Most studies about personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying have been carried out in Western countries without analysing if adolescents are involved only in personal bullying, ethnic-cultural bullying, or both. This study is based in Peruvian Amazonia, a multi-cultural context where not much research has been done, with the aim to understand the overlap of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying as well as their predictors. The sample is made up of 607 students (48.3 girls and 51.7% boys) between the ages of 12 and 19 (Mage=14.5, SD=1.69) from a region in Peruvian Amazonia which completed a self-report questionnaire. Ethnic-cultural bullying and personal bullying are prevalent and overlapped phenomena, being the ethnic-cultural group of the Native Americans the most implicated in victimization and/or aggression. Regarding the overlapping roles resulting from personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying (mixed roles), personal victimization is predicted by low assertiveness, and it is related to older age. The mixed role of personal and ethnic-cultural victim is related to a high affective empathy, an indigenous ethnic-cultural group and low conflict resolution skills. The role of personal bully-victim and ethnic-cultural victim is related to being older. Personal and ethnic-cultural bully-victims are older males with lower self-esteem and assertiveness. The results are discussed in relation to education programs about prevention and mitigation of bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying.

La mayoría de los estudios sobre el bullying personal y el bullying étnico-cultural se han realizado en países occidentales y sin analizar si los adolescentes se implican en el bullying personal solo, en el bullying étnico-cultural o en ambos fenómenos a la vez. La presente investigación se realiza en la Amazonía Peruana, un contexto pluricultural poco estudiado, para comprender el solapamiento en la implicación en el bullying personal y étnico-cultural, junto con sus predictores. Han participado 607 escolares (48.3% chicas y 51.7% chicos) de entre 12 y 19 años (M=14.5 años, DT=1.69) quienes han cumplimentado un cuestionario auto-informe. El bullying étnico-cultural y el bullying personal son fenómenos prevalentes y solapados, siendo el grupo étnico-cultural de los indígenas el más implicado en victimización y/o agresión. En los roles solapados resultantes de bullying personal y bullying étnico-cultural (roles mixtos), el rol de víctima de bullying personal se predice por las menores puntuaciones en asertividad y se relaciona con la mayor edad. El rol mixto de víctima personal y étnico-cultural se relaciona con ser indígena y se predice por las mayores puntuaciones en empatía afectiva y menores en resolución de conflictos. El rol de agresor-victimizado personal y víctima étnica se relaciona con la mayor edad. Los agresores-victimizados personales y étnico-culturales son chicos, de mayor edad, con bajas puntuaciones en autoestima, asertividad y resolución de conflictos. Los resultados se discuten en relación con los programas educativos para la prevención y paliación del bullying y del bullying étnico-cultural.

Bullying, in its various forms, has been studied for over four decades. However, most of these studies have been conducted in highly developed countries. Until 2015, less than 25% of the articles related to bullying originated from outside Europe and the United States (Zych et al., 2015a), thus forming a research gap about bullying in many parts of the world. In Latin America, where research into bullying is still relatively uncommon, there have only been studies in the last 15 years (Herrera-López et al., 2018). Meanwhile, worldwide, the vast majority of studies of ethnic-cultural bullying have been conducted in large populations which were highly homogeneous as regards ethnic-cultural diversity, and no results based on diversity have been recorded (Xu et al., 2020), with the majority of interventions focusing on stigma which are prevalent in European and North American countries but almost non-existent in Latin America (Earnshaw et al., 2018). Additionally, many studies into personal bullying have not looked in any depth into the simultaneous relationship with other types of bullying, such as ethnic-cultural bullying (Baysu et al., 2016; Monks et al., 2008). Indeed, there could be an overlap between different roles of personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying, which could give rise to different combinations of mixed roles.

Taking into account the limitations of previous studies, the present study focuses on personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying in Latin America, where the number of projects is still low, despite ethnic-cultural differences being the second commonest cause of bullying worldwide and represent between 7% and 11% of cases in Latin America (UNESCO, 2018). The objective of the study was to discover the prevalence of ethnic-cultural bullying according to the different ethnic-cultural groups, the overlap between personal and ethnic-cultural bullying, and its predictors in adolescents from the Peruvian Amazon.

Personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullyingBullying is an intentional aggressive behavior which is repeated over time and occurs in an imbalance of power between aggressors and victims, by which the aggressor or aggressors subdue their victims (Olweus, 1996). Although studies on bullying have proliferated in recent decades, there have been few studies to date on ethnic-cultural bullying. The corpus of knowledge on this phenomenon, also referred to as traditional or personal bullying, has therefore been formed by studies focusing on bullying which do not take into account the motivation of the aggressor (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Alcívar et al., 2019; Baysu et al., 2016; Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al., 2019; Monks et al., 2008; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2015, 2014).

However, over the past two decades, there has been an increase in studies on different types of bullying based on the social stigmas related to ethnic-cultural interpersonal differences, sexual orientation, gender, special educational needs and disability (Earnshaw et al., 2018; Russell et al., 2012). These phenomena of bullying are based on manifest or subtle social prejudices which, in turn, are founded on social dominance, whereby a scheme of social asymmetry is projected, in which the person with one or more diverse traits is preconceived as subordinate or inferior to other people showing traits which can be attributed to the prevailing desirable stereotype, as dictated by the social context (Żemojtel-Piotrowska et al., 2020).

Ethnic-cultural bullying among schoolchildren can be defined as a phenomenon of interpersonal violence in which the victims are attacked with the unfair excuse of their ethnic-cultural differences, such as being from another country, or having another culture of origin, another religion, another language, or a different skin color (Rodríguez-Hidalgo & Ortega-Ruiz, 2017). The roles of victim, aggressor, bully-victim and not-involved have been reported both in personal bullying (Salmivalli et al., 1996) and in ethnic-cultural bullying (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al., 2019).

Personal bullying is a serious problem existing in schools in different countries and regions (Zych et al., 2015b). International data from 144 countries reveal that a third of students have suffered bullying in the last month (UNESCO, 2018). In Latin America, studies show a greater involvement than in Europe (UNICEF, 2014), with an estimated level of victimization between 4.6% and 50% and of aggression between 4% and 34.2% (Garaigordobil et al., 2018).

In Peru, personal bullying is an extremely worrying phenomenon. From 2013 to 2018, 26,285 cases of bullying were reported, and the figure continues to rise (Rivera et al., 2018). A recent study in the Andean region estimates victimization at 37.3%, being more frequent among males than females (Amemiya et al., 2022), a difference which may be a result of the sexist culture prevalent in Peru and Latin America (Meza, 2016). Another study gives the prevalence of bullying in Peru as 60.3%, of which 25.6% are victims, 17.6% aggressor-victims and 16% aggressors (Zeladita-Huaman et al., 2022). Similar percentages have been found in studies carried out in the Peruvian Amazon, where an involvement of 60% has been found, with 24.2% victims, 4.5% aggressors and 28.7% bully-victims (Martínez et al., 2020). These studies show a higher percentage of involvement than those found in one meta-analysis focusing on all Latin American countries (Herrera-López et al., 2018).

Ethnic-cultural bullying among schoolchildren is also a global problem. In the United States, one in four reports of bullying is attributed to ethnic-cultural causes (US Department of Education, 2018) and it has become the main cause of bullying in California (Gill & Govier, 2023). One North American longitudinal study, focusing on ethnic-cultural victimization towards indigenous people, revealed that 38.6% of its members were involved: 16.7% as victims, 15.1% as aggressors and 6.8% as bully-victims (Melander et al., 2013). In Spain, statistics show that 12.9% of all students have been ethnic-cultural victims, 3.8% ethnic-cultural aggressors and 7.7% ethnic-cultural bully-victims (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al., 2019). Although there are some pioneering works on the subject, there has, however, been little research into ethnic-cultural bullying worldwide (Xu et al., 2020), and even less in the extensive South American region, where there have been practically no interventions at all (Earnshaw et al., 2018).

Personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying share many of the same characteristics. However, very few studies have focused on the overlap between these two phenomena. Among those published to date, some illustrate the relationship between being a victim of personal bullying and being a victim of ethnic-cultural bullying (Cardoso et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2015, 2014), as well as the distinction between being a victim for discriminatory reasons of aggressors from an ethnic-cultural group different from their own and being a victim in their own ethnic-cultural group (Benner & Wang, 2017). Along the same lines, a study carried out by Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al. (2019), highlighted the overlap between personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying in a sample of 27,379 participants in Spain. Here, it was found that of the bully-victims in personal bullying, 85% have also been ethnic-cultural bully-victims and 20.7% ethnic-cultural victims. As regards the victims of personal bullying, 73% have also been ethnic-cultural victims and 7.9% ethnic-cultural bully-victims. It has also been noted that 59.4% of personal bullying aggressors have been ethnic-cultural aggressors.

It has also been observed, in samples of adolescents from Canada, the Netherlands and Spain, that some students who recognize themselves as ethnic-cultural victims do not recognize themselves as victims of personal bullying (McKenney et al., 2006; Monks et al., 2008; Verkuyten & Thijs, 2006). This fact, supported by other observations, for instance that being a victim of ethnic-cultural bullying is considered more harmful than being a victim of personal bullying (Felix et al., 2009; Garnett et al., 2014; Russell et al., 2012), some researchers have suggested that, for many adolescents, there is a major difference between being the object of discriminatory violence produced by personal motivation and that caused by ethnic-cultural motivation (Monks et al., 2008; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2015, 2014). All this is backed up by the growing number of studies conducted in societies with highly-developed economies and advanced educational systems. However, it is not known if the same holds for developing societies and with less well-resourced educational systems.

Here, the existing scientific studies do not follow a consistent line as regards whether belonging to an ethnic-cultural minority in adolescents constitutes a greater risk of being involved in personal bullying. The results of some studies certainly suggest that being a member of an ethnic-cultural minority group entails a greater risk of involvement in bullying (Llorent et al., 2016; Maynard et al., 2016; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2020) either as aggressor (Tippett et al., 2013; Tolsma et al., 2013), victim (Kisfalusi et al., 2020; Llorent et al., 2016) or bully-victims (Goldweber et al., 2013; Llorent et al., 2021). Indeed, one meta-analysis covering 53 European and North American articles found that Afro-descendants and indigenous people have reported more situations of personal bullying than whites and that there is a distinct lack of studies which compare whites and mixed races in this respect (Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, 2018). However, another meta-analysis analyzing 105 studies worldwide found there were no significant differences between ethno-cultural groups regarding involvement in personal bullying, and that minority ethno-cultural groups suffer more victimization in Europe than in the US, while majorities are more victimized in the US (Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, 2015). This issue therefore seems to require further study, in order to advance in the understanding of how to improve the prevention of school and youth violence in today’s increasingly ethnically and culturally diverse societies.

Most of the research into bullying has been conducted in North American and European societies, in student populations with a white ethno-cultural majority (Xu et al., 2020). However, this ethnic-cultural group is not in the majority in most societies and countries worldwide. This highlights the need to study personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying in other multicultural societies, where the white ethnic-cultural group is not a majority. Peru is a country that meets these characteristics and in which racist behaviors have been documented in aspects of daily life (Dorival-Córdova, 2018). In the Peruvian Amazon, different forms of racist discrimination exist, mainly towards different indigenous ethnic-cultural groups (Pazos, 2016), which puts many of their beliefs, languages, customs and traditions at serious risk of disappearance (Martínez-Torres et al., 2019). However, the studies carried out in Peru to date into ethnic-cultural discrimination, and especially the few carried out on bullying and ethnic-cultural diversity, are not very conclusive because they have been affected by certain limitations in sampling and procedure (Anderson, 2017).

Personal bullying, ethnic-cultural bullying, self-esteem, empathy and social skillsSelf-esteem, empathy and social skills are interpersonal aspects that play a relevant role in the prevention and alleviation of bullying (Avşar & Alkaya, 2017; Didaskalou et al., 2017; Farrington et al., 2017). Recently, studies have suggested that the predictive role of these three factors seems to carry greater weight in discriminatory bullying than in personal bullying (Espelage et al., 2017; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2021). However, few studies have looked into this aspect, or the relationship between self-esteem, empathy and social skills, and there has been very little research into the roles assumed when personal and ethnic-cultural bullying occur simultaneously.

On the other hand, there has been a great deal of research into bullying victims with low self-esteem (Álvarez et al., 2022; Martínez et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2014). One systematic review which analyses the protective factors of bullying concluded that high self-esteem is related to lower levels of victimization and aggression (Zych, Farrington et al., 2019), while another meta-analysis of 18 longitudinal studies concluded that low self-esteem predicts victimization, and vice versa (Van Geel et al., 2018).

However, very few studies have looked at the relation between ethnic-cultural bullying and self-esteem. One Spanish study showed that an ethnic-cultural minority group’s self-esteem was lower than that of the majority group, and that there was a negative relationship between personal victimization, ethnic-cultural victimization and self-esteem (Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2014). Another transnational study carried out in England and Spain concluded that ethnic-cultural victimization predicts lower self-esteem (Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2015).

As regards the relationship between empathy and personal bullying, results to date suggest that high empathy acts as a protective factor against aggression and victimization (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2006b; Zych, Farrington et al., 2019), while low empathy is a risk factor for aggression and victimization (Del Rey et al., 2015; Espelage et al., 2017; Jolliffe & Farrington, 2006a; Kokkinos & Kipritsi, 2012). One systematic review of 53 theoretical studies highlighted the relationships of the role of aggressor with low empathy; of the role of victim with high affective and low cognitive empathy; of the role of bully-victim with low empathy; and of the role of defender with high empathy (Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019). Other research has likewise found that victimization is related to high cognitive (Trach et al., 2023) and affective empathy (Fousiani et al., 2016; Martínez et al., 2020; Zych, Farrington et al., 2019). This greater level of empathy in the victims can be explained by the fact that they may be more sensitive than those not involved (Caravita et al., 2010), which makes them understand better the feelings and emotional impact felt when a victim is attacked without justification (Ortega-Ruiz, 2010). Additionally, very few studies have dealt with the relationship between empathy and ethnic-cultural bullying. However, it has been observed that low empathy is related to higher levels of ethnic-cultural aggression (Bayram et al., 2020), and that this factor plays a key role in creating prejudices towards members of other groups (Miklikowska, 2018).

Social skills, such as assertiveness, conflict resolution and communication skills, constitute behavior and cognitive routines which allow people to establish positive relationships with others (Oliva et al., 2011). A low level of social skills therefore predicts both victimization (Jenkins et al., 2017; Kochel et al., 2015) and aggression in personal bullying (Jenkins et al., 2017; Nickerson et al., 2008; Pozzoli & Gini, 2010), while good social skills provide the individual with a range of different defense strategies, and are associated with the role of defender (Elliott et al., 2019). Assertiveness, on the other hand, is related to lower levels of victimization (Avşar & Alkaya, 2017; Keliat et al., 2015) and aggression (Avşar & Alkaya, 2017; Keliat et al., 2015) in a similar way to good conflict-solving skills (Heydenberk et al., 2006). Similarly, one study focusing on the predictors of bullying in ethnic minorities found that the most important predictor was a low level of social skills (Vera et al., 2017). However, there is a considerable gap in research on the possible relationships between social skills and ethnic-cultural bullying (Garnett et al., 2014; Polanin & Vera, 2013).

Moreover, very few studies deal with the variables related to the overlap between personal and ethnic-cultural bullying. One of these, conducted in Spain and Ecuador (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Pantaleón et al., 2019), found that in both countries, ethnic-cultural victimization and aggression, personal aggression, self-contempt, and affective empathy predicted personal victimization. It also found that the levels of aggression and ethnic-cultural victimization, personal victimization, self-hatred, and being female predicted personal aggression in Spain and Ecuador.

The present studyA look at the scientific literature shows not only how personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying constitute serious problems worldwide, but also that there is a considerable research deficit in economically disadvantaged areas. However, it is precisely in these areas where such violence occurs the most (Krisch et al., 2015) and where it is most urgent to understand the phenomenon of violence, including bullying, and its associated factors (Del Rey & Ortega, 2008; Herrera-López et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Pantaleón et al., 2019). Another point revealed in the literature is that belonging to an ethnic-cultural minority can be a risk factor in personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying. However, it is not yet clear whether belonging to a minority ethno-cultural group may be a risk factor in places where the white ethno-cultural group is in the minority. Personal and ethnic-cultural bullying do seem to overlap; nevertheless, there is very little research into the involvement roles resulting from these two phenomena (mixed roles), or into the relationship between these mixed roles and self-esteem, empathy and social skills. While the relationship between these variables and personal bullying has been extensively studied, its relationship with mixed roles has not been studied in depth.

For all the above reasons, in carrying out the present study in the Peruvian Amazon were the objectives as follows: (1) to discover the percentages of involvement in the different roles of ethnic-cultural bullying and whether differences exist in involvement between ethnic-cultural groups; (2) to find out whether personal and ethno-cultural bullying overlap, and if so, to describe the resulting roles; and (3) to shed light on the predictors of the roles assumed in the overlap between personal and ethnic-cultural bullying (mixed roles). The first hypothesis, based on previous studies (Llorent et al., 2016; Maynard et al., 2016; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2020), was that we expected to find a high prevalence of ethnic-cultural bullying and differences in the levels of involvement, according to the ethnic-cultural group. The second hypothesis was that we expected to find an overlap between personal and ethnic-cultural bullying (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al., 2019). The third hypothesis was expected that low levels of self-esteem (Álvarez et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2015, 2014), empathy (Bayram et al., 2020; Espelage et al., 2017), and social skills (Jenkins et al., 2017; Kochel et al., 2015; Vera et al., 2017) predict involvement in mixed personal and ethno-cultural bullying roles.

MethodParticipantsThe study sample consisted of 607 schoolchildren from four state schools in Iquitos, in the province of Loreto (Peruvian Amazon). The participants were aged between 12 and 19 years old with a mean age of 14.5 years (SD=1.69); 48.3% were girls and 51.7% boys. The children were attending Compulsory Secondary Education in Peru (five years): 22.1% in the first year, 22.1% in the second, 17.3% in the third, 19.9% in the fourth and 18.6% in the fifth. The participants themselves stated that they belonged to different ethnic-cultural groups: 73.5% mestizo, 20.4% white, 5.9% indigenous and 0.2% others.

InstrumentsThe instrument used was a self-report made up of a battery of questionnaires, using the following sociodemographic variables: sex, age, course and ethnic-cultural group.

Personal bullying was measured with the Spanish version of the European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (EBIP-Q) (Ortega-Ruiz et al., 2016), validated in a Peruvian Amazon population by Martínez et al. (2020). The instrument consists of 14 items, seven of which refer to aggression (e.g., "I have threatened someone") and seven to victimization (e.g., "someone has threatened me"). The questionnaire is answered on a Likert-type scale from 1=no to 5=yes, more than once a week. In the present study, the questions refer to the frequency of victimization and aggression in the last two months. Adequate reliability was found in the questionnaire scores (victimization α=.79, Ω=.79 and aggression α=.78, Ω=.78); Average Variance Extracted (AVE)=.55, Composite Reliability (CR)=.93.

Ethnic-cultural victimization and ethnic-cultural aggression were measured with an adapted version of the European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire - Ethnic-Cultural Discrimination (EBIPQ-ECD) validated by Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al. (2019). The EBIPQ-ECD presents the same number of items (seven for ethnic-cultural victimization and seven for ethnic-cultural aggression) and the same response scale (Likert type) as the EBIP-Q. However, in the introductory explanation, the context was set for the participants by asking them about their experiences of discrimination using these words: "We will now ask you about any experiences of discrimination you may have had in your environment (school, friends, acquaintances) due to differences in the color of your skin, place of origin, culture or religion, in the last two months.” Thanks to this adaptation, the participants could report behaviors of aggression and ethnic-cultural victimization they have both displayed and received. The questionnaire presents a good reliability in the scores (victimization α and Ω=.84 and aggression α and Ω=.85); AVE=.43, CR=.86.

Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (1989), with a version validated in Spain in a sample of adolescents (Viejo, 2012). The instrument consists of 10 items (e.g., "I am able to do things as well as most people.") The questionnaire is answered using a Likert-type scale from 1= totally disagree to 4= totally agree, with acceptable reliability scores in the present sample (α=.67, Ω=.68); AVE=.18, CR=.69.

Empathy was measured through the Basic Empathy Scale (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2006a) in the reduced and adapted version by Oliva et al. (2011). The scale contains two dimensions: cognitive empathy, with five items (e.g., "I can often understand how others feel even before they tell me") and affective empathy, with four items (e.g., "I am easily affected by the feelings of others.") The items are answered on a Likert-type scale from 1= totally disagree to 5= totally agree. The scale scores showed good reliability in this sample (α and Ω for affective empathy=.77 and α and Ω for cognitive empathy=.84); AVE=.41, CR=.89.

Social skills were measured using the Social Skills Scale devised by Oliva et al. (2011), consisting of 12 items which group together three dimensions: communication or relational skills, with five items (e.g., "I am ashamed to speak when there are many people around,) assertiveness, with 3 items (e.g., "If I have the impression that someone is upset with me, I ask them why") and conflict resolution, with 4 items (e.g., "I usually mediate in problems between colleagues.") The response is on a Likert-type scale from 1=completely false to 7=completely true, with some items formulated negatively and others positively. The subscales present acceptable reliability scores in the present sample (α and Ω for communication skills=.78, α and Ω for assertiveness=.66, and α and Ω for conflict resolution=.69); AVE=.42, CR=.88.

ProcedureThe data was collected as part of a development cooperation project between the La Restinga Association and the University of Cordoba (Spain). The Loreto Regional Education Office were also contacted and data was collected through a collaboration agreement. Six state schools in Iquitos were contacted, of which four agree to participate. The school management approved the study, and the questionnaires were administered to one class, selected at random, in each school. The parents or legal guardians were fully informed about the objectives of the study, and all agreed to allow their children to participate. Participants were included if they were in first to fifth year of secondary school, if their parents/legal guardians allowed them to take part, and if they voluntarily agreed to do so. Students who did not have parental consent or chose not to participate when they were presented with the self-report were excluded. Before data collection, clear, precise instructions were given on how to fill in the questionnaires. The data was collected anonymously and voluntarily for approximately one hour per class in the school hall, under the constant supervision of a researcher. The participants always had the right to withdraw when they wished. No personal data that could identify the participants was collected, and the national and international legislation on ethical principles, including the Declaration of Helsinki and the personal data protection law, was followed. The study was also approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Cordoba (Spain).

Data analysisThe prevalence of the different roles of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying were analyzed, as well as their relationships with the other variables, using the SPSS statistical software, version 20 (IBM Corp., 2011). To do this, the participants were classified into different personal and ethnic-cultural bullying roles based on their responses to the items referring to victimization and aggression. Participants who answered ‘never’, ‘once’ or ‘twice’ to all the items about personal and/or ethnic-cultural aggression and victimization, were considered ‘not involved’. Participants who responded ‘once or twice a month’ or more to any item on aggression and ‘never’, ‘once’ or ‘twice’ to all items concerning personal and/or ethnic-cultural victimization were considered ‘aggressors’ (and vice versa for the victims). Finally, participants who responded ‘once or twice a month’ or more to any item on aggression and victimization were classified as ‘bully-victims’. These are the cut-off points usually used in this field (Romera et al., 2022).

Descriptive analyses were conducted to find the prevalence of involvement in personal and ethnic-cultural bullying according to ethnic-cultural group. Odds ratios were also calculated using the Campbell virtual calculator to find out if there were any differences in involvement according to ethnic-cultural group. The relationships between the predictors (self-esteem, empathy, social skills, gender and age) and the mixed roles were analyzed using a multinomial logistic regression analysis and a correlation analysis.

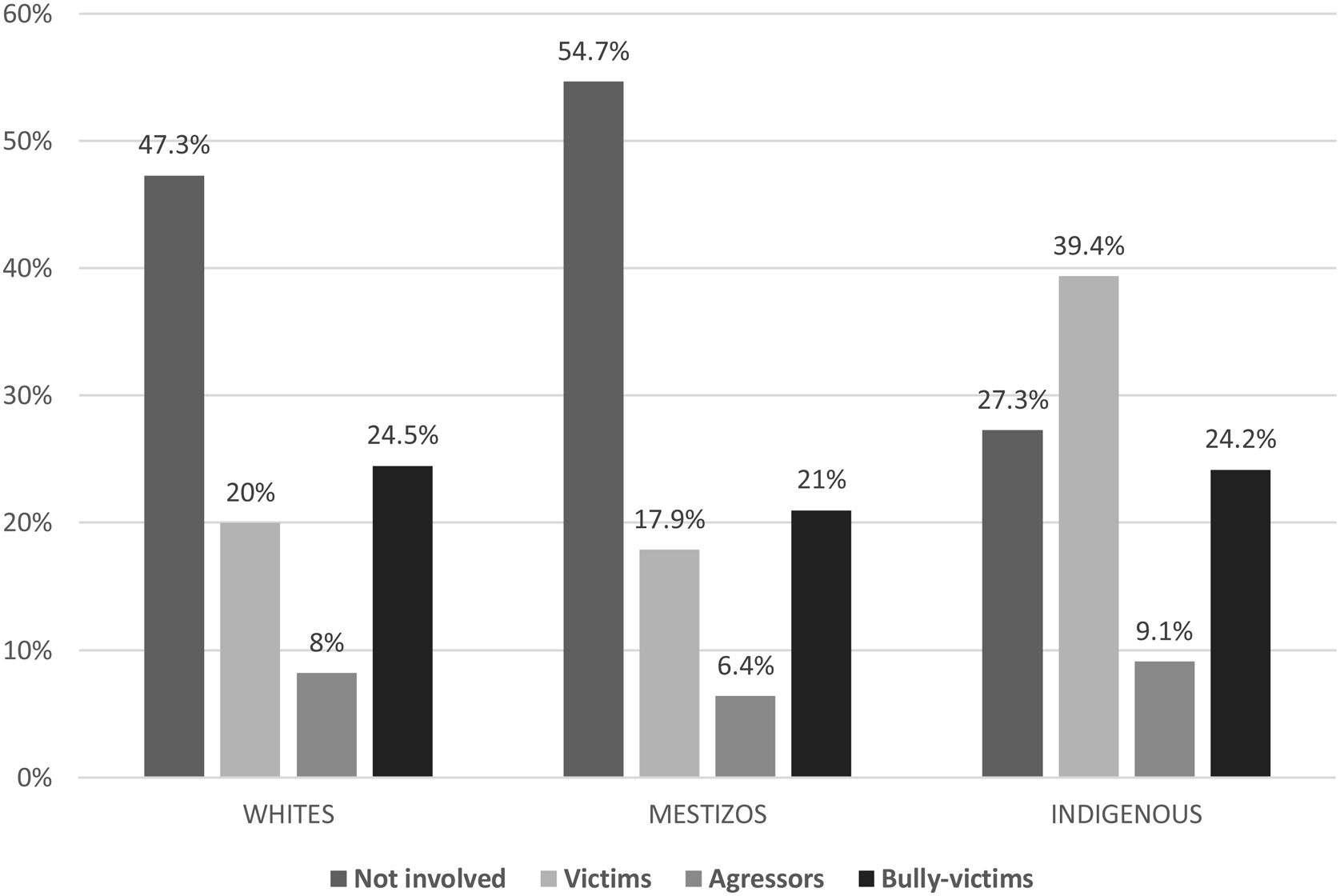

ResultsThe descriptive analysis in Figure 1 shows the percentages involved in ethnic-cultural bullying roles. 48.4% of the participants were involved: 19.4% as ethnic-cultural victims, 6.9% as ethnic-cultural aggressors and 22% as ethnic-cultural bully-victims.

Percentages of students involved in the different roles of ethnic-cultural bullying.

Note. Odds Ratio calculated according to the role. Victims: white-mestizo (OR=1.29, 95% CI=.73 - 2.26*), white-indigenous (OR=.29, 95% CI=.10 - .78*), indigenous-mestizo (OR=4.41, 95% CI=1.81 - 10.72*). Aggressors: white-mestizo (OR=1.46, 95% CI=.65 - 3.30), white-indigenous (OR=.51, 95% CI=.11 - 2.29), indigenous-mestizo (OR=2.82, 95% CI=.72 - 11.08). Bully-victims: white-mestizo (OR=1.35, 95% CI=.79 - 2.28), white-indigenous (OR=.58, 95% CI=.20 - 1.68), indigenous-mestizo (OR=2.3, 95 % CI=.86 -6.18).

Figure 2 shows the level of involvement in the different roles of ethnic-cultural bullying depending on the ethnic-cultural group. Indigenous people are the group most involved, with 72.2%, and are significantly more commonly victimized than the white group (OR=.29, 95% CI=.10 - .78) and the mestizo group (OR=4.41, 95% CI=.10 - .78). %CI=1.81 - 10.72).

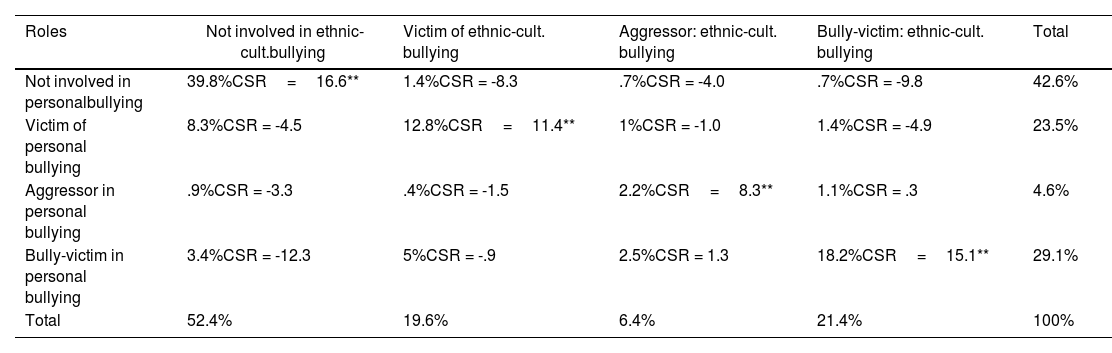

To find the overlap between personal and ethno-cultural bullying roles, a contingency table was created. Table 1 shows how 60.2% of the participants were involved in some type of role in personal or ethnic-cultural bullying. The corrected standardized residuals (CSR) show that exercising a role in personal bullying is related to exercising the same role in ethnic-cultural bullying, and vice versa.

Involvement in the mixed roles of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying

| Roles | Not involved in ethnic-cult.bullying | Victim of ethnic-cult. bullying | Aggressor: ethnic-cult. bullying | Bully-victim: ethnic-cult. bullying | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not involved in personalbullying | 39.8%CSR=16.6** | 1.4%CSR = -8.3 | .7%CSR = -4.0 | .7%CSR = -9.8 | 42.6% |

| Victim of personal bullying | 8.3%CSR = -4.5 | 12.8%CSR=11.4** | 1%CSR = -1.0 | 1.4%CSR = -4.9 | 23.5% |

| Aggressor in personal bullying | .9%CSR = -3.3 | .4%CSR = -1.5 | 2.2%CSR=8.3** | 1.1%CSR = .3 | 4.6% |

| Bully-victim in personal bullying | 3.4%CSR = -12.3 | 5%CSR = -.9 | 2.5%CSR = 1.3 | 18.2%CSR=15.1** | 29.1% |

| Total | 52.4% | 19.6% | 6.4% | 21.4% | 100% |

Chi square (9)=513.48, ** p< 0.01.

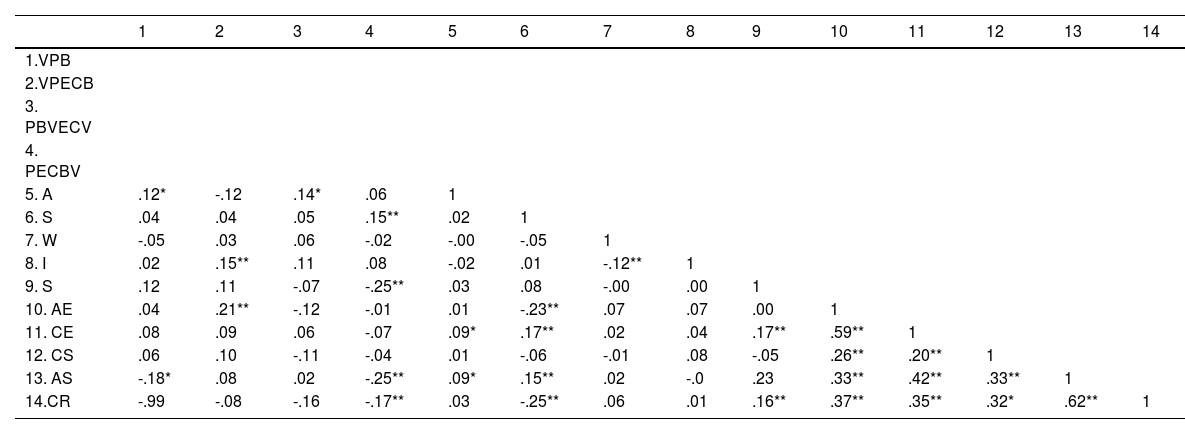

Table 2 shows a correlation analysis between the mixed roles and the study variables. The role of victim of personal bullying (VPB) is related to older age and low assertiveness. The role of victim of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying (VPECB) is related to being indigenous and having a high affective empathy. The role of personal bully-victim and ethnic-cultural victim (PBVECV) is only related to older age. The role of personal and ethnic-cultural buly-victim (PECBV) is related to being male, and having low self-esteem, low assertiveness and low conflict resolution. No multicollinearity was found between the variables.

Correlation of mixed roles with age, sex, ethnic-cultural group, self-esteem, empathy and social skills

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.VPB | ||||||||||||||

| 2.VPECB | ||||||||||||||

| 3. PBVECV | ||||||||||||||

| 4. PECBV | ||||||||||||||

| 5. A | .12* | -.12 | .14* | .06 | 1 | |||||||||

| 6. S | .04 | .04 | .05 | .15** | .02 | 1 | ||||||||

| 7. W | -.05 | .03 | .06 | -.02 | -.00 | -.05 | 1 | |||||||

| 8. I | .02 | .15** | .11 | .08 | -.02 | .01 | -.12** | 1 | ||||||

| 9. S | .12 | .11 | -.07 | -.25** | .03 | .08 | -.00 | .00 | 1 | |||||

| 10. AE | .04 | .21** | -.12 | -.01 | .01 | -.23** | .07 | .07 | .00 | 1 | ||||

| 11. CE | .08 | .09 | .06 | -.07 | .09* | .17** | .02 | .04 | .17** | .59** | 1 | |||

| 12. CS | .06 | .10 | -.11 | -.04 | .01 | -.06 | -.01 | .08 | -.05 | .26** | .20** | 1 | ||

| 13. AS | -.18* | .08 | .02 | -.25** | .09* | .15** | .02 | -.0 | .23 | .33** | .42** | .33** | 1 | |

| 14.CR | -.99 | -.08 | -.16 | -.17** | .03 | -.25** | .06 | .01 | .16** | .37** | .35** | .32* | .62** | 1 |

Note. *p< .05. ** < .01. VPB = Victim of Personal Bullying; VPEC = Victim of Personal and Ethnic-Cultural Bullying; PBVECV = Personal Bully-victim and Ethnic-Cultural Victim; PECBV = Personal and Ethnic-Cultural Bully-victim; A = Age; S = Sex; W = White Ethnic-Cultural Group; I = Indigenous Ethnic-Cultural Group; S = Self-esteem; AE = Affective Empathy; CE = Cognitive Empathy; CS = Communication Skills; AS = Assertiveness; CR = Conflict Resolution. The correlations between roles were calculated by comparing each role with the ‘not-involved’ group, and the number of subjects per analysis corresponds to the total of ‘not-involved’ subjects, plus the corresponding role. The other correlations were made with the total number of subjects. It was not possible to calculate correlations between the roles, because these were exclusive.

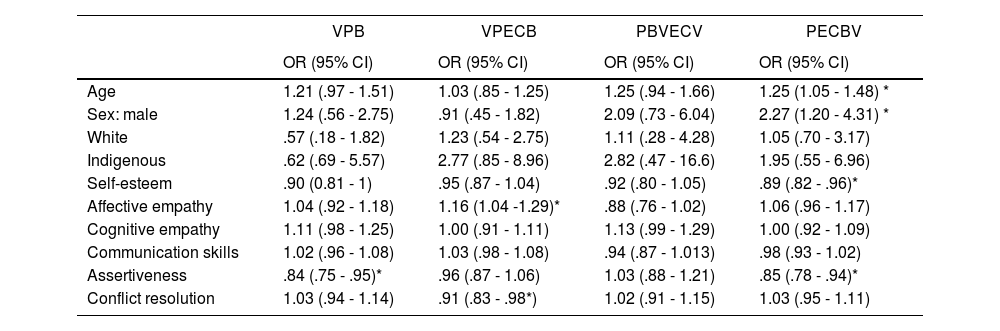

Table 3 shows a multinomial regression analysis, in which age, male sex, ethnic-cultural group, self-esteem, empathy and social skills appear as predictors of the five most prevalent mixed roles (with the ‘not involved’ group included as a reference category). Low assertiveness scores predict being a victim of personal bullying. High scores in affective empathy and low scores in conflict resolution predict the mixed role of victim of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying. No variable predicts the mixed role of personal bully-victim and ethnic-cultural victim. Finally, the mixed role of aggressor-victim of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying is related to older age, being male, and low scores for self-esteem and assertiveness. The model accounts for 26% of the variance, according to the Nagelkerke R2 (Nagalkerke R2=.26).

Multinomial regression with age, sex, ethnic-cultural group, self-esteem, empathy and social skills as predictors of the four most common roles of personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying

| VPB | VPECB | PBVECV | PECBV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | 1.21 (.97 - 1.51) | 1.03 (.85 - 1.25) | 1.25 (.94 - 1.66) | 1.25 (1.05 - 1.48) * |

| Sex: male | 1.24 (.56 - 2.75) | .91 (.45 - 1.82) | 2.09 (.73 - 6.04) | 2.27 (1.20 - 4.31) * |

| White | .57 (.18 - 1.82) | 1.23 (.54 - 2.75) | 1.11 (.28 - 4.28) | 1.05 (.70 - 3.17) |

| Indigenous | .62 (.69 - 5.57) | 2.77 (.85 - 8.96) | 2.82 (.47 - 16.6) | 1.95 (.55 - 6.96) |

| Self-esteem | .90 (0.81 - 1) | .95 (.87 - 1.04) | .92 (.80 - 1.05) | .89 (.82 - .96)* |

| Affective empathy | 1.04 (.92 - 1.18) | 1.16 (1.04 -1.29)* | .88 (.76 - 1.02) | 1.06 (.96 - 1.17) |

| Cognitive empathy | 1.11 (.98 - 1.25) | 1.00 (.91 - 1.11) | 1.13 (.99 - 1.29) | 1.00 (.92 - 1.09) |

| Communication skills | 1.02 (.96 - 1.08) | 1.03 (.98 - 1.08) | .94 (.87 - 1.013) | .98 (.93 - 1.02) |

| Assertiveness | .84 (.75 - .95)* | .96 (.87 - 1.06) | 1.03 (.88 - 1.21) | .85 (.78 - .94)* |

| Conflict resolution | 1.03 (.94 - 1.14) | .91 (.83 - .98*) | 1.02 (.91 - 1.15) | 1.03 (.95 - 1.11) |

Note. The reference category is not involved in any type of bullying; VPB=Victim of Personal Bullying; VPECB=Victim of Personal and Ethnic-Cultural Bullying; PBVECV=Personal Bully-victim and Ethnic-Cultural Victim; PECVA=Personal and Ethnic-Cultural Bully-victim.

This study shows that half of the adolescents in the Peruvian Amazon are involved in ethnic-cultural bullying. This percentage of involvement in ethnic-cultural bullying is double the figure recently observed in Spain using the same instrument and research methodology (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al., 2019). The prevalence of ethnic-cultural bullying in Peru is also higher than levels registered in other more economically-developed countries, such as the US (Gill & Govier, 2023; US Department of Education, 2018). As a conclusion, in the Peruvian Amazon, two out of every five participants classify themselves as ethnic-cultural victims, two out of five are ethnic-cultural bully-victims, and seven out of 100 are ethnic-cultural aggressors. Compared to the situation in Spain (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al., 2019), in the Peruvian Amazon there are twice as many ethnic-cultural victims, two-thirds more ethnic-cultural aggressors-victimized, and twice as many ethnic-cultural aggressors. Based on these initial observations, the first part of the first hypothesis has been corroborated: there is a high prevalence of ethnic-cultural bullying in the Peruvian Amazon. The high level of involvement in ethnic-cultural bullying found could be due to factors such as the lack of development in programs and measures to prevent and alleviate personal bullying (Gaffney et al., 2019) and ethnic-cultural bullying (Earnshaw et al., 2018), as well as the wide ethnic-cultural diversity found in the area, together with the high levels of ethnic-cultural prejudice and violent racist behavior in society and in schools (Dorival-Córdova, 2018; Martínez-Torres et al., 2019; Pazos, 2016).

According to the first hypothesis, it was also expected to find differences in the levels of involvement in ethnic-cultural bullying depending on the ethnic-cultural group, consistent with prevailing prejudices based on social dominance. This study shows how the ethnic-cultural group of white adolescents, even though they are a minority compared to the mestizo group, is not significantly more victimized in ethnic-cultural bullying than the group of mestizo adolescents. However, the ethnic-cultural minority of indigenous adolescents suffers more victimization and greater involvement than white and mestizo groups, with a level of victimization of 39.4% and involvement in victimization and/or aggression of 72.7%. It can be also concluded that the percentage of indigenous ethnic-cultural bullying victims is double that of the mestizo ethnic-cultural victims and white ethnic-cultural victims put together. Additionally, it can be corroborated the existence of differences in the levels of involvement in ethnic-cultural bullying depending on the ethnic-cultural group, which are consistent with the prevailing prejudices based on social dominance (Żemojtel-Piotrowska et al., 2020), characterized here by the positive attributions and idealization of the ethnic-cultural traits of the white group, the dominance of the mestizo group due to its greater social presence, and the negative attributions and rejection towards the indigenous group, which is a highly diverse minority in itself, since it is made up of a wide range of ethnic-cultural identities.

The levels of ethnic-cultural victimization suffered by the indigenous people in the Peruvian Amazon are highly worrying, with even higher rates than those registered in a North American study which found a prevalence of bullying towards indigenous people of 38.6% (Melander et al., 2013). This greater victimization suffered by the indigenous minority group is consistent with the findings of a number of studies (Bjereld et al., 2014; Maynard et al., 2016; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2014; Strohmeier et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2020). These conclusions are also in line with those of the meta-analysis by Vitoroulis and Vaillancourt (2018) which compared the involvement of whites and indigenous people in ethnic-cultural bullying, and concluded that indigenous people are significantly more involved and victimized. The greater discrimination towards this indigenous ethnic-cultural minority group might be exacerbated by racist attitudes and fewer opportunities for development, which give further weight to the imbalance of power between the different ethnic-cultural groups (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al., 2019). Likewise, the high prevalence of victimization towards the indigenous ethnic-cultural group is particularly alarming, with high levels of racism being documented previously in Peruvian studies (Dorival-Córdova, 2018), especially in the Peruvian Amazon, where the discrimination towards the indigenous ethnic-cultural group has been documented (Pazos, 2016). This discriminatory victimization is sometimes perpetuated in schools (Martínez-Torres et al., 2019) and causes unfair rejection both by members of other ethnic-cultural groups and between members of different indigenous groups. This places the multiple indigenous cultures at great risk of disappearance and puts the members of their communities at risk of social exclusion and exposed to greater vulnerability due to uprooting (Martínez-Torres et al., 2019).

According to the second hypothesis, there would be an overlap between personal and ethnic-cultural bullying. The study concludes that the two phenomena do indeed overlap in many ways. Six out of ten participants are involved in both personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying, and being a victim, aggressor and/or bully-victim in personal bullying is related to exercising the same role in ethnic-cultural bullying, and vice versa. The only reference to support these conclusions can be found in a study recently conducted in Spain (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra et al., 2019). These findings in the Peruvian Amazon serve to further the knowledge about the relationship between the roles of these two forms of peer violence, beyond observations made by a few studies on the relationship between being a victim of bullying and being a victim of ethnic-cultural bullying (Benner & Wang, 2017; Cardoso et al., 2018; Monks et al., 2008; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2015, 2014). It is especially worrying that nearly two out of ten adolescents in the Peruvian Amazon recognize themselves in the overlapping role of bully-victim of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying.

It can be also concluded that lower scores for self-esteem predict the mixed role of aggressor-victim of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying. This is in line with the scientific literature, where low levels of self-esteem have been described in victims (Álvarez et al., 2022; Martínez et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2014) and is related to studies where the low self-esteem implies a greater risk of aggression and victimization due to personal bullying (Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2015; Van Geel et al., 2018) and ethnic-cultural victimization (Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2014). This dual involvement in aggression and victimization, together with the high percentage of indigenous people found to be involved in both personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying, and taking into account the work by Veenstra et al. (2010), all lead us to hypothesize that the majority of bully-victims could originally be victims with low self-esteem who are unable to defend themselves effectively. This might encourage them to respond in reprisal to the personal and ethnic-cultural aggression received, fueled by the fact they feel different for belonging to a minority ethnic-cultural group, as has been observed previously in other bully-victims (Goldweber et al., 2013).

Another conclusion is that higher scores in affective empathy predict the dual, mixed role of victim of personal bullying and victim of ethnic-cultural bullying. This finding is a far cry from the negative relationship previously found in the literature between affective and cognitive empathy and victimization (Kokkinos & Kipritsi, 2012). However, it is consistent with the results of a study carried out in Ecuador that uses the same methodology and instruments (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Pantaleón et al., 2019), and also agrees with observations in the scientific literature on personal bullying which highlight the association between high levels of empathy and victimization (Fousiani et al., 2016; Martínez et al., 2020; Trach et al., 2023; Zych, Farrington et al., 2019). This relationship between victimization and empathy seems to reinforce the idea that the role of victim involves greater sensitivity and empathy than other roles (Caravita et al., 2010; Ortega-Ruiz, 2010). It is postulated that the victims of both personal and ethnic-cultural bullying are better able to understand the emotional impact which an attack might have on others and, therefore, would not themselves commit violent and/or discriminatory acts of a personal or ethnic-cultural nature.

In the present study, no significant relationship was found between empathy and aggression. This contrasts with the results of meta-analysis studies that highlight the relationship between empathy and aggression in personal bullying (Zych, Farrington et al., 2019; Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019). One factor which may account for this is that the mechanisms underlying ethnic-cultural bullying could differ somewhat from those involved in personal bullying, with a more important role played by moral disconnection (for instance, perceiving people of other ethnic groups-cultures as less worthy of being treated respectfully). These possible mechanisms should be examined in greater depth in further studies.

As regards social skills, it is clear that low assertiveness predicts the mixed role of personal victim and ethnic-cultural victim, as well as the mixed role of personal aggressor-victimized and ethnic-cultural victim and is related to the role of personal bullying victim. Similarly, low levels of conflict resolution predict the mixed role of personal victim and ethnic-cultural victim and are related to being a personal and ethnic-cultural aggressor-victim. These conclusions are consistent with the previous literature, which reports low levels of social skills as predictors of personal aggression (Jenkins et al., 2017; Nickerson et al., 2008; Pozzoli & Gini, 2010), personal victimization (Jenkins et al., 2017; Kochel et al., 2015) and ethnic-cultural aggression (Vera et al., 2017). When comparing the results with a study that linked social skills with victimization and personal aggression in Spain and Ecuador, similar results were found in Spain but not in Ecuador, where no relationship has been found between these variables (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Pantaleón et al., 2019). It may be that the importance of the different social skills depends on the social and cultural context, but future studies are required to confirm this possibility.

In relation to the ethnic-cultural groups of adolescents studied, it can be concluded that none of the predictions about the most common mixed roles was based on belonging to any of the ethnic-cultural groups studied. However, a significant relationship was found between being indigenous and being a victim of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying. This relationship is in line with studies which have found that being a member of an ethnic-cultural minority group entails a greater risk of involvement in bullying (Llorent et al., 2021, 2016; Maynard et al., 2016; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2020).

Being older and male are factors which are significantly linked to the mixed role of ethnic-cultural and personal aggressor-victim. Similarly, the role of victim of personal bullying and the role of personal aggressor-victimized and ethnic victim are related to being older. These results coincide with Latin American studies which have found that males are more commonly involved (Garaigordobil et al., 2018) and victimized (Zeladita-Huaman et al., 2022), which may be due to the sexist culture prevalent in many areas of Peru and Latin America (Meza, 2016). It also agrees with other Peruvian studies, where a relationship has been found between being older and being a personal bully-victim (Martínez et al., 2020).

The findings of the study also allow us to corroborate the third hypothesis: that relationships exist between low levels of self-esteem, empathy and social skills and a greater involvement in the mixed roles of personal and ethnic-cultural bullying. These findings help to reinforce the observations from a particularly novel set of recent studies which found a relationship between low assertiveness and ethnic-cultural victimization, which further extends the existing scientific literature in this area. Social skills have been shown to play a key role in predicting involvement in personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying.

Based on the scientific evidence provided above, proposals can be made to improve the prevention and alleviation of peer violence in the Peruvian Amazon, as well as possibly in other geographical areas with similar characteristics. Given the considerable overlap detected between personal bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying in this context, it is vital that interventions should focus on the ethnic-cultural diversity of each school and promote greater inclusion. These steps should also be given a holistic perspective, with an action plan and specific measures which are included in the obligatory educational curriculum (Llorent et al., 2021). The psychoeducational prevention and alleviation of bullying, to be truly effective, must start by reducing and eradicating ethnic-cultural prejudices, which serve to support the multiple forms of violence and discrimination among adolescents who perceive each other as ethnically and culturally unequal. These measures must also take the fight against prejudice one step further, by contributing to the development of intercultural coexistence and the inclusion of diversity.

It is also clear from the conclusions obtained that fundamental educational work to promote and develop self-esteem, empathy and social skills should be a key priority in order to improve psychoeducational prevention and palliation programs. In particular, they should stimulate and encourage adolescents to develop a positive self-image (Clarkson et al., 2019; Espelage et al., 2015; Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017), focusing on the elements of identity which are part of belonging to any ethnic-cultural group in order for them, individually, and their community, to grow. It is also vital to recognize the contribution of each adolescent to the roots and cultural knowledge of their native culture, as a key element for them to develop their individual identity, and as a positive asset they should feel proud to share at school and in society. It is vital to eradicate the old, prejudiced idea in schools that the culture of origin of students from ethnic-cultural minority groups is somehow a disadvantage or a handicap. This would help to nurture greater, positive self-esteem among all adolescents of diverse ethnic-cultural origins and contribute to fostering greater intercultural and social coexistence in schools.

Another key element of preventive and palliative programs should be the enhancement of social skills, in particular to promote assertiveness and conflict resolution skills and abilities, which could have a major impact on reducing violence between peers (Avşar & Alkaya, 2017; Heydenberk et al., 2006; Keliat et al., 2015), and improve coping strategies among victims, such as expressing their feelings when they are threatened, and asking for help (Elliott et al., 2019).

This study presents valuable information about ethnic-cultural bullying, the different ethnic-cultural groups and their overlap with personal bullying in an area that has received little attention in the literature. It has been also described the different risk and protective factors, focusing particularly on mixed roles. However, the study also has certain limitations. The sample size could be improved, and future studies with more representative samples are needed to confirm the findings. The study was cross-sectional and the self-reports used were quantitative, which lead to social desirability biases. In the questionnaire on personal bullying, no specific instructions were included for the subjects to exclude bullying for ethnic-cultural reasons from their answers, with the result that some subjects who reported the overlap between ethnic-cultural and personal bullying may, in fact, have been thinking about exactly the same behavior when responding. However, the present results also show clearly diverse roles, where subjects have reported being involved in ethno-cultural bullying, but not in personal bullying, and vice versa. This potential problem of measurement is common throughout the field which focuses on ethnic-cultural bullying (Cardoso et al., 2018; Llorent et al., 2016), and the same problem can occur in studies focused on the overlap (or comparisons) between bullying and cyberbullying, since items referring to bullying, such as having received insults, do not explicitly refer only to face-to-face forms (Del Rey et al., 2012; Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 2015). Future studies should therefore also include other measurement instruments, improve the way of measuring the constructs, and add hetero-reports and quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Similarly, longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the results of this project, which had a cross-sectional design.

Further research is needed into the relationship between bullying and ethnic-cultural bullying, especially in vulnerable and under-resourced areas. Advances in the knowledge of these violent phenomena that occur in a real, face-to-face context can also provide a basis for the progressive study of violent discriminatory phenomena in virtual environments, such as cyberhate or ethnic-cultural cyberbullying. In a similar way, it could be interesting to relate ethnic-cultural bullying to other violent phenomena such as hate speech. To do this, further research focusing on ethnic-cultural differences is required, to reduce racism and discrimination. Scientific evidence should be the basis on which the different educational programs are built, since the more solid the scientific basis, the greater the chances it has of success.

FundingThis work has partially been carried out thanks to a grant from the Cooperation Program of the University of Cordoba. This work was conducted within the framework of the 2023 Program/Project for International Cooperation with Development and Education for Peace and Development, financed by the Cordoba City Council.

This work has been made possible by the support of the Chair of Sustainable Development and Solidarity of the University of Cordoba (Spain) in collaboration under an agreement with the Cordoba City Council.