Teacher Talent Management (TTM) is an organizational paradigm designed to ensure the timely recruitment of the most talented teachers in educational settings. It employs a multidimensional process encompassing attraction, selection and culture, development and succession, retention and climate, evaluation, and knowledge management, demonstrating positive impacts on student outcomes and teacher performance, among other benefits. This study represents the first empirical effort to measure TTM in Spain using a psychometrically validated tool. Data were collected through non-probabilistic sampling from 302 schools across Spain. By employing a cluster analysis approach, the study identifies distinct patterns of TTM implementation among schools. The findings reveal two clusters: high- and low-TTM schools, highlighting strengths in certain areas while uncovering significant room for improvement in teacher development and succession planning. Innovation and research emerged as key differentiating variables between schools with lower and higher TTM levels. The study highlights several implications, including the need for paradigm shifts in development plans, the introduction of mentoring programs, enhanced university training for future teachers, and policy initiatives to promote a talent-oriented culture in schools.

La Gestión del Talento Docente (GTD) es un paradigma organizativo diseñado para garantizar la contratación oportuna del profesorado con más talento en los centros educativos. Emplea un proceso multidimensional que abarca la atracción, la selección-cultura, el desarrollo-sucesión, la retención-clima, la evaluación y la gestión del conocimiento y demuestra impactos positivos en los resultados académicos de los estudiantes y en el rendimiento docente, entre otros beneficios. Este estudio representa el primer esfuerzo empírico para medir la GTD en España y utiliza el test TTMAT validado psicométricamente. Los datos se recogen a través de un muestreo no probabilístico de 288 centros educativos de toda España. Mediante el empleo de un análisis de clusters, el estudio identifica distintos patrones de aplicación de la GTD en los centros escolares. Los resultados revelan la existencia de dos grupos: centros con un alto y un bajo nivel de GTD y destaca los puntos fuertes en determinadas áreas, al tiempo que descubre un importante margen de mejora en el desarrollo del profesorado y la planificación de la sucesión. La innovación y la investigación aparecen como variables diferenciadoras clave entre los centros con niveles más bajos y altos de GTD. El estudio pone de relieve varias implicaciones, como la necesidad de cambios de paradigma en los planes de desarrollo, la introducción de programas de tutoría, la mejora de la formación universitaria del futuro profesorado y las iniciativas políticas para promover una cultura orientada al talento en las instituciones educativas.

Talent has become a Human Resources (HR) philosophy in many organizations around the world since the 90s due to the McKinsey & Company report that better talent is worth fighting (Chambers et al., 1998), which was the trigger through the war for talent. Talent management aims get the right person in the right job at the right time (Beechler & Woodward, 2009) which currently undergoes a transformation through the application of generative AI tools to predict talent trends (Bennett & Martin, 2025; Evans et al., 2025).

This organizational management paradigm, focused on the best and the brightest (the talents), also can be applied to the education field. In education, the focus is on the student’s achievement. However, behind this goal, educational systems around the world are struggling with aspects related to TTM, such as teacher’s shortage, retention, attraction to teaching profession, professionalized training, professional career, motivation, commitment and the enhancement of the teaching profession prestige (Clemson et al., 2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2005).This should lead us to reflect that the spotlight should not be just the students, but the teachers and their Institutional leadership too within the TTM paradigm.

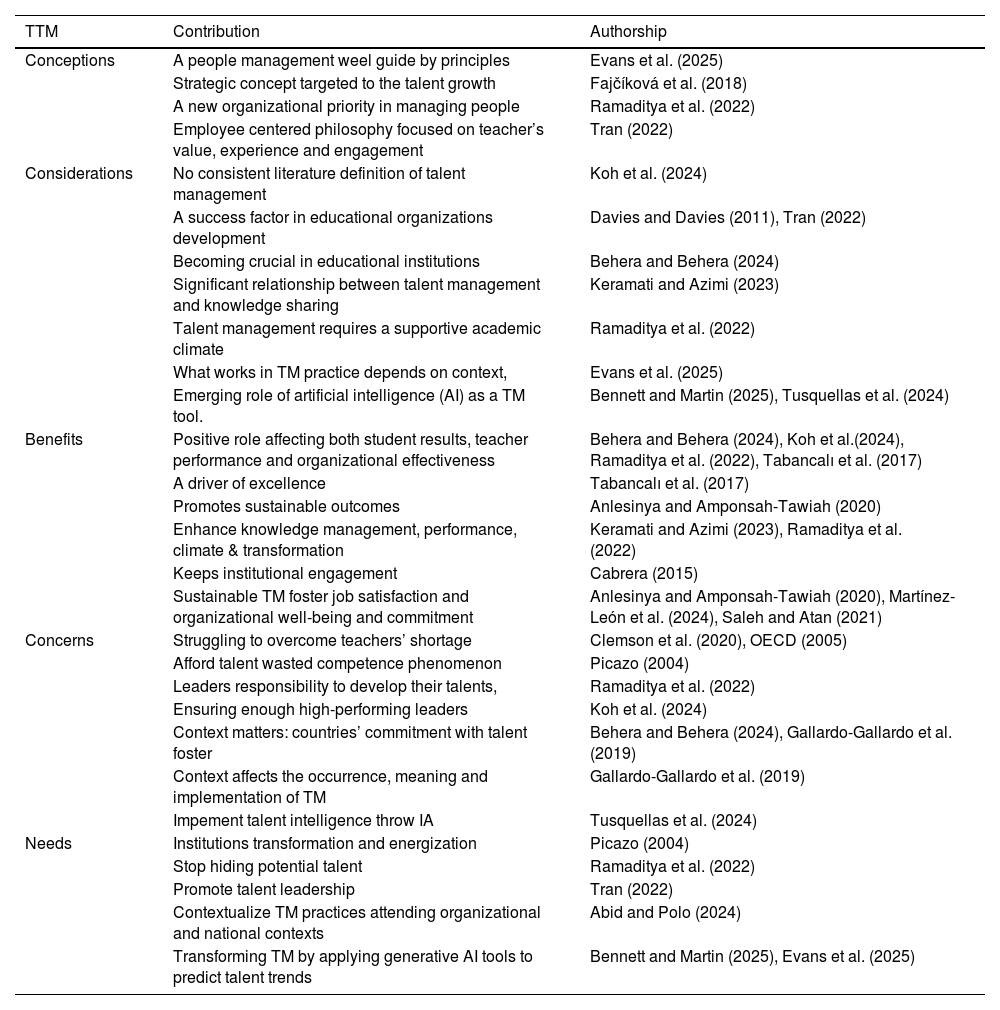

The literature within the framework of this paradigm provides a large conception, considerations and highlights benefits, concerns and needs, which are presented in Chart 1. TTM focuses on the teacher’s potential, their improvement, experience and engagement. conceptions remarking an employee centered philosophy. It represents a strategic concept targeted to the talent growth and the attractive and suitable development. It seems to become a crucial factor in schools. We can remark that it is considered a successful factor in educational organizations because it provides positive benefits in student results, teacher performance and organizational effectiveness. So that it is a driver of excellence and promotes sustainable outcomes.

Conceptions, considerations, benefits, concerns and needs related to the TTM paradigm

| TTM | Contribution | Authorship |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptions | A people management weel guide by principles | Evans et al. (2025) |

| Strategic concept targeted to the talent growth | Fajčíková et al. (2018) | |

| A new organizational priority in managing people | Ramaditya et al. (2022) | |

| Employee centered philosophy focused on teacher’s value, experience and engagement | Tran (2022) | |

| Considerations | No consistent literature definition of talent management | Koh et al. (2024) |

| A success factor in educational organizations development | Davies and Davies (2011), Tran (2022) | |

| Becoming crucial in educational institutions | Behera and Behera (2024) | |

| Significant relationship between talent management and knowledge sharing | Keramati and Azimi (2023) | |

| Talent management requires a supportive academic climate | Ramaditya et al. (2022) | |

| What works in TM practice depends on context, | Evans et al. (2025) | |

| Emerging role of artificial intelligence (AI) as a TM tool. | Bennett and Martin (2025), Tusquellas et al. (2024) | |

| Benefits | Positive role affecting both student results, teacher performance and organizational effectiveness | Behera and Behera (2024), Koh et al.(2024), Ramaditya et al. (2022), Tabancalı et al. (2017) |

| A driver of excellence | Tabancalı et al. (2017) | |

| Promotes sustainable outcomes | Anlesinya and Amponsah-Tawiah (2020) | |

| Enhance knowledge management, performance, climate & transformation | Keramati and Azimi (2023), Ramaditya et al. (2022) | |

| Keeps institutional engagement | Cabrera (2015) | |

| Sustainable TM foster job satisfaction and organizational well-being and commitment | Anlesinya and Amponsah-Tawiah (2020), Martínez-León et al. (2024), Saleh and Atan (2021) | |

| Concerns | Struggling to overcome teachers’ shortage | Clemson et al. (2020), OECD (2005) |

| Afford talent wasted competence phenomenon | Picazo (2004) | |

| Leaders responsibility to develop their talents, | Ramaditya et al. (2022) | |

| Ensuring enough high-performing leaders | Koh et al. (2024) | |

| Context matters: countries’ commitment with talent foster | Behera and Behera (2024), Gallardo-Gallardo et al. (2019) | |

| Context affects the occurrence, meaning and implementation of TM | Gallardo-Gallardo et al. (2019) | |

| Impement talent intelligence throw IA | Tusquellas et al. (2024) | |

| Needs | Institutions transformation and energization | Picazo (2004) |

| Stop hiding potential talent | Ramaditya et al. (2022) | |

| Promote talent leadership | Tran (2022) | |

| Contextualize TM practices attending organizational and national contexts | Abid and Polo (2024) | |

| Transforming TM by applying generative AI tools to predict talent trends | Bennett and Martin (2025), Evans et al. (2025) |

Among its benefits, sustainable TTM contributes to achieve job satisfaction, organizational well-being and commitment because helps teachers consider themselves as elements of the school’s organizational culture. So enhance climate, keeps institutional engagement, teacher’s performance and school transformation. In addition, TTM foster knowledge sharing what contribute to school’s knowledge capital increase. Chart 1 also shows crucial concerns in TTM such as whether it is an inclusive or exclusive philosophy (to all the teachers or just someone). A main issue is to afford talent wasted competence phenomenon which concerns leaders’ responsibility to develop their talents, and their lack of knowledge or experience. Because although the intrinsic appeal of teaching can be a reason for choosing this profession, its capacity to generate job satisfaction and teacher enchantment among serving teachers is conditioned by perceptions of teaching performance, affective organizational commitment, cultural values and internal processes at schools. So that how to lead TTM by envisioning it as a catalyst for leaders committed to TTM, ensuring enough high-performing leaders is a huge concern.

Educational research in this field echoes the need that schools must transform and energize themselves to offer their teachers a life plan and development path which discovers or fosters their potential and encourages them to change and transform. But the reality is that context matters because it affects TTM practices. And at this point, context matters at two stratums. At a macro level, where we find countries’ commitment with talent foster and TTM policies, and a micro level where the environmental aspects that teachers face in their institution are determinant (culture, climate, leadership). In both cases context is the catalyst to raising talent. Therefore, TTM practices need be contextualized by attending organizational and national contexts and framed in the recently generative AI tools. As it is said, TTM could be considered a humanistic approach because it focuses on teachers’ value and care, emphasizing their experience and potential for growth in an inclusive context. However, when we try to understand the theorical construct which supports this paradigm, literature shows no consistent definition.

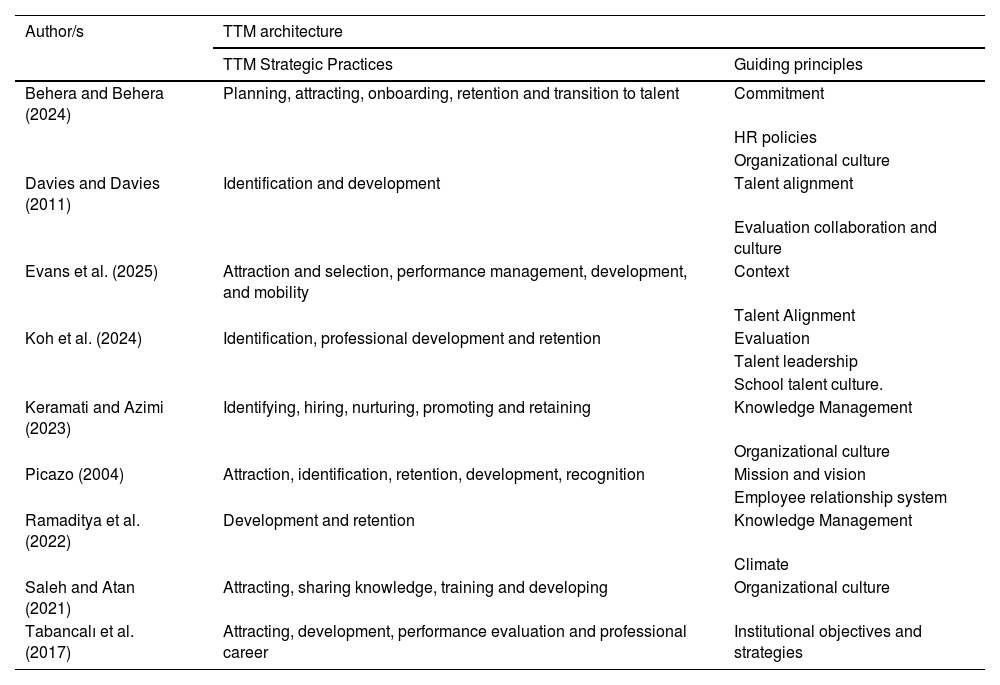

TTM is presumed to be a systematic management process; but literature does not show strong arrangement about this unity term, due to the lack of agreement and the spread of conceptions. Chart 2 shows the approaches to TTM architecture concept according to sources. It seems to be agreement about the fact that TTM is an integrative framework that includes strategic set-processes and key guidelines. However, there is little consensus on the number of processes that comprise it. Some authors understand it as a two-step process, while others see it as a six-step process. Most of the sources found agreement on a five-step process. The most frequently repeated processes, on which there seems to be greater consensus, are attraction, development, and retention. Most sources say that these process-set are accompanied by guiding principles but do not agree about which one. The most prominent factor is organizational culture, followed by commitment (which could be associated with talent alignment), climate, evaluation and talent leadership.

Approaches to TM architecture concept according to literature

| Author/s | TTM architecture | |

|---|---|---|

| TTM Strategic Practices | Guiding principles | |

| Behera and Behera (2024) | Planning, attracting, onboarding, retention and transition to talent | Commitment |

| HR policies | ||

| Organizational culture | ||

| Davies and Davies (2011) | Identification and development | Talent alignment |

| Evaluation collaboration and culture | ||

| Evans et al. (2025) | Attraction and selection, performance management, development, and mobility | Context |

| Talent Alignment | ||

| Koh et al. (2024) | Identification, professional development and retention | Evaluation |

| Talent leadership | ||

| School talent culture. | ||

| Keramati and Azimi (2023) | Identifying, hiring, nurturing, promoting and retaining | Knowledge Management |

| Organizational culture | ||

| Picazo (2004) | Attraction, identification, retention, development, recognition | Mission and vision |

| Employee relationship system | ||

| Ramaditya et al. (2022) | Development and retention | Knowledge Management |

| Climate | ||

| Saleh and Atan (2021) | Attracting, sharing knowledge, training and developing | Organizational culture |

| Tabancalı et al. (2017) | Attracting, development, performance evaluation and professional career | Institutional objectives and strategies |

Despite the growing body of research highlighting the strategic importance and potential benefits of TTM for educational organizations, such as improved student outcomes, teacher performance, and organizational effectiveness (Clemson et al., 2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2005), the literature also reveals significant limitations and unresolved issues. There is a notable lack of consensus regarding the conceptual definition and operationalization of TTM, with studies proposing diverse frameworks and processes and little agreement on the guiding principles or key components involved (Beechler & Woodward, 2009; Liechti & Sesé, 2024). Much of the existing research is context-dependent, shaped by national policies, institutional cultures, and local leadership practices, which restricts the generalizability of findings (Bolívar, 2013; Gratacós et al., 2024). Methodologically, the field is constrained by the predominance of descriptive or conceptual approaches over empirical research, and by a scarcity of studies employing validated instruments in diverse educational settings (Liechti & Sesé, 2024). Furthermore, ongoing debates persist regarding the inclusivity versus exclusivity of TTM practices and the practical challenges of implementation, particularly in public education systems with restrictive regulations (Bolívar, 2017; Gairín & Castro, 2010). This study addresses these gaps by providing an empirically grounded assessment of TTM in Spanish schools, utilizing a validated instrument and robust statistical techniques to identify distinct school profiles and examine the influence of contextual and organizational factors. In doing so, it contributes to clarifying the conceptual framework of TTM and offers new evidence on its practical application within the Spanish educational context, where empirical research remains limited (Bolívar & Moreno, 2006; Martínez-León et al., 2024; Mérida-Lópeza et al., 2022).

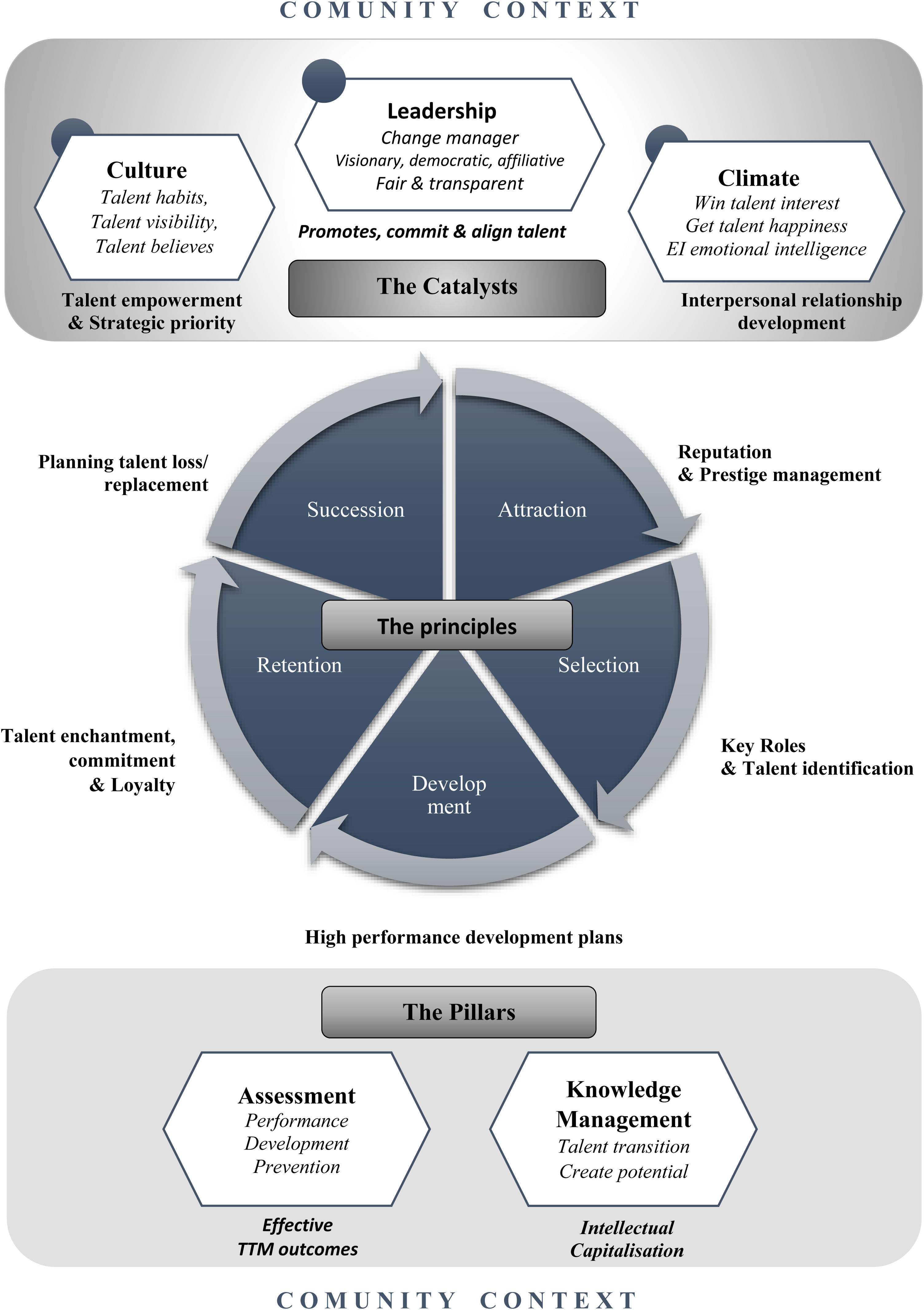

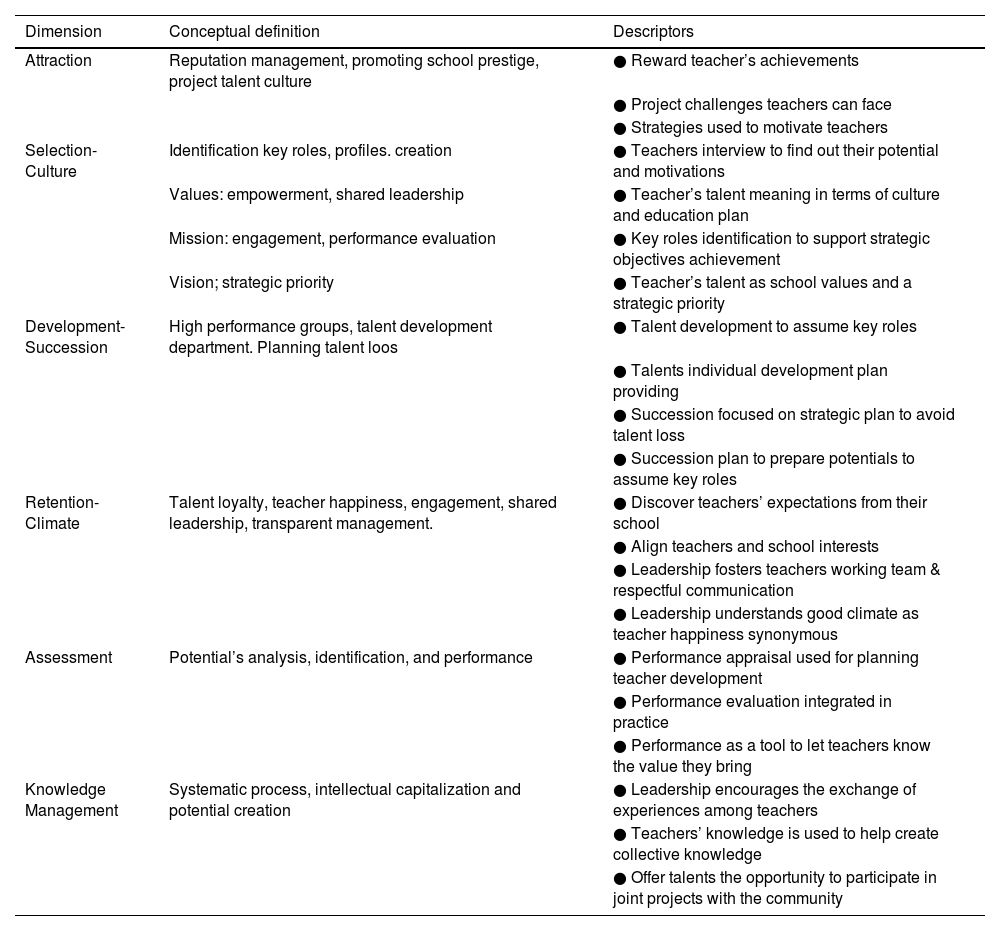

Based on these theorical contexts Figure 1 aims to capture the TTM paradigm arising from currently existing approaches, processes and contributions which echoes the research in this field. We agree with most of the sources found in the fact that this framework needs to be understood as an architecture. In our case, we understand it as a holistic approach to boost teachers’ potentials throw a systematic process implemented through attraction, selection, development, retention and succession. This process rests on two pillars: assessment and knowledge management. Finally, it has three catalytic elements: climate, culture and talent leadership.

According to this framework Liechti and Sesé (2024) operationalized TTM construct. Chart 3 shows these dimensions, conceptions and some of the descriptors. This operationalization covers almost all the factors found in the literature. It is interesting to see how, from the construct validation procedure, we get six dimensions, three of them regrouped. Although we do not have data that allows us to confirm why three of them are merged, maybe is due to subjects’ perceptions, with their responses, found similarities across the items.

TTM six-dimensions construct operationalization

| Dimension | Conceptual definition | Descriptors |

|---|---|---|

| Attraction | Reputation management, promoting school prestige, project talent culture | ● Reward teacher’s achievements |

| ● Project challenges teachers can face | ||

| ● Strategies used to motivate teachers | ||

| Selection-Culture | Identification key roles, profiles. creation | ● Teachers interview to find out their potential and motivations |

| Values: empowerment, shared leadership | ● Teacher’s talent meaning in terms of culture and education plan | |

| Mission: engagement, performance evaluation | ● Key roles identification to support strategic objectives achievement | |

| Vision; strategic priority | ● Teacher’s talent as school values and a strategic priority | |

| Development-Succession | High performance groups, talent development department. Planning talent loos | ● Talent development to assume key roles |

| ● Talents individual development plan providing | ||

| ● Succession focused on strategic plan to avoid talent loss | ||

| ● Succession plan to prepare potentials to assume key roles | ||

| Retention-Climate | Talent loyalty, teacher happiness, engagement, shared leadership, transparent management. | ● Discover teachers’ expectations from their school |

| ● Align teachers and school interests | ||

| ● Leadership fosters teachers working team & respectful communication | ||

| ● Leadership understands good climate as teacher happiness synonymous | ||

| Assessment | Potential’s analysis, identification, and performance | ● Performance appraisal used for planning teacher development |

| ● Performance evaluation integrated in practice | ||

| ● Performance as a tool to let teachers know the value they bring | ||

| Knowledge Management | Systematic process, intellectual capitalization and potential creation | ● Leadership encourages the exchange of experiences among teachers |

| ● Teachers’ knowledge is used to help create collective knowledge | ||

| ● Offer talents the opportunity to participate in joint projects with the community |

From this operationalization a school focused on TTM would be one that demonstrates to the community how teacher excellence is addressed, reflects on the meaning of excellence based on the school’s educational project, and creates talent profiles. It focuses on high-performing groups strategy providing individual development plans. Works to commit talent and designs and deploys a recognition/incentive system in collaboration with the community. Practices a talent culture which focuses on teacher’s excellence as a strategic priority. They practice evaluation to identify potential, performance, analysis, and engagement activity that allows talent to be aware of the value they bring. They systematize accessibility, sharing and application knowledge processes as a strategic resource to materialize talent transition, create potential and intellectually capitalize the organization.

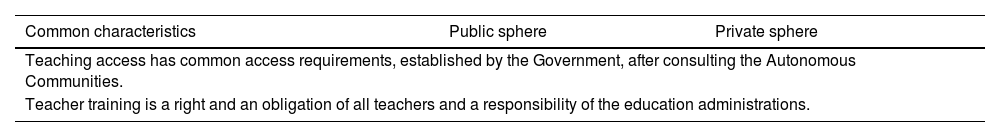

The current systems of access to public employment reflect a significant variety and impact on the possibilities and limitations linked to TTM (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2005). While in some countries, recruitment models are open and driven by the schools themselves, in others they are more restrictive and access is by public tender (Gratacós et al., 2024). When we try to figure out how HR policies related to TTM are applied in Spain we need to contextualize them in the Spanish education system. Chart 4 shows the considerations linked to the Spanish context in both the public and private schools.

Spanish education system characteristics in the public and private sphere in the framework of the TTM and reform proposals

| Common characteristics | Public sphere | Private sphere |

|---|---|---|

| Teaching access has common access requirements, established by the Government, after consulting the Autonomous Communities. | ||

| Teacher training is a right and an obligation of all teachers and a responsibility of the education administrations. | ||

| Differential characteristics | Public sphere | Private sphere |

|---|---|---|

| Selection | Procedure regulated normatively in three phases: opposition, competition and Traineeship | No normatively regulated procedure. Free selection based on CV and interview. |

| Development | Decentralized regulated general training plans for teaching staff. | Own in-service training plans without normative regulation. |

| Evaluation | Initial evaluation attached to the selection process. No teaching performance assessment regulation. | Teacher performance assessment established by the school, without normative regulation. |

| Retention | No existence of incentive systems linked to the public system. | Own incentive systems |

| Reform proposals in the public sphere | Consideration | Needs |

|---|---|---|

| Selection | Current model access inadequate or very inadequate. | Model access review to orient selection towards a modern system to get the best teachers (based on their competences, knowledge, skills and attitudes). |

| It has not changed in the last 40 years. | ||

| Development | Teacher training should be considered as a merit for promotion and professional development both horizontally and vertically. | Integrate teacher training into the professional teaching career. |

| Professional career | Effects of its regulation: six-year periods, access to other teaching staff competitions, inspectors staff access, posts abroad competitions, technical teaching advisors in the administration competitions. | Appropriate professional career establishment. |

| Support teachers in their professional careers. | ||

| Evaluation | Teacher’s professional development must have evaluation instruments to measure teaching function linked to the professional competence’s framework. | Promote performance evaluation procedures for the teaching profession. |

| Recognition | Administration support and commitment of the best performance of professional teaching competences. | Recognise good teaching development linked to complementary salaries. |

From Chart 4 we can presume that the center ownership affects TTM practices. While private schools have greater freedom to select their teaching staff, develop and promote incentives according to their priorities, public schools have their own regulations that restrict the possibility of integrating TTM practices such teachers’ selection and recognition systems. Even if Spain has experienced a development in education, school management is actively linked to the different political circumstances in recent decades. This investment seems not been translated, in any significant way, into improved learning and seems that school management has a serious responsibility on it (Bolívar, 2013). School management models follow successively, but they do not provide the answer to how to improve the selection processes (Gratacós et al., 2024), what comprehensive actions need to be taken to strengthen professional development (Matarranz, 2022; Rupérez, 2021), how to shape a new teaching profession model (Zabalza, 2022) and which management trend is required (Rodríguez et al., 2013). In addition, a critical factor in Spain is attached to school management about what school does or can do to improve the teaching work and student results (Bolívar & Moreno, 2006). There is a constant aspiration among educators to participate more effectively in the main areas of TTM, including selecting, training, and promoting teachers (Gairín & Castro, 2010). However, school headmasters in Spain perceive a limited capacity for action regarding the teachers they oversee (Bolívar, 2017). A final important issue in the Spanish TTM context concerns in how to enhance teacher satisfaction. throw school climate, cultural values, training, leadership and teacher participation in decision-making (Martínez-León et al., 2024; Mérida-Lópeza et al., 2022).

The Spanish educational system is currently undertaking reforms that prioritize professional development, evaluation, promotion, and incentives for teachers (Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2022). As shown in Chart 4, it is particularly important in the Spanish context to improve teacher recruitment and selection processes to better align with the professional competence’s framework. Additionally, there is an emphasis on enhancing teacher performance assessment to recognize teachers’ work and achievements, as well as on developing a professional career model that reflects the unique characteristics of the teaching profession. In this context, a central research question arises: To what extent do Spanish schools manage teacher talent? The primary objective of this study is to assess Teacher Talent Management (TTM) in Spanish schools, providing a detailed account of its implementation and an overview of the current TTM landscape. Using cluster analysis, the study aims to identify distinct patterns of TTM across schools. A secondary objective is to examine how factors such as age, gender, type of school, size, ownership, and innovation are associated with differential TTM profiles.

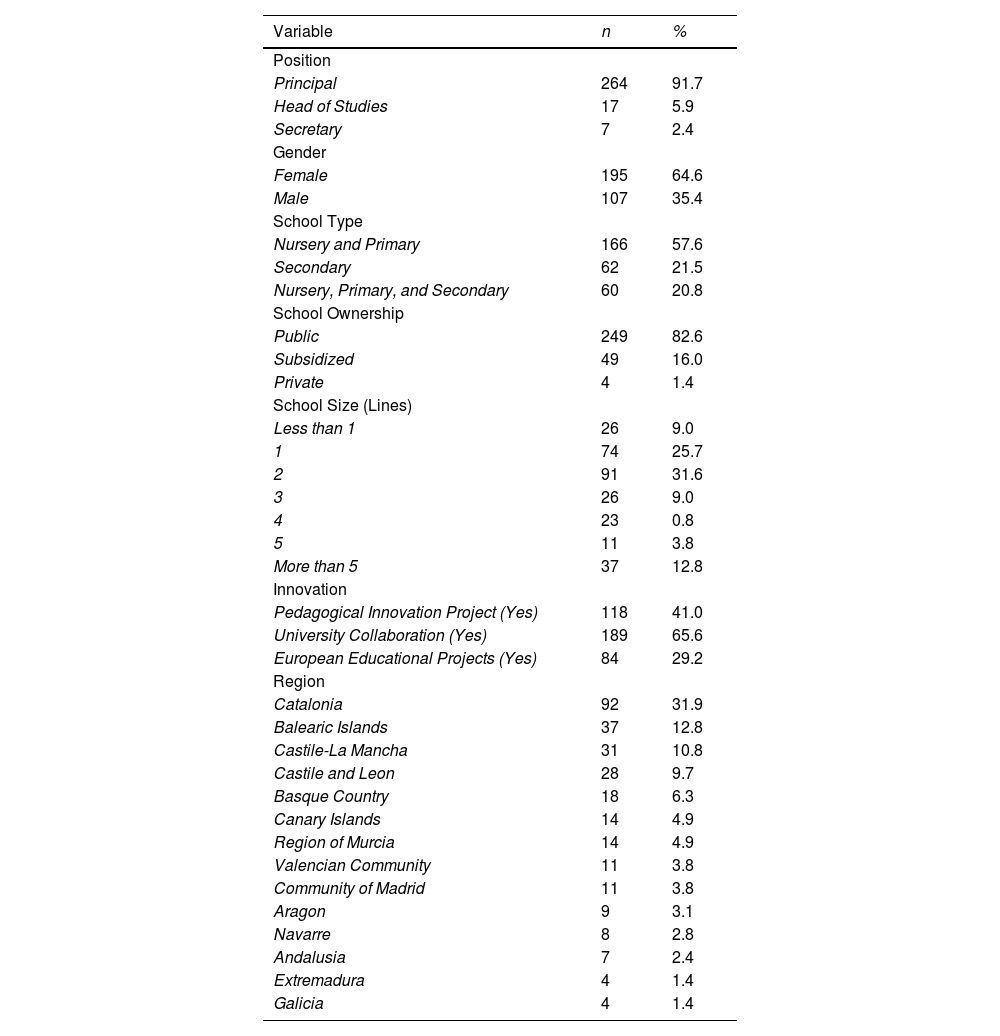

MethodParticipantsA mixed random and online incidental sampling strategy was employed. A random sample of 900 educational centers was initially drawn from the comprehensive list of all Spanish schools (around 20,000) and contacted via email. Of these, 302 centers completed the questionnaire, yielding a 34% response rate. The data matrix was subjected to outlier detection and elimination, removing 5% of the most extreme multidimensional outliers. This process resulted in a final sample of 288 participants, primarily principals (91.7%), with a gender distribution of 64.6% female and 35.4% male. Most participants are from nursery and primary schools (57.6%), with the majority being public institutions (82.6%). The sample includes a commitment to innovation, with 41% of schools involved in pedagogical projects and 65.6% collaborating with universities. Geographically, the sample is diverse, with significant representation from Catalonia (31.9%) and other regions across Spain. Table 1 provides the complete descriptive statistics for these variables.

Sample descriptives (n = 288)

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Position | ||

| Principal | 264 | 91.7 |

| Head of Studies | 17 | 5.9 |

| Secretary | 7 | 2.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 195 | 64.6 |

| Male | 107 | 35.4 |

| School Type | ||

| Nursery and Primary | 166 | 57.6 |

| Secondary | 62 | 21.5 |

| Nursery, Primary, and Secondary | 60 | 20.8 |

| School Ownership | ||

| Public | 249 | 82.6 |

| Subsidized | 49 | 16.0 |

| Private | 4 | 1.4 |

| School Size (Lines) | ||

| Less than 1 | 26 | 9.0 |

| 1 | 74 | 25.7 |

| 2 | 91 | 31.6 |

| 3 | 26 | 9.0 |

| 4 | 23 | 0.8 |

| 5 | 11 | 3.8 |

| More than 5 | 37 | 12.8 |

| Innovation | ||

| Pedagogical Innovation Project (Yes) | 118 | 41.0 |

| University Collaboration (Yes) | 189 | 65.6 |

| European Educational Projects (Yes) | 84 | 29.2 |

| Region | ||

| Catalonia | 92 | 31.9 |

| Balearic Islands | 37 | 12.8 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 31 | 10.8 |

| Castile and Leon | 28 | 9.7 |

| Basque Country | 18 | 6.3 |

| Canary Islands | 14 | 4.9 |

| Region of Murcia | 14 | 4.9 |

| Valencian Community | 11 | 3.8 |

| Community of Madrid | 11 | 3.8 |

| Aragon | 9 | 3.1 |

| Navarre | 8 | 2.8 |

| Andalusia | 7 | 2.4 |

| Extremadura | 4 | 1.4 |

| Galicia | 4 | 1.4 |

The instrument used was the Teacher’s Talent Management Assessment Test (TTMAT) (Liechti & Sesé, 2024), which provides valid and reliable scores on TTM in schools. The test comprises 61 items presented as declarative statements, each rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 6 = Strongly agree. This response format was chosen to discourage central responses associated with social desirability or indecision, thereby encouraging respondents to take a more definitive position. These items form a latent structure of six factors: attraction (6 items), selection-culture (14 items), development-succession (10 items), retention-climate (15 items), evaluation (9 items), and knowledge management (7 items). Reliability analyses were conducted for each dimension using both Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω), together with Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The results revealed consistently high reliability coefficients across all dimensions: attraction (α = .93, ω = .93, CR = .92, AVE = .70), selection-culture (α = .95, ω = .95, CR = .95, AVE = .60), development-succession (α = .96, ω = .96, CR = .95, AVE = .70), retention-climate (α = .94, ω = .95, CR = .91, AVE = .57), evaluation (α = .97, ω = .97, CR = .97, AVE = .77), and knowledge management (α = .90, ω = .89, CR = .86, AVE = .55). These high coefficients indicate excellent internal consistency across all dimensions of the instrument.

In addition to the TTMAT, the study protocol considered several other variables for differential analyses, including age, self-reported sex (men and women), number of lines as a counting variable, type of centre (pre-school, primary, secondary), and ownership of the centre (public, subsidized, or private). The protocol also assessed whether the centre has a Pedagogical Innovation Project (PIP) and whether it collaborates with a university (UCOL) or develops European Educational Programmes (PEU). These variables were included to provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors potentially influencing TTM in the schools studied.

ProcedureThe TTMAT instrument was administered using Google Forms as the application tool. A direct link was generated to a protocol that included the TTMAT questionnaire items and related external variables. The protocol’s first screen provided information about the study objectives and instructions for proper completion. To maximize school participation, given that the sampling unit was the school (represented by one management team member), a reminder message encouraging participation was scheduled for approximately three weeks after the initial mailing. The recruitment process was designed so that each school independently selected the respondent, which we believed would best reflect the institution’s perspective. Data collection took place in the first half of 2020, coinciding with COVID-19 declaration. Although the study was not submitted for review by an ethics committee, both its design and implementation regarding data collection and processing consistently adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the applicable data protection legislation. When the management team of each institution agreed to participate by completing the questionnaire, they were presented on the first screen with comprehensive information concerning data processing and the anonymous nature of the protocol. The questionnaire was specifically designed to ensure complete anonymity, making it impossible to identify the responses of any individual institution. The instructions clarified that completion of the questionnaire would be considered as providing informed consent for participation in the study. Additionally, it was made clear that participants were free to stop completing the questionnaire at any point, without any obligation to continue.

Statistical analysesThe data matrix was initially screened for quality and completeness. Fourteen cases were excluded due to outliers identified across the six TTMAT dimensions, resulting in a final sample of 288 schools. No imputation was necessary, as there were no missing data. Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine the univariate distribution of scores for each TTMAT dimension. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality assumption for each dimension. For the comparison of mean scores across the six TTMAT dimensions, we employed a one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Prior to conducting the ANOVA, the assumption of sphericity was evaluated using Mauchly’s test; in the case of violation, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. The effect size for the ANOVA was reported using partial eta squared. To further explore pairwise differences between dimensions, Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc comparisons were performed, with Cohen’s d calculated to quantify the magnitude of these effects.

Given that the normality assumption was not strictly met for all dimensions, complementary non-parametric analyses were conducted. The Friedman test was used as a non-parametric alternative to repeated measures ANOVA, and Durbin-Conover tests were applied for post hoc pairwise comparisons. Correlations between dimension scores were assessed using both Pearson’s r (for normally distributed dimensions) and Spearman’s rho (for non-normally distributed dimensions). To identify distinct school profiles based on TTMAT scores, a K-means cluster analysis was performed using the Hartigan-Wong algorithm on standardized dimension scores. The optimal number of clusters was determined using the Gap statistic, following the criterion of selecting the smallest k that maximizes the Gap within its standard deviation (Seol, 2025). After cluster identification, we examined differences between clusters with respect to both TTMAT dimensions and contextual variables. For continuous variables, independent samples t-tests were used, with the assumption of homogeneity of variances assessed via Levene’s test. For categorical variables, contingency table analyses were conducted using Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The strength of associations in contingency analyses was quantified using Cramer’s V (Meyer et al., 2023). All statistical analyses were conducted using JAMOVI version 2.6.13 (The jamovi project, 2024).

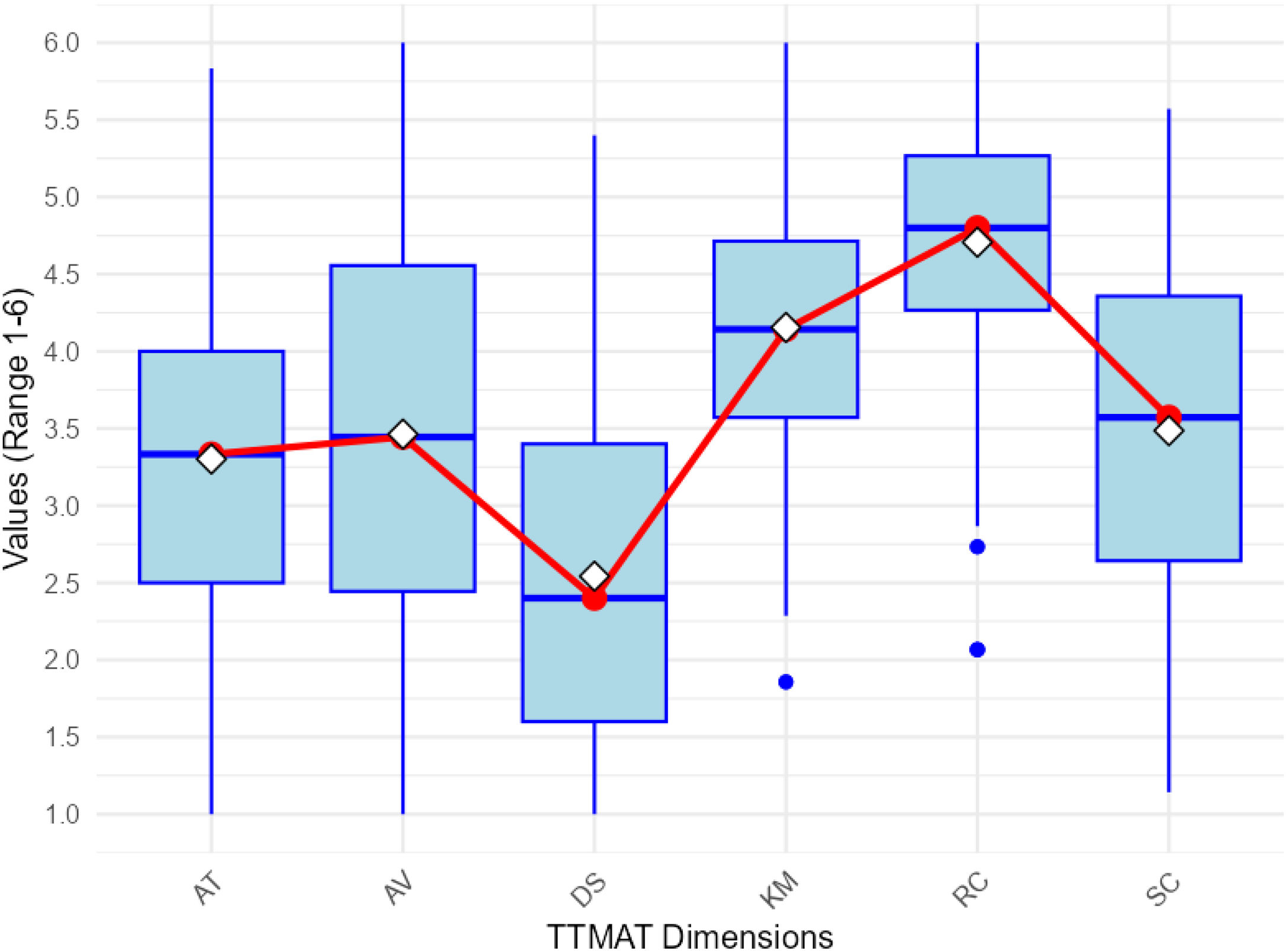

ResultsDescriptive analysis for TTMAT dimensionsFigure 2 shows the average scores (ranging from 1 to 6) for the six TTMAT dimensions. Spanish schools scored lowest in development-succession (M = 2.54, SD = 1.10), which, along with retention-climate (p = .019), showed slight deviations from normality. The dimensions of attraction (M = 3.30, SD = 1.08, p = .114), evaluation (M = 3.46, SD = 1.28, p = .221), and selection-culture (M = 3.49, SD = 1.07, p = .076) were normally distributed and had intermediate scores. In contrast, knowledge management (M = 4.15, SD = 0.85, p = .412) and retention-climate (M = 4.71, SD = 0.75) achieved the highest scores, both exceeding 4 points.

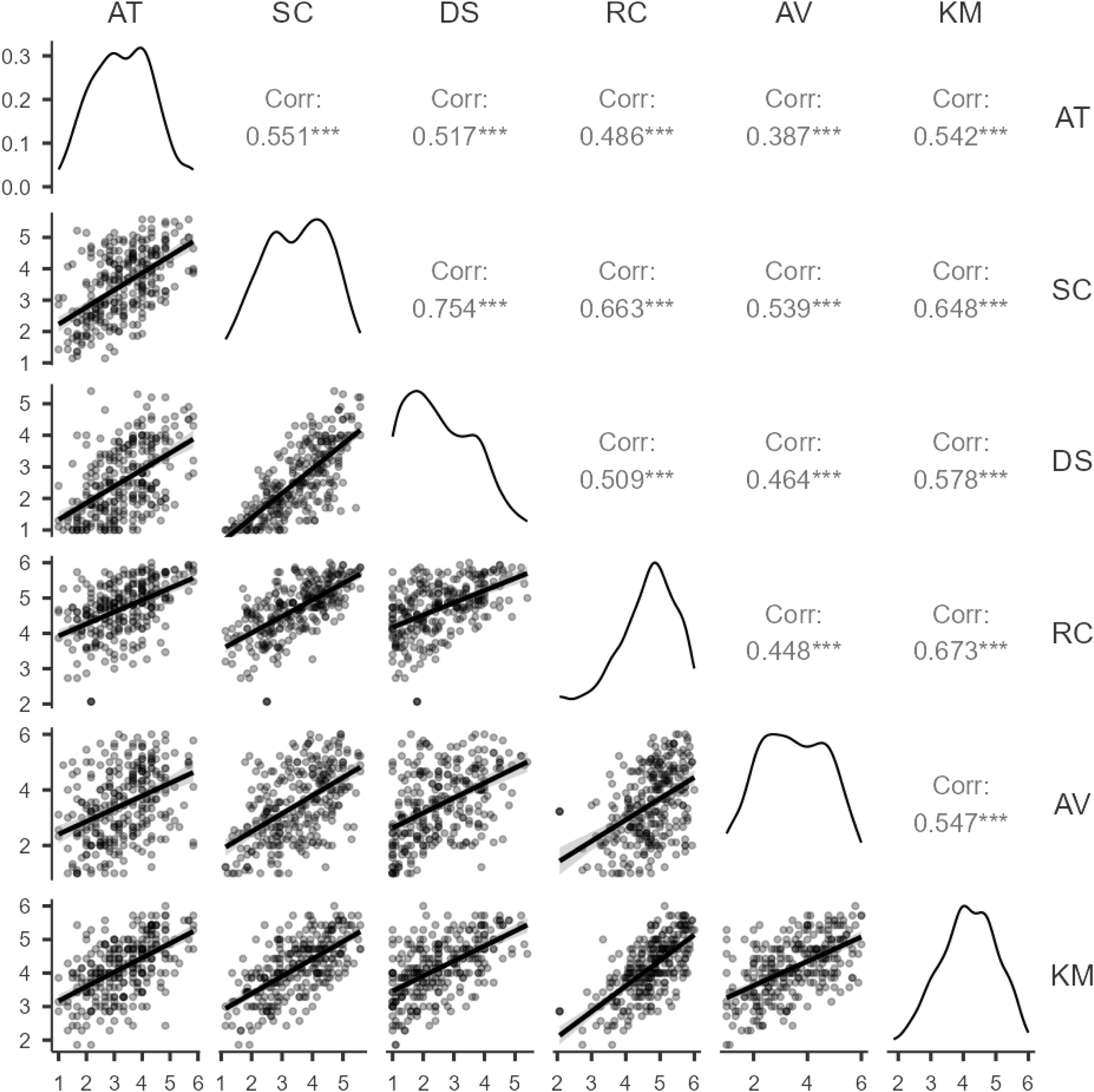

A repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant differences among the six dimensions (F = 314.83, df = 3.92, 727.48, p < .001, partial η2 = 52.3%), with sphericity violated (Mauchly’s W = 0.47, p < .001; Greenhouse-Geisser ε = .78). These results were supported by the non-parametric Friedman’s Q-test (Q = 763.20, df = 5, p < .001). Bonferroni post hoc comparisons showed that 13 out of 15 pairs were statistically significant, except for attraction vs. evaluation (p = .579) and selection-culture vs. evaluation (p = 1.00). The Durbin-Conover test confirmed these findings, with only the selection-culture vs. evaluation comparison non-significant (p = .697). Cohen’s d ranged from 0.14 to 2.00, with 71.4% of significant effects exceeding 0.80, indicating large effect sizes. Finally, all estimated Pearson correlations among the six dimensions of the GTD (Figure 3) were statistically significant (p < .001), ranging from .39 (between attraction and evaluation) to .75 (between selection-culture and Development-Succession). The average correlation was .55, increasing to .56 when calculated using Spearman’s coefficient.

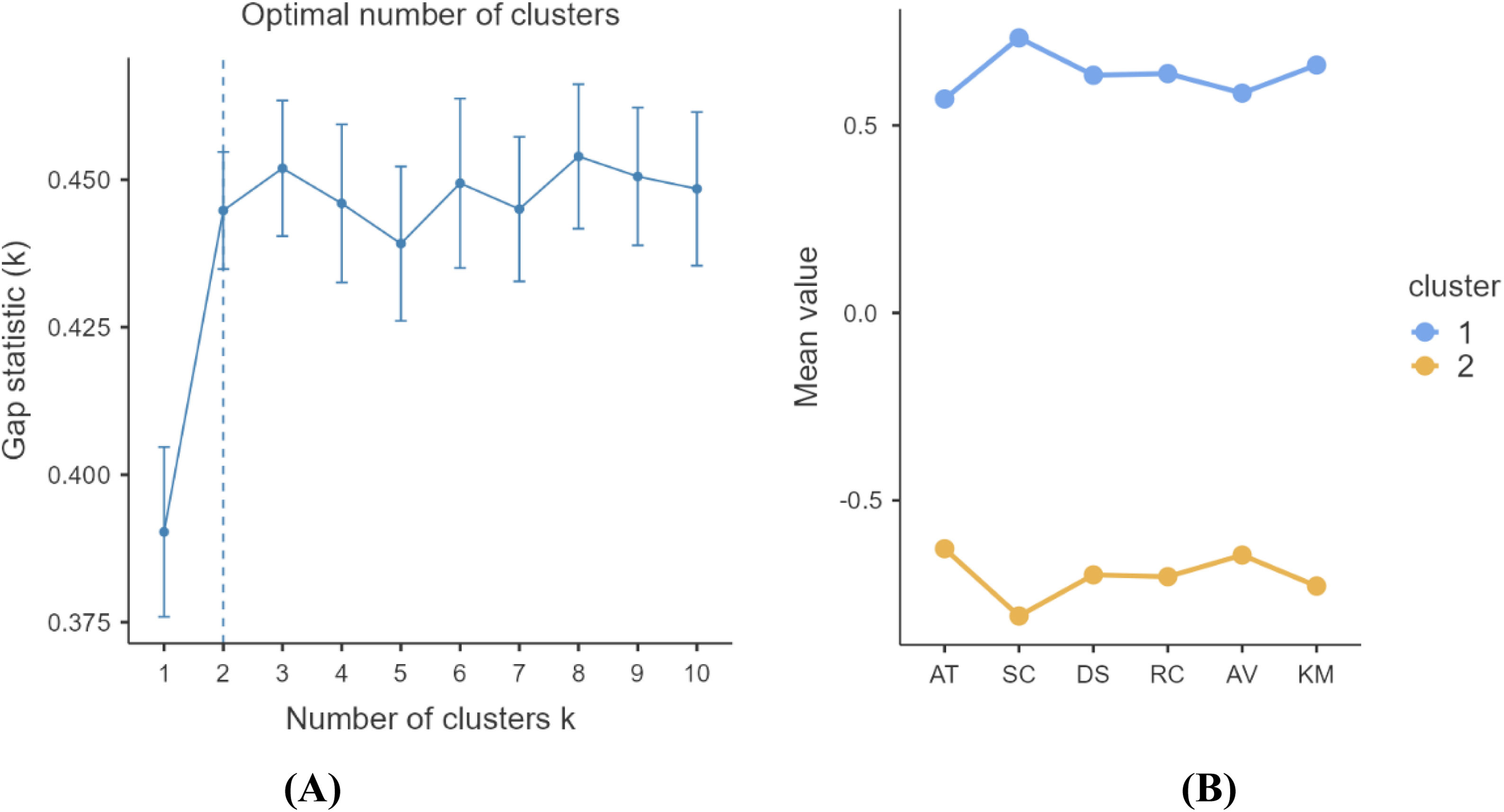

Cluster analysis using TTMAT dimensionsCluster analysis identified two groups (n = 151 and n = 137), with the Gap Statistic indicating k = 2 as the most parsimonious and interpretable solution (Figure 4A). Cluster 1 accounted for 478.66 units of variation and Cluster 2 for 465.09, with a between-cluster sum of squares of 778.25 out of a total of 1722.00, showing that a substantial proportion of variance was explained by differences between clusters. Figure 4B presents the standardized mean profiles for both clusters across the six TTMAT dimensions. Cluster 1 showed consistently high scores, ranging from 0.57 to 0.73 standard deviations above the mean, while Cluster 2 exhibited lower scores, from -0.63 to -0.81 standard deviations below the mean. This pattern highlights a clear distinction between the clusters, with Cluster 1 representing schools with generally higher TTMAT scores and Cluster 2 representing those with lower scores across all dimensions.

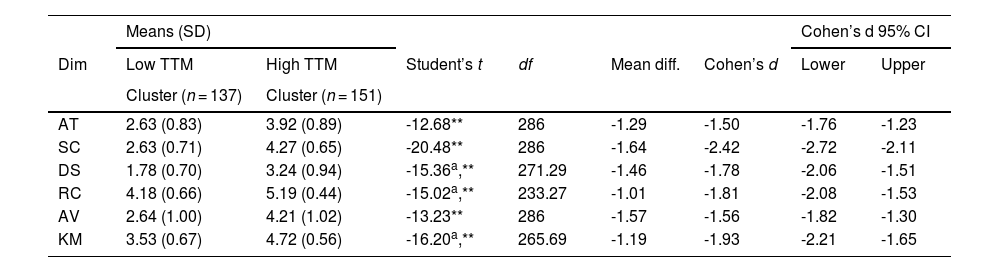

Differential analysis across TTMAT clustersTable 2 presents the comparison of the six TTMAT dimensions between the high and low TTM clusters. Statistically significant differences were found across all dimensions (p < .001), with the high TTM cluster consistently showing higher scores. Effect sizes were substantial, with Cohen’s d ranging from 1.50 (attraction) to 2.42 (selection-culture), indicating very large differences between clusters on every dimension.

Independent samples t-tests comparing high and low TTM clusters across TTMAT dimensions

| Means (SD) | Cohen’s d 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dim | Low TTM | High TTM | Student’s t | df | Mean diff. | Cohen’s d | Lower | Upper |

| Cluster (n = 137) | Cluster (n = 151) | |||||||

| AT | 2.63 (0.83) | 3.92 (0.89) | -12.68** | 286 | -1.29 | -1.50 | -1.76 | -1.23 |

| SC | 2.63 (0.71) | 4.27 (0.65) | -20.48** | 286 | -1.64 | -2.42 | -2.72 | -2.11 |

| DS | 1.78 (0.70) | 3.24 (0.94) | -15.36a,** | 271.29 | -1.46 | -1.78 | -2.06 | -1.51 |

| RC | 4.18 (0.66) | 5.19 (0.44) | -15.02a,** | 233.27 | -1.01 | -1.81 | -2.08 | -1.53 |

| AV | 2.64 (1.00) | 4.21 (1.02) | -13.23** | 286 | -1.57 | -1.56 | -1.82 | -1.30 |

| KM | 3.53 (0.67) | 4.72 (0.56) | -16.20a,** | 265.69 | -1.19 | -1.93 | -2.21 | -1.65 |

AT = Attraction, SC = Selection-Culture, DS = Development-Succession, RC = Retention-Climate, AV = Evaluation, KM = Knowledge Management.

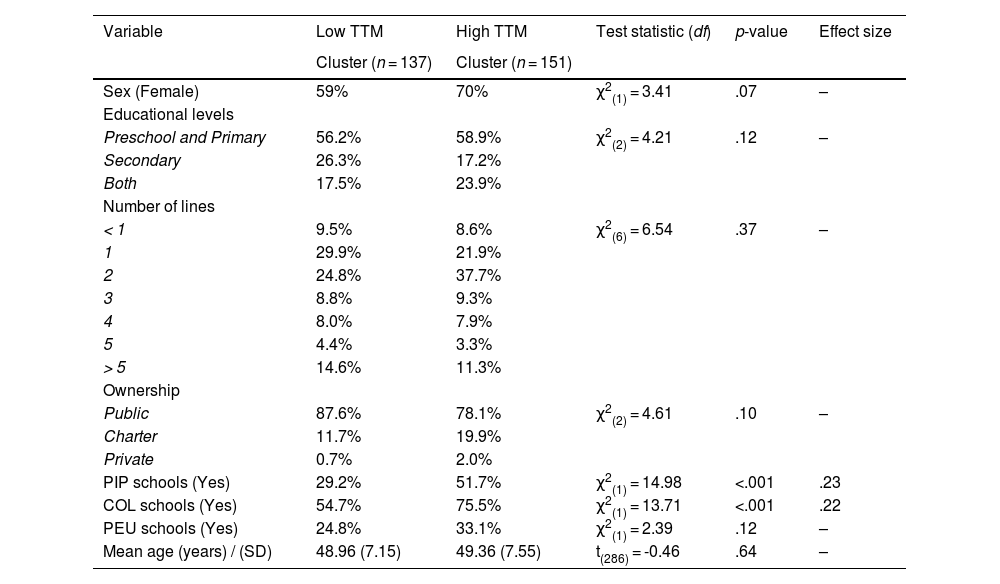

Finally, we also analyzed the differential profiles of the two clusters with respect to the study’s variables of interest: self-reported sex and age of each school’s participant, the number of school lines, type of school, ownership, and the presence of COL, PIP, and PEU schools. Table 3 shows that the high TTM cluster had a significantly greater proportion of PIP schools (52% vs. 29%; χ2 = 14.07, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .23) and UCOL schools (75% vs. 55%; χ2 = 12.81, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .22) compared to the low TTM cluster. No significant differences were found between clusters for participant sex, age, number of school lines, ownership, or the percentage of PEU schools.

Comparison of study variables between High and Low TTM clusters

| Variable | Low TTM | High TTM | Test statistic (df) | p-value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster (n = 137) | Cluster (n = 151) | ||||

| Sex (Female) | 59% | 70% | χ2(1) = 3.41 | .07 | – |

| Educational levels | |||||

| Preschool and Primary | 56.2% | 58.9% | χ2(2) = 4.21 | .12 | – |

| Secondary | 26.3% | 17.2% | |||

| Both | 17.5% | 23.9% | |||

| Number of lines | |||||

| < 1 | 9.5% | 8.6% | χ2(6) = 6.54 | .37 | – |

| 1 | 29.9% | 21.9% | |||

| 2 | 24.8% | 37.7% | |||

| 3 | 8.8% | 9.3% | |||

| 4 | 8.0% | 7.9% | |||

| 5 | 4.4% | 3.3% | |||

| > 5 | 14.6% | 11.3% | |||

| Ownership | |||||

| Public | 87.6% | 78.1% | χ2(2) = 4.61 | .10 | – |

| Charter | 11.7% | 19.9% | |||

| Private | 0.7% | 2.0% | |||

| PIP schools (Yes) | 29.2% | 51.7% | χ2(1) = 14.98 | <.001 | .23 |

| COL schools (Yes) | 54.7% | 75.5% | χ2(1) = 13.71 | <.001 | .22 |

| PEU schools (Yes) | 24.8% | 33.1% | χ2(1) = 2.39 | .12 | – |

| Mean age (years) / (SD) | 48.96 (7.15) | 49.36 (7.55) | t(286) = -0.46 | .64 | – |

This study offers insights into the current state of TTM in Spanish schools, highlighting both strengths and areas for improvement. Importantly, this is the first study conducted in Spain specifically focused on TTM, which provides a basis for understanding the challenges and opportunities within the Spanish educational context. By establishing an initial framework for TTM practices, this research may contribute to future discussions and efforts aimed at enhancing talent management strategies in schools across the country.

Overall TTM performanceOur analysis of the six dimensions of the TTMAT provides a nuanced understanding of TTM practices in Spanish schools. The highest scores were observed in the retention-climate indicating that Spanish schools are relatively effective in fostering positive work environments. According to Anlesinya and Amponsah-Tawiah (2020), schools seem to be enrolled in practices that contribute to organizational well-being. Something similar happens with knowledge management. Schools presume to be committed because they promote sharing knowledge among employees (Keramati & Azimi, 2023), assuring it an essential resource to organizational transformation (Ramaditya et al., 2022).

The lower scores in the development-succession, attraction, evaluation, and selection-culture dimensions highlight significant room for improvement. These can be interpreted from two perspectives; in one hand, these dimensions seem echo the current needs in the Spanish education system, which are currently under debate. This means that the present selection model, needs a deep revision, considering both personal (socioemotional) and interpersonal (teamwork) competences (Gratacós et al., 2024). In terms of evaluation, seems to reflect the current Spanish situation of non-existence performance assessment linked to the professional competences framework (Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2022). In case of development-succession schools may echoes the lack of professional development and its articulation through a career plan (Rupérez, 2021). In terms of attraction, it is possible that schools understand their commitment by disseminating their school's good practices without attaching it to the selection process because they are not enrolled in.

In other hand, we should consider that maybe these dimensions appear to be implemented outside TTM paradigm, meaning that talent should be envisaged as one of the organization’s core values. This includes identifying potential, fostering individual development plans, using appropriate tools to classify profiles, employing performance appraisals as strategies to build talent loyalty, and enhancing the institution’s reputation.

The particularly low score in the development-succession dimension can reveal different interpretations. Beyond the lack of a career plan maybe schools do not identify themselves with the philosophy of high-performance development pathways as Picazo (2004) consider be addressed by individual development pathways. On the other hand, succession can be affected by a lack of knowledge, need or temporary recruitment, which in certain centers or specialties causes a high turnover, making it difficult to implement succession plans.

Cluster analysis: High vs. low TTM schoolsOur data reveal two distinct clusters: high TTM and low TTM. These results are significant as they provide a clear picture of talent management practices across Spanish schools and highlight their disparity. The consistently higher scores across all dimensions in the high TTM cluster suggest that some schools have successfully implemented comprehensive talent management strategies. The notable differences between the two clusters across all dimensions, with large effect sizes, emphasize the substantial gap in TTM practices. These results align with what previous literature suggests: that context matters (Gallardo-Gallardo et al., 2019) because as Abid and Polo (2024) say, TTM practices need to be contextualize attending to their organizational context and as we previously discuss, the Spanish educational context reflects a huge disparity. While some schools have more independence to implement TTM practices because of their ownership condition, others are normatively regulated being more restricted in the TTM context. This disparity underscores the need for targeted interventions and policy measures aimed at improving the performance of low TTM schools and reducing the inequality in talent management practices across the education system. Consequently, high TTM schools could serve as models for best practices within the Spanish education system.

Key factors for boosting TTMAccording to previous literature (Tabancalı et al., 2017), demographic aspects were not identified as key variables in differential analyses to understand the factors influencing TTM. Interestingly, our analysis found that demographic factors such as teacher gender, age, and school characteristics like the number of lines or ownership type were not significantly associated with TTM performance. This suggests that effective talent management practices can be implemented regardless of these contextual factors. However, it is noteworthy that the high TTM cluster showed a higher proportion of schools with improvement plans and university collaborations.

No previous studies report these findings. From our perspective, this may reinforce the claims in the literature that political priorities to enhance talent development are crucial (Behera & Behera, 2024). Our data support the idea that a stronger commitment to research or innovation fosters talent management practices in Spanish schools. This association suggests that effective collaboration with universities through pedagogical innovation projects or other initiatives can enhance a school’s capacity to implement effective TTM practices or improve existing plans. Although no statistically significant differences were found in the percentage of PEU schools between TTM clusters, this result remains important. It may indicate that the European connection, within the framework of these projects, between schools from different public employment access systems, leads them to adopt strategic talent management policies, with Spanish institutions appearing to be influenced by this trend.

Limitations and future directionsThis study has several limitations. First, the use of convenience sampling, due to the inability to implement a complete stratified random sampling process for the reference population, resulted in very low sample sizes for some autonomous communities, which may have introduced representativeness biases. A second limitation is that only one participant per school completed the protocol, with the selection left to each school’s discretion. This may have limited the diversity of perspectives, especially concerning variables such as age and gender within management teams. Future research should consider including multiple staff members per school to capture a more comprehensive and representative view. Third, we did not explore the effect of external variables on TTM, which has been examined in previous studies (Cabrera, 2015; Santa Cruz, 2014). The main reason for this decision was to avoid increasing the complexity of the protocol and to reduce administration time. Also, a potential limitation is that data collection took place during a period that may have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we do not expect this to have significantly affected the results, as TTM was assessed from an organizational culture perspective, which is generally stable over time (Chatman & O’Reilly, 2016; Schein, 2010). While we assume that school board representatives reflected the school’s usual TTM culture rather than pandemic-specific circumstances, some contextual influence cannot be entirely ruled out and should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Future studies could explore criterial variables such as burnout or job satisfaction. Finally, future research should also investigate the causal relationships between TTM practices, leadership, and school performance outcomes. Additionally, exploring the specific strategies employed by high TTM schools that contribute to their success would be valuable. Longitudinal studies could also provide insights into the long-term effects of improved TTM practices on teacher attraction, retention, student outcomes, and overall school performance.

Conclusions and implicationsThis study represents the first empirical effort to measure TTM in Spain. Our findings reveal that Spanish schools exhibit strengths in certain aspects of TTM, particularly in retention-climate and knowledge management. However, significant areas for improvement remain, especially in teacher development and succession. These findings have several implications in terms of real settings in both educational policies and specific actions of schools.

Educational policies implicationsAn important implication is linked to the proposals for improvement the teaching profession in Spain (Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2022) attached to the selection model, the impetus of performance evaluation or the creation of professional career. These dimensions are currently designed for the entire teaching staff, with no distinction for the potential. Therefore, it would be important to contextualize these initiatives in the TTM paradigm to boost other dimensions such as attraction, succession and talent culture. This could be addressed by the creation of a high-performance teaching competence area specialized in TTM within educational administration. It could be a team that, in the framework of each school's own context (Abid & Polo, 2024), would apply the paradigm linked to TTM. Among its objectives: (a) Foster talent leadership; (b) Principals guidance on the culture of talent; (c) Implementation of a TTM program; (d) Coordination with schools in the TTM implementation and monitoring process; (e) Targeted interventions for low TTM schools to improve current talent management practices; and (f) Drawing out TTM performance metrics.

Educational implicationsThe main implication in schools is based on stop hiding potential talent (Ramaditya et al., 2022) and building a culture of talent (Davies & Davies, 2011). Schools will be able to find out their areas for improvement following the application of the TTMAT (Liechti & Sesé, 2024) guided by the specialized TTM administration team. It would be interesting to review for those schools with better scores in retention-climate and knowledge management, whether these actions are contextualized in the philosophy of talent management, i.e. whether they align talent and school interests (Davies & Davies, 2011), promote the well-being of talent, their commitment to the school (Anlesinya & Amponsah-Tawiah, 2020). There is also a need to review scores in areas such as selection-culture, evaluation and attraction. In the case of evaluation, because performance evaluation does not currently exist in the Spanish context and is applicable in the TTM paradigm. So, schools can initiate this practice. Selection-culture needs to be reviewed to identify whether Spanish schools practice the identification and ranking of potentials within the school culture in which the teacher is one of the cornerstones. Finally, it would be necessary to conduct schools in development-succession to consider the creation of a specialized talent development area and the implementation of individualized development programs (Picazo, 2004) as well as the creation of succession plans to avoid talent loss.

By addressing these issues and implementing targeted strategies, Spain can take significant steps toward improving TTM practices, ultimately enhancing teacher effectiveness, retention, and the overall quality of education. These efforts can transform schools into thriving, innovation-driven environments where teachers feel supported, valued, and equipped to deliver their best work. By fostering a culture that prioritizes the development and retention of talented educators, Spain could not only elevate its teaching standards but also inspire future generations of educators to join the profession and contribute to its growth. This vision requires sustained effort and collaboration among the administration and schools. The rewards, such as a more effective, engaged, and empowered workforce, will undoubtedly be worth the investment.

ORCID IDsNathalie Liechti: 0000-0003-1776-1693

Albert Sesé: 0000-0003-3771-1749.

Autthor contributionNathalie Liechti: conceptualization, project administration, writing-original draft, writing-review, and visualization. Albert Sesé: methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing-review and editing, supervision.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.