After hospitalization for COVID-19, patients may present impairment in functionality and require physical therapy after hospital discharge for functional recovery.

ObjectiveTo understand the association between Covid-19 functional impacts and physical therapy indication and access 30 days and 1 year after hospital discharge of severely and critically ill patients.

MethodsCross-sectional study with two assessments: 30 days and one year after hospital discharge, in individuals ≥ 18 years of age, admitted to a referral hospital in São Paulo between June 2020 and July 2021. A convenience sample of 345 patients was used. The Poisson test was used to estimate the prevalence ratio for the association between Covid-19 functional impacts and physical therapy indication and access, with ≤ 0.05 considered significant.

ResultsOf the 185 patients included, 67 % (n: 104) were indicated for physical therapy and the majority (53 %; n:79) could not access it 30 days after hospital discharge. Post-Covid-19 functional limitations were associated with physical therapy indication (PR: 1.69; 95 %CI 1.1–2.5) and impairment in basic activities of daily living (BADLs) with access 30 days (PR: 1.81; 95 %CI 1.2 -2.6) and 1 year after discharge (PR: 1.70; 95 %CI 1.2–2.3). Physical therapy indication was significant, with a 4.07 and 2.06 likelihood of access 30 days and 1 year after discharge.

ConclusionDespite the lack of functional criteria at discharge, patients with poor functional performance perceived the need for physical therapy indication and referral. Indication was essential for access to physiotherapy within the healthcare network.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) isaninfectiousdisease caused by the SARS-CoV-2virus,1whichwasfirst identified inChinainDecember 20192InBrazil, thefirstcasewasconfirmedinFebruary 2020, with >37 million cases andalmost 705,000 deaths recorded by early November 20233Its presentation canbesymptomaticorasymptomatic2 This multi-organdisorderaffectstherespiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, neurological, andmusculoskeletal systems4

About15 and 5 % ofinfectedpeopledevelopthesevere and critical forms ofthedisease, respectively, with complications including respiratoryfailure, acuterespiratorydistresssyndrome (ARDS), sepsis, septicshock, thromboembolism, and multipleorganfailure2,5,6Severeandcritical patients requirehospitalizationandmay experience complications linked tolengthofstay, bed rest, and useof sedatives, among others, leadingtofunctional impairment. This conditionisknownaspost-intensivecaresyndrome (PICS) andcanpersistupto 5 years after hospital discharge2,7,8

Thesepost-hospitalization complications canaffectbodily functions and structures, limiting performance in basic (BADLs) andinstrumental activities ofdailyliving (IADL), the former relatedtopersonalcareandmobility and the latter totheabilitytointeractwiththeenvironment9

As a result, thePanAmericanHealthOrganization highlights theneedtocreateandadaptpublicorprivatereferral services to rehabilitate individuals after Covid-19, promoting thecontinuityofcareandrehabilitationafterdischarge10However, forthisto occur, physiotherapy must be indicatedand patients must have accesstotheservice, that is, "theabilitytoreachandreceiveappropriatehealth services in situations whereaneedforcareis perceived"11

Despitethe obvious needforphysicaltherapyafterhospitaldischargedueto Covid-19 and PICS sequelae,12,13thefunctionalcriteriafor referral atdischargeare unclear, falling to healthcare professionals to recommend physicaltherapy. Thus, understandingfunctional impacts andcriteriaforreferralafterhospitaldischargeisessential to ensure efficient and timely accesstohealthandrehabilitation services forthecontinuityofcomprehensivehealthcare.

Thus, the present study aimed tounderstandthe association between Covid-19 functionalimpacts and physical therapy indicationandaccess 30 days and one year after hospital discharge ofseverely andcritically ill patients.

MethodsStudy designThis cross-sectional times series study involved two assessments, conducted 30 days and one yearafterhospitaldischarge.

SettingIndividuals ≥ 18 years ofageofboth sexes, diagnosed with COVID-19 and admitted toa referral hospitalforsevere cases inSão Paulo state, Brazil, betweenJune 2020 andJuly 2021 were included. Thestudywas approved bytheEthicsCommitteeofthe Clinics Hospital of the University of Sao Paulo’s School of Medicine - HC-FMUSP (CAEE: 34,115,720.5.0000.0068), andall participants signed an InformedConsentForm (ICF).

ParticipantsInclusioncriteriawere hemodynamically stable individuals with preserved or corrected visualandauditoryacuity, capable of understanding simple commands. Excluded were patients unavailableonthescheduled assessment days, those withcognitiveimpairments that prevented them from understanding the instruments applied, and unstable clinical parameters on assessment days, as well as duplicate medical records, andmissingessentialdata.

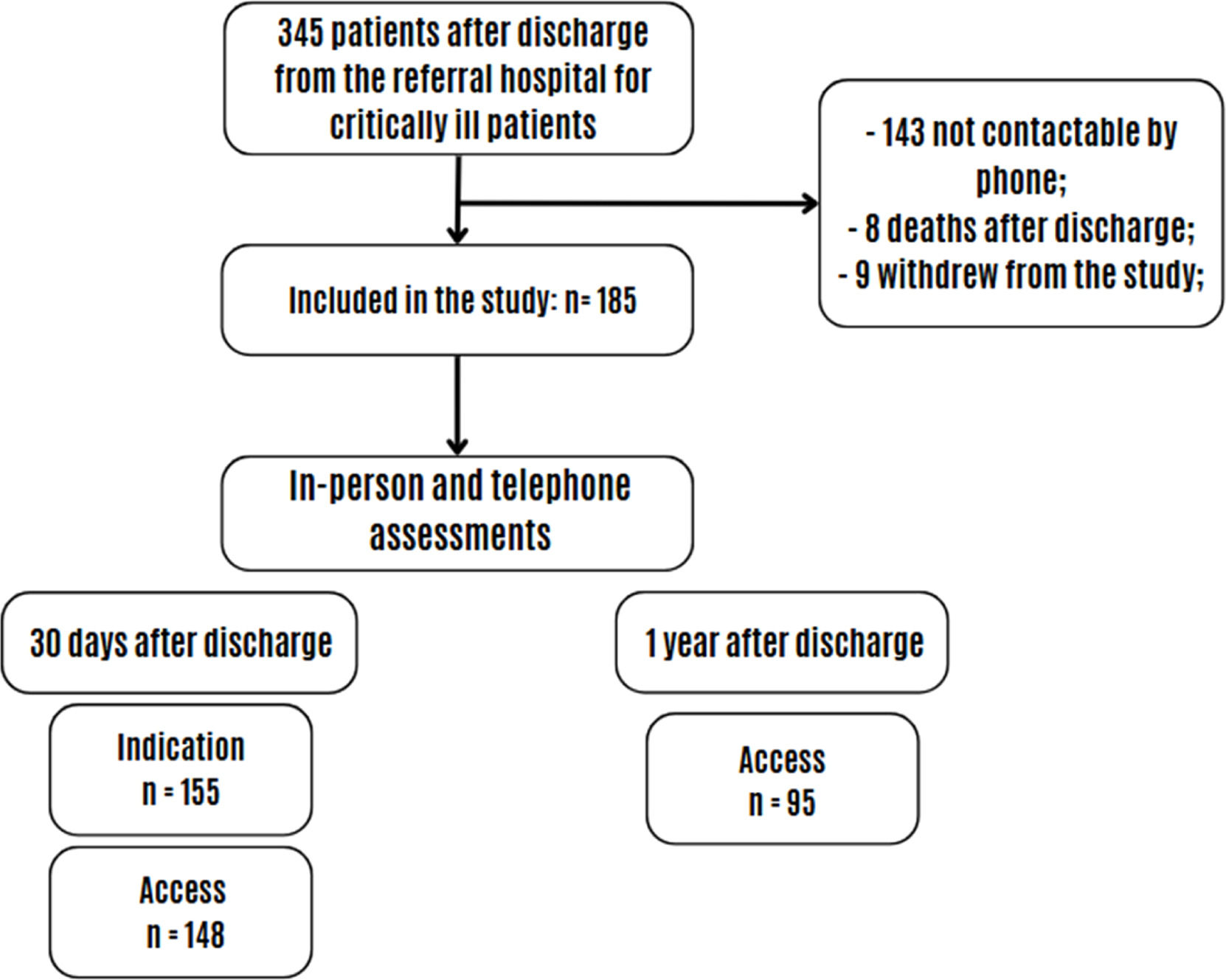

Study sizeSince the study was conducted during the criticalperiodofthe Covid-19 pandemic, when healthcare services were overwhelmed, aconveniencesampleof 345 patients wasused. Patients were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in the study, with assessments conducted by phone and in person 30 days and 1 year after discharge. Atotalof 185 peopleagreedto take part inthe study. Statistical powerforphysicaltherapy indication was 98.43 %, 10.80 % for accesstophysicaltherapy 30 days after discharge, and 97.65 % after one year, considering a 95 % confidenceinterval.

VariablesThe dependent variables were i. physical therapy indication, ii. access to physical therapy 30 days after discharge, and iii. access to physical therapy one year after discharge. Physical therapy was considered indicated when participants reported that it had been recommended or that they needed to undergo physical therapy. Access to physical therapy was considered positive when they cited the location where they were receiving physiotherapy, both 30 days and 1 year after hospital discharge.

The independent variables were age, sex, race, marital status, schooling level, income, length of hospital stay, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, and the reason for physical therapy indication. Functional impacts were measured using different instruments, based on changes in the following variables: post-Covid-19 functional impacts, using the Post-Covid-19 Functional Status (PCFS) scale14; IADLs, via the Lawton scale15; BADLs, according to the Katz scale16 and Barthel Index17; frailty, with the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)18; sarcopenia, by Sarcopenia Risk Screening (SARC-F)19; cognition, using the 10-Point Cognitive Screener (10-CS)20; perceived fear of falling, by the Falls Efficacy Scale – International (FES-I)21; muscle fatigue, in accordance with the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)22 scale; mobility, via Life Space Assessment (LSA)23; balance, by the BESTest Brief24; functional capacity, with the Sit-to-Stand Test (5 times)25; handgrip strength, using handheld dynamometry26; respiratory function, via spirometry27; and functional mobility, by the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test with a G-walk sensor28

Data were collected and stored using Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap) software.

Statistical methodsData normality was tested in Stata 14 and considered non-parametric. Descriptive measures of central tendency and dispersion, as well as percentages, were used. The prevalence ratio was measured via Poisson distribution, considering the association between Covid-19 functional impacts (post-Covid-19 functional impact, instrumental activities of daily living, basic activities of daily living, frailty, sarcopenia, cognition, perception of fear of falling, muscle fatigue, mobility, balance,functional capacity, handgrip strength, respiratory function, functional mobility) and i. physical therapy indication,and ii. access 30 days and iii. one year after discharge. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

ResultsParticipantsOf the 185 Covid-19 patients included in the study, 155 participated 30 days after hospital discharge and 95 one year post-discharge, as shown in Fig. 1.

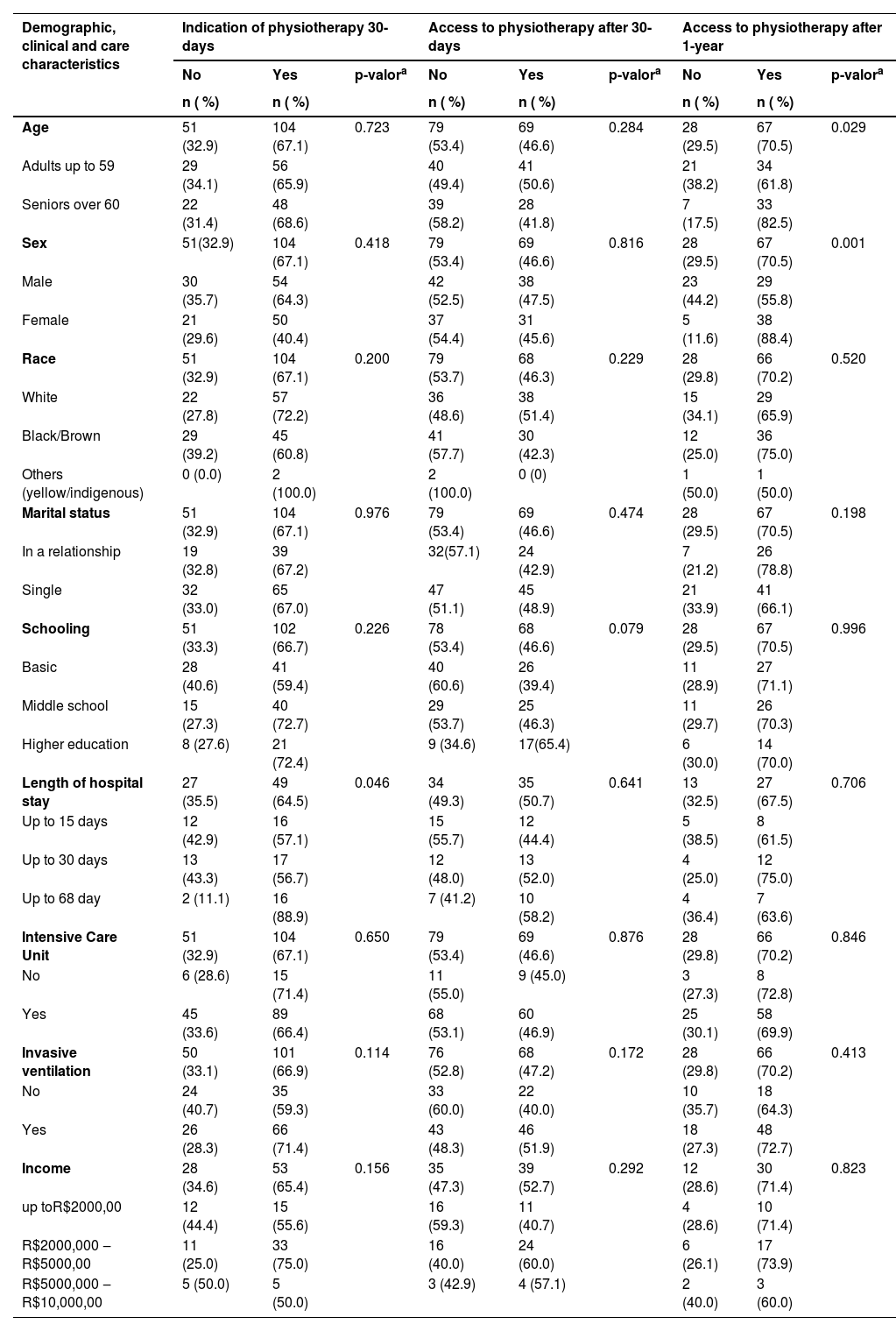

Descriptive dataTable 1 shows the demographic, clinical, and care characteristics according to physical therapy indication and access. Participants’ median age was 59 (49–67) years, 56 % (n = 103) were male, and 49.7 % (n = 90) white. The median length of hospital stay was 17.5 (10–30) days, and exhibited a significant association with physical therapy indication 30 days after discharge (p = 0.046). A significant association was also observed between age (p = 0.029) and sex (p = 0.001) and physical therapy access one year after discharge. Most patients (83.5 %) were admitted to the intensive care unit, but there was no association with physical therapy indication or access.

Demographic, clinical, and care characteristics according to physical therapy indication and access 30 days and one year post-discharge from hospitalization for Covid-19.

n, number of patients. a Poisson; R$, Brazilian currency.

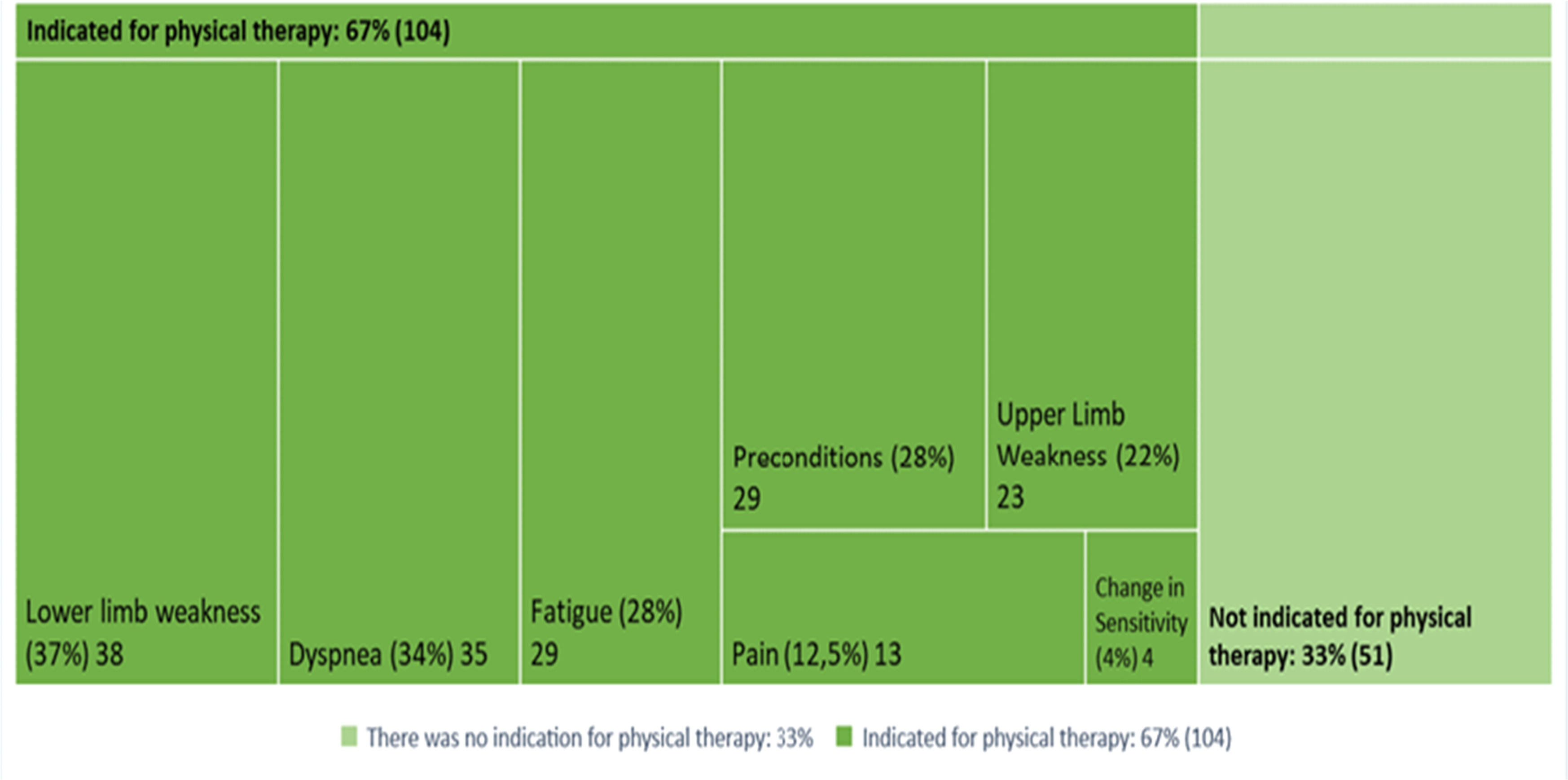

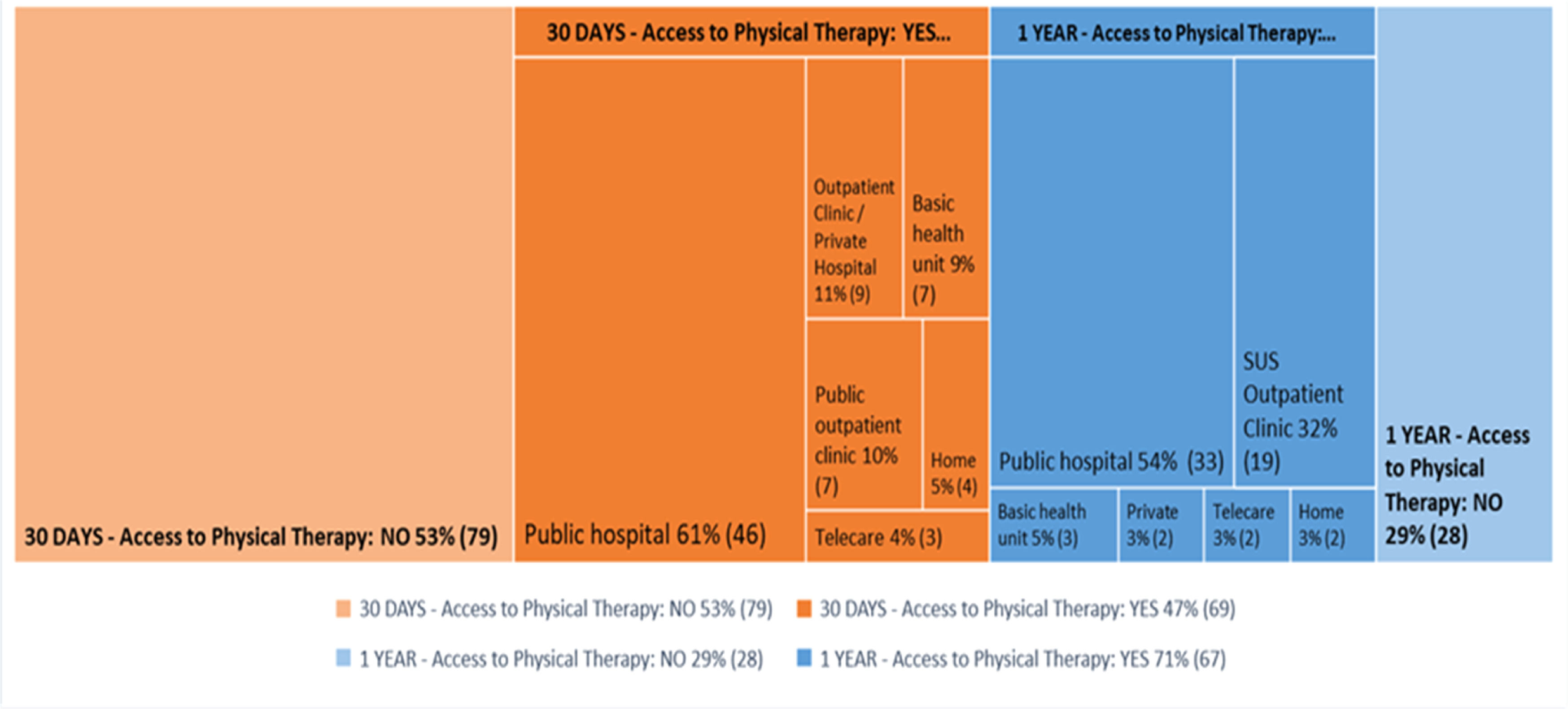

Figs. 2 and Fig. 3 show that of the 155 people who responded to the question regarding indication, 67.1 % (n = 104) were indicated for post-discharge physiotherapy. The main reasons, according to patient perception, were lower limb muscle weakness in 37 % (n = 38), dyspnea in 34 % (n = 35), fatigue in 28 % (n = 29) and pre-Covid-19 conditions in 28 % (n = 29). Of the 148 individuals who answered the question regarding access, 46.6 % (n = 69) had access to physiotherapy 30 days after discharge, with 60.5 % (n = 46) receiving it at the hospital itself. Of the 95 people that responded regarding access one year after discharge, 70.5 % (n = 67) had access to physiotherapy, 54.1 % (n = 33) of whome received it at the hospital where they were treated.

Table 2 shows the relationship between physical therapy indication and access. Almost 60 % of those indicated for physical therapy at discharge had access to it within 30 days (PR: 4.07; 95 %CI 1.9 - 8.6), and 80 % within 1 year (PR: 2.06; 95 %CI 1.2 - 3.4).

Bivariate analysis of physical therapy access 30 days and one year post-discharge after hospitalization for Covid-19, according to physiotherapy indication.

| Physical therapy access | Physical therapy indication after hospital discharge | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n ( %) | RP (CI 95 %) | p-valora | |

| Physical therapy access 30 days after discharge | 62 (59.6) | 4.07 (1.9‒8.6) | 0.000 |

| Physical therapy access 1 year after discharge | 55 (80.9) | 2.06 (1.2‒3.4) | 0.007 |

n, number of patients; PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidende interval.

There were a total of 270 results indicating some degree of functional impact, albeit with no indication for physical therapy. Some functional impacts were related to physical therapy indication 30 days after discharge, with the most significant being post-Covid-19 functional limitation (PR: 1.69; 95 %CI 1.1 - 2.5); IADL impairment (PR: 1.52; 95 %CI 1.3 - 1.7); dependence in BADLs (PR: 1.52; 95 %CI 1.1 - 1.9); significant concern about falls (PR: 1.52; 95 %CI 1.1 - 2.0); increased frailty (PR: 1.50; 95 %CI 1.0 - 2.2); greater risk of sarcopenia (PR: 1.37; 95 %CI 1.1 - 1.6); dependence when walking (PR: 1.33; 95 %CI 1.0 - 1.6) and severe fatigue (PR: 0.7; 95 %CI 0.6 - 0.9) (Table 3).

Bivariate analysis of functional impact, according to physical therapy indication and post-discharge access 30 days and one year after hospitalization for COVID-19.

PR, prevalence ratio; n, number of patients; Cl, confidence interval; BADLs, basic activies of daily living; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; LL, lower limbs; UL, upper limbs. aPoisson.

Patients’ perception regarding why they were indicated for physical therapy 30 days post-discharge were: lower limb weakness (PR: 1.71; 95 %CI 1.4 - 2.0); dyspnea (PR: 1.67; 95 %CI 1.4 - 1.9); upper limb weakness (PR:1.62; 95 %CI 1.4 - 1.8); fatigue (PR: 1.61; 95 %CI 1.3 - 1.8); preconditions for Covid-19 (PR: 1.61; 95 %CI 1.3 - 1.8) and pain (PR: 1.43; 95 %CI 1.1 - 1.7) (Table 3).

However, those who were able to access physical therapy 30 days after discharge exhibited the greatest BADL limitations (PR: 1.81; 95 %CI 1.2 −2.6) and lower-than-expected handgrip strength (PR: 1.49; 95 %CI 1.0 - 2.1). The main reason cited was pre-existing conditions prior to Covid-19 (PR: 1.72; 95 %CI 1.2 - 2.3) (Table 3).

One year after discharge, the greatest access to physical therapy was observed in patients with moderate (PR: 1.63; 95 %CI 1.2–2.2), and high (PR: 1.65; 95 %CI 1.2 - 2.2) BADL limitations (PR: 1.70; 95 %CI 1.2–2.3), as well as concern about falls and dependence when walking (PR: 1.56; 95 %CI 1.1 - 2.1) (Table 3).

DiscussionBased on the results obtained, 67 % of severely and critically ill patients who required hospitalization due to Covid-19 were indicated for physical therapy after discharge. However, the majority (53 %) were unable to access it within 30 days of discharge, taking up to one year to receive this care. Some patients exhibited functional impairment but were not recommended for post-discharge physical therapy. Receiving a physical therapy indication was significant, with a 4.07 and 2.06 likelihood of timely access to the service 30 days and one year after discharge, respectively. Timely and comprehensive continuity of care requires that patients receive a counter-referral to primary health care at discharge to ensure better coordination by health and physiotherapy services and provide more efficient treatment and use of resources29,30

The literature demonstrates the need for post-discharge rehabilitation due to functional sequelae resulting from the disease and hospitalization. However, there is no clear pathway for accessing health services7,31–33 Almeida et al. (2023)34 described patients' perception of a so-called "care gap" between hospitals and follow-up services, highlighting the fragility of the rehabilitation indication and post-discharge access process.

Problems caused by the Covid-19 pandemic include difficulty receiving a physical therapy indication and accessing the service after discharge. Although the literature suggests different scales for assessing respiratory dysfunction, muscle strength, balance, mobility, dyspnea, and fatigue at hospital discharge and recommendations for rehabilitation[35–38] due to sequelae from hospitalization for Covid-19, it falls to healthcare professionals to indicate physiotherapy and provide recomendations on how and where to access treatment.

Our study shows that both functional impacts and signs and symptoms resulting from Covid-19 were clear reasons for recommending post-discharge physical therapy, with PR ranging from 0.07 to 1.71. However, there were few criteria with regard to accessing physical therapy.

Covid-19 infection, hospitalization, and ICU admission can lead to functional loss, disability, and ADL limitations,2,7,8 which is corroborated by our findings.

Of the functional impacts, BADL impairment was related to physical therapy indication and access 30 days and one year after discharge. To date, there is no established threshold for ADL limitations to recommend physical therapy. However, physiotherapy is known to promote functional independence. Research with this population has identified ADL limitations that can persist up to 6 months after discharge for hospitalization due to Covid-1939 These limitations demonstrate the need for post-discharge rehabilitation since they affect the quality of life of individuals40 Otoala et al. (2023)41 observed favorable functional evolution at the 6-month follow-up. However, 22 % of patients exhibited some degree of persistent frailty six months after discharge.

Post-Covid-19 functional limitation was related to physical therapy indication, with 87 % of patients displaying functional impairment after hospitalization for Covid-19. This corroborates literature findings, whereby most hospitalized patients have some degree of functional limitation according to the PCFS scale42 This scale evaluates the extent to which post-Covid-19 functional status is altered by disease sequelae and length of hospital stay, affecting quality of life and independence.

Fatigue was also a criterion for indicating physical therapy, with 76 % of patients exhibiting severe fatigue after discharge. Our findings are similar to those of Otoala et al. (2023), who reported fatigue in 69 % of participants 3 months after discharge41 Fatigue impacts ADLs, social activities, and mood.

Handgrip strength is an indicator of global strength and, in the present study, was a criterion for physical therapy access 30 days post-discharge, with decreased handgrip strength in 27 % of patients. This result is similar to that of Qorolli et al. (2023), who reported lower handgrip strength in 33 % of the study sample43

The most frequent reason for indicating continued physical therapy was lower limb weakness (36.5 %), followed by dyspnea, fatigue, pre-Covid-19 conditions, and pain, possibly due to functional limitations resulting from these symptoms. The majority (67 %) of participants in our study received some form of physiotherapy recommendation, but this was based on the subjective assessment of individual professionals and physical therapy indication was not proportional to access. Araya-Quintanilla et al. (2023) conducted a literature review on rehabilitation recommendations and effects and the main post-Covid-19 symptoms, with a greater likelihood of these persisting after hospitalization, but without referencing criteria for indicating continued physical therapy. They also highlighted the positive effects of rehabilitation programs with a multidisciplinary team, including physiotherapy, on recovering functional capacity and quality of life44

As such, it is important to consider functional assessment combined with signs and symptoms as a parameter or criterion for physical therapy indication, in addition to the hospital discharge report and clinical evaluation, in order to ensure timely and effective recommendations and access to care. This will also enable better coordination in healthcare networks for physical therapy care continuity.

It is important to note that, in addition to the configuration and structure of the health system to address care needs, the pandemic also contributed to access difficulties. Hospital and specialist care were considered priorities for regular follow-up of Covid-19 health problems45,46

In the present study, of the 47 % of the patients who had access to physical therapy in the first 30 days after discharge, the service was largely provided at the public hospital where they were hospitalized in the city of São Paulo (61 %), followed by outpatient clinics/private hospitals (11 %), basic health units (9 %) and public outpatient clinics (9 %). After one year, 71 % of patients had access to physical therapy, 54 % of whom received it at the public hospital in São Paulo where the research was conducted, 32 % at SUS outpatient clinics and 5 % at Basic Health Units.

These findings are similar to those of Almeida et al. (2023), who reported that the vast majority of respondents were contacted by the hospital where they had been hospitalized for continued rehabilitation, followed by an active search for patients themselves, also highlighting access difficulties due to ack of knowledge about the care network on the part of professionals, and problems in post-discharge counter-referral flow. This resulted in patients abandoning treatment between hospital discharge and the beginning of rehabilitation, representing a rupture in care trajectories34

In this respect, we highlight the need to establish more specific functional criteria, signs, and symptoms for physical therapy indication at discharge as part of the dehospitalization process and to reduce the post-discharge "care vacuum" of critically ill patients. This strategy is important beyond Covid-19, since the care vacuum and challenges inherent to rehabilitation in primary and specialist services prompt users to seek private care. This compromises household income, exacerbates fragmentation and increases the direct search for focal specialists, weakening guaranteed access to physiotherapy. To avoidthis scernario, physiotherapy should be provided via primary health services to ensure comprehensive and coordinated care supported by specialized public service and rehabilitation networks, in line with the principles of humanized care34

Finally, it is important to underscore the scarcity of research regarding continuity of care with post-discharge physical therapy indication and access following hospitalization for Covid-19. Thus, our study contributes to bridging this gap by assessing the associations between Covid-19 functional impacts and physical therapy indication and access after discharge in severely and critically ill patients hospitalized for Covid-19.

Strengths and limitationsThe sample consisted of patients with Covid-19 admitted to a referral hospital for critically ill patients in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. No other study has analyzed Covid-19 functional impacts and continuity of physical therapy care post-discharge in critically ill patients.

The results obtained should be interpreted considering the following limitations: the study population was extracted from a convenience sample of critically ill patients during the pandemic and as such, the results are not generalizable to mild or moderate cases of Covid-19. Given the type of sample used, selected during the critical stage of the Covid-19 pandemic, some areas of the analysis may have been subject to selection bias, such as collider bias and missing data. Symptom severity, time until physiotherapy access and possible factors related to lack of access could not be assessed.

ConclusionPhysical therapy was indicated for most of the severely and critically ill patients studied, but without timely access after hospital discharge. Despite the lack of functional criteria at discharge, patients with poor functional performance perceived the need for physical therapy indication and referral. However, an indication for continued physical therapy after discharge was essential for timely access to these services within the healthcare network. In light of the above, in addition to the use of functional criteria, it is recommended that physical therapy indications and counter-referrals be included in the hospital discharge report.

FundingThe study was supported by grants 402,698/2020–0 and 312,279/2018–3 from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and 19,618–8/2018 from the Sao Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP)."

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.