Loneliness and related constructs associated with isolation are public health problems with increasing prevalence. The aim of this umbrella was to collate and grade evidence analyzing actual and subjective loneliness as a health risk factor.

Following prospective registration, a systematic search was conducted in Pubmed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Sciences, psycoINFO and Cochrane Library until August 2023. Systematic reviews assessing the association between actual and subjective loneliness with adverse health outcomes were selected. Risk of bias was evaluated using AMSTAR-2 tool. Data were tabulated and synthesis was narrative.

A total of 13 systematic reviews was selected (four included meta-analysis). The methodological quality was critically low in 10 reviews (76.92%) and low in 3 (23.08%). Results showed that loneliness was related to poor well-being and increase the risk of negative mental and physical health. The available data suggested but did not allow the confirmation of a causal association.

Most constructs of loneliness seem to be related to mental and physical health conditions. A preventive strategy ought to be recommended, especially for vulnerable populations.

La soledad, así como sus constructos relacionados asociados al aislamiento son problemas de salud pública con una prevalencia creciente. El objetivo de esta revisión paraguas fue cotejar y clasificar la evidencia científica que analiza la soledad objetiva y subjetiva como factor de riesgo para la salud.

Tras un registro prospectivo, se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Sciences, psycoINFO y Cochrane Library hasta agosto de 2023. Se seleccionaron las revisiones sistemáticas que evaluaban la asociación entre la soledad objetiva y subjetiva con resultados adversos en la salud. El riesgo de sesgo se evaluó mediante la herramienta AMSTAR-2. Los datos se tabularon y la síntesis fue narrativa.

Se seleccionó un total de 13 revisiones sistemáticas (cuatro incluían metaanálisis). La calidad metodológica fue críticamente baja en 10 revisiones (76,92%) y baja en tres (23,08%). Los resultados mostraron que la soledad estaba relacionada con un bienestar deficiente y peor salud mental y física. Los datos disponibles sugerían, pero no permitían confirmar una asociación causal.

La mayoría de los constructos de la soledad parecen estar relacionados con las condiciones de salud mental y física. Debería recomendarse una estrategia preventiva, especialmente para las poblaciones vulnerables.

This has been concern that loneliness, a feeling of isolation that can be real or perceived,1 has been increasing in prevalence among the elderly and adolescents. Awareness was raised during the COVID-19 pandemic when conditions such as living alone, psychiatric disorders and conditions limiting communication were recognized as risk factors.2–4 This relationship between factors and loneliness can be bidirectional, influencing each other negatively.2

Although it may not seem at first sight, but on giving it a little thought, loneliness is a public health problem. Scientific evidence has suggested its association with negative physical health such as cardiovascular diseases,5 chronic pain and obesity.1,6 A constellation of psychiatric and psychosocial dysfunctions has also been associated with loneliness including depression, anxiety disorders, suicidal thoughts, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.2,6 Stress too is a factor, affecting the nervous system leading to negative physical and mental health outcomes.7 A sedentary lifestyle characterized by poor diet, high tobacco and alcohol consumption are considered part of this problem.8–11 In this umbrella review we aimed to collate and grade evidence analyzing loneliness as health risk factor.

MethodsStudy protocolThis umbrella was undertaken according to the protocol prospectively registered on the Open Registries Network (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UW4V8) and reported following the reporting guidelines for overviews of reviews (PRIOR).12

Searches and selection of reviewsThe search question was addressed according to PECOS statement (Population: General Population, Exposure: Perceived and objective loneliness, Comparison: People living in company, Outcome: Physical and mental health condition, Study design: Umbrella review). A systematic search will be done on Pubmed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Sciences, PsycINFO and Cochrane Library until august 2023. Key terms were combined as follow: (Loneliness OR “social isolation”) AND (“Health status” OR “health conditions” OR “health outcomes” OR “well-being”) AND (“Systematic review” OR meta-analysis) and the search strategy was adapted to the characteristics of each database and no filters were used. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis assessing the association between loneliness or similar construct and health conditions and published from inception until august 2023 will be defined by two reviewers independently. A first screening will be done by title and abstract. Then, the full text of potentially eligible records will be assessed. A third reviewer will be consulted in case of doubt or discrepancies.

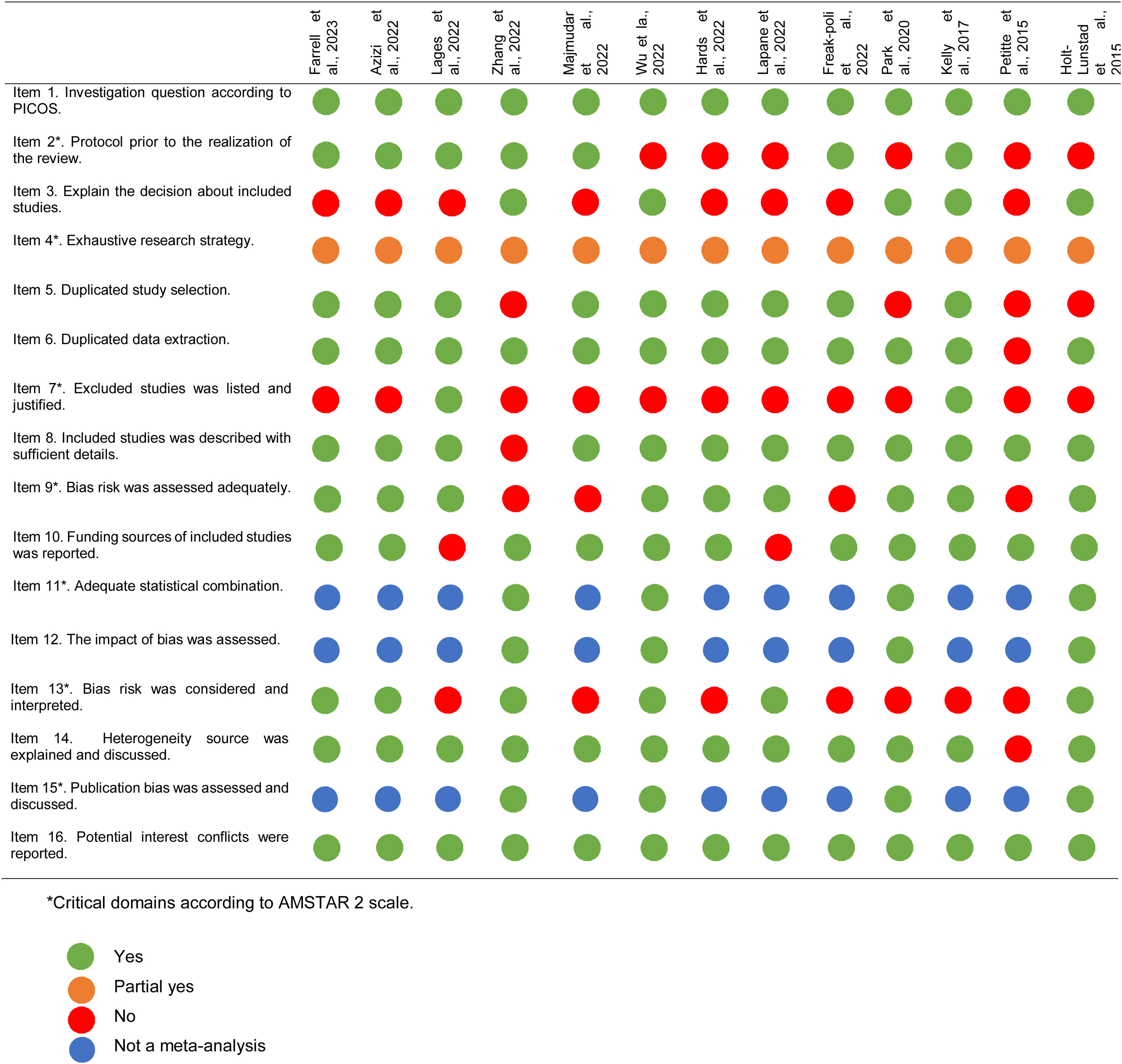

Quality assessment, data extraction and data synthesisFrom each included systematic review and meta-analysis, the following information will be extracted: author and publication year, selection criteria, number of original studies included, population under investigation, participants included in the meta-analysis, exposure measurement, outcome measurement, risk estimates with 95% confidence interval, quality assessment tools used for original studies. The risk of bias of included records will be assessed in pairs using AMSTAR-2 scale. AMSTAR-2 includes a total of sixteen domains. Seven domains are considered as critical. Not meeting these criteria will have a more significant impact on the methodological quality of the reviews. The quality will be classified as: critically low, low, moderate and high according to AMSTAR-2 predefined cut off point.13 Meta-analysis results will be summarized on tables and forest plots. Comparison will be done on a narrative way addressing the epidemiology of loneliness on health status.

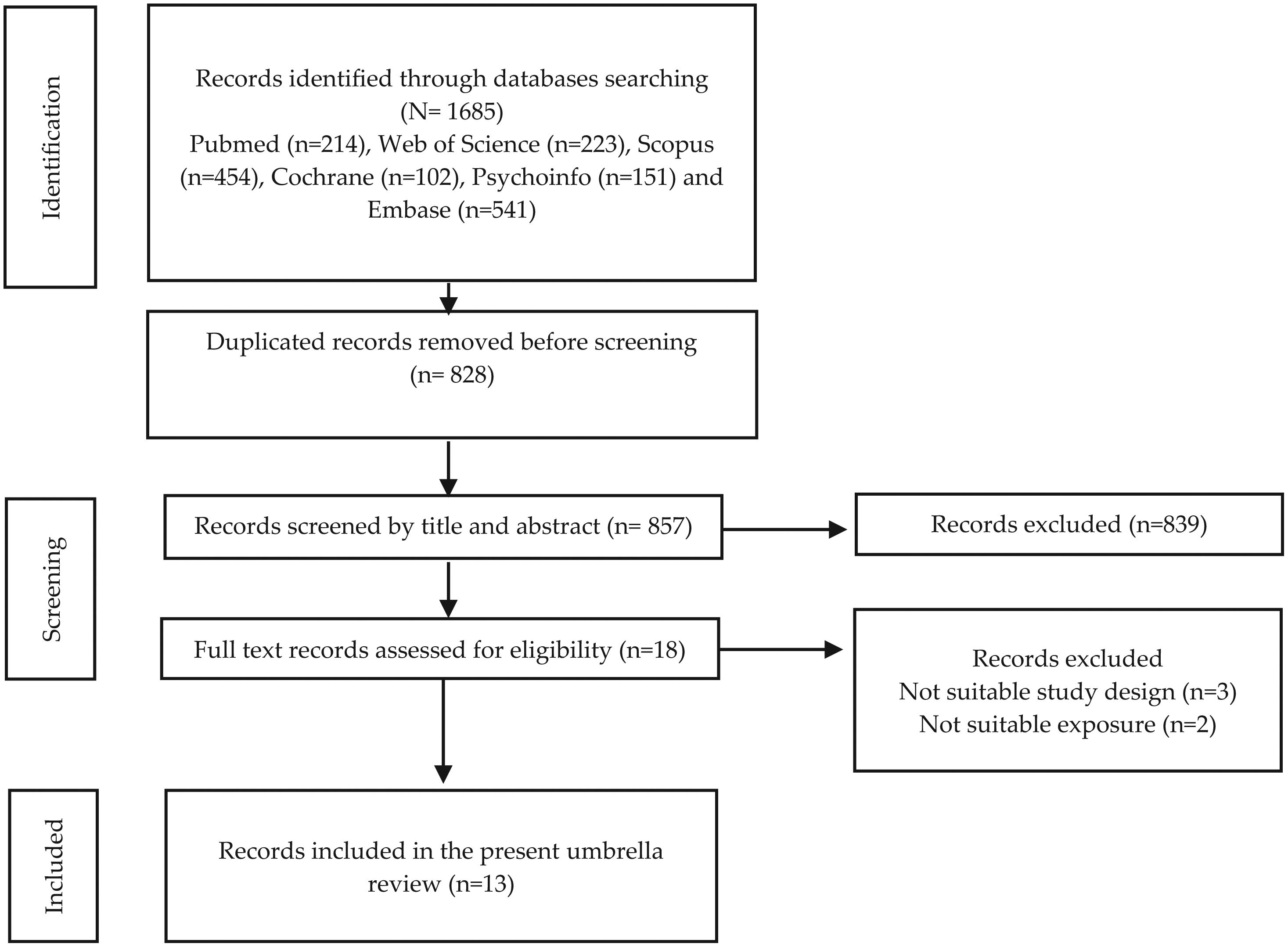

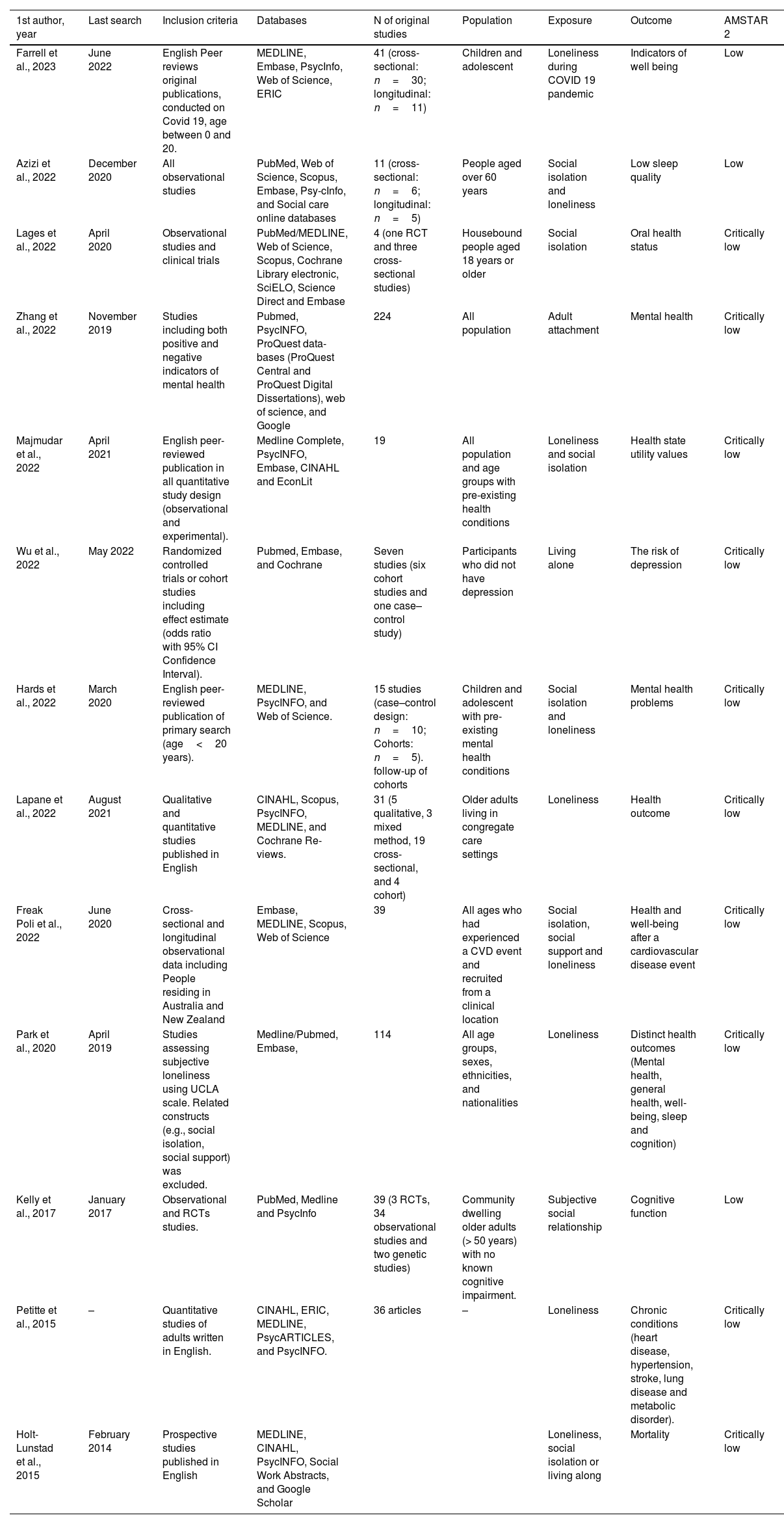

ResultsThe search yielded total of 1684 records and duplicates were eliminated (n=828). A first screening was conducted by title and abstract and full text of potential eligible records were assessed. Then, a total of five records was excluded as three did not meet study design criteria14–16 and two do not measure the suitable exposure.17,18 Finally, 13 systematic reviews were selected for data extraction and synthesis (Fig. 1). Four included meta-analysis.19–22 The exposure was measured under different aspects. Loneliness was explored in four systematic reviews as a single concept.21,23–25 Five systematic reviews analyze loneliness together with social isolation. Moreover, others similar instruct was analyzed (adult attachment, living alone and social relationship). Different instruments were considered for the exposure measurement except in the review of Park et al., that include only studies using the UCLA scale.21 The association between loneliness and similar constructs was frequently correlated with well-being, cardiovascular disease and cognition. However, only two systematic reviews analyzed for the outcome mortality22 and one oral health outcome.26 The characteristics of included systematic reviews are provided in Table 1.

Systematic reviews characteristics.

| 1st author, year | Last search | Inclusion criteria | Databases | N of original studies | Population | Exposure | Outcome | AMSTAR 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farrell et al., 2023 | June 2022 | English Peer reviews original publications, conducted on Covid 19, age between 0 and 20. | MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo, Web of Science, ERIC | 41 (cross-sectional: n=30; longitudinal: n=11) | Children and adolescent | Loneliness during COVID 19 pandemic | Indicators of well being | Low |

| Azizi et al., 2022 | December 2020 | All observational studies | PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, Psy-cInfo, and Social care online databases | 11 (cross-sectional: n=6; longitudinal: n=5) | People aged over 60 years | Social isolation and loneliness | Low sleep quality | Low |

| Lages et al., 2022 | April 2020 | Observational studies and clinical trials | PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library electronic, SciELO, Science Direct and Embase | 4 (one RCT and three cross-sectional studies) | Housebound people aged 18 years or older | Social isolation | Oral health status | Critically low |

| Zhang et al., 2022 | November 2019 | Studies including both positive and negative indicators of mental health | Pubmed, PsycINFO, ProQuest data- bases (ProQuest Central and ProQuest Digital Dissertations), web of science, and Google | 224 | All population | Adult attachment | Mental health | Critically low |

| Majmudar et al., 2022 | April 2021 | English peer-reviewed publication in all quantitative study design (observational and experimental). | Medline Complete, PsycINFO, Embase, CINAHL and EconLit | 19 | All population and age groups with pre-existing health conditions | Loneliness and social isolation | Health state utility values | Critically low |

| Wu et al., 2022 | May 2022 | Randomized controlled trials or cohort studies including effect estimate (odds ratio with 95% CI Confidence Interval). | Pubmed, Embase, and Cochrane | Seven studies (six cohort studies and one case–control study) | Participants who did not have depression | Living alone | The risk of depression | Critically low |

| Hards et al., 2022 | March 2020 | English peer-reviewed publication of primary search (age<20 years). | MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. | 15 studies (case–control design: n=10; Cohorts: n=5). follow-up of cohorts | Children and adolescent with pre-existing mental health conditions | Social isolation and loneliness | Mental health problems | Critically low |

| Lapane et al., 2022 | August 2021 | Qualitative and quantitative studies published in English | CINAHL, Scopus, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and Cochrane Re- views. | 31 (5 qualitative, 3 mixed method, 19 cross-sectional, and 4 cohort) | Older adults living in congregate care settings | Loneliness | Health outcome | Critically low |

| Freak Poli et al., 2022 | June 2020 | Cross-sectional and longitudinal observational data including People residing in Australia and New Zealand | Embase, MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science | 39 | All ages who had experienced a CVD event and recruited from a clinical location | Social isolation, social support and loneliness | Health and well-being after a cardiovascular disease event | Critically low |

| Park et al., 2020 | April 2019 | Studies assessing subjective loneliness using UCLA scale. Related constructs (e.g., social isolation, social support) was excluded. | Medline/Pubmed, Embase, | 114 | All age groups, sexes, ethnicities, and nationalities | Loneliness | Distinct health outcomes (Mental health, general health, well-being, sleep and cognition) | Critically low |

| Kelly et al., 2017 | January 2017 | Observational and RCTs studies. | PubMed, Medline and PsycInfo | 39 (3 RCTs, 34 observational studies and two genetic studies) | Community dwelling older adults (> 50 years) with no known cognitive impairment. | Subjective social relationship | Cognitive function | Low |

| Petitte et al., 2015 | – | Quantitative studies of adults written in English. | CINAHL, ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES, and PsycINFO. | 36 articles | – | Loneliness | Chronic conditions (heart disease, hypertension, stroke, lung disease and metabolic disorder). | Critically low |

| Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015 | February 2014 | Prospective studies published in English | MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Social Work Abstracts, and Google Scholar | Loneliness, social isolation or living along | Mortality | Critically low |

Based on the quality assessment tool AMSTAR-2,13 most of the included systematic reviews show a critically low (76.92%, n=10) and low quality (23.08%, n=3). Weaknesses in systematic reviews were meanly related to the following: item 7, excluded studies not listed and justified in 84.61% (n=11); item 10, the financial support of included studies not reported in 84.61% (n=11); and item 13, bias risk not considered or interpreted in 53.85% (n=7). Results related to each domain are shown in Fig. 2.

Association of loneliness with adverse health outcomesMental health and well beingLoneliness and similar constructs were associated to negative mental health in four studies.19,21,23,27 Poor well-being, the risk of anxiety, depression and suicidality was highly affected by loneliness.21 In individuals living alone the risk of depression increase by 42%.20 During the pandemic period of COVID-19, the level of well-being was low in children and adolescent with high level of loneliness. This situation increases the severity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescent with pre-existing mental health.23,28 Loneliness was also associated with depression in older persons living in congregate. However, few studies relate it to suicidal ideation.24 Others related constructs such adult's attachment was also positively associated to mental health such as depression and anxiety.19 Inversely, mental health can be improved by a great social health.27

Physical healthPhysical health outcomes analyzed was heterogenous. Only one systematic review analyzes the association between loneliness level and oral health. Evidence was not strong to suggest a possible association.26 No effect was observed on health state utility value.29 Other constructs such living status and partner status do not seem to affect physical and mental health.27 Contrary, the review of Petitte et al., suggests a possible association between loneliness and similar constructs with physical health outcomes especially chronic conditions such as heart diseases, diabetes and obesity.25 On the other hand, social relationships were associated with better cognitive functions in elderly people.30 The quality of sleep was also affected by social isolation and loneliness in older adults.31

MortalityThe number of systematic reviews analyzing mortality outcome was very limited (n=2). Social isolation, loneliness and living alone would increase this risk of mortality by 29%, 26%, and 32% respectively.22 However, results related to specific population such elderly people living in congregate care settings was mixed and no clear association was identified.24

DiscussionAvailable scientific evidence stressed the role of loneliness and similar constructs in increasing the risk of several health outcomes such as chronic diseases, negative mental health and well-being. The association of loneliness was most important in mental health and moderately so in other health outcomes such as well-being, physical health and sleep.21 The magnitude of association can be different according to the population characteristic. For example, cognition was more likely to be affected by loneliness in men.21 Regarding mortality and oral health, evidence was limited and the association was not clear. The magnitude of association may vary depending on study design (cross-sectional or longitudinal). Other factors should be considered in interpretation such as the health condition before the outcome occurrence and the presence of associated risk factors.

Only one study considered difference between objective and subjective social isolation and loneliness.31 Social health can be assessed under different aspects such as social isolation, social support and loneliness. Partner status and living status does not seem to reflect social isolation and social support in cardiac patients.27 Therefore, it may not adequately the association with health outcomes. Our fundings can be limited by the low number and quality of systematic reviews retrieved for each outcome. The available systematic reviews were carried out on different populations, so it was not always possible to compare the results with each other in the best way. Moreover, different methods were used for the exposure measurement. In this umbrella, the overlapping of evidence between reviews was not estimated as the number of systematic reviews including the same loneliness construct and health outcome was very limited. Strengths of this umbrella lie in the interest in an under-researched topic, and we demonstrate that it has a major impact on the health status. Moreover, this umbrella is reported according to PRIOR checklist12 and use an exhaustive search equation including six databases.

ConclusionMost constructs of loneliness seem to be related to mental and physical conditions. Although the evidence was not sufficient to confirm causal association, a preventive strategy must be recommended, especially for vulnerable populations.

Ethical considerationsThis study was considered exempt from ethical review as it was a literature review of previously published studies.

FundingNo specific funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestNone to declare.

K.S.K. is a distinguished researcher at the University of Granada funded by the Beatriz Galindo program (senior modality) of the Spanish Ministry of Education; M.N.-N. has a research contract from the Carlos III research institute group (Juan Rodés JR23/00025).