To determine the prevalence of and risk factors for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-PE) faecal carriage among healthy volunteers from Barcelona, and to estimate the pooled prevalence in the community in Spain.

MethodsUniversity students were asked to complete a questionnaire and provide a rectal swab, which was tested for ESBL-producing, ciprofloxacin- and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole-resistant Enterobacterales. Risk factors for carriage of antimicrobial resistance were identified by multivariate logistic regression. To place these results in the appropriate context, a systematic literature search was conducted to retrieve articles containing data on the prevalence of ESBL-PE faecal carriage in the community in Spain. To obtain the pooled prevalence, a random-effects meta-analysis was performed.

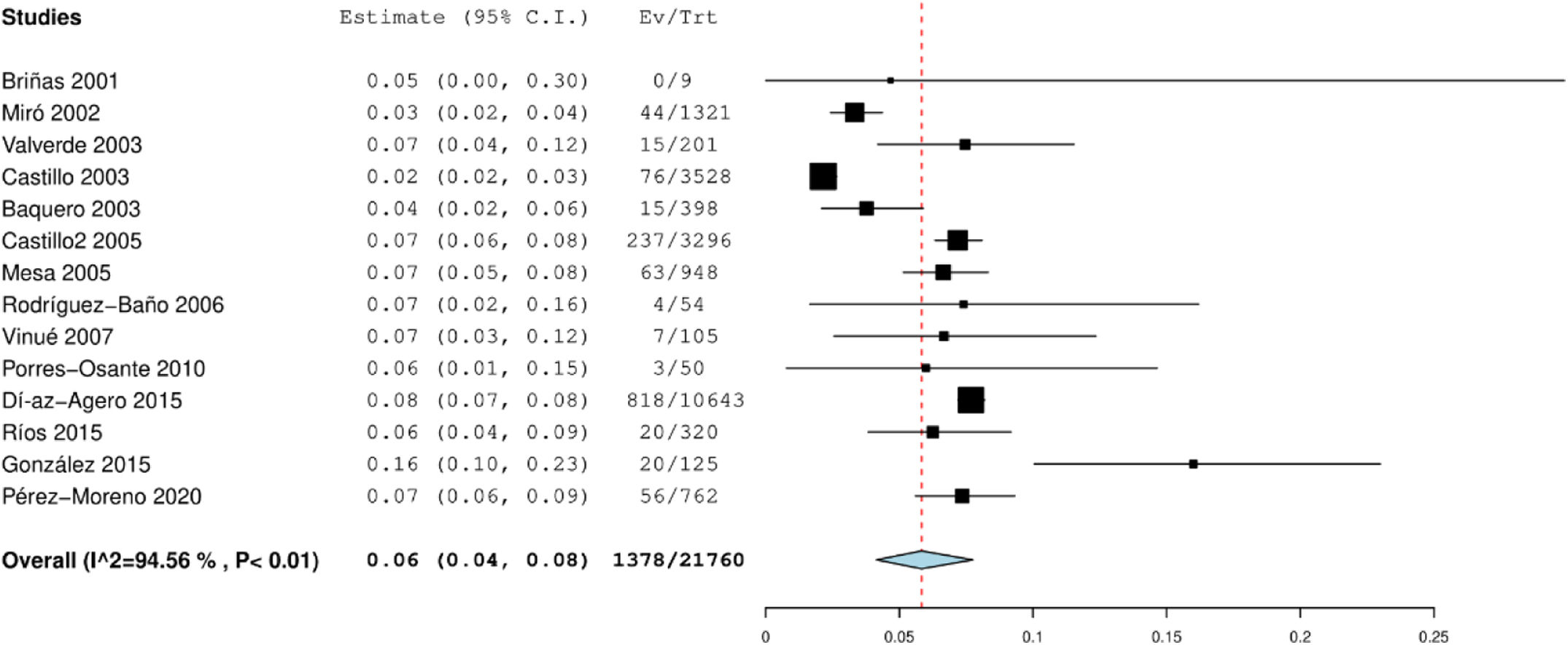

ResultsOne hundred and thirty-five of 214 participants were included in the analysis. Faecal carriage of Escherichia coli/Klebsiella pneumoniae (E/K) resistant to at least one of the antibiotics tested was found in 32 participants (23.7%). Fourteen subjects carried ESBL-E/K (10.4%), with the CTX-M type being the most prevalent (85.7%). Risk factors for ESBL carriage were travel to a high-risk region in the past 3 years (OR 5.66; 95% CI 1.07–29.9) and living in a crowded city district (OR 6.91; 95% CI 1.22–39.08). Thirteen articles covering 21,760 individuals from Spain were included in the meta-analysis, giving a pooled prevalence rate for ESBL-PE carriage in the community of 5.8% (95% CI 4.1–7.8%), and a steady increase per year.

ConclusionsThe faecal colonisation prevalence by ESBL-PE among healthy individuals in Spain is high. It is associated with international travel and living in crowded city districts.

Determinar la prevalencia y los factores de riesgo de la colonización fecal por ESBL-PE entre voluntarios sanos de Barcelona, así como estimar la prevalencia en la comunidad en España.

MétodosEstudiantes universitarios completaron un cuestionario y proporcionaron un frotis rectal, que fue analizado para detectar Enterobacterales productores de betalactamasas de espectro extendido (BLEE-PE) y resistentes a ciprofloxacino y a trimetoprima-sulfametoxazol. Los factores de riesgo se identificaron mediante regresión logística multivariada. Para situar estos resultados en el contexto adecuado, se realizó una búsqueda sistemática de la literatura para recuperar artículos con datos sobre la prevalencia de la colonización fecal por BLEE-PE en la comunidad en España. Para obtener la prevalencia combinada, se realizó un metaanálisis de efectos aleatorios.

ResultadosCiento treinta y cinco de los 214 participantes fueron incluidos en el análisis. Se encontró colonización fecal de E. coli/K. pneumoniae (E/K) resistente a al menos uno de los antibióticos analizados en 32 participantes (23,7%). Catorce sujetos portaban BLEE-E/K (10,4%), siendo el tipo CTX-M el más prevalente (85,7%). Los factores de riesgo para la colonización por BLEE fueron viajar a una región de alto riesgo en los últimos 3 años (OR: 5,66; IC 95%: 1,07-29,9) y vivir en un distrito urbano densamente poblado (OR: 6,91; IC 95%: 1,22-39,08). En el metaanálisis se incluyeron 13 artículos que abarcaban a 21.760 individuos de España, resultando una tasa de prevalencia combinada de colonización por BLEE-PE en la comunidad del 5,8% (IC 95%: 4,1-7,8%), con un con un aumento anual constante.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de la colonización fecal por BLEE-PE entre individuos sanos en España es alta. Está asociada con viajes internacionales y vivir en distritos urbanos densamente poblados.

Antibiotic resistance in community-acquired infections is becoming a major public health threat.1 In this context, Enterobacterales, mainly those producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL), are a major concern: patients often require carbapenems and treatment options are limited.2

Genes conferring ESBL activity are easily transmitted and thus disseminated.3 Furthermore, plasmids carrying ESBLs often encode other antibiotic resistance genes such as plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants or sulphonamide resistance genes, conferring on ESBL-producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-PE) a much broader spectrum of resistance.

ESBL-PE faecal carriage rates in the community are increasing worldwide.1,3,4 And while the presence of this gut microbiota reservoir is usually asymptomatic, many studies have shown a worse outcome in patients with ESBL-PE infections.5

In Europe, the reported community carriage prevalence is 6% (data from studies conducted between 2004 and 2019).1,4 In Spain, a few studies have assessed ESBL-PE carriage rates in the community,6–8 but a pooled prevalence has not been reported.

Hypothesised attributable sources of human exposure to ESBLs include animals, food, the environment, and other human beings.9,10 However, it remains unclear which transmission route or risk factor for acquisition antibiotic-resistant bacteria predominates.

The aim of the present study was to estimate the prevalence of faecal carriage of ESBL-producing, ciprofloxacin-(CIP) and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (SXT)-resistant Enterobacterales in healthy volunteers from Barcelona, Spain, and to assess the risk factors associated with colonisation status. To place these results in the appropriate geographical and temporal context, a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis of published community carriage rates in Spain was undertaken.

MethodsThis study was reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cross-sectional studies and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 checklist.

Participant data collectionA total of around 240 healthy first- and second-year medical students living in Barcelona or surrounding areas were invited to participate by direct face-to-face recruitment between January 2020 and September 2020. After providing informed consent, participants received material to self-collect a rectal swab with the indications of inserting it about 3–5cm into the anal canal and rubbing it gently for about 5–10s against the walls of the rectum. Participants were also asked to fill in a detailed questionnaire about possible risk factors for acquiring drug-resistant bacteria (demographics, use of medication, contact with animals, diet, hygiene, and travel history). Regions where >25% of Escherichia coli clinical isolates are estimated to be ESBL producers9 were defined as high-risk regions.

MicrobiologyRectal swabs were taken using Deltalab Amies agar gel transport swabs and streaked on chromID™ ESBL, CARBA/OXA and MacConkey agar plates (bioMérieux, France). A first reading was taken after 24h and a second one after 48h of incubation at 37°C. These selective and differential media were used for presumptive identification of E. coli (pink colonies) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (green colonies). On MacConkey agar, both colonies are lactose-positive and the difference is established by the consistency of bacterial isolates: dry (E. coli) and mucous (K. pneumoniae). Definitive bacterial identification was performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight (MALDI–TOF) mass spectrometry.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by the disc diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar plates, including a synergy test to detect/confirm ESBL production and paper disks impregnated with ciprofloxacin and SXT to detect resistance to these antibiotics. Results were interpreted following European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) clinical breakpoints (Version 9.0).11

The ESBL-producing isolates were subjected to nucleotide sequencing to determine their molecular type. DNA extraction was performed using DNeasy Ultra Clean Microbial kit (Qiagen) as described by manufacturer. Genome DNA was quantified using Qubit 3.0 (Thermofisher). Library preparation and Whole Genome Sequencing were performed by NovoGene (Novogene Sequencing Europe) on an Illumina NovaSeq instrument with Illumina 2×150 cycles sequencing. Reads were quality trimmed using fastp v0.23.2 (available at: https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp); trimmed reads were de novo assembled using Unicycler v0.5.0, with Spades v3.15.5 (available at: https://github.com/rrwick/Unicycler/releases and https://github.com/ablab/spades, respectively). Fasta files were then submitted to ResFinder and CARD to betalactamse resistance prediction. Sequence types (ST) were determined using two schemes for E. coli (Achtman and Pasteur MLST) and one scheme for K. pneumoniae (Pasteur MLST).

Metanalysis data sources and search termsA systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed to retrieve relevant articles published between 1 January 2000 and 23 December 2020. Five groups of search terms were used: (i) Escherichia coli OR E. coli OR Enterobacterales; (ii) extended-spectrum beta-lactamase OR ESBL; (iii) faecal OR faeces OR stool OR intestinal OR gastrointestinal tract; and (iv) community OR community-acquired OR healthy OR volunteers OR at admission; (v) Spain OR Barcelona OR Madrid. These groups were then connected by the Boolean operator ‘AND’ to find papers that contained these terms anywhere in the article.

Statistical analysesFor descriptive statistics, quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies (number and percentage). To check the association of continuous and categorical variables with ESBL-producing, CIP- and SXT-resistant Enterobacterales carriage, the Student's t-test and Chi-squared test (or Fisher's exact in the case of expected numbers<5) were performed, as appropriate. Logistic regression was used to study the risk factors associated with the carriage of antibiotic-resistant E. coli or K. pneumoniae. Four logistic regression models were developed (one for each type of resistance (ESBL-producing or resistance to CIP or SXT) and an additional one combining the three resistance types assessed). All variables with a p value<0.05 in univariate analysis, as well as other variables considered clinically relevant (age, place of residence, travel history and meat consumption) were included in multivariate models. Results are presented as odd ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). A p value<0.05 was used to determine significance. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.

The meta-analysis was performed using a random-effects method to obtain a pooled prevalence and estimate the national trend of faecal ESBL-PE carriage. The Freeman-Tukey arcsine methodology was used to stabilise the variance of raw proportions, and no studies with 0% or 100% proportions were excluded. The I2 statistic was used to test heterogeneity. Following this meta-analysis, we performed a univariate meta-regression taking the year of publication as predictor variable. Results from this meta-regression were expressed by means of β (coefficient of year) and plotting a bubble plot (prevalence by year).

EthicsThis study was approved by the Parc de Salut Mar-IMIM ethics committee in Barcelona (no. 2019/8971/I). All participants provided written informed consent. The present study was carried out in accordance with current regulations and the basic principles of the protection of the rights and dignity of the human being, as stated in the Helsinki Declaration (64th General Assembly, Brazil, October 2013).

ResultsObservational studyA total of 214 participants were enrolled in the study, 135 of which were included in the analysis (Fig. S1). Seventy-nine participants were excluded, either because they did not respond to the questionnaire (n=1), or their rectal swabs were lost (n=46) or not well taken (defined as non-bacterial growth in MacConkey agar plates after 48h of incubation at 37°C) (n=30), or the samples were well taken but neither E. coli nor K. pneumoniae were identified on MacConkey agar plates (n=2). Comparison of baseline characteristics of participants not included in the analysis because of not well taken swab samples and those finally included is shown in Table S1.

Faecal carriage of E. coli/K. pneumoniae (E/K) with at least one of the phenotypes of interest (ESBL-producing or resistance to CIP or SXT) was found in 32 participants (23.7±7.17%, 95% CI): 14 subjects carried ESBL-E/K (10.4±5.14%, 95% CI), 20 carried co-trimoxazole (SXT)-resistant E/K (14.8±5.99%, 95% CI) and 14 carried ciprofloxacin (CIP)-resistant E/K (10.4±5.14%, 95% CI). CIP and/or SXT co-resistance in ESBL-E/K was found in 9 out of 14 (64.3%) of the ESBL-E/K identified.

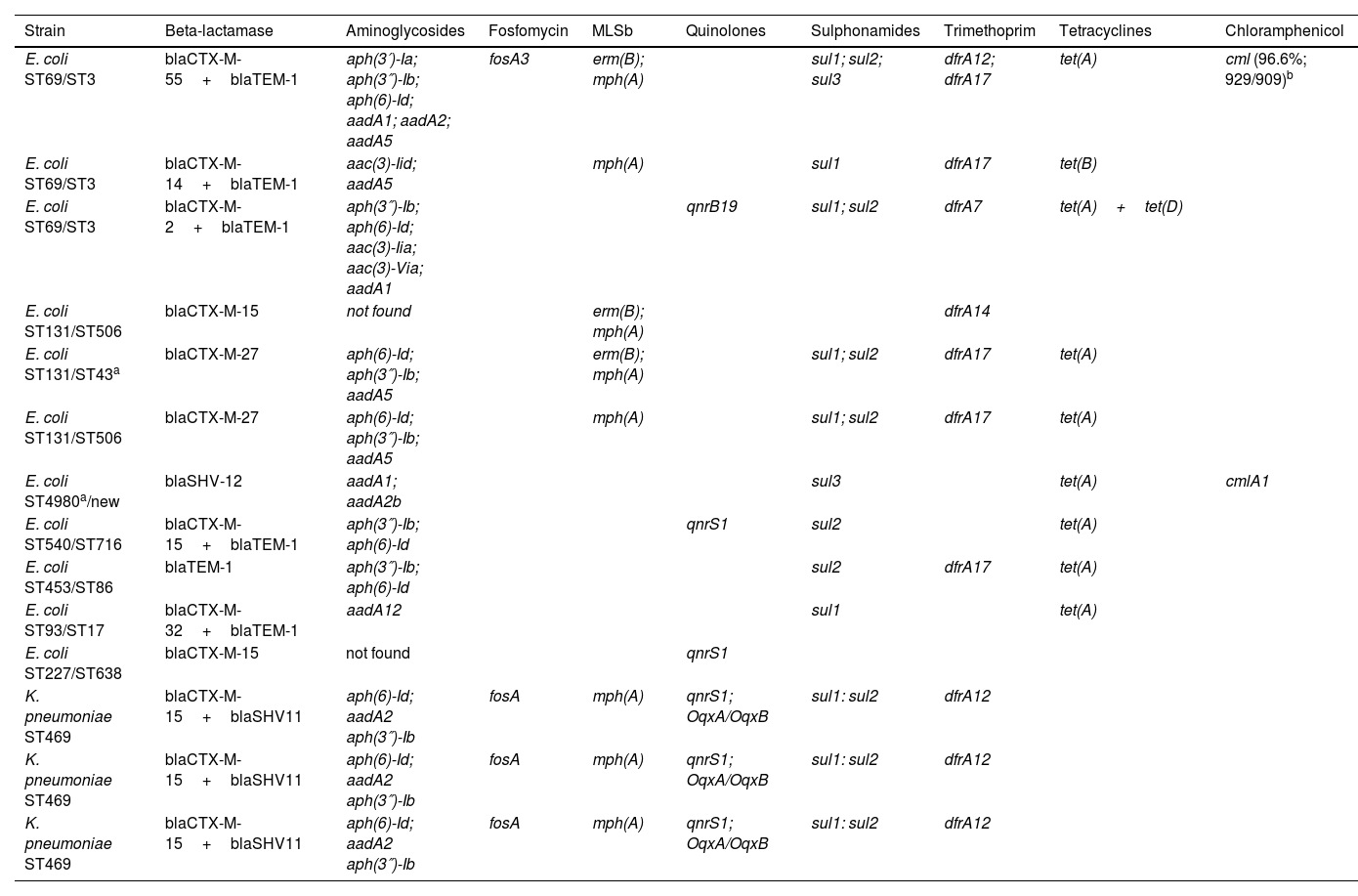

The genotypic characterisation of the 14 ESBL-E/K producers isolated is shown in Table 1. Eleven out of 14 (78.5%) isolates were E. coli and three out of 14 (21.4%) were K. pneumoniae. Multidrug resistance (resistance to at least three antibiotic families) was observed in 92.8% of the ESBL-producing strains. Ten out of 14 (71.4%) isolates had more than one type of beta-lactamase. The CTX-M-type was the most prevalent (85.7%) followed by the TEM-type (42.9%) and the SHV-type (28.5%). Discrepancies between phenotypic and genotypic ESBL confirmation tests were only seen with E. coli isolate ST453, as TEM-1 beta-lactamase is not considered an ESBL; a false positive result probably explained by TEM-1 hyperproduction combined with altered permeability, a mechanism argued in EUCAST guidelines. All the K. pneumoniae isolates belonged to the same sequence type: ST469. E. coli isolates belonged to different sequence types: ST69, ST131, ST540, ST453, ST93 and ST227.

Sequence type (ST) and resistome of 14 ESBL-E. coli/K. pneumoniae strains isolated.

| Strain | Beta-lactamase | Aminoglycosides | Fosfomycin | MLSb | Quinolones | Sulphonamides | Trimethoprim | Tetracyclines | Chloramphenicol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli ST69/ST3 | blaCTX-M-55+blaTEM-1 | aph(3′)-Ia; aph(3″)-Ib; aph(6)-Id; aadA1; aadA2; aadA5 | fosA3 | erm(B); mph(A) | sul1; sul2; sul3 | dfrA12; dfrA17 | tet(A) | cml (96.6%; 929/909)b | |

| E. coli ST69/ST3 | blaCTX-M-14+blaTEM-1 | aac(3)-Iid; aadA5 | mph(A) | sul1 | dfrA17 | tet(B) | |||

| E. coli ST69/ST3 | blaCTX-M-2+blaTEM-1 | aph(3″)-Ib; aph(6)-Id; aac(3)-Iia; aac(3)-Via; aadA1 | qnrB19 | sul1; sul2 | dfrA7 | tet(A)+tet(D) | |||

| E. coli ST131/ST506 | blaCTX-M-15 | not found | erm(B); mph(A) | dfrA14 | |||||

| E. coli ST131/ST43a | blaCTX-M-27 | aph(6)-Id; aph(3″)-Ib; aadA5 | erm(B); mph(A) | sul1; sul2 | dfrA17 | tet(A) | |||

| E. coli ST131/ST506 | blaCTX-M-27 | aph(6)-Id; aph(3″)-Ib; aadA5 | mph(A) | sul1; sul2 | dfrA17 | tet(A) | |||

| E. coli ST4980a/new | blaSHV-12 | aadA1; aadA2b | sul3 | tet(A) | cmlA1 | ||||

| E. coli ST540/ST716 | blaCTX-M-15+blaTEM-1 | aph(3″)-Ib; aph(6)-Id | qnrS1 | sul2 | tet(A) | ||||

| E. coli ST453/ST86 | blaTEM-1 | aph(3″)-Ib; aph(6)-Id | sul2 | dfrA17 | tet(A) | ||||

| E. coli ST93/ST17 | blaCTX-M-32+blaTEM-1 | aadA12 | sul1 | tet(A) | |||||

| E. coli ST227/ST638 | blaCTX-M-15 | not found | qnrS1 | ||||||

| K. pneumoniae ST469 | blaCTX-M-15+blaSHV11 | aph(6)-Id; aadA2 aph(3″)-Ib | fosA | mph(A) | qnrS1; OqxA/OqxB | sul1: sul2 | dfrA12 | ||

| K. pneumoniae ST469 | blaCTX-M-15+blaSHV11 | aph(6)-Id; aadA2 aph(3″)-Ib | fosA | mph(A) | qnrS1; OqxA/OqxB | sul1: sul2 | dfrA12 | ||

| K. pneumoniae ST469 | blaCTX-M-15+blaSHV11 | aph(6)-Id; aadA2 aph(3″)-Ib | fosA | mph(A) | qnrS1; OqxA/OqxB | sul1: sul2 | dfrA12 |

To determine the ST for E. coli, two schemes were used: MLST Achtman which includes loci adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, recA, and MLST Pasteur which includes loci dinB, icdA, pabB, polB, putP, trpA, trpB, uidA.

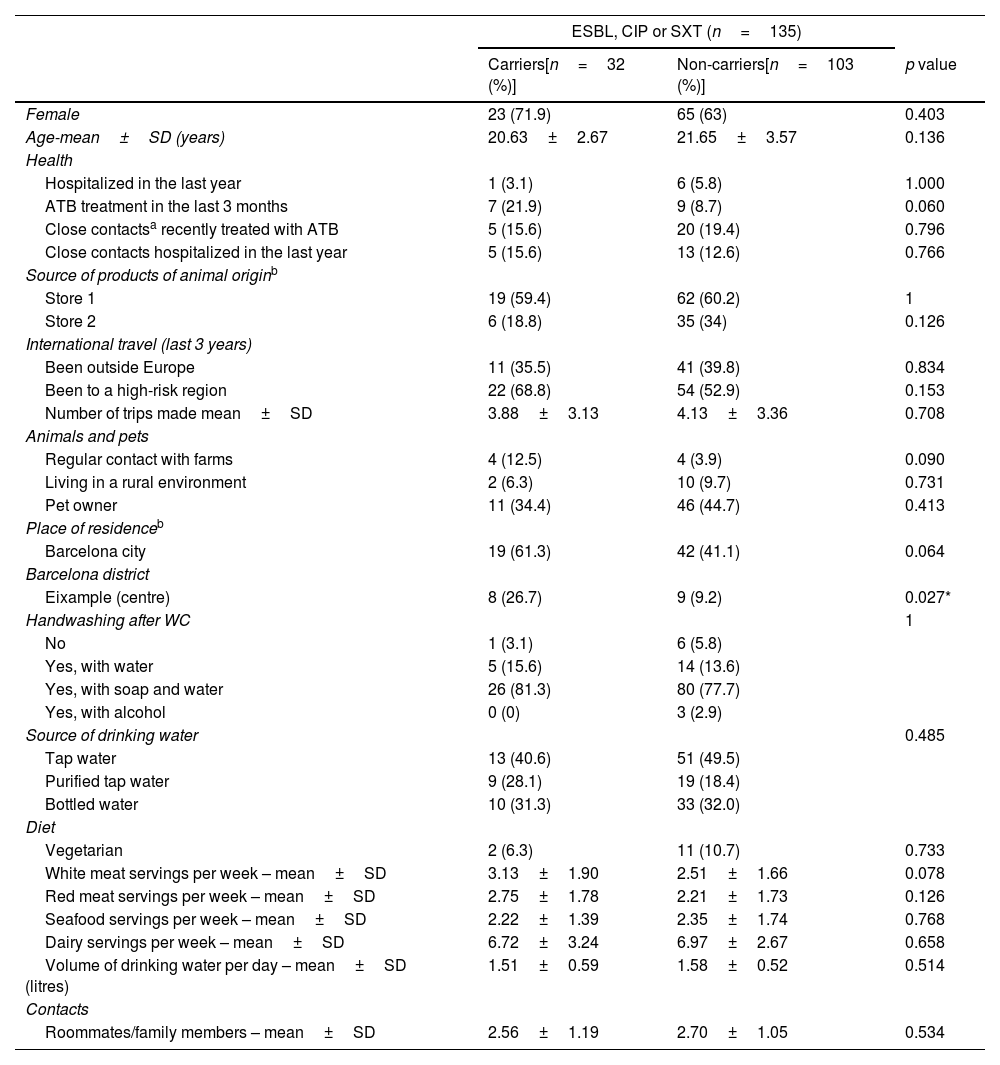

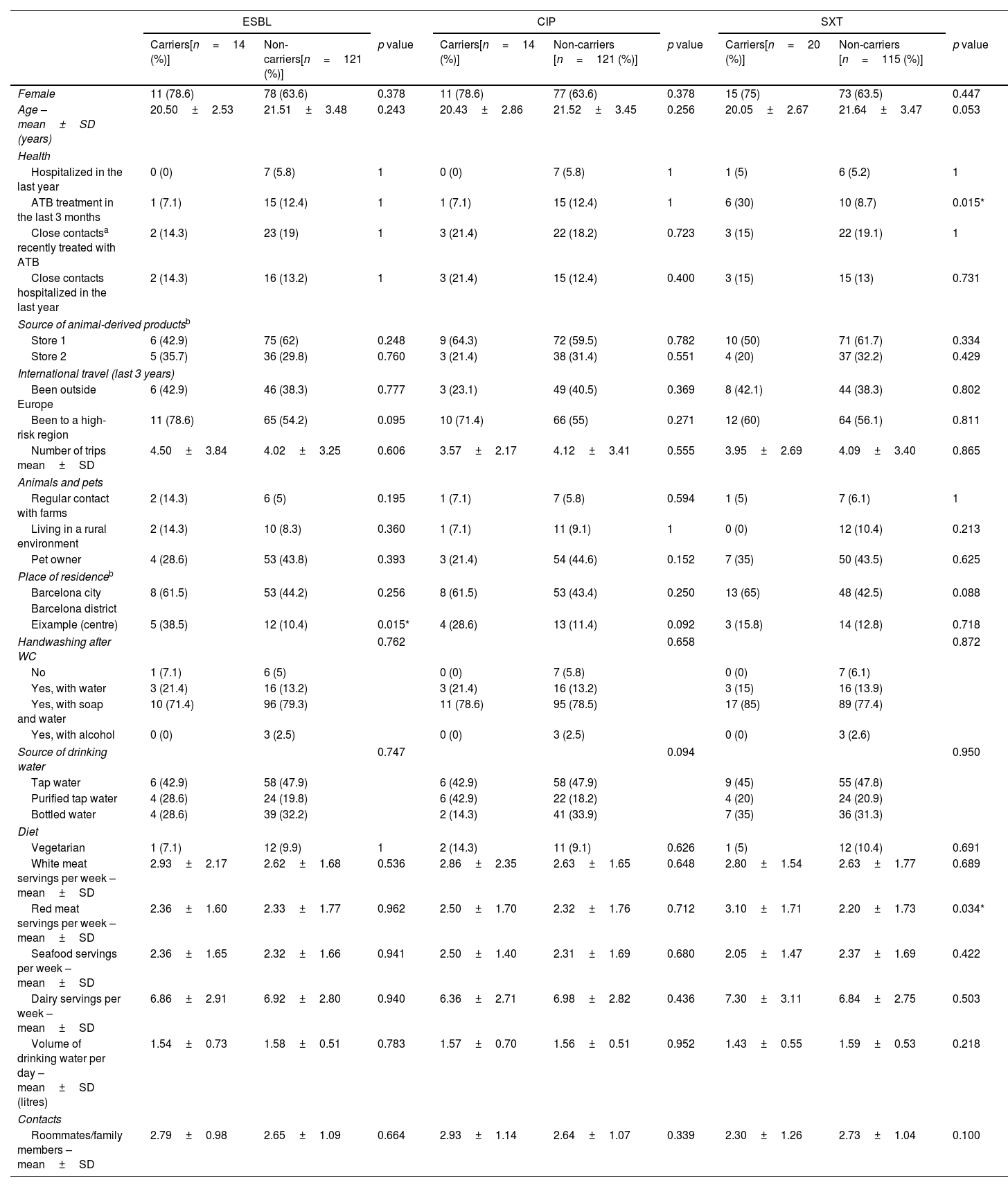

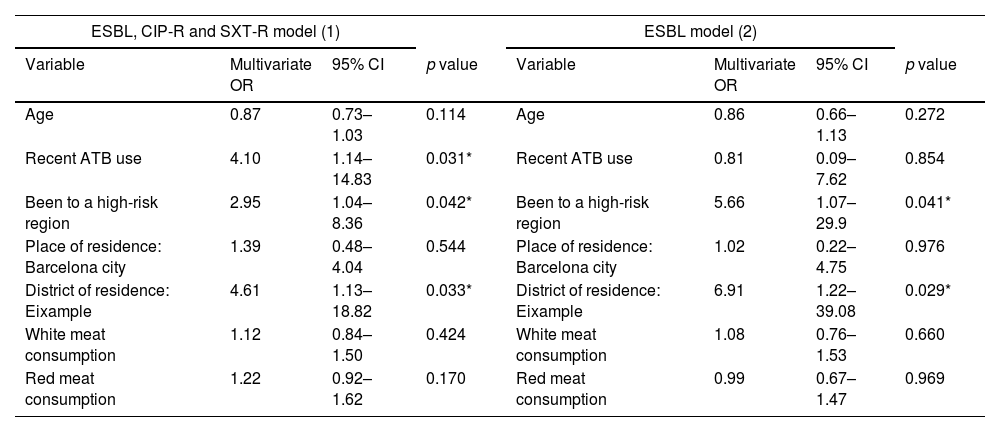

The characteristics of the participants are presented in Tables 2a and 2b. Table 3 shows the multivariate analysis of potential risk factors for the carriage of antibiotic-resistant E/K. Antibiotic therapy in the previous 3 months (OR 4.10; 95% CI 1.14–14.83), travel to a high-risk region in the past 3 years (OR 2.95; 95% CI 1.04–8.36) and living in Eixample (a crowded district in the Barcelona centre) (OR 4.61; 95% CI 1.13–18.82) were found to be independently associated with carriage of Enterobacterales resistant to any of the three antimicrobials assessed.

Descriptive characteristics of faecal carriers of the ESBL-producing or CIP or SXT resistant bacteria vs non-carriers.

| ESBL, CIP or SXT (n=135) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carriers[n=32 (%)] | Non-carriers[n=103 (%)] | p value | |

| Female | 23 (71.9) | 65 (63) | 0.403 |

| Age-mean±SD (years) | 20.63±2.67 | 21.65±3.57 | 0.136 |

| Health | |||

| Hospitalized in the last year | 1 (3.1) | 6 (5.8) | 1.000 |

| ATB treatment in the last 3 months | 7 (21.9) | 9 (8.7) | 0.060 |

| Close contactsa recently treated with ATB | 5 (15.6) | 20 (19.4) | 0.796 |

| Close contacts hospitalized in the last year | 5 (15.6) | 13 (12.6) | 0.766 |

| Source of products of animal originb | |||

| Store 1 | 19 (59.4) | 62 (60.2) | 1 |

| Store 2 | 6 (18.8) | 35 (34) | 0.126 |

| International travel (last 3 years) | |||

| Been outside Europe | 11 (35.5) | 41 (39.8) | 0.834 |

| Been to a high-risk region | 22 (68.8) | 54 (52.9) | 0.153 |

| Number of trips made mean±SD | 3.88±3.13 | 4.13±3.36 | 0.708 |

| Animals and pets | |||

| Regular contact with farms | 4 (12.5) | 4 (3.9) | 0.090 |

| Living in a rural environment | 2 (6.3) | 10 (9.7) | 0.731 |

| Pet owner | 11 (34.4) | 46 (44.7) | 0.413 |

| Place of residenceb | |||

| Barcelona city | 19 (61.3) | 42 (41.1) | 0.064 |

| Barcelona district | |||

| Eixample (centre) | 8 (26.7) | 9 (9.2) | 0.027* |

| Handwashing after WC | 1 | ||

| No | 1 (3.1) | 6 (5.8) | |

| Yes, with water | 5 (15.6) | 14 (13.6) | |

| Yes, with soap and water | 26 (81.3) | 80 (77.7) | |

| Yes, with alcohol | 0 (0) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Source of drinking water | 0.485 | ||

| Tap water | 13 (40.6) | 51 (49.5) | |

| Purified tap water | 9 (28.1) | 19 (18.4) | |

| Bottled water | 10 (31.3) | 33 (32.0) | |

| Diet | |||

| Vegetarian | 2 (6.3) | 11 (10.7) | 0.733 |

| White meat servings per week – mean±SD | 3.13±1.90 | 2.51±1.66 | 0.078 |

| Red meat servings per week – mean±SD | 2.75±1.78 | 2.21±1.73 | 0.126 |

| Seafood servings per week – mean±SD | 2.22±1.39 | 2.35±1.74 | 0.768 |

| Dairy servings per week – mean±SD | 6.72±3.24 | 6.97±2.67 | 0.658 |

| Volume of drinking water per day – mean±SD (litres) | 1.51±0.59 | 1.58±0.52 | 0.514 |

| Contacts | |||

| Roommates/family members – mean±SD | 2.56±1.19 | 2.70±1.05 | 0.534 |

CIP: ciprofloxacin. SXT: co-trimoxazole. ATB: antibiotic.

Additional variables on the source of animal-derived products and place of residence can be found in supplementary information (Table S3).

Descriptive characteristics of faecal carriers of each type of resistance (ESBL-producing or resistance to CIP or SXT) vs non-carriers.

| ESBL | CIP | SXT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carriers[n=14 (%)] | Non-carriers[n=121 (%)] | p value | Carriers[n=14 (%)] | Non-carriers [n=121 (%)] | p value | Carriers[n=20 (%)] | Non-carriers [n=115 (%)] | p value | |

| Female | 11 (78.6) | 78 (63.6) | 0.378 | 11 (78.6) | 77 (63.6) | 0.378 | 15 (75) | 73 (63.5) | 0.447 |

| Age – mean±SD (years) | 20.50±2.53 | 21.51±3.48 | 0.243 | 20.43±2.86 | 21.52±3.45 | 0.256 | 20.05±2.67 | 21.64±3.47 | 0.053 |

| Health | |||||||||

| Hospitalized in the last year | 0 (0) | 7 (5.8) | 1 | 0 (0) | 7 (5.8) | 1 | 1 (5) | 6 (5.2) | 1 |

| ATB treatment in the last 3 months | 1 (7.1) | 15 (12.4) | 1 | 1 (7.1) | 15 (12.4) | 1 | 6 (30) | 10 (8.7) | 0.015* |

| Close contactsa recently treated with ATB | 2 (14.3) | 23 (19) | 1 | 3 (21.4) | 22 (18.2) | 0.723 | 3 (15) | 22 (19.1) | 1 |

| Close contacts hospitalized in the last year | 2 (14.3) | 16 (13.2) | 1 | 3 (21.4) | 15 (12.4) | 0.400 | 3 (15) | 15 (13) | 0.731 |

| Source of animal-derived productsb | |||||||||

| Store 1 | 6 (42.9) | 75 (62) | 0.248 | 9 (64.3) | 72 (59.5) | 0.782 | 10 (50) | 71 (61.7) | 0.334 |

| Store 2 | 5 (35.7) | 36 (29.8) | 0.760 | 3 (21.4) | 38 (31.4) | 0.551 | 4 (20) | 37 (32.2) | 0.429 |

| International travel (last 3 years) | |||||||||

| Been outside Europe | 6 (42.9) | 46 (38.3) | 0.777 | 3 (23.1) | 49 (40.5) | 0.369 | 8 (42.1) | 44 (38.3) | 0.802 |

| Been to a high-risk region | 11 (78.6) | 65 (54.2) | 0.095 | 10 (71.4) | 66 (55) | 0.271 | 12 (60) | 64 (56.1) | 0.811 |

| Number of trips mean±SD | 4.50±3.84 | 4.02±3.25 | 0.606 | 3.57±2.17 | 4.12±3.41 | 0.555 | 3.95±2.69 | 4.09±3.40 | 0.865 |

| Animals and pets | |||||||||

| Regular contact with farms | 2 (14.3) | 6 (5) | 0.195 | 1 (7.1) | 7 (5.8) | 0.594 | 1 (5) | 7 (6.1) | 1 |

| Living in a rural environment | 2 (14.3) | 10 (8.3) | 0.360 | 1 (7.1) | 11 (9.1) | 1 | 0 (0) | 12 (10.4) | 0.213 |

| Pet owner | 4 (28.6) | 53 (43.8) | 0.393 | 3 (21.4) | 54 (44.6) | 0.152 | 7 (35) | 50 (43.5) | 0.625 |

| Place of residenceb | |||||||||

| Barcelona city | 8 (61.5) | 53 (44.2) | 0.256 | 8 (61.5) | 53 (43.4) | 0.250 | 13 (65) | 48 (42.5) | 0.088 |

| Barcelona district | |||||||||

| Eixample (centre) | 5 (38.5) | 12 (10.4) | 0.015* | 4 (28.6) | 13 (11.4) | 0.092 | 3 (15.8) | 14 (12.8) | 0.718 |

| Handwashing after WC | 0.762 | 0.658 | 0.872 | ||||||

| No | 1 (7.1) | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 7 (5.8) | 0 (0) | 7 (6.1) | |||

| Yes, with water | 3 (21.4) | 16 (13.2) | 3 (21.4) | 16 (13.2) | 3 (15) | 16 (13.9) | |||

| Yes, with soap and water | 10 (71.4) | 96 (79.3) | 11 (78.6) | 95 (78.5) | 17 (85) | 89 (77.4) | |||

| Yes, with alcohol | 0 (0) | 3 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.6) | |||

| Source of drinking water | 0.747 | 0.094 | 0.950 | ||||||

| Tap water | 6 (42.9) | 58 (47.9) | 6 (42.9) | 58 (47.9) | 9 (45) | 55 (47.8) | |||

| Purified tap water | 4 (28.6) | 24 (19.8) | 6 (42.9) | 22 (18.2) | 4 (20) | 24 (20.9) | |||

| Bottled water | 4 (28.6) | 39 (32.2) | 2 (14.3) | 41 (33.9) | 7 (35) | 36 (31.3) | |||

| Diet | |||||||||

| Vegetarian | 1 (7.1) | 12 (9.9) | 1 | 2 (14.3) | 11 (9.1) | 0.626 | 1 (5) | 12 (10.4) | 0.691 |

| White meat servings per week – mean±SD | 2.93±2.17 | 2.62±1.68 | 0.536 | 2.86±2.35 | 2.63±1.65 | 0.648 | 2.80±1.54 | 2.63±1.77 | 0.689 |

| Red meat servings per week – mean±SD | 2.36±1.60 | 2.33±1.77 | 0.962 | 2.50±1.70 | 2.32±1.76 | 0.712 | 3.10±1.71 | 2.20±1.73 | 0.034* |

| Seafood servings per week – mean±SD | 2.36±1.65 | 2.32±1.66 | 0.941 | 2.50±1.40 | 2.31±1.69 | 0.680 | 2.05±1.47 | 2.37±1.69 | 0.422 |

| Dairy servings per week – mean±SD | 6.86±2.91 | 6.92±2.80 | 0.940 | 6.36±2.71 | 6.98±2.82 | 0.436 | 7.30±3.11 | 6.84±2.75 | 0.503 |

| Volume of drinking water per day – mean±SD (litres) | 1.54±0.73 | 1.58±0.51 | 0.783 | 1.57±0.70 | 1.56±0.51 | 0.952 | 1.43±0.55 | 1.59±0.53 | 0.218 |

| Contacts | |||||||||

| Roommates/family members – mean±SD | 2.79±0.98 | 2.65±1.09 | 0.664 | 2.93±1.14 | 2.64±1.07 | 0.339 | 2.30±1.26 | 2.73±1.04 | 0.100 |

CIP: ciprofloxacin. SXT: co-trimoxazole. ATB: antibiotic.

Additional variables on the source of animal-derived products and place of residence can be found in supplementary information (Table S3).

Multivariate analysis models of risk factors for different antimicrobial resistance profiles.

| ESBL, CIP-R and SXT-R model (1) | ESBL model (2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Multivariate OR | 95% CI | p value | Variable | Multivariate OR | 95% CI | p value |

| Age | 0.87 | 0.73–1.03 | 0.114 | Age | 0.86 | 0.66–1.13 | 0.272 |

| Recent ATB use | 4.10 | 1.14–14.83 | 0.031* | Recent ATB use | 0.81 | 0.09–7.62 | 0.854 |

| Been to a high-risk region | 2.95 | 1.04–8.36 | 0.042* | Been to a high-risk region | 5.66 | 1.07–29.9 | 0.041* |

| Place of residence: Barcelona city | 1.39 | 0.48–4.04 | 0.544 | Place of residence: Barcelona city | 1.02 | 0.22–4.75 | 0.976 |

| District of residence: Eixample | 4.61 | 1.13–18.82 | 0.033* | District of residence: Eixample | 6.91 | 1.22–39.08 | 0.029* |

| White meat consumption | 1.12 | 0.84–1.50 | 0.424 | White meat consumption | 1.08 | 0.76–1.53 | 0.660 |

| Red meat consumption | 1.22 | 0.92–1.62 | 0.170 | Red meat consumption | 0.99 | 0.67–1.47 | 0.969 |

| CIP-R model (3) | SXT-R model (4) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Multivariate OR | 95% CI | p value | Variable | Multivariate OR | 95% CI | p value |

| Age | 0.89 | 0.71–1.11 | 0.293 | Age | 0.89 | 0.74–1.07 | 0.208 |

| Recent ATB use | 0.45 | 0.05–3.89 | 0.466 | Recent ATB use | 3.81 | 1.07–13.59 | 0.039* |

| Been to a high-risk region | 1.86 | 0.54–6.45 | 0.327 | Been to a high-risk region | 1.23 | 0.42–3.61 | 0.707 |

| Place of residence: Barcelona city | 1.62 | 0.52–5.04 | 0.408 | Place of residence: Barcelona city | 2.77 | 0.94–8.18 | 0.065 |

| White meat consumption | 1.07 | 0.76–1.50 | 0.717 | White meat consumption | 0.90 | 0.64–1.25 | 0.525 |

| Red meat consumption | 1.06 | 0.74–1.50 | 0.755 | Red meat consumption | 1.35 | 0.99–1.82 | 0.051 |

ESBL: extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. ATB: antibiotic. CIP-R: ciprofloxacin resistant. SXT-R: co-trimoxazole resistant.

All variables with a p value<0.05 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate models (district of residence: eixample for models 1 and 2, read meat consumption and recent ATB use in model 4). All other variables were included because there were considered clinically relevant (age, place of residence, travel history and meat consumption).

Specific risk factors for ESBL-E/K carriage were travel to a high-risk region in the past 3 years (OR 5.66; 95% CI 1.07–29.9) and living in Eixample district (OR 6.91; 95% CI 1.22–39.08). Risk factor for SXT-resistant E/K carriage was previous antibiotic therapy. No specific risk factors for ciprofloxacin-resistant E/K carriage were found. In our models, meat consumption (white or red) did not appear as a risk factor.

Literature systematic research and metanalysisTwenty-four articles indexed in PubMed were retrieved for further screening. Nine articles included in two meta-analyses on this topic3,4 conducted in Spain were also retrieved for screening (Fig. S2). For more information on how the studies were selected and which data were extracted, see supplementary material and Table S2. The presence of publication bias was assessed using Egger's test (Fig. S3). The 13 studies12-20 analysed in the meta-analysis covered a total of 21,760 individuals from different Spanish regions between 2001 and 2020. This gave a national pooled prevalence of community intestinal carriage of ESBL-PE of 5.8% (95% CI 4.1–7.8%) (Fig. 1). A goodness-of-fit analysis comparing the national pooled prevalence derived from the meta-analysis with the ESBL carriage rate reported in the present study (10.4%) showed a statistically significant difference (p=0.027).

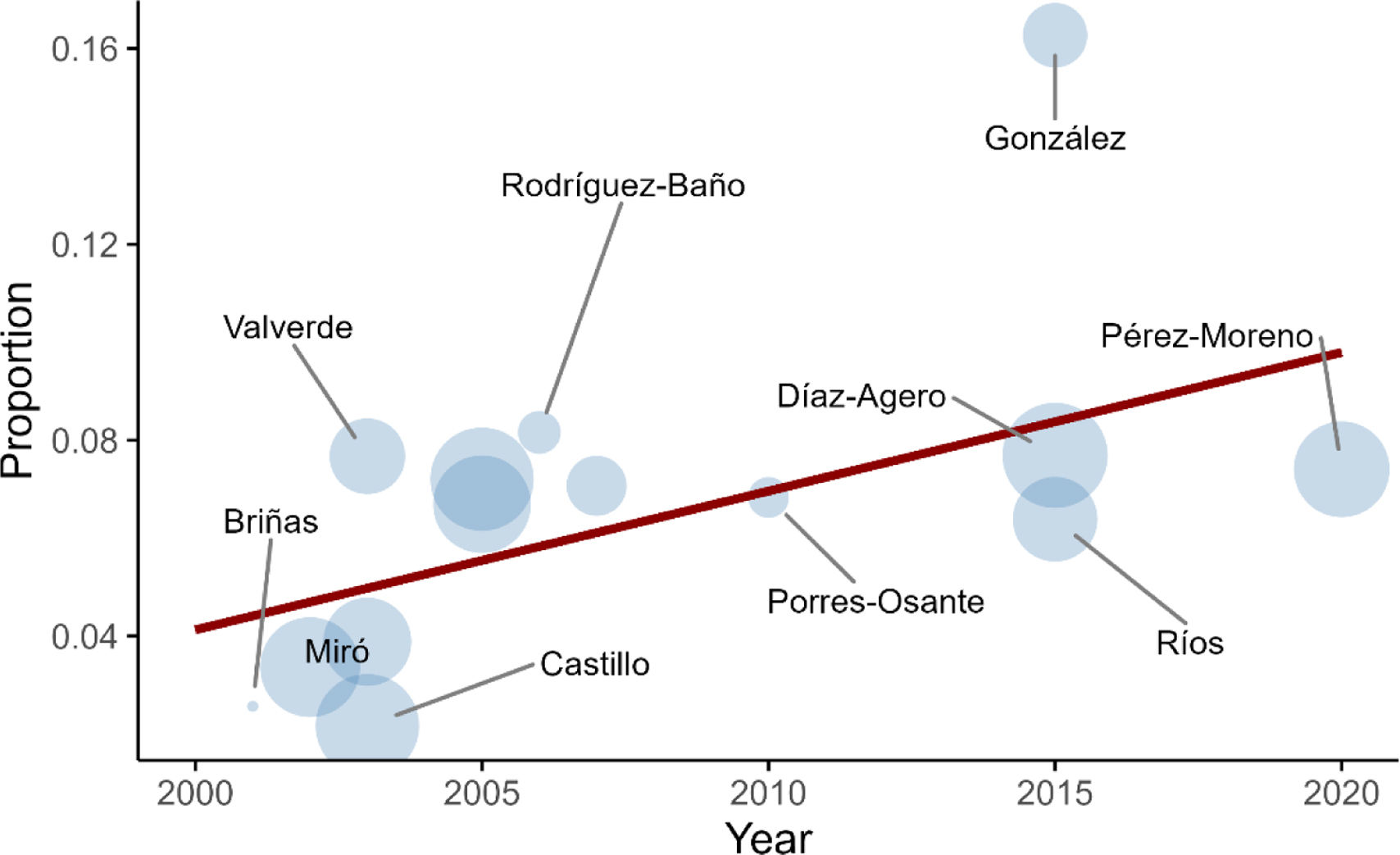

Results from linear meta-regression analysis, which included the present study, showed that year of study was positively associated with prevalence (β=0.0057; p-value=0.031). Results are shown in Fig. 2.

DiscussionOur study shows that the prevalence of faecal colonisation by multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales (23.7%) and ESBL-PE (10.4%) among healthy individuals in Spain is not negligible. The prevalence of ESBL-PE confirms and exceeds the results of previous studies performed in our country, showing an overall pooled prevalence of 5.8% and a steady increase per year. The reported ESBL-PE prevalence among participants included in our study did not differ from the estimated one by 2020 via linear meta-regression analysis of the time trend of ESBL-PE carriage in Spain. These results strengthen confidence in the methods used and reduce the risk of selection or information bias.

ESBL-PE prevalence being positively correlated with year of study, coincides with the existing evidence informed by other meta-analyses of an annual steady increase in the overall global pooled carriage rate. The worst projections estimate an ESBLE-PE prevalence of 43% globally by 2030 (with an annual increase of 1.5%).1 There is limited data from other European countries for comparison. In the Netherlands, a study including 4177 participants from the general population reported an ESBL-PE carriage rate of 5.0% (95% CI: 3.4–6.6%),21 less than half the prevalence observed in our study.

Given the poorer prognosis of patients with ESBL-PE infection,5 these increasing rates, together with the high co-resistance detected in ESBL-PE, offer a future scenario in which, if no action is taken, carbapenems may frequently have to be used as empirical treatment of systemic or organ-affecting bacterial infections due to Enterobacterales, and not only for patients with recognised risk factors for multi-drug resistant Enterobacterales carriage.22 According to the projection made in this study, this assumption could be a reality in Spain in 2050, when ESBL-PE carriage rates in the community will have reached 20%. This threshold has been used by guidelines to advise against empirical treatment with fluoroquinolones in pyelonephritis,23 since resistance prevalences as high as 50% have been reported in community-onset healthcare-associated urinary tract infections in this country.24

With regard to the molecular characterisation of beta-lactamase genes, our results coincide with those reported in other studies conducted in Spain, in which CTX-M type enzymes predominate in healthy individuals, with the blaCTX-M-15 variant being the most prevalent.25 As for sequence types, the most frequently detected E coli isolates (ST131 and ST69) in our study have also been described as prominent infection isolates globally.26 In addition, three K. pneumoniae isolates belonged to the same sequence type, suggesting some direct relation among carriers which could not be further confirmed.

Consistent with previous reports,4 previous antibiotic consumption and travel to regions with high ESBL-PE prevalence were found to be associated with carriage of antimicrobial resistant bacteria. These results could be related to selective pressure on antibiotics prescribed in the community, and increased faecal-oral, human-to-human transmission associated with poor hygiene in regions where ESBL-PE prevalence is high (such as Vietnam, Laos or China).1 Spanish guidelines for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections suggest that recent travel to a region of high ESBL-PE prevalence should be considered when deciding whether ESBL coverage with carbapenems is needed.22 However, this risk factor has not yet been included in any of the predictive scores currently used in clinical practice for infection due to ESBL-PE at the time of hospital admission.

Living in the city centre of Barcelona (specifically, the Eixample district, which is densely populated) was also found to be a risk factor associated with carriage of antibiotic resistant bacteria and, specifically ESBL-producing Enterobacterales. This result fits the theory that more crowded areas may facilitate human-to-human transmission.27

Although the use of antibiotics in veterinary practices raised concerns that animal-derived food products represent an important route of acquisition, meat consumption (white or red) did not appear to be a risk factor in our study. Overall, these results could support faecal-oral human-to-human transmission as the main route of ESBL-PE acquisition in the community, as Mughini-Gras L et al. recently demonstrated.10 In their study, 60% of community-acquired ESBL E. coli was attributable to human-to-human transmission, whereas food accounted for about 20%. The same conclusion was reached by a recent study from the UK,28 which found few resistance genes common to both livestock and humans. Food has also been posited as the most important non-human source for the acquisition of ESBL-PE.10 Direct exposure to products colonised by ESBL-PE could be one explanation. Another suggested mechanism is the ingestion of antibiotic residues that promote the emergence and selection of resistance genes in the human microbiome.29 Significant amounts of these antibiotic residues have been found, mainly in animal source foods.30

In terms of limitations, the study population is not representative of healthy young adults living in Barcelona, as only university students were included, and consequently subjects from less favourable socioeconomic backgrounds were less likely to be selected. However, unlike other well-known bacteria, such as Helicobacter pylori, ESBL-PE carriage has not been linked to lower socioeconomic groups.21 For this reason, we consider it unlikely that the real prevalence among healthy young adults was underestimated. The risk of measuring hospital-acquired bacterial carriage was reduced by including only medical students in years 1 and 2 (without contact with medical care facilities). Moreover, the prevalence seen within young adults may be similar in other age groups as ESBL carriage status has not been associated with this variable. Exposure assessment is not likely to be greatly affected by recall bias, as the subjects answered the questionnaire without knowing their colonisation status, and there is no reason to think that participants carrying resistant bacteria would report differently from non-carriers. Even so, real differences between groups could have been overlooked due to low statistical power.

Our results, together with the existing evidence, may support the development of updated predictive scores for ESBL-PE infection at hospital admission, which should include recent travel to a region of high ESBL-PE prevalence, and living in crowed city districts as additional criteria for suspected ESBL-PE infections.

Further investigations with larger sample sizes should address the role of dietary intake as a possible acquisition pathway in more detail, focusing on non-animal food products such as vegetables and fruit, which could represent an important reservoir for resistant bacteria. Measuring the levels of antibiotics present in food products, as well as in biological samples from subjects, may help determine whether long-term low dose antibiotic exposure contributes to this increasing prevalence of resistance prevalence.

Finally, given the increasing rates of antimicrobial resistant and ESBL-PE carriage among healthy individuals in Spain, general measures like community surveillance plans and antimicrobial stewardship programmes should be implemented in an effort to slow the progression and reduce the potential deleterious effects of this concerning issue.

None.