Edited by: Sascha Kraus, Alberto Ferraris, Alberto Bertello

More infoWith its five-decade history, the literature on alternative workplaces, working time arrangements, and related issues now represents a relevant quantitative and qualitative articulate corpus regarding topics addressed, approaches applied, analytical tools implemented, and terminology used. Due to its complexity, this corpus appears as an indubitable labyrinth. However, it is unnecessary to be perplexed by this maze. It can be exited and the contributions hidden within it can be of value. This article presents a literature review of three different and related objectives: (a) to investigate the different conceptualizations and terminologies used for analyzing workplace arrangements (research streams), (b) to analyze the results of the individual streams to identify elements of overlapping and differentiation while tracing the connections between them, and (c) to identify future research guidelines for single streams and the entire field. We analyzed 344 academic publications. Our qualitative content analysis of the articles allows us to investigate the peculiarities of each research stream and grasp the relationships between them. We supplemented our analysis using Leximancer, a conceptual mapping tool. This article contributes heightened clarity in the complex research field of workplace arrangements. We provide a map of research streams assisting researchers to move across the labyrinth and introduces redesigned research avenues for the purpose of sharing insights and progressing straightforwardly. Increasing clarity within the field allows fellow researchers' contributions to be more accessible to practitioners, reducing their effort in finding relevant work and researchers.

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically increased the use of alternative workplaces and working time arrangements, and changed work situations for nearly everyone employed (Wendt et al., 2021). Working on companies' premises was not often allowed by law, therefore, a large portion of the workforce worked from home. With the increased possibility to work elsewhere other than in the office, numerous employees used this opportunity to spend time at remote locations or even in different countries by working online.

Besides spatial and temporal flexibility, work arrangements changed regarding information and communication technologies (ICTs), collaboration with co-workers and supervisors across relational boundaries, contractual arrangements, family-friendly working conditions, and technological surveillance (Abendroth et al., 2022; Thulin & Vilhelmson, 2022; Vayre & Pignault, 2014; Vlaar, van Fenema & Tiwari, 2008). However, evolving work arrangements are not new and have been a topic of interest since the 1970s (e.g., Nilles, 1976). Many studies have already examined different work arrangements (e.g., Chung & van der Horst, 2018; Dutcher, 2012; van Zoonen & Sivunen, 2021). The sheer volume of studies might suggest that research in these fields has reached a mature stage of theoretical development, but this is not the case. There has been no attempt to define the different work arrangements comprehensively, and it remains unclear which research stream to consult when dealing with different work arrangements.

To date, the terminology used to describe different work arrangements is blurred and overlapping. For instance, Vayre and Pignault (2014) state that "there is no consensus on how to define and understand teleworking" (p.177). Thus, neither researchers nor practitioners have arrived at a common definition of telework or related concepts such as telecommuting, working at home, remote working, smart working, home office, or virtual work. Furthermore, researchers mention that "the absence of shared understanding of work performed outside of the conventional working place creates difficulties to studying this phenomenon" (Nakrošienė et al., 2019, p. 89).

Referring to these aforementioned works, the necessity to clarify and unify the terminology used becomes obvious. However, the limitation imposed by the status quo impairs further theoretical development of the research streams on forms of work arrangements and makes it challenging to offer sensible guidance to scholars and practitioners.

Pianese et al. (2022) state that "More research should be devoted also to define a shared terminology on new work arrangements […] and reconcile the perspective of organizations and employees on flexibility" (p.13). Accordingly, the objective for this paper is to provide a more substantive picture, by clarifying the content domains of, and theoretical connections between numerous research streams focused on different work arrangements.

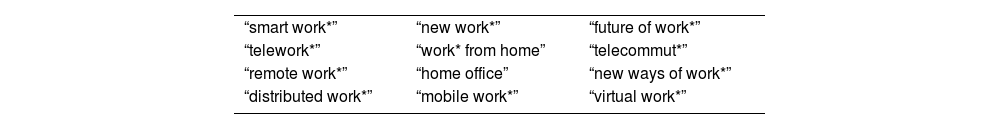

Other researchers before us probed into some isolated and even overlapping areas of this topic's complexity, e.g., Felstead and Henseke (2017) on remote work or al., and Maruping (2019) Correct: Raghuram et al. (2019) "?>Raghuram et al. (2019) on virtual work. However, we opted for a broader approach, choosing no less than twelve different introductory points in the labyrinth of future of work-related literature (see Table 1). We probed deeply into each corridor for concepts, found pathways between definitions, and shifted barriers of constructs. This review supports researchers and practitioners by facilitating them in their choice of which research stream to pursue, and providing guidance when addressing topics related to the future of work.

The first objective of our review article lay in assisting researchers find their way through this maze without getting lost. To achieve this, we mapped the trajectory of theoretical and methodological development in future of work-related literature. We extended existing research by conducting a review that captures the breadth of the field and the related streams, creating a shared understanding for engaged scholars and practitioners. The second integrated goal was to destroy superficial barriers between adjoining, sometimes interchangeable, concepts to establish concept clarity. Hence, we synthesized and extended theory by establishing a comprehensive picture of connecting and differentiating characteristics between the literature streams on work arrangements. Finally, our third aim lay in providing an outlook on where those extensive paths would take research once we combined forces. Ultimately, “killing the minotaur” by focusing on investigating and shaping the future of work is challenging enough without considering a labyrinth of our own making. Basically, we built greater coherence within a tremendous amount of research to contribute to the identification of possible future research guidelines.

Thus, the following questions led our review: (1) Which relevant research streams related to the future of work exist? What is their focus, and how did they develop theoretically and methodologically? (2) Which characteristics connect these research streams, and how can we distinguish between them? (3) Finally, we asked what future research guidelines will be promising and where complicity should occur.

With our review, we contribute to the discourse on the future of work and related literature by establishing an overview of existing research streams and their foci. Foremost, we state concrete suggestions on how the broader field would profit from focusing streams on specific topics (e.g., virtual work on topics related to augmented reality or the metaverse) and from discontinuing to publish research under catch-all phrases and buzzwords such as new work or future of work.

This conceptual clarity will also benefit practitioners and policymakers alike, as finding streams, articles, and scholars of interest will be much easier for non-scholars.

Scope of the review: Outside walls and entry pointsAdvances in ICTs have allowed an increasing number of organizations to adopt new work arrangements differing from traditional work in temporal, spatial, and other aspects (Pianese et al., 2022). Many firms have announced their interest in or have already adopted these ways of working in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the near future, investments in alternative work programs are among the priorities of their digital agenda (Pianese et al., 2022). Over the last five decades, researchers have developed conceptualizations and terminologies for work arrangements differing from traditional settings. Among others, these include future of work (Santana & Cobo, 2020), new work (Aroles et al., 2021), telework (Taskin & Bridoux, 2010), telecommute (Sia et al., 2004), remote work (Pianese et al., 2022), distributed work (Bélanger & Collins, 1998), or virtual work (Raghuram et al., 2019). Individual theoretical and even methodological developments characterize each research stream. Furthermore, academics and practitioners adapted prevailing explanations on alternative work arrangements or created entirely new definitions (Abendroth et al., 2022), which increased ambiguity. Consequently, this study reviews several literature streams bordering or potentially subsumable under the topic future of work. We aim to support researchers and practitioners in selecting the proper research stream to pursue and provide guidance when dealing with different aspects of future work arrangements.

Methodology: Preparing to enter the mazeWe designed our research to investigate several often-overlapping concepts related to the general term future of work. This analysis identifies delimiting characteristics between the fields to establish concept clarity, highlights commonalities to determine common paths, and proposes how the overall field could move forward to increase contribution through clarity.

Literature reviewWe base the description of our methodological approach on the RAMESES scheme, which addresses semi-structured meta-narrative reviews, "a relatively new method of systematic review, designed for topics that have been differently conceptualized and studied by different groups of researchers." (Wong et al., 2013, p. 2). This form of review gains increasing interest in management research due to its meta-narrative approach, which aims to integrate several research streams with different historical backgrounds and paradigms (Snyder, 2019).

We defined nine starting concepts from the existing literature to initiate our literature search on Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) and later expanded the focus by adding three concepts to the review based on their emergence in the already screened articles and their influence on the overall field. This resulted in the final twelve concepts and the search terms used, as depicted in Table 1.

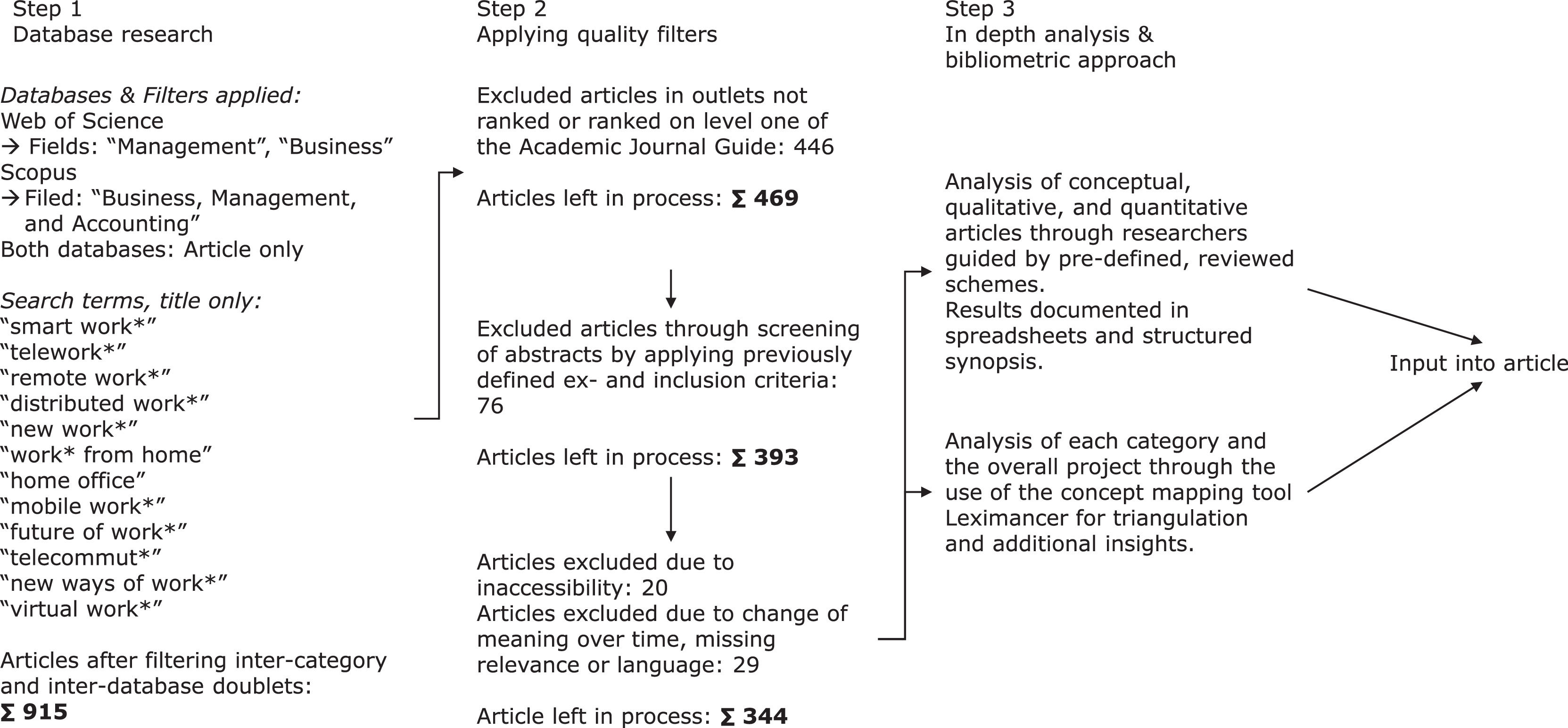

We started with 5,632 hits on WoS and 5,935 hits on Scopus by searching for appearance in title only. Then, we limited our search to the fields of Business and Management (WoS) and Business, Management, and Accounting (Scopus), leading to 777 and 1,245 results, respectively. Next, we focused on articles only and correcting for inter-category and inter-database doublets with and between databases, we were led to 915 articles.

In the following step, we applied a quality threshold (see, e.g., Kraus et al., 2020) by excluding all articles published in journals not listed in the British Academic Journal Guide ranking (303 articles) or rated below '1' (143 articles), which left us with 469 papers to analyze.

In the next step, we screened titles and abstracts of ten articles, applying pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to each. We excluded literature reviews not marked as such, articles with search terms only of contextual and not focal relevance, or part of a formulation with different meaning. Afterwards, we screened all abstracts applying these criteria, resulting in 393 papers. Of these articles, we excluded another 49 at a later stage: 16 due to a total change in the meaning of the search term, language, or missing relevance becoming obvious only at in-depth analysis; 13 articles revealed to be previous literature reviews and were thus used to triangulate our insights, but not included in our review, and another 20 articles which were inaccessible via two universities as well as through directly contacting the authors. These steps led to a final sample of 344 articles. We have depicted the identification process in Figure 1.

Exploring the maze in a traditional wayThree researchers developed a standardized analysis scheme for conceptual and qualitative articles and a separate one for quantitative articles. Another author reviewed this scheme, her suggestions were discussed, and the scheme was adapted accordingly (similar to, e.g., Aguinis et al., 2022).

We then divided the categories for analysis between the authors. After the first step, the analysis began with categories of the fewest articles to discuss and adopt to the process. We continued the procedure after minor changes to the documentation, and screened qualitative and conceptual papers for (a) methodology, (b) definitions and conceptualization of the topic in focus, (c) central topic, and (d) results where applicable.

We screened quantitative approaches for (a) methodology, (b) definitions and conceptualization of the topic in focus, (c) up to three focus topics, and (d) up to three key results.

We documented the analysis results for each article in spreadsheets. Then we authored a synopsis of each category, outlining its central topics, its development over time, commonalities with other concepts, where evident, and future research guidelines or suggestions to combine the stream with others. In the last step, we merged the reports and spreadsheets into the two subsequent sections, generating concept clarity, forming an integrative perspective of the concepts surrounding the literature on future of work, and providing an outlook on the field's possible developments.

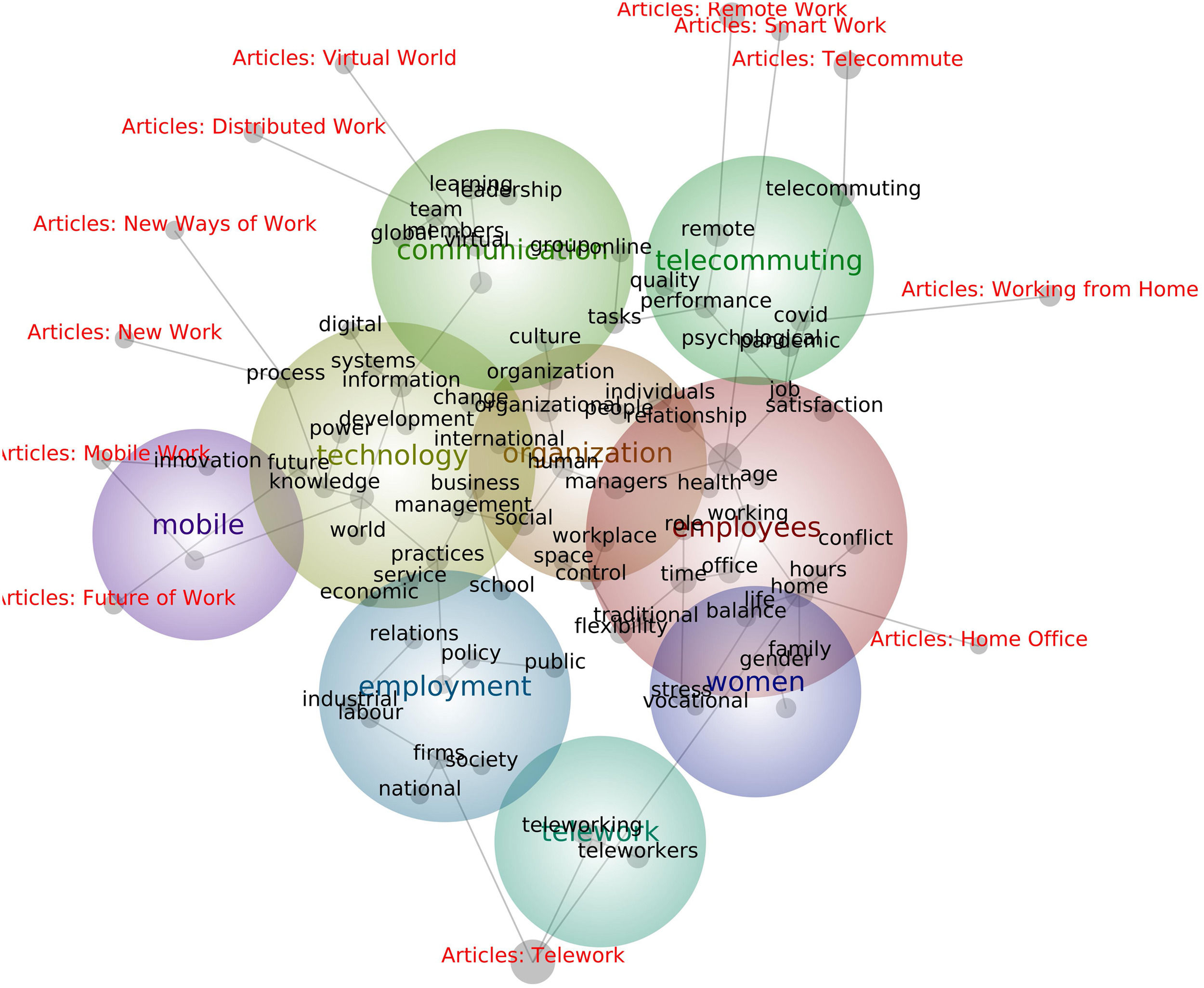

Implementing technology for mapping the mazeSupplementing our rigorously conducted 'traditional' review approach to the field, we applied a bibliographical analysis process described by Donthu et al. (2021). We drew upon Leximancer, a text-mining software for concept and theme analysis, to provide an integrative overview of the field. This software identifies concepts (keywords) through semantic and relational extraction. Based on a Bayesian co-occurrence metric with bootstrapping, Leximancer provides a concept map, visualizing the identified concepts as networks on a map through an iterative process. Overarching themes represent the connectedness between the concepts (size of themes), the relevance of the themes (color-coded), and their distinctiveness from each other (distance between themes) (Smith & Humphreys, 2006). With the provided visualization and the opportunity to explore relationships in-depth through accessible information, e.g., co-occurrence of terms, management scholars are increasingly using the software to generate input into large fields of literature (e.g., Wilden et al., 2016; Wilden et al., 2019).

We analyzed the same 344 articles with default settings, each attributed to its field, having Leximancer develop an initial concept seed set of 158 concepts. Next, we excluded 38 irrelevant terms (e.g., "analysis," "data," or "model") and merged 40 terms (e.g., "team" and "teams"), leading to 100 concept seeds for initial analysis. Finally, we kept terms serving as "kill concept" to exclude the bibliography section of the analyzed articles in the next step (i.e., "vol.", "journal," or "press"). In the next step, we analyzed the thesaurus generated by Leximancer and proceeded to define the kill concepts mentioned above to exclude references from the analysis. Finally, we generated concept maps and screened the synopsis for references, identifying additional kill concepts to avoid excluding relevant data. This iterative process also revealed the map's stability, as repeating the process with slide adaptations did not change concepts and topics (Wilden et al., 2019).

Within the concept map, we adapted the theme size from 60% (default setting Leximancer v. 5), revealing four themes (i.e., employees, technology, telework, and telecommuting) to 33% (default setting Leximancer v. 4) to allow for nine concepts to emerge: communication, employees, employment, mobile, organization, technology, telecommuting, telework, and women.

Stream-specific results: Climbing the walls - a perspective on the definition and developments of related constructsAs advocated by al. (2020; 2022) in their..."?>Kraus et al. (2022; 2020) in their recent works on the methodology of review articles, we followed a two-step approach by combining content analysis with bibliometric results (see, e.g., al., and Nielsen (2019) Correct: Vallaster et al. (2019)"?> Vallaster et al. (2019) or al., and Covin (2021) Correct: Wales et al. (2021)"?>Wales et al. (2021) for similar approaches).

For each of the included categories, we first provided a quick overview of the metrics (i.e., development over time, number of conceptual articles, and number of qualitative and quantitative studies included). Afterwards, we turned to common central components of the definitions and closed with a description of the field, its focus, and its development over time. The described process held true for all but two categories: future of work and new work. Both categories' vagueness and generic nature made it impossible to identify definitions which led to our attempt to conceptualize them.

Future of workWhile this category forms the basis for this article, it also proved to be the hardest to grasp. We included 21 articles of this category in our review, published between 1976 and 2022. Of these, four were qualitative, one was quantitative, and 16 were conceptual. A terminological indistinctness of the field became evident when noting that none of the articles included a clear definition, and few offered a precise conceptualization of the term. While researchers recently published reviews on the core topic (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2022; Santana & Cobo, 2020), these ignored related fields, and no definition emerged.

The key question, recurring in the field, focused on how work will change in the next few decades because of the constant changes affecting the economic and social phenomena that form the backdrop to work (Schlogl et al., 2021). The breadth of the topics covered risks giving the term future of work an evanescent, unclear, and sometimes contradictory meaning. Nevertheless, certain elements emerged more frequently in our review of the focal literature.

First, technological innovation has been assigned a prominent role among the causes of the ongoing changes impacting work. The impact of technology on work is a classic theme that runs through no small part of economic thought. Therefore, it is not surprising that this theme plays a prominent role in the presence of disruptive innovations (Kudyba et al., 2020).

Additional sources of change, such as demographic dynamics, the related issues for welfare models, public policies, globalization and its impact on business models and strategies adopted by companies, or sustainability issues, add to the dynamics of the research field (Ainsworth & Knox, 2022; Khanna & New, 2008).

The outlined changes impact work differently: Companies pursue greater flexibility in work relationships to maintain or strengthen their competitiveness. They require new skills, develop new organizational forms, and establish new legal arrangements for employment relationships to meet these needs (Lowe, 1998).

In this vein, researchers analyzed the development of jobs carried out outside companies’ premises and investigated their impact on leadership style, employer-employee relationship, work-life balance, and workplace re-design (Antonacopoulou & Georgiadou, 2021).

However, the authors noted contradicting results in the literature on future of work regarding researchers' approach to explaining this work arrangement. For example, whereas Mitchell et al. (2022) related future of work to telecommuting, literature has pointed out that al., and Malatzky (2021) Correct: Couch et al. (2021)"?>Couch et al. (2021) shifted future of work to the research stream of working from home, which increases overall ambiguity.

New workLike future of work, our analysis of thirteen articles on new work included in this review lead us to believe that the category must be understood as generic, bracketing a large, diverse set of study areas and directions. Compared to the following categories, new work focuses less on technological-driven change and more on organizational topics. Behind the use of the term stands the idea that, at least for an increasing proportion of workers, the way they carry out their work is changing. The term new indicates the presence of several elements featuring today's labor relations. These appear innovative compared to the traditional way of understanding work based on well-defined working hours, rigid procedures to be followed, and little autonomy for the worker. According to Schmitz et al. (2021)new work is conversely featured by "flatter hierarchies or network structures […] a new organizational culture of trust, and focus on participation and collaboration" in addition to "flexibility in working time" and the development and implementation of "new office concepts" (p. 321).

Underlying these changes is a broad spectrum of phenomena that reshape the features of labor relations, the firms' organization, and working activities. These phenomena include legislative innovations concerning the rules governing the employment relationship, the implementation of new work practices (e.g., job rotation, teamwork, greater job autonomy, and enhanced upward communication), and the increasingly decisive role of technology (Ramirez et al., 2007).

Empirical papers included in the category investigated whether and to what extent these phenomena impact aspects such as the workers' effort, the employment opportunities for immigrants, the attractiveness of the firm for potential workers, the effectiveness of carried out activities, the core features of an employment relationship, or the sensemaking of employees facing relevant changes. Furthermore, some papers analyzed factors, such as country-specific features or roles played and actions undertaken by unions, able to impact the adaptation of new work practices (Ollo-Lopez et al., 2010).

All 13 papers were published in this century, four in 2021, demonstrating the timeliness of the subject. However, work characteristics are currently and likely to be subject to further relevant changes, which will be essential to study with further analysis.

Over the years, new work literature has focused on organizational topics rather than employees. Even if researchers focused on the individual level, they produced mixed approaches in describing employees in the new work context. These descriptions ranged from e-worker (Bell, 2002) to nonstandard workers (Ashford, George, & Blatt, 2007) without finding common ground. This presents an exciting opportunity to expand the scope of research on the individual level, e.g., by identifying a terminological basis regarding employees in new work while also addressing the role of gender, well-being, or work-family interface in this work arrangement.

Telework"Telework is a broad and complex phenomenon that lacks a commonly accepted definition" (Nakrošienė et al., 2019, p. 98). This statement is of little surprise when considering that the category of telework represented more than a third of all articles included in this review, with 22 conceptual, 34 qualitative, and 83 quantitative or mixed studies, 139 articles written from 1984 until 2022 (121 since 2000 and 18 since 2020).

As telework is a multi-faceted phenomenon, Vayre and Pignault (2014) stated that neither researchers nor practitioner organizations have been able to arrive at a standard definition of telework according to its various concepts such as telecommuting, working from home, working at a distance, remote working, home (office) working, and virtual work. We needed to consider several dimensions to establish a common understanding of telework. Regarding transportation, early conceptualizations of telework tend to focus on its potential to avoid commuting (Sullivan, 2003). Due to the working location, telework is a form of organizing and carrying out professional activities outside the employing organization's worksite (Vayre & Pignault, 2014). Depending on the working location, researchers identified three types of telework: home-sed teleworking, remote offices, and mobile working (Vries et al., 2019).

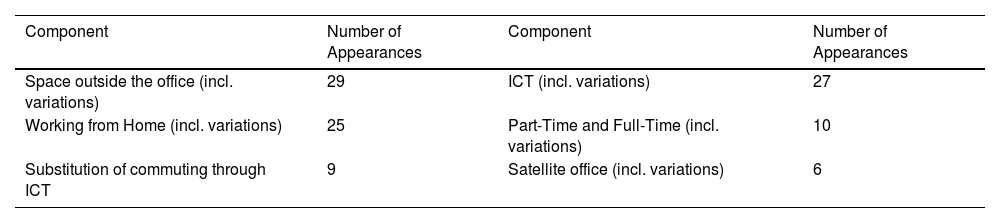

Regarding the amount of time working remotely, employees can perform work exclusively at home or in remote offices on a full-time basis. In contrast, alternating telework enables employees to split their working time between the employing organization's worksite and the home (Tietze, 2002). Temporal flexibility, a further dimension of telework, distinguishes between full-time and part-time teleworkers. Whereas full-time teleworkers complete most of their work during regular hours and add evenings and weekends to recoup work, part-time teleworkers work only evenings and weekends (Dimitrova, 2003). As work becomes disconnected from time and space conventions, Chung and van der Horst (2018) described telework as flex, enabling employees to control their working times and location. More specifically, flextime entails workers' ability to change the timing of their work regarding the starting and ending times and to fluctuate the number of hours worked per day or week (Chung & van der Horst, 2018). One of the most fundamental elements for defining telework is the use of information and communication technology (ICT) which ranges in terms of hardware (such as computer, laptop, modem, and smartphone) and software (such as Wi‐Fi, videoconferencing, e-mail, 3G, access to employers' computer networks) (Daniels et al., 2001; Sullivan, 2003) for carrying out work from a remote location. In terms of control, ICT affords opportunities to integrate technological and bureaucratic control (Thulin & Vilhelmson, 2022). By facilitating a constant real-time flow of information regarding employees' performance, ICT enables employers to electronically monitor and regulate the work performance of teleworkers at a distance (Bathini & Kandathil, 2019; Thulin & Vilhelmson, 2022). Regarding a teleworker's affiliation with an employer, employed teleworkers are still generally involved in occasional commuting to work, and their workflow is supervised externally by their organization (Dimitrova, 2003). In contrast, self-employed teleworkers are responsible for their workflows (Baines, 2002). Table 2 provides an overview of definitions and conceptualization components.

Key-components of telework definitions & number of appearances

Researchers focused on telework by examining how knowledge workers and organizations adopt telework as an alternative work arrangement (Jaakson & Kallaste, 2010). To explore the acknowledged problems of defining telework and assess whether the term is still valid today, Wilks and Billsberry (2007) examined criteria used to characterize teleworkers in recent literature. While looking into the household of the self-employed teleworker, Baines (2002) showed how uncomfortably work can fit into the physical and emotional space of the home. Thus, they explored the reasons and identified barriers why working at home on a full-time basis has not been more widely adopted by employees and implemented in organizations (Baines, 2002). Regarding the work and family interface, researchers investigated the relationship between work and family roles, and gender among home-based teleworkers and their families (Sullivan & Lewis, 2001), as well as changing work-family interdependences (Tietze, 2002). In this vein, Fonner and Stache (2012) examined the strategies home-based teleworkers use to manage the work–home boundary and the cues to facilitate transitions between work and home roles.

Regarding gender-based studies, researchers examined female teleworkers' domestic work experiences during the COVID‐19 lockdown (Çoban, 2021). By focusing on ICTs, the main objective of, e.g., Dimitrova (2003) was to explore how the work context shapes control and autonomy in telework, how to achieve control, and how control procedures and practices vary across workplaces. Regarding social support and physical isolation, Vayre and Pignault (2014) addressed how teleworkers perceive and organize their relationships with others, e.g., work colleagues, supervisors, family members, and close friends. In addition, Taskin and Bridoux (2010) showed how telework may endanger an organization's knowledge base by threatening knowledge transfer between teleworkers and non-teleworkers.

Even as research on telework has grown remarkedly over recent years, it lacks a systematic attempt to comprehensively structure and connect the variety of its disconnected literature. Consequently, it serves as a catchall phrase. Therefore, we advocate systematically analyzing this research stream from a theoretical and methodological perspective in a separate literature review. Nevertheless, we shall propose a future direction for the stream in an integrative perspective on all research fields included. In addition to the organizational adaption of telework and employee-related factors, research on telework offers limited insights into developing innovations and related management of information when teleworking. This presents an attractive opportunity to expand the scope of research, which is especially important for managing, e.g., knowledge workers over geographical distances.

TelecommutingWith 64 papers, telecommuting is the second largest category of the review. About half of them appeared between 1984 and the end of the last century. Since 2000, almost all the papers have presented a quantitative analysis. The twelve conceptual articles indicated the importance of the topic. Eleven qualitative and 41 quantitative articles represented the interest in and the complexity of the topic.

Nilles (1976) coined the term telecommuting. The term draws attention to the substitution of travel towards employers' premises through ICTs. In this setting, the workplace is either the employee's house, thus wholly avoiding physical commuting, or a place close to it, reducing commuting.

In the following decades, the meaning of telecommuting has broadened. For instance, workplace flexibility has expanded to refer generically to locations other than the employer's premises. Today, the critical elements of the definitions and conceptualizations of telecommuting are workplace flexibility and communication technologies. In addition, some authors pointed out that telecommuting can cover all or part of the employee's regular working hours (Mayo et al., 2009; Olszewski & Mokhtarian, 1994).

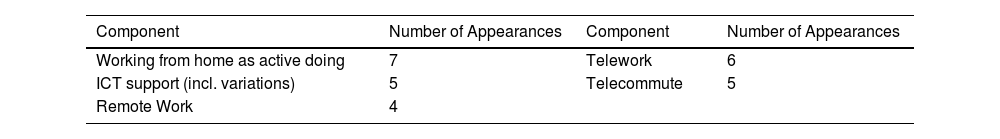

We have provided an overview of the central concepts included in the definitions and conceptualization in Table 3.

Key-components of telecommuting definitions & number of appearances

The topics of research in telecommuting have evolved over time. This change certainly has been influenced by the significant technological evolution that has taken place in almost four decades, separating the first works on the subject from today.

Despite this varied picture, it was possible to outline research streams characterizing this category's contributions. The first stream includes studies that analyze the spread of telecommuting, explores its determinants (e.g., the characteristics of the company, of the worker, and of the employment relationship that make the adaptation of this work setting more or less likely), and investigates possible social implications (Mannering & Mokhtarian, 1995).

The second line of investigation explores the effects of telecommuting implementation on workers. It analyzes, for example, the potential benefits telecommuters might obtain and the drawbacks they could face. In addition, it addresses the potential impact of telecommuting on workers' job satisfaction, their engagement with the company, their turnover intentions, and their perceptions in terms of career and salary growth opportunities, as well as a sense of isolation and justice inside the company (e.g., Golden & Veiga, 2005).

Finally, the third line of inquiry focuses on the impact of telecommuting on an employer, its organization, and its performance. On this last point, in particular, the impact on costs and productivity is analyzed (Dutcher, 2012; Neufeld & Fang, 2005). In this area of investigation, analysis was carried out on the changes that the implementation of telecommuting makes necessary in terms of organizational structure, leadership style, internal communication, compensation systems, and, more generally, human resource management (Dahlstrom, 2013; Lautsch & Kossek, 2011). Studies also analyzed the impact of company choices on the degree of satisfaction of telecommuters, their behavior, and productivity. These studies focused on the technological aspects of telecommuting (Kuruzovich et al., 2021). In addition, in recent years, several studies have analyzed telecommuting in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Jamal et al., 2021).

However, the authors noted there are contradicting perspectives on the spatial flexibility to perform one's tasks outside the company's offices. While Kossek et al., and Eaton (2006) and Golden and Gajendran (2019) referred to telecommuting exclusively when addressing working from home by being supported with telecommunications technology, al., and Ramioul (2022) Correct: Vanderstukken et al. (2022)"?>Vanderstukken et al. (2022) described telecommuting in a broader context in terms of telework, remote work, distributed work, and flexible work to perform tasks elsewhere than in a central workplace. This limitation impairs further development of the telecommuting research stream, and thus, we suggest establishing a shared terminology and a clearly defined research domain. According to extensive research on telework over the years, an overview of multiple facets of this work arrangement is necessary for a holistic understanding.

Remote workFelstead and Henseke (2017) stated that defining remote work and its operationalization is still a central topic in the field. Based on the 41 articles reviewed throughout the process (ten conceptual, 14 qualitative, and 17 quantitative), we can agree that the definitory meaning of the field is fragmented.

Researchers defined remote work as a flexible work arrangement in which employees have control to work at locations beyond the employing organization's worksite (Perry et al., 2018). From a geographical perspective, remote workers can work from home, in satellite offices, in neighborhood work centers, and on the road (Van Zoonen et al., 2021). Remote work ranges from workers who occasionally work away from the organization's worksite to fully remote workers who may be located anywhere in the world and permanently work away from the organization's worksite (McDonald et al., 2022). Although different in form, all these work arrangements involve time spent working at a geographic distance from a supervisor and colleagues. This modus operandi reduces in-person supervision and replaces face-to-face interaction with technology-mediated communication (van Zoonen & Sivunen, 2021). Employees use ICTs to interact with others inside and outside their organization (Shirmohammadi et al., 2022). In this context, it seems that researchers described working remotely as a way of conducting one's work rather than a specific work location. Delany (2021) argued that a remote worker refers to a "location-free workforce" (p.5) provided with the technology needed to perform one's professional duties outside of the company's offices. From the perspective of working times, employees can work at any time, outside conventional working hours, if they can access the internet and official systems to complete their allocated assignments (Chatterjee et al., 2022).

We have provided an overview of the most common definitional components in Table 4.

Key-components of remote work definitions & number of appearances*

It seems remote work has gained increasing empirical interest, closely scrutinized from diverse lenses with quantitative, qualitative, and conceptual approaches, e.g., the consequences of remote work on work effort, job-related well-being, and work-life balance (Felstead & Henseke, 2017) as well as emotional stability and autonomy (Perry et al., 2018). Studies have examined the influence of remote work on worker performance (Jensen et al., 2020) and organizational performance (Sherman, 2020). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the consequences of the widespread switch to virtual work is the impact on the relationships and interpersonal networks within organizations. Waight et al., and Smith (2022), e.g. studied how working remotely can damage employee social connections and trust. Furthermore, research focused on aspects of sustainable practices and identified challenges facing organizations adopting remote work (Delany, 2021; Laat, 2022). Regarding the challenges when working from home, researchers investigated how remote work practices, ICT use, and work stressors relate to psychological strain (van Zoonen & Sivunen, 2021; Van Zoonen et al., 2021). Regarding the work-family interface, Shirmohammadi et al. (2022) focused on individual differences in work-family conflict. To mitigate psychological strain, Bouchard and Meunier (2022) identified specific management practices that promote the psychological health of remote workers in the context of COVID‐19. Regarding human resources development, researchers examined how employees can enhance their skills and knowledge for career development and progress (Yarberry & Sims, 2021).

We found contradicting results when looking closely at the research stream remote work. Whereas al., and Seidel (2005) Correct: Barsness et al. (2005)"?>Barsness et al. (2005) mentioned that remote workers can work from home, in satellite offices, in neighborhood work centers, and on the road, al., and Marin (2021) Correct: Zhang et al. (2021) "?> Zhang et al. (2021) referred to remote work as the standard concept of working from home. Thus, terminological differences obfuscate comparing results from a single research stream.

Regarding remote work, research still lacks an understanding of the effects of new technological tools on organizational control and surveillance in alternative work arrangements. Pianese et al. (2022) emphasized that future efforts should investigate organizational control in flexible work practices and alternative work arrangements (e.g., smart work), an aspect we strongly support.

Working from homeWith the oldest paper in our study stemming from 1999, and 16 out of 21 articles published after 2020, this field belongs to the most recent included in our study. With one conceptual, five qualitative, and 15 quantitative articles, the field has a strong positivistic influence, even though we perceived its conceptual foundation as weak; while determining common definitional building blocks, the references to other concepts almost outweighed the definitional components.

A variety of researchers like Bellmann and Hübler (2021), al., and Gursoy (2021) Correct: Chi et al. (2021)"?>Chi et al. (2021), Khan (2021), and van der Lippe and Lippényi (2020) have developed their definitions and explanations to describe working from home. In essence, working from home refers to working from a non-office location, usually an employee's home, to fulfill the duties of one's job by utilizing information and communication technology during or outside regular work hours (Chi et al., 2021; Khan, 2021). Thus, working from home is described as a family-friendly workplace arrangement (Abendroth et al., 2022) in which employees do not commute to their workplace in the company (Bellmann & Hübler, 2021). Nevertheless, studies showed that working from home is also called remote work, telecommuting, telework, homework, home office, mobile work, outwork, and the flexible workplace (Bellmann & Hübler, 2021; Dockery & Bawa, 2018). Table 5 provides some insight.

Researchers investigated the implementation and administration of working from home initiatives in organizations (Venkatraman et al., 1999), as well as various individual and organizational outcomes of working from home in terms of employees' job satisfaction, career opportunities, productivity, individual and team performance, and work-family conflict (Dockery & Bawa, 2018; Nakrošienė et al., 2019; van der Lippe & Lippényi, 2020). From a political perspective, al., and Venkateswaran (2021) Correct: Jones et al. (2021) "?>Jones et al. (2021) addressed the nature and timing of policy responses to COVID-19 to encourage working from home. Furthermore, researchers investigated the extent and nature of changes in the domestic division of labor allocations (Garcia, 2022) and how working from home has impacted the experience of interruptions during work time (Leroy et al., 2021). Research also focused on disabled employees' likelihood and experiences of working from home relative to non-disabled employees (Hoque & Bacon, 2022).

Studies over the years have produced mixed results on the effects of working from home, which seem contradictory (Yeo & Li, 2022). Whereas working from home has the potential to increase an individual's work-life balance, employees are frequently confronted with interruptions from home and working longer hours which negatively influence an individual's work-life balance (Nakrošienė et al., 2019).

Research on working from home is limited at the organizational level, and a comprehensive overview of factors that impact organizations' resilience regarding the ability to work from home is missing (Fischer et al., 2022). Future avenues for research should go beyond the scope of the employed set of variables in their study. As Bellmann and Hübler (2021) examined the effect of working from home on job satisfaction and work-life balance, scholars should consider a broader range of context variables, e.g., job characteristics, commitment, and collegiality effects.

Virtual workWe included 13 articles on virtual work in our review. Out of the 13, there were three conceptual, four qualitative, and six quantitative articles, all published within this century. Two key points features the definitions and conceptualizations of virtual work: (a) the possibility to work from places other than the company premises and (b) the use of ICT allowing this spatial dispersion. Further elements pointed out by some authors are the potential temporal flexibility and the possible involvement of people living in different countries (global virtual work) (Nurmi & Hinds, 2016). In 2019, Raghuram et al. (2019) al. to the reference list? It is the following already existing source in the reference list: Raghuram, S., Hill, N.S., Gibbs, J.L., & Maruping, L.M. (2019). Virtual work: Bridging research clusters. The Academy of Management Annals, 13(1), 308\055341."?> carried out a review aimed at detecting the key research stream referred to as virtual work, exploring the potential synergies among them. With its generic setup, virtual work now poses as a meta-category or umbrella term, comparable to telecommuting or even including such a category.

The studies included in the category cover the topic of the potential pros and cons of virtual work and the challenges related to the coexistence between material and virtual work (Robey et al., 2003). Furthermore, they included elements referring to the workers' characteristics, and the organizations' actions were analyzed to understand how the implementation of virtual working can be more effective both in terms of workers' (teleworkers and other workers) well-being and in terms of organizational performance (Raghuram, 2001). Finally, one article focused on global virtual work deals with topics at least partially overlapping with those analyzed by literature of multicultural organizations.

Due to the growth in virtual work literature and its position as a meta-category, this research stream's theoretical and empirical development is still unclear. Thus, we suggest that future research efforts should discard this research stream. As Raghuram et al. (2019) examined virtual work under the lens of different dimensions of virtuality, we believe there is potential for further research in this area. In terms of virtuality and related technologies, it is possible to elaborate various effects, e.g., augmented reality, holograms, and the metaverse, on an individual and team level. This would contribute to research on different work arrangements and help to develop a theory about antecedents and outcomes.

Distributed workWe analyzed 13 distributed work papers: one conceptual, six qualitative, and six quantitative articles. As the term distributed work was coined quite some time ago, research in the field draws upon a common ground when defining the generalist phenomenon. All conceptualizations and definitions include spatial dispersion at their core. Such dispersion is often related to single team members or complete teams of an organization. Possible variants exist, including a mix of co-located and remote members. However, such relations can also be inter-organizational (Venkatesh & Vitalari, 1992). How dispersion changes over time (e.g., changing worksites (Pritchard & Symon, 2014) or changing between home and company premises (Sia et al., 2004)) differs between articles.

The second common characteristic is facilitating distributed work through ICT. In this context, the conceptualizations also explicitly include the interaction between the entities. More recent studies closely relate to or interchangeably use the term "virtual teams" for distributed teams and distributed work, e.g., Lai and Burchell (2008). Additional aspects mentioned in two or more publications are a possible temporal dispersion, e.g., Vlaar et al. (2008), or remote entities' increased autonomy (Rockmann & Pratt, 2015).

The articles included in our study indicate several developments. While Venkatesh and Vitalari (1992) addressed distributed work as a possibility for additional work from home, al., and Johnson (1999) Correct: Burke et al. (1999)"?>Burke et al. (1999) indicated a rising relevance of distributed teams. The field addressed a well-established phenomenon from the beginning of the new millennium onwards. While the earlier works dealt with distributed work at a team and organizational level (e.g., Sia et al., 2004), the later contributions more often focused on the individual level effects (e.g., Sarker & Sahay, 2010).

On the one hand, we recommend following up on the research of Rockmann and Pratt (2015) on the effects of distributed work on permanent on-site organizational members and team members visiting the office irregularly. The developments connected to COVID-19 indeed will have affected the perception of isolation at the office. On the other hand, research on the cooperation of onshore, offshore and nearshored teams, thus deepening the insights of al., and Oshri (2020) Correct: Brooks et al. (2020)"?>Brooks et al. (2020), poses a promising pathway for future research on distributed work.

Mobile workThe analysis of the category of mobile work included ten articles: one conceptual article, six qualitative, and three quantitative studies, all published between 2007 and 2022.

Definitions of mobile work comprise several facets, such as mobility at work, mobility for work, and working while mobile (Cohen, 2010). Cohen (2010) described mobility as work as the movement of people, goods, or vehicles between places, common in professions such as cycle couriers, truck drivers, and pilots. Moreover, professions that require mobility to accomplish one's job belong to mobility for work, such as district managers, plumbers, and construction workers. In addition, authors use the expressions working while mobile (Cohen, 2010) and mobile work (Brodt & Verburg, 2007; Karanasios & Allen, 2014; Yuan et al., 2010) to express collaborative and independent work activities that can be carried out while mobile or at multiple sites. al., and Neirotti (2015) Correct: Raguseo et al. (2015)"?> Raguseo et al. (2015) adapt al., and Maynard (2004) Correct: Martins et al. (2004) "?>Martins et al. (2004) defined and described mobile work in terms of temporary activities that are accomplished outside the firm's premises and across locational, temporal, and contextual boundaries when being in physical movement. Therefore, mobile technologies such as ICTs support mobile work (Brodt & Verburg, 2007; Raguseo et al., 2015).

Researchers started to explore mobile work from the perspective of enablers, drivers, and barriers for successfully introducing mobile work initiatives with qualitative approaches (Brodt & Verburg, 2007; Cohen, 2010). For example, Yuan et al. (2010) examined mobile work by creating a research model focusing on the fit between task characteristics and mobile work support functions. In addition, this research focused on employees' experiences, willingness to use mobile working, and its implications for home and work domains (Karanasios & Allen, 2014; Porter & van den Hooff, 2020; Raguseo et al., 2015). Additionally, Tranvik and Bråten (2017) investigated mobile work from the perspective of internal systems for governance and control regarding employees' data protection and privacy.

As a missing shared terminology characterizes mobile work, further research could be helpful in defining the research domain clearly and understanding that research stream better.

New ways of workArticles on new ways of work analyzed changes in how work is carried out. According to Aroles et al. (2021), changes can be grouped into three aggregates: firstly, changes related to the introduction of new technologies; secondly, changes impacting the place and the time the activities are carried out, and finally, changes modifying the relation between firms and workers. The category included seven papers, one conceptual article, three qualitative studies, and three quantitative studies. Except for one, which dated to 2013, all the others appeared in the last five years.

Common elements of new ways of work conceptualizations are the role of new technologies and the flexibility in the time and space of carrying out work. Some contributions also pointed out that new ways of work allow workers more control over the tools and content of their work, including a greater degree of freedom in organizing and prioritizing their activities. Workers' access to firm knowledge and spaces was also analyzed (Gerards et al., 2018).

Empirical papers included in the category first analyzed the potential impact of new ways of work, considered in their multiple facets, on employees' informal learning, work engagement, and entrepreneurial behavior (Gerards et al., 2021). Two case studies analyzed the effects of new ways of work implementation; in particular, one investigated changes in managerial behavior aiming to define and reaffirm managers' role in the new work setting (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, 2021).

Smart workSmart work included only three papers published between 2016 and 2021. We excluded other works on the topic due to pre-defined filters. Key points of smart work definitions are the space and time flexibility together with the use of ICT. They did not diverge significantly from the ones highlighted for other categories analyzed in this paper. Under this perspective, the expression smart work seems mainly to be a language variant of other terms more broadly used in professional environments and academic works.

Nevertheless, Malik et al. (2016) conceptualized smart work as a "means of achieving better stakeholder outcomes through new ICT, collaborative, creative and iterative processes of exploration and exploitation of existing and new knowledge" (pp. 1043–1044), emphasizing the role of new knowledge creation and exploitation processes in improving stakeholder satisfaction.

First among the topics analyzed by the papers included in the category was the employees' evaluation of their smart working experience (Cellini et al., 2021). Secondly, the articles analyzed individual and organizational factors impacting employees' attitudes toward smart working, including task performance and job satisfaction (Ko et al., 2021). Finally, researchers investigated the elements influencing attitudes toward smart work hubs and the intensity of their use (Malik et al., 2016).

Regarding future research efforts, scholars should consider a more comprehensive range of context variables. Extending the analysis to a broader range of national contexts to capture the impact of country-specific peculiarities such as culture, technology diffusion, and legislation would improve understanding of the investigated phenomena.

Home officeHome office refers to their homes being the employees' primary work venue to complete their assigned tasks. Researchers describe home office as an intense form of home-based telecommuting in which employees remain in their home and use a virtual connection to the employer in terms of a personal computer and a modem's connection to a telephone line and the employer's computing facility (Hill et al., 2003).

As we see, the interconnectedness of the streams of home office and telecommuting is also supported by al., and Maniam (1998) Correct: Tunyaplin et al. (1998)"?>Tunyaplin et al. (1998) "workplace of the future […] enabled through the concept of telecommuting and the personal computer" (p.178). However, in recognition of this complex definition, it holds the potential to cause additional obscureness.

Hill et al. (2003) investigated the effect of home office on aspects of work such as job performance, job motivation, job retention, and the effect of home office on personal and family life. Along with COVID-19, Primecz (2022) explored home office by discovering the impact of restrictions connected to the pandemic on the work and life of international professional women with children. The emergence of these topics is not unique to the stream on home office. Indeed, one can find their relevance in almost all the fields we probed, stressing the need for an overarching perspective even more.

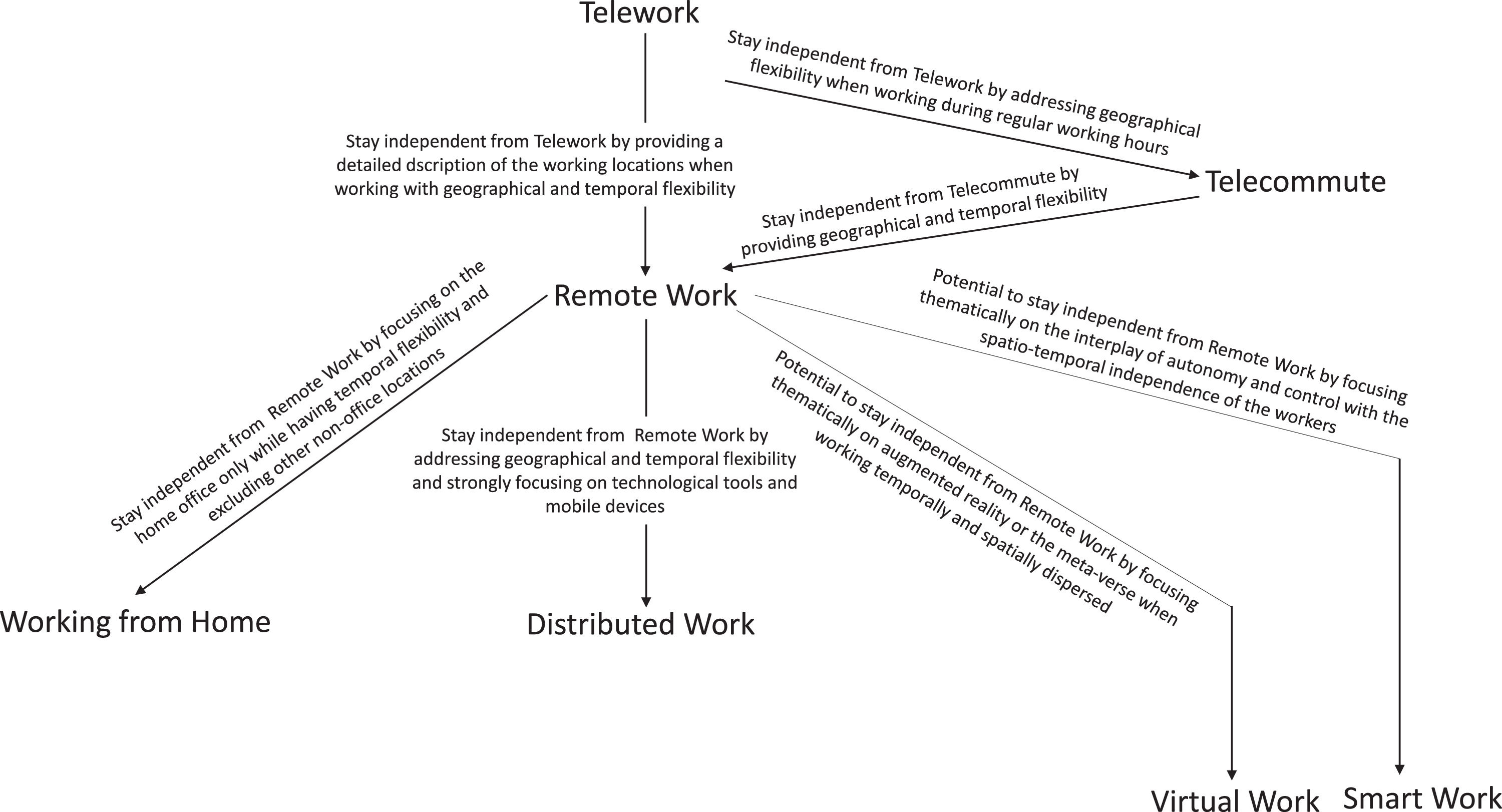

Integrative results: Looking at the maze from above – commonalities, differences, and dead endsResearchers associate telework with geographical and temporal flexibility, enabling employees to use home‐based teleworking, remote offices, and mobile working anytime (Chung & van der Horst, 2018). Further, the role of employment relations between employees and their employer is well recognized in shaping telework, and thus, researchers differentiate between employed teleworkers, self-employed teleworkers, full-time teleworkers, and part-time teleworkers (Baines, 2002). In addition, we noted the role of gender and work-family interdependencies as characteristics of telework (Gálvez et al., 2020).

Research on future of work also addresses the employees' geographical and temporal flexibility to conduct their work; the key is providing employees the choice to work when and where they are most effective. Thus, future of work literature focuses more on technology enabling effective working than telework (Khanna & New, 2008).

Telecommuting literature refers to using telecommunication technologies to perform all or part of one's work during regular working hours outside the organization's physical boundaries (Mayo et al., 2009; Olszewski & Mokhtarian, 1994). Employment relations between employees and their employers connect telecommuting and telework. Nevertheless, in contrast to telework, telecommuting focuses on employees' geographical rather than temporal flexibility. Thus, telecommute is connected to remote work, as employees can conduct work from remote workplaces (Masuda et al., 2017).

Although these two research streams differ in their focus of investigation, they are quite similar at the theoretical level. Besides the closeness of the concepts telework and remote work, the results of our analysis revealed that remote work differs from telework as employees' professional duties receive more attention (Delany, 2021). Consistent with this, remote work specifies if employees' tasks can be performed outside the company's offices, e.g., by accessing the internet and communication systems (Chatterjee et al., 2022).

Furthermore, researchers describe geographical flexibility in telework instead on a "macro level" and go more into detail when focusing on flexibility regarding the working location provided by remote work (Barsness et al., 2005). Based on logic, remote work includes working from home as a working location. The same holds for home office as a non-office location connected through ICT while experiencing temporal flexibility (Chi et al., 2021). Distributed work is a facet of remote work, as it involves collaboration among teams in remote locations across locational, temporal, and relational boundaries (Venkatesh & Vitalari, 1992; Vlaar et al., 2008). In this context, distributed work is characterized by collaboration and communication among team members, especially in virtual teams (e.g., Lai & Burchell, 2008).

Furthermore, distributed work from a contextual viewpoint is partially connected to working from home, as employees work at sites intentionally located near the employees' homes and work at least part of the time at home (Lai & Burchell, 2008). Using mobile work, employees can accomplish tasks across locational, temporal, and contextual boundaries (Chatterjee et al., 2022); thus, it can be understood as a facet of distributed work as it is defined via physical movement from one place to another (Yuan et al., 2010) and focuses strongly on mobile devices (Jo & Lee, 2022). Consistent with the rise of mobile devices, innovations in mobile settings characterize mobile work (Kietzmann, 2008).

Virtual work is temporally and spatially dispersed and described as working remotely (Raghuram, 2001; Robey et al., 2003). In its current use, it represents a sub-category of remote work. While similar to distributed work, researchers put virtual work in a more global context characterized by coworkers collaborating across different countries (Nurmi & Hinds, 2016). Smart work poses another generic facet of remote work by providing employees with maximum geographical and temporal flexibility and autonomy (Raghuram, 2001).

New ways of work also represent a sub-category of remote work, as employees can use geographical and temporal flexibility while having control over the work content and having access to organizational knowledge (Aroles et al., 2021). Further, the firm adopts new technological tools and strategies, e.g., hot desking and mobile work (Assarlind et al., 2013; Kingma, 2019). This also directly connects new ways of work to mobile work.

On the other hand, new work is not directly connected to any category because researchers describe new work practices and attributes as team-based work, job rotation and communication, job autonomy, and meaningfulness (Ollo-Lopez et al., 2010; Schmitz et al., 2021). We depicted these connections in Figure 2.

The future of scientific work? Leximancer's view on the state of the art1To validate our qualitative mapping of the research streams and enrich our results, we turned to the analysis of the streams' literature through Leximancer. The concept map provided by the software identified 78 constructs and nine themes for the overall analysis of the articles. The map is depicted in Figure 3.

The theme >employees< stands at the center of the map, pointing to related concepts such as working times, hours, and flexibility. The theme overlaps with the second central theme, >organization<. The overlap includes concepts such as 'individuals,’ 'relationships,’ 'roles,' and 'managers,' but also 'control' and the 'workplace', concepts constituting and defining memberships of individuals in organizations. The >organization< theme mirrors this; it includes concepts such as 'people,’ 'human,' and 'organizational.' Connecting 'social issues' and 'management, >organization< establishes a link with the third theme of high relevance, >technology<. Their overlap here addresses change, a concept also touching the communication theme (rated sixth most relevant by Leximancer). The >technology< theme not only addresses the expected concepts such as 'digital' or 'information' but also 'power,’ 'processes,’ 'knowledge,' and especially 'business,' indicating how central technology has become for these topics.

The two research fields that emerge as themes, >telework< (driven by related sub-concepts) and >telecommute< (including 'performance', 'quality' but also 'psychological' as concepts), Leximancer stably situated on opposite sides of the map, representing their disparity compared to the other included themes. We attributed this location to their parallel development over time and the fact that telecommuting is a narrower sub-category of telework.

Our review field, mobile work, drove the theme >mobile<, the only concept beside itself being innovation; neither field nor theme were closely connected besides an overlap with technology (required for mobile work). The theme >employment< (purposely not merged with employees before) features macro 'economic' concepts such as 'labor,' 'employment,' and 'public' and 'policy.' The centrality of 'firms' in this theme indicates the close connection to operational issues. Finally, the theme >women< is of importance, as its significant overlap with >employees< features work-family-conflict concepts 'family,' 'balance' 'life,' 'stress,' and 'balance.' While Leximancer rates the theme as less essential, the substantial overlap with the employee theme, a split concept 'home,' and the above concepts represent its importance. However, it is not connected directly to any of our research fields, whose positioning and connections we addressed in the next step.

As we tagged the articles according to their field and these appeared on the map (red text outside of the clouds), Leximancer offered us a rich insight into the different fields and their connection.

As with the themes, the opposing positioning of the telecommute and telework fields is of interest to us. Telework with 12300 hits over all documents poses a distinctive but overreaching concept. Its direct connection to the >employee< theme (via 'home') and >employment< indicates its generic nature. The link to 'home' is important, as it establishes the direct connection with the fields working from home and home office. With a 12% probability of co-occurrence with telecommuting, telework still encloses the related field.

On the other hand, telecommuting is rather specific and closely connected to the field of remote work, which in turn belongs to the >telecommuting< theme.

A comparably close relationship exists between distributed work and virtual work: both are related to 'teams,' 'members,' and 'communication,' showing their strong relationship. However, distributed work addresses a more differentiated number of concepts than virtual work.

While new work and new ways of work are directly coupled via the 'process' concept of the >technology< theme and thus co-located, the number of overlapping concepts between new work and future of work is significant. Still, future of work, while a smaller research field than telework, overarches most of the concepts on the map, representing its generic nature.

The concept map generated by Leximancer supports several of our previously stated conceptual foci, commonalities, and differences between the research streams. With this successful form of triangulation described by Lemon and Hayes (2020), we can derive further research avenues.

Contribution: Leaving the maze – where to next?The future of work and its related research fields exhibit a maze in which many scholars have gotten lost before. We started with the aim not only to provide a map but also to tear down the walls of this maze, a process that profoundly changes the design of the labyrinth. This step also challenges the former and current constructors to help reduce the complexity and develop clear pathways for our research field rather than rebuilding the maze. It is not our intent to diminish the achievements of other scholars researching developments in the wider field. On the contrary, we argue that placing their essential work in a more clearly defined context enhances their contribution to the discourse and increases the overall progress of research. Thus, we propose several future developments and directions:

Concerning the topic future of work, and the category of new work, we recommend caution concerning their meaning in an ever-developing field. Technological advancements, societal changes, and economic developments are ongoing with no clear starting point and no defined end. Moving forward, the future of work may look different, as the early papers on telecommuting show. However, the missing temporal reference points are neither the biggest nor the only problem. Their generic, underdefined conceptualization makes both categories appear like empty hulls, which authors can and do load with any content they feel suitable. We believe that such a category will neither lead to a common understanding nor a definition, nor will it enable progress in this field.

Furthermore, we fear that ambiguous fields will hamper the progress of other fields, as bridging between them could become obfuscated through those additional categories, further decreasing their added value.

This issue partially holds for virtual work and smart work. However, we believe that virtual work can still be coined more specifically and evolve into a separate, promising field. Considering rarely mentioned developments, such as augmented reality or the meta-verse, we envision that such topics being a valuable direction for virtual work to follow. As for smart work, the field needs to free itself from remote work. We propose that researchers do so by scrutinizing more closely the interplay of autonomy and control with the spatial-temporal independence of the workers. Another possibility lies in focusing on the interplay of dimensions involved, e.g., the concept of Bricks, Bytes, and Behaviour (Kok, 2016).

Further vagueness comes to light when comparing new ways of work and mobile work, as both categories offer employees geographical and temporal flexibility while relying strongly on mobile devices and technological tools (Assarlind et al., 2013; Jo & Lee, 2022). As the categories new ways of work and mobile work are sub-categories of distributed work, we propose homogenizing the research streams and relating them to distributed work. Leximancer results support this proposal because of clear thematical overlaps between new ways of work, mobile work, and distributed work. Regarding distributed work, this category should be maintained independently of remote work by addressing geographical and temporal flexibility and strongly focusing on technological tools and mobile devices.

While working from home and home office offer temporal flexibility without switching between more remote working locations, these categories are strongly connected (Chi et al., 2021). In addition, the thematical overlap of both categories becomes apparent in Leximancer. Thus, we propose homogenizing the research streams of working from home and home office. At the same time, working from home should focus on this location only while having temporal flexibility. Excluding other non-office locations distinguishes it from concepts such as remote work.

For future research, we propose restricting ourselves to the categories telework, telecommute, remote work, distributed work, working from home, virtual work, and smart work, as we can drive clear differentiations between them. We depicted these categories and their distinctions in Figure 4. The older categories (e.g., telework, telecommute, or remote work) are well-researched conceptually and empirically, especially the newer categories (such as smart work or virtual work) still lack research. Regarding the overall field, scholars should consider a broader range of context variables for further research. We recommend research that investigates more specific dimensions of the ongoing increase in the virtuality of different work arrangements. Therefore, it is essential to directly incorporate dimensions such as, e.g., augmented reality, virtual reality, and metaverse to understand better the influence of the ongoing digitalization on different work arrangements, on an individual and team level.

As our study has primarily focused on clearing the terminology, future research may want to focus on discussing when to adapt each of the categories mentioned above. The categories are different in their meaning and effective for specific types of work, distinct situations, and certain types of employees. The field would benefit from examining these specific cases.

Conclusion: What to take from the mazeWith our article, we set out to identify relevant research streams focusing on the development of the working world and somewhat connected to the term future of work. We identified twelve research streams related to the future of work through an iterative design, covering well-established and emerging fields. We characterized the development of each of the streams separately, pointing out inconsistencies, strengths, unique approaches, and possible developments for each stream.

During the second phase, we addressed the often-parallel evolution of the twelve fields, mapping the development of often related and partially redundant topics within the streams presently existing. We thus provided an overview of which streams scholars and practitioners interested in the developments of work arrangements can turn to for relevant information and where to expect co-existing yet isolated research.

We believe that the most significant contribution of this article lies in its proposal to establish a higher concept clarity. We propose to do so by merging research streams (e.g., working from home and home office), clearly dedicating streams to unique topics (e.g., virtual work to research on augmented reality or the metaverse), and discontinuing the use of catch-all terms like new work but also more established, yet equally ambiguous streams like future of work. Through the first step we became aware of the tremendous amount of relevant information 'buried' in these indistinct fields. Thus, discontinuing or merging streams does not devalue their research but makes future publications more accessible for scholars and practitioners. As new buzzwords lead to the emergence of supposedly new streams (e.g., hybrid work), keeping a parsimonious terminology leading to a focused exchange and progress will be an ongoing challenge.

While we are aware of the irony of our argument to discontinue the exact stream we have augmented, we hope that fellow scholars agree with us and frame their research under more precise concepts.

Our article also allows practitioners and policymakers to access fellow researchers' works more efficiently. By reducing the number of parallel research streams and discontinuing those with catch-all terms, it will become easier to identify those works and researchers that can help with specific challenges. At the same time, reducing uncertainty will allow researchers to explain new research results to practitioners by precisely explaining their objectives.

LimitationsWhile we have contributed to the state and future development of the named fields through rigorous research, our paper underlies limitations inherent in literature reviews. The emergence of alleged new fields and topics has gained substantial momentum. Even though we adapted and extended the search terms during the search process, we are aware that we may have missed related fields or new fields that have arisen even while we were completing our analysis. This potential weakness demonstrates the necessity to reframe and sharpen our far-spread research to create shared insights for academia and praxis. The analysis process of large amounts of literature, aligning insights, is prone to subjective influences, even when keeping to the RAMSES methodology. By drawing upon Leximancer for triangulation, we attempted to mitigate this risk (Lemon & Hayes, 2020).

This work was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund provided by the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.