This study aimed to analyze the mediating effect of motivational climate on the relationship between interpersonal teaching styles and academic self-concept in university Physical Education students, considering gender differences. To achieve this, two complementary studies were conducted. In Study 1, the Motivational Climate in Higher Education Scale was adapted and validated for use in the Mexican University context. In Study 2, a mediation model was evaluated, analyzing how teaching styles (autonomy support and controlling style) influence academic confidence and effort, with motivational climate as a mediating factor. The study followed a cross-sectional design with a sample of 1164 students from the Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Education at the Autonomous University of Baja California. The results showed that autonomy support from teachers positively predicts students’ academic confidence and effort, while the controlling style had no direct effect on these variables. Additionally, gender differences were identified: among male students, task-involving motivational climate mediated the relationship between autonomy support and academic self-concept, whereas among female students, the effect was direct. These findings highlight the importance of promoting learning environments based on autonomy, which foster academic confidence and effort, while avoiding controlling teaching strategies that could negatively impact students’ educational development.

Este estudio analiza el efecto mediador del clima motivacional en la relación entre los estilos interpersonales de enseñanza y el autoconcepto académico en estudiantes universitarios de Educación Física, considerando las diferencias de género. Para ello, se han llevado a cabo dos estudios complementarios. En el Estudio 1, se ha adaptado y validado la Escala de Clima Motivacional en Educación Superior para su aplicación en el contexto universitario mexicano. En el Estudio 2, se ha evaluado un modelo de mediación, analizando cómo los estilos docentes (apoyo a la autonomía y estilo controlador) influyen en la confianza y el esfuerzo académico de los estudiantes, con la mediación del clima motivacional. El estudio adopta un diseño transversal con una muestra de 1.164 estudiantes de la Licenciatura en Educación Física en la Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. Los resultados evidencian que el apoyo a la autonomía del docente predice positivamente la confianza y el esfuerzo académico de los estudiantes, mientras que el estilo controlador no muestra un efecto directo sobre estas variables. Además, se han identificado diferencias de género: en los hombres, el clima motivacional orientado a la tarea actúa como mediador entre el apoyo a la autonomía y el autoconcepto académico, mientras que en las mujeres este efecto ha sido directo. Estos hallazgos subrayan la importancia de promover entornos de aprendizaje basados en la autonomía, que fomenten la confianza y el esfuerzo académico, evitando estrategias docentes controladoras que puedan afectar negativamente el desarrollo educativo del alumnado.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) maintains that Latin America is one of the most unequal regions on the planet across multiple domains, including educational disparities in terms of gender (United Nations Development Programme, 2021). Within the Mexican Educational System, education is delivered through a masculinized framework that stereotypes learning according to gender (Lechuga et al., 2018), so inequalities in education are persistent and deeply rooted in the different ways in which knowledge and behaviors are generated, heavily influenced by learning environments and teaching styles (Rodríguez & Ceballos, 2022). Said disparities worsen for certain specific fields, including Physical Education (Baños, 2021; Cuenca-Soto et al., 2024). In this sense, learning environments and the teachers’ interpersonal styles may condition variables such as academic self-concept and behavior among Mexican university students (Espinoza-Gutiérrez et al., 2024), understanding that past learning experiences and interactions with teachers and peers are critical for enhancing academic confidence and effort (Granero-Gallegos, Hortigüela-Alcalá et al., 2021; Shavelson et al., 1976).

Academic self-conceptAccording to Rojo-Ramos et al. (2024), academic self-concept refers to students’ perceptions of their own capabilities in learning-related tasks. This conceptualization is rooted in the multidimensional and hierarchical Self-Concept Theory proposed by Shavelson et al. (1976). As a mental representation of students’ academic abilities, it involves both self-description and self-assessment aspects (Brunner et al., 2009), with academic effort and confidence serving as two core pillars in the development of academic self-concept (Granero-Gallegos, Baena-Extremera et al., 2021). Academic confidence refers to the belief that an individual holds in their ability to solve assigned learning tasks to achieve educational goals (Chang et al., 2022). Academic effort is defined as the mental strength that a student must uphold consistently throughout their educational journey (D’Eon & Yasinian, 2022). Both academic confidence and academic effort are considered critical factors in adapting to university demands, improving academic performance, and raising future employability chances (Chang et al., 2022; Tolentino et al., 2019). Conversely, low academic confidence and poor academic effort can limit learning, reduce academic performance and expectations, and increase the likelihood of academic dropout (Demanet & Van Houtte, 2019; Rodríguez-Rodríguez & Guzmán, 2019). Although academic self-concept is a multidimensional construct, the present study focuses on confidence and effort because these two dimensions have been consistently identified in the literature as key predictors of motivation, persistence, and academic adjustment in university settings (Chang et al., 2022; Granero-Gallegos, Baena-Extremera et al., 2021; Santiago, 2024).

In this context, Santiago (2024) highlights the importance of developing academic confidence and effort to prevent Mexican university students from dropping out. Thus, academic self-concept may be partly a consequence of socio-contextual environments (Marsh et al., 2018), with the teachers’ interpersonal styles identified as a key factor in modifying student behavioral patterns (Ryan & Deci, 2020). However, no published studies have analyzed the actual influence of teaching styles on student behaviors in the Mexican university context.

Teacher interpersonal styleTeacher interpersonal style refers to the interpersonal and behavioral tone teachers employ to engage students in their own learning process (Reeve et al., 2019; Reeve et al., 2018) according to Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which posits at least two teaching styles: autonomy-supportive and controlling (Ryan & Deci, 2020). The autonomy-supportive style is characterized by developing teaching strategies aligned with student interests, providing a rationale for assigned tasks, and giving opportunities for choice (Reeve et al., 2022). Conversely, a controlling style imposes teacher-driven strategies that condition student thoughts, behaviors, and emotions, as previously described by the same authors. International scientific literature linking teacher interpersonal styles to academic confidence and effort in university students is scarce and contradictory. On the one hand, Granero-Gallegos et al. (2022) found that only the controlling style negatively predicts academic confidence, with no predictive effect from autonomy support and not having examined the academic effort dimension. On the other hand, Rubio-Valdivia et al. (2022) found that autonomy support positively predicts academic confidence and effort, with no predictive effect from the controlling style. Recently, Espinoza-Gutiérrez et al. (2024) also demonstrated that autonomy support predicts academic self-concept in Mexican university students, with no predictive effect from the controlling style and not having analyzed the academic confidence and effort subdimensions.

To thoroughly analyze social and interactional environments in learning contexts, Duda (2013) proposed integrating SDT with a detailed hierarchical conceptualization of the main motivational climates (e.g., task-involving and ego-involving climates) from Achievement Goal Theory (AGT; Ames, 1992). Recent studies have thus explored the interaction between SDT and AGT in university students (Granero-Gallegos, Hortigüela-Alcalá et al., 2021; Granero-Gallegos, Baena-Extremera et al., 2023, López-García et al., 2022; Moreno-Murcia et al., 2018). However, no studies have examined this relationship in the Mexican university context.

Motivational climateAchievement Goal Theory (AGT; Ames, 1992) analyses educational achievement environments according to student dispositional factors and learning motivational climates. The importance of the learning climates created by the teacher in the classroom has been greatly emphasized since these could determine the academic success or failure of the students (Ntoumanis & Biddle, 1999). According to authors such as Duda and Appleton (2016), task-involving climates are characterized by taking into account student opinions and preferences, establishing successful interpersonal relationships and intrapersonal learning criteria based on skill development and personal effort, which translate into students feeling valued and cared for, and therefore more confident. Conversely, ego-involving climates tend to condition the student’s thoughts and behavior through prescribed control, establishing interpersonal success criteria based on differential treatment to boast superiority by rewarding achievements and punishing errors.

These learning climates have been analyzed in middle school (secondary) Physical Education classes, yielding truly concerning results: Mexican secondary teachers employ ego-involving climates more frequently than task-involving ones. Ego-involving motivational climates in Mexican secondary education correlates with increased classroom boredom (Baños & Arrayales, 2020), more disruptive behaviors (Baños, 2021), and sedentary lifestyles, as students disregard physical activity during their leisure time (Baños, Ruiz-Juan et al., 2018). However, no currently available scales measure motivational climate in the Mexican university context. Therefore, adapting and validating an instrument that analyses learning environments in higher education could help to improve learning processes in Mexican universities.

Gender differencesGender-neutral teaching styles and learning environments may positively impact the learning processes and academic performance of future Physical Education teachers (Stein et al., 2014). However, studies addressing this aspect in Mexican university students, regardless of their study course, are scarce. This shortage is particularly relevant for Mexican women, who face ongoing educational inequalities compared to men (Rodríguez & Ceballos, 2022). International scientific literature has shown that, in general, females perceive task-involving (mastery) climates more frequently, while males report ego-involving (performance) climates the most, both among adolescents (Baños, 2021; Olivier et al., 2024; van Hek et al., 2018) and university students (D’Lima et al., 2014), with fewer published studies for the latter. Regarding teaching styles, available studies are scarce and contradictory: while male university students perceive more controlling styles (Huéscar-Hernández et al., 2017), female secondary students report higher perceived control from teachers (De Meyer et al., 2014). Additionally, female university students tend to report feeling less confident in their capabilities (Martín Antón et al., 2022) but exhibit greater academic effort compared to males (Espinoza & Albornoz, 2023). These findings underscore the need to further explore gender differences in teaching and learning environments to remediate gaps in the Mexican education context.

The present studyAfter reviewing the relevant literature, it is noteworthy that adapting and validating the motivational climate scale for higher education to the Mexican context will enable a more precise assessment, acknowledging the cultural, pedagogical, and structural features of learning environments in Mexico. This has the potential not only to enhance the quality of educational research, but also to provide a valuable tool for optimizing pedagogical interventions and fostering a more motivating and effective academic environment. Moreover, no published studies on Mexican university students are known to have analyzed the potential differences in teacher-student interactions due to gender, which may translate into differentiated implications for student confidence and effort. Therefore, researching motivational educational needs according to gender and their impact on academic confidence and effort brings an opportunity to improve the educational process and promote a more individualized, inclusive and equal environment. Given these considerations, this paper has been divided into two research studies.

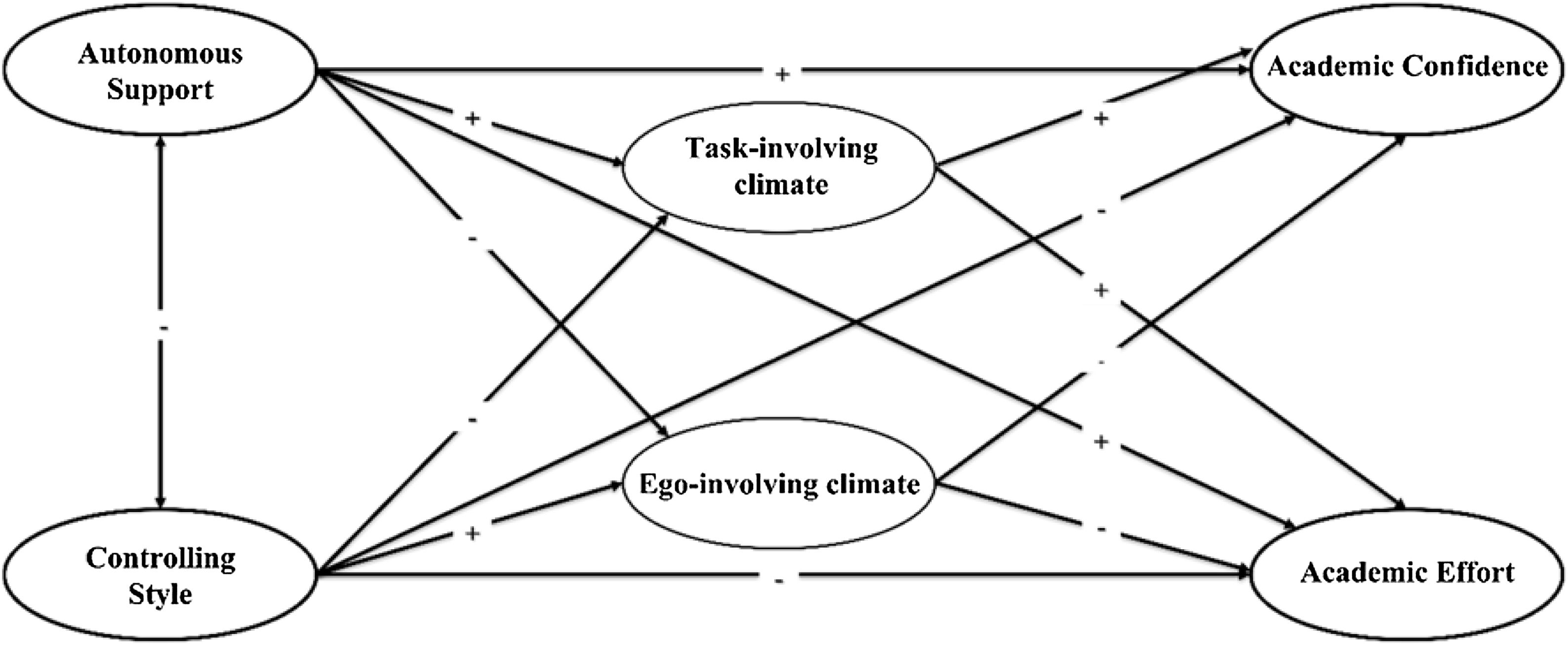

In study-1, the objective was to analyze the psychometric properties of the Motivational Climate Scale adapted to the Mexican university context. In study-2, the objective was to analyze the mediating effect of the academic motivational climate (AMC) between teacher interpersonal style and academic confidence and effort in Mexican university students, taking gender into account. The hypothesized model of this research is shown in Figure 1. This study has adhered to the guidelines established for reporting observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) (Von Elm et al., 2008) for the description of the study.

Study 1MethodDesign and participantsThe research design was descriptive, cross-sectional and observational. Participants were selected from students enrolled in the Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Activity and Sport at the Faculty of Sports, Tijuana Campus, Autonomous University of Baja California. Inclusion criteria required enrollment in the aforementioned study course and regular class attendance; exclusion criteria included refusal to give consent for the use of their data in this study and submission of an incomplete data collection form. An a priori analysis was performed using the Free Statistics Calculator v. 4.0 software (Soper, 2024), which calculated a minimum of 572 subjects needed to detect effect sizes f2 = 0.18 with a statistical power of .99 and a significance level α = .05 in a structural equation model (SEM) with two latent variables and eleven observed variables. A total of 577 students (28.3% female; 71.2% male; 0.5% other) participated in the study from the Faculty of Sports, Tijuana Campus of the Autonomous University of Baja California, aged between 17 and 50 years old (M = 21.38, SD = 3.45). The total study population (N), students of the Faculty of Sports, Tijuana Campus of the Autonomous University of Baja California, is 756 (per institutional transparency records), yielding a 76% participation rate. The sample was therefore deemed representative with a 99% confidence level and a 2.62% margin of error. The sample size met Carretero-Dios and Pérez’s (2005) requirement of at least ten participants per item to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). There were no lost values in the responses included in the study. Apart from the total sample, four questionnaires were discarded due to the lack of corresponding consent to participate in the study.

InstrumentsMotivational Climate in Education (MCE). The scale by Granero-Gallegos and Carrasco-Poyatos (2020), from the original version by Stornes and Bru (2011), was adapted to the Mexican university context. The scale is composed of two correlated factors to measure the task-involving climate (four items; e.g., “The professor expects us to learn new skills and obtain new knowledge and abilities”) and the ego-involving climate (three items; e.g., “The professor pays more attention to successful students”) as perceived by students. A Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree was used to collect responses.

ProcedureThe research objective was first presented during a meeting with the three deputy directors and the general director of the Faculty of Sports, Tijuana Campus of the Autonomous University of Baja California. Upon receiving approval to conduct the study, an in-person meeting with the participants was held in the institution’s computer room in March 2022. During this session, participants were taught how to fill out the online forms and informed of the importance of the study and that their responses were confidential. Students were asked to be honest, as there were no “right” or “wrong” answers, and reminded that they were free to withdraw from participation at any time if they so desired. All participants gave their prior consent for their responses to be included in the study. The research protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Almeria (Ref:UALBIO2023/001).

Risk of biasThis study employed a convenience sampling method, which means that participants were not randomly selected. Additionally, blinding was maintained between participants and the researchers responsible for data processing and analysis. To minimize selection bias, all communication with the students was conducted face-to-face, and participation was entirely voluntary.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistical data of each item were calculated using SPSS 29 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA), and the original factorial structure of the MCE scale was assessed by conducting a CFA with AMOS 29. In terms of the CFA, Mardia’s coefficient values were considered, and analyses were conducted using the maximum likelihood (ML) method and the 5000-iterations bootstrapping (Kline, 2023). For the analysis, values of the standardized regression weights > .50 were deemed acceptable (Hair et al., 2019). The CFA was conducted observing different goodness-of-fit indices: χ2/df ratio (chi-squared/degrees of freedom), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker–Lewis Index), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) with an interval of confidence (IC) of 90%, and SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual). For the χ2/df ratio, values <2.0 were considered excellent (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019), whereas < 5.0 were deemed acceptable (Hu & Bentler, 1999); for CFI and TLI, values between .90 and .95 were acceptable, and values > .95 were excellent; for RMSEA, values < .06 were deemed excellent, and < .10 were marginally acceptable; and for SRMR, values < .60 were excellent and < .08 were acceptable. The reliability of each scale was assessed using different parameters: Cronbach’s alpha (α), McDonald’s omega (ω), and AVE (Average Variance Extracted) were estimated. Reliability values > .70 and AVE > .50 were deemed acceptable (Hair et al., 2019).

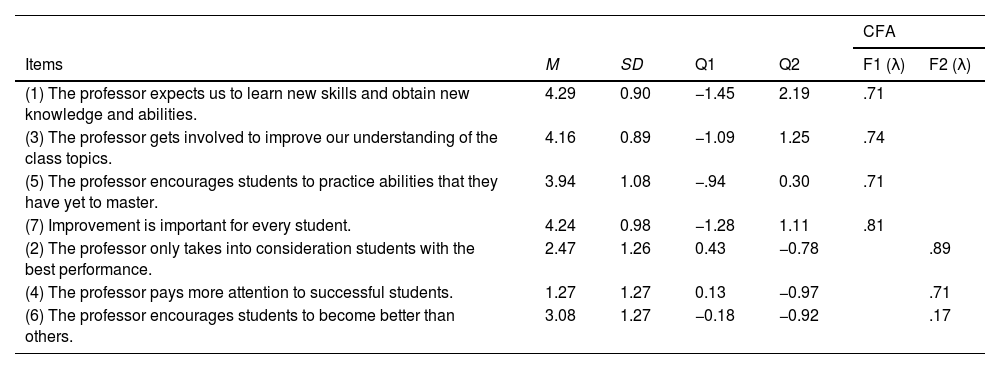

ResultsDescriptive analysis, factorial structure and reliabilityTable 1 shows the descriptive statistical data of the items and the CFA results with the 7 items and two correlated factors of the MCE scale, which, in general, yielded acceptable goodness-of-fit indices: χ2/df = 5.86, p = .000; CFI = .948; TLI = .917; RMSEA = .092 (90%CI = .073; .112); SRMR = .078. However, item 6 had a standardized factorial load of .17, lower than the > .50 value recommended by Hair et al. (2019). After discarding item 6, goodness-of-fit values of the model were excellent: χ2/df = 1.27, p = .258; CFI = .998; TLI = .996; RMSEA = .022 (90%CI = .000;.059); SRMR = .017. Reliability values were: task-involving climate (F1), ω = .83, α = .83, AVE = .55; ego-involving climate (F2), ω = .79, α = .78, AVE = .66. Factor correlation was -.16.

Descriptive statistical data of the items and confirmatory factor analysis of Motivational Climate Education

| CFA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | M | SD | Q1 | Q2 | F1 (λ) | F2 (λ) |

| (1) The professor expects us to learn new skills and obtain new knowledge and abilities. | 4.29 | 0.90 | −1.45 | 2.19 | .71 | |

| (3) The professor gets involved to improve our understanding of the class topics. | 4.16 | 0.89 | −1.09 | 1.25 | .74 | |

| (5) The professor encourages students to practice abilities that they have yet to master. | 3.94 | 1.08 | −.94 | 0.30 | .71 | |

| (7) Improvement is important for every student. | 4.24 | 0.98 | −1.28 | 1.11 | .81 | |

| (2) The professor only takes into consideration students with the best performance. | 2.47 | 1.26 | 0.43 | −0.78 | .89 | |

| (4) The professor pays more attention to successful students. | 1.27 | 1.27 | 0.13 | −0.97 | .71 | |

| (6) The professor encourages students to become better than others. | 3.08 | 1.27 | −0.18 | −0.92 | .17 | |

Note. M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation; Q1 = Asymmetry; Q2 = Kurtosis; F1 = task-involving (mastery) climate; F2 = ego-involving (performance) climate; λ = Standardized factorial loads.

The research design was descriptive, cross-sectional and observational. The selected sample was composed of students enrolled in the Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Activity and Sport at the Faculty of Sports of the three campuses of the Autonomous University of Baja California (Ensenada, Mexicali and Tijuana). Inclusion criteria required enrollment in the aforementioned study course at said university; exclusion criteria included refusal to consent for the use of their data in this study and submission of an incomplete data collection form. An a priori analysis was performed to determine the necessary sample size using a structural equation model (SEM) comprising six latent variables and 23 observable variables. This analysis was conducted using the Free Statistics Calculator v. 4.0 software (Soper, 2024), which calculated a minimum of 1164 subjects needed to detect effect sizes f2 = .166 with a statistical power of .99 and a significance level α = .05 in a structural equation model (SEM) with six latent variables and 23 observed variables. A total of 1164 students participated in the study (30.0% female; 69.6% male; 0.4% other) from the three campuses of the Faculty of Sports of the Autonomous University of Baja California (19.8% Ensenada Campus; 30.7% Tijuana Campus; 49.6% Tijuana Campus) aged between 17 and 50 years old (M = 21.21, SD = 3.26). There were no lost values in the responses included in the study. Apart from the total sample, 29 questionnaires were discarded because they were not filled correctly and 14 because participants did not give their consent.

InstrumentsInterpersonal Teaching Style in Higher Education (Estilo Interpersonal Docente en Educación Superior, EIDES). The scale used was adapted to the Mexican context by Espinoza-Gutiérrez et al. (2024) and validated in Spanish by Granero-Gallegos, Hortigüela-Alcalá et al. (2021). The scale is composed of two correlated factors to measure the perception that students have of their teachers’ support of autonomy (five items, e.g., “My professor thinks it is important that our participation during class is truly self-motivated”) and their perception of their teachers’ controlling style (six items, e.g., “My professor pays less attention to students they don’t like”). Responses were collected using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree.

Motivational Climate in Education (MCE). Described in study-1.

Academic Self-Concept (ASC). The scale used was an adaptation to the Mexican context by Espinoza-Gutiérrez et al. (2024) validated in Spanish by Granero-Gallegos, Baena-Extremera et al. (2021). The scale is composed of two correlated factors to measure academic effort (three items; e.g., “I study a lot for my exams”) and academic confidence (three items; e.g., “If I work hard I think that I can get better grades”) of the students. Responses were collected using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree.

ProcedureSame procedure as study-1.

Risk of BiasSame as study-1.

Statistical analysisA descriptive and correlation analysis of the different variables was conducted. Because factorial invariance of the MCS scale has not been demonstrated in the Mexican context, the invariance of the MCE across sexes was tested using MLR estimation. Four progressively more restrictive models were run for each of the two factors: (1) configural invariance; (2) weak invariance (i.e., invariance of factor loadings/cross-loadings); (3) strong measurement invariance (i.e., invariance of factor loadings/cross-loadings and intercepts); and (4) strict invariance (i.e., invariance of factor loadings/cross-loadings, intercepts and uniqueness). Regarding measurement invariance, nested models were compared considering changes (Δ) in goodness-of-fit indices (i.e., increases in RMSEA of at least .015 or decreases in CFI and TLI of at least .010 indicate a lack of invariance) (Chen, 2007).Due to the lack of sample normality of the variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was performed to analyze differences (pairwise contrasts) according to gender (grouping variable). These analyses were performed using SPSS 29 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

The factor model of each instrument was evaluated separately by conducting a CFA using the ML method and the 5000-iteration bootstrapping procedure (Kline, 2023) using AMOS 29. The same set of fitness indices from study-1 was used for the CFA (χ2/df, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, SRMR). As in study-1, reliability for each scale was calculated using three parameters: α, ω, and AVE. Finally, the hypothesized predictive relationships of the teacher’s interpersonal style on the academic self-concept with mediation of the learning climate involving performance and efficiency were verified using an SEM model with latent variables. The students’ campuses were used as covariates. The fit indices referred to above (χ2/df, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, SRMR) were used to evaluate the SEM fit. Since the results suggested non-normality of the data (Mardia’s coefficient = 122.30), the ML method with the bootstrapping procedure for 5000 resamples (Kline, 2023) was used. Direct and indirect effects were assessed according to Shrout and Bolger (2002), so indirect effects (i.e., mediated) and their 95% IC were estimated using the bootstrapping technique. The indirect effect was deemed significant (p < .05) if its IC 95% did not include the value zero. In addition, R2 was used for effect sizes (ES) to improve results interpretation, as it estimated the degree of influence by quantifying the variance percentage of the dependent variable explained by the predictors (Domínguez-Lara, 2017). Effect size cut-off points were: .02 (small), .13 (medium) and .26 (large) (Cohen, 1992). Furthermore, intervals of confidence (IC 95%) were calculated to ensure that no R2 value was < .02, the minimum value required for its interpretation.

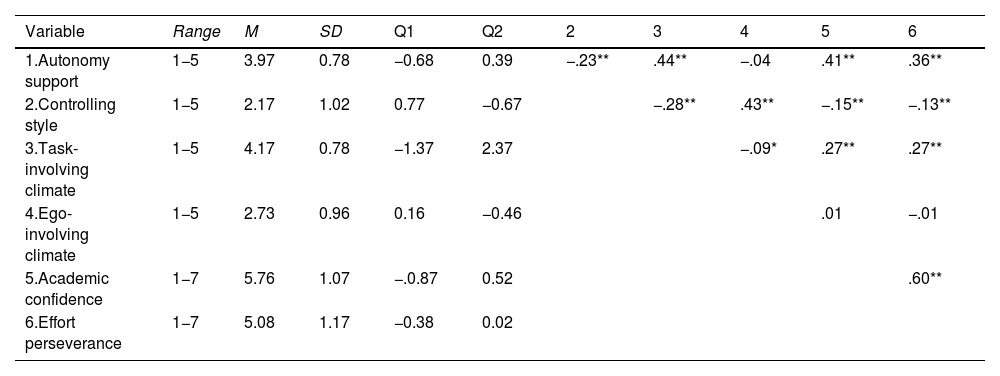

ResultsPreliminary resultsTable 2 shows the descriptive statistical data and correlations between the variables included in the study.

Descriptive statistical data and correlations between variables

| Variable | Range | M | SD | Q1 | Q2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Autonomy support | 1−5 | 3.97 | 0.78 | −0.68 | 0.39 | −.23** | .44** | −.04 | .41** | .36** |

| 2.Controlling style | 1−5 | 2.17 | 1.02 | 0.77 | −0.67 | −.28** | .43** | −.15** | −.13** | |

| 3.Task-involving climate | 1−5 | 4.17 | 0.78 | −1.37 | 2.37 | −.09* | .27** | .27** | ||

| 4.Ego-involving climate | 1−5 | 2.73 | 0.96 | 0.16 | −0.46 | .01 | −.01 | |||

| 5.Academic confidence | 1−7 | 5.76 | 1.07 | −.0.87 | 0.52 | .60** | ||||

| 6.Effort perseverance | 1−7 | 5.08 | 1.17 | −0.38 | 0.02 |

Note. **The correlation is significant at level .01; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; Q1 = Asymmetry; Q2 = Kurtosis.

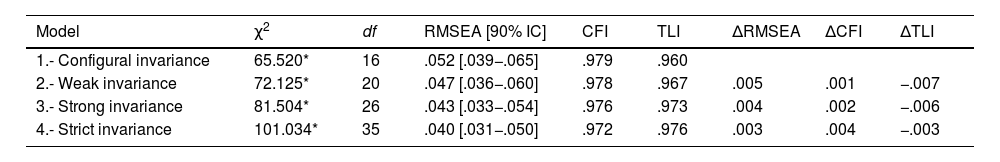

MCE invariance was analyzed according to gender (i.e., male = 810, female = 349) based on the CFA model (results shown in Table 3). It is worth mentioning that the EID and ASC scales have been shown to be invariant for Mexican university students (Espinoza-Gutiérrez et al., 2024). Starting with a configural invariance model (M0), invariance restrictions were progressively added to factor loadings (i.e., weak invariance, M1), intercepts (i.e., strong invariance, M2), and residual variances (i.e., strict invariance). The values of these restrictive models were acceptable, except for strict invariance, as the CFI and TLI results were outside the cut-off values. None of the invariance models exceeded the recommendations for RMSEA (Δ > .015), CFI (Δ > .01), and TLI (Δ > .01), see Table 3.

Invariance test across genders for the Motivational Climate Education Scale

| Model | χ2 | df | RMSEA [90% IC] | CFI | TLI | ΔRMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔTLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.- Configural invariance | 65.520* | 16 | .052 [.039−.065] | .979 | .960 | |||

| 2.- Weak invariance | 72.125* | 20 | .047 [.036−.060] | .978 | .967 | .005 | .001 | −.007 |

| 3.- Strong invariance | 81.504* | 26 | .043 [.033−.054] | .976 | .973 | .004 | .002 | −.006 |

| 4.- Strict invariance | 101.034* | 35 | .040 [.031−.050] | .972 | .976 | .003 | .004 | −.003 |

Note. χ2 = Chi square; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; 90%CI = 90% confidence interval of the RMSEA; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; *p < .05.

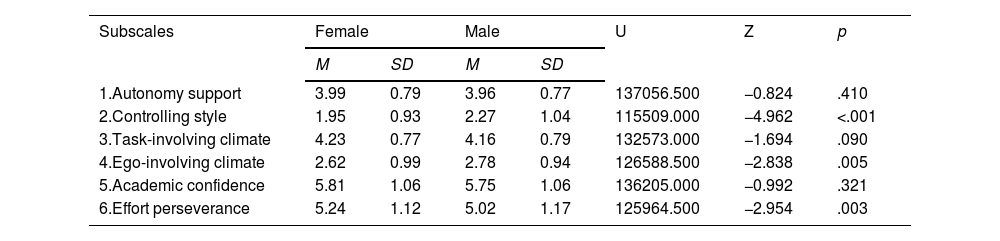

After confirming that the data in this study were nonparametric, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze whether there were differences according to gender (see Table 4). Significant differences were found in three of the research variables. Males presented higher levels of controlling style and ego-involving climate, while females obtained higher scores in effort perseverance.

Results according to gender

| Subscales | Female | Male | U | Z | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| 1.Autonomy support | 3.99 | 0.79 | 3.96 | 0.77 | 137056.500 | −0.824 | .410 |

| 2.Controlling style | 1.95 | 0.93 | 2.27 | 1.04 | 115509.000 | −4.962 | <.001 |

| 3.Task-involving climate | 4.23 | 0.77 | 4.16 | 0.79 | 132573.000 | −1.694 | .090 |

| 4.Ego-involving climate | 2.62 | 0.99 | 2.78 | 0.94 | 126588.500 | −2.838 | .005 |

| 5.Academic confidence | 5.81 | 1.06 | 5.75 | 1.06 | 136205.000 | −0.992 | .321 |

| 6.Effort perseverance | 5.24 | 1.12 | 5.02 | 1.17 | 125964.500 | −2.954 | .003 |

Note. M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; U = Mann-Whitney U test; Z = Kurtosis.

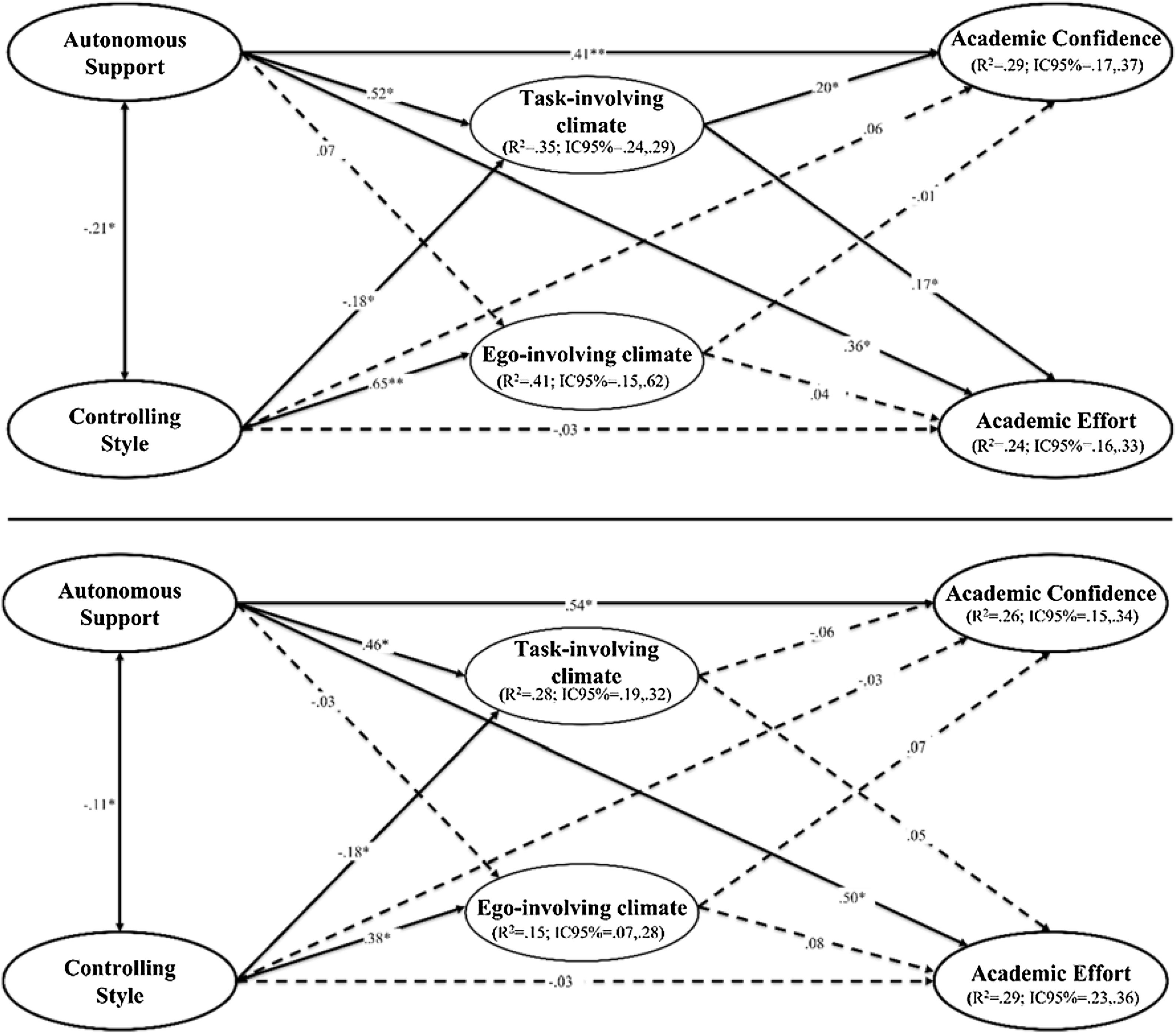

Because significant differences were found according to the gender variable in three of the research variables (see Table 4), a multigroup (i.e., males, females) structural equation analysis with latent variables (Figure 2) was carried out to study the effect of the perception of the interpersonal teaching style (autonomy support and controlling style) on academic self-concept (confidence and effort) mediated by the motivational climate (task-involving climate and ego-involving climate). The model was controlled by the students’ “campus of origin” variable. The SEM yielded adequate fit values: χ2/df = 2.40, p < .001; CFI = .93; TLI = .92; RMSEA = .035(90%CI = .032; .037; pclose = 1.000), SRMR = .054. As shown in Figure 2, the males’ SEM achieved an explained variance of 41% for ego-involving climate, 35% for task-involving climate, 29% for academic confidence and 24% for effort perseverance. In the female group, the model reached an explained variance of 29% for persistence to effort, 28% for task-involving climate, 26% for confidence and 15% for ego-involving climate.

Predictive associations of the interpersonal teaching style with the academic self-concept mediated by the motivational climate in males (above) and females (below).

Note. The 95% CIBC is reported in parentheses **p < .01. *p < .05. R2 = Explained variance; CI = Confidence interval. The dotted arrows represent non-significant relationships.

As can be seen in Figure 2, there is a direct, positive and significant relationship between autonomy support and the two academic self-concept variables (confidence, effort), although the relationship is stronger among females in both cases. In neither model is the direct relationship between autonomy support and ego-involving climate significant, while the direct relationship between autonomy support and task-involving climate is positive and significant in both groups (males, females), although slightly higher among males. On the other hand, the controlling style does not significantly predict confidence or effort in either group, while it significantly and negatively predicts task-involving climate and positively predicts ego-involving climate, with higher values among males for the latter. Concerning the direct and significant relationships of the motivational climate variables, only task-involving climate is positively and significantly related to confidence and effort in the male model, while these relationships are not significant for females. Thus, it is noteworthy that only among males does task-involving climate have a positive and significant mediating effect between the interpersonal teaching style and academic self-concept variables (i.e., confidence and effort). Among males, task-involving climate has significant indirect effects between autonomy support and academic confidence (males, β = .10; 95%CI = .05, .14; p = .035) and effort perseverance (males, β = .09; 95%CI = .02, .12; p = .006), also increasing the total effect among these variables (confidence, β = .51; 95%CI = .37, .61; p < .001; effort, β = .44; 95%CI = .32, .53; p < .001). It is thus demonstrated that, among females, confidence and effort only improve when perceiving autonomy support from the teacher, whereas, among males, this predictive effect is enhanced by the mediation of a task-involving climate in the classroom.

DiscussionThe objective of study-1 was to analyze the psychometric properties of the AMC scale adapted to Mexican university students, while study-2 examined its mediating effect between interpersonal teaching style and academic confidence and effort, considering gender. This research contributes to the literature by validating the AMC scale for the Mexican university context, with similar and acceptable fit indices to the Spanish version in terms of validity and reliability (Granero-Gallegos & Carrasco-Poyatos, 2020). However, it is probable that the cultural equivalence of the removed item from the ego-involving climate was not fully achieved in the Spanish adaptation for the Mexican context. Therefore, future research should review and adjust this item to ensure it reliably and validly represents the construct of performance motivational climate. This instrument can support future research on improving academic well-being through teachers and classroom environments (Hoyo-Guillot & Ruiz-Montero, 2023) and potentially help reduce the high dropout rate among Mexican university students (Álvarez-Pérez & López-Aguilar, 2021).

Study-2 highlights the importance of considering student gender, as teachers' interpersonal style and classroom climate may influence academic confidence and perseverance differently in males and females. The results show that male students reported higher perceptions of their teachers’ controlling style and performance-oriented motivational climates. Similar findings were reported by D’Lima et al. (2014) in ego-involving climates and by Huéscar-Hernández et al. (2017) regarding controlling styles. This may be explained by the higher number of male students, leading professors to assume that ego-involving climates are more motivating for males, fostering competitiveness and producing gender-based differences in learning experiences (Baños, Ortiz-Camacho et al., 2018). Such environments may reinforce stereotypical gender roles, resulting in differences in academic confidence and effort (Stein et al., 2014). Teachers may therefore use more controlling styles that encourage competition through rewards and punishments, expecting students to work harder (Baños et al., 2017), but this can negatively affect motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2020) or even lead to psychosomatic health problems (Bergh & Giota, 2022). In contrast, female students reported significantly higher academic effort, possibly due to the persistent patriarchal structure in Mexico that forces women to work harder to achieve equal outcomes (Rodríguez & Ceballos, 2022), consistent with Deveci’s (2018) findings.

The SEM analysis involved two models, one for males and one for females, which is especially relevant as teachers may impact student motivation differently depending on the academic discipline (Granero-Gallegos, López-García et al., 2023a, 2023b). However, we have not found prior studies offering gender-differentiated results, making this one of the main contributions of the current research.

SEM results showed that autonomy support positively predicted academic confidence and effort for both genders, with a stronger effect in females, who appear to have a greater need to feel supported in their autonomy to enhance these outcomes. However, only in the male model did task-involving climate serve as a mediating variable between teaching style and academic results. This indicates that, beyond autonomy support, male students also require mastery-oriented classroom climates to strengthen their confidence and effort.

Although we did not find previous studies examining this mediation model with gender differences, other research confirms the importance of motivational climate as a mediator between teaching styles and both cognitive (Jiang & Zhang, 2021) and behavioral outcomes (Granero-Gallegos, Hortigüela-Alcalá et al., 2021; López-García et al., 2022) in the university context. This supports the idea that academic confidence and effort are influenced by learning experiences and teacher interactions (Pekrun & Stephens, 2015; Shavelson et al., 1976). Thus, autonomy-supportive professors can create environments aimed at developing students’ skills and mastery (Manzano-Sánchez et al., 2023), and they may also be those with stronger pedagogical resources and higher teaching efficacy (Rubie‐Davies et al., 2012).

Controlling style negatively predicted task-involving climate and positively predicted ego-involving climate in both genders, with a stronger association in males. These findings align with previous literature (Barlow & McCann, 2019; Granero-Gallegos, Hortigüela-Alcalá et al., 2021; López-García et al., 2022). The stronger association of ego-involving climates with male students may reflect traditional gender socialization processes, where males are more frequently encouraged to compete, compare, and achieve recognition through outperforming others (Duda & Ntoumanis, 2003). Such environments tend to emphasize external rewards, peer comparison, and fear of failure—factors that can lead to anxiety, reduced intrinsic motivation, and even disengagement from learning (Ames, 1992; Papaioannou, 2007). In the context of Physical Education, this climate can create pressure to perform, especially among students with lower perceived competence, who may feel marginalized or devalued. The results suggest that although ego-involving climates may drive short-term effort in some students, they are less conducive to sustainable motivation and academic confidence—particularly when compared to task-involving climates that promote self-improvement and internal satisfaction. Therefore, while the presence of ego-involving climates in male student experiences is notable, it also raises concerns about the long-term educational cost of relying on competitive, high-pressure classroom dynamics. In this context, a controlling style further limits students’ verbal, emotional, and behavioral expression, compromising their confidence (Granero-Gallegos et al., 2022) and increasing disaffection (Patall et al., 2018). Consequently, professors with controlling tendencies may design learning environments focused on grades, comparison, and external validation of competence (Reeve et al., 2019), characteristics often found in teachers with poor instructional adaptability (Rubie‐Davies et al., 2012).

Several limitations must be acknowledged, such as the lack of control over the professors’ gender and its influence on their interpersonal style and classroom climate. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is not possible to determine the directionality of the observed associations, and any causal interpretations must be avoided. Additional limitations include non-random sampling and potential social desirability bias associated with self-report data. However, this study also presents strengths, such as its timely relevance within Mexican society and the large sample of undergraduate Physical Education students from three cities (Ensenada, Mexicali, and Tijuana).

In conclusion, the MCE scale was shown to be a valid and reliable tool for use with Mexican university students of both genders. The findings highlight that autonomy-supportive teaching is associated with higher levels of academic confidence and effort, especially among females, while male students may particularly benefit from task-involving climates. Conversely, controlling styles were associated with lower academic confidence and effort, suggesting that their use may be counterproductive. From a practical standpoint, this study underscores the importance of promoting autonomy-supportive strategies and task-oriented climates in Physical Education training programs. Therefore, it is essential to strengthen teacher education, equipping faculty with strategies to implement diverse methodologies and teaching styles shown to enhance the learning environment (Hoyo-Guillot & Ruiz-Montero, 2023; Lobo-de-Diego et al., 2024; Valldecabres & López, 2024). In addition, it is necessary to prevent the creation of gender-stereotyped environments, which could affect academic commitment and effort. Avoiding gender-based assumptions in classroom management may help improve student performance, confidence, and motivation (Stein et al., 2014). Students trained under controlling styles and ego-involving climates may later replicate such environments when teaching younger students. Future research should therefore: (a) follow these students into their professional careers and analyze how their classroom climates are perceived; (b) study the gender of current faculty and its relation to classroom climate; and (c) design experimental studies focused on implementing task-involving climates to determine their impact on students’ academic confidence and perseverance.

Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada / CBUAThis article is also related to a research stay of Dr. Raúl Fernández Baños at the Autonomous University of Baja California (November 9, 2023 – November 21, 2023), under the supervision of Prof. Roberto Espinoza Gutiérrez. In addition, this research stay was funded through the Resolution of the Vice-Rectorate for Research and Transfer, publishing the agreement of the Governing Council of January 26, 2024, which definitively approved the program “Participation in International Congresses and Scientific-Technical Meetings” within the 2023 Research Plan of the University of Granada (Official resolution in Spanish).