This review aims to summarize evolving evidence on topical steroid (TS) therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Currently, we still use “off-label” TS, originally designed for bronchial or intranasal delivery. Direct oral administration (i.e., oral viscous budesonide) achieves better histological results than the aerosolized swallowed route, due to longer mucosal contact time. High-dose fluticasone (880μg bid) has recently shown higher cure rates in children and adults. Steroid resistance is present in around 25–40% of patients. Nonetheless, novel steroid formulations specifically designed for EoE have exhibited outstanding preliminary results (cure rates around 100%). Narrow caliber esophagus (<13mm) might explain persistent dysphagia despite histological remission on TS therapy and endoscopic dilation should be considered. TS are currently considered safe drugs, but we lack long-term safety data. Maintenance anti-inflammatory therapy is recommended in all patients to prevent disease recurrence and esophageal fibrotic remodeling, although this strategy is yet to be defined.

Este artículo de revisión pretende aglutinar la creciente evidencia científica en torno al uso de corticoides tópicos en la esofagitis eosinofílica (EEo). No disponemos aún de corticoides diseñados específicamente para la EEo, por lo que seguimos «tomando prestados» los corticoides que se administran en el asma o la rinitis alérgica. La administración oral directa del corticoide (p. ej., soluciones viscosas) consigue tasas de curación histológica superiores a la deglución del corticoide tras su pulverización desde un aerosol, debido a un tiempo de contacto con la mucosa más prolongado. El uso de dosis altas de fluticasona (880mcg/12h)ha demostrado recientemente tasas de curación superiores en niños y adultos. El 25–40% de los pacientes con EEo no consiguen la remisión histológica con los corticoides disponibles en la actualidad. Sin embargo, existen datos preliminares prometedores, con una curación histológica cercana al 100%, con nuevas formulaciones (soluciones viscosas, tabletas efervescentes) específicamente diseñadas para la EEo. La persistencia de disfagia pese a la curación de la mucosa en tratamiento con corticoides puede ser explicada por la existencia de un caliber esofágico disminuido (<13mm) y se debe considerar la dilatación endoscópica, incluso sin estenosis evidentes. Pese a que los corticoides tópicos son considerados fármacos seguros, actualmente carecemos de datos de seguridad a largo plazo. Las guías clínicas recomiendan tratamiento de mantenimiento en todos los pacientes para prevenir la recurrencia de la inflamación y el desarrollo ulterior de estenosis esofágica, si bien la estrategia a seguir a largo plazo no está bien definida aún.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated esophageal disease, defined clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction, histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation and showing unresponsiveness to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.1 Since the first descriptions in the early 1990s,2,3 it has become an emerging cause of esophageal symptoms all over the world, being currently the second cause of esophageal inflammation after gastro-esophageal reflux disease and the leading cause of dysphagia and food impaction in children and young adults. Furthermore, its incidence has steadily risen4 and consistent prevalence rates have been recently reported in Europe and the USA, ranging from 44 to 56 cases per 100,000 inhabitants,5 comparable to that of Crohn's disease in western countries.

The natural history of EoE has become more defined in the last few years. It is a chronic disorder, with persistent symptoms, endoscopic features and esophageal eosinophilia over time, significantly reducing the health-related quality of life (QoL) of affected individuals. In the absence of treatment, esophageal inflammation in children progresses to fibrostenotic remodeling of the esophagus in the adulthood. Two recent retrospective studies have pointed out this very natural history of the disease. While the first reported that the odds of having a fibrostenotic EoE phenotype more than doubled for every 10-year increase in age,5 the second demonstrated that the duration of untreated disease directly correlates with the prevalence of esophageal strictures in a time-dependent manner over a 20-year follow-up period,6 in a similar way to that demonstrated in the natural history of Crohn's disease. To date, no malignant potential has been associated with this disease.

Treatment of EoE is based on its pathogenesis. EoE is believed to be a Th2 cell-mediated immune response (involving interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-13) to food and/or environmental allergens. IL-5 and IL-13 stimulate the esophageal epithelium to produce eotaxin 3, a potent chemokine that recruits eosinophils toward the esophagus.7 Activated eosinophils release multiple factors that promote local inflammation and tissue injury, including transforming growth factor β (TGF-β1). TGF-β1, along with mast cells, seems to be key mediators for esophageal remodeling, resulting in subepithelial fibrosis and smooth muscle dysfunction.8

There are three major treatment approaches to EoE, often referred to as the 3 Ds: drugs, diet, and dilation. Currently, the most reliable therapeutic targets are histological remission and resolution of caliber abnormalities. Drugs and dietary changes target eosinophilia inflammation and where applicable, they should be combined with dilation, that targets esophageal remodeling and fibrotic complications, but does not influence underlying inflammation.9 Choice of treatment depends on patients’ clinical features, patient and provider preferences, local expertise, and costs. Maintenance anti-inflammatory therapy is necessary in all patients to avoid disease recurrence, prevent esophageal fibrotic remodeling and stricture formation.

Currently, no drug therapy has been approved by regulatory authorities, even though swallowed topical corticosteroids are highly efficient in treating active EoE.10 The aim of this review is to summarize evolving evidence on pharmacological therapy available for EoE, specifically focusing on corticosteroids as the cornerstone pharmacological therapy for short- and long-term management of the disease. Few studies with other steroids (ciclesonide) experimental drugs (immunomodulators, montelukast, CRTH2 antagonists – OC000459, omalizumab, anti-TNFα, anti IL-5 and anti IL-13 antibodies) are described elsewhere11 and have obtained notably worse clinical results than topical steroids, so they should be currently considered as rescue therapies in refractory patients unresponsive to corticosteroids, dietary and endoscopic intervention.

Topical steroid therapyThe best studied medications are fluticasone, dispensed from a metered-dose inhaler, and budesonide, administered either as a viscous slurry or as a swallowed nebulized vapor. In a multitude of studies, both drugs have demonstrated efficacy in treating EoE.12–31 Due to lack of approved drugs for EoE, we are still using “off-label” drugs, designed for other allergic diseases, such as asthma or rhinitis. As for inhalers, the medication, without the use of a spacer, is usually puffed into the mouth twice daily during a breath hold, and then swallowed, with a minimum amount of water to minimize pulmonary deposition and risk for candidiasis. A liquid formulation of fluticasone designed for intranasal delivery (nasal drops) might be a valid alternative as well, which just need to be swallowed. Oral viscous budesonide preparation consists of mixing this medication with multiple packets of sucralose (usually 3–5mg of sucralose are required per 2mL of aqueous budesonide to achieve the desired thickened consistency) to make a viscous solution that is swallowed twice daily.9 For all topical steroids, administration should be after meals, and patients should not eat or drink anything for 30–60min after swallowing the drug.

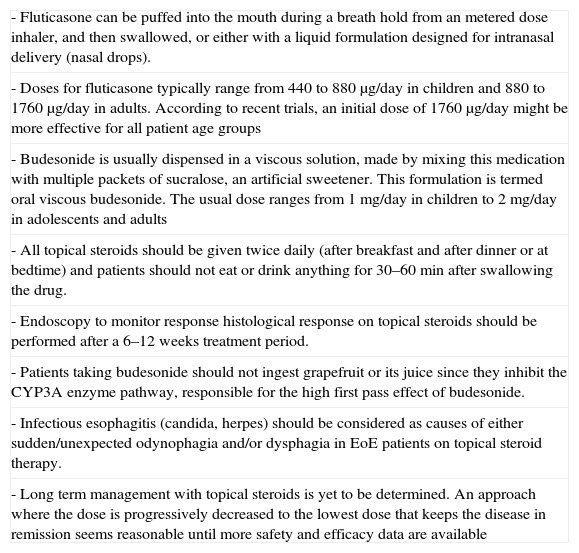

Doses for fluticasone typically range from 440 to 880μg/day in children and 880–1760μg/day in adults. Findings from the two most recent placebo-controlled fluticasone trials indicate that an initial dose of 1760μg/day might be optimal for all patient age groups.19,23 The usual dose of budesonide ranges from 1mg/day in children to 2mg/day in adolescents and adults. All of these practical considerations are summarized in Table 1.

Considerations for use of topical steroids in clinical practice.

| - Fluticasone can be puffed into the mouth during a breath hold from an metered dose inhaler, and then swallowed, or either with a liquid formulation designed for intranasal delivery (nasal drops). |

| - Doses for fluticasone typically range from 440 to 880μg/day in children and 880 to 1760μg/day in adults. According to recent trials, an initial dose of 1760μg/day might be more effective for all patient age groups |

| - Budesonide is usually dispensed in a viscous solution, made by mixing this medication with multiple packets of sucralose, an artificial sweetener. This formulation is termed oral viscous budesonide. The usual dose ranges from 1mg/day in children to 2mg/day in adolescents and adults |

| - All topical steroids should be given twice daily (after breakfast and after dinner or at bedtime) and patients should not eat or drink anything for 30–60min after swallowing the drug. |

| - Endoscopy to monitor response histological response on topical steroids should be performed after a 6–12 weeks treatment period. |

| - Patients taking budesonide should not ingest grapefruit or its juice since they inhibit the CYP3A enzyme pathway, responsible for the high first pass effect of budesonide. |

| - Infectious esophagitis (candida, herpes) should be considered as causes of either sudden/unexpected odynophagia and/or dysphagia in EoE patients on topical steroid therapy. |

| - Long term management with topical steroids is yet to be determined. An approach where the dose is progressively decreased to the lowest dose that keeps the disease in remission seems reasonable until more safety and efficacy data are available |

Ciclesonide, a relatively new inhaled, metered-dose administered corticosteroid used for asthma and allergic rhinitis, has also recently been added to the pharmacological arsenal for treating EoE.32 Ciclesonide is a pro-drug that becomes active after being converted by esterases from the esophageal epithelial cells. It presents a much higher glucocorticoid receptor binding (up to 100 times greater) than fluticasone and budesonide, and a low systemic bioavailability due to a high first-pass hepatic metabolism. These characteristics provide ciclesonide with potential advantages in terms of higher pharmacological potency and lower systemic side effects. Two small series consisting of four children each, some of them with loss of response to other topic steroids, documented histological remission rates of 100% and 50%, respectively.32,33 Further research will determine the potential role of ciclesonide in clinical practice.

Intimate mechanisms of action for topical steroids in EoETopic steroids exert local anti-inflammatory effects in the esophagus through several mechanisms, including esophageal induction of the steroid-responsiveness FK506-binding protein 5 (FKBP51) gene expression34 and that of microRNA miR-645.35 Transcriptional inhibition of specific promoter response elements, destabilization of cytokine mRNA and direct induction of cellular apoptosis are other recognized mechanisms of action. As a consequence, the ability of topic steroids to reverse EoE has been repeatedly demonstrated at a gene expression and molecular level.36,37 Swallowed steroid therapy directly acts over gene regulation in esophageal epithelial cells (which are a major source of eotaxin-3), where they repress IL-13-induced eotaxin-3 expression.37

Swallowed topical steroids can also reverse esophageal fibrotic remodeling. Response to budesonide in children with EoE was associated with reversion of esophageal fibrous remodeling, related to a reduction in TGF-β and pSmad 2/3-positive cells and decreased expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, a marker of vascular activation.38 In contrast, collagen deposition in the lamina propia of adult EoE patients was not reduced significantly after 1 year of fluticasone treatment, despite downregulation profibrogenic cytokines gene expression levels.39 A limited ability for topically administered drugs in penetrating to deep esophageal layers to act over the inflammatory infiltrate at this location has been argued as an explanation, due to the persistence of eosinophilic infiltration in the lamina propria of a subgroup of EoE patients, despite reversion of the epithelial EoE features.39

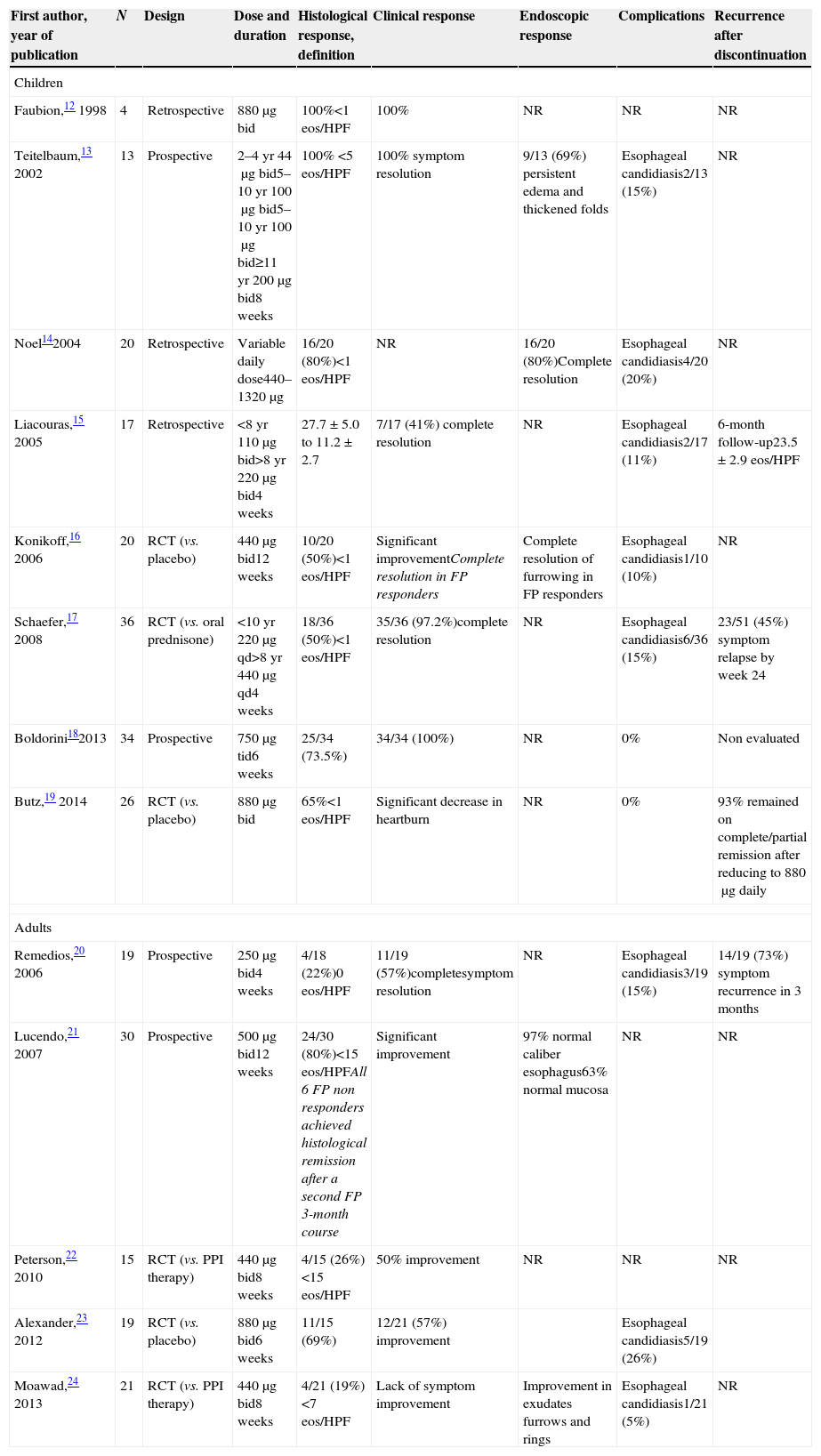

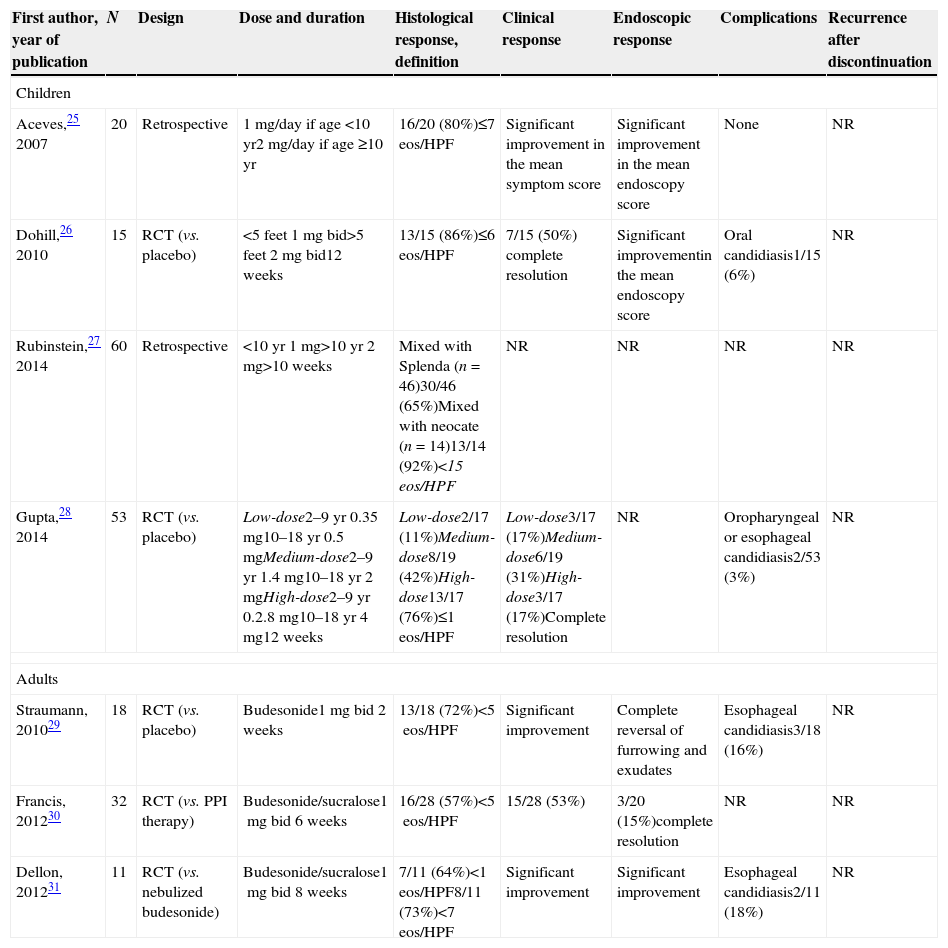

Different therapeutic targets, drugs, vehicles and doses: what can we infer from randomized trials and prospective studies on topical steroids?Histological remission, defined by variable thresholds (<1, <5, <7, <10 and <15eos/HPF, >90% decrease in mean eosinophil count) has been the gold standard to evaluate a response after topical corticosteroids. Furthermore, different drugs (fluticasone and budesonide), different vehicles (aerosolized swallowed fluticasone and oral budesonide), a wide range of doses (fluticasone: children (220–1760μg daily), adults (500–1760μg daily); budesonide: children (0.35–4mg daily)) and last, but not least, different duration of therapy (from 2 to 12 weeks) have been reported in trials on topical steroids.12–31 All of these data in studies using fluticasone and budesonide, in both children and adults, are displayed in Tables 2 and 3. Therefore, interpretation of these data should be carried out carefully, albeit we can draw some straightforward conclusions from the studies conducted over the past 15 years:

- -

Histological remission rates with high-dose fluticasone (1000–1760μg/day) are higher than those with low-dose fluticasone (≤880μg/day), in both children and adults (see Table 2).

- -

Histological remission rates with budesonide are consistent in children and adults (usually above 60% efficacy) with more standardized doses (see Table 3).

Main results of studies evaluating the efficacy of swallowed fluticasone propionate for EoE, in both children and adults.

| First author, year of publication | N | Design | Dose and duration | Histological response, definition | Clinical response | Endoscopic response | Complications | Recurrence after discontinuation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | ||||||||

| Faubion,12 1998 | 4 | Retrospective | 880μg bid | 100%<1 eos/HPF | 100% | NR | NR | NR |

| Teitelbaum,13 2002 | 13 | Prospective | 2–4yr 44μg bid5–10yr 100μg bid5–10yr 100μg bid≥11yr 200μg bid8 weeks | 100% <5eos/HPF | 100% symptom resolution | 9/13 (69%) persistent edema and thickened folds | Esophageal candidiasis2/13 (15%) | NR |

| Noel142004 | 20 | Retrospective | Variable daily dose440–1320μg | 16/20 (80%)<1 eos/HPF | NR | 16/20 (80%)Complete resolution | Esophageal candidiasis4/20 (20%) | NR |

| Liacouras,15 2005 | 17 | Retrospective | <8yr 110μg bid>8yr 220μg bid4 weeks | 27.7±5.0 to 11.2±2.7 | 7/17 (41%) complete resolution | NR | Esophageal candidiasis2/17 (11%) | 6-month follow-up23.5±2.9 eos/HPF |

| Konikoff,16 2006 | 20 | RCT (vs. placebo) | 440μg bid12 weeks | 10/20 (50%)<1 eos/HPF | Significant improvementComplete resolution in FP responders | Complete resolution of furrowing in FP responders | Esophageal candidiasis1/10 (10%) | NR |

| Schaefer,17 2008 | 36 | RCT (vs. oral prednisone) | <10yr 220μg qd>8yr 440μg qd4 weeks | 18/36 (50%)<1 eos/HPF | 35/36 (97.2%)complete resolution | NR | Esophageal candidiasis6/36 (15%) | 23/51 (45%) symptom relapse by week 24 |

| Boldorini182013 | 34 | Prospective | 750μg tid6 weeks | 25/34 (73.5%) | 34/34 (100%) | NR | 0% | Non evaluated |

| Butz,19 2014 | 26 | RCT (vs. placebo) | 880μg bid | 65%<1eos/HPF | Significant decrease in heartburn | NR | 0% | 93% remained on complete/partial remission after reducing to 880μg daily |

| Adults | ||||||||

| Remedios,20 2006 | 19 | Prospective | 250μg bid4 weeks | 4/18 (22%)0eos/HPF | 11/19 (57%)completesymptom resolution | NR | Esophageal candidiasis3/19 (15%) | 14/19 (73%) symptom recurrence in 3 months |

| Lucendo,21 2007 | 30 | Prospective | 500μg bid12 weeks | 24/30 (80%)<15eos/HPFAll 6 FP non responders achieved histological remission after a second FP 3-month course | Significant improvement | 97% normal caliber esophagus63% normal mucosa | NR | NR |

| Peterson,22 2010 | 15 | RCT (vs. PPI therapy) | 440μg bid8 weeks | 4/15 (26%)<15eos/HPF | 50% improvement | NR | NR | NR |

| Alexander,23 2012 | 19 | RCT (vs. placebo) | 880μg bid6 weeks | 11/15 (69%) | 12/21 (57%) improvement | Esophageal candidiasis5/19 (26%) | ||

| Moawad,24 2013 | 21 | RCT (vs. PPI therapy) | 440μg bid8 weeks | 4/21 (19%)<7eos/HPF | Lack of symptom improvement | Improvement in exudates furrows and rings | Esophageal candidiasis1/21 (5%) | NR |

Main results of studies evaluating the efficacy of oral viscous budesonide for EoE, in both children and adults.

| First author, year of publication | N | Design | Dose and duration | Histological response, definition | Clinical response | Endoscopic response | Complications | Recurrence after discontinuation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | ||||||||

| Aceves,25 2007 | 20 | Retrospective | 1mg/day if age <10yr2mg/day if age ≥10yr | 16/20 (80%)≤7 eos/HPF | Significant improvement in the mean symptom score | Significant improvement in the mean endoscopy score | None | NR |

| Dohill,26 2010 | 15 | RCT (vs. placebo) | <5 feet 1mg bid>5 feet 2mg bid12 weeks | 13/15 (86%)≤6 eos/HPF | 7/15 (50%) complete resolution | Significant improvementin the mean endoscopy score | Oral candidiasis1/15 (6%) | NR |

| Rubinstein,27 2014 | 60 | Retrospective | <10yr 1mg>10yr 2mg>10 weeks | Mixed with Splenda (n=46)30/46 (65%)Mixed with neocate (n=14)13/14 (92%)<15 eos/HPF | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Gupta,28 2014 | 53 | RCT (vs. placebo) | Low-dose2–9yr 0.35mg10–18yr 0.5mgMedium-dose2–9yr 1.4mg10–18yr 2mgHigh-dose2–9yr 0.2.8mg10–18yr 4mg12 weeks | Low-dose2/17 (11%)Medium-dose8/19 (42%)High-dose13/17 (76%)≤1eos/HPF | Low-dose3/17 (17%)Medium-dose6/19 (31%)High-dose3/17 (17%)Complete resolution | NR | Oropharyngeal or esophageal candidiasis2/53 (3%) | NR |

| Adults | ||||||||

| Straumann, 201029 | 18 | RCT (vs. placebo) | Budesonide1mg bid 2 weeks | 13/18 (72%)<5eos/HPF | Significant improvement | Complete reversal of furrowing and exudates | Esophageal candidiasis3/18 (16%) | NR |

| Francis, 201230 | 32 | RCT (vs. PPI therapy) | Budesonide/sucralose1mg bid 6 weeks | 16/28 (57%)<5eos/HPF | 15/28 (53%) | 3/20 (15%)complete resolution | NR | NR |

| Dellon, 201231 | 11 | RCT (vs. nebulized budesonide) | Budesonide/sucralose1mg bid 8 weeks | 7/11 (64%)<1eos/HPF8/11 (73%)<7eos/HPF | Significant improvement | Significant improvement | Esophageal candidiasis2/11 (18%) | NR |

Topical medications are usually applied directly to body surfaces, mostly to the skin, but can also be inhalational (i.e., asthma medications) or applied to the surface of tissues other than the skin, such as eye or ear drops. The word topical is derived from the Ancient Greek topos, meaning place or location. As such, topical medications will be effective if they remain in place, ensuring skin or mucosal prolonged contact time.

The esophagus is really a challenge for topical delivery. The flow of esophageal content always takes advantage of gravity, except for the supine position. The esophagus is a mobile organ, made up mostly of smooth muscle showing high-amplitude peristaltic contractions in the distal third of the organ. In addition, constant saliva swallowing, food and drinks and gastroesophageal reflux will likely remove the drug, preventing an effective coating of the mucosa by the drug.

Is the drug delivery method more important than the type of corticosteroid?Presently, we just have one milestone study comparing different formulations of topical steroids. In this randomized trial,31 nebulized and viscous preparations of budesonide 1mg twice daily for 8 weeks were compared in a cohort of adult patients. Study endpoints included dysphagia improvement, reduction in eosinophil counts and mucosal medication contact time, which was measured by nuclear scintigraphy with tagged radiocontrast. The authors found that complete histologic remission was significantly higher in the oral viscous budesonide group than in the swallowed nebulizer solution (64% vs. 27%, p 0.09), although both groups had comparable improvement in their dysphagia scores. Nuclear scintigraphy showed that overall drug mucosal contact time was significantly longer (48,900 vs. 19,200, p 0.005) in patients treated with the oral viscous budesonide than the nebulizer solution and this difference was much higher in the distal esophagus (18,100 vs. 3800, p 0.001). Therefore, this study pointed out that the frequency of histologic improvement was directly related to higher mucosal contact time and has highlighted the importance of appropriate drug delivery methods in the treatment of EoE.

Predictors of steroid-refractory EoEAround 25–40% of patients do not show histological remission after topical steroid therapy. Recent studies have linked steroid resistance to a less severe inflammation of the mucosa,18,40 low-to-medium drug doses,28 stricture requiring baseline dilation40 and genetic variants.19 However, these novel findings might be circumvented with the advent of novel drugs specifically designed for EoE. Preliminary results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial evaluating different novel budesonide formulations have been recently reported.41 Seventy-six patients from 23 European countries were randomized to receive during 2 weeks: (1) budesonide effervescent tablets 2×1mg/day, (2) budesonide effervescent tablets 2×2mg/day, (3) budesonise viscous suspension 2×2mg/day and (4) placebo. While no patient achieved histological remission in the placebo group, histological remission rates in the drug arms (after a 2-week trial) were 100%, 94% and 93%, respectively. This trial was early interrupted due to outstanding results. On account of cure rates close to 100%, this study emphasizes the importance of an specific drug delivery system as the key factor for responsiveness to topical steroids, questioning recently reported predictors of steroid resistance.18,19,28,40

Histological remission without symptomatic response: a common scenario after topical steroidsAs shown in Tables 2 and 3, clinical response to topical steroids is variable and does not always correlate with histological remission. In randomized controlled trials evaluating fluticasone15,18,22 and budesonide,25,27,28 symptom response to topical steroids has been poor and mostly similar to response to placebo.

The absence of a validated symptom assessment instrument for pediatric and adult EoE patients is a major setback for symptom monitoring in EoE trials.10 Complicating this scenario, EoE symptoms typically change from the childhood (failure to thrive, vomiting, abdominal pain, heartburn) to adulthood (dysphagia and food impaction). In addition, the severity of dysphagia in EoE patients is often masked by long-standing behavioral modifications that include avoidance of specific food textures, prolonged meal times and excessive mastication.10 The advent of a recently validated patient-reported outcome assessment tool, which evaluates dysphagia severity according to eight distinct food consistencies and also takes into account behavioral adaptations, may better estimate disease impact and treatment benefits in EoE.42

Therefore, we can draw two major conclusions: (1) symptoms alone are not an accurate tool to monitor response to therapies in EoE and (2) the resolution of EoE extends beyond the mucosal healing of eosinophilic inflammation. In this regard, esophageal reduced distensibility due to diffuse subepithelial fibrosis and remodeling has been recently shown to be a strong predictor for food impaction risk and requirement for esophageal dilation in EoE.43 Furthermore, endoscopists commonly overlook the presence of esophageal luminal compromise in patients with symptomatic esophageal eosinophilia. In a nice recent study,44 58 patients, without impaired passage of a standard diagnostic adult endoscope, were evaluated with a barium swallow. 59% had a narrowed esophageal diameter≤20mm and 47% had a diameter≤13mm, but the most important finding is that endoscopists recognized a narrowed esophagus (≤13mm) and diffuse narrowing (narrowed segment>8cm in length) only 27% and 13% of the time, respectively. Seven patients on histological remission gained symptom improvement after endoscopic dilation. Another similar study raised the usefulness of endoscopic dilation with a novel balloon pull-through technique to size and dilate the esophagus in EoE.45 Similarly, resistance was encountered in 11/13 symptomatic patients (85%), even though no narrowing was initially visualized on endoscopy. Esophageal tears and improvement of dysphagia were reported in 9/11 patients.

Safety concernsTopical steroid therapy, either with fluticasone or budesonide, is felt to be safe in general, since they lack complications seen with systemic steroids. Candida esophagitis has been reported in 5–30% of cases, with many being noted incidentally during follow-up endoscopy.1 Herpes esophagitis, with and without topical steroid use, has been lately reported in EoE patients.46,47 These complications should be sought in EoE patients with sudden unexpected dysphagia and/or odynophagia. To date, there has been no evidence of adrenal suppression up to 2 months of treatment. Long-term safety data are not yet available for growth rates or bone density, which are major concerns in children.

Long-term management with topical steroidsWhen treatment is stopped EoE typically recurs,9,10 raising questions about whether treatment should be continued for all patients. The most recent guidelines1 recommend considering maintenance treatment for all patients with EoE – particularly for those with severe or rapidly relapsing symptoms, history of food impaction, strictures that require dilation, or history of esophageal perforation. While a patient successfully treated with dietary elimination and food triggers have been identified, ongoing elimination of the dietary elements should be used as maintenance therapy, whether topical steroids should be continued indefinitely is controversial, particularly in light of the potential side effects and lack of long-term data.48

An approach where the dose is progressively decreased to the lowest dose that keeps the disease in remission seems reasonable until more data are available.48 The effectiveness of this approach has been confirmed in two recent randomized, placebo-controlled trials. In this first study, 28 EoE adults previously brought into remission with budesonide were randomized to receive low-dose maintenance budesonide (0.25mg bid) or placebo for a 50-week period.49 Low-dose budesonide was able to maintain a complete histologic remission (<5 mean eosinophils/HPF) in 35.7%, while no patients in the placebo group remained in complete remission. Of note, 14.3% in the budesonide group and 28.6% in the placebo group did maintain partial histologic remission (5–20eos/HPF). In the second study,19 children in complete remission (<1eos/HPF in both distal and proximal esophagus) with high-dose fluticasone (1760μg/day) underwent a 50% dose reduction and were re-evaluated 3 months later. 73% of responders were kept under complete histologic remission with half-dose fluticasone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare to have no conflicts of interest.