Online platform working, Gig working, E lancing and Moonlighting have become synonymous in the Industry 4.0. Searching for and practicing alternative employments is an important phase in recording the sequence of employees’ withdrawal cognitions (WC). WC have been studied in the past majorly in relation with job attitudes for the ultimate consequence of turnover but in this virtual era, it is equally considerable to investigate the relationship of job attitudes with this important cognition sequenced before turnover stage, i.e. moonlighting, which may ultimately lead to turnover. This paper proposes to conduit the research gap of investigating the effect of Job Satisfaction on Moonlighting Intentions and the mediating effect of Organizational Commitment between these two variables. SmartPLS 3.0 software has been used to execute partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) for the research framework on a sample of 161 IT professionals working in the North Indian IT hubs of N.C.R. Delhi and Chandigarh. In the present study, four hypotheses have been employed for examining the relationships among the variables Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Moonlighting Intentions. PLS –SEM supported all of them. Organizational Commitment has a mediating effect between Job Satisfaction & Moonlighting Intentions while Job Satisfaction puts a very high positive impact on Organizational Commitment. In addition, Organizational Commitment shows a very significant inversely proportionate relationship with Moonlighting Intentions.

Moonlighting and gig working have been phenomenal in the I.T. sector due to the increasing proliferation of internet companies and their employee-friendly work practices. Moonlighting or multiple job holding is referred to as the practice of working for a second job additional to the primary job, which is done either at the cost of primary job working hours or in the free time after that (Ashwini et al., 2017; Yamini & Pushpa, 2016). In the current digital era, organizations also opt for letting out gigs in lieu of reasons like cost cutting, benchmarking of quality standards and business process reengineering etc. Moonlighting has become such a challenge for the Human Resource Management function that it requires many thoughtful interventions to ensure effective work performance by the employees while simultaneously supporting them in the opportunities for self-growth and development.

New designations have evolved in the HRM functions to manage gig working from both the organizational and workforce perspectives. Microsoft, the biggest I.T. giant came up with the world’s first Gig economy manager Mr. Liane Scult who now works with the most sought after e-lancing platform company Upwork. With the rapid changes in socio-economic systems in current scenarios, there would be many more such roles in HRM domain. Gig economy strategist, future of work manager, second-act coach are a few titles among them (Dennis, 2020).

As I.T. sector is always dynamic towards sudden massive layoffs due to rapid technology up gradations and less motivating opportunities for freshers, it possesses the hardest competition of survival of the fittest for the digital knowledge workers. Here, only those survive who keep gaining the most contemporary knowledge, skills and abilities (KSA’s). The only way out for these knowledge workers to survive in their job market and to sustain their highly paid primary jobs is to keep searching challenging alternative opportunities mostly with internet firms and attempting moonlighting with them to design their skill based portfolio careers. This is because the focus of both the employees and the employers in the knowledge century is shifting from job security to skill based employment security (Fatimah et al., 2012). So, HR functions of this industry need to be extra proactive in reengineering their work practices to keep their key learning employees retained (as the lay-offs generally happen to the workforce with obsolete skill-sets) and their turnover intentions minimized which may be triggered by their moonlighting practices (Ashwini et al., 2017).

Both the developed and developing economies face the dynamics of moonlighting in their shadow or gig economy. In all economies, I.T. industry specifically has witnessed a significant rise in moonlighting practices of its workforce due to the provision of various employee friendly work-life-balance initiatives. That is why moonlighting has become its important labor market phenomenon (Ashwini et al., 2017). This practice is generally initiated by the workforce from partial moonlighting and is gradually transformed to full moonlighting subject to the person’s motives behind it. Partial or quarter moonlighting means a few hours spent on the second job after an employee has wound up one’s first job. However, when one wants to increase the moonlighting hours, it can be done by spending 50 percent of the work hours in the secondary job. And finally when the individual has decided to shift one’s career from primary to secondary occupation or an entrepreneurship venture, one would devote all the time into the secondary job or the proprietary venture and stays on the primary occupation only to treat it as a shock absorber in case the venture fails (Sangwan, 2014).

People can have various kinds of motives behind moonlighting and these motives decide about the nature of their moonlighting practice i.e. persistent or transitory. Persistent moonlighters always practice moonlighting for some particular benefits and don’t aspire to transform their primary occupations through moonlighting but transitory moonlighting is done to shift careers into the secondary employments after gaining requisite skills from them (Sangwan, 2014).

Most common reason for practicing moonlighting; cited in the literature is financial strain but non-pecuniary priorities arisen through the modern lifestyle also persuade a person towards multiple job holding at the same time. This paper aims to discuss the role of other two non-pecuniary motives behind moonlighting, including job satisfaction & organizational commitment and investigate the mediating effect of organizational commitment between job satisfaction & moonlighting intentions.

2Theoretical foundationEmployees have been regarded as the most important stakeholders of any organization. They can be the game changers for the success or failure of their firms as they affect and are affected by the organizational set-up (Azim, 2016). The relationship between an employee and his/her corresponding organization has been seen as a form of social exchange for a significant period of time (Blau, 1964). Social Exchange Theory (SET) is the most widely used theoretical agenda for explaining the relationship between the perception of organizational provisions and employees’ behavioral reactions to them (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Hogg & Terry, 2000; Molm & Cook, 1995; Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Blau, 1964). According to SET, social behavior of individuals is mostly the result of the exchange process between two individuals or an individual and his/her organization. This exchange is referred to as the reciprocity of behavior (Konovsky & Pugh, 1994). Particularly, when employees feel contented working in an organization, they are possibly supportive to their organization as a mutual exchange. This way SET provides a significant theoretical rationale for explaining the phenomenon of employee engagement within an organization (Saks, 2006). Engagement has been described as a two way association between an employer and an employee through which employees repay the cognitive, physical and emotional resources in their work-roles based upon the emotional and socio-economic resources retrieved from the organization (Robinson et al., 2004). Based on this description of SET, when the organizations meet the employees’ expectations, employees automatically feel enthusiastic towards their workplace roles and attitudes in the forms of increased sense of employee engagement, organizational commitment and other positive behaviors as desired by the organizations (Organ & Lingl, 1995). So, it can be inferred from SET that when employees feel high job satisfaction due to greater provisions offered to them by the employer, they exhibit high organizational commitment and tend to avoid or minimize the intentions to work for secondary jobs or organizations i.e. Moonlighting and the intentions to quit the job.

The second significant theoretical foundation underlying the present research is the ‘Attitudes and Alternatives Model’ (AAM) of Withdrawal Cognitions. This model explains turnover due to dissatisfaction in the broader aspect and its related antecedents (which also include searching for alternative employments and intending to moonlight) and the possible consequences (March & Simon, 1958; Mobley, 1977; Steers & Mowday, 1981; Blau, 1993; Griffeth & Hom, 1995; Price & Mueller, 1981; Mitchell et al., 2001).

All of these traditional models of turnover due to dissatisfaction contain a common six-stage sequence of withdrawal cognitions. These include starting stimulation of quitting thoughts, heading to the assessment of expected search utility, development of searching intentions, searching alternative jobs, assessment of alternatives through various approaches which may include short periods of moonlighting, quitting intentions, and ultimately withdrawal decision and execution in behavior. The above-mentioned model possesses two broad categories of variables for prediction. The first one emphasizes on the job attitudes including job satisfaction and organizational commitment and the second one emphasizes upon the ease of movement within employments that is described in perceived alternative job opportunities and the related behavior of job search (including searching for secondary alternative jobs i.e. moonlighting). It has been witnessed that when employees have stronger intentions to search for alternative jobs, there is a considerable effect of leaving the current employment (Holland, 1992; Griffeth et al., 2000; Steel & Griffeth, 1989).

This model explains the broad outlines of employees’ participation and withdrawal process in the organizational decision-making. This explains the sequence of withdrawal cognitions of employees vide which the thinking of leaving the primary jobs and intentions for searching and starting alternative or secondary employments is taken up generally by the employees due to job-dissatisfaction (Tett & Meyer, 1993; Mobley et al., 1978). This model has witnessed further developments for the linkages between alternative & multiple job holding (moonlighting) and turnover by the recent researchers (Bressler, 2010; Jamall, 1986; Rispel et al., 2014; Van de Klundert et al., 2018; Kipkebut, 2013; Betts, 2006; Koomson et al., 2017; Zimmerman et al., 2020). These all works infer that moonlighting is a significant precursor towards turnover of the employees.

Although the research regarding turnover theories and their empirical evidences specifically between job attitudes and turnover has been exponential but the investigations about the job attitudes and the ease of movements within employments, specifically intentions to moonlight requires much more attention in future works. As in this virtual industry 4.0, moonlighting and skill-based gig working is going to be the new normal demanding a great deal of platform and crowd-working (De Stefano, 2015). This would also be very much evident in the current and post pandemic virtual working.

The authors have attempted to address this research gap in the present study and strived to study the relationship between Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Moonlighting Intentions of the employees working in the domain of IT sector in North India. The review of previous literature has been divided into three parts with respect to the variables under investigation for the present study. These include moonlighting intentions of employees in relation to their job satisfaction and organizational commitment and the mediating function of organizational commitment between job satisfaction and moonlighting intentions.

2.1Job satisfaction and moonlightingJudge and Klinger (2008) have described the concept of Job satisfaction as “the subjective well-being at work”. Generally, job satisfaction refers to one’s satisfaction from his/her job related factors.

Ara and Akbar (2016) have found out that employees always want to have addition in their income if they are not offered robust performance and promotion policies in their primary jobs. They also see it as an alternative to increase job satisfaction. Double jobbing here provides them with that opportunity to earn extra and increase their job satisfaction. This indicates that people who do moonlighting strive for greater job satisfaction that they could not relish in their primary jobs.

Ronan et al. (1977) have done a study to find out relationship of moonlighting to job dissatisfaction in Police officers. He has claimed that the subjects of his study do multi-jobbing because they do not get the job satisfaction they think they deserve as law enforcement officers. The results have revealed that job-enrichment incentives can prove to be much beneficial in alleviating the job dissatisfaction in the police officials. This implies that police officers do moonlight to increase or enjoy job satisfaction in their secondary jobs.

Voydanoff and Kelly (1984) have investigated about the determinants of work related family problems among employed parents and researched about its various dynamics including moonlighting and job satisfaction. The results reveal that the parents who do multi-jobbing are simultaneously striving for job satisfaction and work-life balance for the family. Here, job satisfaction interplays between moonlighting, self-satisfaction and time for family commitments that is important for a healthy life.

Santangelo and Lester (1985) have stated that moonlighting behavior and demographic variables do not relate significantly to job-dissatisfaction, rather psychological variables like locus of control and stress were found to be more strongly correlated to job dissatisfaction. Their study implies that a direct alliance may or may not exist between job satisfaction level and moonlighting habits of the employees.

Most of the reviews about the association of moonlighting and job satisfaction suggest that most of the employees go for moonlighting for gaining that job satisfaction in their secondary jobs, which they could not achieve in their primary jobs.

2.2Organisational commitment and moonlightingMowday et al. (1979) have defined organizational commitment as “the relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in the organization”.

Ashwini et al. (2017) have studied the intentions of moonlighting of middle level employees of selected I.T. firms in southern India. They have investigated various factors forcing the workforce to practice moonlighting and concluded that in absence of proactive retention benefits to the committed employees who are experienced & loyal, their organizational commitment is lost and they go for secondary job holding to pursue their personal ambitions.

Khatri and Khushboo (2014) have conducted a research on examining the organizational commitment and moonlighting exercises of the employees of small & medium enterprises (SME) in the Delhi-NCR region of India and have estimated that organizational commitment and loyalty is definitely impacted upon if people do moonlighting for making extra income, which is very much common in SME. They have also analyzed the differences in the perception of organizational commitment by both the genders in the moonlighting employees but found no significant difference.

Jamall (1986) has studied the personal, social & organizational consequences of moonlighting among the blue-collar workers. The analysis of the study infers about workers’ organizational commitment that non-moonlighters showed much higher organizational commitment than moonlighters. This means that while working on secondary jobs, the moonlighters tend to be less committed towards their primary organizations.

All the reviews about organizational commitment towards moonlighting suggest that in absence of proactive engagement and retention initiatives to be extended by the management, employees tend to do moonlighting ultimately compromising with their organizational commitment.

2.3The mediating role of organisational commitmentTett and Meyer (1993) firstly conceptualized and investigated the mediation models placing the organizational commitment as mediator between job satisfaction and withdrawal cognition (including all the levels of withdrawal which also includes alternative employment searching and practicing i.e. moonlighting). They have identified three theoretical perspectives in this area for research implications. First is the view that organizational commitment develops from job satisfaction and organizational commitment is the mediating variable with the job satisfaction effects and the withdrawal variables. Second view is the reverse of the first, which says that organizational commitment mediates between withdrawal variables and job satisfaction. The third view describes about the unique contribution of both job satisfaction and organizational commitment. However, in their investigation of mediation by organizational commitment between broader measure of withdrawal cognition (containing all steps of withdrawal process including alternative jobbing & turnover) and job satisfaction, the mediating relationship was found slightly considerable and this mediating model was not taken much ahead for further advancements. But in the current knowledge century, the vast scope of platform gig working and online moonlighting in the virtual work arrangements calls for a further investigation of this mediation model. The reason behind is significant rise of online gig working and moonlighting in virtual work-arrangements in the current scenarios of industry 4.0 (De Stefano, 2015).

It is also worthy to note that in the theoretical foundation, the research regarding job attitudes and turnover has been mounting; various researchers have investigated organizational commitment as a mediator between job satisfaction and turnover Intentions (Samad & Yusuf, 2012; Vandenberg & Nelson, 1999; Sager et al., 1998; Meyer & Allen, 1997; Igharia & Greenhaus, 1992; Koslowsk, 1991; Salanick & Pfeffer, 1978). All these researchers have concluded that organizational commitment significantly mediates the association of job satisfaction and turnover intentions. But turnover intention is only the second last step in the sequence of withdrawal cognitions (March & Simon, 1958). Before this step, searching and working simultaneously for alternative or secondary employments (i.e. moonlighting intentions and moonlighting) is a significant milestone before thinking to quit the primary organization but this has been meagerly studied in relation with the job attitudes like job satisfaction and organizational commitment; specifically placing the organizational commitment as the mediator.

This paper aims to fulfill this space through empirical evidence, by placing the organizational commitment as a mediator between job satisfaction and moonlighting intentions.

3Research objectivesThe present research undertakes to achieve the following purposes:

- 1

To estimate the effect of Job Satisfaction on Organisational Commitment of the IT Professionals.

- 2

To study the impact of Organisational Commitment on Moonlighting Intentions of the target group in the study.

- 3

To investigate the ramification of Job Satisfaction on Moonlighting Intentions of the sample population of the study.

- 4

To ascertain the mediating effect of ‘Organizational Commitment’ allying Job Satisfaction & Moonlighting Intentions.

After formulating the objectives of the study based on the research gaps identified through the literature review, following hypotheses have been proposed by the researchers:

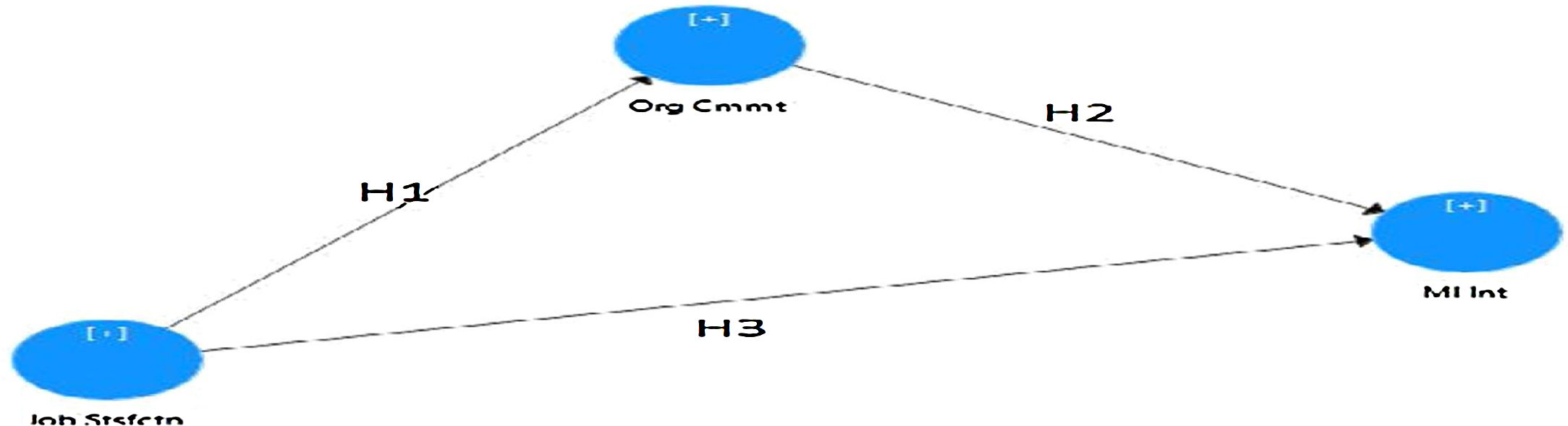

H1: Job Satisfaction has a significantly high effect on Organizational Commitment.

H2: Organizational Commitment has a significantly high impression on Moonlighting Intentions.

H3: Job Satisfaction has a significantly high ramification on Moonlighting Intentions.

H4: Organizational Commitment subtends a mediating effect between Job satisfaction and Moonlighting Intentions.

Fig. 1 shows the hypothesized research framework made by the researcher on the basis of review of literature where ‘Job Stsfctn’ denotes Job Satisfaction, ‘Org Cmmt’ denotes Organizational Commitment and ‘MI Int’ stands for Moonlighting Intentions.

4.1Description of instrumentsStandardized scales were used to measure Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment.

The Organizational Commitment is measured utilizing the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) formulated on likert scale by Mowday et al. (1979). Authors have adapted its four items in the present study with representation of possible emotions that employees might possess for the firm in which they serve. The test-retest reliability as reported by the authors is 0.75.

Job Satisfaction scale is adapted from Brayfield and Rothe (1951) originally formulated Job Satisfaction Questionnaire. Seven items have been adapted from this scale whose scoring labels from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ on the likert scale only. Author reported 0.87 reliability of the scale.

Moonlighting Intentions scale has been adapted from Seema and Sachdeva (2020), after interviewing fifteen volunteer I.T. professionals who showed intentions to moonlight. It was subjected to reliability and validity test before placing it for final data collection & analysis for the study. The scale comprises of 07 items on likert scale. The reliability value was 0.908 for this scale.

4.2Determining Sample size and collection of dataThis study specifically targets the IT professionals as sample subjects for the research in the north Indian regions of N.C.R. Delhi and Chandigarh. A total of 250 sets of questionnaire surveys were dispersed to the professionals working in IT firms in both these areas, out of which sixty four percent i.e. only 161 could be finally deemed fit for this study after dumping the inappropriate responses.

There are several schools of thoughts on taking the call about the minimum sample size for a study to be executed by using PLS-SEM software application due to its unique patronage provided under a variety of conditions of non-normality and its greater ability to execute operations for small and medium sample sizes. So, for the present study containing 3 latent constructs, the following schools of thought were able to help in the decision for the minimum sample size required to conduct the research.

Ten times thumb rule method is extensively used in PLS-SEM for estimation of required minimum sample size (Hair et al., 2013). This method assumes that the sample size estimation of any SEM study should be somewhat larger in number than ten times of the highest figure of links or arrow directions in an inner or outer structural model triggering or pointing towards any of the latent constructs in the model. This process would estimate the required minimum sample size for the present study as 10 multiply by 2 (highest quantity of directional arrows pointing at a latent construct) gives us the number as 20. Although this method appears to be easy to execute but may sometimes escort the users to unsteady estimates (Goodhue et al., 2012).

Further, the most latest and acceptable technique of sample size estimation popular among the contemporary scholars is the ‘Inverse Square Root Method’ (Kock & Hadaya, 2018). This technique has an assumption that any of the path coefficient implies to a true effect that is existing at the larger population level. The required minimum sample size is decided to be the most minute positive integer value that fulfills the proposed equation as per the propositions of this technique. In an Excel sheet, the estimation can be done utilizing the function ROUNDUP ((2.486/bmin) ^2, 0), wherein bmin denotes the nomenclature of the cell of excel that possess the exact value of |β|min. It is generally suggested to the PLS-SEM practitioners who do not identify themselves as very good estimators, that they should employ the inverse square root technique for estimating the required minimum sample size. It has the ability to produce more appropriate estimates from normal and non- normal data frameworks. Using this method, the produced estimations would be slightly higher than the expected true required minimum sample sizes (Kock & Hadaya, 2018; Seema & Sachdeva, 2020). So, the estimated minimum sample size as per this technique for the present investigation comes out to be 59. This estimation also congregates with one other minimum sample adequacy suggestion (Westland, 2010).

Hence, the data collected from the sample subjects in this study i.e. 161 is fairly higher than the minimum sample size estimation of all the above described and contemporary techniques used by PLS-SEM researchers. The data has been aggregated through face to face interactions with IT professionals at their suitable timings after getting preceding appointments from them. Purposive sampling was utilized to scrutinize all the target subjects and data was collected from them who were specifically interested to voluntarily talk on the research topic. The whole dataset possessed no absent values.

4.3Data analysisPartial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis with SmartPLS3.0 software is used in order to analyze the researcher’s hypothetical model. In order to run the structural equation modeling (SEM), double stage analytical procedures are recommended by the experts, which should include both the testing of the outer measurement model and the examination of inner structural model. In the present study, the outer measurement model is composed of three reflective latent variables. PLS has been accepted as a well established tool to calculate absolute path-coefficients in a variety of research models including organizational behavior studies. This has been formulated and tested by the contemporary researchers as it possesses exclusive potential to sculpt latent constructs underlying a vast variety of conditions including non-normality in data and short sample sizes ranging from small to medium (Hair et al., 2013).

5Results & discussionThe sequence of results in this section moves from the discussion of measurement model towards structural model, heading towards mediation analysis and, finally presentation of the bootstrapped model for hypothesis testing.

5.1Measurement modelThere are two types of constructs used in PLS-SEM: Reflective and formative depending upon their measurement perspective, which is guided by the construct’s conceptualization and the research objectives (Hair et al., 2013). In this study, reflective measurement model is used. Reflective model requires all the latent constructs of the study to be reflective in nature. In order to assess reflective measurement model, reliability and validity testing needs to be performed to ensure its appropriateness for investigations through PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2011).

Firstly, the outer measurement model is evaluated for examining the convergent validity of all the instruments. This is evaluated through the following three parameters: ‘Factor loadings’, ‘Composite Reliability’ (CR), and ‘Average Variance Extracted’ (AVE).

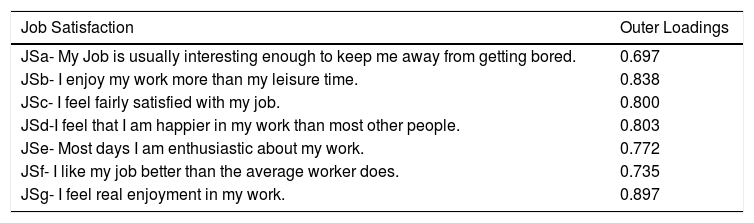

So, the ‘factor loadings’ of all three reflective constructs are analyzed as the foremost step in evaluating the measurement model. In the initial factor loadings of the standardized scales, some items were showing very less values, hence they were removed as all the three standardized scales were reflective in nature and it improves the outer model if we remove a few items from a reflective construct, who show very low loadings (Hair et al., 2013). The removal of items is permitted in reflective scales as all the items in these constructs are taking responses about one concept only through a number of similar statements. After removal of low outer loadings for refining the measurements of constructs in the outer model, the structural equation modeling is run once again. Now all the loadings reached close to or even greater than the recommended cut off value of 0.7, to be eligible of constituting a good outer measurement model (Chin et al., 2008 & Hair et al., 2013). Therefore, after examining all the outer loadings, the authors reach to the judgment that it may be considered as a moderately good outer model as seen in Table 1.

Outer Loadings of the Three Reflective Constructs.

| Job Satisfaction | Outer loadings | Organizational Commitment | Outer Loadings | Moonlighting Intentions | Outer Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSa | 0.697 | OCa | 0.766 | MLa | 0.785 |

| JSb | 0.838 | OCb | 0.715 | MLb | 0.657 |

| JSc | 0.8 | OCc | 0.891 | MLc | 0.784 |

| JSd | 0.803 | OCd | 0.635 | MLd | 0.894 |

| JSe | 0.772 | MLe | 0.775 | ||

| JSf | 0.735 | MLf | 0.877 | ||

| JSg | 0.897 | MLg | 0.556 |

Source: Data Processed.

The following tables (Tables 1.1–1.3) show the specific items adapted from the original instruments and their outer loadings estimated in the outer measurement model through PLS-SEM.

Items Adapted from Job Satisfaction Scale.

| Job Satisfaction | Outer Loadings |

|---|---|

| JSa- My Job is usually interesting enough to keep me away from getting bored. | 0.697 |

| JSb- I enjoy my work more than my leisure time. | 0.838 |

| JSc- I feel fairly satisfied with my job. | 0.800 |

| JSd-I feel that I am happier in my work than most other people. | 0.803 |

| JSe- Most days I am enthusiastic about my work. | 0.772 |

| JSf- I like my job better than the average worker does. | 0.735 |

| JSg- I feel real enjoyment in my work. | 0.897 |

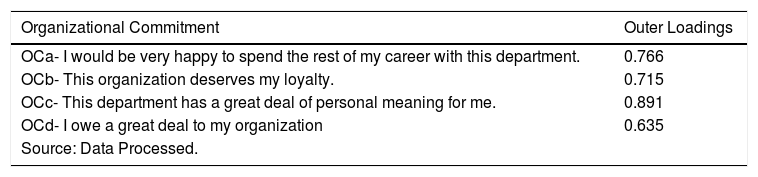

Items Adapted from Organizational Commitment Scale.

| Organizational Commitment | Outer Loadings |

|---|---|

| OCa- I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this department. | 0.766 |

| OCb- This organization deserves my loyalty. | 0.715 |

| OCc- This department has a great deal of personal meaning for me. | 0.891 |

| OCd- I owe a great deal to my organization | 0.635 |

| Source: Data Processed. |

Items of Moonlighting Intentions Scale.

| Moonlighting Intentions | Outer Loadings |

|---|---|

| MLa- How often have you considered having a second job apart from your regular occupation (Never to Always)? | 0.785 |

| MLb- How frequently do you scan newspapers/employment websites in search of part time job opportunities? | 0.657 |

| MLc- How often do you dream about getting another job with your primary job, which would collectively suit your personal needs? | 0.784 |

| MLd- How likely you would accept another job along with primary job at a desired compensation level, should it be offered to you? | 0.894 |

| MLe- How often you consider pursuing your hobby/passion other than the professional career to make extra money? | 0.775 |

| MLf- How often you think of taking another job with high growth? | 0.877 |

| MLg- Have you ever registered on online platforms for taking up second jobs along with your present job? | 0.556 |

Source: Data Processed.

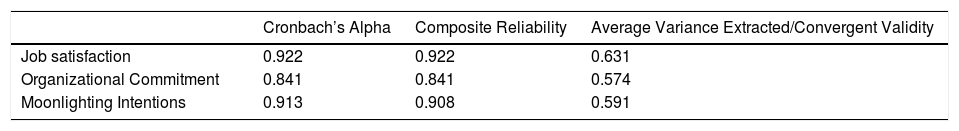

After assessing outer loadings of all the constructs of the study, next step is to assess Composite Reliability (CR) and convergent validity through average variance extracted (AVE). The composite reliability (CR) is referred to the degree of reflection of latent construct by the indicators/items of that construct. In this case, the values of CR of all three constructs surpassed the suggested value i.e. 0.5 (Hair et al., 2013). This recommendation is quite useful to distinguish and identify reliable constructs in a study. Here, all the three constructs used in our study are found reliable enough to carry on research utilizing them (Table 2). Also, all three constructs have shown AVE values greater than the recommended value of 0.5 (Hair et al., 2013).

Table 2 below shows the construct reliability, validity and AVE values:

After ascertaining the reliability and AVE values, the subsequent examination is to be done of the discriminant validity of the same outer measurement model. Discriminant validity can be referred to as the quantity of dissimilarity among all the latent constructs to be used in the study so that they can be intended to evaluate distinct measures by different scales or instruments.

The basic principle underlying the discriminant validity is that every latent construct must allocate more amount of variance with its own items rather than with other latent constructs under study (Hair et al., 2013). It can be evaluated by the less degree of correlation among the different scales of the study (Table 3). This is evident from Table 3 that the discriminant validity among the constructs in the present study is appropriate for considering the model for structural assessment or inner model evaluation.

5.2Structural modelStructural model is the inner composition of the relations among different constructs of a study.

For evaluating it, the coefficient of determination and the path coefficients, also called β or beta, are to be assessed. When the investigator is ensured of both the values exceeding the recommended ones, one can proceed for the estimation of analogous t-values by performing bootstrapping of the inner structural model with a resample of at least 500 generally (Hair et al., 2013).

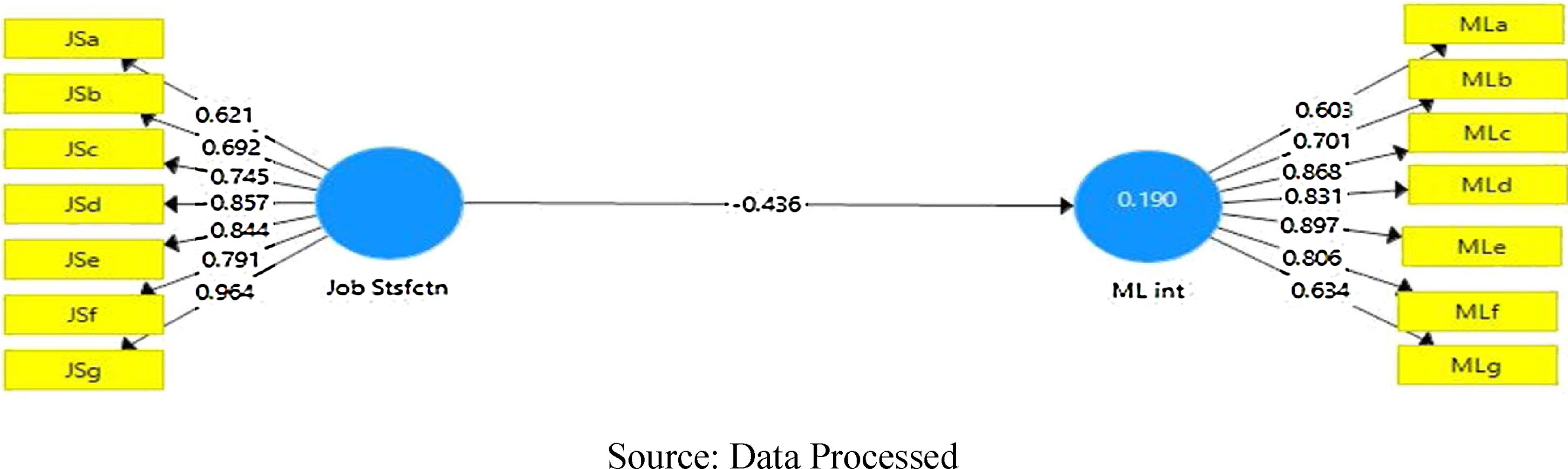

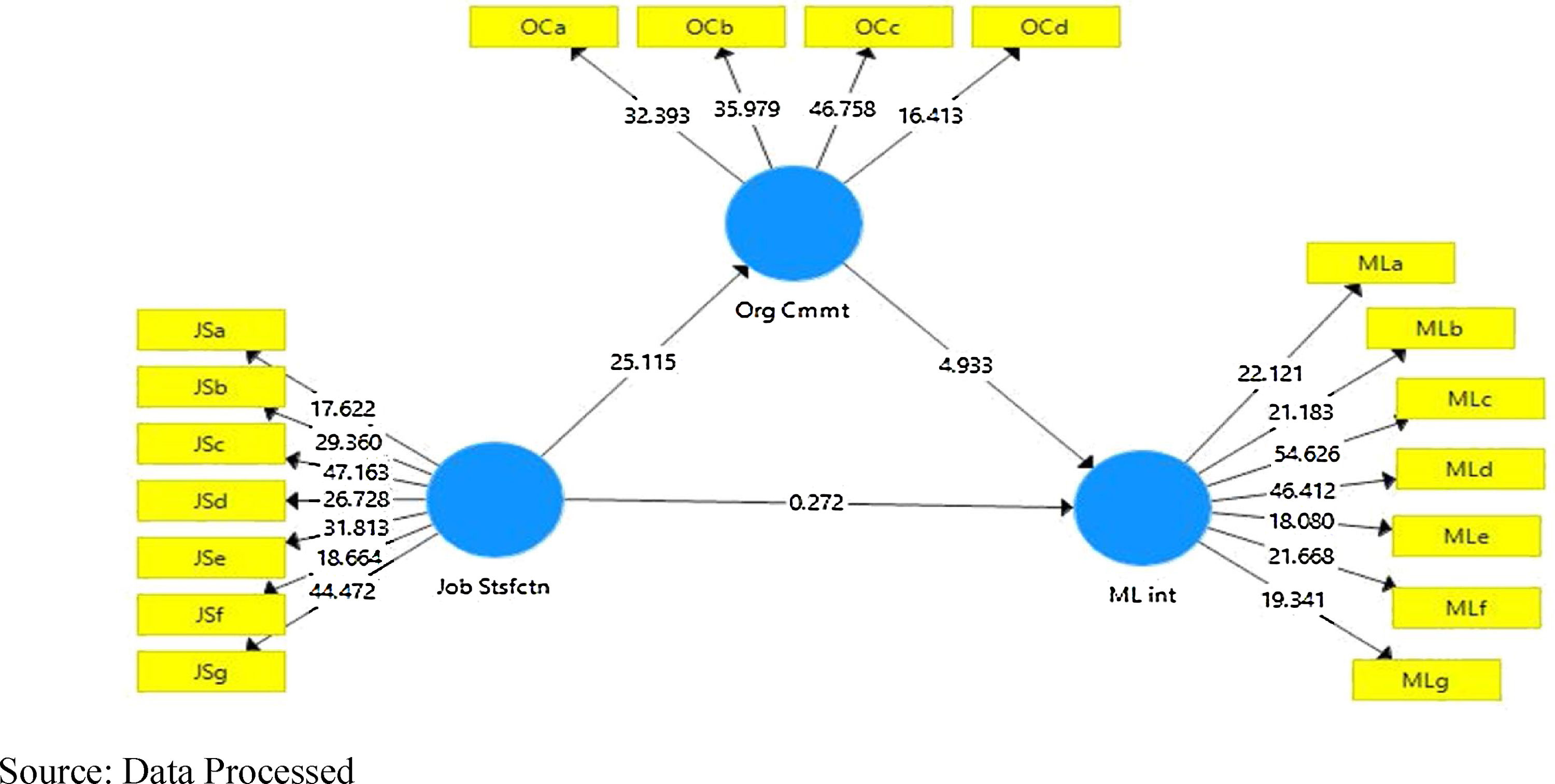

First, the associations between all the latent constructs should be ascertained. Fig. 2 depicts the structural model developed after execution of structural equation modeling in smart PLS 3.0 software. But before discussing the path coefficients in the structural model, one must examine the factor loadings once again to ensure process consistency.

As mentioned in the measurement model assessment, ‘item or factor loadings’ of all three constructs reached close to or even much greater in most cases than the recommended average cut off value of 0.7, to be eligible of constituting a fairly good outer measurement model (Chin et al., 2008 & Hair et al., 2013). Next move is to discuss those three loadings, which are less than 0.7 in the structural model depicted in Fig. 2. First is JSa with 0.697, which rounds off to 0.7 so it poses absolutely no issues. Second is OCd with 0.635 and the third is MLg with 0.556. The reason behind keeping these items in the structural model is the next recommendation of structural model assessment apart from item loading values, i.e. average variance extracted (AVE) of every construct should be greater than 0.5 (Hair et al., 2013). This AVE recommendation refers to an important perspective of outer model assessment that all the loadings of a construct should be on an average 0.7 to extend a minimum value of 0.5 AVE, to that construct (Hair et al., 2013). All the three constructs of present study fulfill this criteria of AVE as depicted in Table 2 so both these items(OCd : 0.635 and MLg: 0.556) have been retained in the structural model.

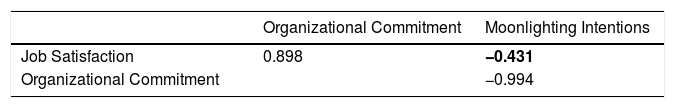

Now, while examining the path coefficients in this model in Fig. 2, one can see that Job satisfaction is considerably and positively influencing the Organizational commitment (β1 = 0.898; p < 0.05) and it is explaining 80.7% of variance in Organizational Commitment (0.807). This statistical evidence hereby suffices to support the Hypothesis H1.

Organizational Commitment is also very significantly and negatively influencing Moonlighting Intentions as it is having β2 = −0.994; p < 0.05. A very strong negative relation depicts the inversely proportional relationship between Organizational Commitment and Moonlighting Intentions, which means on increase of one, the second decreases proportionately. This figure of β2 approves the evidence for supporting Hypothesis H2.

Further, Job Satisfaction is significantly influencing Moonlighting Intentions (β3 = 0.462; p < 0.05) and these both variables (Job Satisfaction & Organizational Commitment) collectively explain 37.7% variance in Moonlighting Intentions (= 0.380). This statistical value of β3 extends support to the approval of Hypothesis H3.

This implies that the hypothetical model made by the researchers is following sufficient empirical and statistical evidences of path coefficients and coefficients of determination. Both the values of coefficients of determination (0.807, 0.377) exceed 0.26 cut off value (as suggested by Cohen, 1992), and indicate a substantial model. So, it can be adjudged as a good structural model.

5.3Mediation analysisFor testing mediation effect in PLS-SEM, the researchers need to first comprehend the significance of examining mediation effects. The basic assumption of analyzing mediation is its sequence of associating relationships wherein one antecedent exogenous construct influences a mediating construct, which in turn influences the endogenous construct of the study (Nitzl et al., 2016). This reflects the mechanism about how an investigator could elaborate the system of one construct influencing another one in research (MacKinnon et al., 2007). The comprehension of mediation related research questions is critical in management research to gain understanding about the success or failure drivers of certain processes or factors (Cepeda & Vera, 2007; Castro & Roldán, 2013 & Nitzl et al., 2016). There always exists a procedural challenge in mediation analysis of practically including an intermediating construct in the association of two constructs in a research study (Nitzl et al., 2016).

The procedural challenges of examining mediating effects has given birth to a variety of techniques which themselves have become a research topic for selecting the appropriate way of doing mediation analysis (Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Rucker et al., 2011; Hayes & Scharkow, 2013). One of the example includes the various evidences of misapplication of Baron and Kenny’s (1986) causal-steps approach performed through the multiple regression analysis, in strategic management studies (Zhao et al., 2010; Aguinis et al., 2017; Nitzl et al., 2016).

So, in order to keep pace with the latest approaches, the researchers in the present study pursue the three step approach (Shrout & Bolger, 2002; Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Zhao et al., 2010; Nitzl et al., 2016, Hair et al., 2016, Mahfud et al., 2020) which include:

First step encloses the checking of direct effect of independent construct on dependent one in the absence of mediator. If found significant, checking the significance of indirect relationship to gather all possibilities to test mediation. When direct effect not found significant, no mediating effect is estimated. If the researchers want to check the possibility of mediating relationships where evidences of direct relationships (not effects) in the existing literature are absent, bootstrapping procedure of estimating confidence intervals is the most appropriate technique (Cheung & Lau, 2008; Mahfud et al., 2020).

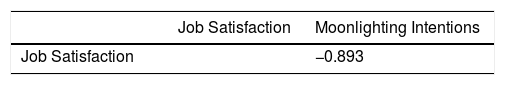

Looking at Fig. 3, it can be stated that in the absence of mediator, Job satisfaction has a negative and considerable impact on Moonlighting Intentions with the figure of 43.6 % in negative. This implies that when one increases, the other may decrease significantly. A significant direct effect of endogenous construct on the exogenous construct is evident in order to proceed for the second step.

Second step includes (when direct effect found significant) checking the strength of the indirect effect and total effect which help in ascertaining the size of the mediating effect. The size of the mediating effect is computed as VAF (variance accounted for) Ratio which is the ratio of indirect effect to the total effect (Hair et al., 2013).

The strength of indirect effect is calculated by the multiplication of mediator path coefficients of the structural model i.e. by (β1 * β2) or (0.898*−0.994) which comes out to be −0.893 which can be considered as a quite high strength. It is also evident from the same software results in Table 4.

Moreover, the value of total effect needs to be figured out for calculation of VAF (Albers, 2010; Hair et al., 2013). The total effect of Job satisfaction on Moonlighting intentions has been calculated and can also be ascertained by the software results as in Table 5.

Henceforth, division of Indirect Effect/Total Effects (Hair et al., 2013) calculates VAF and in the present study as −0.893/−0.436 which comes out to be 2.048. This value of VAF depicts a high mediation, which is examined in the third step.

So, VAF of present Study = Indirect Effect/ Total Effects = −0.893/−0.436 = 2.048

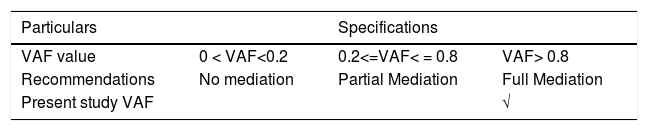

Third step includes assessing the type of mediation (Full, partial or No Mediation). Referring to the following recommendations by Hair, et al. (2013) for adjudging the type of mediation:

According to Table 6, it is concluded that organizational commitment fully mediates the relationship between job satisfaction and moonlighting intentions as hypothesized in the H4.

Assessment of Mediation Extent.

| Particulars | Specifications | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VAF value | 0 < VAF<0.2 | 0.2<=VAF< = 0.8 | VAF> 0.8 |

| Recommendations | No mediation | Partial Mediation | Full Mediation |

| Present study VAF | √ |

(Source: Assessment of mediation through VAF value. Adapted from A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (p. 224), by Hair Jr et al. (2013), Sage Publications).

Hence, H4 hypothesis is supported in the light of above discussed statistical evidence of mediating effect.

These three comprehensive steps of testing mediating effect between two latent constructs have been proposed by most of the contemporary researchers in PLS-SEM (Shrout & Bolger, 2002; Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Zhao et al., 2010; Nitzl et al., 2016, Hair et al., 2016, Mahfud et al., 2020).

5.4Bootstrapped modelBootstrapping is a procedure wherein a sufficiently high number of data sub-sets are randomly drawn from the original sample of research data, with replacement, in order to perform non-parametric inference and modeling (Nitzl et al., 2016). In order to perform hypothesis testing for the structural model, bootstrapping through a resample of at least 500 should be executed to retrieve t-statistical values. In addition, a solitary criterion suggesting the goodness of fit in estimating any PLS-SEM model is not available, so bootstrapping may be used as one of the effective approaches (Hair et al., 2013).

The Bootstrapped model (Fig. 4) also suggests a considerably strong association allying job satisfaction & organizational commitment and an inverse alliance of organizational commitment & moonlighting intentions with considerable values of t-statistics as 25.115, 4.993 and 0.272 respectively. Further, the effect sizes are to be assessed by F square values. The values smaller than 0.02 propose small effects, 0.02 to 0.15 reflect medium effect and 0.15 to 0.35 and greater values imply large effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). Therefore, it is evident in Table 7 that H1 has a large effect size, H2 also has large and H3 has medium effect size.

Estimates of Structural Equation Modeling (Hypothesis testing).

| Hypotheses of Study | Beta/ Path Coefficient | t- statistics | Decision | F^2 | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: JS→ OC | 0.898 | 25.115 | Supported | 4.186 | Large |

| H2: OC→MI | −0.994 | 4.993 | Supported | 0.306 | Large |

| H3: JS→MI | 0.462 | 0.272 | Supported | 0.066 | Medium |

| H4: OC mediates JS & MI | Tables 4,5,6 | NA | Supported | NA | Full Mediation |

(Note: Critical t-values for p < 0.05).

Source: Data Processed.

Thus, the results report both the substantive significance () and statistical significance (p) jointly for better understanding of statistical figures by the researchers at large because p value provides only for the significance of associations and no clue can be found about their absolute effect sizes from this value.

6ConclusionsThe relationships of job attitudes with withdrawal cognitions of the employees leading to turnover have been studied since the March and Simon (1958) turnover model and the relationship between moonlighting (a withdrawal cognition) and turnover also captures a significant share of literature. But the empirical evidences of job attitudes (specifically job satisfaction and organizational commitment) with moonlighting is found meager and calls for focused investigations in the light of virtual work-arrangements enabling online moonlighting and platform working in the industry 4.0.

Even though modern organizational science researchers have been studying moonlighting intentions of IT professionals keeping in mind their much discussed pecuniary motives and demographic characteristics, the present study may be a significant attempt to understand the other two non-pecuniary triggers of moonlighting intentions’ in an empirical approach. Four Hypotheses have been tested in this study for estimating all the associations between the three latent constructs job satisfaction, organizational commitment and moonlighting intentions of I.T. professionals of selected organizations of India. It can be concluded that PLS –SEM supported all of them. In addition, it can be inferred that organizational commitment poses a full mediating effect between job satisfaction & moonlighting intentions while job satisfaction reflects a very high positive influence on the construct organizational commitment that in turn shows a much considerable inversely proportionate relationship with moonlighting intentions. These conclusions draw the attention of the strategy builders of the organizations towards a rising behavioral correlate of the workforce i.e., intention to moonlight in absence of appropriate measures or antecedents to increase job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The same is evident in both the literature review and the findings of the present study. The negative associations in the findings point towards the inversely proportional relationships. Also, during the current pandemic time, workforce is bound to look for alternative mechanisms of generating secondary sources of income to secure their livelihoods through paid microworks or mini gigs in case of sudden lay-off, so moonlighting through platform working during the frequent lockdowns is being seen as an amusing economic safety cushion by the tech savvy I.T. professionals.

7Limitations and recommendationsThis study has been conducted after collecting data from a limited sample of I.T. professionals, so the results must be carefully comprehended before generalizing to the larger population. Also, other workplace and behavioral correlates along with the inclusion of higher effects like multiple mediations and moderation; can be taken up for better comprehension of the moonlighting intentions of the employees.

With the advent of Industry 4.0 and the predictions about the evolving work arrangements post covid-19, wherein gig working, online e lancing, crowd-work and virtual work arrangements would be the new normal, it is suggested that any organization should not simply ban the moonlighting practices of its workforce without looking for its various impacts on the organization and the society at large, some of which may be noted as follows. First impact would be on the organizational branding by banning gig working for knowledge workers as various reputed players like Microsoft are already facilitating it. This ban would also lead to higher costs of training and development as platform working keeps the workforce at pace with the technological advancements. Second impact may happen to other organizational cost factors for not engaging gig workers for the repetitive or microworks and not seeking specialized services from crowd for benchmarking quality standards. Third may be the revenue losses by forbidding the employees to do gigs thereby triggering their turnover intentions and ultimately facing their attrition. So, HRM functions in collaboration with the organizational management need to re-engineer their work practices accordingly so that a beneficial state of affairs can be created for both the management and workforce. The situations like this are paving the path towards new occupations in the HR functions, which never existed in the organograms in the previous decades like Gig work Strategist, and future of work manager etc., as mentioned earlier. This is how the future of work can be facilitated for enabling successful businesses in the upcoming virtual industries.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors express their sincere gratitude to all the respondents of the study for sparing their valuable time and honestly responding to the questionnaire which helped immensely in guiding this study. Our genuine gratefulness extended to Mr Kewal Krishan and Mr Ajay Bansal for their end to end support in the data collection process and Prof. Suruchi Kalra for extending impeccable editing support in drafting the present version of this paper.