The aim is to analyse the efficiency of the board of directors as a corporate governance mechanism. For this purpose, we examine the effect of board composition, size, activity, leadership structure and CEO tenure on firm performance. To test our hypothesis we use a sample of 307 Spanish SMEs, none of which is listed. Our main empirical result is the negative impact of the outside directors proportion and board size on firm performance. The presence of outside directors can be said not to have resulted in improved firm performance. Despite the greater monitoring, advising and networking capacity attributed to outside directors, the firms in the sample showed a significant presence of insider directors, an aspect that may be related to their greater knowledge of the firm, with a subsequently positive effect on strategic planning decisions. The negative effect of board size could indicate that the disadvantages of worse coordination, flexibility and communication inside large boards seem to be more important than the benefits of better manager control by the board of directors.

El objetivo es analizar la eficiencia del consejo de administración como mecanismo de gobierno corporativo. Para ello, analizamos el efecto de su composición, tamaño, actividad, estructura de liderazgo y mandato del máximo ejecutivo sobre los resultados empresariales. Para contrastar las hipótesis utilizamos una muestra de 307 PYMEs españolas, ninguna de las cuales cotiza en Bolsa. Nuestro principal resultado es el efecto negativo de la proporción de consejeros externos y tamaño del consejo sobre los resultados empresariales. Se puede decir que la presencia de consejeros externos no se traduce en la mejora de los resultados de la empresa. A pesar de la mayor capacidad de control, asesoramiento y creación de redes atribuida a los externos, las empresas de la muestra presentan una significativa presencia de consejeros internos, aspecto que puede estar relacionado con su mayor conocimiento de la empresa, con el consiguiente efecto positivo en las decisiones estratégicas de la misma. El efecto negativo del tamaño del consejo puede indicar que las desventajas de la peor coordinación, flexibilidad y comunicación dentro de los consejos de gran tamaño, parecen ser más importantes que los beneficios derivados del mayor control gerencial por parte del consejo.

The efficiency of corporate board as a central institution in the internal governance of a company and its impact on firm behaviour is one of the most debated issues in literature today. Literature on boards focuses on three main questions (John & Senbet, 1998): the size of the board (Barroso Castro, Villegas Periñan, & Pérez-Calero, 2010; De Andrés, Azofra, & López, 2005; Eisenberg, Sundgren and Wells, 1998; García-Olalla & García-Ramos, 2010; Jackling & Johl, 2009; Jensen, 1993; Yermack, 1996); its composition and independence (Arosa, Iturralde, & Maseda, 2010; Barroso Castro et al., 2010; Bhagat & Black, 2000; De Andrés et al., 2005; García-Olalla & García-Ramos, 2010; Jackling & Johl, 2009; Lefort & Urzúa, 2008); and its internal structure and functioning (De Andrés et al., 2005; García-Olalla & García-Ramos, 2010; Jackling & Johl, 2009; Klein, 1998; Vafeas, 1999).

This paper adds to this empirical literature by analysing the influence of the board activity (number of meetings), leadership structure and CEO tenure as well as the size of the board and its composition on firm performance. Besides, in the context of non-listed firms, this paper studies specifically the efficiency of board of director in small and medium-sized firms.

Most research on corporate governance and boards has focused theoretically and empirically on large corporations (Daily, Dalton, & Canella, 2003; Gabrielsson & Huse, 2004). However, the literature identifies both differences and similarities in corporate governance and boards in large and small firms (Machold, Huse, Minichilli, & Nordqvist, 2011). While agency problems are also relevant to the small firm context, decision-making and control structures here are less complex and diffuse compared to large firms resulting in a comparatively diminished boards’ monitoring role (Daily & Dalton, 1993; Fama & Jensen, 1983). Owners of small firms may be more concerned about firm survival, growth rate, family welfare, succession plan, personal status, etc. than retaining short-term financial returns that are a core concern of shareholders in public companies. The different focuses of interests may affect how boards perform their tasks (Pugliese & Wenstøp, 2007). The type and content of boards’ tasks also vary between small and large firms (Zahra & Pearce, 1989). Effective governance of small firms also depends on the firm's capability of tapping board knowledge (Pugliese & Wenstøp, 2007). Finally, the impact of founders and/or key entrepreneurs on boards and governance may be greater in small firms compared to large ones (Arthurs, Busenitz, Hoskisson, & Johnson, 2009).

We conducted, following Johnson, Daily, and Ellstrand (1996), an integrated analysis of three functions of the board of directors, supervisory, advisory and networking with particular emphasis on the impact that its structure, composition and size has on firm performance. Our main empirical result is the negative impact of the outside directors proportion and board size on firm performance. The presence of outside directors can be said not to have resulted in improved firm performance. Despite the greater monitoring, advising and networking capacity attributed to outside directors, the firms in the sample showed a significant presence of insider directors, an aspect that may be related to their greater knowledge of the firm, with a subsequently positive effect on strategic planning decisions. The negative effect of board size indicate that the disadvantages of worse coordination, flexibility and communication inside large boards seem to be more important than the benefits of better manager control by the board of directors.

In that context, the rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes the theoretical basis and the hypotheses to examine. Section 3 sets out the data and procedures for analysis used in undertaking this empirical study. The main results of the investigation and their discussion are presented in Section 4. We conclude the paper in Section 5 with some conclusions and implications for management theory and practice, as well as the limitations of the investigation. The paper ends with a list of bibliographical references.

2Theoretical background and hypothesesIn recent years the attention and interest in corporate governance structures has grown significantly in management literature, especially after the financial corporate collapses happened around the world. Various published Codes of good governance have made recommendations on the size of the board, its composition, and the internal or external character of its directors. The aim is to establish effective control over the management of the firm by the board of directors and its responsibility for the firm and the shareholders.

However, governance studies have focused on large public firms instead in private small and medium sized firms (SMEs).

The interest of SMEs’ researchers has been concentrated on the need to identify the existence of governance mechanisms to guarantee the survival of SMEs.

This paper focuses on the link between firm performance and several corporate governance issues such as the composition of the board, its size, its activity, its leadership and its tenure in non-listed SMEs.

2.1Board compositionAmong the different dimensions of board of directors, board composition is one of the most debated issues for the majority of research efforts on boards. Studies on board composition classify directors as either insiders (those who are directors and managers at the same time) or outsiders (non-manager directors), since they can have quite different behaviour and incentives (De Andrés et al., 2005). Most of the corporate governance codes developed at the country level an international level (e.g., Sarbanes-Oxley Act in US, Combined Code in UK, Conthe Code in Spain, OECD Code) require boards of directors to have a combination of inside and outside directors.

In the context of corporate governance, agency theory implies that adequate monitoring mechanisms need to be established to protect shareholders from management's self-interests and outside directors are supposed to be guardians of the shareholders’ interests via monitoring. Therefore a high proportion of outside directors on the board could have a positive impact on performance by monitoring services (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). Support for the agency theory, scholars has suggested alternative explanations for the determinants of board composition. So, Hermalin and Weisbach (1998), Raheja (2005), Harris and Raviv (2008), and Adams and Ferreira (2007), model the theoretical determinants of board composition, specifically the roles of insiders and outsiders (Linck, Netter, & Yang, 2008). For example, Raheja (2005) argues that insiders are an important source of firm-specific information for the board and their experience can improve firm performance, but they can have distorted objectives due to private benefits and lack of independence from the CEO. Compared to insiders, outsiders provide superior firm performance as a result of their more independent monitoring, but are less informed about the firm's constraints and opportunities. A growing body of research suggests that a strong and vigilant board of directors can have a significant positive influence on the value-creating potential of SMEs by favouring change and innovation in strategic decision-making (Gabrielsson, 2007a). In small firms there may be problems with inconsistent information between managers and shareholders due to vague divisions of responsibilities and the absence of formal reporting systems. Also, the markets for corporate and managerial control may function less well in these kind of firms (Gabrielsson & Winlund, 2000). Medium-size companies can be expected to benefit from the external supervision that a governing board can offer, for example by providing attention to critical issues facing the company and directing the company towards appropriate competitive strategies by allocating resources to innovative projects and procedures necessary for responding to changes in the marketplace (Gabrielsson, 2007a). Hermalin and Weisbach (1991) support the argument that outside directors are more effective monitors and a critical disciplining device for managers but they posit no significant relationship between performance and outsiders’ proportion on the board of directors. From an agency theory perspective, the board can be used as a monitoring device for shareholder interests to safeguard their investments (Fama & Jensen, 1983) and the board of directors can function as an exceptionally relevant information system for stakeholders to monitor executive behaviour and firm performance (Gabrielsson & Winlund, 2000).

Besides agency theory, several other theoretical perspectives have been used in order to explain board roles and the composition of the board of directors. The service role can be related to the resource based view and resource dependence theory, where boards are considered to control interorganizational dependencies and act as a strategic resource for securing critical resources for the firm (Pfeffer, 1973; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). According to resource based theory, a firm's internal environment, its resources and capabilities, is critical for creating sustainable competitive advantage (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). Knowledge is an intangible resource that can sustain a competitive advantage in the long term and one way to enhance its acquisition is involvement in firm ownership. Small firms are however generally characterized by a lack of internal resources, and in-house knowledge may in many cases be scarce or non-existing (Storey, 1994). It becomes very important the advisory role of the board (Daily & Dalton, 1993), as they can provide comprehensive and complementary outside knowledge that can be used by the management team in formulating and implementing their strategies (García-Olalla & García-Ramos, 2010; Machold et al., 2011). The appearance of outside directors on the board of small private firms will reflect the service and resource needs of the CEO rather than the control role (Fiegener, Brown, Dreux, & Dennis, 2000). Thus, the knowledge and skills of outside directors may complement, or compensate for, those of managers and internal directors (Huse, 1990). The service role is therefore linked to the board's giving of advice and to the board's work in legitimizing the firm and providing it with important strategic networks (Gabrielsson & Winlund, 2000).

According resource dependence theory, outsiders seen as a linking mechanism between the firm and its environment that may support the managers in the achievement of the various goals of the organization (Johnson, Daily, & Ellstrand, 1996; Zahra & Pearce, 1989). These directors are known and powerful persons that take profit of their personal networks in order to increase the legitimacy, the reputation and the stock of resources controlled by the company (Pfeffer, 1973; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). A critical factor of growth within SME is the access to external financing sources, and these firms tend to have fewer alternatives for managing their resource dependencies (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). Therefore, the board's resource dependence role may take on added importance in these firms (Daily & Dalton, 1993; Pfeffer, 1973). Also, outside directors can be an effective means for overcoming the human resource limitations that often plague small firms (Daily & Dalton, 1993; Huse, 1990).

Outside directors increases supervision, introduces independent considerations in decision-making, and increases knowledge about the business. Accordingly the following hypothesis is presented.H1 The proportion of outside directors of SMEs is positively associated with firm performance.

One of the most analysed variables in the study of corporate governance is the size of the board. It is not clear the effect of the size of the board on firm performance (Barroso Castro et al., 2010; Bennedsen, Kongste, & Nielsen, 2008).

A board of directors with high levels of links to the external environment would improve a company's access to various resources thus improving corporate governance and firm performance. Surveys of board practices have reported that small companies have relatively few directors on their board, ranging between three and seven members and that in addition to the founder or owner–manager, there may be one or two family members on the board (Gabrielsson, 2007b). There has been some empirical evidence to suggest that increased board size can have a positive association with performance (Forbes & Milliken, 1999; Goodstein, Gautam, & Boeker, 1994; Van den Berghe & Levrau, 2004). Proponents of this view argue that a larger board will bring together a greater depth of intellectual knowledge and therefore improve the quality of strategic decisions that ultimately impact on performance. Besides, incorporating the advisory role in the analysis, an additional director brings more human capital to the company, increasing board information and specific knowledge about the business. This contributes to the efficiency of the advisory role and therefore, to better firm performance (Adams & Ferreira, 2007; De Andrés & Rodríguez, 2008; Linck et al., 2008).

However, while the abilities of the board can increase as more directors are added, the benefits can be outweighed by the costs in terms of the poorer communication and decision-making associated with larger groups (Cheng, 2008). According to Jensen (1993), large corporate boards may be less efficient due to difficulties in solving the agency problem among the members of the board. As groups increase in size they become less effective because the coordination and process problems overwhelm the advantages from having more people to draw on. Yermack (1996) presents evidence that small boards of directors are more effective and that firms achieve higher market value. For instance, some authors show an inverse relationship between firm value and the size of the board (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Yermack, 1996).

Thus, the effect of board size on firm performance is a trade-off between benefits and drawbacks (García-Olalla & García-Ramos, 2010). In this sense, we expect a non-linear relationship between the size of the board and firm performance. Our second hypothesis states the following hypothesis.H2 There will be an inverted-U-shaped relationship between the size of the board and firm performance for SMEs.

One aspect in relation with the board internal structure is board activity. Following Jackling and Johl (2009), one way to measure the board activity, is the frequency of board meetings. The meetings frequency can be a factor that helps us to assess whether the board of directors is an active or a passive board. Board meetings must be held frequently enough to let the board get continuous reports concerning the firm's situation (Gabrielsson & Winlund, 2000). The frequency of the board's meetings can offer information on the importance attributed to it, since the greater number of meetings, the more information is offered to the others and there are more issues to decide on the board. The meetings are the most usual occasion to discuss and exchange ideas in order to monitor managers (Conger, Finegold, & Lawler, 1998). From this point of view, the more frequent the meetings, the more detailed the control of the managers, and the greater the shareholder wealth. Lipton and Lorsch (1992) suggest that the greater frequency of meetings is positively associated with performance. The board cannot be expected to monitor firm performance if they are not given the opportunity to do this (Gabrielsson & Winlund, 2000).

An opposing view professed by Jensen (1993) is that routine tasks absorb much of a board's meeting time and thus limit the opportunities for outside directors to exercise meaningful control over management (Jackling & Johl, 2009). Given that the CEO is charged with fixing the agenda of the meeting, that the time of the outsider directors is scarce and that routine tasks take up a large proportion of the time, more meetings do not necessarily imply better monitoring (De Andrés et al., 2005). Lipton and Lorsch (1992) suggest that the most widely shared problem directors face is lack of time to carry out their duties. However, some evidence suggests that the association between number of meetings and performance is more complex than previously reported (Vafeas, 1999). It would be interesting to include questions related to the “quality of meetings” such as to what extent are meetings used for routine tasks as opposed to time devoted to substantive issues.

Previous studies in firms with a concentrated ownership structure confirm the existence of proactive boards in companies, so that increased activity in its roles of supervision and advice is supported by favourable results of the firm performance (De Andrés & Rodríguez, 2008; García-Olalla & García-Ramos, 2010).

According to these arguments and following also Jackling and Johl (2009), we propose the third hypothesis.H3 There is a positive association between board activity (in terms of meeting frequency) and firm performance for SMEs.

Another aspect to deal with when analyzing the board structure is the coincidence in the same person of the figures of the chairman and chief executive. Prior literature acknowledges that the type of board leadership and role of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) can have an influence on firm performance. A substantial body of research has focused on the association between firm performance and CEO leadership (Daily, McDougall, Covin, & Dalton, 2002; Dalton, Daily, Ellstrand, & Johnson, 1998). The empirical evidence is no conclusive on CEO duality, and several studies even find no significant effect on firm performance (Braun & Sharma, 2007).

García-Olalla and García-Ramos (2010,p. 8) argue that “from the perspective of the advisory function, the presence of the CEO on the board may have a positive effect on firm performance, as he/she has specific knowledge about the company, its strategic direction, its investment opportunities etc., so he/she can help to optimize decision-making”. Besides, advocates of stewardship theory argue that authoritative decision-making under the leadership of a single individual (as both chairman and CEO) leads to higher firm performance (Donaldson & Davis, 1991). CEO duality eliminates confusion and conflict between the CEO and chairman and thus allows for smoother, more effective and consistent strategic decision-making and implementation (Baliga, Moyer, & Rao, 1996; Brickley, Coles, & Jarrell, 1997; Chahine & Tohmé, 2009; Harris & Helfat, 1998). Boyd (1995) discusses the notion of stewardship behaviour, in which the CEO is concerned with doing the job right and effectively guiding the firm. He argues that dual structure leadership might consequently have a positive effect on firm value in environments or conditions characterized by scarce resources and high complexity, such as in the context of emerging markets (Chahine & Tohmé, 2009).

Small firms differ from the large ones in several important ways, including more concentrated ownership structures and role integration, making CEO duality a much more common phenomenon in the small business setting (Machold et al., 2011). In small firms, the CEO and board chairperson position is usually held by one person. This practice has drawn many criticisms according to agency theory (Pugliese and Wenstøp, 2007).

However, agency theoretic arguments imply a separation of the two positions (Coles & Hesterly, 2000; Fama & Jensen, 1983; Finkelstein & D’Aveni, 1994; Jensen & Meckling, 1976). The argument behind the need for a separation of the CEO and board chairperson roles is that the board of directors is expected to monitor the actions of top management and evaluate their performance (Gabrielsson, Huse, & Minichilli, 2007). Such a powerful CEO may be driven by self-interest, and unless restricted from doing otherwise, will undertake self-serving activities that could be detrimental to the economic welfare of the principals (Deegan, 2006; Rashid & Lodh, 2011). A centralized leadership authority may thus lead to management's domination of the board, which results in poor performance (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). In SMEs the independent leadership structure may lead to a power balance between the CEO and chair of the board may enhance the firm performance (Rashid & Lodh, 2011).

According to these arguments the relationship between CEO duality and firm performance is expected to be negative (Chahine & Tohmé, 2009; Chen & Jaggi, 2000).

Besides, the existing Codes of good governance clearly do not favour a particular position and, although they suggest the differentiation of the two positions, they led the decision on the firm. According to these arguments and following also Jackling and Johl (2009), we propose the next hypothesis.H4 There is a positive association between the separation of the figures of CEO and chairman and firm performance for SMEs.

The Resource Based View (Barney, 1991; Hillman, Cannella, & Paetzold, 2000) suggests board members are resources for the firm, and will be regarded as being of greater or lesser value in view of their own competence, knowledge, or experience (Barney, 1991). A long tenure on a board brings with it positive aspects. Longer CEO tenure could suggest a long-term commitment to the firm. Longer tenures facilitate lengthy investment time horizons and provide investment incentives and stewardship (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2006). Knowing the average tenure of the CEO may be helpful to know the possibility of the existence of a situation of convergence of interests or entrenchment by the CEO.

However, along with these positive connotations, more significantly, negative aspects can appear (Barroso Castro et al., 2010). In this respect some studies suggest that long tenures are associated with a higher resistance to change (Musteen, Barker, & Baeten, 2006). Golden and Zajac (2001) suggest that extended tenure of board members is associated with a greater rigidity, and can result in trenching behind existing practices and procedures, with directors distancing themselves from new ideas. Moreover, according to Vafeas (2003), board members who serve longer on the board and who therefore have greater experience are more likely to form friendships and less likely to supervise the management. The information about the CEO tenure would serve to know if the rotation is relatively common, which gives a notion of efficiency in the functioning of the board of directors. Having established a relatively short tenures, should help to increase the capacity for monitoring of this body, because of the rotation promotes the appearance of new people and, therefore, different attitudes and views on certain situations or decisions.

In this context, the following hypothesis is proposed.H5 There is a negative association between the length of the tenure of the CEO and firm performance for non-listed SMEs.

We conducted this study on Spanish firms included in the SABI (Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System) database for 2006. We imposed certain restrictions on this group of companies in order to reach a representative set of the population. First, we eliminated companies affected by special situations such as insolvency, winding-up, liquidation or zero activity. Second, restrictions concerning the legal form of companies were imposed: we focused on limited companies and private limited companies as they have a legal obligation to establish boards of directors. Third, we eliminated listed companies. Fourth, we studied only Spanish firms that had between 50 and 250 employees, i.e., companies large enough to ensure the existence of a suitable management team and a controlling board to monitor their performance. Finally, companies were required to have provided financial information in 2006. With this condition, the sample under study comprised 2958 non-listed Spanish SMEs that had, according to SABI database, between 50 and 250 employees. We based our definition of SME on the official EU definition (European Union, 2003) whilst using a lower limit of 50 employees to exclude firms without a well-established board of directors.

3.2DataData were collected by means of telephone interviews, a method that ensures a high response rate, and financial reporting information was obtained from the SABI database. To guarantee the highest possible number of replies, managers were made aware of the study in advance by means of a letter indicating the purpose and importance of the research. In cases where they were reluctant to reply or made excuses, a date and time were arranged in advance for the telephone interview. The final response rate was approximately 10.4%, and the interviewees were persons responsible for management at the firms (financial managers in 56.48% of the cases, the CEO in 31.06%, the president in 1.54% of the cases, and others in 10.92%).

The questionnaire collects information on the variables required for the study that could not be obtained from the SABI database and which it was considered would be more reliably collected through a survey; in particular, information regarding the ownership structure and composition of the board and company management.

3.3Definition of variablesFirm profitability: The firm's profitability, measured in terms of return on assets (ROA), was taken as a dependant variable. The ROA measures the capacity of a firm's assets to generate profits and it is considered to be a key factor in determining the form's future investment. It is therefore used as an indicator of firm profitability.

The ROA has been defined as EBIT (earnings before interests and taxes) between total assets, not taking into account the firm's financial performance (Anderson & Reeb, 2003). EBIT is a traditional measurement which does not include capital costs, i.e., it only includes the operating margin and operating income.

Board composition: Theoretically, from an agency perspective, it is claimed that a greater proportion of outside directors on boards act to monitor independently in situations where a conflict of interest arises between the shareholders and managers. Agency theory is based on the premise that there is an inherent conflict between the interests of a firm's owners and its management (Fama & Jensen, 1983).

A high proportion of outside directors on the board is therefore viewed as potentially having a positive impact on performance (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). A greater proportion of outside directors will monitor any self-interested actions by managers, and will therefore be associated with high corporate performance (Nicholson & Kiel, 2007).

This variable has been generated representing the composition of the board (OUTSIDERS), calculated as the percentage of external directors on the board (Anderson & Reeb, 2003; Barontini & Caprio, 2006). The function of this variable is to measure the board's monitoring capacity, in order to analyse its influence on the firm's profitability.

Board size (BOARDSIZE) is measured using the natural logarithm of total number of members of the board of directors (Anderson & Reeb, 2003; De Andrés et al., 2005; Jackling & Johl, 2009).

Board activity (MEET) is measured in terms of number of board meetings held in a reporting year. This is an interesting variable since it can be used as a proxy for the intensity of board activity.

Leadership (DUALITY) is measured as a dummy variable which takes value 1 if the chairman and the CEO are the same person and 0 otherwise.

CEO tenure (TENURE) is measured in terms of the average number of years of the tenure. Tenure can take four values: value 1 if the tenure is less than 4.5 years; value 2 if the tenure is between 4.5 and 10 years; and value 3 if the tenure is longer than 10 years.

Control variables: Firm size (SIZE) was measured using the natural logarithm of total assets (Anderson & Reeb, 2003; Barontini & Caprio, 2006; Wang, 2006).

The number of directors is a relevant feature that can have much to do with the board's monitoring and control activity. Whereas the ability of the board to monitor can increase as more directors are added, the benefits can be outweighed by the costs in terms of the poorer communication and decision-making associated with larger groups (Jensen, 1993; Lipton & Lorsch, 1992).

On the above basis and given the potential importance of board size, we also created a variable measured using the natural logarithm of the number of directors in the firms in the sample.

Growth opportunities (GROWTHOP), following Scherr and Hulburt (2001) were calculated as Sales0/Sales−1. In this case, firms that grew most in the past were considered to have most chance of growth in the future.

Borrowing level (LEV) was measured as the quotient between total debt and total assets (Coles, Daniel, & Naveen, 2005; Wang, 2006).

Firm age (AGE) was measured as the natural logarithm of the number of years since the firm was incorporated.

The sector (SECT) was measured by means of dummy variables, using the standard industrial classification.

3.4MethodWe apply a cross-sectional ordinary least-square (OLS) regression model to test the hypotheses presented in the preceding section. Drawing on previous research on corporate governance, we also include five control variables to minimize specification bias in the hypothesis testing.

After testing the first version of the model, which includes just the outsiders variable, we do seven more regressions to take into account the composition of the board and its functioning. Control variables were added to the right hand side of the equation including. In the first six regressions we analyse the effect of each variables, board composition, board size, board leadership, board activity and CEO tenure on firm performance. The last two regressions reflect the impact of all variables on firm performance.

The study expects a positive association between board composition (outsiders) and performance, anticipating that firms with a greater proportion of outside directors have better performance. Also, the coefficient of leadership is expected to be negative, signifying that higher agency costs in the case of dual leadership and CEO. We expect a non-linear relation of board size, which indicates that there is an optimum level of board members. Beyond a number of members, the inefficiencies outweigh the advantages. For board activity, a positive relationship is expected for number of meetings (meet) and firm performance based on resource dependency theory. A negative relationship is also expected for the director's tenure and firm performance.

To test for multicollinearity, the VIF was calculated for each independent variable. Myers (1990) suggests that a VIF value of 10 and above is cause for concern. The results (not shown in this paper) indicate that all the independent variables had VIF values of less than 10.

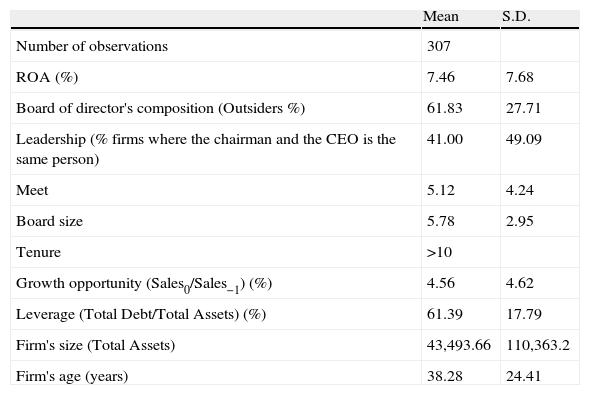

4Results and discussionTable 1 presents descriptive statistics for the variables in the analysis. We show mean and standard deviation values for the firms in the sample. The results show that, on average there are 61.83% of outside directors on the board. In relation to the leadership structure, in the 41% of the firms in the sample, both the figures of Chairman and CEO are the same person. In terms of board activity, the sample firms held a mean of 5.12 meetings in a year. Given that the Good Governance Codes in Spain require a minimum of four board meetings a year, the firms in the sample comply with the rule.

Descriptive statistics of sample firms: mean and standard deviation values for variable measures.

| Mean | S.D. | |

| Number of observations | 307 | |

| ROA (%) | 7.46 | 7.68 |

| Board of director's composition (Outsiders %) | 61.83 | 27.71 |

| Leadership (% firms where the chairman and the CEO is the same person) | 41.00 | 49.09 |

| Meet | 5.12 | 4.24 |

| Board size | 5.78 | 2.95 |

| Tenure | >10 | |

| Growth opportunity (Sales0/Sales−1) (%) | 4.56 | 4.62 |

| Leverage (Total Debt/Total Assets) (%) | 61.39 | 17.79 |

| Firm's size (Total Assets) | 43,493.66 | 110,363.2 |

| Firm's age (years) | 38.28 | 24.41 |

According to board size, the mean value is 5 members per board, which is in line with corporate governance recommendations. It seems that the boards of the firms in the sample are quite small. Finally, if we analyse the tenure of the CEO and directors, it is on average longer than 10 years (Table 2).

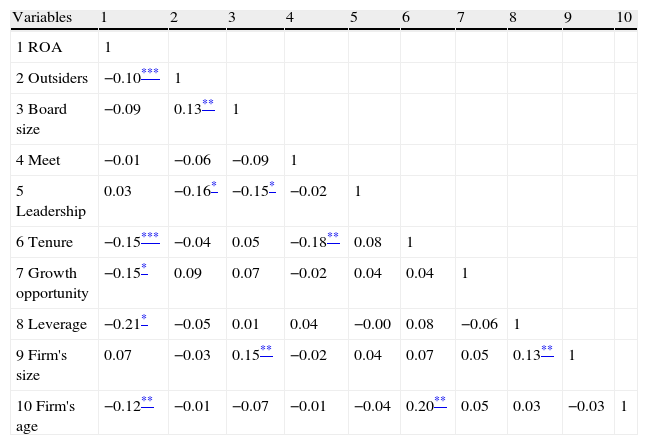

Correlation data.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1ROA | 1 | |||||||||

| 2Outsiders | −0.10*** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3Board size | −0.09 | 0.13** | 1 | |||||||

| 4Meet | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.09 | 1 | ||||||

| 5Leadership | 0.03 | −0.16* | −0.15* | −0.02 | 1 | |||||

| 6Tenure | −0.15*** | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.18** | 0.08 | 1 | ||||

| 7Growth opportunity | −0.15* | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1 | |||

| 8Leverage | −0.21* | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.00 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 1 | ||

| 9Firm's size | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.15** | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.13** | 1 | |

| 10Firm's age | −0.12** | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.20** | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 1 |

In relation to control variables, Table 1 shows the firms in the sample have on average an age of 38 years, 43,493.66€ of total assets, their level of indebtedness is around 61% and their growth opportunity is 4.56%.

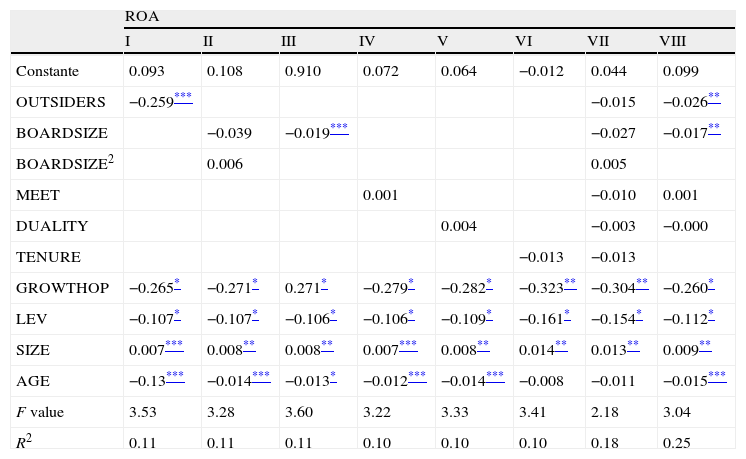

Table 3 sets out the results of our regression evaluating the influence of board composition on business performance for family and non-family firms.

Relationship between the board composition and firms performance in family and non-family firms.

| ROA | ||||||||

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | |

| Constante | 0.093 | 0.108 | 0.910 | 0.072 | 0.064 | −0.012 | 0.044 | 0.099 |

| OUTSIDERS | −0.259*** | −0.015 | −0.026** | |||||

| BOARDSIZE | −0.039 | −0.019*** | −0.027 | −0.017** | ||||

| BOARDSIZE2 | 0.006 | 0.005 | ||||||

| MEET | 0.001 | −0.010 | 0.001 | |||||

| DUALITY | 0.004 | −0.003 | −0.000 | |||||

| TENURE | −0.013 | −0.013 | ||||||

| GROWTHOP | −0.265* | −0.271* | 0.271* | −0.279* | −0.282* | −0.323** | −0.304** | −0.260* |

| LEV | −0.107* | −0.107* | −0.106* | −0.106* | −0.109* | −0.161* | −0.154* | −0.112* |

| SIZE | 0.007*** | 0.008** | 0.008** | 0.007*** | 0.008** | 0.014** | 0.013** | 0.009** |

| AGE | −0.13*** | −0.014*** | −0.013* | −0.012*** | −0.014*** | −0.008 | −0.011 | −0.015*** |

| F value | 3.53 | 3.28 | 3.60 | 3.22 | 3.33 | 3.41 | 2.18 | 3.04 |

| R2 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.25 |

In our first regression we examined the influence of outside directors on firm performance. As noted in Table 3 (column I), the overall model is significant (F statistic=3.53; p<0.01 and R2 is 0.11). The results were not expected. Our results show a significant negative relationship (β1=−0.259) between outsiders and firm performance. Hypothesis 1 was not supported. This negative relationship between the percentage of outsiders on the board and firm performance are consistent with studies indicating that firms with a majority of board outside directors have poorer performance (Agrawal & Knoeber, 1996; Yermack, 1996). These results appear to contradict the assumption that outside directors have an important monitoring, advising and networking function and in contrast justify the presence of insider directors in firms in the sample.

The reasons put forward to explain the negative relationship between the presence of outside directors and performance vary. Hermalin and Weisbach (1991) suggest that both inside and outside directors may fail to perform their job of representing shareholders’ interests properly, i.e., it cannot be concluded that outsiders perform their activity better than insiders. Likewise, inside directors offer advice and conveying knowledge to the CEO on the firm's day-to-day operations. The presence of insiders on the board makes it easier for the other directors to view them as potential top executives, since they can assess their skills more simply from seeing them act on the board itself (Bhagat & Black, 2000). It also needs to be said that each type of director has a specific role on the board (Baysinger & Butler, 1985). Inside directors have a greater knowledge of the firm than outsiders (Raheja, 2005), who are often unfamiliar with the working of the firm. Outsiders’ independence makes them quicker to react in a crisis situation, but they have a greater chance of making mistakes as a result of that lack of knowledge.

We analyse the effect of board size on firm performance in column II and III (F statistic=3.28; p<0.01 and R2 is 0.11; F statistic=3.60; p<0.01 and R2 is 0.11). We expect a non-linear relationship between the two variables. Our results (column II) do not show an optimal level of board size because the coefficients of board size and its square are not significant (β1=−0.039 and β2=0.006). However, our findings (column III) show a significant negative relationship between board size and firm performance (β1=−0.019).

The results support prior studies (De Andrés et al., 2005; Eisenberg et al., 1998; Yermack, 1996), and confirm that small boards of directors are more effective. Nevertheless, the results contrast with the earlier work of García-Olalla and García-Ramos (2010), Nicholson and Kiel (2007) and Van den Berghe and Levrau (2004) who find that increasing the number of directors improves firm performance. Our findings show, as indicated by Jensen (1993), that the benefits of an increase in size seem to be outweighed by the problems of poorer coordination, communication and flexibility that are associated with large boards.

The fourth regression (column IV, F statistic=3.22; p<0.01 and R2 is 0.10) analyse the relation between the board's activity, measured by the number of meetings per year, and firm performance. We hypothesised a positive relationship between the two variables, but the results do not show any significant relationship between the frequency of boards meetings and firm performance. Although the sign of the coefficient is positive as we expected (β1=0.001), its lack of significance does not allow us to accept the hypothesis 3. Another explanation for the insignificance of this finding could be the more complex relationship between this two variables or the possibility of a lag effect in that boards respond to poor performance by increasing board activity which in turn affects following years’ performance (Vafeas, 1999).

In relation with board activity, we can analyse other aspects, such as how far in advance the directors receive the agenda and the information needed to properly prepare the meetings. Therefore, the analysis of this aspect will give an idea of whether the directors have sufficient time to analyse the material received and prepare the meetings. Otherwise, these meetings can turn into purely informative, as the chairman set out the points of the day and directors can hardly take part or exposed his points of view if they have not had time to consider the information received. Most firms in the sample give the information needed to prepare the meeting with just less time than a week. With this information it seems that the sample's firm could have passive boards.

Regarding leadership structure, we analyse (column V) the relationship between the board leadership and firm performance. Our findings (F statistic=3.33; p<0.01 and R2 is 0.10) do not show that boards whose chairman is not a CEO performs significantly better than those whose chairman is also a CEO. The insignificance of the duality variable (β1=0.004) although no consistent with Coles, McWilliams, and Sen (2001) and Peel and O’Donnell (1995) it is consistent with prior findings of Daily and Dalton (1994), Vafeas and Theodorou (1998), Elsayed (2007) and Jackling and Johl (2009). These results do not support the hypothesis 4 which postulate that the separation of the figures of CEO and chairman is positively associated with firm performance.

In the column VI we analyse the relation between the CEO and directors tenure and firm performance. In this case neither do we find any relationship between these two variables because the coefficient is not significant (β1=−0.013). Although the coefficient is negative as we expected, it is no significant, so we cannot accept hypothesis 5. The tenure on average is longer than 10 years, but it seems that this aspect does not have any influence on firm performance.

Finally we analyse the combined effect of all variables. Comparing models VII and VIII we can observe that the model is more robust when we do not include the non-linear effect of board size and CEO tenure variables. This fact may suggest that these variables are not relevant for firm performance.

5ConclusionThis paper analyse the efficiency of the board of directors as a corporate governance mechanism. For this purpose, we examine the effect of board composition, size, activity, leadership structure and CEO tenure on firm performance. We apply a cross-sectional ordinary least-square (OLS) regression model to test the hypotheses presented. After testing the first version of the model, which includes just one variable (OUTSIDERS), we do seven more regressions to take into account the composition of the board and its functioning. To test our hypothesis, contrary to most previous studies, we did not focus on large listed companies but adopted a sample of 307 Spanish SMEs, none of which is listed.

Our main empirical result is the negative impact of the outside directors proportion and board size on firm performance. The presence of outside directors can be said not to have resulted in improved firm performance. Despite the greater monitoring, advising and networking capacity attributed to outside directors, the firms in the sample showed a significant presence of insider directors, an aspect that may be related to their greater knowledge of the firm, with a subsequently positive effect on strategic planning decisions, which means a greater trust with inside directors in SMEs. The negative effect of board size indicate that the disadvantages of worse coordination, flexibility and communication inside large boards seem to be more important than the benefits of better manager control by the board of directors.

In sum, our findings, as well as the ones of García-Olalla and García-Ramos (2010), contradict the widespread belief that smaller, independent and proactive boards, as well as an effective separation of the figures of the chairperson of the board and the CEO, are always more effective.

Our research has some implications for SMEs and their advisors. Our results show which is the most suitable structure for board of directors in order to improve its performance. Besides, the findings show that outsiders do not add value to the firm, so we think that the problem can be the criteria for choosing directors. Outsider selection is important because must give professionalism to the board. Therefore, outside directors are to be selected carefully in order to be adequately qualified to carry out the responsibilities. Outsiders must have skills, experience in other firms, knowledge of corporate management and economic independence on the compensation they receive. It is also interesting that the consultants recommend firms to have a well-balanced equilibrium between outside and inside directors because of the important and concrete role they play on it, exercising a more effective function on the board, leading to better performance.

This research has to deal with some limitations. First, our data are cross-sectional in nature and therefore, we cannot clearly infer on causality. Only a panel data sample will allow testing and complementing our findings. Second, data were collected exclusively in Spain, therefore limiting the possibility of generalizing our findings.

The authors thank Cátedra de Empresa Familiar de la UPV/EHU for financial support (DFB/BFA and European Social Fund). This research has received financial support from the UPV/EHU (Project UPV/EHU 10/30).