The purpose of this study is to examine various configurations leading to job satisfaction (JS) in Mongolian private companies through five typical factors: perceived mission statement quality (MSQ), romanticism management philosophy (RMP), psychological ethical climate (PEC), ethical ambiguity (EA), and emotional competence (EC).

MethodThis study conducts a fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) with 202 private sector employees in Mongolia. The current study comes up with three propositions, and the research procedure is divided into two stages. This new approach produces configurations sufficiently, leading to outcomes, equifinality, and conjunction.

FindingsThis study explores six pathways leading to employee satisfaction. Each pathway consists of the combination of perceived mission statement quality, romanticism management philosophy, psychological ethical climate, low tendency of ethical ambiguity, and managers’ emotional competence. Among those, managers’ emotional competence is a core condition for high job satisfaction.

ImplicationsOur findings suggest that to satisfy employees, managers’ emotional competence plays a vital role in building sufficient conditions that lead to the desired outcomes. Thus, professional development and training are required to maintain and improve managers’ competence.

Originality/valueThis study introduces a fresh theoretical perspective for understanding cause-effect relationships between critical conditions and job satisfaction.

The importance of employee satisfaction as one of the essential factors helping businesses maintain their competitive advantage and assist companies in overcoming the marketplace's challenges (Alegre et al., 2016; Bourini et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2019). It is widely accepted that satisfied employees act as good brand ambassadors for businesses that can elevate work efficiency (Robertson & Cooper, 2011). Researchers have shown that employees’ loyalty and commitment always come from satisfaction (Goujani et al., 2019; Schwepker, 2017). Therefore, it is highly essential to focus on human resources and createe job satisfaction (Christen et al., 2006; Eliyana & Ma'arif, 2019).

Due to the importance of job satisfaction, several studies have been conducted to determine the best ways for managers to build and maintain employee satisfaction (Brunetto et al., 2012; Schwepker, 2017; Schwepker & Schultz, 2015; Wang & Hsieh, 2012). Existing studies mostly rely on organizational or employee standpoints explaining the typical factors that cause employee satisfaction are quite numerous and different (Kim & Miller, 2008; Marques-Quinteiro et al., 2019). However, job satisfaction is a complex concept that includes many causes, which may arise from the company, employees’ personalities, or the external environment. Therefore, employee satisfaction is driven by multiple causes instead of a single cause. Although early works from different fields such as human resource management and organizational behavior devote remarkable efforts to identify and assess the antecedents and consequences of job satisfaction, provided perspectives usually rely on individual interactions between research constructs (Macintosh & Krush, 2014; Schwepker, 2017; Schwepker & Schultz, 2015) without considering other key determinants that simultaneously can influence job satisfaction. The current study's motivation is to fill the gap by investigating and analyzing the causal complexity perspective of combining elements that persuade employees’ job satisfaction, particularly in Mongolia.

This study has the same expectations as many previous studies to improve managers’ knowledge of conditions affecting employee satisfaction, enabling leaders to make appropriate decisions. Thus, a unique set of factors never studied before is considered to analyze job satisfaction's causal complexity. As a result, five prevalent agents are crucial for profitability and productivity including perceived mission statement quality (Desmidt, 2016), romanticism management philosophy (Joullie, 2016), psychological ethical climate (Victor & Cullen, 1987), low ethical ambiguity (Boyatzis & Sala, 2004) and emotional competence (Meyer & Allen, 1991). In general, previous studies successfully develop job satisfaction models with significant practical results. According to those frameworks, managers can make appropriate adjustments to build, improve, or sustain employee satisfaction. While most of the previous studies have mainly provided single alternatives for different contexts, this paper conducts a different methodological approach that is called fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA), which provides a more logical result when analyzing the interactions among multiple variables.

Consequently, we select five crucial determinants of job satisfaction, including mission statement quality, romanticism management philosophy, psychological ethical climate, low ethical ambiguity, and emotional competence.

FsQCA is an appropriate tool that allows researchers to adopt a configurational approach and tests the causal complexity analysis among job satisfaction antecedents (Fiss, 2007; Frazier et al., 2016; Ham et al., 2019; Kosmidou & Ahuja, 2019; Ragin, 2008a). This methodology helps build, develop, or enhance employee satisfaction (Berg-Schlosser et al., 2009). Thus, research content enriches the literature by using a novel method in the management context, fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA), to address the common vital factors that lead to employee's job satisfaction while identifying the importance of other elements in each of the different options. Finally, the paper attempts to bring a new approach to employee satisfaction and become a pioneering document for researchers and managers in the private sector.

2Theoretical background and research propositionsThis section discusses the concept and theories related to job satisfaction. In addition, under the scope of organizational climate, five conditions leading to employee job satisfaction are explained.

2.1Job satisfaction (JS)Hoppock (1935), one of the earliest scholars, defines job satisfaction as employees’ psychological and physiological satisfaction towards the working environment and the job itself, reflecting a subjective reaction to a work situation. Later, Locke (1969) determines job satisfaction as “the pleasurable emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one's job as achieving or facilitating the achievement of one's job values.” Job satisfaction may be both intrinsic, which is derived from internally mediated rewards such as the job itself, opportunities for personal growth, and accomplishment, or extrinsic that is resulting from externally mediated rewards such as satisfaction with payments, company policies and supports, supervision, fellow workers, chances for promotion, and customers (Eliyana & Ma'arif, 2019; Walker et al., 1977; Yazhou & Jian, 2011).

Consequently, items that contribute to promoting job satisfaction come from different internal and external factors (Jung, 2019; Moslehpour et al., 2019; Smilansky, 1984). Notably, most previous studies are found limited to consider linear or simple structural effects, while causal complexity perspectives that lead to job satisfaction are ignored (Bakotić, 2016; Judge et al., 2017). Therefore, to address this research gap, the present paper uses fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to create configurations of employee satisfaction, which allows combining many conditions simultaneously (Gabriel et al., 2018). It is hard for businesses to consider all the elements involved in employee job satisfaction. Thus, solutions of configurations may work well for different business circumstances (Kampkötter, 2017).

2.2Organizational factors of employee job satisfactionWe utilize a group of organizational factors, including mission statement, management philosophy, ethical climate, ethical ambiguity, and emotional competence, which lead to employee job satisfaction. The reason to choose selected constructs is that all mentioned factors often do not affect job satisfaction linearly, but these determinants are crucial to generate satisfaction in the long-term when other factors such as salary and bonus are present (Gabriel et al., 2018; Kampkötter, 2017). In the next sections, the authors present the conditions that boost employee satisfaction based on the five selected factors.

2.2.1Perceived mission statement quality (MSQ)A mission statement is essential for an organization's survival and development because it guides the action towards better decision-making. A mission statement plays an incentive role for the organization's members (Alegre et al., 2018; David, 1989; Kemp & Dwyer, 2003). It is acknowledged that the mission statement is one of the leading factors and has a decisive role in subordinates’ effectiveness when working under directions (Braun et al., 2012; Rey & Bastons, 2018). The relationship between perceived mission quality (MSQ) and job satisfaction (JS) is explored in other contexts and with a different population. Aydin et al. (2013) pilot a meta-analysis related to the influences of Turkish school administrators’ MSQ and JS. The outcomes indicate a statistically significant relationship between the two constructs. Aydin et al. (2013) recommend that all employees be educated and trained on school missions, actions and decision-making processes to increase teachers’ levels of job satisfaction and organizational pledge. A study of 1,418 Belgian employees from a public welfare organization suggests that there could be a strong connection between MSQ and JS (Desmidt, 2016). Asrar-ul-Haq et al., (2017) study of 245 Pakistani higher education employees indicates that social responsibility significantly influences job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

However, the mission statement is not always understood fully and effectively by employees, especially when the statement only reaches those considered essential, such as customers, shareholders, and suppliers (Alegre et al., 2018; Nassehifar & Pourhosseini, 2008). For this reason, limited numbers of studies have shown the impact of employees’ perceived mission statement quality on job satisfaction. Therefore, this study attempts to be one of the primary studies that discuss the relationship between employee‑centered mission statements and job satisfaction.

2.2.2Romanticism management philosophy (RMP)Romanticism emphasizes intrinsic motivations as useful instruments to improve creativity and innovative performance (Amabile, 1997; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Hennessey & Amabile, 1998). This approach considers HRM practices, including reward management, to facilitate employee self‐motivation as beneficial for innovative behavior (Collinson et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Many non-monetary rewards and development-oriented human resource treatments have been tested for their effectiveness at enhancing creativity based on the power of intrinsic motivations (Feng et al., 2018). Previous works in different context include actively building encouragement and recognizing innovative organizational atmosphere (Baer & Frese, 2003), enriching job responsibility and empowerment (Oldham & Cummings, 1996; Tierney & Farmer, 2004), setting modest challenges and innovative performance targets in tasks (Shalley, 1995), implementing improvement and guidance-oriented performance communication and feedback (Zhou, 1998), providing training resources and comprehensive learning opportunities (Shipton et al., 2006), planning career development with job rotation and multiple channels (Gupta & Singhal, 1993), and maintaining good interpersonal relationships among employees (Ruppel & Harrington, 2000). In general, intrinsic motivations are seen as a positive source of promoting innovative behaviors (Rockmann & Ballinger, 2017). The romanticism management philosophy is also an essential factor in elevating employees’ motivation that eventually creates long-term satisfaction at work (Collinson et al., 2018). Thus, this research considers RMP as a second condition to reflect employee satisfaction.

2.2.3Psychological ethical climate (PEC)Psychological ethical climate refers to the ethical atmosphere experienced by an individual employee (Wang & Hsieh, 2012), and it also refers to perceptions of the ethical rules, policies, values and behaviors in the work environment (Hsieh & Wang, 2016; Victor & Cullen, 1987). Numerous previous studies focus on the enforcement of ethical codes, ethical policies, and punishment as means to define and measure ethical climate (Schwepker, 2001; Weeks et al., 2004). The ethical climate is arguably the most manageable factor the organization can use to influence ethical behaviors (Schwepker et al., 1997). Ethical behavior and values are expected when encouraged and supported by the organization (Wimbush & Shepard, 1994). However, unethical behavior is anticipated in climates that ethical standards and values are not transparent (Peterson, 2002). A considerable number of studies show the positive relationships between psychological ethical climate and job satisfaction (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2013; Schwepker 2001; Teresi et al., 2019 ;Valentine et al., 2011). A literature review reveals that when employees have a positive perception of the company's ethical climate, they are more willing to work and try harder. Thus, it is sensible to select psychological ethical climate as the third condition leading to job satisfaction in this study.

2.2.4Ethical ambiguity (EA)Ethical ambiguity refers to the uncertainty of handling ethical situations arising on the job (Singh & Rhoads, 1991). In other words, ethical ambiguity is the degree of uncertainty an employee experiences on how to behave in the day-to-day performances, and then it becomes a sign of non-clarity on ethical expectations (Robertson & Rymon, 2001; Singh & Rhoads, 1991) that occurs both internally and externally to the organization (Rhoads et al., 1994), ethical ambiguity might negatively affect job satisfaction. In line with this, many studies address that ethical ambiguity is one of the leading causes of stress when employees feel helpless or fearful of the consequences of their uncertain actions. Thereby, ethical ambiguity might considerably affect the working interest and create stagnation at work in the long run (Boyatzis & Sala, 2004; Maden-Eyiusta, 2019; Schwepker, 2017). As a result, effective leadership is significantly helpful for employees to reduce ambiguity (Schwepker & Hartline 2005). Hence, ethical ambiguity has a definite association with job satisfaction, especially jobs with unclear boundaries such as sales, accounting, customer service staff and several others.

2.2.5Emotional competence (EC)Emotional competence is often used to describe an individual emotional intelligence, which comprises identifying, understanding, regulating, and utilizing emotions about self and others (Fiorilli et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2001; Sung et al., 2020;Wong & Law, 2002). As such, individuals with high emotional competence often have a good relationship with others outside the workplace. In other words, having the ability to imagine themselves in others’ situations enables people to win the hearts of those around them (Kim et al., 2009). For this reason, emotional competence is an indispensable factor not only to predict employee performance but also to evaluate job satisfaction. Many scholars argue that having a high level of emotional competence allows employees to adapt to job changes, proactively minimize stress quickly, and more importantly, realize how to overcome adverse changes in emotions (Giardini & Frese, 2008; Mayer et al., 2000). As a result, these employees express a higher level of job satisfaction that enables them to bring more positive energy to work (Barsade & Gibson, 2007).

2.3Research propositionsFollowing the above literature review and the arguments mentioned, the authors discuss those conditions to develop the research propositions.

Firstly, we review the roles of perceived mission statement quality, romanticism management philosophy, ethical climate, and ethical ambiguity. Campbell (1992) mentions that the mission statement is an important management tool in defining an organizational culture that is attractive to employees, potentially affecting employee recruitment, satisfaction, motivation, and retention. Other researchers consider that organizational attitudes are influenced by mission attachment, a suite of factors that includes employee awareness, agreement, and alignment with the mission (Kim & Lee, 2007; Yazhou & Jian, 2011). Moreover, they further argue that mission attachment is a reliable predictor of job satisfaction. In parallel with the mission statement, romanticism management philosophy is another significant antecedent when emphasizing intrinsic motivations as useful instruments to improve creativity and innovative performance that, in return, can enhance job satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Hennessey & Amabile, 1998). In line with organizational mission and romanticism, ethical climate (EC) is also likely to associate with their job satisfaction (Koh & Boo, 2001; Tsai & Huang, 2008; Elçi & Alpkan, 2009). However, the concept of ethics in business is often ambiguous. Previous research has shown that ethical ambiguity negatively affects job satisfaction. As a result, employees who experience the ambiguity of ethical issues often face the stress that translates into lower levels of job satisfaction (Rhoads et al., 1994). Considering that emotional competence is found to know, manage, and regulate uncertain emotions of oneself and others, high emotional competence staff can deal with ethical ambiguity in the workplace (Boal & Hooijberg, 2000; Sternberg, 1997). Thus, emotional intelligence is proposed as a significant predictor of job satisfaction (Carmeli, 2003; Daus & Ashkanasy, 2005; Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, 2004; Sy et al., 2006). Therefore, we maintain that the five discussed factors are among the most critical conditions that create employee satisfaction. Furthermore, they create various configurations to determine the extent of influence when combined in a model. For this reason, we come up with the first proposition:

Proposition 1 Perceived mission statement quality, romanticism management philosophy, psychological ethical climate, low ethical ambiguity, and emotional competence can form multiple configurations for the occurrence of high job satisfaction.

Secondly, we discuss the leading role of emotional competence in job satisfaction. Feelings of competence are essential for intrinsic motivation when people are responsible for their successful performance (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Similarly, based on emotional competence, leaders can influence their followers’ self-concept motivation, which influences the competitive advantage of the organization (Chipumuro et al., 2016). Therefore, in this study, the authors find a particularly important role in emotional competence in job satisfaction. As extensively mentioned by previous studies, emotional competence refers to the unique ability to effectively handle problems arising at work (Siegling et al., 2015). People with high emotional competence can self-regulate and balance at work to achieve the best state of satisfaction (Bar-On & Parker., 2000).

Similarly, if a leader has a high emotional competence, they might know how to encourage the team to work effectively, maintain motivation, and minimize stress. Nevertheless, high emotional competence becomes a necessary condition that creates motivation and happiness in work and ultimately leads to long-term job satisfaction (Augusto-Landa et al., 2011; Sung et al., 2020). Thus, the paper constructs the second proposition:

Proposition 2 Emotional competence is the most critical factor in these conditions. Leaders with emotional competence can motivate employees to have high levels of perceived competence or enhance high levels of employees’ perceived autonomy.

Finally, we discuss the roles of perceived mission statement quality and psychological ethical climate since these two factors serve the same functions. As mentioned, the organization's mission statement is an essential incentive for employees to work hard (Alegre et al., 2018; David, 1989; Weiss & Piderit, 1999). Correspondingly, mission statements make employees regularly examine and consider organizational situations and tasks. Furthermore, the mission statement is also an important management tool to create organizational culture, attract new members, and lead to job satisfaction (Campbell, 1992). In line with these points, many researchers argue that the mission statement is a good predictor of job satisfaction since an effective mission statement conveys organizational direction and motivates employees to improve job satisfaction (Huyghe & Knockaert, 2015). Prior studies show that perceptions of ethical climate are also associated with numerous positive outcomes on the effectiveness of the workplace (Mayer et al., 2009). Therefore, an ethical climate can be used to influence ethical behavior in an organization. Managers can develop and communicate codes of ethical conduct to provide direction regarding acceptable and unacceptable behavior.

Consequently, rewards and punishments are also relevant to build an ethical climate, as management can influence behavior through their administration of rewards and punishment (Posner & Schmidt 1987; Teresi et al., 2019; Trevino, 1986). Thus, it is claimed that the common points of perceived mission statement quality, as well as ethical climate, are important determinants to frame organizational culture and impact employee job satisfaction (Webber et al., 2007). Therefore, the authors state that both conditions are necessary and suitable to create job satisfaction. So, we propose the following:

Proposition 3 The presence of either a perceived mission statement or psychological ethical climate is needed to form a sufficient configuration for causing high Job satisfaction. They are something for leading employees towards organizational goals. However, they have the same function so that they can substitute for each other.

This study develops the questionnaire based on the literature review. All items of the questionnaire are measured by a Likert five-point scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree). Cronbach's Alpha for all constructs is above 0.7, reaching the criterion and indicating high levels of internal consistency (Drasgow, 1984;). In the questionnaire, the construct of perceived mission statement quality (Cronbach's Alpha =0.82) uses four items of Desmidt (2016) to measure perceived mission statement quality. Romanticism management philosophy construct (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.73) is assessed with three items developed based on Joullie (2016). Psychological ethical climate (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.74) is assessed using seven items developed by Schwepker (1997). Ethical ambiguity (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.73) is measured with four items taken from Schwepker (2017) study reflect employees’ reactions to ethical situations arising on the job. Emotional competence is measured using (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.92) 18 items originated from the 72-item emotional competency inventory (ECI-2) developed by Boyatzis and Sala (2004). Finally, job satisfaction (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.69) used the six-item measure of Korff et al. (2017). The detailed items and their means are summarized in the Appendix. Table 1 displays the mean, standard deviations, and correlation matrix for our measures.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

Based on previous studies Bellman and Zadeh, 1970; Zadeh, 1965; Zimmermann, 1985; Zimmermann, 2011, Gill et al. (1994) offer the formula ((1) in work measurement environment for sample size under fuzzy conditions.

nm = Median of required sample size

i = number of membership functions (MF) for fuzzy sampling

t = Select or average time

s = Standard deviation of the average time

z = Standard normal deviate (or z-score) corresponding to the level or degree of confidence selected.

p = Desired precision or accuracy of the estimate

Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), for the most part, has been used with N small. However, as Woodside (2012) indicates, there is no mathematical limitation that prevents this methodology from using with N large. Previous studies (Fiss, 2011; Greckhamer et al., 2008) use QCA methodology for analyzing large-N situations (more than 50 cases). Palacios-Marques et al. (2017), in their study of factors influencing innovation performance, apply fsQCA using 209 cases. Both small-N and large-N QCA studies can be used for either inductive or deductive theory testing or theory building. Large-N QCA is more suitable for theory testing studies, especially “in organization studies that hypothetico-deductive theory testing be tightly coupled with statistical testing of probabilistic criteria” (Greckhamer et al., 2013, p.56).

We collect the data from the employees of the private sectors of randomly selected companies located in Ulaanbaatar, the capital city of Mongolia, with complete anonymity. The purpose of this study is to examine various configurations leading to job satisfaction (JS) in Mongolian private companies in general. Therefore, this study did not target any specific industry or business. We identified the companies located in the capital city and contacted them in advance, and gathered a total sample size is 202 usable questionnaires. During data collection, respondents were asked not to indicate any form of identification to ensure the anonymity of their responses. Of these, 148 (73.3%) are females, and 54 (26.7%) are males. About 46% of the respondents are in the age group of 26 to 30 years, while 22.3% of the respondents are between 31 and 40 years. The majority of the respondents have a monthly salary ranging from USD 361 to USD 580 (48.5%) and from USD 581-USD 870 (30.7%).

3.2Analytic techniqueThis study employs a fuzzy-set QCA approach, an analytic technique grounded in set theory that transcends the limitations of quantitative and qualitative research (Ragin, 2008a) that allows for a detailed analysis of how causal conditions contribute to an outcome (Fiss, 2011). This approach is useful for recognizing the combinatory effects among multiple conditions and exploring different causal paths (i.e., combinations of conditions) that are sufficient for the outcome (Frazier et al., 2016; Ragin, 2008b). These alternate paths are treated as logically equivalent (Berg-Schlosser et al., 2009). By using a bibliometric method, Roig-Tierno et al. (2017) conclude that 80% of the 222 fsQCA-used articles since 2001 are published in indexed journals.

FsQCA fits this study's purpose because it helps determine the different causal models for explaining a particular phenomenon of interest rather than specify a single model that best fits the data (Berg-Schlosser et al., 2009). This approach proceeds in two major steps for empirically identifying causal recipes. First, all measures based on Likert-scale are calibrated into fuzzy-set membership scores. We specify 5, 2.99, and 1 of the interval-scale variables that correspond to three qualitative breakpoints that structure a fuzzy set: the threshold for full membership (=.95), the cross-over point (=.50), and the threshold for full no-membership (=.05). Note that emotional ambiguity has been reversed to reflect how employees are certain about their conduct when encountering ethical issues (Fiss, 2011; Frazier et al., 2016; Ragin, 2008a).

Because fsQCA technique uses Boolean algebra, it is necessary to reconstruct a raw data matrix as a truth table, which is the technical term in algebra (Ragin, 2008b). Thus, the second step is to construct a truth table, which is a tool that allows structured and focused comparisons for using Boolean algebra (Ragin, 2008a, 2008b). The truth table contains 2k rows, where k denotes the number of causal conditions (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2009), and it is equal to five in this study. Each row represents a specific combination of conditions. In this study, the full truth table lists 32 logically possible combinations of conditions and their associated outcome. Beside, the cases were sorted into the rows of the truth table according to whether they match the attributes of the combinations (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2008b).

For reducing the truth table to simplify configurations, there is a need to specify frequency threshold, which is used to assess fuzzy subset relations, and consistency threshold, which allows for assessment of the consistency of the evidence for each causal combination with the argument that it is a subset of the outcome, to edit the truth table (Ragin, 2009). Based on Ragin's (2008a, 2008b) suggestions, we set the frequency threshold at three cases and the lowest acceptable consistency for solutions at .95.

Table 2 shows the resulting truth table listing 18 configurations and 137 cases relevant to the outcome. Sixty-five cases are dropped out of the subsequent analysis because 51 are at the ambiguous position, which cannot be judged as to whether exhibiting the configurations, and 14 cases are below the consistency threshold. Among 32 configurations, six configurations lacked empirical evidence and eight ones with less-than-threshold consistency scores are insufficient for achieving the outcome. Thus, these 14 configurations are excluded from the minimization processes, but they are still considered in the counterfactual analysis.

Truth table.

Note: 0 denotes the absence, whereas 1 denotes the presence of the condition/outcome.

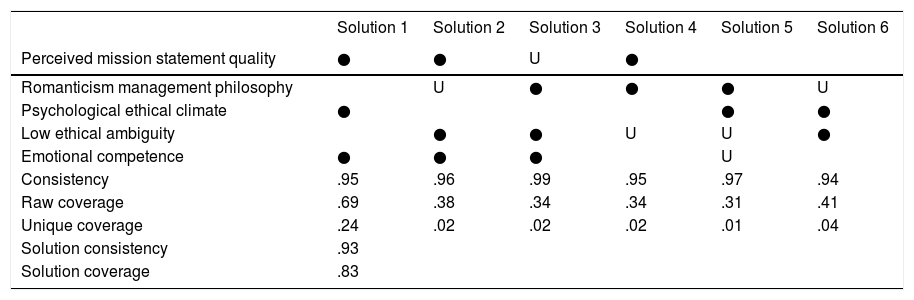

Table 3 presents the results of the fsQCA analysis of high job satisfaction. Following Ragin and Fiss (2008) suggestions, we use the notation system for presenting fsQCA's result in which black circles (●) indicate the presence of a condition, circles with a cross-out (⌔) represent the absence of a condition, and blank spaces indicate a “do not care” condition, meaning its presence or absence cannot influence the outcome in a solution. While small circles represent peripheral conditions, large circles refer to core conditions.

Configurations for achieving high job satisfaction.

Core conditions are represented by ● (presence) and ⌔ (absence); peripheral conditions by ● (presence) and ⌔ (absence). Blank cells indicate that a particular causal condition is not relevant within that solution configuration.

Table 3 shows that six solutions, exhibiting acceptable consistency (=.93) and coverage (=.83) values, are identified. Thus, these solutions indicate that perceived mission statement quality, romanticism management philosophy, psychological ethical climate, low ethical ambiguity, and emotional competence can form multiple configurations for the occurrence of high job satisfaction, which supports Proposition 1. These configurations all have high levels of consistency (.94∼.99) and raw coverage (.31∼.69), indicating that these configurations are significant causal recipes for leading to high job satisfaction and are capable of explaining a high proportion of the outcome. Beside, values of unique coverage for these solutions are all greater than zero (.01∼.24), meaning each solution has an individual contribution to explaining high job satisfaction.

Regarding core conditions, Solutions 1, 2, and 3 indicate that emotional competence, which is a core condition, combining other conditions as peripheral conditions, is sufficient for achieving high job satisfaction. This supports Proposition 2. However, the combinations of these peripheral conditions for these three solutions are different. Specifically, with emotional competence, either psychological ethical climate or low ethical ambiguity as one of the peripheral conditions is sufficient to let job satisfaction grow. Moreover, these solutions suggest that, when employees display high levels of emotional competence and low levels of ethical ambiguity, there are trade-offs between perceived mission statement quality and romanticism management philosophy.

Solution 4, 5, and 6 represent a situation in which competence is not an influential condition or a low level of competence. Comparing Solution 4 and 5 indicates that romanticism philosophy becomes a core condition when high ethical ambiguity exists. Furthermore, solutions 4, 5, and 6 all indicate that romanticism management philosophy and low ethical ambiguity can be treated as substitutes, meaning the presence of romanticism management philosophy is necessary if low ethical ambiguity is absent and vice versa. Other than Solution 3, other solutions support Proposition 3 that the presence of either perceived mission statement quality or psychological ethical climate is a peripheral condition for leading to high job satisfaction.

5Discussion and conclusionOne of the key findings suggests that no single configuration explains high job satisfaction. This study identifies six pathways leading to employee job satisfaction, and each pathway contains perceived mission statement quality, romanticism management philosophy, psychological ethical climate, low tendency of ethical ambiguity, and managers’ emotional competence. Identifying the causal process is accomplished by taking a novel analytic approach to broaden our understanding of how different aspects of the organizational environment and employee ethical ambiguity can create high job satisfaction. While prior studies contributed to the literature by exploring a relationship between these conditions and job satisfaction, we are interested in whether causal combinations are sufficient for high job satisfaction.

The first three configurations indicate that managers’ emotional competence is a core condition for high job satisfaction, lends much credence to literature (Edwards and Fisher, 2004; Kazi et al., 2013; Papathanasiou & Siati, 2014). These findings are consistent with previous studies bolding the significant role of emotional competence as a stimulus of employee's job satisfaction. Importantly, results underline that a higher level of emotional competence is greatly associated with large-scale positive changes in organizational behavior (Giardini & Frese, 2008; Mayer et al., 2000; Miao et al., 2016). The utilization of emotional competence as a manager's ability to regulate and direct emotions toward constructive performance is fundamental for successful leadership. Leaders with the more excellent capability of managing emotions are more qualified to structure a productive work environment for their employees and help them improve their emotional conditions that can enhance job satisfaction (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017).

This highlights the significant role of managers in promoting employees’ job satisfaction. These configurations also imply that the alternative of ethical climate and a low level of ethical ambiguity are necessary for creating high job satisfaction, especially when high levels of emotional competence exist. Put it simply, in the workplace; employees always evaluate managers’ competence; meanwhile, they need a clear external norm (ethical climate) or internal guide (low ethical ambiguity) to achieve high-level job satisfaction. Therefore, a manager's manner actively influences employees’ perceptions regarding the ethical climate. In return, when the ethical climate grows, ambiguity will decrease. As discussed by early works, through the leader's ethical behavior, perceived by employees, managers will directly or indirectly influence job satisfaction (Den Hartog, 2015; Schwepker & Hartline 2005). Thus, regardless of the manager's level, when interacting with other employees, emotional competence plays a critical role in shaping the ethical environment affecting job satisfaction.

Moreover, our findings indicate the trade-off between the management-relevant guide (i.e., mission statement or management philosophy) and ethical standard (i.e., ethical climate or low ethical ambiguity). Specifically, straightforward mission statement quality and romanticism management philosophy are substitutes when ethical climate or low ethical ambiguity is present (S1, S2, S3, and S5). However, it is found that for creating employee job satisfaction, both mission statement quality and romanticism philosophy are required when external and internal ethical standards are missing (S4). In contrast, employees will obtain high levels of job satisfaction when they perceive high ethical climate levels and have low levels of ethical ambiguity in their workplace simultaneously (S6). Based on these findings, we conclude that explicit management-relevant guides and specific ethical standards are equivalent to achieving high job satisfaction. Ethical standards stemming from either external ethical climate or internal low-ethical ambiguity can act as viable alternatives for causing high job satisfaction when employees cannot perceive a clear mission statement and management philosophy. Missions determine manners and behaviors that are most related to the values and strategy. Therefore, when top values such as honesty, commitment, respect, and integrity are considered in the mission statement, a higher level of ethical climate is expected that reminds the importance of mission statement as a vital strategic tool promoting job satisfaction.

6Theoretical implicationsThis study introduces a fresh theoretical perspective for understanding cause-effect relationships between critical conditions and job satisfaction. Different pathways leading to high job satisfaction are identified based on fuzzy set QCA, which allows for better knowledge on what conditions of a configuration are relevant for job satisfaction and how these conditions combine to achieve their effects. The current study also represents a step toward developing a more in-depth understanding of the crucial role of emotional competence in terms of job satisfaction, which is a preferred outcome for organizational behavior literature. Our findings imply that the necessity of high-quality mission statements and romanticism management philosophy depends on an ethical guide's clearness regardless of whether an ethical guide is built upon an external climate or internal mindset. An example of ethical conduct is very crucial for creating employees’ job satisfaction. These findings carry direct implications for the growing literature on ethical leadership (Brown et al., 2005).

7Practical implicationsThis study provides practical implications and actionable approaches for practitioners and firms that want to foster employees’ high job satisfaction. First, the findings indicate that there is no universal formula for developing job satisfaction. Every firm has its problem, such as unclear mission statement, a lack of romanticism management philosophy, a deficiency of ethical climate, or employees who are ambiguous on the ethical issues. The evidence that shows multiple pathways are leading to job satisfaction allows firms to find their strategy through the facets that are most suited to real situations.

Our findings suggest that managers’ emotional competence is a core condition for building proper conditions leading to the outcome, which makes it evident that competence is vital to satisfy employees. Thus, professional development and training for maintaining or improving managers’ competence are significant for firms and managers. Specifically, in order to satisfy employees, managers need to always be in control of situations that can affect their emotions. Furthermore, managers should always maintain positive expectations for their employees. More than anyone, managers have to anticipate the difficulties that hinder the ability to complete the job. If there are obstacles, managers actively change to make a difference. One of the other crucial emotional competence qualities is that the manager's sense of humor can provide a more comfortable working atmosphere. When working in groups, the leader can encourage participation from the members and proactively give constructive feedback. Ultimately, this can refine ideas based on new information and know-how to set measurable goals to challenge employees’ growth and creativity.

Researchers also find that an effective formula for high job satisfaction depends on a balance between the management-relevant guide (i.e., mission statement or romanticism management philosophy) and ethical standard (i.e., ethical climate or low ethical ambiguity). Therefore, firms are advised to be aware of how employees perceive the mission statement or management philosophy. Leaders ought to encourage awareness of the mission statement to the entire staff in an organization. After all, the staff receives a romanticism management philosophy. They can make over into their claim missions to attain the general objectives of the organization.

If employees do not explicitly receive this management-relevant guide, they require demonstrating a concern for ethical issues. Using ethical leadership is one of the approaches to build an ethical climate or to lower employees’ ethical ambiguity as it can act as one reasonable elective for causing job satisfaction. Leaders should especially characterize and adjust their values, recruit employees with comparable values, advance open communication, avoid bias, and lead staff by examples, to mention a few.

Overall, to level up employee satisfaction, practitioners should develop plans or initiatives aimed at improving the perception of organizational ethics. Meanwhile, strengthening the spirit of teamwork and boosting the sympathetic, working climate should be considered. The results also offer practical implications for decision-makers and higher-level managers in a way to provide a holistic knowledge of the essential factors that elevate job satisfaction, especially in private sectors.

8Limitations and future researchThis study has some limitations that provide directions for future research. First, researchers collect data of all variables from respondents simultaneously using the same survey administration. We employed Harman's single-factor approach (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Podsakoff & Organ, 1986) for examining the potential of common method bias (CMB). However, the result shows that this bias is not an issue. We encourage future research to collect data at a different time. Second, other several variables have been identified to be related to job satisfaction in the literature. This study only focuses on the organizational environment and managers’ competence that are central to the workplace and embrace employees. Future research can explore different combinations by considering other possible conditions leading to high job satisfaction in order to add more perspectives to the literature. Finally, due to the limited data, researchers do not consider the specific type of industry. Beside conducting data collection in only Mongolia is another restriction. Moreover, the contextual factor, which may influence the results, can be controlled. Therefore, we encourage future research to conduct a cross-industry or cross-cultural study for comparing causal recipes for job satisfaction.