To understand the experiences of adults over 65 years of age with type 2 diabetes mellitus, regarding foot self-care.

MethodQualitative phenomenological study with a descriptive approach. It is carried out in the facilities of the Primary Care Center of Les Planes de Sant Joan Despí, Barcelona, belonging to the Catalan Institute of Health. For the data collection, a semi-structured and individual interview was used, with a script of basic aspects to be explored, not closed and focused on the objectives of the research. The interviews were carried out between June 2019 and December 2020. A thematic analysis was carried out concomitantly with the collection of these.

ResultsA final sample of 13 persons (4 men and 9 women) participated in the study. Adherence to diabetic foot self-care recommendations is irregular. Participants explain risky behaviours despite knowing that they can cause injury to feet previously considered high risk. The evaluation of the podiatrist supposes an economic cost that some people cannot afford.

ConclusionsThe nurse has to do an exhaustive follow-up of how persons with diabetes take care of her feet, insisting on preventive recommendations not only in the annual review but every time the person attends the diabetes follow-up consultation. Effective nurse-podiatrist communication is needed to improve prevention and follow-up of people at risk of diabetic foot disease.

Entender las vivencias de los adultos mayores de 65 años con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 respecto al autocuidado de los pies.

MétodoEstudio cualitativo fenomenológico de enfoque descriptivo. Se lleva a término en las dependencias del Centro de Atención Primaria de Les Planes de Sant Joan Despí, Barcelona, perteneciente al Instituto Catalán de la Salud. Para la recogida de datos se utilizó una entrevista semiestructurada e individual, con un guion de aspectos básicos a explorar, no cerrado y centrado en los objetivos de la investigación. Las entrevistas se llevaron a cabo entre junio del 2019 y diciembre del 2020. Se realizó un análisis temático siendo concomitante a la recogida de estos.

ResultadosUna muestra final de 13 personas (4 hombres y 9 mujeres) participaron en el estudio. La adherencia a las recomendaciones del autocuidado del pie diabético es irregular. Los participantes explican conductas de riesgo a pesar de saber que pueden suponer una lesión para unos pies considerados previamente de alto riesgo. La valoración del podólogo supone un coste económico que no pueden permitirse algunas personas.

ConclusionesLa enfermera ha de hacer un seguimiento exhaustivo de cómo las personas con diabetes cuidan sus pies, insistiendo en las recomendaciones preventivas no sólo en la revisión anual, sino cada vez que la persona acude a la consulta de seguimiento de la diabetes. Es necesaria una comunicación efectiva enfermera-podólogo para mejorar la prevención y el seguimiento de las personas con riesgo de sufrir pie diabético.

Proper foot care in older adults diagnosed with diabetes mellitus 2 older adults diagnosed with diabetes mellitus 2 can delay the onset of conditions that lead to ulcers and amputations ulcers and amputations, the latter leading to disability and in many cases to and, in many cases, disability.

What is contributesKnowing the perception that these people have of specific foot care can allow for changes in incorrect habits and promote the cooperation of patients patients in relation to treatment and subsequently to self-care.

The reality of diabetes management means that third party support is required.1 Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) is a chronic disease in which the time elapsed since diagnosis can be linked to the development of chronic complications, including diabetic neuropathy (DN), which is present in 8–12% of these individuals at the time of diagnosis, a percentage that increases to 50–60% of cases 20–25 years following diagnosis.2 Chronic complications appear later in the course of the disease, making it difficult to recognise the severity of symptoms in people with diabetes and, as a result, to implement lifestyle modifications.3 This lack of protective sensitivity prevents the person with diabetes from identifying the onset of ND early, which, coupled with reduced blood flow, increases the risk of the formation of sores, developing infection, and, ultimately, partial or total amputation of the lower extremities (LE).2,3

Complications related to the diabetic foot entail great economic costs, consuming approximately 20% of the resources devoted to the care of people with diabetes. It should be remembered that 50–70% of non-traumatic amputations occur in people with diabetes. Interventions aimed at prevention, such as comprehensive management, education of people with diabetes and their families, as well as interventions by healthcare professionals, have been shown to reduce lower limb amputations by 50–85%.4

Although compliance with treatment involves many aspects such as cooperation, collaboration, therapeutic alliance, monitoring, obedience, observance, adherence, and conformity. The term adherence to treatment is the most widely accepted and appropriate term because of its psychological meaning. Adherence to treatment is a complex behaviour that encompasses behavioural, relational, and volitional aspects that lead the patient to participate in and understand their treatment and compliance with it, so that, together with the health professional, both seek and find the means to achieve the expected results.5 Thus, it can be said that good adherence promotes self-care.

The knowledge and practice of proper foot care by the person with diabetes or their relatives is one of the factors that affect the quality of care6 and can delay the onset of changes that lead to ulcers and amputations, make it possible to change improper habits, and promote patient cooperation in relation to treatment and, subsequently, self-care. Involving families in the care of the disease increases healthy behaviours, adherence to treatment, and correct nutrition and diet; therefore, family support can be thought of as encouraging the person with DM2 to commit to their treatment.7 One of the nursing competencies in this regard is to educate and foster proactive attitudes with respect to the disease. This is particularly important for people with diabetes in terms of lower limb care and preventing complications.8

Hygiene care and the detection of lesions (or signs preceding them) in an insensitive foot depend on the individual’s ability to examine themself. One important factor in the approach to care is the physical difficulty these patients may have in reaching their feet, or simply the confidence that someone else is more adept at hygiene and cleaning tasks, thereby justifying dependence on others. Retinopathy and visual impairment associated with joint limitations make it difficult to inspect and perform such care.2 Thus, the triad of knowledge, attitudes, and practices must be interconnected for effective preventive foot care.8 There is a correlation between the perception of illness and health outcomes because self-management is complex and involves complicated decision-making that depends on people’s perception of their illness in certain terms. It can therefore be argued that poor adherence to treatment can be changed by building up the perception of “living an orderly life.”9 Another defining aspect of foot care is financial problems, assuming that reimbursement for foot care depends on the purchasing power of the person who hires it.10

The person must be the agent of their own disease process; they need to recognise themself as a person with diabetes if they are to be able to promote their own self-care. Self-care behaviours are affected by several factors such as socio-economic, educational, and cultural status. It is important to consider psychological factors, such as emotional distress and depression, more prevalent in these individuals than in the general population,11 which could lead to deficit self-care and, consequently, a high risk of foot injuries.

Bearing in mind the importance of understanding this disease from the perspective of the people who suffer from it, the following question has been posed: What are the experiences of people over 65 years of age with DM2 with regard to foot care and compliance with treatment?

Accordingly, the overall aim of this study was to identify the experiences of people over 65 years of age with DM2 with regard to self-care of their feet. The specific objectives were to discover how these people carry out foot hygiene, pointing out the difficulties they have experienced in foot self-care, as well as to explore the importance they attach to foot care and to find out what information they have received concerning foot self-care.

MethodResearch team and reflectionThe research team consisted of four nurses, two of whom work at the Les Planes Primary Care Centre (CAP), one of them being an associate lecturer at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), in the Department of Nursing; the other two are full-time lecturers of the Nursing Degree Programme at the same university. Three of the researchers are trained in qualitative methodology and hold a PhD degree, while the fourth researcher is a graduate in nursing and this is her first experience using this methodology.

All the researchers are interested in diabetes nursing care and concerned about the causes of non-compliance with prescriptions.

Study designQualitative phenomenological study with a descriptive approach. The aim is to understand how self-care is carried out in people with diabetes and the meaning they attribute to such care. This approach enables us to examine the phenomenon in the natural context in which it takes place and to grasp the social reality by sharing and interpreting the meanings of the individuals involved in it.12

ScopeSant Joan Despí is a municipality with a surface area of 617 km2 and a population of 34,267 inhabitants (data from 2021). The population density is 5,553.8 inhab./km2 (2020 data).

The average age of the population of Sant Joan Despí is 42.5 years, with 17.83% of the population aged 65 years and older (data from 2021). The disposable household income per inhabitant is Є17,806. These statistics are available on the Sant Joan Despí Town Council website and in the HERMES programme of the Diputació de Barcelona.

The study was carried out at the Les Planes Primary Care Centre (CAP Les Planes), in the municipality of Sant Joan Despí (Barcelona). This centre serves the population of the Les Planes district and the Sant Joan residential neighbourhood. It currently provides care to an adult population of 11,962 patients, 982 of whom are diagnosed with DM2, 212 of whom are insulin-dependent and 636 non-insulin-dependent (use of data from the Khalix_2021.ICS. programme).

ParticipantsThe study population comprised all individuals with diabetes treated at the CAP Les Planes, who met the following inclusion criteria: over 65 years of age, diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, who understood Spanish and Catalan, and who did not have any ulcers or amputations in the lower limbs. Likewise, people were excluded if, despite meeting the aforementioned criteria, they suffered from sensory impairment, psychological and/or cognitive deficits, or if they had suffered a stroke.

An opinion-based, non-probabilistic, intentional, and reasoned sampling was carried out. The sampling units were chosen for their ease of accessibility, being people who attended their diabetes check-ups at the nurses’ offices during the data collection period (2019–2020). We looked for those people who could best answer the research questions owing to their experience with the disease (evolution of approximately 10 years) and who were able to understand the phenomenon under study. Gender parity and age variability were pursued. It was considered to be cumulative and sequential, as well as flexible, circular, and reflexive. Sampling was completed at data saturation.

The selection of participants was made by a nurse from the CAP Les Planes healthcare centre, who normally works in the outpatient clinic for chronic patients and who was presented with the characteristics that the participants should have. This nurse did not participate in any other part of this study. All the people who were offered the opportunity to participate in the study accepted.

VariablesSocio-demographic variables such as gender, age, level of education, marital status, who the participants currently live with, and number of children were recorded.

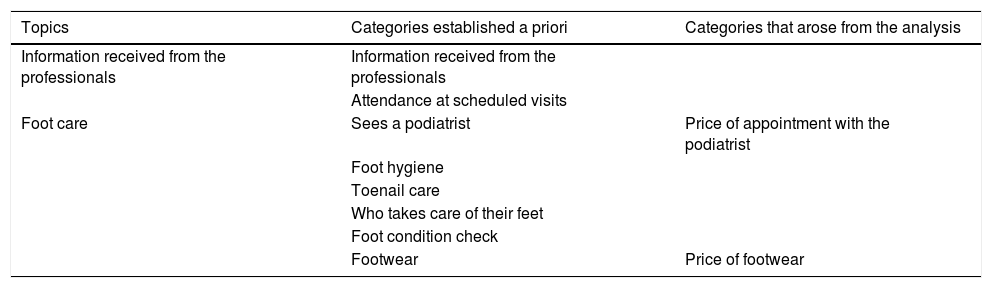

Categories consideredInformation regarding the categories initially envisaged was collected by means of an interview: information provided by the nurse, attendance at scheduled check-ups, foot washing, nail clipping, type of footwear worn, and seeing a podiatrist. During the interviews, two categories concerning foot care emerged in terms of the person’s purchasing power (the price of podiatrist’s care and the price of shoes).

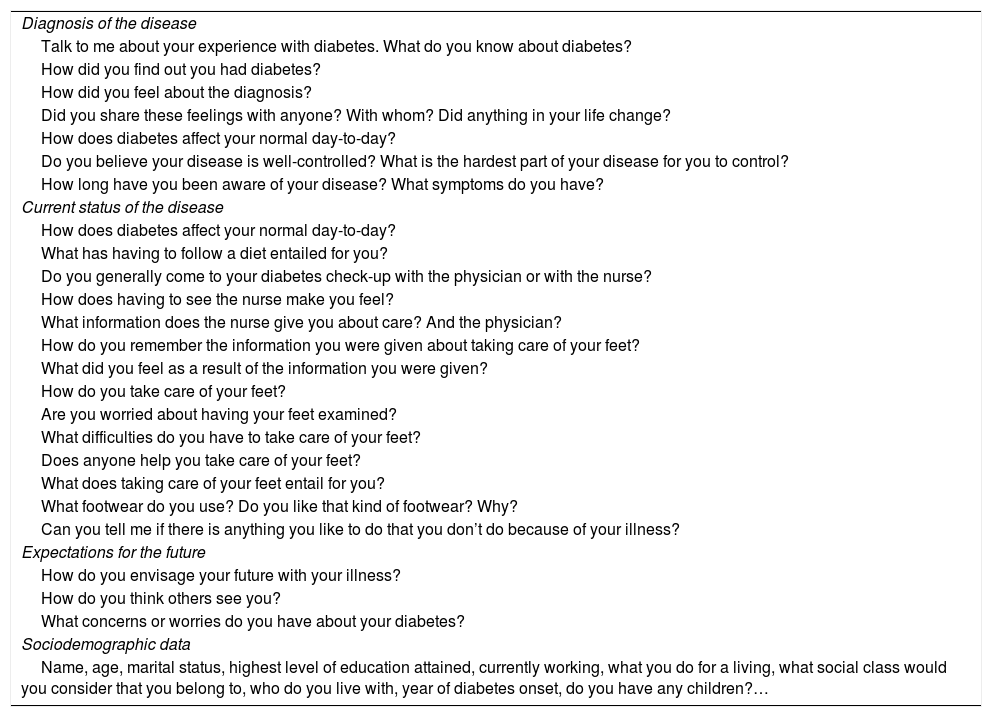

Data collectionData were collected by two nurses from the Les Planes CAP who collected data from informants who were not assigned to their care. A semi-structured, individual interview was conducted, with a script of basic aspects to be explored (Table 1), which was not closed and focused on the objectives of this research. A pilot interview was previously conducted with a person with diabetes, the results of which have not been included in this study. The interview script was modified as the interviews were conducted and data analysis was carried out, which guided the content of the subsequent interviews.

Script to interview patients over 65 years of age with diabetes about foot care.

| Diagnosis of the disease |

| Talk to me about your experience with diabetes. What do you know about diabetes? |

| How did you find out you had diabetes? |

| How did you feel about the diagnosis? |

| Did you share these feelings with anyone? With whom? Did anything in your life change? |

| How does diabetes affect your normal day-to-day? |

| Do you believe your disease is well-controlled? What is the hardest part of your disease for you to control? |

| How long have you been aware of your disease? What symptoms do you have? |

| Current status of the disease |

| How does diabetes affect your normal day-to-day? |

| What has having to follow a diet entailed for you? |

| Do you generally come to your diabetes check-up with the physician or with the nurse? |

| How does having to see the nurse make you feel? |

| What information does the nurse give you about care? And the physician? |

| How do you remember the information you were given about taking care of your feet? |

| What did you feel as a result of the information you were given? |

| How do you take care of your feet? |

| Are you worried about having your feet examined? |

| What difficulties do you have to take care of your feet? |

| Does anyone help you take care of your feet? |

| What does taking care of your feet entail for you? |

| What footwear do you use? Do you like that kind of footwear? Why? |

| Can you tell me if there is anything you like to do that you don’t do because of your illness? |

| Expectations for the future |

| How do you envisage your future with your illness? |

| How do you think others see you? |

| What concerns or worries do you have about your diabetes? |

| Sociodemographic data |

| Name, age, marital status, highest level of education attained, currently working, what you do for a living, what social class would you consider that you belong to, who do you live with, year of diabetes onset, do you have any children?… |

The interviews were carried out between June 2019 and December 2020. They were held in a place previously agreed upon by the participant and the interviewer, in an office that allowed for privacy, with good lighting conditions, and the absence of noise and interruptions. For this purpose, the nursing office of the chronic care clinic was available and all the interviews of the selected participants were performed there. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The duration of the interviews was approximately 30−45 min. Questions were asked about diagnosis of the disease, podiatric care, and socio-demographic data. An attempt was made to use a questionnaire with open-ended questions to facilitate the participants’ expressing their experiences, pointing out the information linked to the experience of care and self-care of the feet, and the information obtained from the health professionals in this regard.

The researcher had a notebook in which they wrote down their observations and impressions during the interview while at the same time recording the audio of the interview.

Data analysisA thematic analysis was carried out concurrently with the collection of the data. Following the literal transcription of each interview, it was returned to the participant to be read, with the aim of confirming or rectifying anything that did not reflect the participant’s experiences and in this way, triangulating the participant/ researcher. After receiving the primary documents, they were protected, eliminating anything that could identify the participants and the people who appeared in the conversation, assigning them fictitious names and maintaining their gender.

Researcher triangulation was undertaken; two researchers analysed the data separately and then pooled their findings.

The following process of analysis was applied: first, the texts were read repeatedly to familiarise the researcher with the discourse, elaborating pre-analytical intuitions and coding the findings that appeared in the interviews, which were then pooled into categories. Once this process was completed, an explanatory framework was constructed and the findings of the analysis were checked against the original data.

During the analysis, two main themes were identified: information received from professionals and foot care. Categories were established which we have called "a priori" because they were explored in order to meet the objectives of the study. During the interview, we looked more deeply into foot hygiene and care, who carries this out, how and when this care is performed, etc. Emerging categories arose as a finding during the interview.

The Atlas Ti 6.2® qualitative analysis software was used to assist the analysis.

RigourThe criteria for rigour used in this research are those referenced by Guba.13 During the study, methods were used to ensure the strength of the data. Data credibility is achieved by making the mode of data collection explicit, triangulating the data by another researcher, and obtaining feedback from informants. At the same time, the data are presented with the support of examples (verbatims). Transferability is achieved by the heterogeneity of the sample; interviews were conducted with men and women of different ages, respecting the inclusion criteria stipulated, and describing the sample. Consistency is underpinned by the comprehensive description of the data collection technique, the semi-structured interview. Finally, confirmability is accomplished with the verbatim transcriptions and direct quotations from the audio recordings and field notes of the researcher conducting the interview.

Ethical considerationsIn this study, all the necessary ethical considerations were carried out to safeguard the confidentiality, safety, and well-being of the subjects who participated. To this end, the evaluation of the Idiap Jordi Gol Research Ethics Committee was requested at the meeting held on 25 August 2018, which considered that it complied with the ethical requirements of confidentiality and good clinical practice currently in force and assigned code P18/106 to the project. The principal and collaborating investigators introduced themselves to the participants, explained the research objectives, the study process, and the study interviews. Signed informed consent forms were collected, maintaining the anonymity of the study participants by assigning a fictitious name to each. Participants were also informed that they were free to withdraw at any stage of the project without consequence, respecting the bioethical principles of the Helsinki declaration. The interviews and transcripts were kept under code and consulted exclusively by the researchers. The destruction of all data is planned for three years after the completion of the study.

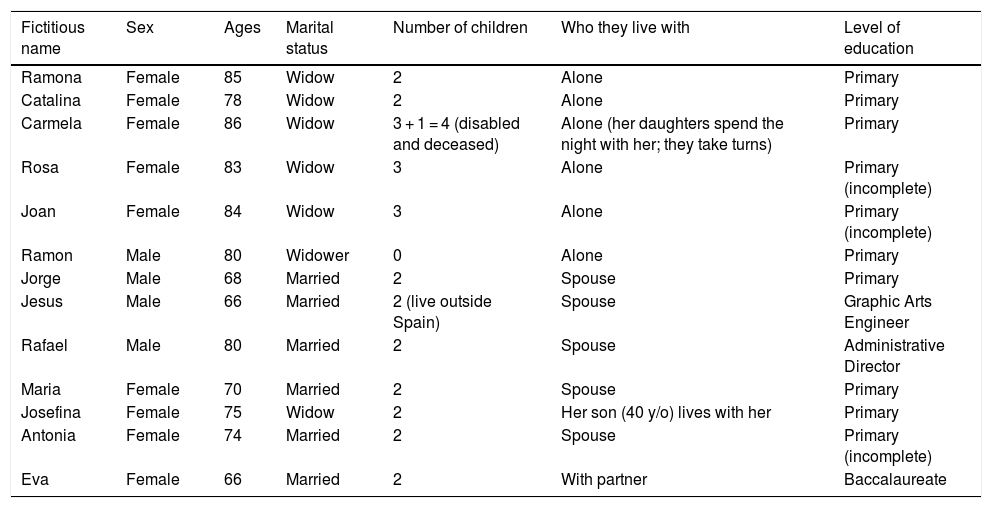

ResultsThe final sample consisted of 13 participants. Thirteen interviews were conducted, nine of which were with women and four with men. The average age was 76.54 years, with a minimum age of 66 and a maximum of 86. As for subjects’ level of education, three had higher education (23.1%), two had not finished basic education (15.4%), and seven people had primary or complete education (53.8%). Most of them reported living at home with their partners (46.1%), alone (38.5%), or with their children (15.4%). The profiles of the respondents can be found in Table 2.

Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and profile.

| Fictitious name | Sex | Ages | Marital status | Number of children | Who they live with | Level of education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramona | Female | 85 | Widow | 2 | Alone | Primary |

| Catalina | Female | 78 | Widow | 2 | Alone | Primary |

| Carmela | Female | 86 | Widow | 3 + 1 = 4 (disabled and deceased) | Alone (her daughters spend the night with her; they take turns) | Primary |

| Rosa | Female | 83 | Widow | 3 | Alone | Primary (incomplete) |

| Joan | Female | 84 | Widow | 3 | Alone | Primary (incomplete) |

| Ramon | Male | 80 | Widower | 0 | Alone | Primary |

| Jorge | Male | 68 | Married | 2 | Spouse | Primary |

| Jesus | Male | 66 | Married | 2 (live outside Spain) | Spouse | Graphic Arts Engineer |

| Rafael | Male | 80 | Married | 2 | Spouse | Administrative Director |

| Maria | Female | 70 | Married | 2 | Spouse | Primary |

| Josefina | Female | 75 | Widow | 2 | Her son (40 y/o) lives with her | Primary |

| Antonia | Female | 74 | Married | 2 | Spouse | Primary (incomplete) |

| Eva | Female | 66 | Married | 2 | With partner | Baccalaureate |

Following data analysis, the categories were grouped into two broad themes reflecting participants’ perceptions of foot care: previous information received from health professionals and foot care (how to do it). Under foot care, categories such as attending scheduled visits, seeing a podiatrist, foot hygiene, nail care, who performs foot care, and checking the condition of the feet were noted (Table 3). Two emerging categories related to foot care according to the person’s purchasing power arose; the cost of podiatrist’s care and the price of footwear used.

Topics and categories considered.

| Topics | Categories established a priori | Categories that arose from the analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Information received from the professionals | Information received from the professionals | |

| Attendance at scheduled visits | ||

| Foot care | Sees a podiatrist | Price of appointment with the podiatrist |

| Foot hygiene | ||

| Toenail care | ||

| Who takes care of their feet | ||

| Foot condition check | ||

| Footwear | Price of footwear |

When talking about foot care in general, patients receive information from the nurse about comprehensive foot care at each check-up visit. Appointments with the nurse should be scheduled for every six months and each visit should include an examination of the condition of the patient’s feet. Patients are generally informed about risk behaviours and their feet are visually inspected and a neurological examination of their protective sensitivity conducted. Generally speaking, this examination is performed at least once a year during an appointment. In cases in which the patient indicates that some kind of problem has been detected, a prompt appointment to examine and inspect [the person’s feet] is made.

On the whole, the participants indicated that they received very little information from the nurse. In this sense, despite the fact that all the respondents said that they attended regular check-ups and visits to the podiatrist, some participants stated that they had received little information from the professionals regarding the health problem and the self-care measures to be implemented; in this regard, Rafael, 80 years old, said that he had received very little information from the podiatrist, and that he had received very little information from the professionals concerning the health problem and the self-care measures to be taken: “I was given very little information, but well,… no harm done, as they say…”

Others explain some, but not all, self-care recommendations, as 85-year-old Ramona points out: “I know I can’t walk barefoot and that we shouldn’t wear open footwear… This is what another nurse told me… I’ve been seeing her for many years….”

There are also participants who claim not to have received any information at all about foot care. In this regard, 80-year-old Ramón explains: “…I’ve not been told absolutely anything whatsoever, nothing at all …not even that I have to go to the podiatrist …”

When discussing the type of information they receive, some participants expressed needing more information about diabetes and the defining aspects surrounding it. On this subject, 66-year-old Jesús explains: “I think there should be more information when they detect that a person is diabetic because doctors know that diabetes is…well, it’s not cancer, but it is a disease that nibbles away at other parts of the body.”

Information linking different symptoms to diabetes are aspects demanded by some participants. More information is requested in order to be able to detect future complications. In this sense, 80-year-old Rafael states: “…they haven’t explained it to me either… maybe some complaint or another I might have I don’t associate it with it [referring to diabetes], but if you don’t explain it to me properly, I won’t be aware of it.”

Subjects with a higher level of education have researched their health problem more. For instance, 66-year-old Jesús comments: “…I have been looking into it…I’ve gone to conferences and talks by diabetics in Catalonia and what they talked about was to sell you things and magazines…I squirrel away my money whenever I can, and I have been picking at the doctors who have been seeing me lately about my feet and diabetes.”

Regarding daily preventive self-care of the feet, people with diabetes are told that they should inspect and clean their feet daily. In the answers provided by the respondents, we can see that adherence to the recommendations on foot care is spotty, ranging from people who only wash their feet every day to those who say that they follow all the instructions. In this regard, Rafael, 80 years old, states: “I take care of them by washing them, especially when I’ve been walking… I check to see whether I have any wounds, any scratches, if one of my toenails is black …”

Other people explain how they scrupulously follow the instructions received at the clinic, in aspects such as hygiene, moisturizing, and nail care indicated. In this regard, 85-year-old Ramona points out the following: “I take care of my feet by putting cream on them every day and going to the podiatrist.”

By and large, the participants in this study reported that they performed their daily hygiene themselves and in only a few cases was care carried out by a third party, usually their partner, who is usually the main caregiver. Some respondents reported that the only foot care they practised was limited to washing their feet, not using moisturising cream afterwards, cutting their nails instead of filing them, etc. On this subject, Ramón, 80 years old, reports: “Wash them and cut my nails and that’s it …nothing else.”

In some cases, foot care involves adopting a posture that is difficult to maintain, age, joint and/ or motor problems are a drawback if there is no other person who can carry out this care. Typically, this task falls to the person living with the [diabetic] person. Jesús, 66 years old, comments: “… My wife looks to see if I have any sores, cuts, or anything else… I can’t reach [my feet] because I have a bigger belly and I’m not nimble enough to look at them…”

Patients usually go to their doctor’s and nurse’s check-ups; nevertheless, what we can see is that the person prioritises some care over others depending on personal factors, whether economic, mobility, or family reasons.

Regular visits to the podiatrist are also recommended for foot care. The respondents explained that they mostly comply with the healthcare professionals’ recommendations; however, there are some actions that do not quite coincide with these recommendations and one of them is going to the podiatrist, although most of the subjects attributed this to economic considerations. Among the participants, most go to the podiatrist with the frequency recommended by the Catalan Health Service, as this is free of charge, i.e., three times per year. However, some do not go to these visits and do not specify any reason in particular, such as 83-year-old Rosa who says: “I cut my nails myself. I don’t go to the podiatrist because for now I’m doing fine, besides…I apply cream…but between the toes.”

Others go to the podiatrist, pointing out the economic cost that entails. In this sense, 75-year-old Josefina states: “…when I have the papers [podiatrist referrals] I go to this woman, and then I go to the civic centre [she goes every month], because this woman charges Є25 and the podiatrist at the civic centre charges Є5.50 and that’s what I can afford…."

The nurse’s recommendations regarding the type of footwear include footwear that adjusts to the shape of the foot, avoiding seams, and that supports and protects the foot.

As for the use of footwear, most of which is footwear purchased for outdoors, they explain that it is usually special and adapted to the needs and shape of the foot. This is what 66-year-old Eva says: “Comfortable footwear, at least a minimum of quality, I don’t buy just any old shoes because I’ve already had experience with rubbing…”

Another of the recommendations that is not followed when it comes to foot care is wearing closed shoes at home to avoid bumps and injuries, thereby creating a risky situation while at home. Respondents explain risky behaviour even though they know that it can result in injury to limbs that are considered to be vulnerable. The reasons for these behaviours should certainly be explored further, given that they [the patients] have received information on care, and most of them are aware that what they are doing, is not consistent with the information provided, but they still accept the risk. Jorge, 68 years old, explains: “…sometimes, when I am in the village, I get cracks in the back, but it’s from walking around in flip-flops… if the heel gets a little cracked…”

With regard to footwear coverage, most explain that they usually wear appropriate footwear, with the exception of a few cases in which they report using open footwear without any protection, usually in summer and at home, explaining that closed footwear makes them hot. In this context, Carmela, 86 years old, reports: “I buy the shoes I like, although I usually wear shoes that suit my feet. At home I go up and down in flip-flops, not slippers to put my feet in, very comfortable and with my toes exposed...”

Describing the experience of diabetic foot care in patients over the age of 65 involves taking into account that there is a progression of the disease and with it, the development of diabetic neuropathy. Neuropathy results in a lack of warning symptoms which leads the patient to minimise the perception of risk. The fact that complications arise late makes it difficult to recognise risk attitudes and lifestyle modifications to facilitate prevention.1

In general, participants report that they have received little information from nurses. Still, despite the fact that systematic monitoring of the clinical aspects associated with diabetes, such as the determination of glycosylated haemoglobin or the repetition by the nurse of the information necessary for care, is carried out in nursing clinics, as indicated by Menéndez Torre et al., there is still a long way to go in the development of a model of care that covers both the clinical and psychosocial needs of these patients.14

Some authors have reported that only 10% of the participants studied adhered to all the foot care recommendations, ascribing this to the limited time devoted to explaining foot care in the doctor’s office.15 In contrast to the findings of these authors, in Catalonia (Spain), the person responsible for the follow-up visit of a person with diabetes is the reference nurse, who spends an average of 15−20 min on this appointment, inspecting patients’ feet and offering the necessary education. There may be other factors that affect participants’ implementation of self-care that would be worth probing. There are even participants who claim not to have received any information on foot care at all. In this sense, for some authors, when there is a deficit of knowledge or poor perception about the practice of self-care, the risk of undesirable self-care practices increases, which may in turn, lead to greater risk of developing a foot ulcer.16 Thus, the use of unsuitable footwear such as flip-flops poses an increased risk of causing visible injuries that are largely overlooked. It should also be noted that the information these patients receive from healthcare professionals would require a change in how the information is communicated in order to improve the perception of the disease. Similarly, the fact that some authors have correlated the level of higher education and the long evolution of DM with good foot care should also be taken into account, pointing to these aspects as significant in the practice of care.17 In our study, there are few differences with respect to foot care between people with higher and lower levels of education, but the search for information in this regard through lectures, talks, and explanations by doctors does stand out in those with higher educational levels, albeit this does not appear to establish any significant differences in foot care.

Furthermore, improved communication about foot care may also improve the detection of some symptoms that are not associated with the health problem. In this regard, Nather et al. explain that the key to preventing diabetic foot problems lies in education, mainly targeting patients and caregivers, but pointing out that practitioners must first be trained to understand the nature of patient education. Once trained and skilled, these professionals will be able to provide effective education to patients and their caregivers.18 With these educational and communication skills in mind, it should be noted that nurses in Spain who are involved in educating patients with diabetes are mostly general nurses, some of whom hold a master’s degree (although this may or may not be related to primary care) and very few hold a doctoral degree, which also does not implicitly assume a higher level of diabetes-specific knowledge. Nor does the speciality of community nursing guarantee greater expertise in managing and caring for people with diabetes or in teaching diabetes care. These statements emerge from the observation and experience of the researchers as university lecturers and knowledgeable about the curricular content of undergraduate and postgraduate nursing education. It should be pointed out that the centre where the research was carried out is a teaching centre where family and community nursing residents are trained. It can be stated that specific knowledge in this field is the responsibility of the professional’s personal interest.

A thorough assessment of DM patients’ feet is an essential tool to prevent and/ or minimise neuro-musculoskeletal and vascular complications. Therefore, as indicated by Santana da Silva et al., educational intervention strategies aim to promote DM2 patients’ learning and adopting self-care for their feet. As for preventive daily foot self-care, people with diabetes are told that they should inspect and wash their feet daily with soap and water for five minutes, rinse them well, and dry them thoroughly, especially between the toes. Avoiding walking barefoot and taking care of toenails are also recommended as part of the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) Standards of Care.19,20 Prior to using hot water, they should check the temperature with their elbow and, finally, apply moisturiser and watch for redness or other abnormalities. The use of hot water bottles or heating pads is never recommended.19 Thus, in relation to foot care, most of the respondents in this study reported that they washed their feet themselves on a daily basis, and in only a few cases was foot care handled by a third party. Some people reported that the only foot care they performed was limited to washing their feet, not using any moisturising cream afterwards, cutting the nails instead of filing them, etc. This is consistent with the results reported by Natalia de Sá et al. who stated explicitly that foot care activities such as washing, drying, moisturising, and massaging are not performed together, and in some cases are not carried out at all.9

As for proper foot care and ADA20 recommendations, most of the participants in this study performed proper foot hygiene, although some neglected to moisturise and most cut their nails instead of filing them. This is perhaps influenced by the awkward positions required for foot care and the age of the participants (over 65 years old). In the case of those who lived with a partner, the partner was the one who inspected the patient’s feet. All the female participants stated that they moisturised their feet on a daily basis, while the men considered this aspect to be less important. In this respect, some studies have found significant differences in lifestyle and self-care practices between men and women.21

For some authors there is a significant, direct correlation between knowledge and the practice of self-care, knowledge being one of the most important factors in providing quality care.22 Thus, health literacy is important to improve self-care, as it contributes to reducing complications.23 It is worth mentioning that the characteristics of the population surveyed coincide in some aspects with those of Santana da Silva et al. who found that the low level of schooling and family income were associated with the percentage of diabetics who took proper care of their feet, understanding that their level of education entails decreased understanding and consequently, limited access to information on self-care.2 In this context, some participants pointed out the lack of information dedicated to identifying the signs and symptoms that may be related to the evolution of their disease. Existing health care services and educational programmes may not adequately meet all the needs of people with DM. Some of the unmet needs identified by some authors include an emphasis on emotional and role management, being available at all times, having up-to-date evidence-based guidance for patients, and providing access and peer-generated professional advice.24

Regular visits to a podiatrist are also recommended for foot care. In this regard, the Catalan Health Service subsidises three foot check-ups a year for people with DM. This involves being evaluated by a specialist (podiatrist) for risk prevention and, therefore, does not involve any financial cost for the person. International guidelines recommend at least three levels of foot care management according to risk and each level includes podiatrist care.25 However, these researchers’ clinical practice advises that higher-risk feet should be checked by a podiatrist more frequently than this instruction provides. On the other hand, it should be noted that the podiatrist to whom these individuals go performs nail care for the patient and a thorough observation of the feet but does not inform the health professionals monitoring the patient of the findings and activities performed.

The nurse’s recommendations in relation to the prevention of a foot at risk, and as a complement to daily hygiene, are not to cut ingrown toenails or calluses and not to trim the toenails straight across. Gentle filing is emphasised and notification to the nurse is recommended in the event of swelling, redness, or ulceration, even if painless.19

Some participants noted that the cost of seeing a podiatrist is substantial. They also mention the importance of having sufficient financial resources for private services, as public health insurance does not provide the care they consider to be appropriate for their condition.7

On the other hand, the need for communication between podiatrists and nurses caring for these patients should be emphasised, with the aim of exchanging perceptions and influencing aspects of care collaboratively, as well as reporting possible injuries that could be the reason for a more thorough follow-up by the nurse.

The limitations of this study are those of qualitative research. We believe it pertinent to state that these results cannot be extended to the entire population with DM2 in the institution observed. It should also be noted that participants may not have provided full information about care because they may not have trusted the researcher.

The recommendations on foot care are transformed into an irregular attitude towards self-care, finding people who only perform daily foot hygiene to people who claim to follow all the recommended instructions. The respondents came to prioritise certain types of care over others according to personal factors, whether these were economic, mobility, or family factors. The economic aspect is comprehensively mentioned as one of the recommended measures, but not affordable for at-risk people with low income. There may be other factors contributing to the participants’ choice of self-care, which should be addressed, and which could shed light on the reasons underlying the irregularity of self-care. Surely why patients engage in certain risky behaviours should be further explored as they have received information on care, and most are aware that what they are doing does not coincide with the information provided.

Strategies are needed to systematically contact, characterise, profile, identify, and educate people who engage in these inadvisable behaviours, enforcing actions among people at greatest risk in person, as well as having channels that allow for two-way education and answering doubts related to this issue.

Finally, to conclude that treatment advice is essential for the person with diabetes to have the best possible level of health and to remain free of complications for as long as possible. Foot care is a basic pillar in this respect; nurses should provide information on self-care, using communication skills to ensure that the message is understood and that the person with diabetes puts it into practice.

Ethical considerationsThis project has been approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the IDIAP Jordi Gol i Gurina, with code P18/106 at the meeting held on 25 July 2018. All participants were informed of the project both verbally and by means of an informative letter and subsequently signed the informed consent form.

FundingThis project has not received any kind of financial aid for its execution.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of economic interests or personal relations to declare that may have affected the information reported in this.

The research team would like to thank all the participants in this study for their selfless time in sharing their personal experiences and aspects of the care and self-care required in relation to their diagnosis of diabetes.