To explore the experiences of primary healthcare (PHC) midwives with the implementation of telemedicine in pregnancy and puerperium care during the Covid-19 pandemic.

MethodExploratory qualitative study based on an inductive content analysis of 15 semi-structured interviews with intentionally selected PHC midwives in four Spanish Autonomous Regions, during 2021–22.

ResultsFive categories were identified: (1) changes in the modality of care in pregnancy and puerperium: prioritization of pregnant women, unprotected puerperium, an increase of home visits and decline of parental education groups, (2) implementation of telemedicine in a changing scenario: the positive and negative side of telemedicine (3) reaction of women to telemedicine (4) strategies implemented by midwives for a humanized care, (5) learning for the future.

ConclusionsThe use of telemedicine by primary healthcare midwives enabled the care of pregnant and postpartum women during the pandemic in Spain. The positive aspects of the implementation of this type of care raise possibilities for change towards a hybrid format of healthcare.

Explorar las experiencias de matronas/es de atención primaria de salud (APS) con la implementación de la telemedicina en la atención al embarazo y puerperio durante la pandemia por COVID-19.

MétodoEstudio cualitativo exploratorio basado en análisis de contenido inductivo de 15 entrevistas semiestructuradas realizadas a matronas/es de APS en 2021–2022, seleccionadas intencionalmente en cuatro Comunidades Autónomas españolas.

ResultadosSe identificaron cinco categorías: (1) cambios en la modalidad de atención en el embarazo y puerperio: priorización de mujeres embarazadas, puerperio desprotegido, aumento de visitas domiciliarias y declive de los grupos de educación parental, (2) implementación de la telemedicina en un escenario cambiante: el lado positivo y negativo de la telemedicina (3) reacción de las mujeres ante la telemedicina (4) estrategias implementadas por las matronas para un cuidado humanizado, (5) aprendizajes para el futuro.

ConclusionesEl uso de la telemedicina por parte de matronas de atención primaria posibilitó la atención de mujeres embarazadas y puérperas durante la pandemia en España. Los aspectos positivos de la puesta en marcha de este tipo de atención plantean posibilidades de cambio hacia un formato híbrido de atención sanitaria.

What is known?

Telemedicine aims to provide clinical support via ICT to improve health outcomes. During the pandemic, it increased healthcare coverage.

What it contributes?

The use of telemedicine made it possible to provide care during pregnancy and the postpartum period, and brought advantages which mean that new forms of care and follow-up could be considered that could be applicable to other vulnerable populations or those with special needs.

In March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared coronavirus disease (COVID-19) a global public health emergency. In Spain, a state of alert was decreed, strict lockdown was enforced, and non-essential activities were suspended.1 During the first wave of the pandemic, measures were implemented with regard to pregnancy and the postpartum period such as redistributing staff functions, transforming maternity units into COVID-19 units, excluding partners during delivery, separating mother and baby in the immediate postnatal period, placing restrictions on breastfeeding, cancelling visits, reducing access to prenatal care, shortening postpartum stays, and barring accompanying persons.2–4

The aim of telemedicine is to provide clinical support using information and communication technology (ICT) to improve health outcomes, and is a changing practice dependent on technological advances, needs, and health contexts.5 It was widely used in primary health care (PHC) for preparation for delivery, early antenatal interviews, pregnancy follow-up visits, and postnatal visits, and follow-up.6,7 As a consequence, routine pregnancy checks were reduced, which may have influenced the number of caesarean sections and instrumental deliveries,3,8 as well as attendance at hospital antenatal care, postnatal clinics, and infant immunisation,4 and home visits increased to avoid travel to health centres.9

International studies conclude that implementing telemedicine made it possible to continue providing healthcare during this period, saving time for patients in travelling and waiting in consultation rooms, providing greater time flexibility, and greater coverage in both urban and rural areas.10–13 Even so, drawbacks to implementing telemedicine in the future need to be examined, such as concerns about incomplete assessment and physical examination, more barriers to a relationship of trust with healthcare staff, and a deepening of inequalities resulting from limited access to technological devices and connectivity.12,13

In the Spanish context, the experiences and attitudes of midwives in the care during pregnancy and childbirth of women infected by COVID-19 have been explored14; the perceptions of midwives who were on the front line of care, both in PHC and in specialised care, during the first months of the pandemic15; the role of nurses and midwives in implementing video-consultation,16 and evaluating the effects of other measures implemented in some hospitals, such as early discharge and home visits for postpartum follow-up from the perspective of midwifery residents.9,17 However, what using telemedicine as a unique care tool for the care of pregnant and postpartum women by PHC midwives has entailed has not been specifically addressed.

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of PHC midwives in implementing telemedicine in pregnancy and postpartum care during the pandemic.

MethodStudy designQualitative phenomenological study conducted in four Spanish autonomous communities (AC) between July 2021 and February 2022. This theoretical-methodological perspective was used because it is a strategy that enables us to focus on experiences and interpretations of social phenomena based on people's experiences.18

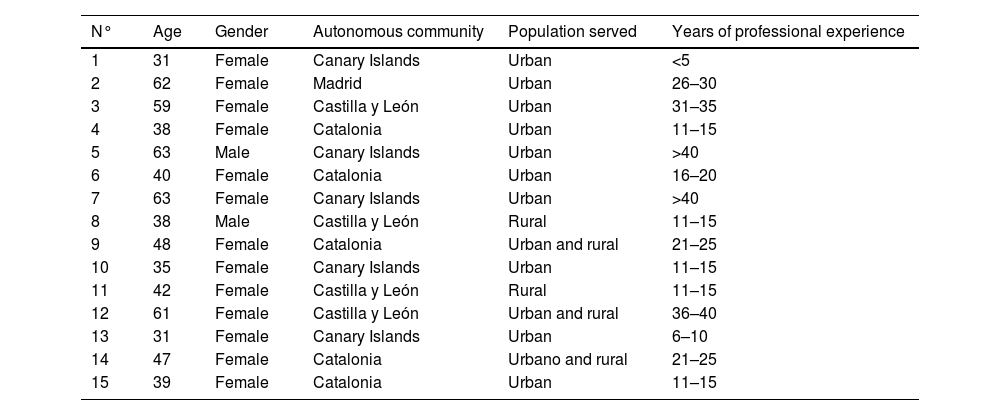

PopulationPurposive sampling from which 15 midwives were recruited (13 women, 2 men) who worked in pregnancy and postpartum care in PHC during the COVID-19 pandemic with a minimum of two years of professional experience in Catalonia, Madrid, Canary Islands, and Castilla y León. The selection was made through contact with key informants in the Health Services, previously identified by one of the researchers. Afterwards, the midwives interviewed facilitated contact with other participants, and thus snowball sampling was also conducted.

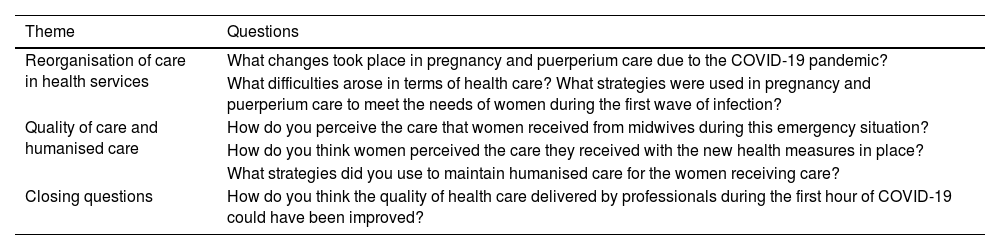

Data collectionSemi-structured interviews using an interview script designed by the investigators, based on the objectives of the study and the literature review (Table 1). One interview per participant was conducted by video call (between 30 and 60 min), which was recorded and transcribed after the informed consent form was signed.

Interview script.

| Theme | Questions |

|---|---|

| Reorganisation of care in health services | What changes took place in pregnancy and puerperium care due to the COVID-19 pandemic? |

| What difficulties arose in terms of health care? What strategies were used in pregnancy and puerperium care to meet the needs of women during the first wave of infection? | |

| Quality of care and humanised care | How do you perceive the care that women received from midwives during this emergency situation? |

| How do you think women perceived the care they received with the new health measures in place? | |

| What strategies did you use to maintain humanised care for the women receiving care? | |

| Closing questions | How do you think the quality of health care delivered by professionals during the first hour of COVID-19 could have been improved? |

The transcripts were analysed following inductive content analysis.19 First, two of the investigators read through the interviews to get an overview of the information collected. They then identified units of meaning which were labelled with emerging codes. Thus, code clusters were formed according to their similarities. After reviewing the code groups and the textual quotations from the interviews, categories and subcategories emerged inductively and were organised into themes. ATLAS.ti 9.3.1 software was used to support the management and coding of the information.

Ethical aspectsThis work was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova en Lleida in 2021 (CEIC-2460). To maintain the confidentiality of the data, participants' data were replaced by a randomly assigned number. All data in the textual quotations that could make the participants identifiable were eliminated. Testimonies were identified by the letter E for "entrevista (interview)" and a number.

ReflexivityThe authors have extensive experience in qualitative health and clinical nursing research. There was no prior relationship between them and the participants. A reflexive process was used in the design, data collection, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. For example, by collecting field notes during and after the interviews and discussing the results with the rest of the team.

ResultsThe characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 2.

Profile of the participants (n = 15).

| N° | Age | Gender | Autonomous community | Population served | Years of professional experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | Female | Canary Islands | Urban | <5 |

| 2 | 62 | Female | Madrid | Urban | 26–30 |

| 3 | 59 | Female | Castilla y León | Urban | 31–35 |

| 4 | 38 | Female | Catalonia | Urban | 11–15 |

| 5 | 63 | Male | Canary Islands | Urban | >40 |

| 6 | 40 | Female | Catalonia | Urban | 16–20 |

| 7 | 63 | Female | Canary Islands | Urban | >40 |

| 8 | 38 | Male | Castilla y León | Rural | 11–15 |

| 9 | 48 | Female | Catalonia | Urban and rural | 21–25 |

| 10 | 35 | Female | Canary Islands | Urban | 11–15 |

| 11 | 42 | Female | Castilla y León | Rural | 11–15 |

| 12 | 61 | Female | Castilla y León | Urban and rural | 36–40 |

| 13 | 31 | Female | Canary Islands | Urban | 6–10 |

| 14 | 47 | Female | Catalonia | Urbano and rural | 21–25 |

| 15 | 39 | Female | Catalonia | Urban | 11–15 |

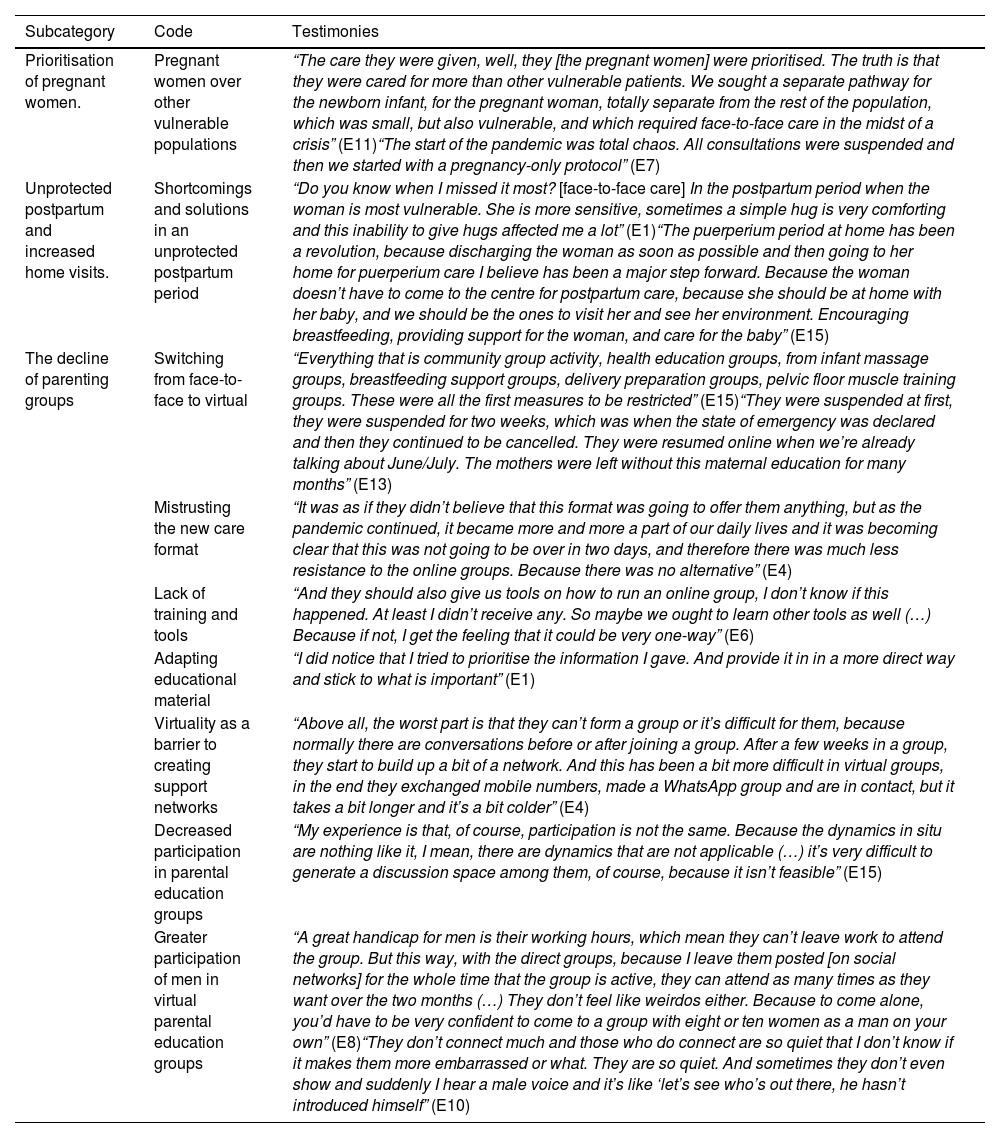

We organised the results into five categories, the first two of which are divided into six sub-categories. Representative testimonies can be found in Tables 3–6.

Subcategories, codes, and testimonies for category 1 "Changes in the modality of pregnancy and postpartum care".

| Subcategory | Code | Testimonies |

|---|---|---|

| Prioritisation of pregnant women. | Pregnant women over other vulnerable populations | “The care they were given, well, they [the pregnant women] were prioritised. The truth is that they were cared for more than other vulnerable patients. We sought a separate pathway for the newborn infant, for the pregnant woman, totally separate from the rest of the population, which was small, but also vulnerable, and which required face-to-face care in the midst of a crisis” (E11)“The start of the pandemic was total chaos. All consultations were suspended and then we started with a pregnancy-only protocol” (E7) |

| Unprotected postpartum and increased home visits. | Shortcomings and solutions in an unprotected postpartum period | “Do you know when I missed it most? [face-to-face care] In the postpartum period when the woman is most vulnerable. She is more sensitive, sometimes a simple hug is very comforting and this inability to give hugs affected me a lot” (E1)“The puerperium period at home has been a revolution, because discharging the woman as soon as possible and then going to her home for puerperium care I believe has been a major step forward. Because the woman doesn’t have to come to the centre for postpartum care, because she should be at home with her baby, and we should be the ones to visit her and see her environment. Encouraging breastfeeding, providing support for the woman, and care for the baby” (E15) |

| The decline of parenting groups | Switching from face-to-face to virtual | “Everything that is community group activity, health education groups, from infant massage groups, breastfeeding support groups, delivery preparation groups, pelvic floor muscle training groups. These were all the first measures to be restricted” (E15)“They were suspended at first, they were suspended for two weeks, which was when the state of emergency was declared and then they continued to be cancelled. They were resumed online when we’re already talking about June/July. The mothers were left without this maternal education for many months” (E13) |

| Mistrusting the new care format | “It was as if they didn’t believe that this format was going to offer them anything, but as the pandemic continued, it became more and more a part of our daily lives and it was becoming clear that this was not going to be over in two days, and therefore there was much less resistance to the online groups. Because there was no alternative” (E4) | |

| Lack of training and tools | “And they should also give us tools on how to run an online group, I don’t know if this happened. At least I didn’t receive any. So maybe we ought to learn other tools as well (…) Because if not, I get the feeling that it could be very one-way” (E6) | |

| Adapting educational material | “I did notice that I tried to prioritise the information I gave. And provide it in in a more direct way and stick to what is important” (E1) | |

| Virtuality as a barrier to creating support networks | “Above all, the worst part is that they can’t form a group or it’s difficult for them, because normally there are conversations before or after joining a group. After a few weeks in a group, they start to build up a bit of a network. And this has been a bit more difficult in virtual groups, in the end they exchanged mobile numbers, made a WhatsApp group and are in contact, but it takes a bit longer and it’s a bit colder” (E4) | |

| Decreased participation in parental education groups | “My experience is that, of course, participation is not the same. Because the dynamics in situ are nothing like it, I mean, there are dynamics that are not applicable (…) it’s very difficult to generate a discussion space among them, of course, because it isn’t feasible” (E15) | |

| Greater participation of men in virtual parental education groups | “A great handicap for men is their working hours, which mean they can’t leave work to attend the group. But this way, with the direct groups, because I leave them posted [on social networks] for the whole time that the group is active, they can attend as many times as they want over the two months (…) They don’t feel like weirdos either. Because to come alone, you’d have to be very confident to come to a group with eight or ten women as a man on your own” (E8)“They don’t connect much and those who do connect are so quiet that I don’t know if it makes them more embarrassed or what. They are so quiet. And sometimes they don’t even show and suddenly I hear a male voice and it’s like ‘let’s see who’s out there, he hasn’t introduced himself” (E10) |

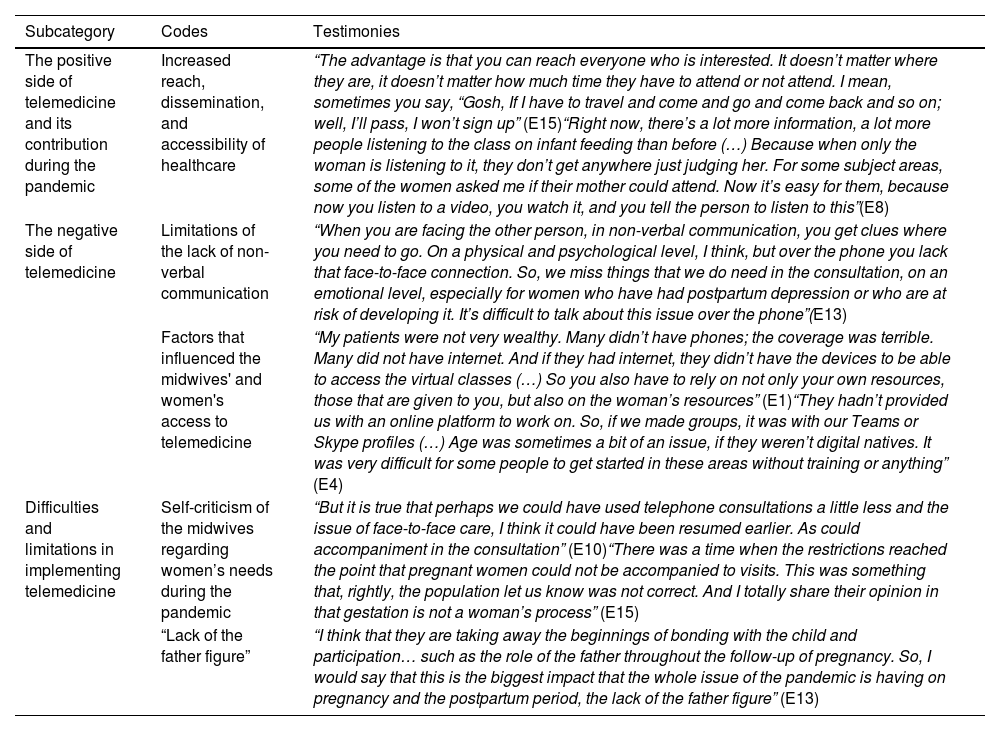

Subcategory, codes, and testimonies for category 2 “Implementation of telemedicine in a changing scenario”.

| Subcategory | Codes | Testimonies |

|---|---|---|

| The positive side of telemedicine and its contribution during the pandemic | Increased reach, dissemination, and accessibility of healthcare | “The advantage is that you can reach everyone who is interested. It doesn’t matter where they are, it doesn’t matter how much time they have to attend or not attend. I mean, sometimes you say, “Gosh, If I have to travel and come and go and come back and so on; well, I’ll pass, I won’t sign up” (E15)“Right now, there’s a lot more information, a lot more people listening to the class on infant feeding than before (…) Because when only the woman is listening to it, they don’t get anywhere just judging her. For some subject areas, some of the women asked me if their mother could attend. Now it’s easy for them, because now you listen to a video, you watch it, and you tell the person to listen to this”(E8) |

| The negative side of telemedicine | Limitations of the lack of non-verbal communication | “When you are facing the other person, in non-verbal communication, you get clues where you need to go. On a physical and psychological level, I think, but over the phone you lack that face-to-face connection. So, we miss things that we do need in the consultation, on an emotional level, especially for women who have had postpartum depression or who are at risk of developing it. It’s difficult to talk about this issue over the phone”(E13) |

| Factors that influenced the midwives' and women's access to telemedicine | “My patients were not very wealthy. Many didn’t have phones; the coverage was terrible. Many did not have internet. And if they had internet, they didn’t have the devices to be able to access the virtual classes (…) So you also have to rely on not only your own resources, those that are given to you, but also on the woman’s resources” (E1)“They hadn’t provided us with an online platform to work on. So, if we made groups, it was with our Teams or Skype profiles (…) Age was sometimes a bit of an issue, if they weren’t digital natives. It was very difficult for some people to get started in these areas without training or anything” (E4) | |

| Difficulties and limitations in implementing telemedicine | Self-criticism of the midwives regarding women’s needs during the pandemic | “But it is true that perhaps we could have used telephone consultations a little less and the issue of face-to-face care, I think it could have been resumed earlier. As could accompaniment in the consultation” (E10)“There was a time when the restrictions reached the point that pregnant women could not be accompanied to visits. This was something that, rightly, the population let us know was not correct. And I totally share their opinion in that gestation is not a woman’s process” (E15) |

| “Lack of the father figure” | “I think that they are taking away the beginnings of bonding with the child and participation… such as the role of the father throughout the follow-up of pregnancy. So, I would say that this is the biggest impact that the whole issue of the pandemic is having on pregnancy and the postpartum period, the lack of the father figure” (E13) |

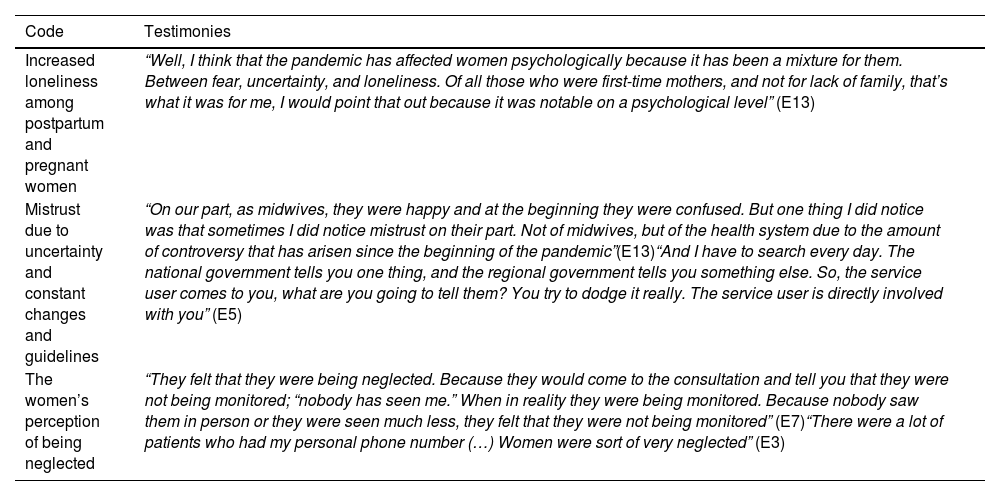

Codes and testimonies for category 3 “Reaction of women to telemedicine”.

| Code | Testimonies |

|---|---|

| Increased loneliness among postpartum and pregnant women | “Well, I think that the pandemic has affected women psychologically because it has been a mixture for them. Between fear, uncertainty, and loneliness. Of all those who were first-time mothers, and not for lack of family, that’s what it was for me, I would point that out because it was notable on a psychological level” (E13) |

| Mistrust due to uncertainty and constant changes and guidelines | “On our part, as midwives, they were happy and at the beginning they were confused. But one thing I did notice was that sometimes I did notice mistrust on their part. Not of midwives, but of the health system due to the amount of controversy that has arisen since the beginning of the pandemic”(E13)“And I have to search every day. The national government tells you one thing, and the regional government tells you something else. So, the service user comes to you, what are you going to tell them? You try to dodge it really. The service user is directly involved with you” (E5) |

| The women’s perception of being neglected | “They felt that they were being neglected. Because they would come to the consultation and tell you that they were not being monitored; “nobody has seen me.” When in reality they were being monitored. Because nobody saw them in person or they were seen much less, they felt that they were not being monitored” (E7)“There were a lot of patients who had my personal phone number (…) Women were sort of very neglected” (E3) |

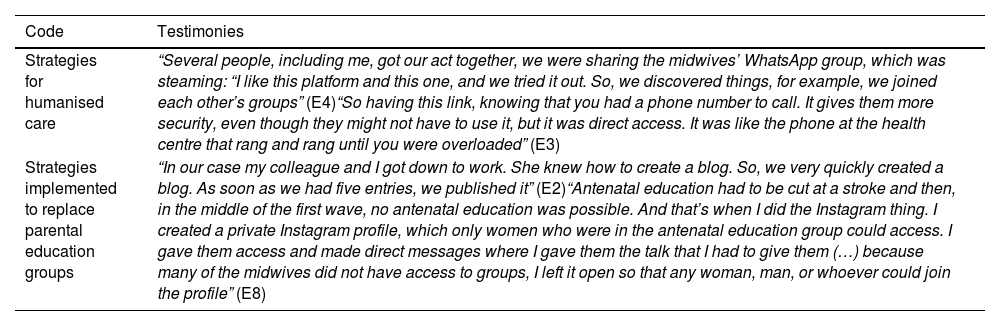

Codes and testimonies for category 4 “Strategies implemented by midwives for humanised care”.

| Code | Testimonies |

|---|---|

| Strategies for humanised care | “Several people, including me, got our act together, we were sharing the midwives’ WhatsApp group, which was steaming: “I like this platform and this one, and we tried it out. So, we discovered things, for example, we joined each other’s groups” (E4)“So having this link, knowing that you had a phone number to call. It gives them more security, even though they might not have to use it, but it was direct access. It was like the phone at the health centre that rang and rang until you were overloaded” (E3) |

| Strategies implemented to replace parental education groups | “In our case my colleague and I got down to work. She knew how to create a blog. So, we very quickly created a blog. As soon as we had five entries, we published it” (E2)“Antenatal education had to be cut at a stroke and then, in the middle of the first wave, no antenatal education was possible. And that’s when I did the Instagram thing. I created a private Instagram profile, which only women who were in the antenatal education group could access. I gave them access and made direct messages where I gave them the talk that I had to give them (…) because many of the midwives did not have access to groups, I left it open so that any woman, man, or whoever could join the profile” (E8) |

In response to the health crisis of the first wave, all face-to-face visits were cancelled to avoid the risk of contagion as much as possible. Subsequently, and in accordance with protocols, an order of prioritisation was established for the care of women, giving special emphasis to pregnant women, and leaving aside other practices such as screening, for example.

Unprotected postpartum and increased home visitsPostpartum visits were switched to telephone or video-call visits during the first wave of the pandemic. In pregnancy, visits were maintained for longer periods of time on a non-face-to-face basis, except for specific cases requiring immediate attention. The midwives agreed that women's health in the postpartum period was unprotected for this reason.

The decline of parental education groupsThe midwives explained that the groups were cancelled once the pandemic was declared. While in some Spanish regions they were not restarted until late in the pandemic, in others they were implemented virtually, which was one of the most long-lasting changes. The midwives stated that they perceived that women were resistant to this change from groups to a virtual modality because they did not trust and did not know how to use the platforms.

Implementing telemedicine was a challenge for the midwives, as they had received no training to adapt to this new modality. The main changes made were a reduction in delivery of content and information, and support with visual and auditory stimuli in the presentations. The main limitation identified with the change of modality in the parental education groups was that support networks with other mothers, which had constituted one of their major benefits, were impeded. Interaction was not the same through online contact, despite the efforts of the midwives.

According to the testimonies both attendance and participation in these groups was clearly affected by the change of modality. Some midwives explained this as resulting from the loss of group facilitation activities combined with the women's mistrust, which led to a loss of interest in these activities. However, the midwives agreed that it made it easier for parents to participate because they were able to better coordinate attendance with work schedules and/or look at the content at a later time.

This, according to the midwives, had to do not only with compatibility of schedules but also with the convenience of not having to face a group of women, in many cases alone. Virtuality allowed them to participate with less pressure and more ease, without feeling like "weirdos"º or standing out too much.

Implementation of telemedicine in a changing scenario (Table 4)The positive side of telemedicine and its contribution during the pandemicAccording to the midwives, the implementation of telemedicine made it possible to maintain care for women, which would otherwise have been cancelled due to the restrictive measures during the pandemic. The main advantages reported were saving time for telephone consultations, which allowed time to be spent on visits that required it, and greater accessibility to migrant and rural populations and to those for whom being face-to-face impeded visiting the health centre. The use of new technologies allowed greater accessibility, dissemination, and reach of information, encouraging the involvement of other family members.

The negative side of telemedicineThe loss of closeness to women and warmth in health care was one of the main difficulties reported by the midwives. They felt that valuable information was lost in the assessment of the women, mainly because of the role played by paraverbal language and the bond of trust with the women.

Also, access to technological devices or stable internet connection was identified as a limitation for the women. This digital divide also extended to the midwives, as the lack of technological resources in health centres delayed implementing virtual visits to train midwives in the use of these new technological tools. This meant they had to teach themselves how to use them, especially those who were not digital natives.

Difficulties and limitations in implementing telemedicineThe midwives were self-critical of their work and reported limitations in the care of women. For example, the prioritisation of prevention of COVID-19 infection over other needs of pregnant and postpartum women; delay in restarting face-to-face visits and parenting education groups, in many cases related to the convenience of the professionals; restriction of parents from attending extended visits, despite the importance for the wellbeing of the women and children. One of the midwives commented that the exclusion of men directly affected their involvement and bonding with their newborn infants.

Reaction of women to telemedicine (Table 5)The midwives perceived that, although the women adapted to the care they received, and adopted compassionate attitudes towards the professionals because of the pandemic context, the lack of face-to-face care made them feel neglected. They also perceived that there was an increase in loneliness among both pregnant and postpartum women, which added to the anguish and fear brought about by the uncertainty of the pandemic. This added to the mistrust that the women felt, according to the midwives, towards the health system because of the fluctuating guidelines that were issued to the whole population. This was also experienced by the midwives, with the constant changes in protocols and differences in the application of measures in each Autonomous Community, which generated uncertainty and insecurity.

Strategies implemented by midwives for humanised care (Table 6)The strategies used by the respondents to provide humanised care in this new context were facilitating direct contact or even their own personal telephone number in order to be more accessible to the women and provide them with peace of mind, answering queries and following up by e-mail, prioritising video-call visits over telephone visits to transmit greater closeness, and collaborating with other midwives to resolve concerns and challenges with telemedicine, by means of WhatsApp® groups.

Strategies were deployed in an attempt to replace the cancelled parental education groups. Some of the measures included referring women to websites with reliable information that they had checked, creating blogs where midwives wrote posts with information, creating profiles on social networks both as a platform for holding online parental education groups and as a means of disseminating information, taking advantage of the resources of other colleagues, and referring women to these spaces.

Learning for the futureTo improve care and accessibility to health services in times of pandemic, they suggested the need for more material and human resources, such as more answering machines or staff to take all calls from users, increased time for visits, provision of material resources such as means of transport or appropriate digital platforms and human resources to provide visits pending since the COVID pandemic.

DiscussionThis study shows that midwives identified positive and negative aspects of the implementation of telemedicine, and had to deploy strategies to promote humanised care and to supplement face-to-face parental education.

Telemedicine in PHC during the COVID-19 pandemic was implemented in both European and Latin American countries,20,21 although it was not always successful. As evidenced by the results of this study, it was implemented as the epidemiological situation fluctuated, which affected decision-making on the part of professionals as to which protocol to follow at any given time.11,20 Internationally22–24 it has also been highlighted that this type of practice led to great heterogeneity in the health response. According to other studies,25,26 in some cases it was even incompatible with good practice. Health professionals expressed concern about the long-term effects of these measures.11 For example, with regard to the consequences of fathers being limited in their assuming parental responsibility.27

Like the professionals in this study, the lack of a close relationship with the women was identified as one of the main disadvantages of telemedicine.12,23 Other studies also conclude that telemedicine affects the bond of trust with the midwife through less connection, misinterpreting information provided, and less mutual understanding.10,11 A factor detrimental to the formation of this bond was the lack of non-verbal communication. Non-verbal communication fosters trust in the relationship with midwives and assessment of the women's needs.22

The lack of training in telemedicine for midwives and the digital divide, more pronounced in older midwives, were other limitations reported in this study. A recent study also relates the level of digital competence to age.28 As in this study, midwives had to teach themselves how to provide telematic care.21 In some contexts, they used social networks for health education.23 In this regard, it is important to bear in mind that social networking groups moderated and supervised by midwives enhance health education.29,30

Access to technological devices and stable connection networks, lack of digital literacy, and language barriers were limitations for women in telemedicine, according to the midwives interviewed in our study. These issues are often exacerbated in rural or low-income settings.10,24 However, a reported concern was the lack of privacy resulting from telemedicine consultations, especially for sensitive topics, which is confirmed by a UK study, where women reported feeling self-conscious about discussing sensitive topics such as mental health31 or gender-based violence.10,32

Several studies24,32 agree on the advantages of telemedicine reported in this study, such as savings in and optimisation of consultation time, greater accessibility, and improvements in the dissemination and scope of information. These advantages open up the possibility of using telemedicine beyond the pandemic according to the midwives in this study, enabling a flexible format of care between face-to-face and virtual. However, technological access would need to be guaranteed for this, and professionals and service users would need to feel confident in the use of these tools.11,24

The present study has limitations and strengths. The fieldwork was conducted after the first wave of the pandemic in Spain, and therefore the midwives' perceptions are retrospective in aspects related to the lockdown. There were also variations in the incidence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the guidelines between the different ACs, and therefore it should be borne in mind that the sample of this study is limited to midwives from four Spanish ACs. The criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba33 were followed to ensure the validity and quality of this qualitative research, based on credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

As future lines of research, we suggest evaluating the effectiveness and quality of protocolised interventions of hybrid care during pregnancy and puerperium in order to identify which are the most effective for future implementation. We also suggest that the experiences of pregnant and postpartum women receiving this hybrid care be studied in greater depth.

We can conclude that the use of telemedicine has facilitated the care of women during pregnancy and puerperium, and that there are various clear advantages that deserve consideration in moving towards a hybrid format of PHC. This opens up the possibility of new forms of healthcare and follow-up that may be suitable for populations with special needs. In this sense, it is essential that midwives are considered in the formulation of strategies for the use of telemedicine in a hybrid format and training needs. We suggest that training programmes in digital competencies be implemented for professionals as well as the general population.

FundingFunding for pre-doctoral researchers in training at the University of Lleida, Jade Plus.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the respondents for their time and willingness to participate in this study and share their experiences.