Efforts have recently been made in Spain to improve the communication model between primary care and specialized care. The aim of our study was to analyze the impact of a change in the communication model between the two areas when comparing a traditional system to a consulting system in terms of satisfaction of general practitioners and the number of patient referrals.

MethodsA questionnaire was used to assess the point of view on the relations with the endocrinologist team of 20 general practitioners from one primary care center at baseline and 18 months after the implementation of the new method of communication. In addition, we counted the number of referrals during the two periods.

ResultsWe analyzed 30 questionnaires; 13 before and 17 after the consulting system was established. Consulting system was preferred to other alternatives as a way of communication with endocrinologists. After the consulting system was implemented, general practitioners were more confident in treating hypothyroidism and diabetes. There was a decrease in the number of patient referrals to specialized care from 93.8 to 34.6 per month after implementation of the consultant system.

ConclusionsThe consultant system was more efficient in resolving problems and responding to general practitioners than the traditional system. General practitioners were more confident in self-management of hypothyroidism and diabetes. A very large decrease in the number of patient referrals was observed after implementation of the consultant system.

En los últimos años se ha intentado mejorar en España la comunicación entre la atención primaria y la atención especializada. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar el impacto de un cambio en el modelo de comunicación entre ambas áreas, comparando el sistema tradicional con un sistema de consultoría. Se analizó la satisfacción de los médicos de atención primaria y el número de derivaciones realizadas.

MétodosEn un centro de atención primaria donde trabajan 20 médicos, se pasó un cuestionario al inicio y a los 18 meses de introducir un sistema de consultoría, para conocer su punto de vista sobre la relación con el equipo de endocrinología. Asimismo se contabilizó el número de derivaciones durante ambos períodos.

ResultadosSe analizaron 30 cuestionarios: 13 al inicio y 17 tras el establecimiento del sistema de consultoría. El nuevo sistema se prefirió a otras alternativas como medio de comunicación con los endocrinólogos. Tras la introducción del sistema de consultoría, los médicos tenían más confianza y autonomía en la gestión de la diabetes y el hipotiroidismo. Además disminuyó drásticamente el número de derivaciones a la atención especializada, que pasó de 93,8 a 34,6 pacientes por mes tras la introducción del sistema de consultoría.

ConclusionesEl sistema de consultoría resultó más eficaz que el sistema tradicional para la resolución de problemas y la respuesta a los médicos. Los médicos aumentaron la confianza y autonomía en la gestión de la diabetes y el hipotiroidismo. Se observó un descenso importante del número de derivaciones.

The interaction between primary care (PC) and specialized care (SC) is not a trivial issue and becomes even more important when chronic diseases are involved.1,2 The lack of coordination between both areas has historically been a shortcoming in the Spanish health system.2 Recently, to address these shortcomings, a medical consultant (MC) role has been proposed. An integrated care model is the key to delivering high-quality care, which is important for patients and physicians.3–5 Although this is a very important issue, few groups have studied how to improve the communication between PC and SC in the last 10 years2,5,6; however, there has been increasing interest in this issue given that most of the related studies have been published in the last 4 years.7–14

Our hospital is the largest hospital in Catalonia and the second in the Spanish State. It is located in the north of Barcelona city, and its influence area includes: six districts, with a population of over 450,000 inhabitants. To improve the quality of care and avoid movements to patients, in general, hospital's specialists are who move and perform their activities in different primary care centers of the hospital's area.

The way to interact specialist care and primary care could be by traditional system (TS) or consulting system (CS). We define as a TS, the model in which the specialist moves to the PC center and checks all referrals without interacting with GPs. In contrast a CS, is the model in which the MC moves to PC centers and gives training sessions and meetings to GPs, promotes self-management and only high complexity patients are referred to SC. By taking advantage that a new primary care center with an approximately reference area of 42,000 habitants will be linked to our hospital, we were able to change the communication model from TS to a CS and to evaluate this change.

To the best of our knowledge no studies have analyzed the impact of changing the communication system from a TS to a CS between the PC and SC in terms of general practitioner (GP) satisfaction and the number of referrals. Therefore, the aim of our study was to analyze the impact of changing communication systems between the PC and SC from a TS to a CS in terms of GP satisfaction and the number of patient referrals.

Materials and methodsA longitudinal study was conducted in one PC center, with an approximately reference area of 42,000 habitants, where 20 GPs were working. This center planned a communication system change from a TS to a CS. We asked the GPs to voluntarily and anonymous participate in a survey.

The questionnaire was designed specifically for this study and was focused on coordination points between PC and EC and in the two most common diseases approach of our specialty. The questions were performed from prior self-reported items of the two groups and with elements of previous papers.2,8,9

The GPs answered the questionnaire twice (before and 18 months after the new CS was implemented). The first questionnaire was distributed in February 2011 and the second questionnaire was distributed in September 2012.

Questionnaire descriptionThe survey consisted of 21 questions with subsections addressing different areas of interest. In general, the possible answers to each question ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 representing “very bad” and 5 representing “very good”. To facilitate reading the results, we grouped the results into the following two categories: “bad” included “very bad”, “bad”, or “neutral;” and “good” included “very good” and “good.”

The first six questions were related to GPs feeling/perception of the communication system in terms of experience, feed-back, accuracy and appropriate timely response to medical referrals whit endocrine and with other specialties.

The next six (from 7 to 12) inquired about educational material received, preferred way of contact with SC and relevant abilities that a consultant endocrinologist should have whit endocrine and with other specialties.

The following questions were dedicated to the most common diseases our specialty deals with (diabetes and hypothyroidism) which are the ones that the GP most frequently faces: from 13 to 15 the questions were related with hypothyroidism and from 16 to 20 opinions about the management of a diabetic patient with oral agents or insulin were asked.

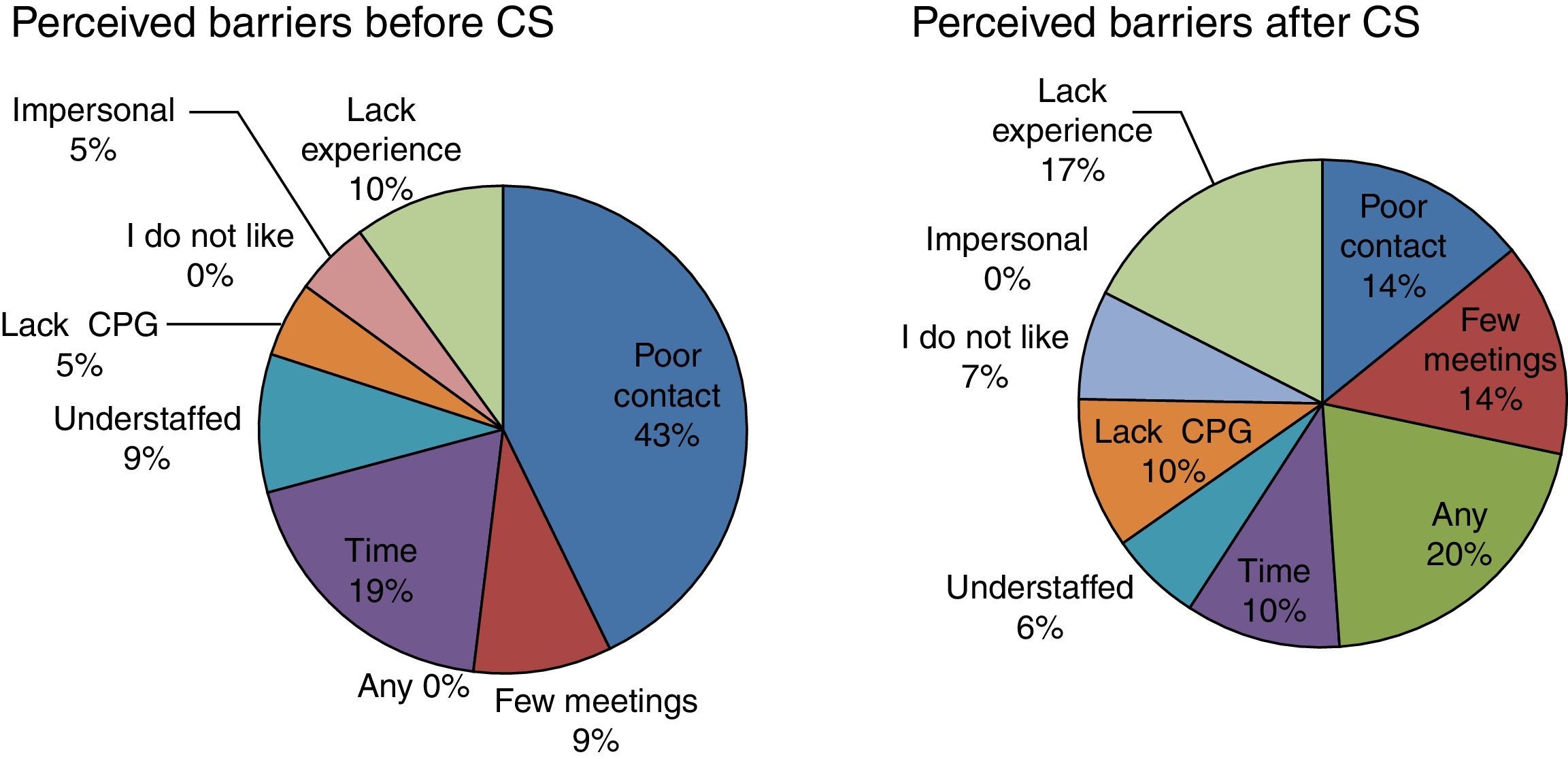

In the last question (number 21) potential perceived barriers to the successful development of a CS by the GPs were listed. This one was a multiple-choice answer.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 19.0 statistical package for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). We assessed the differences between sub-groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test (non-Gaussian distribution) and Fisher's exact test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

The study was conducted in accordance with the policy and mandates of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guide for Good Care.

ResultsThirty freely anonymous questionnaires were analyzed from the 20 GPs working in the PC center. Thirteen questionnaires were answered before and 17 questionnaires were answered after the change to the new communication system.

- (a)

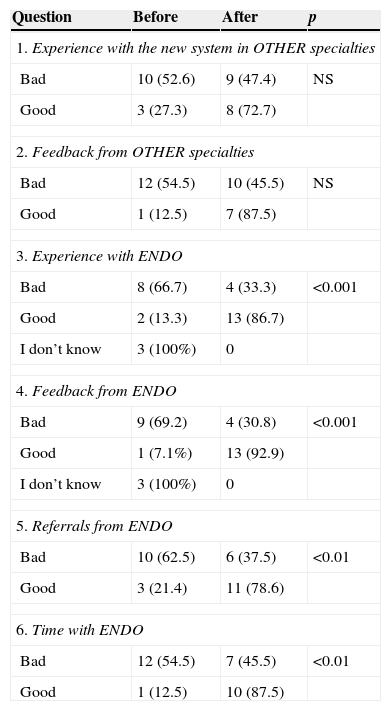

Based on questions 1–6, the opinions of the GPs about the CS were evaluated. No changes were noted before and after the switch to the new system with “other” specialties, but improved feelings were apparent with the “endocrinology” CS for all items (Table 1).

Table 1.Questions 1–6: general practitioners’ feelings regarding the consultant system.a

Question Before After p 1. Experience with the new system in OTHER specialties Bad 10 (52.6) 9 (47.4) NS Good 3 (27.3) 8 (72.7) 2. Feedback from OTHER specialties Bad 12 (54.5) 10 (45.5) NS Good 1 (12.5) 7 (87.5) 3. Experience with ENDO Bad 8 (66.7) 4 (33.3) <0.001 Good 2 (13.3) 13 (86.7) I don’t know 3 (100%) 0 4. Feedback from ENDO Bad 9 (69.2) 4 (30.8) <0.001 Good 1 (7.1%) 13 (92.9) I don’t know 3 (100%) 0 5. Referrals from ENDO Bad 10 (62.5) 6 (37.5) <0.01 Good 3 (21.4) 11 (78.6) 6. Time with ENDO Bad 12 (54.5) 7 (45.5) <0.01 Good 1 (12.5) 10 (87.5) - (b)

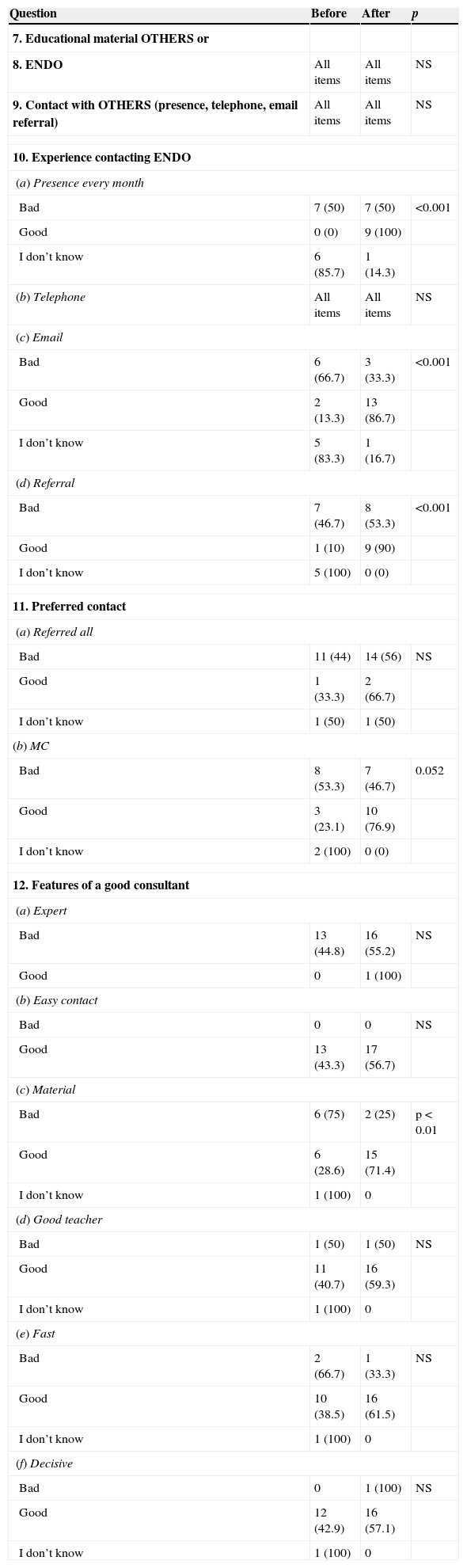

Based on questions 7–12, we evaluated the educational material received, preferred contact with SC, and relevant features that a consultant endocrinologist should have. There was no difference in the quality of delivered material by endocrinology or other specialties. No differences were found in the preferred way to contact with other specialties, but a change of preferences contact to the consultant endocrine was found. Finally, not differences checked in the relevant characteristics that must have a consultant (Table 2).

Table 2.Questions 7–12: educational material and requirements that an endocrinologist consultant should have according to general practitioners’ preferences. The table shows the responses obtained before and 18 months after the implementation of the new consultant system.

Question Before After p 7. Educational material OTHERS or 8. ENDO All items All items NS 9. Contact with OTHERS (presence, telephone, email referral) All items All items NS 10. Experience contacting ENDO (a) Presence every month Bad 7 (50) 7 (50) <0.001 Good 0 (0) 9 (100) I don’t know 6 (85.7) 1 (14.3) (b) Telephone All items All items NS (c) Email Bad 6 (66.7) 3 (33.3) <0.001 Good 2 (13.3) 13 (86.7) I don’t know 5 (83.3) 1 (16.7) (d) Referral Bad 7 (46.7) 8 (53.3) <0.001 Good 1 (10) 9 (90) I don’t know 5 (100) 0 (0) 11. Preferred contact (a) Referred all Bad 11 (44) 14 (56) NS Good 1 (33.3) 2 (66.7) I don’t know 1 (50) 1 (50) (b) MC Bad 8 (53.3) 7 (46.7) 0.052 Good 3 (23.1) 10 (76.9) I don’t know 2 (100) 0 (0) 12. Features of a good consultant (a) Expert Bad 13 (44.8) 16 (55.2) NS Good 0 1 (100) (b) Easy contact Bad 0 0 NS Good 13 (43.3) 17 (56.7) (c) Material Bad 6 (75) 2 (25) p<0.01 Good 6 (28.6) 15 (71.4) I don’t know 1 (100) 0 (d) Good teacher Bad 1 (50) 1 (50) NS Good 11 (40.7) 16 (59.3) I don’t know 1 (100) 0 (e) Fast Bad 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3) NS Good 10 (38.5) 16 (61.5) I don’t know 1 (100) 0 (f) Decisive Bad 0 1 (100) NS Good 12 (42.9) 16 (57.1) I don’t know 1 (100) 0 Numbers are expressed in absolute values and percentages in parentheses. ENDO: endocrinology; MC: medical consultant.

- (c)

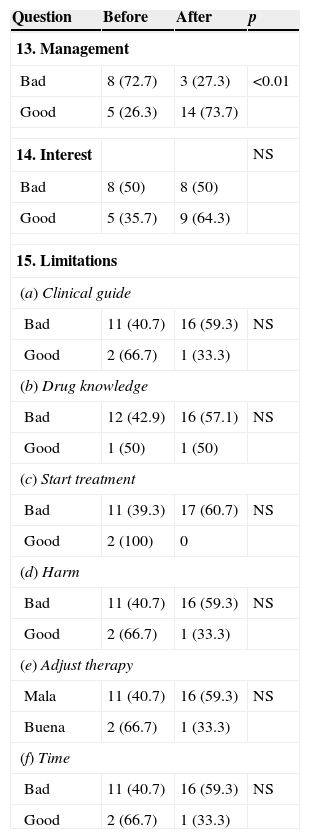

Based on questions 13–15, management of hypothyroidism was evaluated.GPs felt more comfortable with the management of hypothyroidism after the CS was implemented but their interest or limitation did not change (Table 3).

Table 3.Questions 13–15: evaluations about thyroid management according to GPs’ opinions. The table shows the responses obtained before and 18 months after the implementation of the new consultant system.

Question Before After p 13. Management Bad 8 (72.7) 3 (27.3) <0.01 Good 5 (26.3) 14 (73.7) 14. Interest NS Bad 8 (50) 8 (50) Good 5 (35.7) 9 (64.3) 15. Limitations (a) Clinical guide Bad 11 (40.7) 16 (59.3) NS Good 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3) (b) Drug knowledge Bad 12 (42.9) 16 (57.1) NS Good 1 (50) 1 (50) (c) Start treatment Bad 11 (39.3) 17 (60.7) NS Good 2 (100) 0 (d) Harm Bad 11 (40.7) 16 (59.3) NS Good 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3) (e) Adjust therapy Mala 11 (40.7) 16 (59.3) NS Buena 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3) (f) Time Bad 11 (40.7) 16 (59.3) NS Good 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3) Numbers are expressed in absolute values and percentages in parentheses. GP: general practitioner.

- (d)

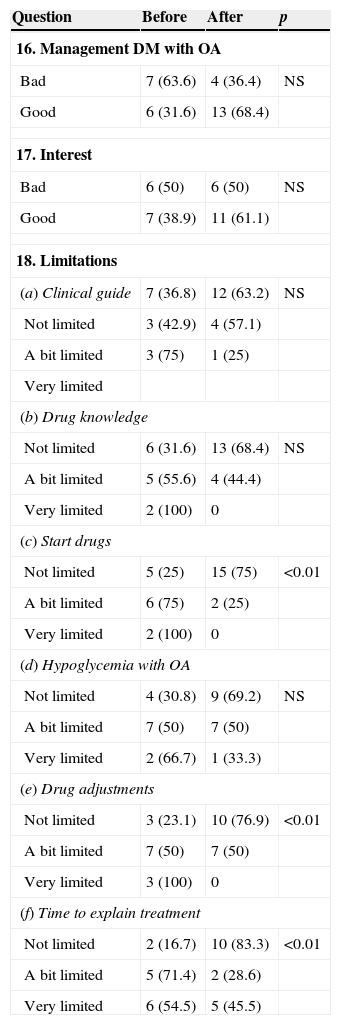

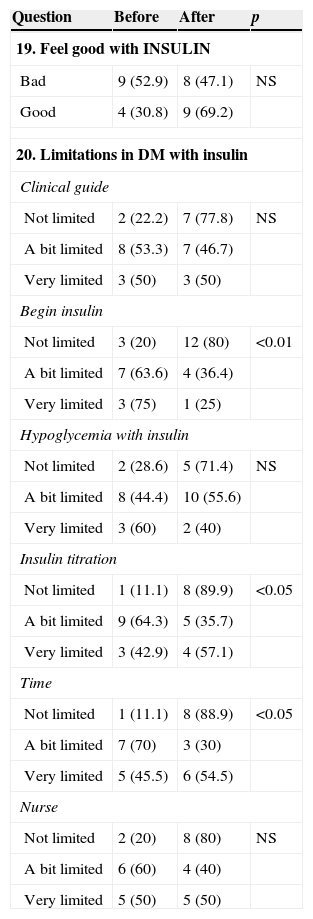

Based on questions 16–20, we evaluated diabetes management (Tables 4 and 5).The GPs felt more confident in starting or adjusting oral agents or insulin doses and with the time expended in the management of diabetic patients with oral agents or insulin therapy after the CS was implemented No statistically significant differences were detected in the other aspects analyzed.

Table 4.Questions 16–18: evaluations about diabetes management with oral agent. The table shows the responses obtained before and 18 months after the implementation of the new consultant system.

Question Before After p 16. Management DM with OA Bad 7 (63.6) 4 (36.4) NS Good 6 (31.6) 13 (68.4) 17. Interest Bad 6 (50) 6 (50) NS Good 7 (38.9) 11 (61.1) 18. Limitations (a) Clinical guide 7 (36.8) 12 (63.2) NS Not limited 3 (42.9) 4 (57.1) A bit limited 3 (75) 1 (25) Very limited (b) Drug knowledge Not limited 6 (31.6) 13 (68.4) NS A bit limited 5 (55.6) 4 (44.4) Very limited 2 (100) 0 (c) Start drugs Not limited 5 (25) 15 (75) <0.01 A bit limited 6 (75) 2 (25) Very limited 2 (100) 0 (d) Hypoglycemia with OA Not limited 4 (30.8) 9 (69.2) NS A bit limited 7 (50) 7 (50) Very limited 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3) (e) Drug adjustments Not limited 3 (23.1) 10 (76.9) <0.01 A bit limited 7 (50) 7 (50) Very limited 3 (100) 0 (f) Time to explain treatment Not limited 2 (16.7) 10 (83.3) <0.01 A bit limited 5 (71.4) 2 (28.6) Very limited 6 (54.5) 5 (45.5) OA=oral agent; numbers are expressed in absolute values and percentages in parentheses.

Table 5.Questions 19–20: evaluations about diabetes management with insulin. The table shows the responses obtained before and 18 months after the implementation of the new consultant system.

Question Before After p 19. Feel good with INSULIN Bad 9 (52.9) 8 (47.1) NS Good 4 (30.8) 9 (69.2) 20. Limitations in DM with insulin Clinical guide Not limited 2 (22.2) 7 (77.8) NS A bit limited 8 (53.3) 7 (46.7) Very limited 3 (50) 3 (50) Begin insulin Not limited 3 (20) 12 (80) <0.01 A bit limited 7 (63.6) 4 (36.4) Very limited 3 (75) 1 (25) Hypoglycemia with insulin Not limited 2 (28.6) 5 (71.4) NS A bit limited 8 (44.4) 10 (55.6) Very limited 3 (60) 2 (40) Insulin titration Not limited 1 (11.1) 8 (89.9) <0.05 A bit limited 9 (64.3) 5 (35.7) Very limited 3 (42.9) 4 (57.1) Time Not limited 1 (11.1) 8 (88.9) <0.05 A bit limited 7 (70) 3 (30) Very limited 5 (45.5) 6 (54.5) Nurse Not limited 2 (20) 8 (80) NS A bit limited 6 (60) 4 (40) Very limited 5 (50) 5 (50) Numbers are expressed in absolute values and percentages in parentheses.

- (e)

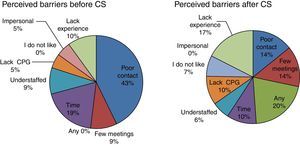

Question 21 addressed the main barriers to establish a CS (Fig. 1).Before establishment of the CS, the main reported barriers were poor contact and lack of time due to the amount of work. After implementation of the CS, the most reported barriers were the lack of experience in this new contact; most GPs did not express any barrier with the new system.

Finally, two years after the new CS was set up, we observed more than three times fewer referrals than the previous period with the TS. The number of referrals dropped from 563 during the first six months of 2011 to 116 in the same period of 2013.

DiscussionIn the current study, 18 months after the CS was implemented, GPs felt more comfortable than with the previous communication system (TS). The GPs were more comfortable in self-management of diabetes and thyroid disease and a significant drop in the number of patient referrals to the SC was observed. Furthermore, the GPs thought they provided better solutions to patient problems.

This study gave GPs the opportunity to voice their opinion and their job role in relation to a new implemented CS. The survey was anonymous and voluntary. A higher participation was observed after implementation of the MC system (13/22 before and 17/22 after). We interpret this fact as an increase of GP's interest and satisfaction.

The main weakness of the study was that it was performed in only one PC area, which limited the sample size. Furthermore, it was not possible to perform a paired study due to the differences in the number of responders between both periods evaluated, and also because the survey was blind, voluntarily and anonymous. Additionally, the questionnaire was only designed specifically for the study. Therefore, the results cannot be extrapolated to other situations.

The CS is a good tool with which to improve communication between PC and SC. However, the MC and GP profiles are essential for success in CS implementation. Experience and accessibility is required for the MC profile. The MC will provide training to the GP team. In contrast, GPs must be motivated, receptive, and autonomous. Furthermore, specific time frames for this task and referral protocols should be clearly defined. For proper CS development, it would be essential to include regular training meetings with endocrinologists at PC centers. These meetings should include clinical sessions to discuss clinical cases, theoretical sessions, monitoring treatment and referral protocols. We are implementing the CS in more PC centers in two different manners (presence CS and virtual CS) and we also plan to extend the study in the near future. We conclude that good coordination between PC and SC is essential, and especially important in chronic diseases, such as diabetes. The CS and GP training increase GP autonomy, satisfaction, and improves treatment of diseases. CS leads to a decrease in the number of referrals, thus allowing the SC to focus on more complex pathologies and to be able to respond more effectively and more rapidly to GP requirements.

Role of fundingNo financial support.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest disclosed for any author.

Presentation in a local meeting as a poster: Plà de Salut de Catalunya 2013.