Ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy is considered the technique of choice for the histological diagnosis of space-occupying lesions, given its high level of safety and diagnostic performance. However, since it is an invasive diagnostic procedure, complications can occur. Various clinical and radiological parameters have been analysed as factors related with the efficacy of the technique or with its complications; however, the results have been contradictory. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the impact of various risk factors on the efficacy and complications of ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy in the diagnosis of space-occupying lesions in ordinary clinical practice.

Material and methodsThis retrospective observational study included all patients who underwent real-time ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsies of space-occupying liver lesions with the free-hand technique between December 2012 and February 2018 in the diagnostic imaging department at the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela.

We analysed the following risk factors: location of the lesion in upper liver segments (II, IVa, VII, or VIII); proximity to the liver capsule, distance from the skin >100mm, interposition of osseus or vascular structures, inability to go through healthy parenchyma, and lack of patient cooperation during the procedure.

Efficacy was analysed in terms of the number of cylinders obtained and the percentage of adequate biopsies; safety was analysed in terms of the percentage of complications, which were classified as major or minor.

ResultsWe included 295 biopsies in 278 patients (median age, 69 years; 64.1% male; 44.7% had prior neoplasms). In 61.4%, the biopsy was indicated for the initial diagnosis; 82.4% of biopsies were done in hospitalised patients, and 65% of the lesions were located in the right liver lobe.

The median number of cylinders obtained was 3 (range 1–6); 91.2% of the biopsies were adequate and 92.2% were considered clinically useful. These percentages did not differ significantly according to the presence of risk factors. Complications occurred in 10 (3.4%) patients. Complications were considered major in 3 (0.9%) patients (2 (0.6%) bleeding complications and 1 (0.3%) infectious complication) and minor in 7 (2.4%). The percentage of complications was significantly higher in patients who did not cooperate during the procedure (P=.04).

ConclusionsUltrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy is an efficacious and safe technique for the histological diagnosis of space-occupying liver lesions. Our results confirm the increased rate of complications when patients fail to cooperate during the procedure.

La biopsia hepática percutánea ecoguiada se considera la técnica de elección para el diagnóstico histológico de las lesiones ocupantes de espacio (LOE), dada su elevada seguridad y rentabilidad diagnóstica. Sin embargo, al tratarse de una técnica de diagnóstico invasiva, no se encuentra exenta de complicaciones. Diversos parámetros clínico-radiológicos han sido analizados como factores relacionados con la eficacia o complicaciones, con resultados contradictorios. Por todo ello, el objetivo de nuestro estudio es evaluar el impacto de diversos factores de riesgo en la eficacia y complicaciones de la biopsia hepática percutánea ecoguiada en el diagnóstico de LOE, en el ámbito de la práctica clínica habitual.

Material y métodosLlevamos a cabo un estudio observacional, retrospectivo, unicéntrico de pacientes sometidos a biopsia hepática percutánea ecoguiada en tiempo real con técnica de manos libres para el diagnóstico de LOE, realizadas en el Servicio de Radiodiagnóstico del Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela entre diciembre 2012 y febrero 2018. Seleccionamos como factores de riesgo: la localización de la LOE en los segmentos hepáticos superiores (II, IVa, VII y VIII), la proximidad a la cápsula hepática, la distancia entre piel y LOE mayor de 100mm, la interposición de estructuras óseas o vasculares, la incapacidad para atravesar parénquima sano o la falta de colaboración del paciente durante el procedimiento. La eficacia fue analizada en términos de número de cilindros extraídos y porcentaje de biopsias satisfactorias; y la seguridad, en términos de porcentaje de complicaciones presentadas, clasificándolas, a su vez, en complicaciones mayores y menores.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 295 biopsias de 278 pacientes. La mediana de edad fue de 69 años, el 64,1% eran varones y el 44,7% tenía una neoplasia previa. El 61,4% de las biopsias se indicaron para el diagnóstico inicial, el 82,4% se realizaron con el paciente ingresado y el 65% de las lesiones se localizaban en el lóbulo hepático derecho.

La mediana de cilindros extraídos fue de 3 (rango 1–6). El 91,2% de las biopsias fueron satisfactorias, sin diferencias en función de la presencia de factores de riesgo, y el 92,2% fueron clasificadas como útiles desde el punto de vista clínico. Diez (3,4%) pacientes presentaron complicaciones, en 3 (0,9%) fueron complicaciones mayores, en 2 (0,6%) complicaciones hemorrágicas y en 1 (0,3%) complicaciones infecciosas; y los 7 restantes (2,4%), complicaciones menores. Se observó un porcentaje significativamente superior de complicaciones en pacientes no colaboradores durante el procedimiento (P=.04).

ConclusionesLa biopsia hepática percutánea ecoguiada es una técnica eficaz y segura para el diagnóstico histológico de LOE. Se confirma el impacto en el desarrollo de complicaciones en el paciente no colaborador durante el procedimiento de biopsia.

Percutaneous liver biopsy with real-time ultrasound guidance is considered the technique of choice for obtaining diagnostic histological material from space-occupying lesions (SOL), given its good safety profile, efficacy and low cost.1

Due to the advances made in the last decade in genomic and molecular analysis, as well as the appearance of drugs directed against molecular targets, it is necessary to obtain a greater amount of histological material, essential for the diagnosis, therapeutic orientation and detection of biomarkers, and prognostic and predictive factors.2,3 Moreover, the amount of viable tissue and cellularity have been associated with the number of tissue cylinders obtained.4

On the other hand, the use of ultrasound guidance in real time allows for visualising the tip of the needle at all times, which reduces the risk of complications such as pneumothorax, perforation of other viscera or early detection of bleeding. However, as it is an invasive technique, it is not free of complications such as haemorrhage, infection and perforation of the hollow viscus.5,6 Previous studies have reported a mortality of around 0.001%−0.031% and 0.7%–1.4% major complications, among which the most frequent is haemorrhage.7–9

Multiple studies have attempted to identify risk factors related to the efficacy and/or complications of the biopsy. Boyum et al., in an analysis of 6614 ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsies with 0.8% major complications (including 0.1% infections) and 0.0.1% mortality, reported that the presence of less than 50,000 platelets, being of female sex, and the need for more than two biopsy attempts, were associated with a significant risk of complications.8 However, in the study by Malcom et al., which included 1060 diffuse liver and kidney or SOL biopsies, the impact on the percentage of complications of factors such as age, sex, blood pressure, coagulation or final histology was not evidenced.10 Finally, in a study that analysed the impact of various risk factors on the percentage of haemorrhagic complications in 1876 percutaneous liver biopsies, no significant differences were found based on their location (subcapsular vs. non-subcapsular), the type of biopsy (fine needle aspiration puncture [FNAP] vs. core needle biopsy), the size of the needle or the number of passes.9,11–13

On the other hand, regarding the predictive factors of efficacy, the bibliography is scarce. Only one study is available, in which, based on 3085 percutaneous liver biopsies, data from 78 repeated biopsies (2.5%) were analysed, of which 83.3% were successful biopsies, 10.6% had minor complications, and there were no major complications or associated deaths. Nor were any significant differences in efficacy observed depending on the size, depth, segment or number of passes.5,14

Therefore, the objective of our study is to evaluate the impact of various risk factors on the efficacy and complications of ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy in the diagnosis of SOLs, in the context of routine clinical practice.

Material and methodsStudy designWe carried out an observational, retrospective, single-centre study, which included patients who had undergone an ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy, performed with real-time ultrasound guidance and a free-hand technique for the diagnosis of SOLs within the scope of routine clinical practice. The biopsies were carried out in the Radiodiagnosis Service of the University Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela, in the period between December 2012 and February 2018, and the patients had given their consent. Patients unable to understand the study procedures and sign the informed consent, those who lacked all the clinical-pathological data and those who underwent techniques other than real-time ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy and free-hand technique for the diagnosis of SOLs, such as liver FNAP, non-ultrasound-guided diffuse liver biopsy or transjugular biopsy, were excluded.

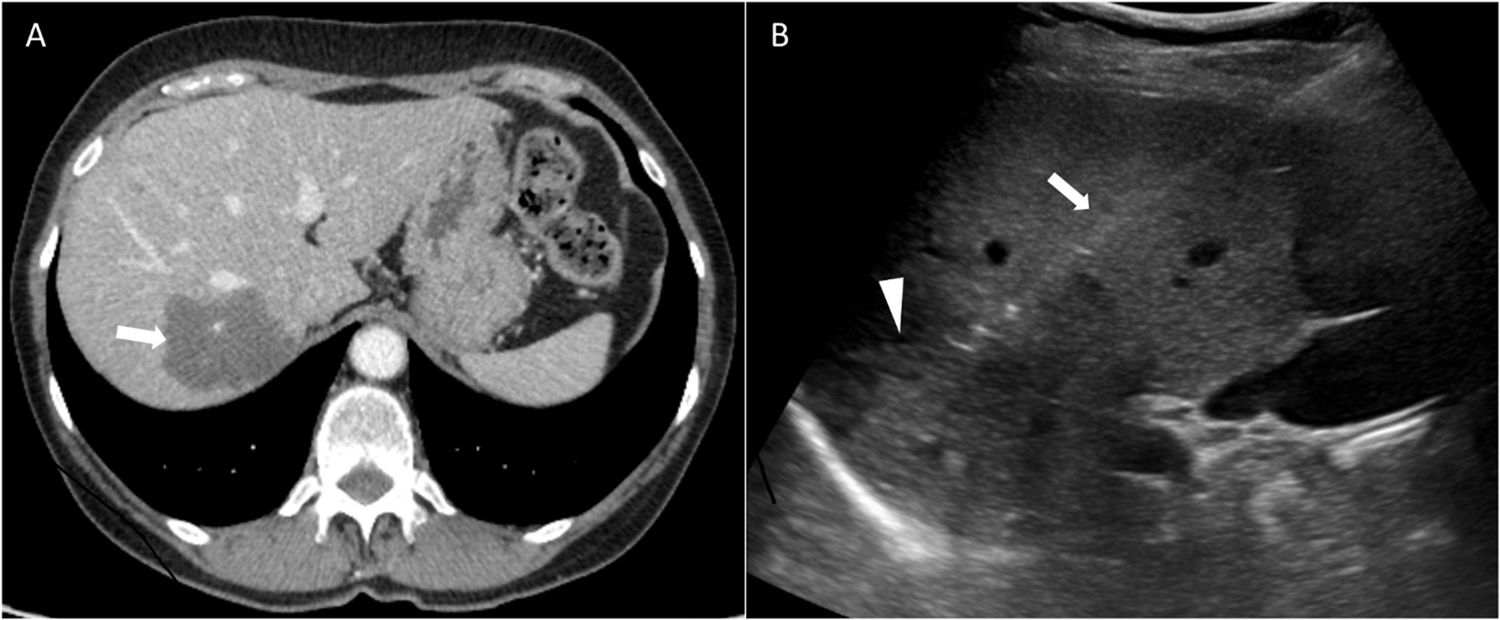

Biopsy procedureUltrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy with free-hand technique and real-time ultrasound guidance is the technique of choice at our centre for the histological diagnosis of SOLs in routine clinical practice. For this reason, in all percutaneous liver biopsies of SOLs included in our study, the free-hand technique and real-time ultrasound guidance were always used, and they were performed within the scope of routine clinical practice (Fig. 1). Furthermore, they were performed by a single radiologist expert in interventional ultrasound, in accordance with the competence in vascular and interventional radiology guidelines of the Sociedad Española de Radiología Vascular e Intervencionista (SERVEI) [Spanish Society of Vascular and Interventional Radiology], the Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica (SERAM) [Spanish Society of Medical Radiology], the Sociedad Española de Gestión y Calidad en Radiología (SEGECA) [Spanish Society of Management and Quality in Radiology] and their quality standards.15

In accordance with the main clinical practice guidelines, treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiaggregants or anticoagulants was suspended 7 days before the biopsy and their replacement with low molecular weight heparin up to 24h before the procedure was left to the discretion of the treating clinician. Meanwhile, all patients with non-correctable coagulopathy, defined by the presence of less than 50,000 platelets or an international normalised index greater than 1.5, and which could not be corrected before performing the biopsy, were excluded.

The biopsies were performed under ultrasound guidance (Philips HDI 5000 SonoCT with 4.5MHz multi-frequency convex probe). In the biopsies performed by direct puncture technique, we used a tru-cut or lateral cut, semi-automatic, 18 gauge, 150mm long needle (SpeedyBell, Biopsybell, Mirandola, Italy). In the coaxial biopsies, a coaxial puncture set consisting of a biopsy needle, as described above, and a coaxial needle (SpeedyBell & introduttore, Biopsybell, Mirandola, Italy) was used. Regarding the choice of puncture technique, it should be noted that, due to the absence of conclusive studies on the technique of choice, the radiologist used both techniques interchangeably.

Regarding the context of the biopsies performed, they were performed either with patients hospitalised or on an outpatient basis. The minimum observation period was 6h. In the biopsies performed in hospitalised patients, due to the logistics at our centre, vital signs were periodically monitored for the first 10h after the procedure, maintaining absolute rest for 8h, the first 2 in the right lateral decubitus position. In outpatient biopsies, the patient remained under hospital surveillance for the first 6h, after which home surveillance was continued under the supervision of a responsible adult.

The results of the biopsies were classified, based on the pathological results obtained, as “satisfactory” if the material obtained allowed a definitive diagnosis to be established; “insufficient material” if a sample had been taken from the lesion, but this was insufficient for an accurate diagnosis; or “failed” if the tissue obtained did not come from the lesion.

Biopsies were categorised according to their final clinical utility as: initial diagnosis of malignancy, confirmation of metastatic disease, identification of a second neoplasm, determination of the origin of metastatic disease in a patient with a history of 2 or more previous neoplasms, exclusion of malignancy, molecular studies, and inconclusive if they lacked clinical utility for the patient.

All complications recorded in the patient's medical history were registered within 72h after the procedure. Major complications were classified as those that required interventional measures, such as transfusion of blood products, embolisation or surgery, and minor complications as those that resolved spontaneously with conservative measures, such as fluid therapy and analgesia.

Patient- and/or lesion-related clinical-radiological parameters that had previously been tested as predictive factors of efficacy and/or complications were included: location of the SOL in the upper liver segments (II, IVa, VII and VIII), proximity to the liver capsule, distance between the skin and the SOL greater than 100mm, interposition of bone or vascular structures, inability to traverse healthy parenchyma or lack of patient collaboration during the biopsy.

Statistical aspectsThe study was carried out using the statistical software SPSS version 25. Qualitative variables were analysed descriptively using frequency or percentages, and for quantitative variables the mean and standard deviation, median and range were determined. For the comparison of variables, the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used, depending on the sample size of the different subgroups, considering an association between variables as significant if it was less than 0.05.

Ethical and legal aspectsThis study has been carried out in accordance with the rules of good clinical practice and current regulations, including Law 14/2007, the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Oviedo Convention. Regarding data protection, Organic Law 15/1999 and its implementing regulation Royal Decree 1720/2007, have been complied with. Prior to conducting the study, authorisation was obtained from the corresponding research ethics committee. All patients gave their informed consent.

ResultsCharacteristics of the sample populationA total of 295 biopsies taken between December 2012 and February 2018 from 278 different patients were included. The characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample population.

| Characteristics | Total, N=295 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range) | 69 (33−88) |

| >70 years | 133 (45.1%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 189 (64.1%) |

| Female | 106 (35.9%) |

| Previous neoplasia | |

| Yes | 132 (44.7%) |

| No | 163 (55.3%) |

| Indication for biopsy | |

| Initial diagnosis | 182 (61.7%) |

| Confirmation of metastasis | 105 (35.6%) |

| Molecular study | 8 (2.7%) |

| Biopsy context | |

| Inpatient | 243 (82.4%) |

| Outpatient | 52 (17.6%) |

| Puncture technique | |

| Direct | 142 (48.1%) |

| Coaxial | 153 (51.9%) |

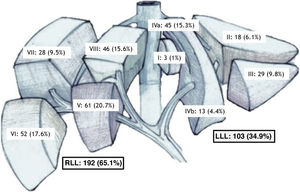

| Liver lobe | |

| Right | 192 (65.0%) |

| Left | 103 (35.0%) |

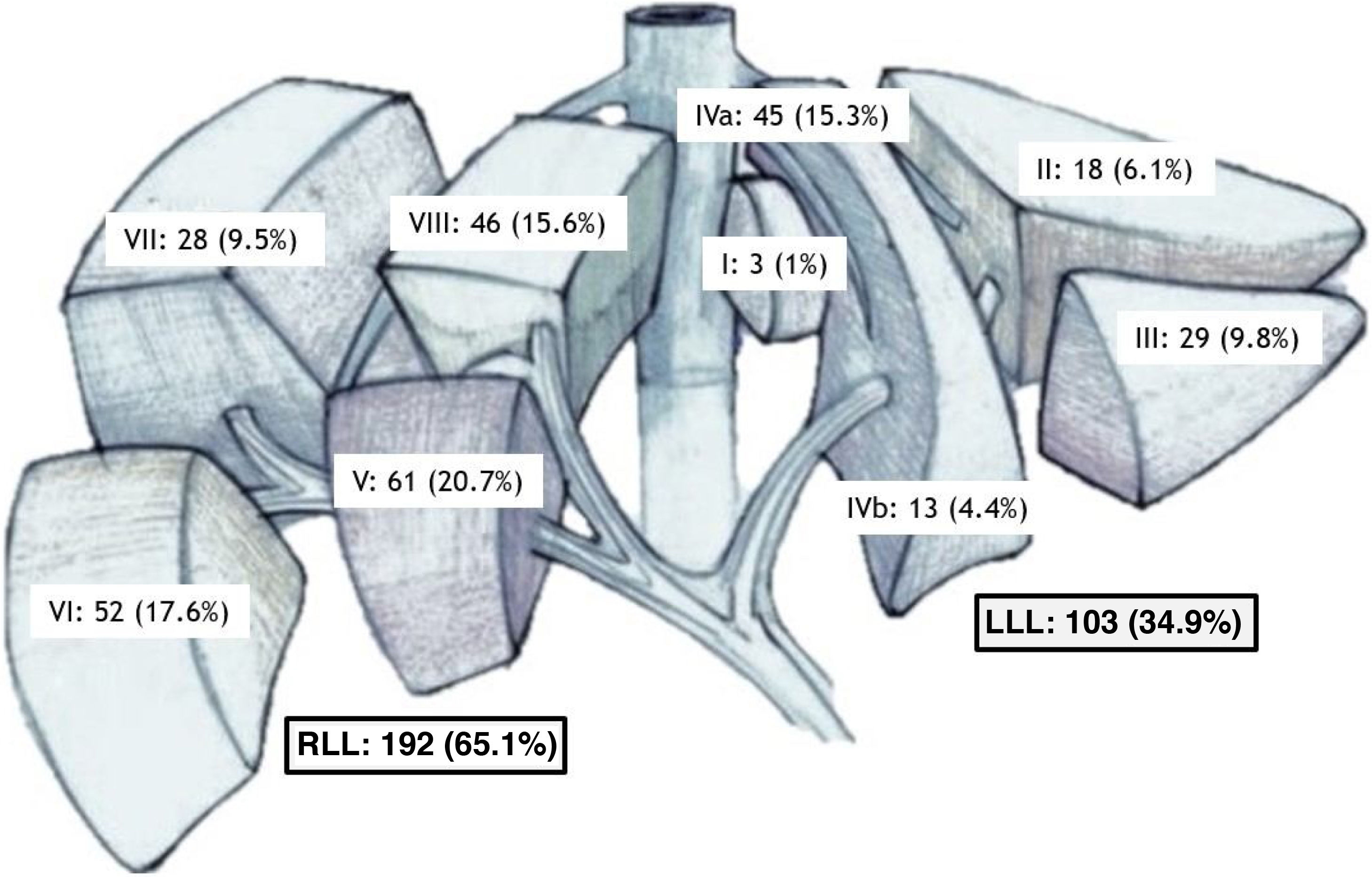

| Liver segment | |

| I | 3 (1.0%) |

| II | 18 (6.1%) |

| III | 29 (9.8%) |

| IVa | 45 (15.3%) |

| IVb | 13 (4.4%) |

| V | 61 (20.7%) |

| VI | 52 (17.6%) |

| VII | 28 (9.5%) |

| VIII | 46 (15.6%) |

The median age was 69 years (range 33−88 years) and 64.1% were male. Regarding personal history, 7.9% received antiplatelet treatment, 7.6% were on anticoagulant treatment, 4.3% had liver disease (defined as the presence of liver cirrhosis and/or infection by virus B or C), and 3.4% had pathologies that made collaboration difficult during the procedure, such as moderate-severe COPD or certain neurological pathologies. Of the total number of biopsies, 44.7% had a history of a previous neoplasm.

Over half (61.7%) were indicated for the initial diagnosis, and 82.4% were performed in hospitalised patients. Overall, 51.9% were carried out using the coaxial puncture technique. The SOLs were located mainly in the right liver lobe (65.1%), especially in segments V (20.7%) and VI (17.6%) (Fig. 2).

Efficacy and complications of biopsiesThe median number of cylinders extracted was 3 (range 1–6). In 6 patients (2%) 1 cylinder was obtained; 2 cylinders in 44 biopsies (14.9%); 3 cylinders in 200 biopsies (67.8%); 4 cylinders in 40 biopsies (13.6%); 5 cylinders in 4 procedures (1.4%), and in 1 procedure (0.3%) 6 cylinders were obtained. Thus, in 83.1% of the biopsies 3 or more cylinders were obtained.

Regarding the overall efficacy of the biopsies, 269 (91.2%) were labelled as “successful”, 19 (6.4%) as “failed,” and 7 (2.4%) as “insufficient material”. If we break down the overall efficacy per patient, of the 278 patients, 255 (91.7%) obtained a satisfactory biopsy, 16 (5.8%) a failed biopsy and 7 (2.5%) a biopsy with insufficient material, after performing a first biopsy. After performing a second biopsy in 9 patients (1 of the 7 patients with insufficient material and 8 of the 16 with a failed biopsy), 6 patients obtained a satisfactory biopsy, which means that, in total, 261 (93.8%) patients obtained a successful biopsy after a second attempt. From a clinical point of view, 92.2% of the biopsies were classified as useful. The final utility of the biopsies is broken down in Table 2.

Final utility of biopsies.

| Final utility of biopsies | N=1295 (%) |

|---|---|

| Initial diagnosis | 133 (45.1%) |

| Confirmation of metastatic disease | 58 (19.7%) |

| Identification of second neoplasm | 15 (5.1%) |

| Determination of the origin of metastasis in a patient with more than 2 previous neoplasms | 8 (2.7%) |

| Ruling out malignancy | 28 (9.5%) |

| Molecular study | 2 (0.7%) |

| Inconclusive | 23 (7.8%) |

No patient died as a result of the biopsy. Ten patients (3.4%) presented complications in the 72h after the biopsy. Of these, 3 patients (0.9%) presented major complications: 2 (0.6%) had haemorrhagic complications that required transfusion of blood products, and 1 (0.3%) had infectious complications that required drainage and intravenous antibiotic therapy. The remaining 7 patients (2.4%) had minor complications in the form of pain, which was treated with first-stage analgesics and resolved completely 24h after the procedure (Table 3).

Impact of risk factorsWe identified 54.5% of SOLs located in the upper liver segments, 69.5% of lesions close to the liver capsule, 8.5% of SOLs with interposition of vascular or bone structures in the puncture tract, 14.2% of lesions more than 100mm from the percutaneous access, 3.4% of patients that were non-cooperative during the procedure, and 24.1% of procedures with an inability to traverse healthy liver parenchyma.

No significant differences were observed in the percentage of successful biopsies based on the presence of risk factors such as location in upper liver segments (P=.838), proximity to the liver capsule (P=.116), interposition of vascular structures or bone (P=.995), path between the skin and the lesion greater than or equal to 100mm (P=.774) or absence of patient collaboration (P=.217). We observed a non-significant trend regarding the inability to traverse healthy parenchyma (P=.052).

However, we observed a significant increase in the appearance of complications during the procedure in non-cooperative patients (P=.04), without observing differences in other risk factors, such as lesions located in the upper liver segments (P=.995), proximity to the liver capsule (P=.995), with interposition of vascular or bone structures in the puncture route (P=.989), distance between skin and lesion equal to or greater than 100mm (P=.630) or inability to traverse healthy parenchyma (P=.064) (Table 4).

Impact of risk factors on efficacy and complications. The rest of the footnotes are fine.

| Risk factors | Total N=295 | Satisfactory N=269 | Failed/Insufficient N=26 | P | Complications: No N=285 | Complications: Yes N=10 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| >70 years | 133 (45.1%) | 120 (44.6%) | 13 (50.0%) | .681 | 127 (44.6%) | 6 (60.0%) | .355 |

| <70 years | 162 (54.9%) | 149 (55.4%) | 13 (50.0%) | 158 (55.4%) | 4 (40.0%) | ||

| Liver segment | |||||||

| Upper (II, IVa, VII, VIII) | 134 (45.5%) | 123 (45.7%) | 11 (42.3%) | .838 | 129 (45.3%) | 5 (50.0%) | .995 |

| Lower (I, III, IVb, V, VI) | 161 (54.5%) | 146 (54.3%) | 15 (57.7%) | 156 (54.7%) | 5 (50.0%) | ||

| Proximity to the capsule | |||||||

| Yes | 205 (69.5%) | 183 (68.0%) | 22 (84.6%) | .116 | 198 (69.5%) | 7 (70.0%) | .995 |

| No | 90 (30.5%) | 86 (32.0%) | 4 (15.4%) | 87 (30.5%) | 3 (30.0%) | ||

| Interposition of vascular or bone structures | |||||||

| Yes | 25 (8.5%) | 23 (8.6%) | 2 (7.7%) | .995 | 24 (8.4%) | 1 (10.0%) | .989 |

| No | 270 (91.5%) | 246 (91.5%) | 24 (92.3%) | 261 (91.6%) | 9 (90.0%) | ||

| Distance between skin and lesion | |||||||

| >100mm | 42 (14.2%) | 38 (12.5%) | 4 (15.4%) | .774 | 40 (14.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | .630 |

| <100mm | 253 (85.8%) | 231 (87.5%) | 22 (84.6%) | 245 (86.0%) | 8 (80.0%) | ||

| Collaborating patient | |||||||

| No | 10 (3.4%) | 8 (3.0%) | 2 (7.7%) | .217 | 8 (2.8%) | 2 (20.0%) | .040 |

| Yes | 285 (96.6%) | 261 (97.0%) | 24 (92.3%) | 277 (97.2%) | 8 (80.0%) | ||

| Inability to traverse healthy tissue | |||||||

| Yes | 71 (24.1%) | 69 (25.7%) | 2 (7.7%) | .052 | 66 (23.1%) | 5 (50.0%) | .064 |

| No | 224 (75.9%) | 200 (74.3%) | 24 (92.3%) | 219 (76.9%) | 5 (50.0%) | ||

Thanks to advances in recent decades, ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy represents the technique of choice for the histological diagnosis of SOLs, given its cost-effectiveness and safety. However, the identification of risk factors predictive of efficacy or complications in the context of routine clinical practice continues to be a controversial issue.

In our study, we retrospectively analysed 295 real-time ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsies with free-hand technique in 278 patients. The biopsies were performed by a single radiologist expert in interventional ultrasound in the context of the usual clinical practice at a tertiary hospital.

First, we analysed the clinical-pathological characteristics of our series. The median age of our patients was 69 years, with 45.1% of patients older than 70 years, in line with the data on cancer incidence in our country that place the median age at diagnosis in the seventh decade of life.16

Regarding the context of the biopsies performed, only 17.6% were performed on an outpatient basis. This is due to the fact that, in order to perform the biopsies on an outpatient basis it is essential that the patient resides less than 30min from the hospital, is able to travel there, and is accompanied by a responsible adult for the first 24h after the procedure. These requirements are difficult to achieve in a health area with a large, very dispersed, ageing population with limited socio-economic resources in many cases.

When analysing the puncture technique used, in 51.9% of patients the coaxial puncture was used, compared to 48.1% carried out by direct puncture Due to the lack of conclusive studies indicating the best technique, the radiologist did not follow any specific criteria and used both techniques interchangeably, as shown by the fact that the characteristics of both groups are similar, which does not condition any type of bias. The fact that all the biopsies were performed by a single radiologist, using a standardised procedure and in accordance with SERVEI, SERAM and SEGECA standards minimises the biases related to interpersonal variability, present in multicentre studies, which in many cases can introduce almost imperceptible variations in the procedure.

After characterising our study population, we analysed the efficacy and safety of the biopsies. In the first place, regarding the number of cylinders obtained, we observed that the median was 3, and that 3 or more cylinders were obtained in 83.1% of patients. These data, not previously described, give us an idea of the quality of the biopsies, which make it possible obtain a large amount of histological material.

Regarding the percentage of satisfactory biopsies, 91.2% obtained a satisfactory result overall, data that substantially improve the historical series with sensitivities of around 61%–84%.17

An innovative aspect of our work has been the definition of a classification called “final utility of the biopsy”. This is absent in previously published studies on the efficacy and/or complications of ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy, which have merely focused on technical aspects and that do not analyse the clinical impact of such biopsies. Our study has demonstrated real clinical utility in 92.2% of patients, whether in obtaining an initial diagnosis, confirming metastatic disease, determining the origin of metastatic disease in a patient with a history of several neoplasms, ruling out malignancy or in allowing molecular studies to be completed.

Liver biopsy is a safe technique with a mortality rate of approximately 0.01% in published series. The percentage of serious complications is between 0.5% and 1.7%.8,11,18 Of these, 60% of complications appear in the first 2h after the procedure and between 83% and 96% within the first 24h. Approximately 2%–3% of patients require hospital admission due to complications, of which the most frequent are uncontrolled pain and hypotension.18–20

Regarding the safety of our biopsies, we identified a percentage of complications of 3.4% in the following 72h from the inpatient and/or emergency care records. These include minor complications (such as pain) present in 2.4%, major complications (such as bleeding) in 0.6%, and infectious complications in 0.3%. No deaths related to the procedure were identified.

If we compare our data with previous series, we find that they are practically identical to those published by Malcom et al., who, in a series of 1066 percutaneous liver and kidney biopsies (both diffuse and of SOLs), of which 495 were liver biopsies, identified 0.8% of major complications such as bleeding or infection and 2.4% of minor complications such as pain.10

Regarding the importance of the radiologist's experience, in the series by Malcom et al. a significant increase in major complications was evidenced in radiologists classified as “inexperienced” (2% vs. 0.9%). If we analyse the data from our series, the percentage of major complications is the same as that reported in Malcom's series for expert radiologists. It is important to note that although it is true that SOL biopsies do not require specific training in interventional radiology, it is recommended that they be performed by an expert radiologist in order to minimise the complications associated with them. In our study, in which we selected patient- and/or lesion-related risk factors, we did not observe significant differences in the efficacy of the biopsies, in terms of satisfactory biopsies, based on any of the risk factors analysed. These data are in line with those previously reported.

In relation to the impact of risk factors on the development of complications, we have identified a significant increase in non-cooperative patients during the procedure (P=.004). The increase in complications in non-cooperating patients had already been reported previously, justifying that this increased risk was due to the risk of liver rupture or laceration due to uncontrolled movements of the patient and, consequently, a higher risk of bleeding. For this reason, clinical guidelines have defined it as a contraindication, either absolute or relative, depending on the guideline. In addition, if the indication for a biopsy is essential, it is recommended to administer moderate to deep sedation, or even general anaesthesia.17 Based on these results, we implemented a sedation protocol for non-cooperative patients at our centre, and since then no significant complications have appeared.

Moreover, we have identified a non-significant trend in the impossibility of traversing healthy parenchyma both in terms of efficacy (P=.052) and the appearance of complications (P=.064). It is possible that this could be due to the limited size of our series, which did not allow us to observe differences, if they really existed, which is why it should be studied in larger series.

Finally, our study is not without its limitations. The fact that this is a retrospective, observational, single-centre study in which all biopsies were performed in the context of routine clinical practice, by the same radiologist, and that the choice of the puncture technique was not made randomly, means that we cannot rule out operator-induced bias. In addition, the fact that the complications have been obtained from the patient's medical history means that we cannot rule out information bias, especially in the case of minor complications such as mild pain, in which analgesic treatment was not necessary and, therefore, was not included in the patient's history.

ConclusionsUltrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy is an effective and safe technique for the diagnosis of SOLs. Our series confirms the impact on the development of complications in non-cooperative patients during the biopsy procedure, with no differences in the risk factors related to the lesion itself.

Authorship- 1

Persons responsible for the integrity of the study: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

- 2

Study concept: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

- 3

Study design: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

- 4

Data collection: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

- 6

Statistical processing: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

- 7

Literature search: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

- 8

Drafting of the paper: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

- 10

Approval of the final version: RVP, NML, MVV, JMCV.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We thank Francisco Gude Sampedro from the Epidemiology Unit of the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago for his advice on the methodological aspects of this article.