Although research in the area of sustainable supply management (SSM) has evolved over the past few decades, knowledge about the processes of emergence and innovation of SSM practices within organizations is surprisingly limited. These innovation processes are, however, important because of the considerable impact they may have on resulting sustainable practices and because of SSM's complex societal and intra-firm challenges. In a process study on management innovation, the sequences of SSM innovation processes in two exemplar case companies are studied to address: ‘What are the sequences through which SSM emerges within exemplar organizations?’, and ‘In what way do management innovation processes influence resulting SSM practices?’.

We build on literature regarding firstly management innovation and secondly communities and internal networks of practice. An SSM innovation model and propositions are developed, proposing how the process of management innovation affects SSM practices and firm performance in a broader perspective.

The strategic significance of sustainable supply management (SSM), including related topics such as sustainable operations and sustainable logistics, is increasingly acknowledged within both academia and industry. SSM addresses sustainability in the inbound part of supply chain management. Many authors have realized that SSM1 is an entirely new way of working (Pagell and Shevchenko, 2014). Pagell and Wu (2009) for example studied what is characteristic of SSM processes in exemplars. They concluded that the exemplar companies had made a radical break with traditional SCM approaches.

For radically new SSM practices however, new business models are needed (Pagell and Shevchenko, 2014). This implies that progressive companies have gone through management innovation processes in order to get sustainable SCM practices. Management innovation refers to ‘the invention and implementation of a management practice, process, structure, or technique that is new to the state of the art and is intended to further organizational goals’. (cf. Birkinshaw et al., 2008).

Despite the growing body of SSM literature (Touboulic and Walker, 2015), scant attention has been paid to the management innovation process which entails the emergence and development of sustainable practices in the supply chain. For several reasons however, it is of substantive interest for the SSM field of research to study processes of how SSM emerges and develops as a management innovation. First of all, SSM management innovation processes are in all likelihood steering resulting practices and their effectiveness, which makes them interesting and important factors in themselves (cf. Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009). Secondly, insights into exemplar SSM innovation processes will help practitioners and policy makers (Walker et al., 2012) to make informed decisions about innovation processes. The SSM processes are relatively new, tacit in nature and complex (Gold et al., 2010), and so their development poses a novel challenge to adopting companies. Finally, from the perspective of management innovation, SSM is interesting as well since it is highly complex in several respects: it requires the expertise of different functional areas, it involves numerous internal and external stakeholders relationships (Gold et al., 2010), and it has ethical and societal dimensions which touch public interest.

Through process studies in two exemplar companies, this research focusses on gaining insights into the innovation process of SSM, its emergence and its establishment within the boundaries of an organization, and into the influence of this process on resulting SSM practices. In line with the rational perspective on Management Innovation (cf. Birkinshaw et al., 2008), we focus on (1) its development sequences at the micro-organizational level of (2) actors and firm communities, and within those sequences (3) the role of knowledge accumulation. This informs us about the innovation process that was pursued and the rationale behind it.

The research questions are:

- 1.

What are the sequences through which SSM emerges within exemplar organizations?

- 2.

In what way do management innovation processes influence resulting SSM practices?

Our process studies in two exemplar case companies elucidate the emergence and internal diffusion of SSM, its sequences and its impact. In this process study we connect two areas of research (SSM and Management Innovation literature).

For SSM literature, we provide insights in an under-researched area of innovation processes itself and its influence on resulting practices. In the specific context of SSM, a sequences model outlines the emergence of Communities of Practice (CoPs) which transform to an internal Network of Practice (iNoP) and the distinctive roles of key actors like pioneers and leaders throughout those sequences and the need for tacit knowledge which is required about internal cross-functional collaboration on the one hand and external inter-firm collaboration. Besides, the influence of management innovation processes on SSM practices is elucidated. Next, in the area of management innovation literature, this work adds the specific insights of a SSM process study, meeting calls for studies looking into the process of creation and implementation of management innovation (Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009).

Theoretical backgroundSustainable supply managementSSM adds a dimension of sustainability to the field of supply management. It can be defined as the management of material, information and capital flows, as well as cooperation among companies along the inbound supply chain, while taking economic, environmental and social dimensions into account (cf. Seuring and Müller, 2008). SSM is vital for companies that strive to be sustainable, since for many companies over half of their turnover comes from services or products bought from suppliers. This implies that a firm's inbound supply chain offers substantial potential for influencing its triple-bottom-line (Handfield et al., 2005; Paulraj, 2011).

Research on sustainability in the supply chain has evolved over the past two decades, as has been acknowledged by various literature reviews (e.g. Carter and Easton, 2011; Sarkis et al., 2011). This has resulted in a broad array of studies, ranging from its profitability (Golicic and Smith, 2013) and the capabilities and antecedents required (Bowen et al., 2001; Gattiker and Carter, 2010; Pagell and Wu, 2009; Paulraj, 2011; Reuter et al., 2010) to organizations’ motivation and barriers to strive for sustainable supply chains (Hofer et al., 2012; Walker et al., 2008). Considerable attention has been paid in the past to the business case for sustainable business in general (Margolis and Walsh, 2003; Orlitzky et al., 2003) and for SSCM and SSM in particular (Golicic and Smith, 2013). However, because of the widely acknowledged, compelling need for sustainability, the challenge has changed from “whether” to act in a sustainable way to “how” to act in a sustainable way (Kleindorfer et al., 2005; Pagell and Wu, 2009). Economic gains alone are too narrow as a motivation for SSM (Pagell and Shevchenko, 2014).

Several studies have acknowledged that progressive SSM practices involve radical changes compared with traditional supply management practices (Pagell and Shevchenko, 2014) in terms of, for example, non-economic performance criteria and supply base management (Pagell and Wu, 2009). These studies have produced interesting findings on the characteristics of radically innovated SSM practices. These radically new practices imply that exemplar companies have gone through processes of management innovation, which have resulted in these new organizational practices and processes. These management innovation processes are of real interest in their own right, since the process of SSM emergence and innovation can affect resulting SSM practices and sustainable outcomes (cf. Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009). In addition, SSM processes are relatively new and complex (Gold et al., 2010) and pose a challenge of inter-firm collaboration to adopting companies. This is a challenge in which far more performance criteria have to be met than for traditional core operational issues (Gold et al., 2010).

However, despite the growing body on SSM literature (see Touboulic and Walker, 2015 for a recent literature review), management innovation processes related to the emergence and implementation of SSM, have hardly received attention. Illustrative for this void in research is that, based on literature research on socially and environmentally responsible procurement, Hoejmose and Adrien-Kirby (2012) included a full section on implementation, which outlined implementation of and issues to do with codes of conduct, rather than anything to do with implementation of innovative SSM. Based on their structured literature review on theories in sustainable supply chain management, Touboulic and Walker (2015) also conclude that the evolution of business practices has not been thoroughly explored. Hence, they propose that future research focuses on the SSM implementation process by framing it as a change in organizational practices (Touboulic and Walker, 2015, p. 35). This plea is in line with an observation of Pagell and Wu (2009) that so far only fragmented information regarding the process toward SSM was available. No coherent insights have emerged regarding the innovation processes organizations deploy to internally develop and prepare SSM processes and regarding challenges in these innovation processes. In this respect, the SSM domain can benefit from the emerging knowledge base regarding management innovation.

Management innovationThere is a large, multi-disciplinary and diverse body of academic literature on innovation (e.g. Anderson and Tushman, 1990; Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Fagerberg, 2004; Nelson and Winter, 1982; Tushman and Anderson, 1986; Van de Ven et al., 1999). Innovations can focus on different dimensions and so have different outcomes such as new products or services (product innovation), but also new production processes (process innovation) (Crossan and Apaydin, 2010) and new ways of organizing work (organizational innovation) (Fagerberg, 2004).

We study the processes of organizational innovation and more specifically of management innovation (Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Birkinshaw and Mol, 2006; Hamel, 2006; Lam, 2004), given the importance of SSM development as an innovation process. Management innovation is a relatively new and still under-researched form of organizational innovation (Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Birkinshaw and Mol, 2006; Damanpour et al., 2009; Vaccaro et al., 2010). Yet, it is a significant topic in the field of strategic management (Wu, 2010). In terms of management innovation, SSM can be defined as “a new set of practices and processes aimed at embedding sustainability in supply management” (cf. Birkinshaw et al., 2008). Birkinshaw et al. (2008) categorize four perspectives on management innovation. Firstly, the institutional perspective addresses institutional conditions which stimulate emergence and diffusion of management innovation; secondly, the fashion perspective views management innovation as a management idea that can be propagated on the market; thirdly, the cultural perspective incorporates organizational culture as an important condition for how management innovation is shaped in an organization; and, fourthly, the rational perspective has a central role for human agency.

Our perspective of management innovation in this research is related to the rational perspective, in line with our focus on processes of SSM innovation and the important role of decision-making by internal and external stakeholders (Gattiker and Carter, 2010; Sarkis et al., 2011; Wu and Pagell, 2011) and in line with the notion that human agency should get attention in management innovation (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). The rational perspective posits that management innovations are introduced by individuals with the goal of making their organization work more effectively. The rational perspective studies the roles of internal and external actors in the sequences in which management innovation develops within an organization at an operational level (Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Vaccaro et al., 2010). In line with the rational perspective, we study the roles of the actors involved in the SSM management innovation process.

Apart from the role of human agency, management innovation involves sequences. Birkinshaw and Mol (2006) and Birkinshaw et al. (2008) have pointed to somewhat common stages within the management innovation process. Birkinshaw et al. (2008) have developed theoretical stages of motivation, invention, implementation and labeling (which may occur iteratively), and they relate this to actions carried out by internal and external change agents. They have called for future research to study and make sense of management innovation sequences in practice. Other studies have also pointed to the sequences in time across different forms of innovation (Damanpour et al., 2009; Lam, 2004).

Communities and internal networks of practiceThroughout those ‘management innovation sequences’, it is particularly interesting to look at the role of actors and communities in this process. This is in line with our focus on the rational perspective on management innovation (Birkinshaw et al., 2008), in which human agency has a crucial role. As explained in the previous section, the human agency notion entails the involvement of internal and external actors who introduce innovative management practices to improve organizational effectiveness.

This fits nicely with the concept of Communities of Practice (CoPs), as identified in multinational enterprises (cf. Brown and Duguid, 1991; Roberts, 2006; Tallman and Chacar, 2011), being small, focused, localized groups of individuals within the company who have a mutual engagement in specific practices (Tallman and Chacar, 2011). In essence, a CoP is seen as a mechanism through which knowledge is held, transferred and created (Roberts, 2006, p. 641). Brown and Duguid (1991) argue that through an ongoing process of adapting to changing membership and changing circumstances, such communities can be hotspots for innovations. Building on this argument, Cox (2005, p. 529) proposes that organizations should value and foster CoPs as informal networks which actually figure out how to implement forms of shop floor innovation. Individuals involved in such communities typically share (largely tacit) knowledge and understanding, language, culture, and values on a specific joint practice (Tallman and Chacar, 2011).

Despite their innovation potential, it should be realized that CoPs are not static, yet emerging informal entities, that can technically speaking not be established by senior management. Still, management can facilitate and actively support emerging CoPs (Roberts, 2006). Such managerial efforts may in turn foster the development of Internal Networks of Practice, INoPs. Tallman and Chacar (2011) describe such INoPs as informal networks that combine multiple CoPs around a joint practice and that support the development of common knowledge and routines, building on a shared architecture. This description already implies that, unlike CoPs, INoPs are less likely to arise naturally, yet their development requires a ‘delicate intervention’ (Tallman and Chacar, 2011, p. 280) by a firm's senior management. The strategic rationale for such interventions is that the firm-level architecture created via INoPs can be seen as valuable and rare, thus providing opportunities to create novel knowledge as a source of competitive advantage.

Since knowledge is indeed commonly seen as key to all forms of innovation (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995), it is particularly interesting to look at the accumulation of knowledge (Wu, 2010) in CoPs and INoPs. Organizational knowledge comprises tacit knowledge of individuals, which should be integrated into the explicit knowledge base of the firm (Lam, 2004). In other words, organizations should capture and utilize the accumulated knowledge of its actors in order to reap the potential strategic benefits from management innovations (Wu, 2010).

So, in conclusion, while studying management innovation processes in the area of SSM, particular attention should be paid to firstly the role of human agency (as well in communities and networks of practice), secondly the sequences within this innovation process and finally the process of knowledge accumulation in the area of SSM.

Research methodsCase based process studiesMuch more time needs to be spent on “studying the presently small number of supply chains that are trying new things that do not fit expected patterns and so on.” (Pagell and Shevchenko, 2014). Two qualitative case studies form the empirical part of this process research in which we aim to investigate how exemplar organizations do indeed try to implement such ‘new things’. Qualitative case studies “primarily use contextually rich data from bounded real-world settings to investigate a focused phenomenon” (Barratt et al., 2011), and they are suited to process studies that aim to understand patterns of evolution over time (Langley and Abdallah, 2011), such as processes of management innovation. Collaboration with the case companies encourages the exploration of research territory that is relevant to the industry (Guide and Van Wassenhove, 2007).

The unit of analysis is the innovation process of SSM practices within two selected multinational enterprises (MNEs) at the micro-organizational level of their actors and firm communities. Our case data are used as process narratives in order to study change and narrate sequences of events or ‘change stages’ within ‘real entities’ (Van de Ven and Poole, 2005). Narratives can provide rich data on real phenomena (Doz, 2011) when aiming to develop process theories based on deeper structures, that are not directly observable in practical settings (see also Welch et al., 2011). In our cases, the sequence of events in their SSM development and the roles of various actors in this development process are ‘narrated’.

Sampling and data collection methodsSampling of more than one case enables cross-case comparison and adds confidence in findings (Miles and Huberman, 1994). We selected a limited number of cases (two), as is often encountered in process research (Van de Ven and Poole, 2005). Barratt et al. (2011) and Siggelkow (2007) point out there is room for one or two cases when the research study uses exemplars. In our research, both companies decided to go public with their “company-wide” sustainability announcement, which allowed us to witness the actual transition process toward full-company SSM practices.

When selecting the two cases, purposive sampling, based on theoretical underpinnings, was used (Eisenhardt, 1989; Miles and Huberman, 1994). Our research focus is on SSM which has been subject to substantive management innovation. This implied the selection of exemplar companies, which were ahead of others in terms of their SSM. Two exemplar companies in the field of SSM were selected, based on publicly available documentation and a range of third party ratings, reports and rankings. For the last five years at least, both companies had been consistently rated among the highest scorers in their industry by the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, DJSI (Fowler and Hope, 2007). They had also been highly ranked by other indicators such as, amongst others, the ‘Responsible Supply Chain Benchmark’ and (one of the two case companies) in ‘the Global 100 List’.2 Secondly, in both case companies supply management is of strategic importance to their core supply chain processes.

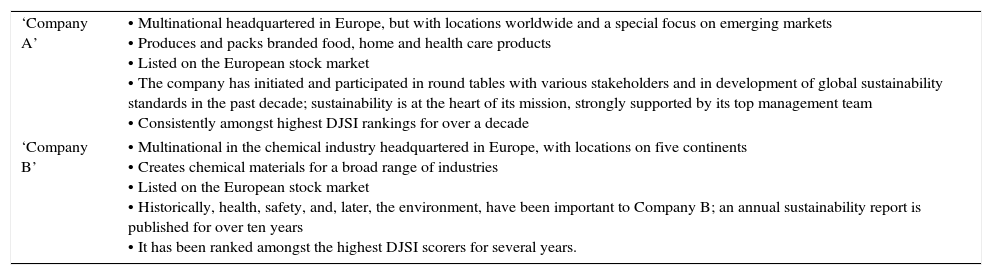

Both case companies are multibillion Euro companies with tens of thousands of employees. Table 1 introduces shortly both case companies.

Introduction to the case companies.

| ‘Company A’ | • Multinational headquartered in Europe, but with locations worldwide and a special focus on emerging markets • Produces and packs branded food, home and health care products • Listed on the European stock market • The company has initiated and participated in round tables with various stakeholders and in development of global sustainability standards in the past decade; sustainability is at the heart of its mission, strongly supported by its top management team • Consistently amongst highest DJSI rankings for over a decade |

| ‘Company B’ | • Multinational in the chemical industry headquartered in Europe, with locations on five continents • Creates chemical materials for a broad range of industries • Listed on the European stock market • Historically, health, safety, and, later, the environment, have been important to Company B; an annual sustainability report is published for over ten years • It has been ranked amongst the highest DJSI scorers for several years. |

Various data collection methods are used in order to enable triangulation. Major sources of information were: (i) semi-structured interviews, (ii) archival data from internal and external publications, including annual reports, sustainability reports, company publications, and newspaper articles about the company. In addition, (iii) an international supply chain conference in Europe (2010) at which both case companies presented the outlines of their SSM approaches, was attended.

An interview guide was developed for the semi-structured interviews, and verified during two separate peer reviews with supply management experts, as part of the case study protocol which was developed before data collection to enhance reliability of the case studies (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2009). In addition, also serving the purpose of verifying the interview guide, a small pilot study in another exemplar multinational from the electronics industry was conducted upfront. This pilot study did not result in major changes in the setup; it did allow minor improvements to the protocol. Interviews followed, but were not restricted to the interview guide (see Appendix A). For both case studies, interviews happened to take place just before the company-wide launch of sustainability targets involving SSM. The researchers only knew that these launches were planned after the research had started, since this information was highly classified and not publicly available. Due to the timing of the case studies, important parts of the management innovation process were still in an early stage and recently planned. This meant that only a select number of people were aware and involved in the innovations and could be interviewed. Those interviewees from each case company happened to have different functional backgrounds. Interviewees from different functional areas, provide multiple approaches to the same phenomena and the possibility of triangulation, which enhances the reduction of social desirability biases (Podsakoff et al., 2003). For Company A, this meant interviewing a select group of the Global Sustainable Procurement Director, the Procurement Director Commodities Europe, the Supply Management Director of Supplier Assurance and Compliance and the Global Supply Chain Director Sustainable Agriculture. For Company B the Vice President Purchasing Chemicals, the Sustainability Director and the Vice President of R&D of one of its major business units were interviewed. All interviews were recorded. Interviews varied from one to three and a half hours and took place mainly by visiting sites in Europe.

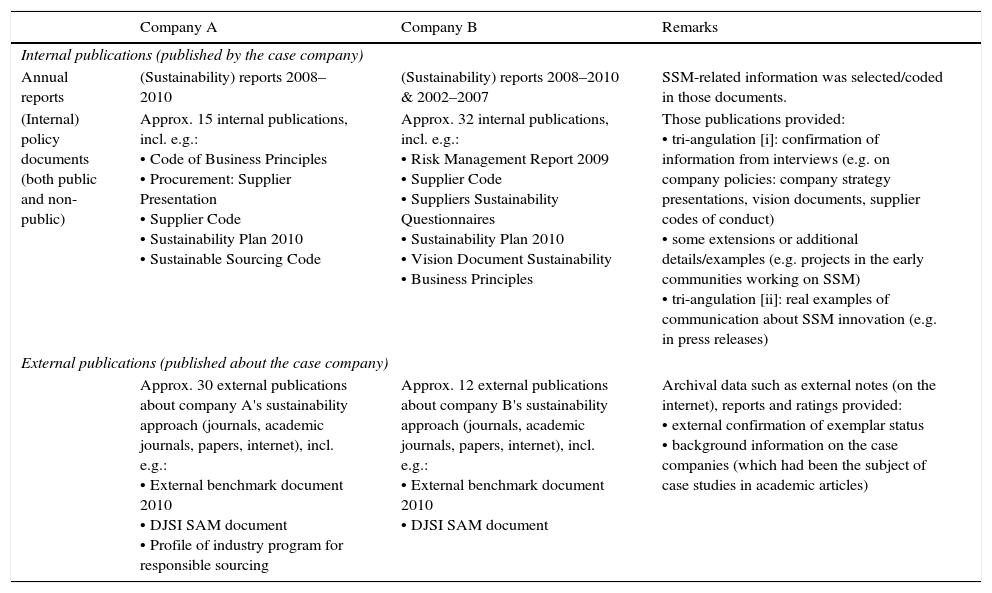

Archival data from internal and external publications were a second important data source (see Table 2 for an overview). The archival data helped to validate and in some cases extend information from interviewees.

Archival data from internal and external publications.

| Company A | Company B | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal publications (published by the case company) | |||

| Annual reports | (Sustainability) reports 2008–2010 | (Sustainability) reports 2008–2010 & 2002–2007 | SSM-related information was selected/coded in those documents. |

| (Internal) policy documents (both public and non-public) | Approx. 15 internal publications, incl. e.g.: • Code of Business Principles • Procurement: Supplier Presentation • Supplier Code • Sustainability Plan 2010 • Sustainable Sourcing Code | Approx. 32 internal publications, incl. e.g.: • Risk Management Report 2009 • Supplier Code • Suppliers Sustainability Questionnaires • Sustainability Plan 2010 • Vision Document Sustainability • Business Principles | Those publications provided: • tri-angulation [i]: confirmation of information from interviews (e.g. on company policies: company strategy presentations, vision documents, supplier codes of conduct) • some extensions or additional details/examples (e.g. projects in the early communities working on SSM) • tri-angulation [ii]: real examples of communication about SSM innovation (e.g. in press releases) |

| External publications (published about the case company) | |||

| Approx. 30 external publications about company A's sustainability approach (journals, academic journals, papers, internet), incl. e.g.: • External benchmark document 2010 • DJSI SAM document • Profile of industry program for responsible sourcing | Approx. 12 external publications about company B's sustainability approach (journals, academic journals, papers, internet), incl. e.g.: • External benchmark document 2010 • DJSI SAM document | Archival data such as external notes (on the internet), reports and ratings provided: • external confirmation of exemplar status • background information on the case companies (which had been the subject of case studies in academic articles) | |

A third source of information, in addition to interviews and archival data, was an international supply chain conference (2010) at which both case companies presented their SSM strategy. Notes and recordings made at this conference served especially to broaden and strengthen researchers’ insights into the companies’ strategies and communication about their SSM processes.

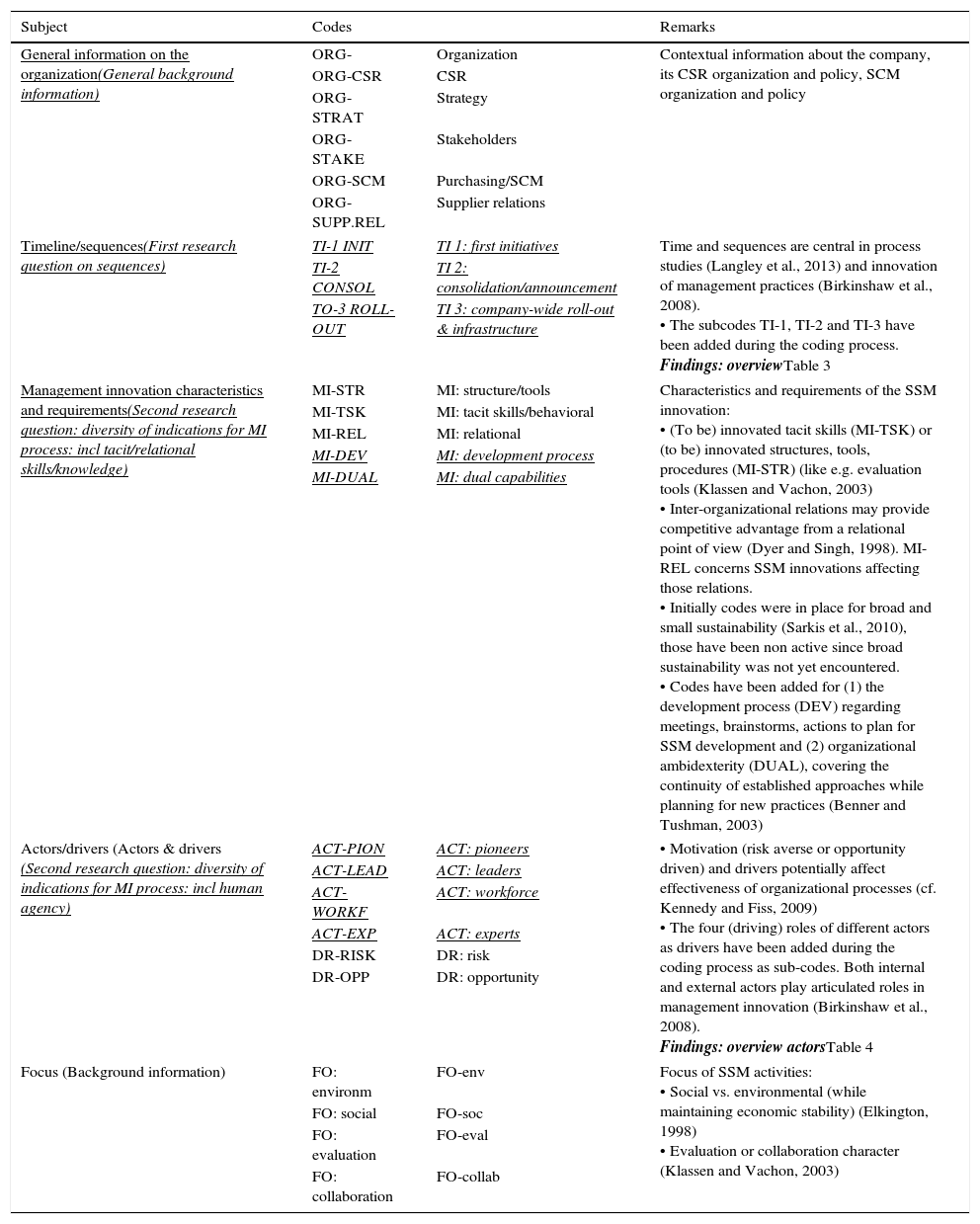

Data analysis methodsIn the first phase of our data analysis, a preliminary coding list had been set up ex ante, with general categories based on the research questions (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Transcripts were read various times in order to identify and apply appropriate codes and sharpen, adapt and detail the coding list (see Appendix B). For example, actor roles could be added according to the roles we encountered in our research. Transcripts and archival data were reread and recoded. Final analysis of coding was carried out independently by two different researchers to increase reliability (Barratt et al., 2011; Eisenhardt, 1989). Differences in interpretations of data and codes were discussed and resolved until full consensus was reached between the two researchers.

In the second stage of data analysis, emerging patterns and themes were identified per case, resulting in diagrams and time lines of events. This within-case analysis aimed to provide an in-depth understanding of how SSM management innovation had evolved in the two case companies. Diagrams served to connect and select major themes iteratively.

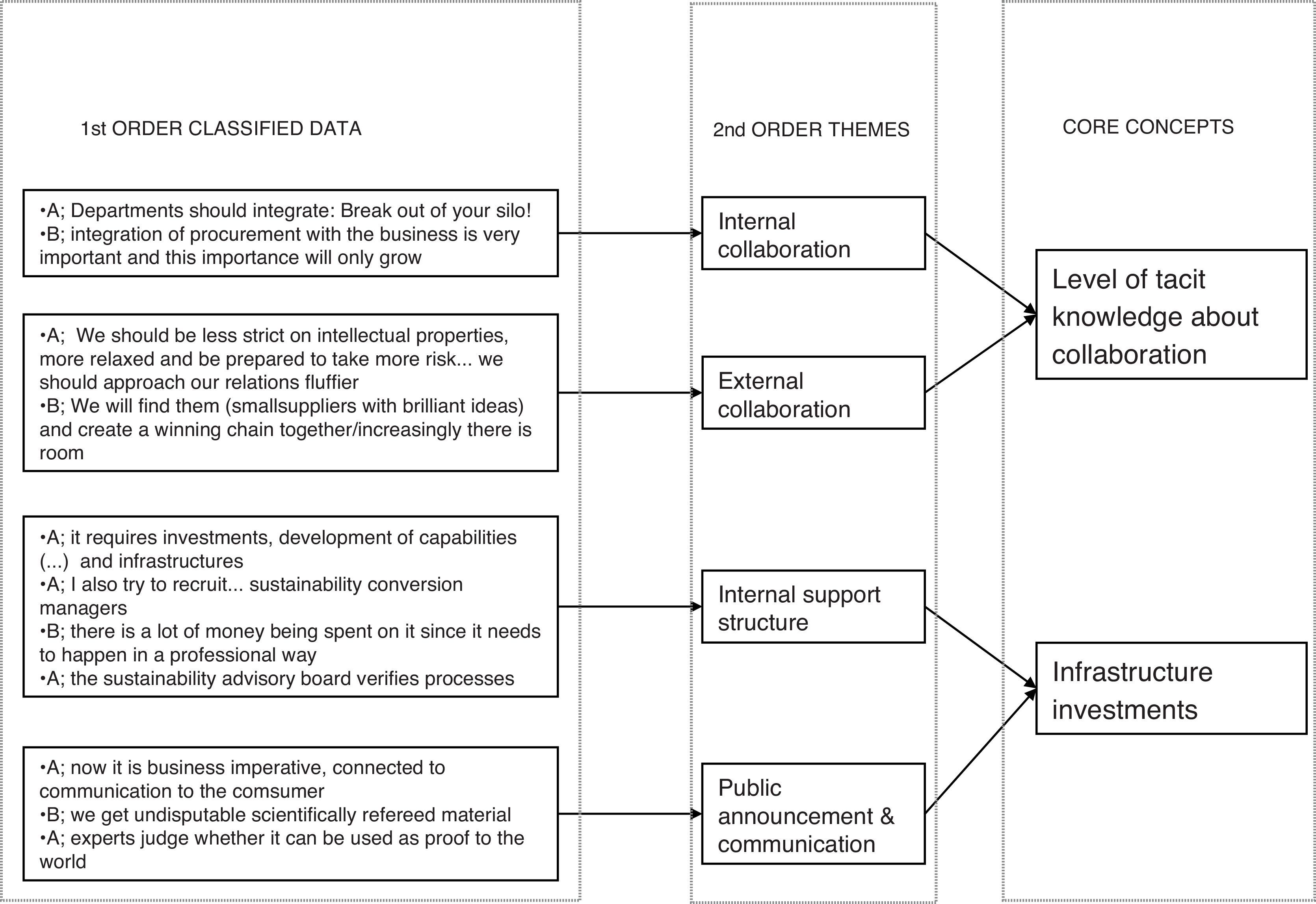

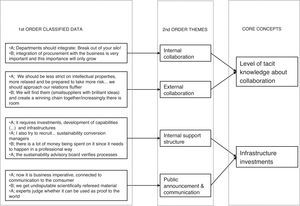

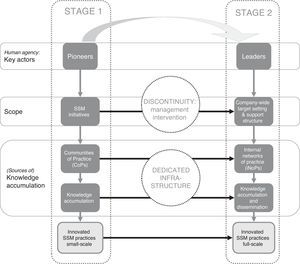

In the third stage of our data analysis, displays (Miles and Huberman, 1994) were used to capture cross-case similarities and contrasting patterns. Sequences were analyzed to find out how SSM was innovated, including the position of knowledge and the role of actors in those sequences. An illustration of the connection between the data and higher-level constructs is provided in Fig. 1. From our case data we found preconditions that facilitated the transition between major stages of management innovation, i.e. from the early work of pioneers in small communities to company-wide adoption of SSM practices. Fig. 1 illustrates how those preconditions appeared by clustering raw data into themes.

Finally, representatives of both case companies validated the analysis to enhance the credibility of the findings. This did not lead to major changes in the contents of the case descriptions.

Case findingsWe first present a within-case description of the SSM process in our two case companies. Subsequently, a cross-case comparison is made to capture both similar patterns and differences.

Within-case process description Company AIn the mid-nineties, the environmental officer of Company A put to a board member the sustainability of sourced materials as “something relevant that will increasingly need attention”. The board member recognized and shared this opinion and the employee was given a budget to develop his ideas. Sustainable agriculture was selected as relevant to the company and the initiative has gradually grown since then. In 1998 it became a separate program, of which the first five years were spent on developing sustainability standards for five key materials. In addition, elsewhere in the organization, other projects were set up, such as, for instance, a sustainable dairy program that has resulted in the use of sustainable milk for selected products. Preliminary participation in industry initiatives was also established.

As an independent and separate step, in 2006, a small team was formed for what was called “responsible sourcing”. Company A distinguishes responsible sourcing and sustainable sourcing very explicitly as different approaches. Responsible sourcing means to mitigate risks by ensuring full supplier compliance with the business code and absolute mandates (like: no child labor, forced labor, corruption or environmental violations). A process of audits and self-verification has been set up to support responsible sourcing. In contrast, sustainable sourcing represents a pro-active approach to realize more ambitious sustainability targets in collaboration with selected suppliers. As phrased by the Global Sustainable Procurement Director: “Sustainable sourcing is a layer which comes on top of responsible sourcing. Responsible sourcing are the obligations about which we do not need to talk a lot…” For responsible sourcing, Company A connected to an on-line data exchange between suppliers and customers in 2009, enabling supplier assessments to be shared via a common database.

In 2010, top management presented a company-wide “Sustainability Plan” to the world. This plan has ambitious revenues growth targets for the decade until 2020, while simultaneously aiming to reduce environmental and social impact throughout the supply chain. The Sustainability Plan focuses on the whole life cycle of the products in which the sourcing of raw materials is recognized as an important impact area for sustainability. Greenhouse gases, use of water, waste management and sustainable agricultural sourcing are presented as pillars of the environmental targets.

In order to realize the commitments announced, Company A has established an internal team to support the company-wide sustainability approach both internally and externally. This team is expected to tackle SSM's complex challenges, which are outlined by the Global Sustainable Procurement Director as “…new business models of working with suppliers that require investments, development of capabilities, training people, courses and infrastructures.” This global “Sustainable Procurement Team” of five people provides internal training on sustainable procurement for internal employees and addresses communication and co-operation with suppliers. Moreover, this team trains selected suppliers in sustainable practices. A second team works on “sustainable sourcing development”, being responsible for the further optimization of standards and policies and a new strategy for non-renewable materials. This team aims to tackle more strategic questions about appropriate approaches toward sustainability and SSM.

The introduction of a company-wide SSM approach requires real change in the internal organization, as underlined by the Global Sustainable Procurement Director: “Departments should integrate: Break out of your silo! For this a mindset switch is needed…” In a similar vein, talking about external collaboration, he indicates that intellectual properties should not be managed too strictly: “We should be more relaxed and be prepared to take more risk; then suppliers open up, they can show their ideas…. We should approach our relations fluffier – our CEO emphasized this – and take calculated risks because then people will come to you. This is a mindset switch however.” This open attitude is stressed as the most vital change needed in the organization for successful company-wide SSM practices.

Within-case process description Company BCompany B's efforts to enhance sustainability throughout the supply chain started with scattered initiatives in some business units (BU's). Those initiatives varied considerably according to the different environments and challenges of those BU's and were not connected.

On a company level, a start was made from 2005 on to evaluate suppliers systematically in terms of minimum sustainability standards. Company B labels this as an early stage of SSM, initiated by its procurement department. The evaluation system is based on internal standards (like a code of conduct), procedures and audits. Audits are carried out by internal staff rather than external offices in order to learn from those audits and to coach and assist suppliers. In 2010, Company B publicly announced a company-wide strategy involving explicit target setting, which would affect sustainability in the Supply Chain for the next five years. With this strategy, sustainability is positioned as a value driver, rather than a compliance issue. Sustainability is one of the pillars that should support company B's maximum sustainable and profitable growth. The sustainability ambitions, reflected in the five-year targets, implied that over 75% of newly developed products should have a low ecological impact compared with the main competing solutions (based upon internal expert opinions), while half of the existing products should have a low ecological impact compared with the main competing solutions. Substantial increases in energy efficiency and reductions in greenhouse gases are also targets for the next ten years. Achieving these targets requires intense involvement of supply chain members. Since Company B controls only a small part of the life cycle, collaboration with supply chain members is important to reduce the overall ‘ecological footprint’.

Company B has started to work through a network structure with champions to integrate sustainability throughout the business. One sustainability champion per department is selected and assigned, based on his/her affinity with sustainable business. These champions are selected to be linking pins between the sustainability activities and policies from staff departments like the central sustainability department and their own department or business unit. They are given a role rather than a function. Alongside this network structure, the Purchasing Strategic Dialogue Team, in which purchasing managers of the BUs participate, develops ideas about how to develop sustainable sourcing. The aim is to include customized and far-reaching collaboration with suppliers. In parallel with the network structure and the strategic dialog team, external experts are involved, amongst others to share knowledge, but also as a means of external verification.

The introduction of a company-wide SSM approach will require substantial change in the attitude toward internal and external collaboration. The Sustainability Director indicates how the procurement function should be further integrated in the business: “Integration of procurement with the businesses is very important, and this importance will only grow. If we can sell “green”, then we have to pay more attention to that in terms of procurement ….“ He continues in a similar vein about suppliers: “We need to change from ‘liability thinking’ to ‘asset thinking’.”… The need for a more open attitude toward potential new suppliers, is also stressed by the Vice President Purchasing Chemicals, “Some suppliers will disappear, but we will win others, like the little boutiques that have brilliant ideas which not yet have been recognized amidst the big ones. We will find them and create a winning chain together ….” In company B, internal and external collaboration have been identified as absolute key enablers for successful company-wide SSM.

Cross-case comparisonSequences of management innovationWhen comparing the timelines and the sequences of development related to SSM for both cases, it turns out that both cases show a pattern of disruption in the process of innovating SSM through management intervention, with the aim of strengthening SSM in the organization.

First, there is a period of small-scale SSM initiatives over many years. Those first initiatives can be described as projects that try out and set out new directions for SSM, undertaken on a relatively small scale by small groups.

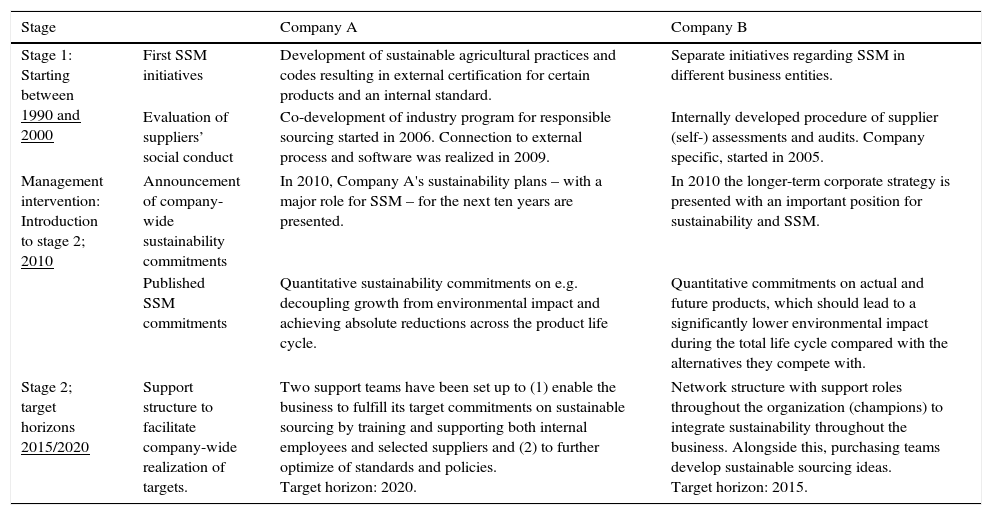

Second, in 2010 both companies mark the start of a new period by the public announcement of ambitious company-wide targets, instigated by the respective management teams. The policies announced cover the life cycle of the products and so heavily involve supply management in both cases. Moreover, both announcements include quantitative corporate targets for the coming ten years. Both companies also developed new processes and responsibilities to facilitate a company-wide roll-out. Based on the timelines in both companies, we can identify two subsequent, main stages of SSM development (see Table 3).

Cross-case comparison for emergence of SSM.

| Stage | Company A | Company B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Starting between 1990 and 2000 | First SSM initiatives | Development of sustainable agricultural practices and codes resulting in external certification for certain products and an internal standard. | Separate initiatives regarding SSM in different business entities. |

| Evaluation of suppliers’ social conduct | Co-development of industry program for responsible sourcing started in 2006. Connection to external process and software was realized in 2009. | Internally developed procedure of supplier (self-) assessments and audits. Company specific, started in 2005. | |

| Management intervention: Introduction to stage 2; 2010 | Announcement of company-wide sustainability commitments | In 2010, Company A's sustainability plans – with a major role for SSM – for the next ten years are presented. | In 2010 the longer-term corporate strategy is presented with an important position for sustainability and SSM. |

| Published SSM commitments | Quantitative sustainability commitments on e.g. decoupling growth from environmental impact and achieving absolute reductions across the product life cycle. | Quantitative commitments on actual and future products, which should lead to a significantly lower environmental impact during the total life cycle compared with the alternatives they compete with. | |

| Stage 2; target horizons 2015/2020 | Support structure to facilitate company-wide realization of targets. | Two support teams have been set up to (1) enable the business to fulfill its target commitments on sustainable sourcing by training and supporting both internal employees and selected suppliers and (2) to further optimize of standards and policies. Target horizon: 2020. | Network structure with support roles throughout the organization (champions) to integrate sustainability throughout the business. Alongside this, purchasing teams develop sustainable sourcing ideas. Target horizon: 2015. |

Throughout the two stages shown in Table 3, differences between both case companies also become visible. The scattered initiatives in the first stage seem to be more diverse in company B where separate initiatives regarding SSM emerge in different business units. Initiatives in company A are diverse as well, but in general they share a focus on the development of sustainable (industry) practices and codes. A second noteworthy difference is found in the evaluation of suppliers’ social conduct. Company B considers its “evaluation” activities as an important first initiative in the process of SSM, designed to mitigate risks. Company A, by contrast, labels evaluation activities as “responsible sourcing”, supported by a separate department of supplier assurance and compliance, and not as part of SSM. Both companies introduced a system of evaluation around 2005. However, whereas company B introduced a company-specific procedure of supplier (self-) assessments and audits carried out by its own employees, company A participated in the development of an industry program for responsible sourcing.

In addition to the cross-case differences in stage one, a major difference in the second stage concerns the support structure that both companies have set up for company-wide consolidation of SSM. Company B's network structure has champions whose aim is to integrate sustainability throughout the business. Champions are selected on the basis of their affinity with sustainability and are assigned a role rather than a function. At a central level, the sustainability coordination group and the purchasing strategic dialog team can both provide support. Company A has two central, dedicated support teams for sustainable sourcing, which build on the experiences of the first stage. One team enables the business to fulfill its target commitments, while another team is responsible for the further optimization of standards and policies.

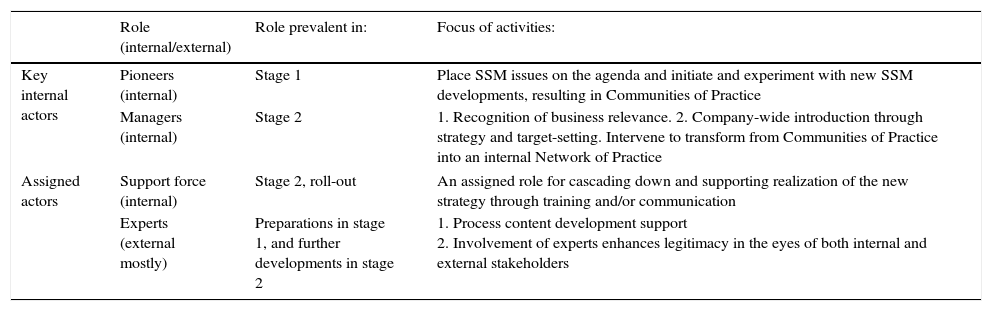

Key actors and assigned actorsDifferent types of actors play a role in during the sequences of SSM management innovation in our cases: early pioneers, top management and assigned actors like external experts and the internal support force. In both case companies, early pioneers start SSM initiatives and subsequently top management becomes an important driving force, placing it high on the corporate agenda by setting targets for the entire company and publicly announcing these targets. An overview of four archetypal actor roles that have been identified is provided in Table 4.

Archetypal internal and external actor roles throughout the two main stages.

| Role (internal/external) | Role prevalent in: | Focus of activities: | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key internal actors | Pioneers (internal) | Stage 1 | Place SSM issues on the agenda and initiate and experiment with new SSM developments, resulting in Communities of Practice |

| Managers (internal) | Stage 2 | 1. Recognition of business relevance. 2. Company-wide introduction through strategy and target-setting. Intervene to transform from Communities of Practice into an internal Network of Practice | |

| Assigned actors | Support force (internal) | Stage 2, roll-out | An assigned role for cascading down and supporting realization of the new strategy through training and/or communication |

| Experts (external mostly) | Preparations in stage 1, and further developments in stage 2 | 1. Process content development support 2. Involvement of experts enhances legitimacy in the eyes of both internal and external stakeholders | |

Both cases demonstrate that “knowing how to collaborate” is urgently needed to enhance SSM, for both internal and external relations. In terms of internal relations, employees working on SSM need to understand that, despite resistance, intra-organizational commitment and cross-functional collaboration are core conditions for successful implementation of SSM (Gattiker and Carter, 2010). In terms of external relations, like suppliers, collaboration involves the sharing of ideas and planning in an atmosphere of openness between firms (Gold et al., 2010; Seuring and Müller, 2008).

The first management innovation stage concentrates on knowledge development in a set of small scale initiatives. The second management innovation stage also concentrates on knowledge dissemination through facilitating support structures, alongside knowledge development on a wider scale. Specifically tacit knowledge about collaboration inside and outside the organization is stressed as a requirement and as the key to successful company-wide implementation of SSM.

Theoretical elaboration and propositionsCommon patterns to do with sequences, actors and knowledge accumulation and dispersion can be drawn from both cases. We elaborate on those patterns in this section, resulting in an overview of (1) SSM innovation sequences, actors and knowledge accumulation and (2) influences of innovation processes on resulting SSM practices.

Sequences, actor roles and knowledgeCoPs, INoPs and actorsThe small communities, which were already working on SSM before any company-wide initiatives took place, resemble the CoPs described earlier in this paper. In both case companies, the process of emerging SSM initiatives share a bottom-up mechanism that expands to a CoP. This first stage of CoP development, which extends over many years, confirms that management innovation is a diffuse and gradual process (Birkinshaw and Mol, 2006), providing important experiences and knowledge as a basis for further company-wide management innovation within SSM. Key identified actors in these early stages of emerging SSM initiatives are ‘pioneers’ and ‘leaders’. We describe pioneers as individuals (typically at the middle or lower level of the organization) who set up SSM initiatives which take root somewhere in the organization. These pioneers resemble environmental project champions (Gattiker and Carter, 2010), who face the challenge of overcoming intra-organizational resistance, mainly across functional boundaries. In our cases, pioneers initiated new developments, while top management facilitated them, in line with the usual spontaneous emergence of CoPs, which benefit from managerial cultivation (Roberts, 2006). Although management innovation is not necessarily developed by top management, they may create the organizational conditions for experimentation with and introduction of new management processes, practices or structures (Vaccaro et al., 2010).

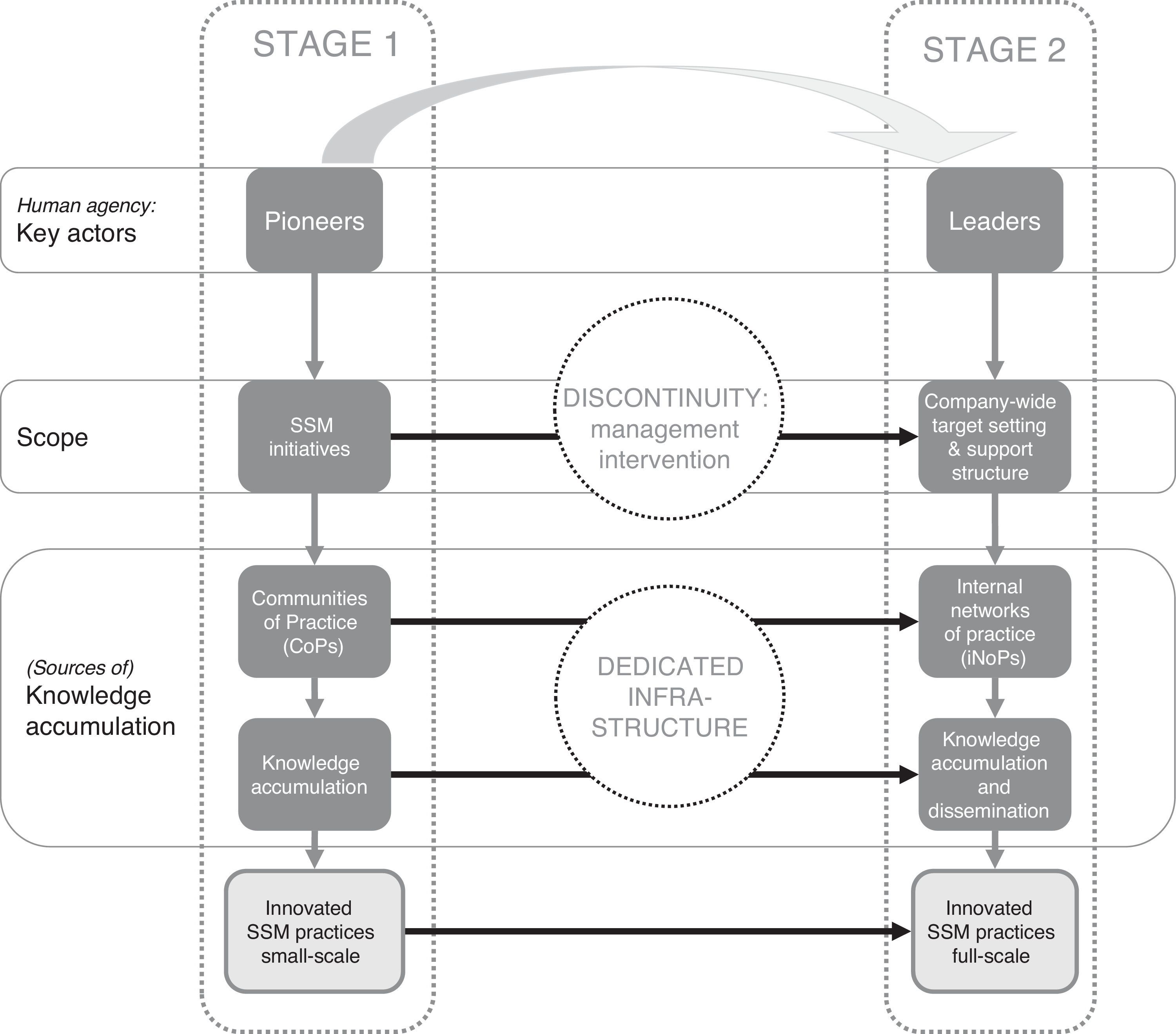

After a relatively long period of CoPs emergence, both case companies made a drastic change to INoPs, a company-wide approach comprising larger, more dispersed groups of communities and individuals. This change usually requires dedicated managerial intervention, which in our cases mainly took the form of (i) preparations and public announcement of company-wide targets, (ii) setting up of a dedicated infrastructure to cascade the new targets across all operations.

Target setting appeared to have two major effects. Its first effect derives from its public character. Public commitments are like pledges to society, which would not normally be made if they had no societal relevance. The public announcement of targets by both case companies can be seen as a distinct form of pro-active engagement with key stakeholders and as communication to customers, which is recognized as a major facilitator of SSM (Carter and Easton, 2011). Secondly, the public announcement of targets underlines the importance of SSM to the internal organization and provides internal momentum to employees.

Besides public target setting, a second managerial intervention in our cases is the setting up of a dedicated infrastructure to strengthen SSM as part of the company-wide sustainability approach. Typically, management innovations in general are intangible and emerge, like CoPs, without a customized infrastructure (Vaccaro et al., 2010). However, for their company-wide consolidation into an INoP (Birkinshaw et al., 2008), both companies developed a customized infrastructure, which included supporting roles, like the champion structure within Company B or the sustainable procurement team within Company A. We here define infrastructure as the set of measures, new roles and organizational changes that have been set up to facilitate the company-wide roll-out of SSM.

In terms of actors in the second phase, the role of leaders changes from an initially facilitating role with regard to CoPs to a driving role with regard to consolidation into an INoP. Due to its prominent role within the organization, top management is vital (Carter and Jennings, 2004; Pagell and Wu, 2009) and can influence management innovation considerably (Vaccaro et al., 2010).

Role of knowledgeIn the case organizations, the level of tacit knowledge about collaboration has been indicated as vital. Tacit knowledge or “know-how” is the ability to put explicit knowledge (“know-what”) into practice and is hard to spread or co-ordinate (Brown and Duguid, 1998). It is intuitive and unarticulated and of key importance in organizational learning and innovation (Lam, 2000). Collaboration is characterized by tacit knowledge integration, which occurs through information exchange in a rich communication setting (Klassen and Vachon, 2003).

The main challenge of knowledge management throughout the stages of innovation lies specifically in the transfer of tacit knowledge. The more tacit the knowledge, the less likely it is that it will be understood outside the CoP where it has been developed (Tallman and Chacar, 2011), making it harder to spread. In terms of collaboration, which is tacit in nature and has been indicated by interviewees as a key condition for enhancement of SSM and a key need within their organization, it underlines the importance of having a good level of “knowing how to collaborate” in place throughout the organization.

Enablers of ‘knowing how to collaborate’ refer to generic, organizational skills that are not needed solely for SSM. Yet, interviewees explicitly identified collaborative skills as a key area requiring their attention during the transition to an INoP, and one in which considerable improvements should be made. This implies that SSM innovation activities also require a focus on and the development of generic, collaborative skills in our case companies. This finding at first sight appears to be counterintuitive, since such collaborative skills might be expected to be in place in globally operating companies where inter- and intra-organizational collaboration is vital for so many processes.

‘Knowing how to collaborate’ applies first of all to cross-functional collaboration between departments having to do with SSM inside the organization. Secondly, it refers to external collaboration between organizations within the supply chain.

We therefore advance the following proposition for exemplars:Proposition 1 The emergence of SSM in communities of practice, succeeded by a discontinuity through management intervention with public commitments, sequentially extends SSM practices into an internal network of practice.

In summary, throughout the sequences leading from CoPs to an iNoP, SSM knowledge is created, accumulated and spread with pioneers and leaders playing a prominent role. The discontinuity observed in the process of SSM innovation is caused by management intervention with organizational leaders playing a key role.

Influence of the management innovation process on resulting SSM practicesPath dependency between CoPs and INoPsManagement innovation can deliver a sustained first-mover advantage because of its context-specific character which cannot (easily) be copied. Throughout its sequences, specific organizational capabilities can be developed and, in combination with resources, be reconfigured to respond to the requirements of a changing environment.

This process involves a ‘path dependency’, also encountered in studies of dynamic capabilities (Teece, 2007). Path dependency refers to the history of an organization (Schreyögg and Kliesch-Eberl, 2007), implying that a firm's current position and its future depend on past developments. Sequences in management innovation may reveal such paths. For instance, SSM capabilities and the resources that are developed in CoPs can influence the potential of an INoP. Knowledge accumulation in the early stages is the context-specific basis for subsequent sequences.

In both case companies, the period of first SSM initiatives in small communities (CoPs) is relatively long up to two decades (see Table 3), providing valuable time for SSM knowledge accumulation, which was evidenced in both case companies. The companies benefit from a situation in these communities of practice where sustainable practices and approaches are developed and improved without explicit time pressure. Both knowledge on (1) sustainable practices itself like development of sustainable agricultural practices and codes, and (2) knowledge on management practices (evaluation practices, self-assessments, audits) is developed in depth as outlined in Table 3. This knowledge development provides a solid basis for the subsequent iNoP in which the in depth knowledge and experiences are shared and applied on a larger scale. We argue that the more developed SSM is in the early stages of CoPs, the stronger the basis for future, company-wide implementation and development, and so the greater the likelihood of incorporating SSM practices in the succeeding INoP. We therefore advance the following proposition:Proposition 2 There is a positive relationship between investments in communities of practice focused on SSM knowledge accumulation and the extent to which SSM practices are incorporated in the succeeding internal network of practice.

In terms of sequences, the phase of management intervention and the related infrastructural investments that occurred in both case companies has had considerable impact on resulting SSM practices. Internal resources, skills and support are needed to make SSM proactive (Hoejmose and Adrien-Kirby, 2012) and in our cases to transform SSM into a larger, company-wide approach (see Fig. 2). Two major examples of infrastructural investments are (i) the internal support structure and (ii) the public announcement of and external communication about SSM and its targets. Both companies have designed a dedicated infrastructure to pay special attention to commitment and communication across the organization during the company-wide roll-out. Such dedicated investments actually address the challenges that sustainability initiatives face due to resistance by employees in various functional areas across the organization (Gattiker and Carter, 2010). The public setting of targets concerning sustainability criteria is a vital mechanism for guaranteeing sustainability results to the outside world, especially for socially relevant themes (Smith, 2009).

Pioneers and leaders involve and assign other actors to work on this infrastructure. For instance, employees are assigned to facilitate the roll-out; in addition, external (sustainability) experts have advisory roles. The employees who are assigned to facilitate the roll-out are part of the internal infrastructure for the company-wide consolidation of SSM. A particular category of assigned actors are external experts, who often play a legitimacy-enhancing role. Management innovators need to reinforce the legitimacy of the new practice in order to make it acceptable within the organization (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). In the case of SSM, with its important societal aspects, legitimacy in the eyes of the outside world is vital as well. During the first stage, experts may provide advice on new processes and structures, while for the company-wide roll-out they provide external validation (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). Hence, the dedicated infrastructure, which includes hired personnel (like experts), enables and facilitates SSM as a management innovation internally, but especially externally as well. Legitimacy in the eyes of the outside world is further reinforced by the public announcement of targets and by ongoing communication efforts to the outside world, which is a distinct infrastructural investment in itself.

In summary, a company's efforts to implement company-wide SSM practices to meet publicly set targets, requires an infrastructure capable of dispersing SSM throughout the organization and of communicating about it internally and externally. We therefore advance the following proposition:Proposition 3 Investments in a dedicated infrastructure via [1] an internal support structure and [2] public target setting are prerequisites for embedding SSM practices in a company-wide internal network of practice.

Finally, Fig. 2 presents the case companies’ innovation sequences, key actors and scope (organizational entities involved, the role of knowledge, infrastructure and resulting practices) per stage of the SSM management innovation process. In line with Tallman and Chacar (2011), the ‘bubbles’ in the middle of this overview reinforce the crucial role of management intervention in the transition from CoPs to an INoP.

Managerial implicationsOur proposed SSM management innovation model, as shown in Fig. 2, has several managerial implications. First of all, the importance of initial investments in CoPs for later practices indicates that such initial work should be facilitated and fostered. Leaders should be open and receptive to pioneers’ work. Additionally, in subsequent phases, the managerial intervention of setting targets should be accompanied by infrastructural investments in SSM within the company, but also across company borders (related to supply chain partners). This requires, for instance, the involvement of internal and external experts, the training of employees and suppliers and a cross-border support structure.

Second, the precondition that a transition to company-wide SSM requires collaborative skills also has implications for practice. These skills might have been expected to be in place already within our exemplar case companies, for example as a basis for SCM or R&D, and yet they appeared to be a critical improvement area. This may prompt managers who are aiming to develop their SSM processes, to reconsider internal collaborative skills and the profiles of employees working on SSM and to offer training or to attract new people. Such collaborative capabilities support, next to SSM, other organizational capabilities as well.

Third, not all organizations considering SSM have the same capabilities and resources as the organizations in our case studies. Still, we feel that other, smaller types of organizations can still apply parts of it. For instance, even if an organization does not “develop” (as the case companies did in their CoPs) but instead “adopt” knowledge (Crossan and Apaydin, 2010) about SSM for company-wide application, it will still need to invest in an infrastructure in order to communicate and implement these adopted practices. And although supply management and collaboration might have a different position in organizations which do not carry out physical production internally, the required changes to move over to SSM will need internal and, in many cases, external collaboration as well, albeit in different respects and varying intensities.

Discussion and conclusionsOur process studies on two exemplar case companies advance our understanding of the emergence and internal diffusion of SSM, its sequences and its impact. These actual processes of SSM emergence and innovation are understudied in the growing body of literature on SSM (see Carter and Easton, 2011; Sarkis et al., 2011; Touboulic and Walker, 2015), despite its potential impact on the adoption SSM practices. In this process study we connect two areas of research (SSM and management innovation), identifying SSM innovation sequences in two exemplar companies.

This process study contributes to SSM literature in different ways. Firstly we provide process insights through the sequences model which goes beyond the narrow research focus on the implementation of codes of conduct (Hoejmose and Adrien-Kirby, 2012). The sequences model outlines the emergence of CoPs which transform to an INoP and the distinctive roles of key actors like pioneers and leaders throughout those sequences. For this transformation from CoPs to an INoP enabled by management intervention (cf. Tallman and Chacar, 2011) (Proposition 1), it is found that tacit knowledge is required about both internal cross-functional collaboration and external inter-firm collaboration.

Secondly, the influence of management innovation processes on SSM practices has been elucidated in several ways, proposing (Proposition 2) that the depth and scope of small scale knowledge development in CoPs are related to scope in the resulting INoP with its companywide practices. Moreover, investing in the development of a management supported infrastructure is required to enable that small scale (CoP) becomes full scale (INoP), as reflected in our third proposition.

Next, there is also a contribution to management innovation literature. Phenomena like CoPs evolving into INoPs (Tallman and Chacar, 2011), and the important role of human agency have been acknowledged in the innovation literature. Our research, however, adds specific insights of a SSM process study, meeting calls for studies looking into the process of creation and implementation of management innovation (Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009). Our empirical study shows the importance of human agency beyond the role of leaders, which has mainly been emphasized in literature (D’Amato and Roome, 2009; Vaccaro et al., 2010). Rather than internal and external agents (Birkinshaw et al., 2008), we recognize ‘key actors’ who initiate innovations and actors who are assigned (both internally and externally) to support the innovation process. Our study also reveals the importance of the public announcement of SSM targets (as part of the management supported infrastructure), which are not normally observed in management innovation studies and are related to SSM's societal relevance, since public interest creates pressure (Smith, 2009). These announcements enable public societal scrutiny, which is an important medium for monitoring the realization of the communicated sustainability targets and hence firm performance in this area (Zott, 2003).

Among the limitations of our research is its limited generalizability due to the limited number of cases, the specific type of companies (exemplars), and the development stage of SSM at the time of research. Nevertheless, our cases yielded valuable insights into a small number of supply chains that are experimenting with new directions (Pagell and Shevchenko, 2014). This may help other organizations aiming to further develop their SSM initiatives.

An interesting direction for future research would be to challenge and test our findings and propositions on a larger scale and in other empirical settings, for instance in organizations which adopt new SSM practices rather than develop them.

The enablers of ‘knowing how to collaborate’ were identified as a key area requiring attention during the transition to an INoP, and one in which considerable improvements could be made. This finding is worthwhile to study further since it appears to be counterintuitive; one would expect these collaborative skills to be in place in (exemplar) companies where inter- and intra-collaboration is vital for so many processes.

Finally, sensing market and societal opportunities leads to key actors’ initiatives on SSM innovation (cf. Teece, 2007). This indicates another promising area for future research, namely to address this ‘sensing’ and study what has been the threshold at which senior management intervenes in order to move to an organization-wide SSM approach. Considering the quite similar timing of management innovation in our two cases, societal developments and external stimuli could be taken into account explicitly, alongside internal stimuli.

Categories of questions for the semi-structured interviews are listed, although the interview is not limited to those questions, implying room for different or additional topics. Especially categories III and IV are optional. Terminology and definitions in the area of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) are still diffuse (Crane et al., 2008). Hence, terminology may vary per organization and so per interview. For that reason e.g. CSR and sustainability are often both mentioned.

- I.

General CSR and organization

Has care for CSR/sustainability been assigned to parts of the organization? Is a CSR-department in place?

What managerial commitment toward CSR/sustainability is in place?

What stakeholders (internal and/or external) drive CSR/sustainability developments within the organization?

Are there branch initiatives in relation to CSR, or more specifically SS(C)M initiatives?

How is SCM/sourcing organized?

- II.

SS(C)M

What is meant by [1] SS(C)M in the organization and [2] its objectives?

Are any information documents in place regarding the SS(C)M activities?

Actual activities:

What investments have been made in the area of SS(C)M? What SS(C)M approach is in place (Code of conduct, Audits/evaluation with follow up, Collaboration)? Is the focus on practices of suppliers or does it also include reversed logistics or other innovative SCM approaches?

- •

What timeline was underlying those investments/activities?

- •

How does prioritization of SS(C)M take place (e.g. what categories or suppliers get priority)?

- •

(How) is the pro-active stance stimulated?

- •

With which suppliers are those activities taking place (differentiation on e.g. type of relation or risk profile)? To what part of the chain does it reach (first tier suppliers or further)? To what extent are investments generic for all suppliers and idiosyncratic for specific suppliers? Is supplier development secured for the own organization (isolating mechanisms)?

- •

Is the “People” part of the SS(C)M approach as much developed as the environmental part?

- •

Which part of the spend is out of scope? E.g. NPR? What about risks there?

- •

Do you have benchmarks? In what aspects is your SS(C)M approach different from others?

Organization/actors:

- •

Who has decided on the approach toward SS(C)M? How?

- •

By whom are SS(C)M activities organized? (Purchasing department?) How has this been developed? Since when? Is it integral part of the business or a separate project? Knowledge exchange?

- •

How is SS(C)M progressing? Results? How is it being monitored? What has changed in- and externally?

- •

How is this communicated to stakeholders?

- •

Where are hick ups/challenges in the process?

Future/planned activities:

- •

Is a roadmap in place for SS(C)M?

- •

Is any “broad sustainability” (Sarkis et al., 2010) planned in the area of SS(C)M (explain through examples)?

- •

What capabilities are needed now/in future?

- III.

Sustainability risks from the supply chain (OPTIONAL per interviewee)

- IV.

Supplier relations (OPTIONAL per interviewee)

Coding structure

| Subject | Codes | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General information on the organization(General background information) | ORG- | Organization | Contextual information about the company, its CSR organization and policy, SCM organization and policy |

| ORG-CSR | CSR | ||

| ORG-STRAT | Strategy | ||

| ORG-STAKE | Stakeholders | ||

| ORG-SCM | Purchasing/SCM | ||

| ORG-SUPP.REL | Supplier relations | ||

| Timeline/sequences(First research question on sequences) | TI-1 INIT | TI 1: first initiatives | Time and sequences are central in process studies (Langley et al., 2013) and innovation of management practices (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). • The subcodes TI-1, TI-2 and TI-3 have been added during the coding process. Findings: overviewTable 3 |

| TI-2 CONSOL | TI 2: consolidation/announcement | ||

| TO-3 ROLL-OUT | TI 3: company-wide roll-out & infrastructure | ||

| Management innovation characteristics and requirements(Second research question: diversity of indications for MI process: incl tacit/relational skills/knowledge) | MI-STR | MI: structure/tools | Characteristics and requirements of the SSM innovation: • (To be) innovated tacit skills (MI-TSK) or (to be) innovated structures, tools, procedures (MI-STR) (like e.g. evaluation tools (Klassen and Vachon, 2003) • Inter-organizational relations may provide competitive advantage from a relational point of view (Dyer and Singh, 1998). MI-REL concerns SSM innovations affecting those relations. • Initially codes were in place for broad and small sustainability (Sarkis et al., 2010), those have been non active since broad sustainability was not yet encountered. • Codes have been added for (1) the development process (DEV) regarding meetings, brainstorms, actions to plan for SSM development and (2) organizational ambidexterity (DUAL), covering the continuity of established approaches while planning for new practices (Benner and Tushman, 2003) |

| MI-TSK | MI: tacit skills/behavioral | ||

| MI-REL | MI: relational | ||

| MI-DEV | MI: development process | ||

| MI-DUAL | MI: dual capabilities | ||

| Actors/drivers (Actors & drivers (Second research question: diversity of indications for MI process: incl human agency) | ACT-PION | ACT: pioneers | • Motivation (risk averse or opportunity driven) and drivers potentially affect effectiveness of organizational processes (cf. Kennedy and Fiss, 2009) • The four (driving) roles of different actors as drivers have been added during the coding process as sub-codes. Both internal and external actors play articulated roles in management innovation (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). Findings: overview actorsTable 4 |

| ACT-LEAD | ACT: leaders | ||

| ACT-WORKF | ACT: workforce | ||

| ACT-EXP | ACT: experts | ||

| DR-RISK | DR: risk | ||

| DR-OPP | DR: opportunity | ||

| Focus (Background information) | FO: environm | FO-env | Focus of SSM activities: • Social vs. environmental (while maintaining economic stability) (Elkington, 1998) • Evaluation or collaboration character (Klassen and Vachon, 2003) |

| FO: social | FO-soc | ||

| FO: evaluation | FO-eval | ||

| FO: collaboration | FO-collab | ||

ADDED CODES: ‘new’ codes that were added during the coding process are italic and underlined.

It is useful to note that from the plethora of available terms, we use SSM, also in instances where the articles quoted may have used other related terms.

See: http://www.duurzaamaandeel.nl/medialibrary/235/benchmark-responsible-supply-chain-management-2010; see: http://www.global100.org/annual-lists/2010-global-100-list.html; for the sake of anonymity, we have mentioned only a small selection of qualifications.