To explore sleep dysfunction in clinically stable patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) and to identify sleep disturbances and uncover their associated risk factors.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted, involving the recruitment of 306 patients with MG from three MG centers. Participants completed an online self-report questionnaire covering demographic variables, clinical characteristics, and assessments using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scale, STOP-Bang scale, Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15 (MG-QOL 15) scale, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), to evaluate sleep quality among patients with MG.

ResultsApproximately 68% of patients with MG presented sleep disturbances (PSQI ≥6). Univariate analysis revealed that age, lower education level (≤12 years), being single, late disease onset (>55 years old), generalized subtype, myasthenia crisis, positivity for AChR antibodies, thymoma, thymectomy, and type B thymoma were risk factors for sleep dysfunction in patients with MG. Within the sleep disturbances group, 51% of patients scored ≥3 on the STOP-Bang scale, indicating a higher risk of obstructive sleep apnea. PSQI global scores showed significant linear correlations with MG-QOL 15, STOP-Bang, PHQ-9, and SAS scores (P<.001). Multivariate analysis revealed that sex, marital status, STOP-Bang score, SAS score, and MG-QOL 15 score were correlated with the PSQI score.

ConclusionSleep disturbances are prevalent among patients with MG, even in clinically stable cases. Psychological factors such as anxiety and health-related quality of life warrant increased attention in the management of these patients.

El objetivo de este trabajo es explorar la disfunción del sueño entre pacientes con miastenia gravis (MG) clínicamente estables y tratar de identificar las alteraciones del sueño y descubrir sus factores de riesgo asociados.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio transversal que incluyó la selección de 306 pacientes con MG de 3 centros de MG. Los participantes completaron un cuestionario de autoinforme en línea que incluía datos demográficos, características clínicas y evaluaciones mediante el Índice de Calidad del sueño de Pittsburgh (PSQI), la escala STOP-Bang, el instrumento de 15 ítems para medir la calidad de vida en la MG (MG-QoL15), el Cuestionario de Salud del Paciente-9 (PHQ-9) y la Escala de Autoevaluación de Ansiedad (SAS) para evaluar la calidad del sueño entre los pacientes con MG.

ResultadosAproximadamente el 68% de los pacientes con MG experimentaron alteraciones del sueño (PSQI≥6). El análisis univariante reveló que la edad avanzada (>60 años), el nivel educativo inferior (≤12 años), no tener pareja, el inicio tardío de la enfermedad (>55 años), el subtipo generalizado, la crisis de miastenia, el anticuerpo AChR positivo, el timoma, la timectomía y el timoma patológico de tipo B eran factores de riesgo de disfunción del sueño en pacientes con MG. Dentro del grupo de trastornos del sueño, el 51% de los pacientes obtuvo una puntuación ≥3 en la escala STOP-Bang, lo que indica un mayor riesgo de apnea obstructiva del sueño. Las puntuaciones globales del PSQI mostraron correlaciones lineales significativas con las puntuaciones de MG-QoL15, el STOP-Bang, el PHQ-9 y la SAS (p<0,001). El análisis multivariante reveló que el sexo, el estado civil, la puntuación STOP-Bang, la puntuación SAS y la puntuación MG-QoL15 mostraban correlaciones con la puntuación PSQI.

ConclusionesLos trastornos del sueño son prevalentes entre los pacientes con MG, incluso en casos clínicamente estables. Factores psicológicos como la ansiedad y la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud merecen una mayor atención en el tratamiento de estos pacientes.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune neurological disorder characterized by acquired dysfunction in transmission at the neuromuscular junction mediated by pathogenic autoantibodies, notably acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibodies. With global prevalence estimated to surpass 700000 individuals, MG incidence demonstrates variability based on age, sex, and ethnicity. In China, for instance, the age- and sex-adjusted incidence rate was reported as 0.68 per 100000 person-years in 2020.1 MG primarily manifests as skeletal muscle weakness and fatigue, and can involve the oropharyngeal muscles or diaphragm, resulting in respiratory distress.2 Treatment modalities for MG encompass a range of interventions, including acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, plasma exchange, traditional immunosuppressants, and novel monoclonal antibodies (complement inhibitors and neonatal Fc receptor blockers).3–5

Traditionally viewed as a condition primarily affecting motor function, MG exhibits various non-motor symptoms, particularly in cases associated with thymoma. These symptoms include neuromyotonia, limbic encephalitis, pure red cell aplasia, alopecia areata, taste disorders, myocarditis, and other forms of immunodeficiency, likely stemming from an abnormal T-cell repertoire associated with thymomas.6 Additionally, non-motor symptoms such as sleep disorders, pain, headache, autonomic disturbances, and cognitive and psychosocial issues have been observed, significantly impacting patient management and quality of life.7 Recent reports highlight an increased prevalence of sleep disorders in patients with MG,8 including poor sleep quality, sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), and excessive daytime sleepiness, with profound effects on physical, emotional, and social well-being.

Multiple factors contribute to sleep disturbances in patients with MG, including muscle weakness and fatigue,9,10 especially involving respiratory muscles, which may worsen at night, impacting the sleep cycle. Comorbidities such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and asthma exacerbate SDB in patients with MG. Moreover, disruptions in the acetylcholine mechanism,11 medication side effects,12–14 and psychological factors further influence health-related quality of life, contributing to sleep disturbances. These disturbances can exacerbate weakness and fatigue, leading to difficulties in daily activities and compromising overall quality of life.

This study aimed to explore sleep dysfunction among patients with clinically stable MG. It employed an online self-report questionnaire survey administered at three specialized MG centers in Hubei Province, China, seeking to identify sleep disturbances and uncover their associated risk factors.

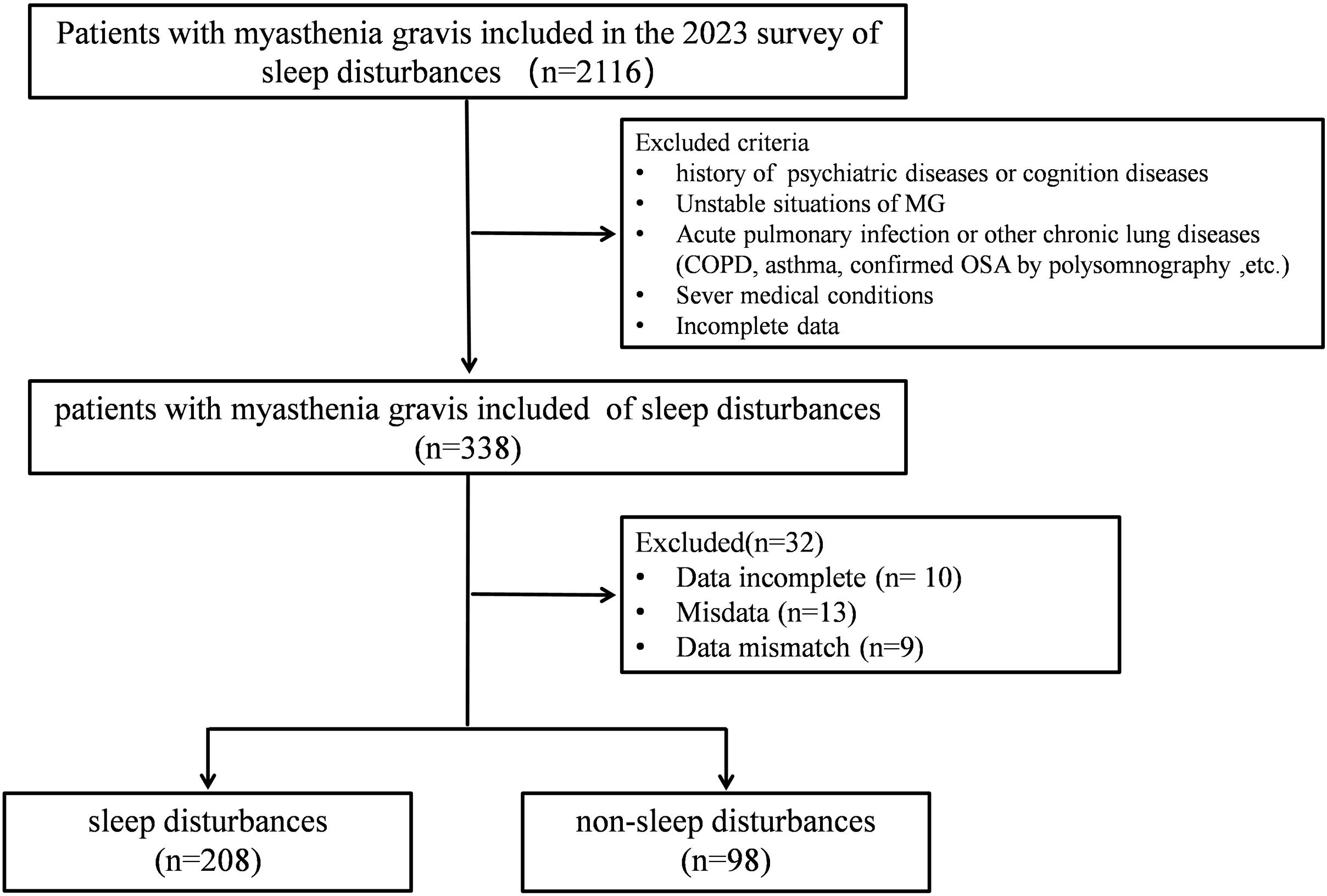

Materials and methodsParticipantsThis study employed a cross-sectional, uncontrolled, descriptive design, recruiting patients from three specialized MG centers (Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College; Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine; and Hubei Aerospace Hospital) during the period from August to November 2023. Patients were diagnosed with MG based on the criteria established by the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA).15,16 Specifically, clinically stable patients with ocular and generalized MG were included in this study. Clinically stable patients were defined as those who had achieved the treatment goal of “minimal manifestations with a dosage of oral prednisolone equivalent below 5mg/day (MM-5 mg).”17 Exclusion criteria were: (1) a history of psychiatric or cognitive diseases; (2) unstable MG status; (3) acute pulmonary infection or other chronic pulmonary diseases (COPD, asthma, OSA confirmed by polysomnography [PSG]); (4) severe medical conditions, such as severe systemic illness or heart disease; and (5) incomplete data collection.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Committee of Clinical Investigation at Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, and Huazhong University of Science and Technology (approval number: TJIRB20220748), in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Study design and methodsPatients with MG were recruited from three MG centers in Hubei Province (China) for inclusion in this survey. A total of 338 patients with MG completed an online questionnaire, self-reporting their recent sleep conditions, emotions, and quality of life for assessment. Thirty-two patients were excluded from subsequent analysis due to incomplete data, resulting in a final analysis of 306 patients (Fig. 1).

The electronic questionnaire addressed three areas: (1) demographic information, including sex, age range, body mass index (BMI), education level, marital status, residence, family monthly income, and treatment costs; (2) clinical characteristics of MG, such as disease duration, onset, subtypes, thymic disease, comorbidities, autoantibodies, and medications; and (3) assessments using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI),18 STOP-Bang scale,19 Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS). The PSQI is a widely used tool for assessing sleep quality over the past month, comprising seven components: sleep disorders, subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, daytime dysfunction, sleep efficiency, total sleep time, and use of sleep medications. A total score of 6 or more indicates the presence of a sleep disorder. The STOP-Bang scale, a rapid screening tool for OSA risk, consists of 8 items related to the clinical features of sleep apnea (snoring, fatigue, observed apnea, hypertension, BMI, age, neck circumference, and male sex). A total score of 3 or higher indicates an increased risk of OSA. The PHQ-9 assesses depressive symptoms, with a score of 5 or more indicating potential depression. The SAS is often used to assess anxiety symptoms in patients. It includes 20 items in total, with a score of 40 or higher indicating anxiety symptoms.

Additionally, the Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15 (MG-QOL 15) questionnaire20 was used to assess overall quality of life in patients with MG. Higher scores on the MG-QOL 15 indicate greater disease severity and poorer quality of life.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses and figure creation were performed using SPSS software (version 27.0; Statistical Product and Service Solutions, USA) and GraphPad Prism (version 9.2.0; GraphPad Software, USA). Descriptive analysis was performed to characterize patients’ demographic and clinical features. Continuous data were expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or as the median and interquartile range (quartiles 1 and 3 [Q1–Q3]), with the t test being employed for comparison, according to data distribution. Count data were presented as frequencies and percentages and analyzed using the chi-square test. The Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the correlation between the PSQI global score and the STOP-Bang scale, PHQ-9, SAS, and MG-QOL 15 score. Multiple stepwise linear regression analysis was performed to identify factors influencing sleep disorders in patients with MG. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P<.05.

ResultsDemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with MGA total of 306 patients with MG participated in this study; approximately two-thirds were women. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Fig. 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample of patients with myasthenia gravis (n=306): distribution of sex (A), age (B), age of onset (C), disease duration (D), and subtype (E). Note: Childhood onset refers to age of onset <18 years. Early onset refers to the age of onset between 18 and 50 years. Late onset refers age of onset age >50 years.

Twenty-three adolescent patients with MG (7.5%) were included in the survey, while the remaining participants were adults. The age of onset for 56% of patients ranged from 18 to 55 years. More than half of the patients with MG (52.3%) had a disease duration exceeding 5 years. Eighty-three patients (27.1%) reported having AChR antibodies, while the antibody type for the remaining patients could not be clearly determined through the online self-reported survey. Thirty-three percent of patients with MG experienced at least one myasthenic crisis. Ninety-nine patients (32.4%) had a history of thymoma, with 28.4% having undergone thymectomy. The most common comorbidity was thyroid disorder, affecting 19.6% of patients. The treatment modalities commonly used for MG management included acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, corticosteroids, traditional immunosuppressants, and biological agents.

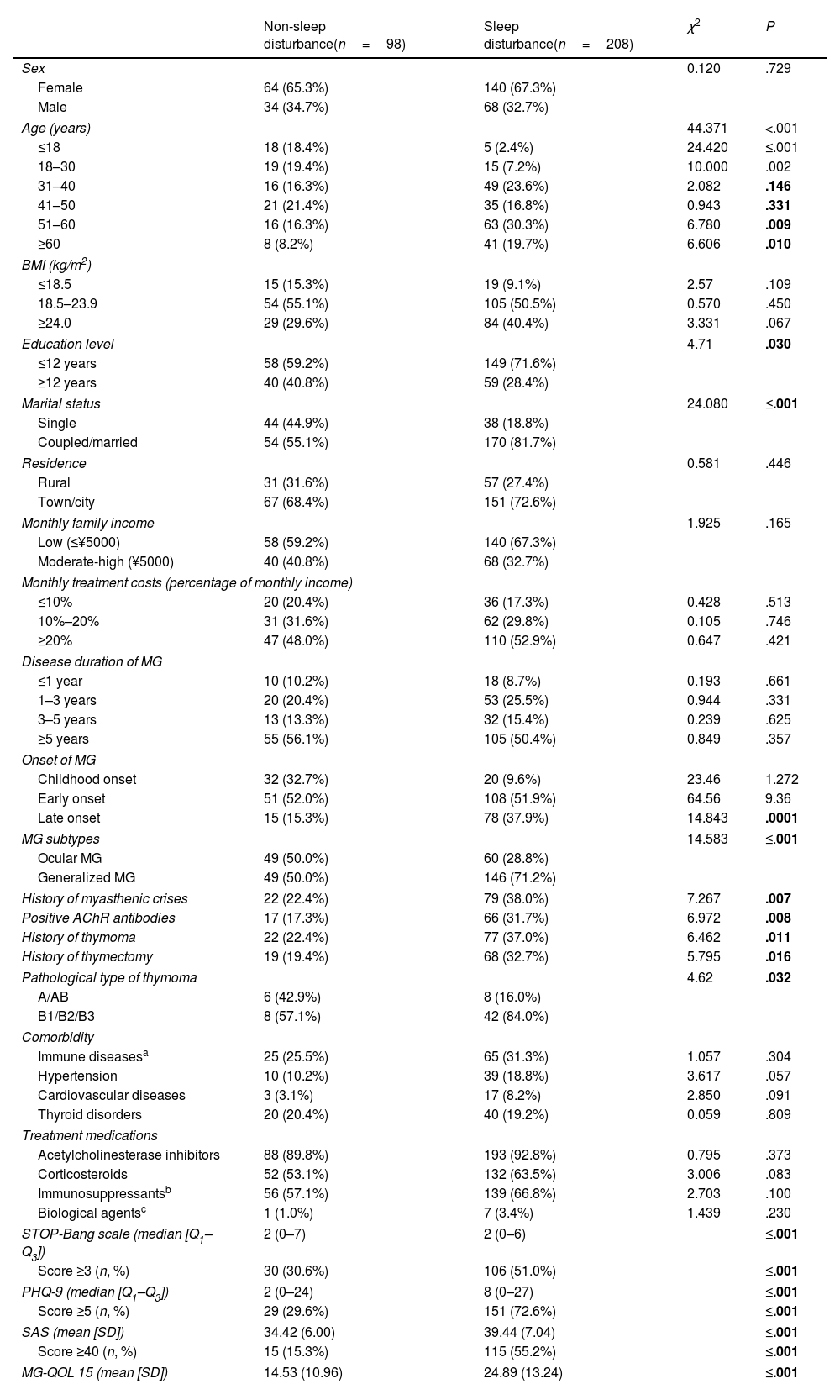

Characteristics and risk factors of sleep disturbances in patients with MGPatients were categorized into groups based on global PSQI scores: the sleep disturbance group (PSQI ≥6) and the non-sleep disturbance group (PSQI <6), comprising 68% (n=208) and 32% of the cohort, respectively. A comparison of clinical characteristics and risk factors between the two groups is presented in Table 1.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with myasthenia gravis between the non-sleep disturbances group and the sleep disturbances group (n, %).

| Non-sleep disturbance(n=98) | Sleep disturbance(n=208) | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.120 | .729 | ||

| Female | 64 (65.3%) | 140 (67.3%) | ||

| Male | 34 (34.7%) | 68 (32.7%) | ||

| Age (years) | 44.371 | <.001 | ||

| ≤18 | 18 (18.4%) | 5 (2.4%) | 24.420 | ≤.001 |

| 18–30 | 19 (19.4%) | 15 (7.2%) | 10.000 | .002 |

| 31–40 | 16 (16.3%) | 49 (23.6%) | 2.082 | .146 |

| 41–50 | 21 (21.4%) | 35 (16.8%) | 0.943 | .331 |

| 51–60 | 16 (16.3%) | 63 (30.3%) | 6.780 | .009 |

| ≥60 | 8 (8.2%) | 41 (19.7%) | 6.606 | .010 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| ≤18.5 | 15 (15.3%) | 19 (9.1%) | 2.57 | .109 |

| 18.5–23.9 | 54 (55.1%) | 105 (50.5%) | 0.570 | .450 |

| ≥24.0 | 29 (29.6%) | 84 (40.4%) | 3.331 | .067 |

| Education level | 4.71 | .030 | ||

| ≤12 years | 58 (59.2%) | 149 (71.6%) | ||

| ≥12 years | 40 (40.8%) | 59 (28.4%) | ||

| Marital status | 24.080 | ≤.001 | ||

| Single | 44 (44.9%) | 38 (18.8%) | ||

| Coupled/married | 54 (55.1%) | 170 (81.7%) | ||

| Residence | 0.581 | .446 | ||

| Rural | 31 (31.6%) | 57 (27.4%) | ||

| Town/city | 67 (68.4%) | 151 (72.6%) | ||

| Monthly family income | 1.925 | .165 | ||

| Low (≤¥5000) | 58 (59.2%) | 140 (67.3%) | ||

| Moderate-high (¥5000) | 40 (40.8%) | 68 (32.7%) | ||

| Monthly treatment costs (percentage of monthly income) | ||||

| ≤10% | 20 (20.4%) | 36 (17.3%) | 0.428 | .513 |

| 10%–20% | 31 (31.6%) | 62 (29.8%) | 0.105 | .746 |

| ≥20% | 47 (48.0%) | 110 (52.9%) | 0.647 | .421 |

| Disease duration of MG | ||||

| ≤1 year | 10 (10.2%) | 18 (8.7%) | 0.193 | .661 |

| 1–3 years | 20 (20.4%) | 53 (25.5%) | 0.944 | .331 |

| 3–5 years | 13 (13.3%) | 32 (15.4%) | 0.239 | .625 |

| ≥5 years | 55 (56.1%) | 105 (50.4%) | 0.849 | .357 |

| Onset of MG | ||||

| Childhood onset | 32 (32.7%) | 20 (9.6%) | 23.46 | 1.272 |

| Early onset | 51 (52.0%) | 108 (51.9%) | 64.56 | 9.36 |

| Late onset | 15 (15.3%) | 78 (37.9%) | 14.843 | .0001 |

| MG subtypes | 14.583 | ≤.001 | ||

| Ocular MG | 49 (50.0%) | 60 (28.8%) | ||

| Generalized MG | 49 (50.0%) | 146 (71.2%) | ||

| History of myasthenic crises | 22 (22.4%) | 79 (38.0%) | 7.267 | .007 |

| Positive AChR antibodies | 17 (17.3%) | 66 (31.7%) | 6.972 | .008 |

| History of thymoma | 22 (22.4%) | 77 (37.0%) | 6.462 | .011 |

| History of thymectomy | 19 (19.4%) | 68 (32.7%) | 5.795 | .016 |

| Pathological type of thymoma | 4.62 | .032 | ||

| A/AB | 6 (42.9%) | 8 (16.0%) | ||

| B1/B2/B3 | 8 (57.1%) | 42 (84.0%) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Immune diseasesa | 25 (25.5%) | 65 (31.3%) | 1.057 | .304 |

| Hypertension | 10 (10.2%) | 39 (18.8%) | 3.617 | .057 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 3 (3.1%) | 17 (8.2%) | 2.850 | .091 |

| Thyroid disorders | 20 (20.4%) | 40 (19.2%) | 0.059 | .809 |

| Treatment medications | ||||

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors | 88 (89.8%) | 193 (92.8%) | 0.795 | .373 |

| Corticosteroids | 52 (53.1%) | 132 (63.5%) | 3.006 | .083 |

| Immunosuppressantsb | 56 (57.1%) | 139 (66.8%) | 2.703 | .100 |

| Biological agentsc | 1 (1.0%) | 7 (3.4%) | 1.439 | .230 |

| STOP-Bang scale (median [Q1–Q3]) | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–6) | ≤.001 | |

| Score ≥3 (n, %) | 30 (30.6%) | 106 (51.0%) | ≤.001 | |

| PHQ-9 (median [Q1–Q3]) | 2 (0–24) | 8 (0–27) | ≤.001 | |

| Score ≥5 (n, %) | 29 (29.6%) | 151 (72.6%) | ≤.001 | |

| SAS (mean [SD]) | 34.42 (6.00) | 39.44 (7.04) | ≤.001 | |

| Score ≥40 (n, %) | 15 (15.3%) | 115 (55.2%) | ≤.001 | |

| MG-QOL 15 (mean [SD]) | 14.53 (10.96) | 24.89 (13.24) | ≤.001 | |

BMI: body mass index; MG: myasthenia gravis; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; SAS: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; MG-QOL 15: Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15; Q1–Q3: quartiles 1 and 3; SD: standard deviation.

Both groups were comparable in terms of sex, BMI, residence, monthly family income, and monthly disease treatment costs (P>.05). In addition, the age (P<.001), lower education level (≤12 years) (P=.03), and being single (P<.001) were associated with sleep dysfunction in patients with MG. Interestingly, sleep dysfunction was also reported in 5 adolescent patients.

Certain clinical characteristics, such as late disease onset (>55 years old), generalized subtype, history of myasthenia crisis, AChR antibody positivity, thymoma, thymectomy, and type B1/B2/B3 thymoma, were identified as risk factors for sleep dysfunction in patients with MG. However, disease duration, comorbidities, and medications showed no significant correlation with sleep dysfunction. Limited patient education and understanding of the disease often led to the adoption of a simplified classification, such as ocular or generalized MG, instead of the MGFA classification. Additionally, due to the difficulty in the precise determination of autoantibodies, the prevalence of anti-AChR antibodies was lower than previously reported.

PSQI components and their correlation with OSA, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in patients with MG and sleep disturbancesFig. 3 and Table S1 present the global and component scores of the PSQI. Among patients with MG experiencing sleep dysfunction, the median (Q1–Q3) global PSQI score was 10 (8–13), significantly higher than that observed in the non-sleep disturbance group (4 [3–5]) (P<.001). All seven PSQI component scores, including subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, daytime dysfunction, sleep efficiency, sleep medication use, and sleep disturbances, were significantly higher in the sleep disturbance group than in the non-sleep disturbance group (P<.001). Additionally, in several subgroups based on disease onset and subtype (as shown in Table S1), both the global and component scores of the PSQI were significantly higher than those of the non-sleep disturbance group (ANOVA, P<.05).

Among all patients with MG, 44.4% (136/306) scored over 3 on the STOP-Bang scale, 58.9% (180/306) scored ≥5 on the PHQ-9 scale, and 42.5% (130/306) scored ≥40 on the SAS scale. Within the sleep disturbance group, 51% of patients scored ≥3 on the STOP-Bang scale, indicating a higher risk of OSA. Moreover, patients experiencing sleep dysfunction were more likely to present comorbid anxiety and depression, as evaluated by the PHQ-9 and SAS scales. Specifically, 72.6% of patients in the sleep disturbance group scored >5 on the PHQ-9 scale, and 55.2% scored >40 on the SAS scale. Furthermore, the MG-QOL 15 questionnaire revealed significantly poorer quality of life in the sleep disturbance group, with a mean (SD) score of 24.89 (13.24), compared to 14.53 (10.96) in the non-sleep disturbance group (P<.001) (Table 1).

Furthermore, correlation analysis across all participants demonstrated significant linear correlations between the global PSQI score and the STOP-Bang (correlation coefficient, r=0.2153), PHQ-9 (r=0.4529), SAS (r=0.4133), and MG-QOL 15 scores (r=0.4432) (P<.001) (Fig. 4).

Correlation between PSQI scores and scores on the STOP-Bang scale, PHQ-9, SAS, and MG-QOL 15 in patients with myasthenia gravis. The sleep disturbances in patients with myasthenia gravis presented a linear correlation with scores on the STOP-Bang scale, PHQ-9, SAS, and MG-QOL 15. PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; SAS: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; MG-QOL 15: Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15.

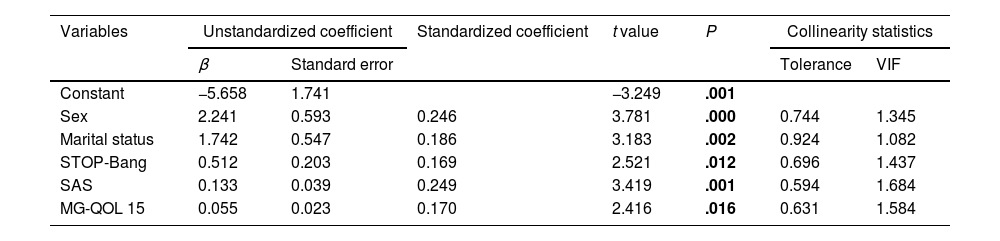

The PSQI scores served as dependent variables, while significant indicators identified in the univariate analysis (namely, sex, age, education, marital status, duration of MG, MG subtype, and AChR antibody positivity) were employed as independent variables. Utilizing a multivariate stepwise regression approach, we examined the relationship between these variables and PSQI scores. Our analysis revealed that sex, marital status, STOP-Bang score, SAS score, and MG-QOL 15 score were closely related to the PSQI score (P<.001). These findings indicate a strong correlation between these factors and the severity of sleep disorders observed in patients with MG. Further details are provided in Table 2.

Multiple linear regression model of PSQI scores in patients with myasthenia gravis.

| Variables | Unstandardized coefficient | Standardized coefficient | t value | P | Collinearity statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Standard error | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| Constant | −5.658 | 1.741 | −3.249 | .001 | |||

| Sex | 2.241 | 0.593 | 0.246 | 3.781 | .000 | 0.744 | 1.345 |

| Marital status | 1.742 | 0.547 | 0.186 | 3.183 | .002 | 0.924 | 1.082 |

| STOP-Bang | 0.512 | 0.203 | 0.169 | 2.521 | .012 | 0.696 | 1.437 |

| SAS | 0.133 | 0.039 | 0.249 | 3.419 | .001 | 0.594 | 1.684 |

| MG-QOL 15 | 0.055 | 0.023 | 0.170 | 2.416 | .016 | 0.631 | 1.584 |

MG-QOL 15: Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15; SAS: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; VIF: variance inflation factor.

*Coefficient of determination R2=0.299; adjusted R2=0.284; F=19.068; P≤.001.

This study sheds light on the prevalence and risk factors associated with sleep disturbances among patients with MG across three MG centers in Hubei Province, China. Utilizing a PSQI cut-off score of ≥6 to define comorbid sleep disorders,18 we found that approximately 68% of patients with MG experienced sleep disturbances; this is consistent with previous studies indicating a prevalence rate ranging from 40% to 68% in clinically stable patients with MG.21–23 While the online questionnaire limited our ability to verify specific sleep conditions or analyze detailed sleep structures using PSG, the PSQI remains a valuable tool in clinical practice due to its comprehensive coverage of relevant sleep quality indicators. Indeed, extensive evidence supports the reliability, validity, and structural validity of the PSQI across various populations, affirming its utility in assessing sleep quality.24

Our analysis of PSQI subscale scores revealed significantly higher scores for subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, daytime dysfunction, and sleep efficiency in the sleep disturbance group compared to the non-sleep disturbance group. Furthermore, we explored risk factors contributing to sleep disturbances in patients in greater detail. Age, lower education level (≤12 years), and being single emerged as demographic characteristics associated with sleep dysfunction. Additionally, there was a notable trend suggesting a higher occurrence of sleep dysfunction among patients with a higher BMI (≥24), which is consistent with previous findings linking obesity to a heightened risk of OSA.25 Notably, we observed a linear correlation between BMI and total STOP-Bang score, further highlighting the utility of the STOP-Bang scale in identifying individuals at risk of OSA.26 In a prospective study involving patients with MG,9 the prevalence of OSA, diagnosed via PSG, was 36%, notably higher than the expected prevalence of 15%–20% in the general population. This elevated prevalence rate has been attributed to oropharyngeal weakness associated with MG.7 In our study, although we excluded previously diagnosed cases of OSA identified through PSG, we did identify subclinical OSA in 44.4% (136/306) of patients screened using the STOP-Bang scale among patients with clinically stable MG. Within the sleep disturbance group, 51% of patients scored ≥3 on the STOP-Bang scale, indicating a higher risk of OSA. Interestingly, other characteristics such as sex, residence, family income, and costs of disease treatment did not demonstrate significant correlations with sleep disturbance in patients with MG.

Based on the clinical characteristics of MG, several factors emerged as risk factors for sleep dysfunction in our study, including late onset of the disease, generalized subtype, myasthenic crisis, anti-AChR antibody positivity, thymoma, thymectomy, and pathological type B thymoma. As reported in prior research, patients with generalized MG were more predisposed to comorbid sleep disorders than those with ocular MG.22 Besides the influence of SDB identified by the STOP-Bang scale in our study, other factors may contribute to sleep disturbances in patients with MG. For instance, previous studies have noted alterations in sleep architecture among patients with MG, characterized by increased slow-wave sleep, shorter REM sleep periods, and shallower sleep on EEG.11 Given that acetylcholine plays a crucial role as a brainstem neurotransmitter involved in REM sleep maintenance, these findings suggest a central disturbance in the acetylcholine mechanism in MG.11 Therefore, nocturnal dysfunction of both the central and peripheral cholinergic systems may contribute to sleep disturbances in patients with MG.8

It has been reported that medications used to manage MG,12–14 such as prednisone, may contribute to dysregulation of the sleep cycle and, consequently, sleep disorders. However, our study did not observe these effects, likely due to the clinically stable condition of our patients with MG, who typically received a low average dosage of prednisolone equivalent per day (normally below 5mg) or had discontinued corticosteroid therapy altogether. This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that the prevalence of corticosteroid-associated adverse events, including sleep disorders, correlates significantly with higher average corticosteroid doses in a dose-dependent manner.27

In our study, anxiety and depression were prevalent among patients with MG, with approximately 59% of patients assessed for comorbidity depression using the PHQ-9 scale, and 42.5% evaluated for anxiety using the SAS scale. Within the sleep disturbance group, the prevalence of depression and anxiety reached notably higher rates of 72.6% and 55.2%, respectively. These findings underscore the susceptibility of patients with MG to psychiatric symptoms, and particularly mood and anxiety disorders,28,29 likely exacerbated by prolonged treatment courses and the use of multiple medications. Moreover, sleep dysfunction had a clear impact on patients’ quality of life, as evaluated with the MG-QOL 15. Further analysis revealed a significant, linear correlation between global PSQI scores and total scores on the MG-QOL 15, STOP-Bang, PHQ-9, and SAS scales. Thus, our study reinforces the intricate relationship between sleep disturbance, reduced quality of life, and heightened levels of anxiety and depression among patients with MG.

Multivariate linear regression analysis revealed that sex, marital status, STOP-Bang score, SAS, and MG-QOL were associated with PSQI score. Univariate analysis did not find a statistically significant association between sex and sleep dysfunction. However, multiple linear regression analysis can be used to control for other confounding factors associated with sleep dysfunction. Notably, our findings suggest that women are more susceptible to sleep disorders, likely attributed to heightened stressors within familiar, societal, and professional realms, particularly evident in those with unfavorable marital status. These stressors may exacerbate psychological strain post-illness, consequently impacting sleep patterns. Furthermore, our study underscores the importance of recognizing undiagnosed OSA identified by the STOP-Bang scale, especially among patients with clinically stable MG. Additionally, our findings emphasize the significance of addressing psychological factors, such as anxiety, and evaluating health-related quality of life in patients with MG, irrespective of their clinical stability status.

LimitationsThis study has some potential limitations that warrant consideration. First, the nature of the online survey restricts the depth of data collection, hindering comprehensive understanding of respondents’ thoughts and feelings. Furthermore, the online format precluded validation of sleep structure disturbances and sleep cycle issues via PSG, despite confirmation by the PSQI. Moreover, as a self-reported survey, subjective assessments may introduce bias, with patients potentially struggling to accurately evaluate their clinical stability or provide precise descriptions. Variations in education levels and disease understanding may further influence responses. In addition, we did not evaluate the correlation between corticosteroid dosage and sleep disturbances, given that most patients were clinically stable with a dosage below 5mg/day, and some had discontinued corticosteroid treatment. Further studies should aim to integrate both objective and subjective evaluations of sleep disorders to enhance our understanding of their impact on patients with MG.

ConclusionSleep disturbances are frequently encountered in patients with MG, particularly among those with stable symptoms. Our findings underscore the importance of addressing psychological factors, such as anxiety, and assessing health-related quality of life in clinically stable patients. By recognizing and addressing these aspects of patient care, healthcare providers can better support the overall well-being of individuals living with MG.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.