk to the other person (for long periods of time) when angry. | 2 | 4 | 588 (53.90 %) | |||||

| 12. Physically harming someone they know | 1 | 4 | 50 (4.58 %) | Physical | 2–10 | 2 | 8 | 61 (5.60 %) |

| 13. Seriously physically attacking the other person (slapping, punching). | 1 | 4 | 71 (5.50 %) | |||||

| 14. Not asking for consent to sexual intercourse | 1 | 4 | 178 (16.32 %) | Sexual | 5–25 | 5 | 19 | 182 (16.68 %) |

| 15. Taking advantage of the fact that the other person is drunk or on drugs to have sexual intercourse. | 1 | 4 | 114 (10.44 %) | |||||

| 16. Asking for sexual practices that the other person did not want to do, such as penetration or using dangerous objects, or having undesired relations with other people. | 1 | 4 | 171 (15.67 %) | |||||

| 17. Pressurising the other person to have sex without a condom. | 1 | 4 | 252 (23.09 %) | |||||

| 18. Engaging in sexual touching without the other person’s permission. | 1 | 4 | 196 (17.97%) | |||||

Note: Md: median; IQR: interquartile range; N: number of participants.

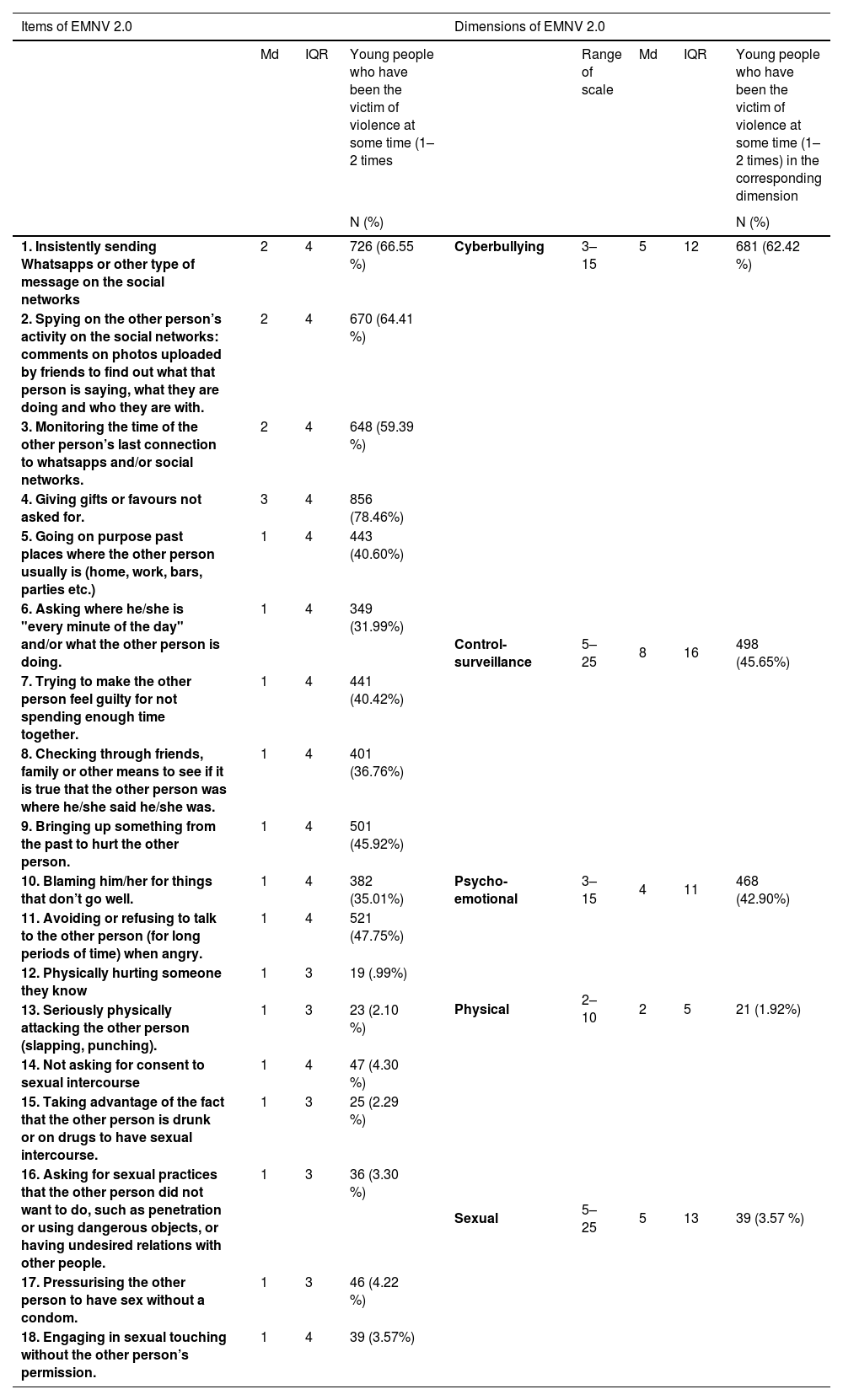

In perpetrated DV, the most prevalent behaviours were those related to cyberbullying (62.42%) followed by control and surveillance (45.65%); psycho-emotional (42.90%); sexual (3.57%); and finally, physical (1.92%) (Table 2). In comparison with DV experienced, the scores obtained were lower in all the behaviours analysed, except in two of these, related to control and vigilance: “Giving unrequested gifts or doing favours”, “Checking, through friends, family or other means, it was true that the other person was where they said they were”.

Prevalence of dating violence perpetrated.

| Items of EMNV 2.0 | Dimensions of EMNV 2.0 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Md | IQR | Young people who have been the victim of violence at some time (1–2 times | Range of scale | Md | IQR | Young people who have been the victim of violence at some time (1–2 times) in the corresponding dimension | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | |||||||

| 1. Insistently sending Whatsapps or other type of message on the social networks | 2 | 4 | 726 (66.55 %) | Cyberbullying | 3–15 | 5 | 12 | 681 (62.42 %) |

| 2. Spying on the other person’s activity on the social networks: comments on photos uploaded by friends to find out what that person is saying, what they are doing and who they are with. | 2 | 4 | 670 (64.41 %) | |||||

| 3. Monitoring the time of the other person’s last connection to whatsapps and/or social networks. | 2 | 4 | 648 (59.39 %) | |||||

| 4. Giving gifts or favours not asked for. | 3 | 4 | 856 (78.46%) | Control-surveillance | 5–25 | 8 | 16 | 498 (45.65%) |

| 5. Going on purpose past places where the other person usually is (home, work, bars, parties etc.) | 1 | 4 | 443 (40.60%) | |||||

| 6. Asking where he/she is "every minute of the day" and/or what the other person is doing. | 1 | 4 | 349 (31.99%) | |||||

| 7. Trying to make the other person feel guilty for not spending enough time together. | 1 | 4 | 441 (40.42%) | |||||

| 8. Checking through friends, family or other means to see if it is true that the other person was where he/she said he/she was. | 1 | 4 | 401 (36.76%) | |||||

| 9. Bringing up something from the past to hurt the other person. | 1 | 4 | 501 (45.92%) | Psycho-emotional | 3–15 | 4 | 11 | 468 (42.90%) |

| 10. Blaming him/her for things that don’t go well. | 1 | 4 | 382 (35.01%) | |||||

| 11. Avoiding or refusing to talk to the other person (for long periods of time) when angry. | 1 | 4 | 521 (47.75%) | |||||

| 12. Physically hurting someone they know | 1 | 3 | 19 (.99%) | Physical | 2–10 | 2 | 5 | 21 (1.92%) |

| 13. Seriously physically attacking the other person (slapping, punching). | 1 | 3 | 23 (2.10 %) | |||||

| 14. Not asking for consent to sexual intercourse | 1 | 4 | 47 (4.30 %) | Sexual | 5–25 | 5 | 13 | 39 (3.57 %) |

| 15. Taking advantage of the fact that the other person is drunk or on drugs to have sexual intercourse. | 1 | 3 | 25 (2.29 %) | |||||

| 16. Asking for sexual practices that the other person did not want to do, such as penetration or using dangerous objects, or having undesired relations with other people. | 1 | 3 | 36 (3.30 %) | |||||

| 17. Pressurising the other person to have sex without a condom. | 1 | 3 | 46 (4.22 %) | |||||

| 18. Engaging in sexual touching without the other person’s permission. | 1 | 4 | 39 (3.57%) | |||||

Note: Md: median; IQR: interquartile range; N: number of participants.

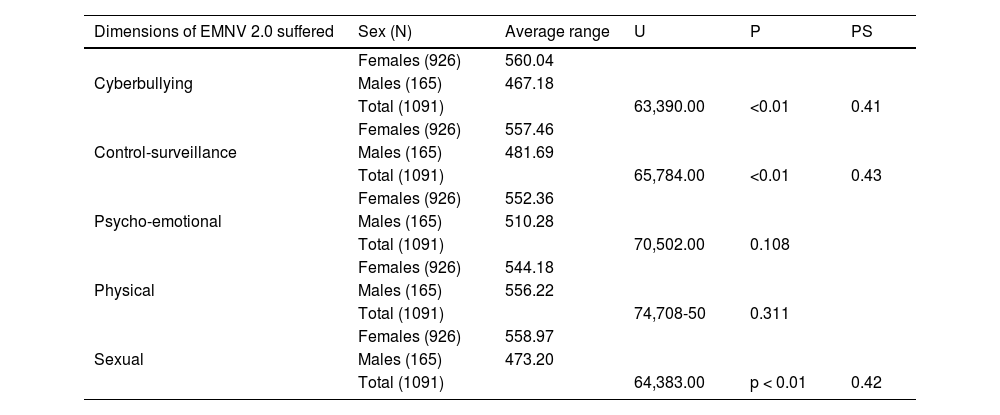

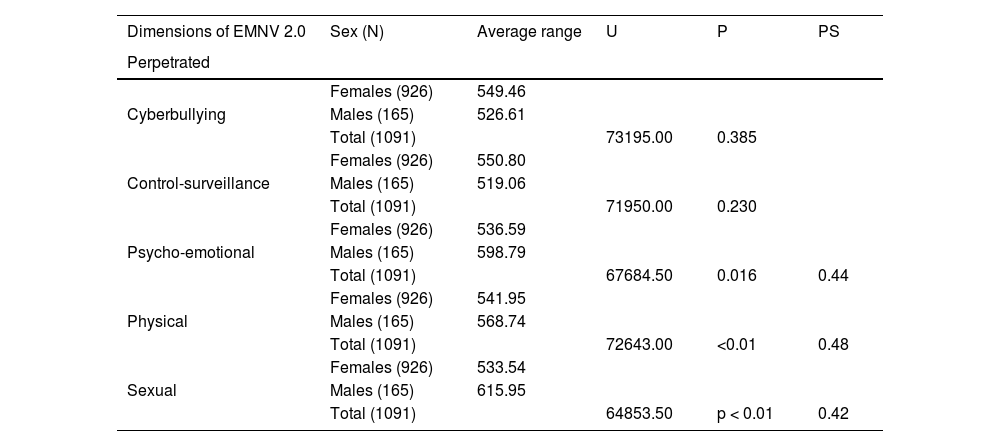

With regard to gender differences, statistically significant differences were found in behaviours related to cyberbullying (U = 63390.00; p < .01), acts of control and/or surveillance (U = 65784.00; p < .01) and sexual behaviours (U = 64383.00 p < .01), where females scored significantly higher as victims of all of these (Table 3). In addition, statistically significant sex differences were found in the psycho-emotional (U = 67684.50; p = .016), physical (U = 72643.00; p < .01) and sexual (U = 64853.50; p < .01) categories of perpetrated DV, where these behaviours were mostly those of men. However, the statistically significant differences found should be considered with caution as they show a small size effect (PS ≤ .56) (Table 4).

Differences depending on gender and dating violence suffered (EMVN 2.0).

| Dimensions of EMNV 2.0 suffered | Sex (N) | Average range | U | P | PS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyberbullying | Females (926) | 560.04 | |||

| Males (165) | 467.18 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 63,390.00 | <0.01 | 0.41 | ||

| Control-surveillance | Females (926) | 557.46 | |||

| Males (165) | 481.69 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 65,784.00 | <0.01 | 0.43 | ||

| Psycho-emotional | Females (926) | 552.36 | |||

| Males (165) | 510.28 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 70,502.00 | 0.108 | |||

| Physical | Females (926) | 544.18 | |||

| Males (165) | 556.22 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 74,708-50 | 0.311 | |||

| Sexual | Females (926) | 558.97 | |||

| Males (165) | 473.20 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 64,383.00 | p < 0.01 | 0.42 |

Note: N: sample size; U: Mann–Whitney U test; P: P value (P < 0.05); PS: Probability of Superiority (size of effect).

Differences depending on gender and dating violence perpetrated (EMVN 2.0).

| Dimensions of EMNV 2.0 | Sex (N) | Average range | U | P | PS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perpetrated | |||||

| Cyberbullying | Females (926) | 549.46 | |||

| Males (165) | 526.61 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 73195.00 | 0.385 | |||

| Control-surveillance | Females (926) | 550.80 | |||

| Males (165) | 519.06 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 71950.00 | 0.230 | |||

| Psycho-emotional | Females (926) | 536.59 | |||

| Males (165) | 598.79 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 67684.50 | 0.016 | 0.44 | ||

| Physical | Females (926) | 541.95 | |||

| Males (165) | 568.74 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 72643.00 | <0.01 | 0.48 | ||

| Sexual | Females (926) | 533.54 | |||

| Males (165) | 615.95 | ||||

| Total (1091) | 64853.50 | p < 0.01 | 0.42 |

Note: N: sample size; U: Mann–Whitney U test; P:P value (P < 0.05); PS: Probability of Superiority (size of effect).

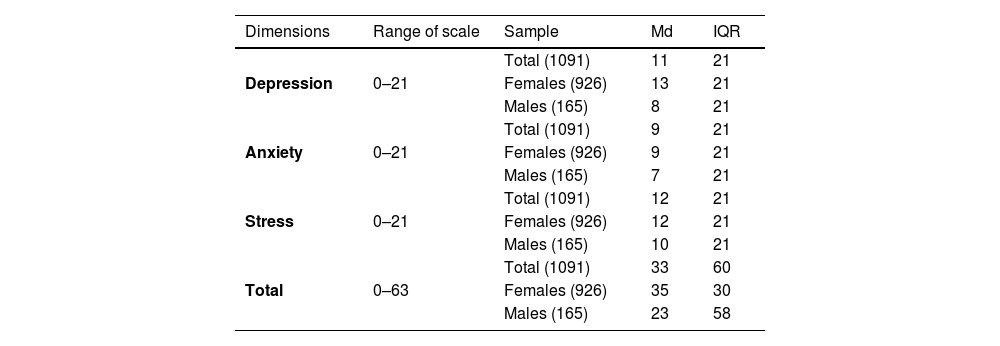

Regarding states of mental health, the most prevalent was stress (md = 12), followed by depression (md = 11) and anxiety (md = 9), where the girls scored higher than the boys (Table 5).

Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in young people.

| Dimensions | Range of scale | Sample | Md | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 0–21 | Total (1091) | 11 | 21 |

| Females (926) | 13 | 21 | ||

| Males (165) | 8 | 21 | ||

| Anxiety | 0–21 | Total (1091) | 9 | 21 |

| Females (926) | 9 | 21 | ||

| Males (165) | 7 | 21 | ||

| Stress | 0–21 | Total (1091) | 12 | 21 |

| Females (926) | 12 | 21 | ||

| Males (165) | 10 | 21 | ||

| Total | 0–63 | Total (1091) | 33 | 60 |

| Females (926) | 35 | 30 | ||

| Males (165) | 23 | 58 |

Note: Md: median; IQR: interquartile range.

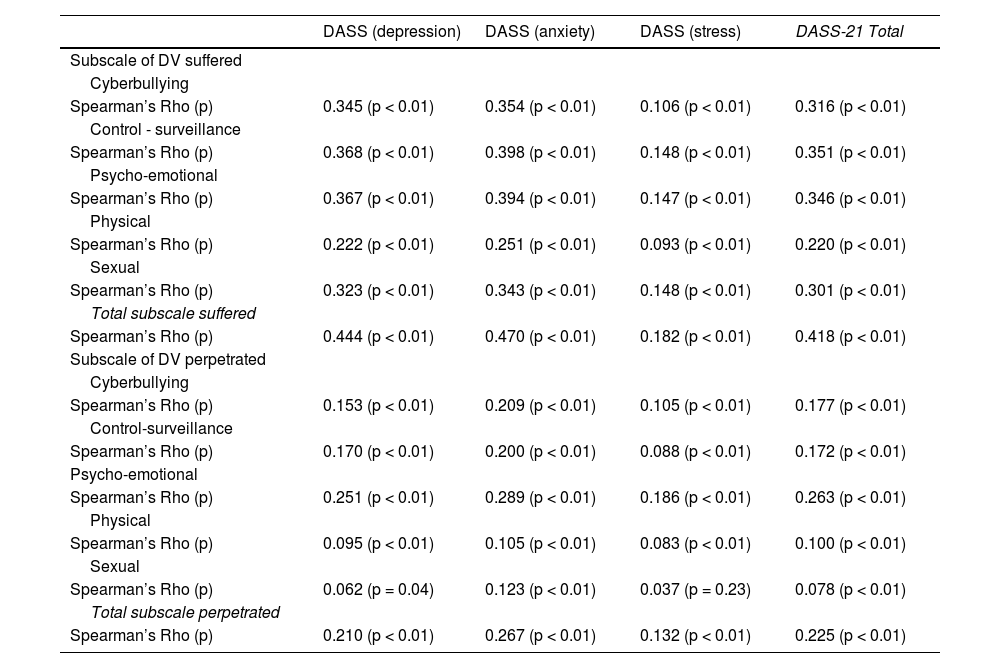

Correlational analysis showed positive and significant relationships for total DV experienced with depression (Rho = .444; p < .01), anxiety (Rho = .470; p < .01) and stress (r = .18; p < .01). The dimensions that showed the strongest relationship was control and/or surveillance with anxiety (Rho = 0.398; p < 0.01) and psycho-emotional with anxiety (Rho = .394; p < .01). Also, for total perpetrated DV, positive and significant correlations were obtained with depression (Rho = .210; p < .01), anxiety (Rho = .267; p < .01) and stress (Rho = .132; p < .01), but these were lower. For both subscales, the correlation ranged from medium to weak. The only dimension that showed no significant correlation was physical violence perpetrated in relation to stress (Table 6).

Spearman’s Rho correlation coefficients between DV (EMVN 2.0) and Depression, Anxiety and Stress (DASS-21).

| DASS (depression) | DASS (anxiety) | DASS (stress) | DASS-21 Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscale of DV suffered | ||||

| Cyberbullying | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.345 (p < 0.01) | 0.354 (p < 0.01) | 0.106 (p < 0.01) | 0.316 (p < 0.01) |

| Control - surveillance | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.368 (p < 0.01) | 0.398 (p < 0.01) | 0.148 (p < 0.01) | 0.351 (p < 0.01) |

| Psycho-emotional | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.367 (p < 0.01) | 0.394 (p < 0.01) | 0.147 (p < 0.01) | 0.346 (p < 0.01) |

| Physical | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.222 (p < 0.01) | 0.251 (p < 0.01) | 0.093 (p < 0.01) | 0.220 (p < 0.01) |

| Sexual | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.323 (p < 0.01) | 0.343 (p < 0.01) | 0.148 (p < 0.01) | 0.301 (p < 0.01) |

| Total subscale suffered | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.444 (p < 0.01) | 0.470 (p < 0.01) | 0.182 (p < 0.01) | 0.418 (p < 0.01) |

| Subscale of DV perpetrated | ||||

| Cyberbullying | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.153 (p < 0.01) | 0.209 (p < 0.01) | 0.105 (p < 0.01) | 0.177 (p < 0.01) |

| Control-surveillance | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.170 (p < 0.01) | 0.200 (p < 0.01) | 0.088 (p < 0.01) | 0.172 (p < 0.01) |

| Psycho-emotional | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.251 (p < 0.01) | 0.289 (p < 0.01) | 0.186 (p < 0.01) | 0.263 (p < 0.01) |

| Physical | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.095 (p < 0.01) | 0.105 (p < 0.01) | 0.083 (p < 0.01) | 0.100 (p < 0.01) |

| Sexual | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.062 (p = 0.04) | 0.123 (p < 0.01) | 0.037 (p = 0.23) | 0.078 (p < 0.01) |

| Total subscale perpetrated | ||||

| Spearman’s Rho (p) | 0.210 (p < 0.01) | 0.267 (p < 0.01) | 0.132 (p < 0.01) | 0.225 (p < 0.01) |

Note: DASS-21: Scale of depression, anxiety and stress-21. Correlation ranges: 0.91 to 1.00: perfect; 0.76 to 0.90: very strong; 0.51 to 0.75: considerable; 0.11 to 0.50: average; 0.01 to 0.10: weak; 0.00: no correlation.

In our sample, psychological violence (cyberbullying, psycho-emotional and control and/or surveillance) was the most prevalent form of violence, followed by sexual and physical violence, at a lower prevalence. All acts of violence showed positive and significant correlations, with depression, anxiety and stress in the medium and/or weak range, with the exception of physical violence perpetrated in relation to stress, which did not show a significant correlation.

When contrasting the DV data on psychological violence perpetrated and experienced, we observed that the percentages of young people in our study who had experienced violence at least 1–2 times was very similar, although this was slightly higher than the data on perpetration, with a difference of .6% for cyberbullying, 0.1% for control and surveillance, and 0.04% for psycho-emotional. This may suggest that both partners were victims and perpetrators in behaviours related to psychological violence. This data was consistent with several studies that highlight the phenomenon of bidirectionality in DV.5,21 However, in the analysis by gender, related to psychological violence, girls scored significantly higher as victims of behaviours related to cyberbullying and control-surveillance, coinciding here in Spain with the data from the latest macro-survey on violence against women (VAW),22 and men showed statistically significant differences as perpetrators of more psycho-emotional violence.

In relation to physical and sexual violence, our findings did not show any bidirectionality for this type of aggression, since the prevalence of DV experienced was four times higher than the results obtained for DV perpetrated, where the results by gender showed that men were the perpetrators, as shown in other studies.5,23 This data confirms the global, regional and national prevalence estimates of physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence against women in 2018, where there was higher prevalence in the younger age cohort.24

With regard to the effect of DV suffered on the mental health of young people, our research has shown positive and significant correlations in all of these, where the greater the DV, the more serious the states of depression, anxiety and stress. In relation to psychological DV, recent research has shown that cyberbullying has been associated mainly with depression23,25,26 and anxiety,26 with a greater effect on girls,20 coinciding with our results. Psycho-emotional and control and/or surveillance violence has also been associated with greater levels of depression8,27and anxiety,27 again coinciding with our findings. Regarding sexual violence, there was a higher correlation on average with anxiety, coinciding with the study by An et al. 2019,28 where those who had suffered sexual violence had a higher risk of experiencing an anxiety disorder over and above any other mental disorder, with girls being the most affected. Finally, physical violence in our study also correlated with depression and anxiety, coinciding with the longitudinal study by Ulloa et al., where physical violence was positively associated with increased symptoms of anxiety and depression throughout the study.29

All these forms of victimisation need to be addressed early, as any form of DV experienced is associated with a significant increase in the likelihood of a lifetime mental disorder.28

On the other hand, our research shows that higher levels of perpetrated DV were associated with worse depression, anxiety and stress. However, little research has been found in the field of education that has analysed the relationship between these variables. Only one study was found, in which men who reported depression were more likely to perpetrate DV (physical, sexual and psychological) towards girls, moreover, having symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder was a predictor of their perpetrating sexual DV.8

It should be noted that, although the correlations obtained were average to weak, they should be paid some attention, since in psychological constructs such as DV and in a non-clinical population, correlations have been established with lower but not negligible thresholds.30

The findings in this study should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. The cross-sectional design did not enable us to control for the time factor and observe its influence on the findings obtained. The sample was by convenience, so this was not representative of the university context, with a much higher percentage of women (85%) compared to men (15%). Thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. In addition, the degree of participation with respect to areas of knowledge was very unequal. Finally, the data collection by means of a self-administered questionnaire may have led to some bias related to systematic responses. It should be noted that these limitations will be considered by the authors of this study and future research will seek to run a prospective study with a representative sample from the university population, or a study in groups where no similar research appears to exist.

In conclusion, we highlight the importance of continuing research in the university context, as these institutions should be guarantors of egalitarian and health-promoting relationships. The data obtained have shown a worrying prevalence of DV that is related to poorer mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety and stress. These results should serve as a starting point to help develop different equality and health promotion plans in Andalusian universities, where nursing could play a relevant role due to its training and awareness of gender violence and health. This could improve the quality of life in the Andalusian university community and be passed on to society at large. In any case, continued research is needed into other variables that may cause interference, as well as running longitudinal studies and looking in more depth into the findings obtained.

FundingThis research was funded by the Andalusian Youth Institutein a contract with private companies (Arts. 68/83 LOU): Promotion of healthy relationships in Andalusian university youth. Prevention of gender violence (3921/1054).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We would like to express our gratitude to the young participants and to the different institutions and teachers at the Andalusian universities who gave us access, as their dedication contributed to our being able to run this study.