This paper addresses the study of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction of a company with its main supplier from different variables highlighted in the literature. Specifically, the objective is to analyse the effect of trust, commitment and switching costs on satisfaction, as well as the effect of this satisfaction on co-creation of value, continuity of the relationship and Information and Communication Technology coordination. To achieve this goal, a structural equation model was estimated with a sample of 256 tourist agencies. The results confirm the proposed relationships to explain the satisfaction process. The trust of the tourism company with its main supplier is the main antecedent of satisfaction with the relationship. The satisfaction of the tourism company with its supplier contributes to the co-creation of value and improves Information and Communication Technology coordination. Interesting theoretical implications and for management of relationships between companies are shown.

The long-term orientation of companies based on the continuity of relationships with their buyers is the fundamental basis of relationship marketing (Andriotis & Paraskevaidis, 2021). In the B2B environment, the proper management of these relationships is especially complex due to the variety of participating companies (manufacturers, public agents, etc.), the simultaneity of roles that they can exercise in exchange relationships (supplier, competitor, etc.) and the large amount of resources that companies invest in building collaborative relationships with their partners aimed at creating and maintaining competitive advantages (Berenguer-Contrí, Gallarza, Ruiz-Molina, & Gil-Saura, 2020).

The academic and practical interest that this type of relationship has attracted in recent years is remarkable. Based on the social exchange theory, companies seek to maintain relationships with suppliers that really add value and contribute to profits. In this line, several authors address the study of variables and models that attempt to explain the nature of relationships between companies (e.g. Andriotis & Paraskevaidis, 2021; Jeong & Oh, 2017; Moliner-Velázquez, Fuentes-Blasco, & Gil-Saura, 2014). Some studies have investigated the process of building relationships based on variables such as trust, commitment and satisfaction (e.g. Berenguer-Contrí et al., 2020; Jeong & Oh, 2017; Roberts-Lombard, Mpinganjira, & Svensson, 2017; Schmitz, Schweiger & Daft, 2016). However, there are certain disagreements regarding the variables that are antecedent or consequential. Some authors point out that in some way satisfaction predicts trust and commitment (e.g. Theron, Terblanche, & Boshoff, 2011), while for others these variables are antecedents (e.g. Berenguer-Contrí et al., 2020). The literature also reveals that switching costs play an important role in commitment (Ojeme, Robson, & Coates, 2018) and, therefore, can influence the satisfaction process. On this matter, there is also no agreement on the type of effect or type of antecedent, whether mediator or moderator, that this variable has in relationships (Matzler, Strobl, Thurner, & Füller, 2015).

The studies that have addressed the responses of satisfaction with the relationship highlight those of a behavioural nature related to continuity, coordination or joint collaboration. Among them, value co-creation (Berenguer-Contrí et al., 2020; Zhang, Jiang, Shabbir, & Du, 2015), relationship continuity (Roberts-Lombard et al., 2017) and ICT coordination (Daulatkar & Sangle, 2016) are of particular note as they are especially relevant in B2B literature but with little scope for application in the tourism context.

Despite this interest, research on the variables that intervene in the process of building relationships, on the type of influence that these variables exert, and on the conditions that are necessary for relationships to be beneficial is still limited (Andriotis & Paraskevaidis, 2021; Roberts-Lombard et al., 2017). This gap is seen above all in the tourism industry, one of the largest and fastest growing sectors in the world and the most affected of all by the worldwide outbreak of COVID-19 (UNWTO, 2022). Thus, the effects that the global pandemic derived from COVID-19 is having on the business profitability must also be considered since this crisis has caused important changes in the survival of service companies. All these changes are revealing the fragility of some sectors in their process of adapting to this new business reality (Mele, Russo-Spena, & Kaartemo, 2021), especially those linked to in the tourism sector. In this highly competitive, turbulent and uncertain industry, closely linked to the development of technologies, tourism companies establish a wide variety of relationships with multiple participants in the marketing channel, so proper management of these relationships is key to the future of the company (Davcik & Sharma, 2016).

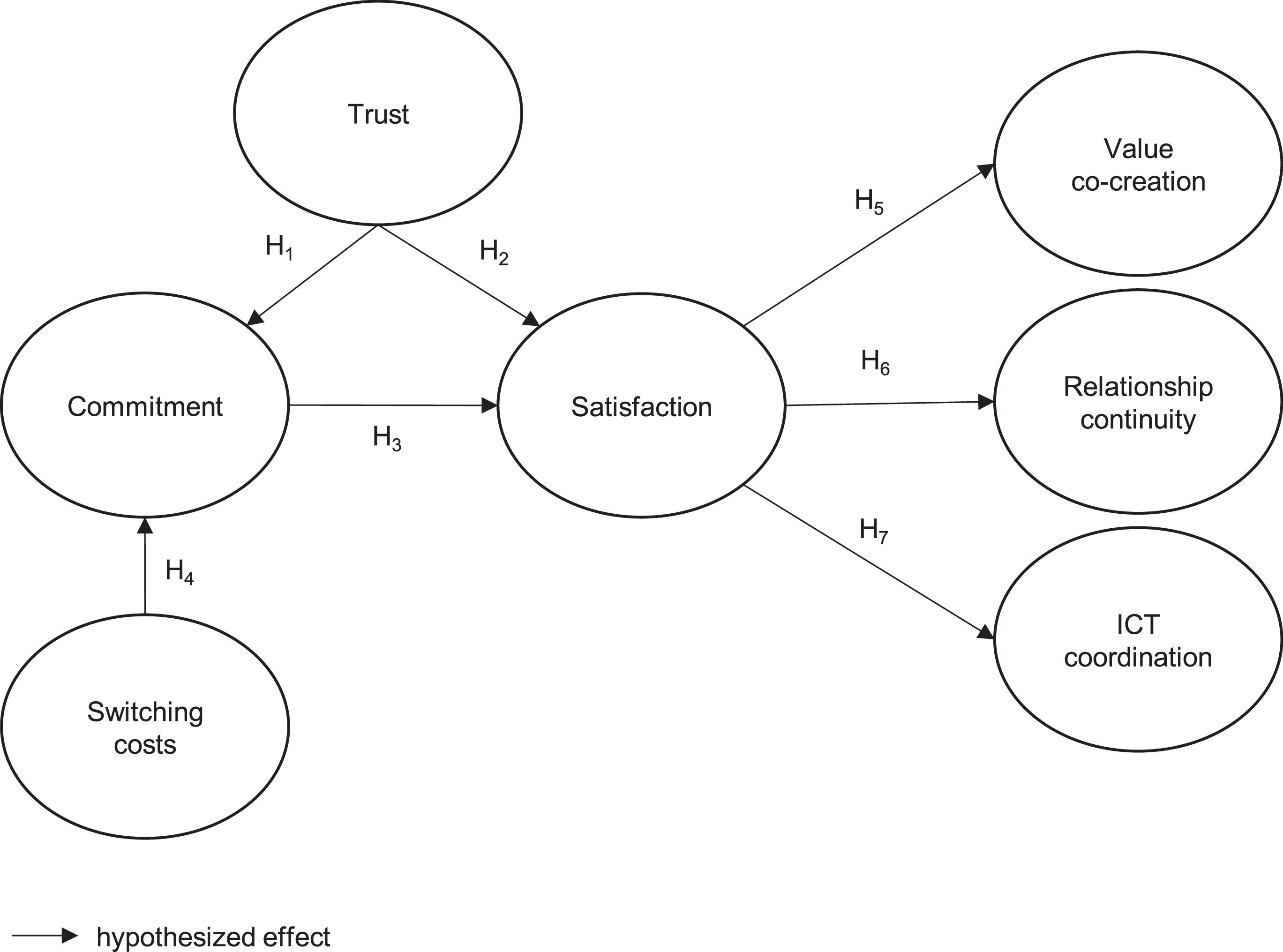

To contribute to this line of research focused on relationships between tourism companies, the aim of this work is to analyse the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction, with a dual objective:

Regarding the antecedents, study the effect that trust, commitment and switching costs have on satisfaction.

Regarding the consequences, analyse the effect that satisfaction has on value co-creation, relationship continuity and ICT coordination.

Therefore, it is proposed that satisfaction is the result of switching costs, trust and commitment and, in turn, is an antecedent of continuity, value co-creation and ICT coordination. The novel concept of this work lies in validating a theoretical model that collects this type of constructs associated with relationships between tourism companies. Although there are numerous works applicable to services in the B2B environment (e.g. Ojeme et al., 2018; Roberts-Lombard et al., 2017), there are few contributions on the satisfaction process in relationships between tourism companies. Therefore, this work contributes to the relationship marketing literature in the B2B context in tourism, providing empirical evidence on the causes and consequences of satisfaction.

2Literature review and model proposalThe theory of social exchange establishes that the construction of relationships, in both B2C and B2B contexts, must be based on two basic pillars: the voluntary exchange of value that benefits the parties involved and the evaluation that they make of the costs and benefits derived from the relationship (Liu, Min, Zhai, & Smyth, 2016). In the B2B context, these premises imply that a company will assess the future of the relationship with its partner by analysing aspects such as economic benefits, trust, commitment, past satisfaction and its involvement in the relationship continuity. Therefore, these variables are going to be key factors when building relationships between companies.

Satisfaction is the main component in relationship management since it influences the desire to maintain it in the long term (Geyskens & Steenkamp, 2000), as well as subsequent responses such as buy-back or loyalty (Eggert & Ulaga, 2002). In general, satisfaction in B2B has been defined as an affective influence on the valuation that a company makes of the relationship with its supplier (De Wulf, Odekerken-Schröder, & Iacobucci, 2001). It has a general and accumulated nature as it includes the evaluation of all the stages of the relationship between the parties (Kundu & Datta, 2015).

The most recent contributions on satisfaction in B2B focus on the study of relationships, separating the advantages of the social sphere of exchange from the strictly economic (Jiang, Shiu, Henneberg, & Naude, 2016). In this way, it is possible to differentiate between economic and social satisfaction. Economic satisfaction is a channel member's positive affective response to the economic rewards such as sales, margins or discounts linked to efficiency and effectiveness, while social satisfaction is the evaluation that a channel member makes of the psychosocial aspects of their relationship such as gratitude, ease or values (Geyskens & Steenkamp, 2000).

Taking satisfaction as the central axis of relationships between companies, we review below the constructs that can make up the proposed process on its antecedents and consequences.

2.1Antecedents of satisfactionTrust and commitment are the main relational block (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). They are different concepts, albeit closely related. Trust is the conviction that the other party in the relationship will manage the business with the intention of ensuring beneficial results for both parties (Hung, Cheng, & Chen, 2012). It is the degree to which a company considers that its partner is honest as it indicates the perception of goodwill that the member has (Bowden, 2009). Both constructs have been also proposed as antecedents of satisfaction (e.g. Ferro, Padin, Svensson, & Payan, 2016; Rodríguez del Bosque, Collado Agudo, & San Martín Gutiérrez, 2006), and literature also specify the direct relationship of trust on satisfaction (e.g. Berenguer-Contrí et al., 2020; Farrelly & Quester, 2005; Nyaga, Whipple, & Lynch, 2010).

However, commitment is the willingness of a member to establish and continue a long-term relationship with another member and can include emotional or psychological attachment (Sung & Choi, 2010). It represents the belief that the parties are linked in the long term thanks to the trust and the desire to maintain the relationship. Commitment can have an affective character, related to the feeling of loyalty and emotional attachment, or a calculating character, related to objective reasons such as switching costs or the scarcity of alternatives (Marshall, 2010).

Trust and commitment share that the objective of the members is to achieve a successful relationship (Gupta, Pansari, & Kumar, 2018) so both constructs must coexist. Trust is a clear antecedent of commitment (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). A trust relationship is a condition for there to be a commitment that can guarantee satisfaction and subsequent retention (Fang et al., 2014). This implies that the parties in a relationship may commit to the future of that relationship if there is trust:

H1. The trust that a tourism company has with its supplier positively influences its commitment to the relationship.

Although some authors point out that satisfaction predicts trust and commitment in some way (e.g. Theron et al., 2011), it is generally shared in the literature that they are key antecedents in opinions based on satisfaction (Nyaga et al., 2010; Roberts-Lombard et al., 2017).

Trust is an important predictor of satisfaction as it is key in the relational strategy between companies (Fang et al., 2014). It clearly influences expectations and, therefore, will contribute to satisfaction (Salleh, 2016). A company will choose the supplier that offers the greatest trust in its business. Furthermore, trust-based satisfaction influences the intention to buy again and long-term profitability (Yeung, Ramasamy, Chen, & Paliwoda, 2013). Therefore, it is assumed that trust will influence satisfaction:

H2. The trust that a tourism company has with its supplier positively influences satisfaction with the relationship.

The relationship marketing literature also shares the view that commitment is a clear antecedent of satisfaction (Johnson, Sividas, & Garbarino, 2008). The degree to which a company feels committed to its supplier helps to strengthen the relationship because its influence ensures that the experience is satisfactory (Chang, Tsai, Chen, Huang, & Tseng, 2015). A high level of commitment makes the relationship more stable and generates greater satisfaction (Kaur, Sharma, & Mahajan, 2012):

H3. The commitment that a tourism company has with the relationship positively influences satisfaction with that relationship.

Switching costs can also exert some indirect influence on the satisfaction process. They are defined as “costs perceived, anticipated, and/or experienced by a buyer when changing a relationship from one seller to another” (Pick & Eisend, 2014, p. 186). They are related to the possible loss of benefits and accumulated advantages that a change of supplier would entail. In B2B relationships, companies perceive certain switching costs that can affect their commitment as they influence the decision to choose between continuing the relationship with the supplier or switching to another. Various studies carried out on services support the contribution that switching costs have on commitment (e.g. Gustafsson, Johnson, & Roos, 2005; Ojeme et al., 2018). Therefore, it is assumed that switching costs influence satisfaction in some way through commitment:

H4. The switching costs perceived by the tourism company have a positive influence on the commitment to the relationship.

2.2Consequences of satisfactionDigitisation and globalisation have brought about significant changes (De Leon & Chatterjee, 2017) that require the incorporation of new approaches to explain satisfaction and loyalty processes in the B2B context. This business reality is reflected in recent contributions that shift the interest of responses to satisfaction towards behavioural responses linked to relationship continuity, coordination or cooperation between the parties (Payan, Hair, Andersson, & Awuah, 2016).

Amongst these variables, value co-creation is a novel concept that emerged at the beginning of this century, more focused on B2C environments than B2B (Monteiro D'Andrea, Rigon, Lopes de Almeida & da Silveira Filomena, 2019), but with more logical foundations in industrial contexts (Bolton, Smith, & Wagner, 2003). Value co-creation is based on the concept of value (Gallarza, Gil, & Holbrook, 2011) and the difference lies in the level of participation of the parties. The scarce literature that does exists on co-creation highlights that it is a dynamic process of a collaborative nature where the parties work in partnership to jointly create a superior value (Ranjan & Read, 2016). It is a synergistic interaction because it involves jointly achieving a positive benefit for the parties that a party could not achieve on its own (Zhang et al., 2015). Although there is evidence that value co-creation influences satisfaction (Berenguer-Contrí et al., 2020), satisfaction could be expected to have a certain effect on actions aimed at value co-creation between the parties since the desire to collaborate to obtain benefits for members is only possible if both parties are satisfied. Therefore, we suppose that satisfaction is an antecedent of value co-creation:

H5. The satisfaction of the tourism company with the relationship positively influences the value co-creation.

In addition to value co-creation, the literature attempts to advance knowledge of B2B relationship management based on the basic requirements of a solid relationship, such as continuity and coordination (Payan et al., 2016; Theron et al., 2011).

Continuity is not a new concept, it is linked to loyalty, with the commitment to continue being key to the success of the relationship (Gaurav, 2016). Heide and John (1990, p. 25) define continuity as “the perception of the bilateral expectation of future interaction”. Therefore, continuity is not the perception of the past duration of the relationship, but of the future duration, nor is it the perception that one party has of the desire to continue the relationship, but both parties. In short, it represents the attitude of a company towards the expectation of future interaction between members.

The contributions suggest that this perception of continuity will be conditioned by satisfaction. The literature highlights that satisfaction is an important indicator of channel effectiveness and a predictor of long-term business continuity (Ferro et al., 2016). Satisfaction is key in the decision to maintain the relationship in a B2B context, as it is a clear antecedent of continuity in the construction of a relationship (Palmatier, Dant, Grewal, & Evans, 2006). This implies that the desire of the parties to continue the relationship will depend on the satisfaction that one member has with the other. Roberts-Lombard et al. (2017) confirm that satisfaction contributes to continuity, understood as the future duration of the relationship:

H6. The satisfaction of the tourism company with the relationship positively influences the continuity of said relationship.

Satisfaction can also be a necessary factor for there to be coordination between the parties. Coordination refers to the participation between organisations in joint activities related to structure or process (Keung, Shing, Alison, & Hon, 2015). It is a key factor in ensuring efficiency and obtaining results, helps reduce conflicts and disagreements between parties and allows relationships to be fluid. It is widely agreed that coordination can only be guaranteed if an optimal level of satisfaction is reached and that satisfaction with the relationship strengthens the need to improve cooperation between the parties. Along these lines, satisfaction can be considered as an antecedent of coordination (Palmatier et al., 2006; Roberts-Lombard et al., 2017).

Coordination between the parties must be extended to the new business reality, including the role of ICT in the competitiveness of companies and in the success of B2B relationships (Berné, García-González, García-Uceda, & Múgica, 2015; Daulatkar & Sangle, 2016). Although technologies can limit certain emotional benefits of the relationship, there are many advantages that they provide, such as reducing costs, increasing market share, improving efficiency or helping to achieve competitive advantages, etc. (Huo, Zhang, & Zhao, 2015).

Most research in the tourism context addresses the positive effect that the use and adoption of ICT has on relationships between companies (Berné et al., 2015; Ruiz-Molina, Gil-Saura, & Moliner-Velázquez, 2010), but not the degree of ICT coordination. Following the approach of Roberts-Lombard et al. (2017), the participation and joint work of the parties so that ICTs improve results would depend on the level of satisfaction that the members have. Therefore, it is assumed that satisfaction will have a significant influence on ICT coordination:

H7. The satisfaction of the tourism company with the relationship positively influences the ICT coordination.

Fig. 1 shows the proposed theoretical model

3Methodology3.1Questionnaire and data collectionA quantitative investigation has been carried out through a structured questionnaire. The scales were adapted from previous studies in industrial settings (see Appendix). Items were measured with 7-point Likert scales, from 1: strongly disagree to 7: strongly agree.

To carry out the study, travel agencies from Spain were evaluated. The database of companies in the sector was obtained from lists already prepared for the purposes of previous studies. This information was updated and completed with the ALIMARKET and DUNS 100.0000 databases. In this way, a list of 900 travel agencies in the autonomous communities of Catalonia, Valencia and Madrid was drawn up. 833 agencies were contacted, obtaining a total of 256 valid interviews (77: Barcelona, 102: Valencia, 77: Madrid), with a response rate of 30.73%. The contact process (up to 3 attempts) was carried out initially by telephone, making an appointment to administer the questionnaire in person or by telephone, or giving the alternative option to access the questionnaire online. The key informant was the travel agency manager or supervisor (see Table 1).

Sample profile.

The theoretical model was tested by applying partial least squares (PLS) estimation (Ringle, Wende, & Becker, 2015). Following the recommendations of Henseler, Ringle, Sinkovics, Sinkovics, and Ghauri (2009), bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples of identical size was used to determine the significance of the estimates, generating standard errors and t-value statistics.

The measurement model estimation, taking into consideration all the reflective constructs, allowed us to evaluate the internal consistency of the measurement scales using Cronbach's Alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) coefficients, and by means of the variance extracted from each of the scales (AVE). Table 2 shows the reliability values, which are higher than the minimum thresholds of 0.7 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Nunally, 1978), and AVE values that exceed 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Descriptive statistics, reliability indexes and discriminant validity.

SD: Standard Deviation; CR: composite reliability; AVE: average variance extracted.

The elements of the main diagonal represent the square root of the AVE. HTMT ratios are above the diagonal and correlations are under the diagonal.

The scales validity was contrasted: (1) content validity, since the scales are formed from the adaptation of items according to the bibliographic review; (2) convergent validity, verifying that the factor loadings were significant at 99% (t-Student statistic> 2.58) (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988); and (3) discriminant validity, since the linear correlation between each pair of scales is less than the square root of the AVE of the scales involved (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). This validity was analysed in detail using the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015), showing that the highest ratio between correlations reached 0.744 between continuity-commitment, below the maximum allowed threshold of 0.9 (see Table 2) .

Finally, it was found that there were no common-bias problems in the data. Based on the proposal of Kock and Lynn (2012), the variance inflation factors were calculated (VIFtrust=1.90; VIFcommitment= 2.19; VIFsw_costs=1.52; VIFsatisfaction=2.13; VIFvalue_co-creation=2.08; VIFrelation_continuity=2.36; VIFICT_coord=1.29), all of which were below the maximum threshold of 3.3.

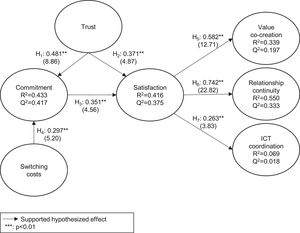

4ResultsA structural equation model was estimated, using the one-tailed test to check the direction of the research hypotheses (Kock, 2014). Table 3 shows the estimated paths coefficients with its t-value associated. Following Aguirre-Urreta and Rönkkö (2018), percentile-based confidence intervals were also performed to evaluate the estimations obtained. The model shows adequate explanatory capacity (Chin, 1988) since determination coefficients are larger than 0.33 (R2Commitment=0.433; R2Satisfaction=0.416; R2Value_co-creation=0.339; R2Relationship_continuity=0.550), except the coefficient associated to ICT coordination (R2ICT_coordinatio=0.069). In addition, the predictive capacity is evaluated through Q2 Stone-Geiser test, being greater than 0 for all endogenous latent variables (Q2Commitment=0.417; Q2Satisfaction=0.375; Q2Value_co-creation=0.197; Q2Relationship_continuity=0.333; R2ICT_coordinatio=0.018).

Path coefficients (causal relationships estimations).

CI: Bias-Corrected Accelerated Bootstrap Confidence Interval;.

f2:effect size (0.02 ≤ f2 < 0.15: small; (0.15 ≤ f2 < 0.35: medium; f2≥0.35: large) (Cohen, 1988).

The results show that both the trust of the tourism company towards its main supplier and the switching costs have a significant effect on commitment (γ = 0.481**; t = 8.861, and γ = 0.297**; t = 5.197) confirming H1 and H4. Furthermore, satisfaction depends significantly on trust (β = 0.371**; t = 4.874) and commitment (β = 0.351**; t = 4.561), demonstrating support for H2 and H3.

In relation to the estimations of satisfaction with the three consequences proposed, the results indicate that there is a significant and positive effect of satisfaction on value co-creation (β = 0.582**; t = 12.707), relationship continuity (β = 0.742**; t = 22.818) and ICT coordination (β = 0.263**; t = 3.830). Therefore, H5-H7 are supported.

Fig. 2 shows graphically the estimations of our theoretical model

5Discussion and conclusions5.1ConclusionsThe results obtained allow us to contrast the proposed model on the satisfaction process in the B2B context, confirming the relationships that satisfaction has with its antecedents and consequences.

With regard to the antecedents, trust, commitment and switching costs have behaved as antecedents of satisfaction. Trust and commitment exert a direct influence on satisfaction while switching costs do it indirectly through commitment. These results are in line with some studies that reveal that trust and commitment are antecedents of satisfaction (Nyaga et al., 2010; Roberts-Lombard et al., 2017) and that switching costs contribute to commitment (Gustafsson et al., 2005; Ojeme et al., 2018). Therefore, the satisfaction that the tourism company feels towards the relationship with its supplier will be conditioned by trust, commitment and the perception of the switching costs.

Regarding the consequences of satisfaction, the results indicate that satisfaction positively influences value co-creation, the continuity of this relationship and ICT coordination. Considering these three constructs responds to the recent interest in the literature to analyse responses to satisfaction that go beyond traditional loyalty, that is, behaviours closely linked to achieving a benefit for both parties in the relationship (Payan et al., 2016). Both value co-creation (Zhang et al., 2015) and relationship continuity (Palmatier et al., 2006) are responses that can only develop if both parties are satisfied. In the same way, ICT coordination, which implies a certain degree of collaboration and joint work by the parties to improve results, will also depend on the satisfaction of the partners (Roberts-Lombard et al., 2017).

5.2Theoretical implicationsThis work makes it possible to advance in the process of building relationships between tourism companies. In the B2B context of this sector, research on the effects of different relational variables is scarce and our work has provided clear evidence of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction. Just as there are contributions on the roles of certain antecedents of satisfaction in B2B in services, such as trust or commitment (e.g. Nyaga et al., 2010), no empirical evidence has been found in regard to the consequences of satisfaction that delve into the relationship between tourism companies, such as value co-creation or ICT coordination. Our contribution, therefore, consists in offering a global model that brings together different relational variables that are rarely addressed in the tourism literature and that could be applicable to other tourism services.

5.3Practical implicationsThis work contributes to improving the management of relationships between tourism companies. On the one hand, service providers must recognise that in order to improve the experiences of their client partners and make them more satisfactory, it is necessary to focus their efforts on improving trust and commitment to the relationship. Trust can be reinforced with actions aimed at conveying a sense of security, honesty and goodwill in the future of the relationship. Commitment can be improved by working on switching costs, that is, increasing the perception of loss of benefits and advantages if a change of provider takes place.

On the other hand, supplier companies must also be aware that the success of the relationship with their clients will depend on their ability to identify the behaviours that strengthen this relationship. If satisfaction influences value co-creation, relationship continuity and ICT coordination, the provider must develop actions that promote joint participation and collaboration, that generate positive expectations of a future relationship and that favour the coordination of technologies. All this in order to achieve a benefit for both parties and a higher value in the service that would not be possible if acting independently.

It must be also aware that tourism sector continues being one of the most affected in the current post-crisis stage (Sigala, 2021), to the extent that COVID-19 has led to the collapse of the industry (Cambra-Fierro, Fuentes-Blasco, Gao, Melero-Polo, & Trifu, 2022). There are already studies that indicate how companies should manage their relationships, implementing a more selective approach towards those that are more promising. For example, Mitręga and Choi (2021) advocate prioritizing the entire chain of relationships, since it will be more than beneficial in the long term. In this sense, tourism agencies must be accepted that not all their suppliers may survive in the current period of uncertainty. Mora-Cortez and Johnston (2020) identify four key areas in which technological development stands out as a priority. As we have exposed, ICT provide many advantages to improve the relationship such as reducing costs and augmenting efficiency (Huo et al., 2015).

6Limitations and future researchThis work is not without limitations that represent interesting challenges in order to advance in this line of research. The tested model has only been applied to one type of tourism company (travel agencies, mostly retailers) evaluating their relationship with the most prominent providers of accommodation services (mainly hotels and wholesale agencies). This issue, together with the difficulties of accessing a larger and more representative sample, typical of the B2B context, have prevented the generalisation of the results to other sectors related to tourism. Therefore, we propose to replicate this study in other tourism companies, also closely linked to technologies such as the hotel sector, restaurants or cultural services, obtaining a larger sample.

Regarding the measurement of the constructs, although the relational variable scales applied to the B2B context are scarce, we also propose the use of other measures that more rigorously reflect the true nature of the analysed constructs.

Finally, empirical research has focused on analysing the satisfaction process solely from the point of view of the client partner (or buyer). Given that the valuations and perceptions that buyers have can differ significantly from those of their suppliers, it would be interesting to test the model by addressing all the constructs from both perspectives: buyer and supplier. In addition to this new approach, the mediating role of satisfaction could also be analysed by studying the direct and indirect effects of the antecedents on the consequences.

Author contributionsAll authors have contributed equally.

This research has been developed within the framework of the research project funded by the State Research Agency of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Reference no.: PID2020-112660RBI00/ AEI / 10.13039 / 501100011033), the Funding for Consolidated Research teams of the Regional Council of Innovation, Universities, Science and Digital Society (Reference no.: AICO2021/144/GVA) and the Funding for Special Research Actions of Universitat de València (Reference no.: UV-INVAE-1553911).

| Constructs | Sources | Items | λ (t-Stat) |

| Trust | Ferro et al. (2016) | We can rely on this supplier to keep promises made to us | 0.938** (32.85) |

| We are not hesitant to do business with this supplier even when the situation is vague | 0.815** (86.81) | ||

| This supplier is trustworthy | 0.861** (32.97) | ||

| Commitment | Morgan and Hunt (1994) | We are very committed to the relationship with this supplier | 0.858** (35.77) |

| We have a strong sense of loyalty to this supplier | 0.888** (53.11) | ||

| We intend to maintain this relationship indefinitely | 0.851** (36.31) | ||

| This relationship deserves our firm's maximum effort to maintain | 0.886** (46.95) | ||

| Switching costs | Ad-hoc | The time I need to make arrangements with this supplier is adequate | 0.706** (14.10) |

| This supplier takes away problems | 0.762** (20.45) | ||

| Little effort is required to make arrangements with this supplier | 0.774** (17.87) | ||

| Patterson and Smith (2001) | Considering all things, I would waste a lot of time if I change suppliers | 0.859** (40.27) | |

| I will loss a friendly and comfortable relationship if I change | 0.762** (26.40) | ||

| If I change there is a risk the new one supplier won't be as good | 0.828** (25.79) | ||

| Satisfaction | Geyskens and Steenkamp (2000) | My relationship with this supplier has provide me with a dominant and profitable market position in my sales area | 0.817** (42.16) |

| I am very pleased with my decision to distribute this supplier's products since their high quality increases customer traffic | 0.805** (28.61) | ||

| The marketing policy of this supplier helps me to get my work done effectively | 0.712** (13.37) | ||

| Interactions between my firm and this supplier are characterized by mutual respect | 0.755** (15.81) | ||

| I am satisfied with the overall working relationship | 0.847** (39.67) | ||

| If I could do it again, I would choose this supplier's product line rather than another competing supplier's product line | 0.861** (42.51) | ||

| Value co-creation | Claro and Claro (2010); Zhang et al. (2015) | Our company plans the new products and services together with this supplier | 0.875** (45.90) |

| Our company shares long-term plans of our products with this supplier | 0.895** (39.59) | ||

| This supplier and our company deal with problems that arise in the course of the relationship together | 0.714** (17.11) | ||

| In most aspects of the relationship with this supplier, the responsibility for getting things done is shared | 0.839** (29.68) | ||

| Relationship continuity | Bloemer, De Ruyter and Wetzels (1999) | We would continue to do business with this supplier if its prices increase somewhat | 0.837** (31.30) |

| Although there are other similar suppliers, we prefer this one | 0.871** (46.62) | ||

| Probability of continuing with this supplier the next time we need these services | 0.752** (16.84) | ||

| ICT coordination | Wu, Yeniyurt, Kim and Cavusgil (2006) | We work with our provider to align the ICT | 0.976** (27.94) |

| We coordinate the improvements in ICT for best performance | 0.974** (27.85) | ||

| λ: standardized factor loading; t-Stat: t-statistic value**: p < 0.01 | |||