Creating and developing a firm-hosted virtual brand community forms part of a relationship marketing strategy; therefore, it makes sense to evaluate its effectiveness in terms of relational outcomes. In an attempt to know how marketers can foster the relationship with the brand through virtual communities, we posit and estimate a model of relational efficacy for a firm-managed Facebook brand page (FBP) in which the brand posts created by the firm influence the behavioural engagement of individual users through the utilitarian and hedonic values derived from their interactive experiences within the FBP. The findings highlight that information posts stimulate user behavioural engagement through the utilitarian experiential route. Aside from any experiential route and adopting a more direct path, interaction posts are the main drivers of engagement behaviour. Image posts contribute towards the perception of utility, but in no way affect engagement. Finally, in order to gain a deeper insight, we explore the moderating effect of user brand purchase intensity on the relations posited in the model.

The marketing landscape is changing. The new marketing environment, dominated to a large degree by the emergence of the Internet and social networks, is imposing a shift from conventional relationship marketing towards a “transcending view of relationships” (Vargo, 2009) or an “expanded view of relationship marketing” (Brodie et al., 2011; Vivek et al., 2012), in which the customer's interactive experiences and “customer engagement” play a central role and in which engaged customer involvement in the firm's activities is more proactive, interactive and co-creative (e.g., Brodie et al., 2011; Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2000).

Virtual brand communities constitute an exceptional research context in which to explore firms’ capacity to produce interactive experiences and promote relational engagement among customers (Relling et al., 2016). In these online spaces, individuals come together around some distinct interest (e.g., a brand) to contact and interact with each other in order to exchange, share and pool resources, such as information, knowledge, experiences, entertainment, socio-emotional support and friendship, through diverse computer-mediated communication systems (e.g., Jin et al., 2010a; Preece, 2001). In this sense, a virtual brand community is, first of all, an “online community based on social communications and relationships” (de Valck et al., 2009, p. 185), a “web of personal relationships” (Rheingold, 1993) or a “fabric of relationships” (McAlexander et al., 2002, p. 38). At the very least, a virtual brand community provides a “social structure to the C2C relationship in the consumer-brand-consumer triad” (Wu and Fang, 2010, p. 573).

With the rapid diffusion and widespread use of social network sites (SNS), more and more firms are investing in SNS-based brand communities to build relationships and to encourage users to exchange knowledge about their experiences with the brand or the firm (Ruiz-Mafe et al., 2014). Millions of consumers are connected to their favourite brands through social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and others (Statista, 2016). Unfortunately, this in no way means that all these communities are successful and that all their individual members are active participants. The report by Hampton et al. (2012) on The Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project concludes that, on average, Facebook users “get more from their friends on Facebook than they give to their friends” and that the typical Facebook user is “moderately active” in performing specific Facebook activities. Such results concur with the findings obtained by Gummerus et al. (2012, p. 870), Pöyry et al. (2013, p. 232) and van Varik and van Oostendorp (2013, p. 456), amongst others, in the case of virtual brand communities. In fact, by adopting a naive technically-oriented approach and by paying insufficient attention to the social interactions required to build a true community, many initially attractive online communities may have failed to retain and enduringly engage their members and, not surprisingly, as a result have become “cyber ghost towns” (Preece, 2001). In any case, regardless of its level of success, what makes a company's social site (such as a company-hosted Facebook page) recognizable as a community is that it is a structured set of social relationships among members that share a common interest, i.e., they are admirers of a brand (e.g., Cvijikj and Michahelles, 2013; Pöyry et al., 2013; Zaglia, 2013; Munnukka et al., 2015; Relling et al., 2016).

Given such a general framework, our research focuses on the relational context defined by a Facebook-page brand community (which is founded, managed, and controlled by a firm) in order to pinpoint the key drivers of user brand-page engagement (as a good indicator of community success). Specifically, our research question is how marketers can reach customers and stimulate their community engagement in the Facebook page context. Thus, we centre on those determinants of relationship marketing strategy success in Facebook that can be directly controlled by the firm, such as so-called “brand posts”. The present work seeks to estimate a relational efficacy model of a Facebook brand page (henceforth, FBP), which will allow us to (1) gauge the extent to which brand posts (henceforth, BP) or posts created by the firm running the Facebook page help improve page users’ overall relational experience and, through this indirect pathway, actually serves to foster user engagement behaviour and (2) ascertain whether the orientation or content type of BP can determine the kind of experiential value (utilitarian or hedonic) obtained by the users and their level of page engagement. We thus explore the degree to which each type of BP encourages user brand-page engagement through the utilitarian and hedonic experiential routes. In addition, we explore the moderating influence which the user's brand purchase intensity (i.e., how much of the brand they buy) might have on the model's structure and paths, one aspect not to taken into account thus far in the context of FBP relational efficacy.

Previous literature on the context of FBPs has empirically analyzed the response of page users to brand posts. For instance, de Vries et al. (2012), Cvijikj and Michahelles (2013), Sabate et al. (2014) and Luarn et al. (2015), amongst others, examine how the content type (among other characteristics) of a BP directly impacts on the “popularity” of that BP (as indicated by the number of likes, comments and shares on the BP). Compared to the works mentioned, our research evidences two significant differences in terms of approach and methodology which should be highlighted.

First, while the unit of analysis of previous works is the BP, the unit of analysis in the current work is the brand page and the page-user behaviour. Our research focus is customer behaviour in the relational context of a virtual brand community, in which each individual member holds links with the community as a whole, with the other members of the group, with the brand and with the firm (McAlexander et al., 2002). The dependent variable in our model is not, therefore, the community's direct and global response to each BP or the efficacy per brand post, but each user's overall response to the brand page (i.e. user brand-page engagement) or the relational efficacy per page user. Moreover, contrary to previous works, which evaluate objective indicators of BP content type and engagement, the independent variables in the current research correspond to users’ appraisals vis-à-vis the interest aroused in them by various types of BP depending on their content, and the dependent variable is the users’ subjective evaluation of their active involvement in the page's relational activities. In other words, we measure the number of likes, comments and shares per page-user, not as an objective figure, but rather as the user's subjective evaluation of their actual behaviour.

Secondly, we conjecture that BPs do not promote user engagement directly. Rather, BP content influences user engagement and brand page success through a key mediating construct: the user's brand-page experiences. We thus follow the recommendation of Brodie et al. (2011), Gummerus et al. (2012) and Malthouse and Calder (2011), according to which the engagement construct should be based on the relational experiences of individuals interacting with the brand page. Therefore, we develop an alternative (but fully compatible and complementary) model in which user relational experiences within the FBP play a central and crucial role as a mediator in the relationship between BP interest and user brand-page engagement. In this vein, we refer to the “experiential route of user behavioural engagement”.

In summary, the current paper contributes to the literature on the relational efficacy of SNS-based brand communities. By adopting a different perspective, it analyses the individual users’ experiential and behavioural responses to a FBP and then explains its efficacy per page-user. In addition, the study offers insights about the way in which the firm-generated content can foster users to participate in the FBP activities. The empirical findings show that the utilitarian experiential route clearly dominates the hedonic route. Thus, brand-related content posted by firm ultimately results in active engagement with the FBP if users perceive it as truly useful in solving problems and making decisions. Contrary to expectations, entertainment content, even if appreciated and enjoyed by users, does not promote their active participation. Anyway, while the experiential route is perhaps the most consistent with the relationship marketing orientation, it is not the only (nor the shortest) route of user brand-page engagement.

Theoretical background and research hypothesesUser brand-page engagement as an indicator of relational successDigital technology applications may supply the relational online space, but member-generated content and interpersonal communication provide the essence (Hagel and Armstrong, 1997; Ridings et al., 2002; Wu and Fang, 2010) as well as the formative and shaping force (Bagozzi and Dholakia, 2002) of a virtual brand community. In other words, the value of a virtual community stems from the content produced and shared during member interaction and conversation (Jin et al., 2010a). In light of this, the active and ongoing participation (i.e., engagement) of each member in the community's public forum is regarded as a key ingredient in weaving the relational fabric of a virtual brand community (Rheingold, 1993; Rothaermel and Sugiyama, 2001) and crucial to ensuring the community's survival and endurance (Algesheimer et al., 2005; Koh and Kim, 2004). In addition, creating and developing a firm-hosted community forms part of a relationship marketing strategy (e.g., Pitta and Fowler, 2005; Rothaermel and Sugiyama, 2001), so it makes sense to evaluate the efficacy of a virtual brand community in terms of relational outcomes. Since a brand community brings together individuals around a brand as a focal point for their interests and discussions, individuals’ community engagement will also be perceived by the firm running the community as a reliable indicator of how successful its relationship marketing strategy is (Wiertz and de Ruyter, 2007).

Although there are many and wide-ranging definitions of engagement (see Brodie et al., 2011; Dessart et al., 2015; Hollebeek et al., 2014; van Doorn et al., 2010 or Vivek et al., 2012 for a review of relevant literature), broadly speaking, engagement may be conceived as the intensity of an individual's connection and interaction with a particular object, activity, agent, idea, value or symbol. In the customer relationship marketing context, the “engagement subject” (i.e., the engaged individual) may be either a current customer or a potential customer, and the “engagement object” may refer to a brand or product, an organization's offering or activity, or the others in the social network (e.g., a brand community) created around the brand, product, offering or activity (Vivek et al., 2014). Customer engagement is based on the existence of focal interactive customer experiences with the specific engagement object (Brodie et al., 2011), reaches “beyond purchase” (MSI, 2010, p. 4) and embraces the customer's overall participation within and outside the specific exchange situations (Vivek et al., 2012). Finally, customer engagement is characterized by its dynamic and interactively generated nature (Hollebeek et al., 2014) as well as by its complex multidimensional structure (Brodie et al., 2013), which comprises relevant cognitive, affective, behavioural and social components (Vivek et al., 2012).

In the current research, our interest focuses on the social-behavioural dimension of customer engagement, known as “customer behavioural engagement” (e.g., Gummerus et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2015) or “customer engagement behaviour” (e.g., van Doorn et al., 2010). Specifically, in the case of a Facebook brand page (FBP), users’ behavioural engagement is manifested through their active participation in the functionalities Facebook offers (Gummerus et al., 2012; Luarn et al., 2015): clicking, liking, commenting and sharing behaviours (Wallace et al., 2014), which we term “user brand-page engagement”.

Effect of brand posts on user brand-page engagement by the experiential routeIn the literature relating to the determinants of customer's integration and active participation in social networks and online communities, there are two main streams of research although distinguishing between them does not always proves an easy task. The first group encompasses studies which focus on the role of the “benefits sought” (Cotte et al., 2006) as factors which determine community user behaviour (e.g., Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004; Liao et al., 2013; Pöyry et al., 2013), by considering that the pursuit of these benefits is the main motivational driver of behaviour. Closely linked to this, the other group of works (e.g., Dholakia et al., 2004; Jin et al., 2010a,b; Mathwick et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2013) centres on community members’ relational experience and the “benefits derived” from their integration in the social network as determinants of their behaviour. The present work is framed within this second category.

Following Malthouse and Calder (2011), Gummerus et al. (2012, p. 871) indicate that “customer engagement can only be understood through customer experiences, which are context-dependent”. Engagement occurs by virtue of firsthand interactive experiences (Brodie et al., 2011; Hollebeek et al., 2014; van Doorn et al., 2010) and its behavioural manifestation reflects individual involvement and participation in activities. Thus, although individual users’ initial intention to join a virtual community is influenced by their value expectations, over time the accumulation of community experiences shapes their community behaviour. Cleary, the reason why members actively participate in a virtual community is attributed to the experiential values derived from their relationship history within the community.

Adapting the Brakus et al. (2009) definition of brand experience to our case study, the user's brand-page experience is a term employed to represent the cognitive and affective reactions sparked in the user by page-related stimuli. Page experience occurs during the whole process of interaction with the FBP and stems from the set of interactions involving the user over time. This is not, therefore, a one-off experience (e.g., a short-lived emotion) brought on by a particular stimulus (e.g., a BP), but an overall relational experience resulting from an accumulation of interactive experiences. Insofar as the relational experience itself can be more or less rich in value, users evaluate the overall experience in terms of the benefits it provides. Experiential value thus emerges as a consequence of cumulative experiences.

By joining a virtual community, users may obtain different types of relationship benefits (i.e. benefits resulting from integration), such as practical benefits, social benefits, social enhancement, entertainment and economic benefits (Gummerus et al., 2012), or different types of values, such as purposive (including informational and instrumental) value, self-discovery, maintaining interpersonal connectivity, social enhancement and entertainment value (Dholakia et al., 2004). Reflecting the utilitarian versus hedonic dichotomy (Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982), Mathwick et al. (2001) conceptualize the “experiential value” within the context of online purchasing and distinguish between an intrinsic or hedonic component (e.g., visual appeal, entertainment, escapism and enjoinment) and an extrinsic or utilitarian component (e.g., service excellence, efficiency and economic value). In the case of virtual communities (Dholakia et al., 2004; Jin et al., 2010a), the extrinsic experience is linked to the purposive or utilitarian value, that is, to the informational and instrumental benefits derived from accessing information on the product and its uses, solving specific problems, and learning from others. In contrast, the intrinsic experience is linked to the social hedonic or entertainment value derived from searching for playfulness, fun, amusement, fantasy, sensory stimulation or relaxation by interacting with others. As an active source of intrinsic value, playfulness involves enjoyment and escapism, and is reflected in the pleasure that comes from engaging in activities that are absorbing and provide an opportunity to get away from daily routine (Mathwick et al., 2001).

In both utilitarian and entertainment experiential dimensions, if community members are not satisfied, there will be no incentive to participate (or to continue participating) in the community. On the contrary, if individual members’ experiences in previous interactions within the community prove positive, they will feel satisfied and motivated to participate (or to participate more actively) in the community activities (Casaló et al., 2010). In this line of thought, Jin et al. (2010a) evidence the influence of positive disconfirmation of both utilitarian and hedonic experiential values on individual member satisfaction and affective commitment and, in turn, on “continuance intention to participate” in an online community. Likewise, Loureiro et al. (2015) note how a satisfied member is more willing to engage deeply.

This effect of positive experiences on active participation might also be explained as the result of “the call of duty” (Wiertz and de Ruyter, 2007) or a sense of indebtedness (Chan and Li, 2010), according to which community members tend to reciprocate the social support received. Jin et al. (2010b) show that, in return for the social and functional benefits gained from community participation, members reciprocate with their affective and calculative commitment to the virtual community. In our case, users who gain utilitarian and hedonic experiential values by participating in the FBP are more likely to reciprocate. In this regard, active engagement is understood as a reciprocating behaviour to reduce the sense of indebtedness. Furthermore, participation may also be due to patterns of imitation and contagion. Based on observational learning theory, Zhou et al. (2013) explore the transformation mechanism that converts visitors into active members in online brand communities. If, by viewing posts, visitors realize the benefits of active member participation and perceive posts as having informational and social values, they will be interested in imitating member behaviour and in seeking greater belongingness to the community through a stronger intention to participate. Finally, in line with the flow theory (Novak et al., 2000), if community users experience “flow” in their online interactions (more likely when they are involved in enjoyable activities that provide them with utility and entertainment), they will be more inclined to spend time and effort in contributing to the community. In fact, Hall-Phillips et al. (2016) report a direct and positive link between escapism and engagement in social networks.

All of this drives us to advocate the experiential origin of engagement and suggest a positive direct effect of the experiential value obtained on the level of engagement expressed by page users. In turn, users’ experiential value comes from connecting to a brand page and stems from the global evaluation of their relationship history within the community (i.e., their experiential history of interaction with the brand, the firm and other page-users). Even so, in this process of producing both utilitarian and hedonic experiential values, page posts play a particularly key role. When users are exposed to Facebook page posts, the elicited affective and cognitive elaborations determine attitudes towards the posts (Chen et al., 2015), which are later transferred to experiences and perceptions of experiential value. As a result, the interest which users perceive in the page posts will determine the quality of their relational experience with the brand page.

It is clear, however, that Facebook-page posts can be generated by both marketer and peer user. Thus, depending on the post creator, posts can be categorized as either “brand post” or “user post”. Unlike user-generated content (i.e. user posts), brand posts (BPs) refer to the content created and directly controlled by an identified marketer (or brand) under the tenet of viral marketing (Chen et al., 2015). Through these posts, the firm seeks to influence page user experiences. Yet, BP content may vary enormously and not all BPs generate the same values to the same degree. According to Luarn et al. (2015), marketers can post information about the product, firm, brand or marketing activities (informational posts); messages presenting limited offers, samples, coupons, special offers and other campaign activities aimed at promoting the brand (remuneration posts); questions, opinion polls and other messages encouraging users to discuss, interact and actively participate on brand pages (social posts), or content that is unrelated to the brand or a particular product, but provides an opportunity for users to enjoy themselves, have fun and escape routine (entertainment posts). Assuming, therefore, that BPs are designed to offer a range of benefits (e.g., entertainment or firm- and brand-related information) or to spark an array of different responses, the interest which such content arouses is expected to shape user experience in the FBP and the type and level of experiential value to emerge.

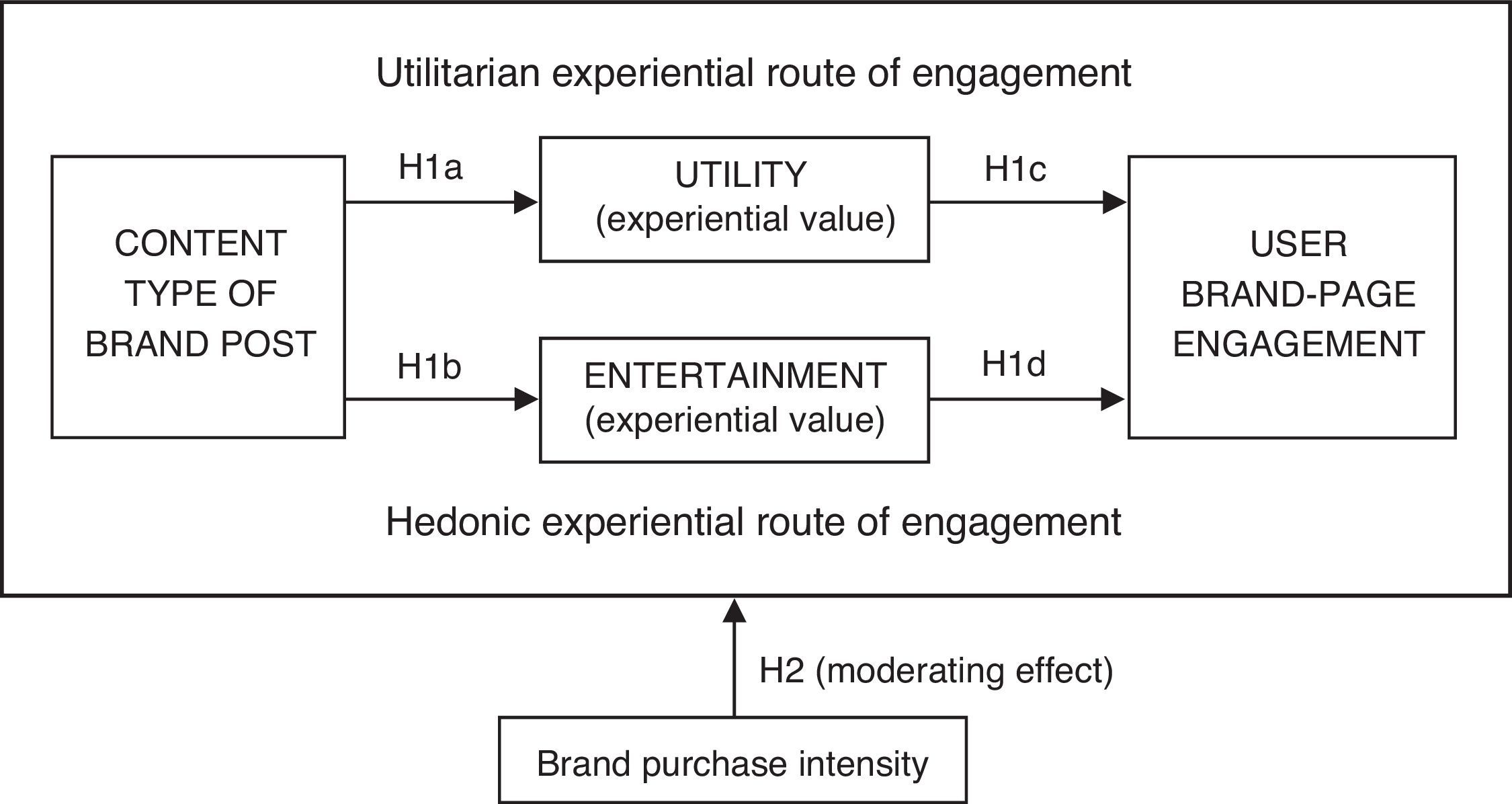

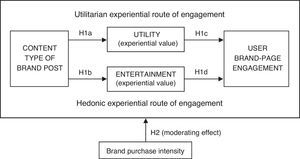

Taken together, the preceding arguments suggest that experiential value mediates the effect of brand posts (BPs) on users’ page engagement behaviour. The distinction between “utility” and “entertainment” as experiential values leads us to consider the possible two-fold influence of BPs on user behavioural engagement. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 1, we propose two experiential routes of active engagement: the utilitarian route, which derives from informational value, and the entertainment route, which derives from enjoyment and escapism values. Such a consideration of experiential values as mediating variables entails the assumption that (1) BPs are factors inducing experiential value and (2) active engagement is a behaviour induced by experiential values. Accordingly, the following hypothesis (broken down into more specific and operational sub-hypotheses) is submitted for empirical testing:H1 On a FBP, experiential value mediates the influence of brand posts on a user's page engagement behaviour, inasmuch as brand posts contribute towards the perception of both utilitarian (H1a) and hedonic (H1b) experiential values (albeit differently, depending on the orientation or content type of brand posts) and, in turn, the perception of both utilitarian (H1c) and hedonic (H1d) experiential values contributes positively to a user's page engagement behaviour.

Given that the present study focuses on analysing the experiences and engagement of individuals who display a positive attitude towards the brand (inferred because they are fans of the brand page) and who also tend to purchase the brand, we were keen to find out whether the amount they purchase in any way influences the effects considered. Empirical evidence has shown that more intense purchasers are more engaged and maintain more stable and longer-lasting relations with the firm (e.g., Reinartz and Kumar, 2003). In the present context, we might also speculate that brand purchase intensity could affect page-users’ perceptions, attitudes and behaviours and, therefore, might influence the extent to which interacting with the BPs generates utility or entertainment and, in turn, fosters engagement.

As regards the effect of the type of BP on the perceived experience (H1a and H1b), it could be argued that more intense purchasers, thanks to their greater brand purchase and consumption experience, are more familiar with the brand and with the firm's products and, therefore, perceive less utility in posts that offer informative content. Should this be the case, the effect of informational posts on utilitarian value will be less, the higher the purchase intensity (negative moderating effect on H1a). Yet, regular buyers of the brand might also be thought to be more sensitive to the latest information on the firm's products and its innovations, which would allow us to conjecture the opposite informational post effect to the one suggested earlier (i.e., a positive moderating effect on H1a). Similar observations might also be made with regard to other kinds of BPs and the other type of experiential value.

Likewise, it is also possible to put forward contradictory hypotheses for the moderating effect of purchase intensity on the relations suggested in H1c and H1d between experiential values and engagement. On the one hand, it seems reasonable to consider that the most intense purchasers will be more engaged with the brand and will, therefore, be more inclined towards page engagement irrespective of how they evaluate their experience in the FBP. In such instances, page engagement would be shaped less by experiential values when the user is a more intense purchaser (negative moderating effect on H1c and H1d). Nevertheless, it might also be argued that purchasers who are more intense and involved with the brand behave motivated more by the call of reciprocity and, therefore, adjust their engagement behaviour better to the level of value they receive. By contrast, purchasers who are less intense and less involved with the brands might act less motivated by reciprocity and more by opportunism, leading them to display a lower level of engagement with the page, somewhat irrespective of the value received. In this case, the positive effect of the experiential value on page engagement will be clearer for more intense purchasers (positive moderating effect on H1c and H1d).

Since we put forward this purchase-intensity effect as an exploratory question, we will test empirically for the moderating effect, but do not posit a specific directional hypothesis.H2 The page-user's brand purchase intensity moderates the direct and indirect effects considered in hypothesis H1, i.e., the direct influence of BP on experiential value, the direct influence of experiential value on engagement, and the indirect influence of BP on engagement.

All the proposed relations are shown in Fig. 1.

DataSampleThe information required to estimate the model and to test the hypotheses was taken from a sample of fans in a Facebook page of a Spanish brand of women's fashion run by the firm itself. The fashion brand, which wishes to remain anonymous, currently boasts some 27,000 Facebook fans. Although the brand is commercialized in different European countries, the fan page is addressed to Spanish customers (it is in Spanish).

The fashion industry is unquestionably one of enormous importance when analysing the value of online communities for brands (e.g., Park and Cho, 2012; Christofer, 2014), given that many communities and blogs run by the brands themselves or by fashion lovers have emerged in recent years. Moreover, clothes are experiential products with emotional connotations in addition to their utilitarian functions (Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982). The fan pages of the brands are thus likely to offer followers the chance to find both hedonic and utilitarian experiences. In the case of the Facebook page chosen for the present study, the content generated by the firm (BP) includes catalogue photos, descriptions of clothes, information on promotions, ideas for matching clothes and accessories, “the making of” videos, photos of fans and famous people wearing the brand's clothes, opinion polls about new designs, prize draws amongst fans as well as invitations to take part in activities organized by the page, information concerning the brand's presence at fairs and fashion shows together with appearances in the social media (television, magazines or blogs), etc. On said brand page, the firm does not post messages that do not refer to the firm or the brand, in reference to the type of content which Cvijikj and Michahelles (2013), de Vries et al. (2012) or Luarn et al. (2015) term as “entertainment posts”.

In order to gather information, a link to an online questionnaire was inserted in a post of the Facebook fan-page. In an effort to encourage people to reply, fans were offered a 10 Euro voucher for their next online purchase. We obtained 266 responses. Since the firm disposed of the emails address provided by respondents, it was noted that some individuals submitted the questionnaire twice. After deletion of duplicated answers, a final sample of 252 responses was accepted for analysis. Given that those surveyed chose themselves when responding, the sample cannot be considered representative. Nevertheless, we feel that it is a valid sample for studying the behaviour of the most active followers and those most closely linked to the brand. Even though the sample is not random, we calculated the sampling error and obtained a value of 6.13% for a confidence interval of 95%, a finite population size (19,895 fans) and a sample of 252 interviewees.

As regards the description of the sample in terms of sex, age, qualifications and occupation, all of those who answered were women, 52% were aged between 36 and 45, 69% held a university degree and 71% were salaried workers, reflecting fairly well the profile of the brand's purchasers. As for their purchase behaviour, over the past year, 33% had bought over four of the brand's garments, 37% between two and four, 17% only one and 13% none. Finally, with regard to where they preferred to buy the brand, 52% stated a preference for the physical store and 48% for the online store.

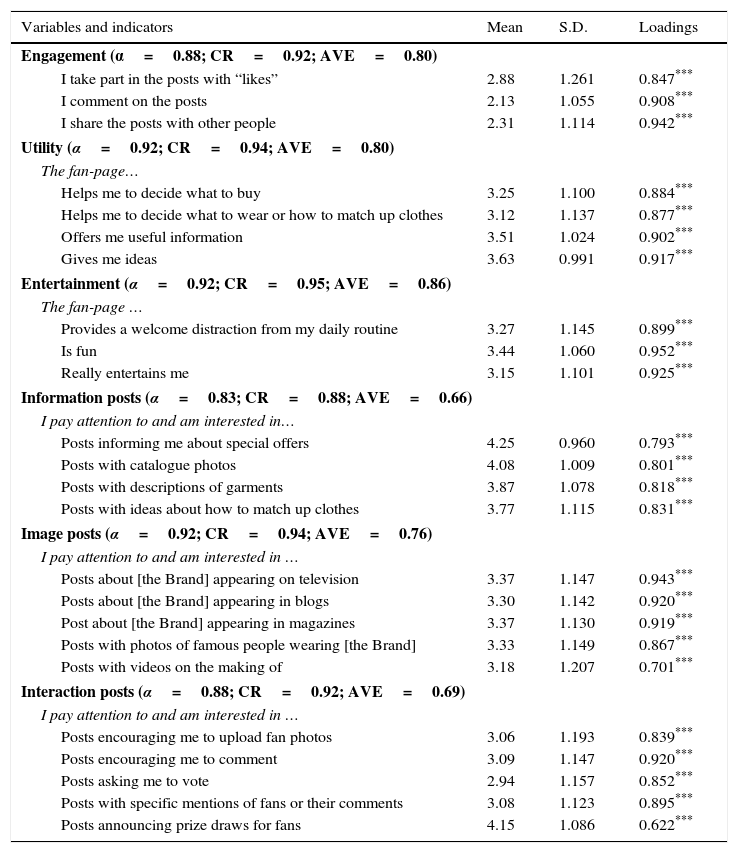

MeasuresMeasurement of the variables (Table 1) is based on a review of the literature and on the scales validated in prior research, although some variables had to be adapted to the context of the study. Except for the number of brand articles purchased, all items were measured on 1 to 5 point Likert type scales. User brand-page engagement was measured using three indicators reflecting the frequency (from 1: virtually never, to 5: quite often) with which those surveyed engaged with the brand page through the three options offered by Facebook: like, comment and share (e.g., Cvijikj and Michahelles, 2013; Luarn et al., 2015). Although these indicators reflect different behaviours, they are usually closely related, and so were treated as reflective items. As regards user experiences in the social network, the hedonic experiential value (i.e., entertainment) was measured with two indicators of enjoyment and one indicator reflecting escapism used by Mathwick et al. (2001), whereas the utilitarian experiential value (i.e., utility) scale was based on previous scales of perceived utility (e.g., Davis et al., 1989; Kulviwat et al., 2007) but adapted to the case of a fashion social network.

Variables measured.

| Variables and indicators | Mean | S.D. | Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement (α=0.88; CR=0.92; AVE=0.80) | |||

| I take part in the posts with “likes” | 2.88 | 1.261 | 0.847*** |

| I comment on the posts | 2.13 | 1.055 | 0.908*** |

| I share the posts with other people | 2.31 | 1.114 | 0.942*** |

| Utility (α=0.92; CR=0.94; AVE=0.80) | |||

| The fan-page… | |||

| Helps me to decide what to buy | 3.25 | 1.100 | 0.884*** |

| Helps me to decide what to wear or how to match up clothes | 3.12 | 1.137 | 0.877*** |

| Offers me useful information | 3.51 | 1.024 | 0.902*** |

| Gives me ideas | 3.63 | 0.991 | 0.917*** |

| Entertainment (α=0.92; CR=0.95; AVE=0.86) | |||

| The fan-page … | |||

| Provides a welcome distraction from my daily routine | 3.27 | 1.145 | 0.899*** |

| Is fun | 3.44 | 1.060 | 0.952*** |

| Really entertains me | 3.15 | 1.101 | 0.925*** |

| Information posts (α=0.83; CR=0.88; AVE=0.66) | |||

| I pay attention to and am interested in… | |||

| Posts informing me about special offers | 4.25 | 0.960 | 0.793*** |

| Posts with catalogue photos | 4.08 | 1.009 | 0.801*** |

| Posts with descriptions of garments | 3.87 | 1.078 | 0.818*** |

| Posts with ideas about how to match up clothes | 3.77 | 1.115 | 0.831*** |

| Image posts (α=0.92; CR=0.94; AVE=0.76) | |||

| I pay attention to and am interested in … | |||

| Posts about [the Brand] appearing on television | 3.37 | 1.147 | 0.943*** |

| Posts about [the Brand] appearing in blogs | 3.30 | 1.142 | 0.920*** |

| Post about [the Brand] appearing in magazines | 3.37 | 1.130 | 0.919*** |

| Posts with photos of famous people wearing [the Brand] | 3.33 | 1.149 | 0.867*** |

| Posts with videos on the making of | 3.18 | 1.207 | 0.701*** |

| Interaction posts (α=0.88; CR=0.92; AVE=0.69) | |||

| I pay attention to and am interested in … | |||

| Posts encouraging me to upload fan photos | 3.06 | 1.193 | 0.839*** |

| Posts encouraging me to comment | 3.09 | 1.147 | 0.920*** |

| Posts asking me to vote | 2.94 | 1.157 | 0.852*** |

| Posts with specific mentions of fans or their comments | 3.08 | 1.123 | 0.895*** |

| Posts announcing prize draws for fans | 4.15 | 1.086 | 0.622*** |

*p<0.05 (bilateral).

**p<0.01 (bilateral).

To pinpoint content types of BPs, 15 items were proposed reflecting the various content offered by the firm on its Facebook page and which was rated by fans in terms of the interest said content generated in five-position scales ranging from 1 (not in the least interesting) to 5 (very interesting). These items were grouped into the three categories that emerged from an exploratory factorial analysis: (1) interaction content/posts or posts that encourage fans to get involved (e.g., uploading photos, commenting or voting); (2) image content/posts or posts that convey the brand's image and social presence (e.g., “making of” videos, the brand's appearance on television, blogs and magazines, or photos and videos of famous people wearing the brand), and (3) information content/posts or posts that provide information about the brand and its products (e.g., catalogue, description of garments and accessories, promotions or ideas for matching up clothes). For the subsequent analyses, the item relating to “prize draws”, which factorial analysis located in the factor we referred to as “information content/posts”, was relocated to the factor “interaction content/posts”. This is because in the page analyzed, the prize draws appear as an incentive to take part or as a reward for users who engage in the page by liking, sharing or commenting. Finally, brand purchase intensity was measured as the number of garments purchased over the last year on a four-point scale: (1) no purchase, (2) one garment, (3) between two and four garments and (4) more than four garments. This variable was dichotomized so as to create two user groups: lower-intensity (LI) group, comprising the 76 fans who purchased one or no garments, and higher-intensity (HI) group, made up of the 196 fans who purchased two or more garments.

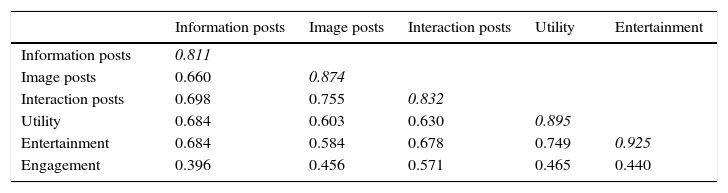

Table 1 shows the indicators used and the descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) of each indicator, as well as the standardized factorial loadings in the measurement model to emerge from partial least squares analysis (PLS). Also offered are Cronbach's alpha coefficient, composite reliability (CR) and the average variance extracted (AVE) of each reflective construct. Table 2 shows the correlation matrix as well as the square root of the AVE in order to test the discriminant validity of the proposed variables following the criterion of Fornell-Larcker. A high correlation can, however, be seen between the two dimensions of the experiential value (utility and entertainment). Although they are different concepts and are not expected to be highly correlated, in the current context (fashion fans) we suspect that utility and entertainment might act as reflective dimensions of an experiential value construct. To check this, we performed Type I second-order confirmatory factor analysis (Jarvis et al., 2003) that confirmed the reflective nature of utility and entertainment as dimensions of experiential value [χ2(13)=32.82, p=0.000, GFI=0.964, AGFI=0.923, CFI=0.987, NFI=0.979, RMSEA=0.078].

Correlation matrix.

| Information posts | Image posts | Interaction posts | Utility | Entertainment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information posts | 0.811 | ||||

| Image posts | 0.660 | 0.874 | |||

| Interaction posts | 0.698 | 0.755 | 0.832 | ||

| Utility | 0.684 | 0.603 | 0.630 | 0.895 | |

| Entertainment | 0.684 | 0.584 | 0.678 | 0.749 | 0.925 |

| Engagement | 0.396 | 0.456 | 0.571 | 0.465 | 0.440 |

The diagonal shows the square root of the AVE of the reflective constructs (all except engagement).

In order to avoid, or at least minimize, common method variance bias, we followed some recommendations made by Podsakoff et al. (2003) when designing the questionnaire: respondents were explicitly assured that there were no right or wrong answers and that the information they provided would be treated confidentially; item wording was revised so as to avoid ambiguous or unfamiliar terms; different response formats were used; and question order did not match the causal sequence in the model. In addition, Harman's single-factor test was performed. Evidence for common method bias exists when a single factor emerges from the factor analysis or when one general factor accounts for the majority of covariance among the measures. In our case, exploratory factor analysis with all the indicators produced five factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0 (accounting for 76% of explained variance) and a first factor explaining only 22% of variance. In sum, the procedural remedies applied and the findings of the above-mentioned test suggest that common method bias is not a major concern in this study.

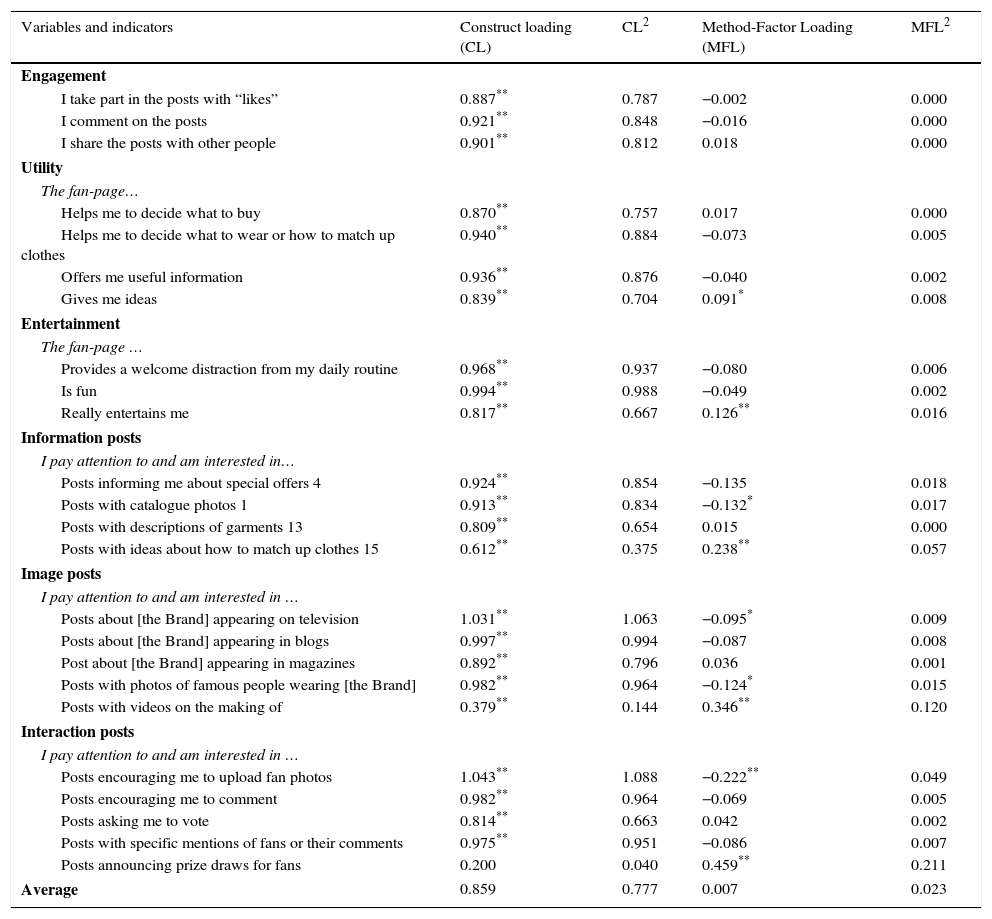

The unmeasured latent methods factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003) was also performed. We introduced a CMV factor that includes all the principal constructs’ indicators and calculated the degree to which each indicator's variance was explained by its principal construct (i.e., substantive variance) and by the CMV factor. While substantive variance averaged 0.777, the average method-based variance is 0.023 (Table 3). As the ratio of substantive variance to method variance is about 34:1, and most of the method factor loadings are insignificant, this analysis also indicates that CMV is unlikely to be a critical factor in the study.

Common method variance analysis.

| Variables and indicators | Construct loading (CL) | CL2 | Method-Factor Loading (MFL) | MFL2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement | ||||

| I take part in the posts with “likes” | 0.887** | 0.787 | −0.002 | 0.000 |

| I comment on the posts | 0.921** | 0.848 | −0.016 | 0.000 |

| I share the posts with other people | 0.901** | 0.812 | 0.018 | 0.000 |

| Utility | ||||

| The fan-page… | ||||

| Helps me to decide what to buy | 0.870** | 0.757 | 0.017 | 0.000 |

| Helps me to decide what to wear or how to match up clothes | 0.940** | 0.884 | −0.073 | 0.005 |

| Offers me useful information | 0.936** | 0.876 | −0.040 | 0.002 |

| Gives me ideas | 0.839** | 0.704 | 0.091* | 0.008 |

| Entertainment | ||||

| The fan-page … | ||||

| Provides a welcome distraction from my daily routine | 0.968** | 0.937 | −0.080 | 0.006 |

| Is fun | 0.994** | 0.988 | −0.049 | 0.002 |

| Really entertains me | 0.817** | 0.667 | 0.126** | 0.016 |

| Information posts | ||||

| I pay attention to and am interested in… | ||||

| Posts informing me about special offers 4 | 0.924** | 0.854 | −0.135 | 0.018 |

| Posts with catalogue photos 1 | 0.913** | 0.834 | −0.132* | 0.017 |

| Posts with descriptions of garments 13 | 0.809** | 0.654 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| Posts with ideas about how to match up clothes 15 | 0.612** | 0.375 | 0.238** | 0.057 |

| Image posts | ||||

| I pay attention to and am interested in … | ||||

| Posts about [the Brand] appearing on television | 1.031** | 1.063 | −0.095* | 0.009 |

| Posts about [the Brand] appearing in blogs | 0.997** | 0.994 | −0.087 | 0.008 |

| Post about [the Brand] appearing in magazines | 0.892** | 0.796 | 0.036 | 0.001 |

| Posts with photos of famous people wearing [the Brand] | 0.982** | 0.964 | −0.124* | 0.015 |

| Posts with videos on the making of | 0.379** | 0.144 | 0.346** | 0.120 |

| Interaction posts | ||||

| I pay attention to and am interested in … | ||||

| Posts encouraging me to upload fan photos | 1.043** | 1.088 | −0.222** | 0.049 |

| Posts encouraging me to comment | 0.982** | 0.964 | −0.069 | 0.005 |

| Posts asking me to vote | 0.814** | 0.663 | 0.042 | 0.002 |

| Posts with specific mentions of fans or their comments | 0.975** | 0.951 | −0.086 | 0.007 |

| Posts announcing prize draws for fans | 0.200 | 0.040 | 0.459** | 0.211 |

| Average | 0.859 | 0.777 | 0.007 | 0.023 |

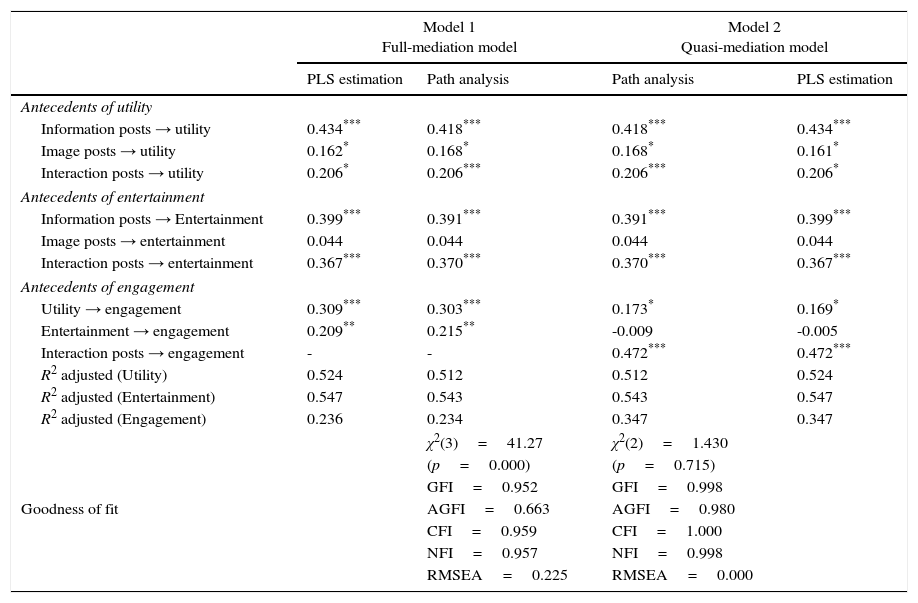

In order to test the hypotheses posited, the partial least squares (PLS) method was applied using SmartPLS (Ringle et al., 2005) software. The levels of statistical significance of the coefficients of the measurement and structural model were calculated using bootstrapping with 500 sub-samples. The results of estimating the structural model (Model 1 or full-mediation model) are shown in the first column of Table 4. In order to test the robustness of the results obtained, each latent constructs was reduced to a single index (as the average of its indicators) and the model was estimated by means of path analysis (using AMOS 23.0 software). Said estimation allows us to consider the reflective nature of the two dimensions of experiential value (allowing the correlation of the measurement errors of utility and entertainment) and to obtain goodness-of-fit indices. As shown in the second column of Table 4, the fit obtained did not prove satisfactory. The full-mediation model was then compared to several nested models considering the direct effects of brand post content on engagement, that is, the partial mediation of the utilitarian and hedonic experiential values in the relationship between type of BP and user engagement. This revealed that introducing a direct effect of the interaction posts on engagement significantly improved the model's goodness-of-fit (third column in Table 4). Lastly, this quasi-mediation model (Model 2) was estimated by means of PLS (fourth column in Table 4). These final results were used to test hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c, and H1d. Despite the high correlation between utility and entertainment, the values of the variance inflation factor (VIF) rule out the existence of problems of multicollinearity between the determinants of engagement, both in the full mediation model [VIF (Utility)=2.274; VIF (Entertainment)=2.274] and in the quasi-mediation model [VIF (Interaction posts)=1.976; VIF (Utility)=2.728; VIF (Entertainment)=2.711].

Results: hypothesized and respecified models.

| Model 1 Full-mediation model | Model 2 Quasi-mediation model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLS estimation | Path analysis | Path analysis | PLS estimation | |

| Antecedents of utility | ||||

| Information posts → utility | 0.434*** | 0.418*** | 0.418*** | 0.434*** |

| Image posts → utility | 0.162* | 0.168* | 0.168* | 0.161* |

| Interaction posts → utility | 0.206* | 0.206*** | 0.206*** | 0.206* |

| Antecedents of entertainment | ||||

| Information posts → Entertainment | 0.399*** | 0.391*** | 0.391*** | 0.399*** |

| Image posts → entertainment | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.044 |

| Interaction posts → entertainment | 0.367*** | 0.370*** | 0.370*** | 0.367*** |

| Antecedents of engagement | ||||

| Utility → engagement | 0.309*** | 0.303*** | 0.173* | 0.169* |

| Entertainment → engagement | 0.209** | 0.215** | -0.009 | -0.005 |

| Interaction posts → engagement | - | - | 0.472*** | 0.472*** |

| R2 adjusted (Utility) | 0.524 | 0.512 | 0.512 | 0.524 |

| R2 adjusted (Entertainment) | 0.547 | 0.543 | 0.543 | 0.547 |

| R2 adjusted (Engagement) | 0.236 | 0.234 | 0.347 | 0.347 |

| Goodness of fit | χ2(3)=41.27 | χ2(2)=1.430 | ||

| (p=0.000) | (p=0.715) | |||

| GFI=0.952 | GFI=0.998 | |||

| AGFI=0.663 | AGFI=0.980 | |||

| CFI=0.959 | CFI=1.000 | |||

| NFI=0.957 | NFI=0.998 | |||

| RMSEA=0.225 | RMSEA=0.000 | |||

In light of the results, it can be confirmed that the content of BPs impacts on the perception of experiential values. In fact, the three kinds of BP account for over fifty per cent of the variability of utility (R2=0.524) and entertainment (R2=0.547). Specifically, in agreement with H1a, the interest aroused by information posts (b=0.434, p<0.001), image posts (b=0.161, p<0.05) and interaction posts (b=0.206, p<0.05) positively and significantly affects the utilitarian experiential value. In agreement with H1b, information posts (b=0.399, p<0.001) and interaction posts (b=0.367, p<0.001) positively and significantly affect hedonic experiential value. However, the same cannot be said of image posts, whose effect on entertainment does not prove significant (b=0.044, p>0.1). Aside from this exception, hypotheses H1a and H1b can be seen to be supported.

In turn, the perception of an extrinsic or utilitarian experiential value significantly contributes to improving fan engagement in FBP, in other words, to enhancing their level of activity by following, commenting on and sharing posts, both in the full-mediation model (b=0.309, p<0.001) and in the quasi-mediation model (b=0.169, p<0.05). In the case of intrinsic or hedonic experiential value, things change. As expected, the result of estimating the full-mediation model (Model 1) evidences a positive and significant effect (b=0.209, p<0.01) of entertainment on engagement. Nevertheless, this effect loses all its power and ceases to be significant (b=−0.005, p>0.1) in the case of the quasi-mediation model (Model 2). We thus find support for hypothesis H1c, but are forced to reject hypothesis H1d. Finally, although it is not an effect which is considered in hypothesis H1 and in the original model, we see how interaction posts have a strong direct impact on engagement (b=0.472, p<0.001). Indeed, this type of BP becomes the main driver of active participation, even above the two dimensions of experiential value.

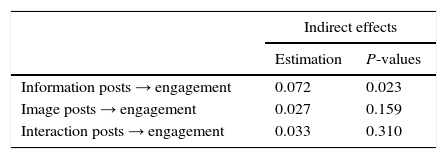

By way of a complement to the results commented on, Table 5 shows the indirect effects of BP type on engagement. As can be seen, only the indirect effect of information posts (b=0.072, p<0.05), whose influence on engagement is mainly noticeable through utilitarian experiential value, proves significant. Even if they generate experiential value, image and interaction posts do not contribute significantly to engagement through the indirect experiential route. Nevertheless, the existence of the previously mentioned direct effect of interaction posts on engagement leads us to conclude that its effect on engagement is immediate, without any intermediation from experience. As a result, we can partially support H1 since we see three types of effects of BPs on engagement depending on the BP content type: (1) a purely indirect effect (not direct) through utility, in the case of information posts; (2) an insignificant effect (both direct and indirect) in the case of image posts, and (3) a purely direct effect (not mediated by experiential values) in the case of interaction posts.

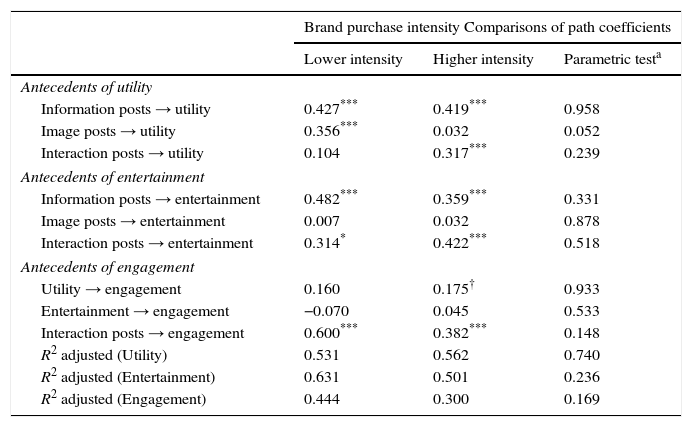

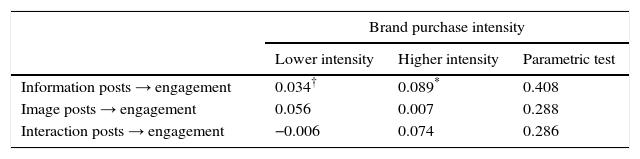

With regard to exploratory hypothesis H2, namely, the moderating effect of brand purchase intensity on the relations posited in H1, we examine the differences between the two groups created with regard to how many of the brand's items were bought (i.e., lower and higher purchase intensity). Table 6 shows the results of the PLS estimation of the multi-group structural model. In order to test H2, we use the parametric significance test provided by SmartPLS for the difference of group-specific path coefficients. The parametric test also allows us to gauge measurement invariance. Across the groups, neither the factor loadings nor the factor weights differ significantly. Configural and metric invariance can thus be confirmed (Steenkamp and Baumgartner, 1998). Finally, Table 7 shows the indirect effects of the three types of BP on engagement for each user group.

PLS multi-group analysis.

| Brand purchase intensity Comparisons of path coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower intensity | Higher intensity | Parametric testa | |

| Antecedents of utility | |||

| Information posts → utility | 0.427*** | 0.419*** | 0.958 |

| Image posts → utility | 0.356*** | 0.032 | 0.052 |

| Interaction posts → utility | 0.104 | 0.317*** | 0.239 |

| Antecedents of entertainment | |||

| Information posts → entertainment | 0.482*** | 0.359*** | 0.331 |

| Image posts → entertainment | 0.007 | 0.032 | 0.878 |

| Interaction posts → entertainment | 0.314* | 0.422*** | 0.518 |

| Antecedents of engagement | |||

| Utility → engagement | 0.160 | 0.175† | 0.933 |

| Entertainment → engagement | −0.070 | 0.045 | 0.533 |

| Interaction posts → engagement | 0.600*** | 0.382*** | 0.148 |

| R2 adjusted (Utility) | 0.531 | 0.562 | 0.740 |

| R2 adjusted (Entertainment) | 0.631 | 0.501 | 0.236 |

| R2 adjusted (Engagement) | 0.444 | 0.300 | 0.169 |

As observed when analysing the sample as a whole (Table 4, model 2), entertainment has no significant impact on engagement in either of the intensity groups (Table 6). However, the effect of utility on engagement, which did prove significant for the sample as a whole (p<0.05), ceases to be so for the LI group (b=0.160, p>0.1) and only proves marginally significant for the HI group (b=0.175, p<0.1). In any case, as the parametric test reveals, inter-group differences are not in the least significant. As regards the effects of experiential values on engagement, the two intensity groups thus follow virtually the same pattern of behaviour, leading us to reject the moderating influence of brand purchase intensity on the relations posited in H1c and H1d.

Once again, as with the previous analysis for the total sample, information posts positively and significantly affect utilitarian value, both in the LI group (b=0.427, p<0.001) and in the HI group (b=0.419, p<0.001), and hedonic value, both in the LI group (b=0.482, p<0.001) and in the HI group (0.359, p<0.001), with no significant differences evident between the two intensity groups (Table 6). In this way, through experiential values, information posts indirectly affect engagement (Table 7), although to an extent and at a level of significance equally as poor as before: b=0.034 (p<0.1), for the LI group, and b=0.089 (p<0.05), for the HI group. As a result, contrary to what was conjectured in H2, brand purchase intensity does not seem to moderate the direct and indirect effects of informational content.

In the case of image posts, the situation differs slightly. As in the general analysis, this kind of branded content does not contribute directly to entertainment value or indirectly to behavioural engagement in either of the two purchase-intensity groups. Nevertheless, the general effect of image posts on the perception of utilitarian value (b=0.161, p<0.05) is now no longer evident in the case of the HI group (b=0.032, p>0.1), but is maintained and even furthered, both in terms of power and level of significance, in the case of the LI group (b=0.356, p<0.001). Moreover, as evidenced by the parametric test, this difference between intensity groups is significant with a confidence level close to 95%, which provides only a very partial support for the hypothesis H2. It would appear that BPs which convey the brand image prove useful for decision making, although only in the case of fans who display lower purchase intensity (i.e. negative moderating effect of purchase intensity on the relation posited in H1a).

Finally, even if no significant differences are apparent between the groups, one comment is worth making with regard to the effects of interaction posts. On the one hand, this type of BP continues to emerge as a clear driver of the entertainment experienced by page-users, both when concerning clients who are not very intense (b=0.314, p<0.05) and those who are more intense (b=0.422, p<0.001). On the other hand, it can be seen how the positive effect of interaction posts on the perception of utilitarian value is less evident in the LI group (b=0.104, p>0.1) and only proves strong and significant in the case of the HI group (b=0.317, p<0.001). Thus, even though we lack sufficient statistical evidence, we glimpse a possible leverage effect of purchase intensity on the relation between the interest aroused by interactive content and the perception of utilitarian value. Something similar, but in the opposite direction, occurs with the direct effect of interaction posts on engagement. Once again, even though the difference between the intensity groups is not statistically significant, it does appear that said effect is greater amongst members of the LI group (b=0.600, p<0.001) than amongst members of the HI group (b=0.382, p<0.001), allowing us to venture the possibility of a dampening effect of purchase intensity on the capacity of interaction posts to directly encourage participation in brand page activities.

In light of the results to emerge from this exploratory analysis and exercising due caution, we conjecture a possible two-fold moderating effect of brand purchase intensity on the role played by interaction posts: (1) a positive moderating effect concerning the influence these posts have on the perception of utility and (2) a negative moderating effect on their direct influence on engagement. Both effects may be seen as small signs in favour of H2.

DiscussionIn the new context of relationship marketing, social networks are an extremely valuable tool for firms when it comes to handling their relations with clients and when creating and maintaining real communities around their brands. Specifically, beyond merely serving as a window to promote products and brands, FBPs may contribute positively to business performance provided that relationship with clients can be enhanced and that customer engagement in communication and value creation through social interaction can be furthered. In this context, firms clearly need to decide what their communication strategy will be if they are to secure the relational engagement of page users. Based on this, in the present study we posit that more active commitment may be obtained from users by offering them an interactive experience in the brand page, particularly an experience which proves sufficiently appealing and valuable.

As contended by authors such as Brodie et al. (2011), Gummerus et al. (2012) or Malthouse and Calder (2011), customer engagement is attained through relational customer experiences. The findings to emerge from the empirical analysis evidence that experiences with the brand page and the experiential values obtained determine users’ level of engagement, allowing us to consider an experiential route of engagement. At the same time, it seems clear that active engagement can be understood as a reciprocating behaviour. In order to explain this general remark more clearly, two important clarifications should be made.

Firstly, it should also be recognized that, contrary to what was conjectured, the experiential route is not the main way of promoting engagement. Whilst not denying the relative importance of the experiential route, engagement does appear to be an immediate response to the direct call to participate made by the firm to page users through so-called interaction posts.

Secondly, we see how the explanatory capacity of experiential value is due exclusively to utility value, which means that the utilitarian experiential route of engagement fully prevails over the hedonic experiential route. The informational support received when making purchase decisions generates a feeling of reciprocity which can only be matched by reciprocation, a behaviour which is slightly more evident in the case of page users who display greater brand purchase intensity. Contrary to expectations, the particular case analyzed does not seem to indicate that entertainment value motivates engagement. It may thus be concluded that perceived utility encourages active participation, whereas entertainment produces receptive users but not active participants. One feasible explanation for this result could be related to the content of the posts analyzed. Civijikj and Michahelles’ (2013) findings reveal that brand posts which contain entertaining content trigger the highest level of active engagement (i.e., liking, commenting and sharing behaviours), followed by posts providing brand-related information and posts which offer remuneration. However, the FBP analyzed in our study does not contain specific “entertainment posts”, even if users can find entertainment in other posts. Thus, the firm is responsible for perceived utilitarian value (informational BP), but is not responsible for perceived hedonic value. Therefore, users would reciprocate a firm's efforts with active participation but would only reciprocate informative efforts.

Another possible explanation for this result concerns individuals’ motivations to use the FBP, which might help to ascertain whether engagement is determined by the perception of utility or the perception of entertainment. Unfortunately, the study of the relationship between users’ motivations and participation has yielded contradictory evidence. Pöyry, Parvinen and Malmivaara's (2013) analysis reveals that hedonic motivations for using the company-hosted Facebook brand page relate to a higher propensity to participate in the community, whereas utilitarian motivations relate more strongly to merely browsing the community page. Other studies, however, point to participation linked to utilitarian-motivated individuals. For instance, Zaglia (2013, p. 219) affirms that, compared to Facebook groups, “in [company-hosted Facebook] fan pages, activities related to the community's purpose are [more] central, and consumers participate mainly due to utilitarian (e.g., getting information) motives”. In this line, Shao and Ross (2015) explore different stages of consumer interaction with a FBP community and conclude that community users require entertainment if their involvement with the FBP is to be sustained. However, as consumers become more sophisticated, “information seeking is the only significant motive for an individual to post on a Facebook brand page” (p. 253). In our study, we do not measure user motivation although we do find that FBP users perceive both utility and entertainment (the mean values of the indicators are over 3). Therefore, in a Facebook fashion-brand page, both utilitarian and hedonic experiential values may prove to be key elements vis-à-vis retaining individuals in the Facebook community. However, in terms of engagement, users seem to be motivated by utilitarian reasons, since only the utilitarian experiential value determines active participation in FBP activities.

As regards how efficient BPs are as (either direct or indirect) determinants of engagement, our findings point to a different effect of each type of post depending on the kind of content in question: an indirect effect of information posts (through utility), a direct effect of interaction posts, and no effect of image posts.

Irrespective of user brand purchase intensity, information posts positively and significantly impact on perceived utility and entertainment, although their indirect effect on engagement is only evident through the utilitarian route. One may, therefore, sense a certain wish to respond to the call of duty sparked by the perceived utility of brand-related information which aids problem solving and/or decision making. Nevertheless, the fact that this indirect effect on engagement is not as strong as anticipated might be due to the existence of users who are mere information seekers and act as lurkers, in other words, who browse without reciprocating (Chan and Li, 2010; de Valck et al., 2009).

Unlike the above, image posts in no way affect engagement. Through these posts, the brand “shows off” its social relevance to its fans by appearing in various media. However, this sparks no feeling of reciprocity amongst fans, perhaps because such content is seen as a form of advertising. Even so, image posts do make quite a relevant contribution to utility, albeit only in the case of users who display less brand purchase intensity. When taking or boosting their purchase decisions, these less intense purchasers need to know that the brand has a social presence and is recognized in the market. For such buyers, the fact that the brand appears on TV or radio programs and that famous people wear its clothes proves useful when it comes to evaluation and choice in the purchase decision process. For regular purchasers of the brand, namely those who are probably more familiar it and have a more clearly defined image thereof, such posts are not so useful. What does prove surprising is that image posts fail to contribute to the perception of hedonic experiential value. The possibility should therefore be considered that image posts are not comparable to “entertainment posts”, messages designed for users to enjoy, entertain and amuse themselves with content that is not specifically related to the brand (Cvijikj and Michahelles, 2013; Luarn et al., 2015).

Finally, interaction posts contribute towards the perception of utility (albeit to a greater extent in the case of the higher purchase-intensity group) and entertainment (very clearly in the two groups), without this effect becoming noticeable, through either of the two experiential routes, in behavioural engagement. In particular, the effect of interaction posts on utilitarian experiential value merits a brief explanation, since it might be surprising that posts which provide no kind of information make a significant contribution to perceived utility. In our view, for a specific user, BPs which encourage participation are not useful in themselves, but do prove valuable in that they foster the production of content generated by other users (such as comments, opinions or answers to questions), which might be helpful in decision making. Thus, the greater the amount of information available on a brand page thanks to these user posts, the greater the perceived utility of the page. Through this indirect route, interaction posts contribute to users’ utilitarian experiential value.

What would appear to be more evident is the particularly strong direct effect of interaction posts on engagement, a phenomenon found in both groups of users. As a result, what is interesting in this case is not so much its explanation, which is obvious given the nature and purpose of this type of BP, but how it is interpreted. In this vein, we find two possible interpretations which correspond, respectively, to a pessimistic and an optimistic view of relational reality in brand pages. On the one hand, corresponding to the more pessimistic view, users in general (but more clearly less intense purchasers) might be felt to respond directly to interaction posts since they promise more or less definite rewards (e.g., the right to take part in a draw) in exchange for active participation. As can be seen in Table 1, BPs which generate more attention and prove more interesting are precisely those which provide information about special offers (a kind of information post with an average interest score of 4.25 out of 5) and those which announce prize draws amongst fans (a kind of interaction post displaying an average score of 4.15). Moreover, the very fact that subjects in the sample answered the questionnaire serves to support such an interpretation, since it should be remembered that the survey was put up in an interactive post that rewarded user cooperation by offering them a voucher.

In contrast to this pessimistic view, one might be inclined to think that the less relevant role of the experiential route (favouring the direct effect of interaction posts) is not necessarily indicative of a low level of commitment to the brand page. Perhaps, users who receive experiential values reciprocate with “brand engagement” (e.g., positive word-of-mouth in their most personal environment, brand advocacy, brand acceptance, brand loyalty, inhibition to switch brand, propensity to stay in the brand relationship and other consumer brand-supporting behaviours) outside the brand page, but not in the public forum of the virtual community. The fact that they do not correspond to the value received with their active participation in the page activities might be due to the inhibiting effect of certain personality traits, such as having a more withdrawn or introverted character (e.g., Kabadayi and Price, 2014), aversion to publicly expressing their opinions or drawing attention, a fear of being labelled as show-offs, concern that their opinions and comments might go unnoticed or unappreciated, or lack of faith in their ability to make contributions that prove original and interesting to others. In such instances, interaction posts provide the opportunity and the means of expression these users were seeking to participate unselfishly in the FBP and to repay the benefits received. Unfortunately, the information available does not allow us to gauge to what extent which of the two views (or indeed a combination of the two) is the dominant one.

In summary, by way of a general conclusion, an overall analysis of the results obtained in our research allows us to state that the three kinds of BPs considered prove effective in terms of their contribution to the brand page's relationship success, although not all of them contribute in the same way and with the same intensity. To a greater or lesser degree and not always for the two groups of users, the three kinds of BPs contribute significantly to producing experiential values, but only information and interaction posts ultimately affect engagement. Image posts do not in any way promote engagement, even if they generate utility for users with lower brand purchase intensity. Exclusively through the utilitarian experiential route, information posts encourage user behavioural engagement, regardless of the user type. Aside from any experiential route and through a more direct route, interaction posts are the main determinant of engagement behaviour, especially in the case of users with lower brand purchase intensity.

Managerial implicationsThe findings of our research provide firms which invest in Facebook-page brand communities with some guidelines to foster user brand-page engagement and so succeed in their SNS-based relationship marketing strategy.

The first implication is that information and image posts are not as efficient as interaction posts in terms of their ability to encourage active participation in a Facebook brand page. Yet this should not lead a community manager to a feeling of frustration, as it is possible to make a positive comment on the relational efficacy of information and image posts. If page-user interaction with such posts helps generate experiential value, the firm can feel well pleased. In our view, generating utilitarian and/or hedonic values might prove to be a relational result in itself, regardless of whether it is subsequently manifested in engagement behaviour on the page. Although we have not explored the matter in the present analysis, we feel that the experiential values to emerge from users’ elaboration process of BPs and from their interaction with the brand page might translate directly to more positive attitudes towards the brand (Chen et al., 2015) and indirectly to various brand-supportive behaviours such as advocacy and loyalty. In any case, the firm might not need to seek immediate reward for having set up a FBP or virtual brand community. It should at least, however, consider that (1) users access the page and actually read the posts, indicating that they are in fact fans of the brand, and (2) users have relational experiences and obtain experiential values, which will strengthen their position as fans and help to enhance the brand's social image. This does not mean that the firm should cease in its attempt to create a veritable community feeling so that active participation is more spontaneous and information flows more fluently.

A second implication of this research is the enormous potential of interaction posts to provide the two types of experiential values and, directly, to engage users in the FBP. We have interpreted this result as an opportunistic conduct. According to this initial interpretation, behavioural engagement in the brand page might, first and foremost, be opportunistic behaviour spurred by the desire to be given a more or less certain and immediate reward. Nevertheless, even if engagement is self-interested, what is true is that active user participation breathes life into the virtual brand community. The complementary interpretation is that interaction posts act as a mechanism to prevent the reluctance to participate and self-disclose that some people experience. In this way, the hurdles preventing natural and spontaneous participation can be overcome by users being specifically invited (through interaction posts) to engage in some concrete activity by the firm (e.g., voting, commenting or uploading photos).

A third implication is related to customer relationship management through FBP. A firm should be aware of the segments of customers who follow it on its Facebook brand page and the type of posts preferred by each segment so as to then be able to offer content adapted to the different categories of followers. Even if our findings are contextualized in the case of a specific fashion brand, we have pointed to some attitudinal and behavioural differences between page users depending on their brand purchase intensity. Although all types of page users built their utilitarian and hedonic experiences with the FBP through information posts, they differ in terms of the experiential value extracted from both image and interaction posts. Thus, image posts might prove more appropriate for lower-intensity buyers who are looking for quick-fire information about the brand. Contrastingly, interaction posts prove to be more experientially effective when targeting users displaying a closer relationship with the brand (higher-intensity buyers).

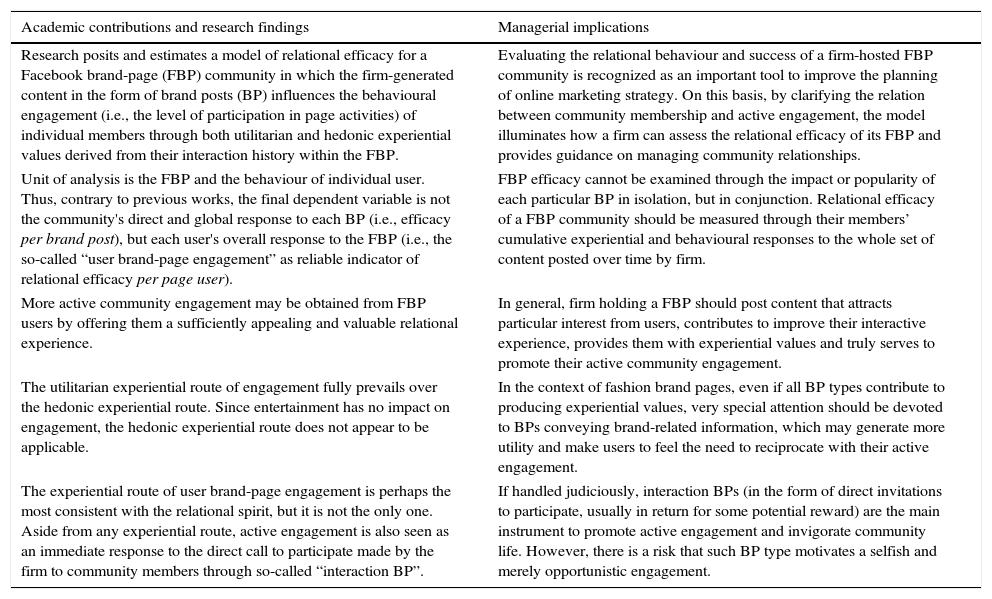

Table 8 offers a summary of the most relevant research contributions for academics and practitioners.

Synthesis of contributions for academics and practitioners.

| Academic contributions and research findings | Managerial implications |

|---|---|

| Research posits and estimates a model of relational efficacy for a Facebook brand-page (FBP) community in which the firm-generated content in the form of brand posts (BP) influences the behavioural engagement (i.e., the level of participation in page activities) of individual members through both utilitarian and hedonic experiential values derived from their interaction history within the FBP. | Evaluating the relational behaviour and success of a firm-hosted FBP community is recognized as an important tool to improve the planning of online marketing strategy. On this basis, by clarifying the relation between community membership and active engagement, the model illuminates how a firm can assess the relational efficacy of its FBP and provides guidance on managing community relationships. |

| Unit of analysis is the FBP and the behaviour of individual user. Thus, contrary to previous works, the final dependent variable is not the community's direct and global response to each BP (i.e., efficacy per brand post), but each user's overall response to the FBP (i.e., the so-called “user brand-page engagement” as reliable indicator of relational efficacy per page user). | FBP efficacy cannot be examined through the impact or popularity of each particular BP in isolation, but in conjunction. Relational efficacy of a FBP community should be measured through their members’ cumulative experiential and behavioural responses to the whole set of content posted over time by firm. |

| More active community engagement may be obtained from FBP users by offering them a sufficiently appealing and valuable relational experience. | In general, firm holding a FBP should post content that attracts particular interest from users, contributes to improve their interactive experience, provides them with experiential values and truly serves to promote their active community engagement. |

| The utilitarian experiential route of engagement fully prevails over the hedonic experiential route. Since entertainment has no impact on engagement, the hedonic experiential route does not appear to be applicable. | In the context of fashion brand pages, even if all BP types contribute to producing experiential values, very special attention should be devoted to BPs conveying brand-related information, which may generate more utility and make users to feel the need to reciprocate with their active engagement. |

| The experiential route of user brand-page engagement is perhaps the most consistent with the relational spirit, but it is not the only one. Aside from any experiential route, active engagement is also seen as an immediate response to the direct call to participate made by the firm to community members through so-called “interaction BP”. | If handled judiciously, interaction BPs (in the form of direct invitations to participate, usually in return for some potential reward) are the main instrument to promote active engagement and invigorate community life. However, there is a risk that such BP type motivates a selfish and merely opportunistic engagement. |

To conclude the work, its most salient limitations as well as the possibilities it opens up for future research should be mentioned. Firstly, the study has been carried out using data gathered from a single FBP representing the fashion industry, which reduces the need to control the effect of certain brand- or page-specific variables, but limits generalizability. Validation of our results and conclusions requires the model be tested on other FBPs within and outside the sector in question (Pöyry et al., 2013). Secondly, experiential values originate from the overall set of relational interactions involving users in the brand page, not only with BPs. Future inquiry should, therefore, posit a more inclusive model in which brand posts and user posts can compete freely and contemporaneously against each other to test their respective abilities to generate experiential value and motivate engagement. Thirdly, there is a need to recognize that much of the variability in engagement is not accounted for by brand posts and experiential values, leading us to consider that variables which are not related to users’ interaction with the FBP might lie at the heart of their decision to make an active engagement. The model might be furthered by including subjects’ general personality traits which we have used to explain and interpret the results. Certain personal traits such as sociability, the sense of social involvement, attitude towards collaboration with others, aversion to opportunism, extraversion, showing off, self-esteem or perceived creativity might well help to better explain engagement. Likewise, it might be worth including user variables that are more directly linked to the brand page (e.g., motivations to use the FBP and a sense of belonging to the community), to the brand (e.g., brand love), the product (e.g., knowledge and expertise, or attitude to fashion) or the setting (e.g., motivations and attitudes towards the Internet or social networks). Following on from de Valck et al. (2009), Kabadayi and Price (2014), van Doorn et al. (2010), Wasko and Faraj (2005) or Wiertz and de Ruyter (2007), individual user traits can directly or indirectly affect the likelihood and level of user engagement or moderate the relations posited in the model. Fourthly, a model which is more understanding of the reality should consider other expressions of user engagement aside from brand page (e.g., brand advocacy or brand loyalty) as indicators of the success of online relational strategy. Finally, further to our investigation, even if this means changing the approach adopted here, it would be desirable to examine in detail, by positing specific hypotheses and applying the right methodology (e.g., experiments), how diverse features of a brand post (brand- or product-related versus non-related content, informative versus emotional orientation, formal versus informal language, serious versus amusing format, etc.) impact on user response to the BP (quantified as the number of likes, shares and comments on this BP).

The authors are grateful for the financial support received from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (research project ECO2012-36275).