In imaging studies, some developmental anomalies such as perisplenic accessory spleen are easily recognizable due to their high incidence. However, other, less common anomalies such as intrapancreatic accessory spleen, splenopancreatic fusion, splenogonadal fusion, heterotaxy, and wandering spleen, as well as acquired conditions such as splenosis, can pose diagnostic difficulties. This aim of this review is to show the imaging diagnosis and differential diagnoses of these uncommon splenic anomalies.

En las exploraciones radiológicas abdominales, algunas anomalías del desarrollo, como el bazo accesorio periesplénico, son fácilmente reconocibles debido a su elevada incidencia. Sin embargo, otras menos frecuentes, como el bazo accesorio intrapancreático, la fusión esplenopancreática o esplenogonadal, la heterotaxia y el bazo errante, así como anomalías adquiridas como la esplenosis, pueden plantear dificultades diagnósticas. El propósito de nuestra revisión es mostrar los hallazgos radiológicos y el diagnóstico diferencial de dichas anomalías esplénicas poco habituales.

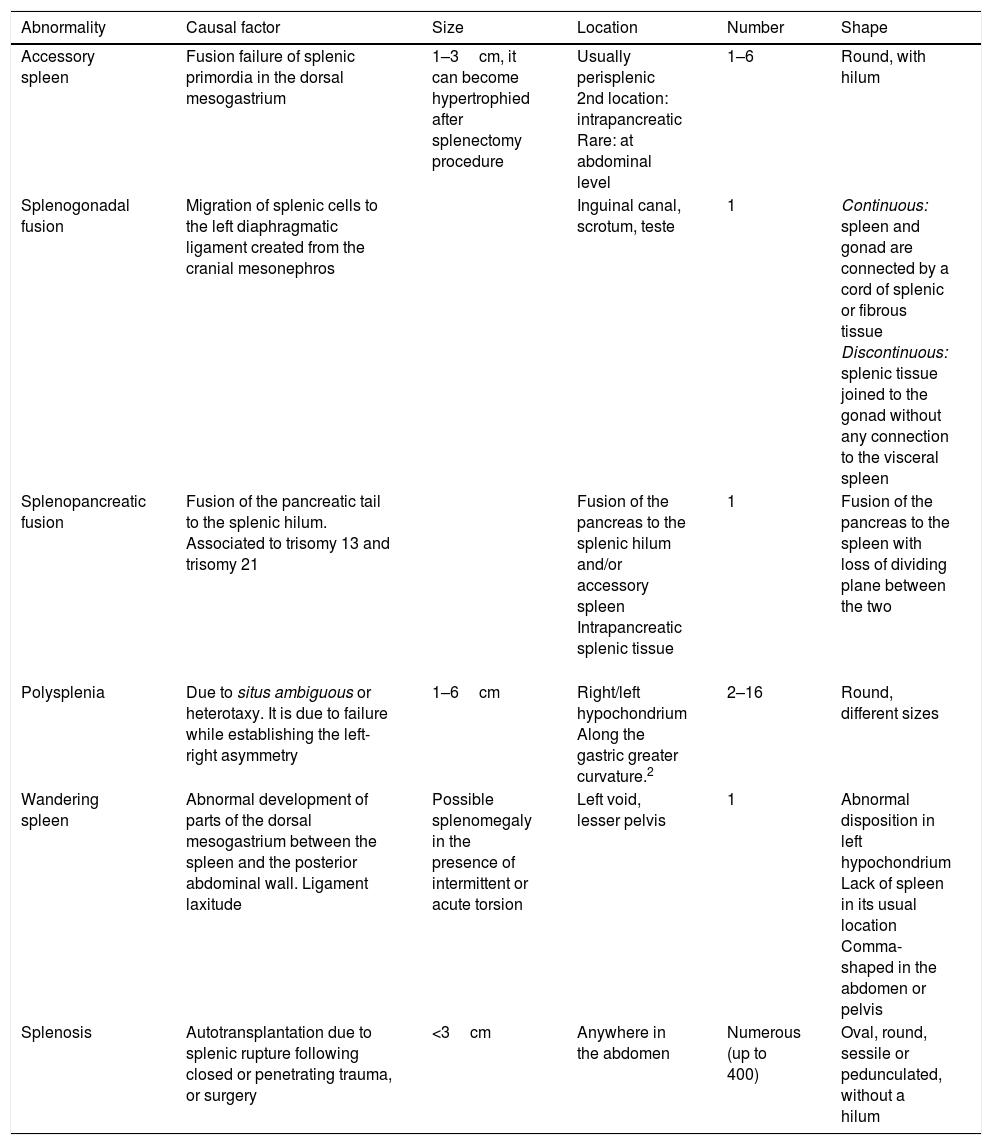

In order to understand congenital splenic abnormalities, it is a good idea to briefly review their embryonic development that starts during the fifth week of pregnancy. The spleen stems from the splanchnic mesoderm as a single or multiple outbreak of embryonic mesenchyme that later merges into the dorsal mesogastrium. The rotation of the stomach occurs during the sixth/seventh week of pregancy and it displaces the spleen from the middle line toward the left side of the abdominal cavity. At the beginning of the second month of pregnancy, the dorsal mesogastrium, that evolves into the greater omentum, separates giving rise to the peritoneal ligaments. During this process, the spleen keeps growing and remains joined to the dorsal mesogastrium through these ligaments that fix it to the primitive abdominal cavity and keep it in its usual position.1,2 The gastrosplenic ligaments, splenorenal and splenocolic, are usually present, except for the wandering spleen, while the splenoomental and splenophrenic ligaments are inconstant.1–3 During the fetal period, the spleen usually displays some sort of lobulated surface that will vanish during the embryonic development. Depending on the developmental stage at which abnormalities occur, accessory spleen, splanchnic heterotaxy (situs ambiguous), splenopancreatic or splenogonadal fusion, and wandering or ectopic spleen may occur1–5 (Table 1). On the contrary, splenosis is one acquired abnormality whose origin is at the autotransplantation of splenic tissue after trauma or surgery.

Categorization of splenic abnormalities based on their causal factor, size, location, number and shape.

| Abnormality | Causal factor | Size | Location | Number | Shape |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessory spleen | Fusion failure of splenic primordia in the dorsal mesogastrium | 1–3cm, it can become hypertrophied after splenectomy procedure | Usually perisplenic 2nd location: intrapancreatic Rare: at abdominal level | 1–6 | Round, with hilum |

| Splenogonadal fusion | Migration of splenic cells to the left diaphragmatic ligament created from the cranial mesonephros | Inguinal canal, scrotum, teste | 1 | Continuous: spleen and gonad are connected by a cord of splenic or fibrous tissue Discontinuous: splenic tissue joined to the gonad without any connection to the visceral spleen | |

| Splenopancreatic fusion | Fusion of the pancreatic tail to the splenic hilum. Associated to trisomy 13 and trisomy 21 | Fusion of the pancreas to the splenic hilum and/or accessory spleen Intrapancreatic splenic tissue | 1 | Fusion of the pancreas to the spleen with loss of dividing plane between the two | |

| Polysplenia | Due to situs ambiguous or heterotaxy. It is due to failure while establishing the left-right asymmetry | 1–6cm | Right/left hypochondrium Along the gastric greater curvature.2 | 2–16 | Round, different sizes |

| Wandering spleen | Abnormal development of parts of the dorsal mesogastrium between the spleen and the posterior abdominal wall. Ligament laxitude | Possible splenomegaly in the presence of intermittent or acute torsion | Left void, lesser pelvis | 1 | Abnormal disposition in left hypochondrium Lack of spleen in its usual location Comma-shaped in the abdomen or pelvis |

| Splenosis | Autotransplantation due to splenic rupture following closed or penetrating trauma, or surgery | <3cm | Anywhere in the abdomen | Numerous (up to 400) | Oval, round, sessile or pedunculated, without a hilum |

Accessory spleen (AS) is the result of the poor fusion between the splanchnic mesoderm outbreaks and the dorsal mesogastrium.1,2,6–8

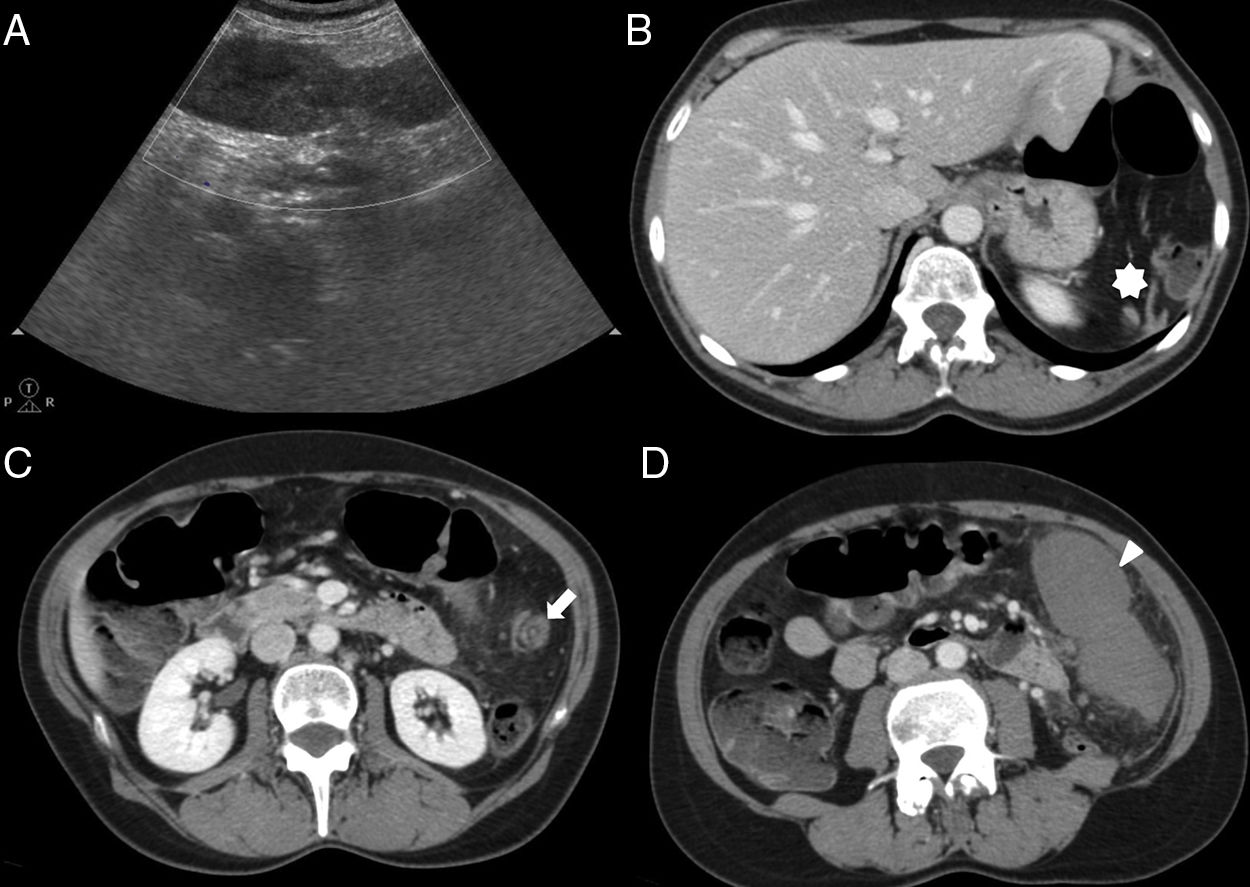

The incidence rate of AS is between 10% and 40% of all autopsies conducted, and between 45% and 65% of all splenectomized patients.6,7,9 In the imaging studies it is usually an incidental finding. It is usually solitary, although in 10% of the cases it is multiple – usually more than three and exceptionally more than six.1,2,6–8 From the morphological and functional points of view, the AS is identical to the main spleen. It is usually between 1.5cm and 3cm in diameter. They have hilum, blood flow usually coming from the splenic artery and draining into the splenic vein.8 They can become hypertrophied after the splenectomy of the main spleen1,2,7,9 (Fig. 1).

The accessory spleen can be found at any level in the abdomen, more usually in the splenic hilum (75–80% of the cases) followed by the pancreatic tail (17%) and, in decreasing order, it can be found in the greater omentum, gastrosplenic and splenocolic ligaments, mesenterium, gastric wall and small intestine, suprarenal location, ovary and scrotum.6,9

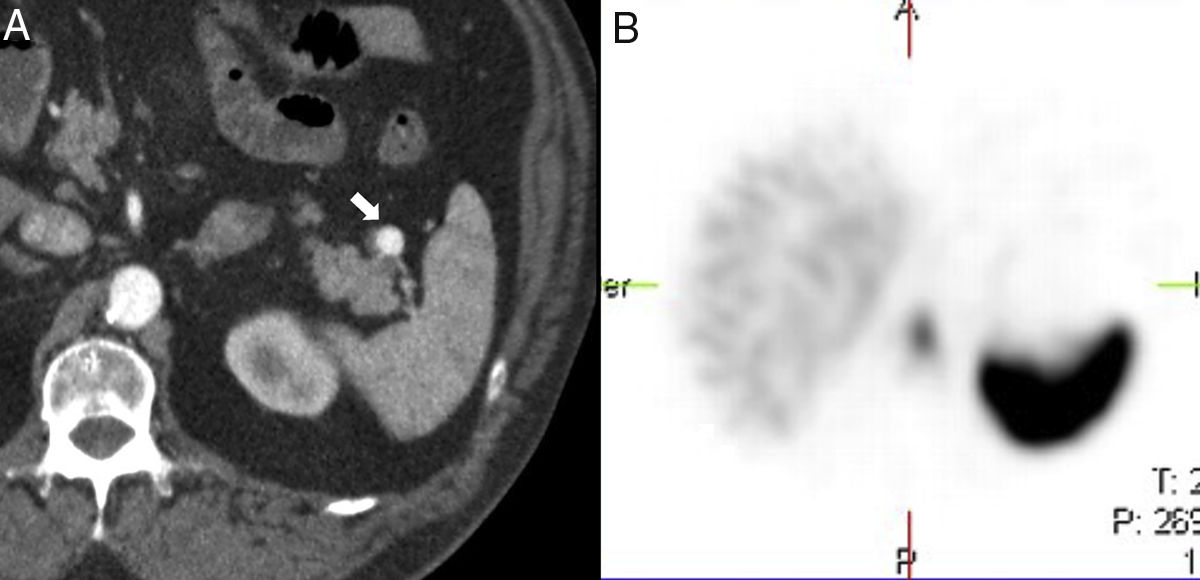

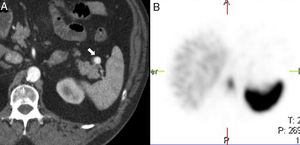

Although the diagnosis of perisplenic AS is usually very clear, an aneurysm in the splenic artery can be mixed up with an AS; however, in the aneurysm, the attentuation overlaps that of the adjacent arterial walls in all the phases (Fig. 2).

64-Year-old male with a positive fecal occult blood test. The CT scan with IV contrast in the arterial phase (A) shows one small hypervascular nodule anterior to the edge of the distal pancreatic tail. The lesion is hyperdense with respect to the spleen in the phase shown. The gammagraphy of denatured red blood cells marked with technetium-99m (B) shows the lack of isotope uptake by the nodule. It is consistent with an aneurysm of the splenic artery (note the similar attenuation of the aorta).

We should remember that when the AS is found in unusual locations it can be mixed up with adenopathies, hypervascular metastases, or primary tumors.1,2,6–16

The intrahepatic accessory spleen (IAS), whose detection has become more and more popular due to the improved resolution of radiological machines and the greater number of examinations conducted14 is especially relevant since, frequence-wise, it is the second most common location of the AS, which leads to differential diagnosis with neuroendocrine tumors and hypervascular metastases.

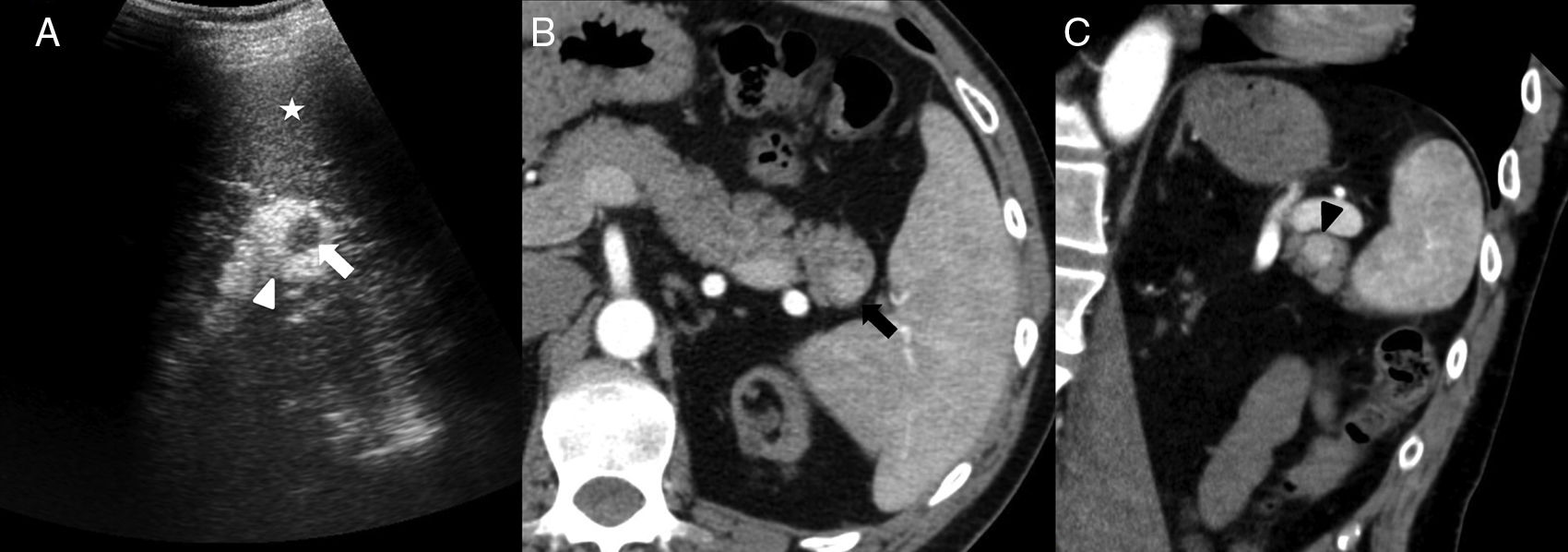

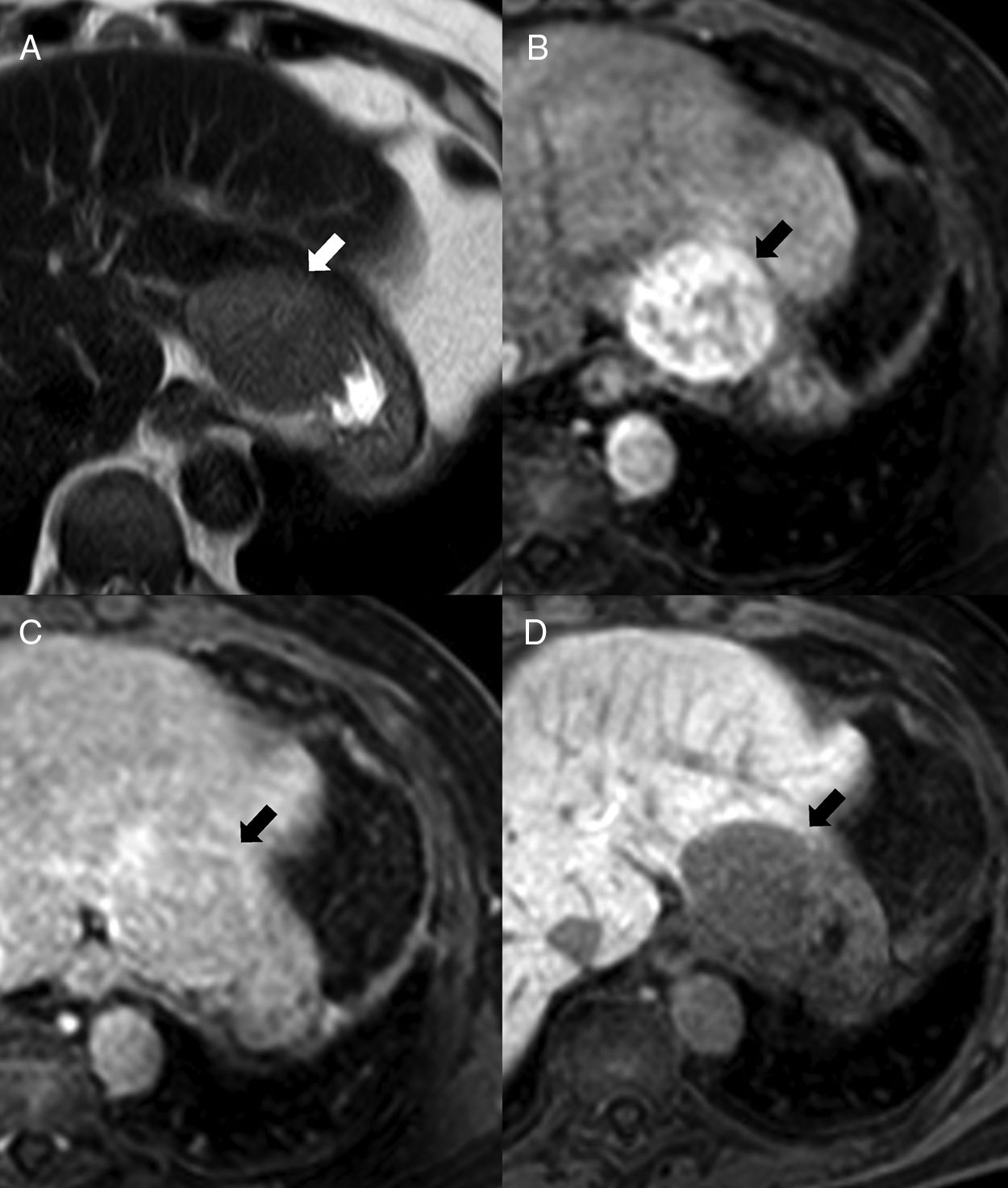

On the B-mode ultrasound imaging, the IAS looks like a round homogeneous nodule, isoechogenic to the spleen (Fig. 3) and capable of showing posterior reinforcement.6 On the Doppler ultrasound, the confirmation of a vascular hilum, that can be more easily identified on an ultrasound with contrast, makes its diagnosis easier.6

40-Year-old-male with chronic renal failure tested via ultrasound scan. The longitudinal ultrasound imaging (A) in left hypochondrium shows one hypoechogenic nodule (white arrow) in the hyperechogenic pancreatic tail (white arrowhead). Note how the nodule is isoechoic compared to the spleen (asterisk). The CT scan with IV contrast in the arterial phase (B) shows one hipervascular nodule (black arrow) on the edge of the pancreatic tail, isodense to the spleen, and consistent with an intrapancreatic accessory spleen. The oblique coronal reconstruction of CT scan (C) with contrast in the arterial phase shows one arciform enhancement pattern in the intrapancreatic accessory spleen (black arrowhead) similar to that of the spleen.

On the computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast, the attenuation of the IAS in all the phases is the same as that of the main spleen and higher than that of the pancreas (Fig. 3). This characteristic helps in the differential diagnosis of the pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor that is often isoattenuating or even washes out the contrast with respect to the pancreas during the venous phase of the study.6 However, in cases where splenic enhancement is delayed – such as in liver cirrhosis, the attenuation of the IAS can be lower than that of the pancreas during the arterial and pancreatographic phases.6

The splenic arciform pattern of contrast enhancement in the arterial phase (Fig. 3) can also be present in the IAS making it easy to differentiate it from the pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. However, the sometimes excessively small size of the lesion limits the identification of such a characteristic enhancement. It can also make it difficult to compare the attenuation association between the IAS and the main spleen.

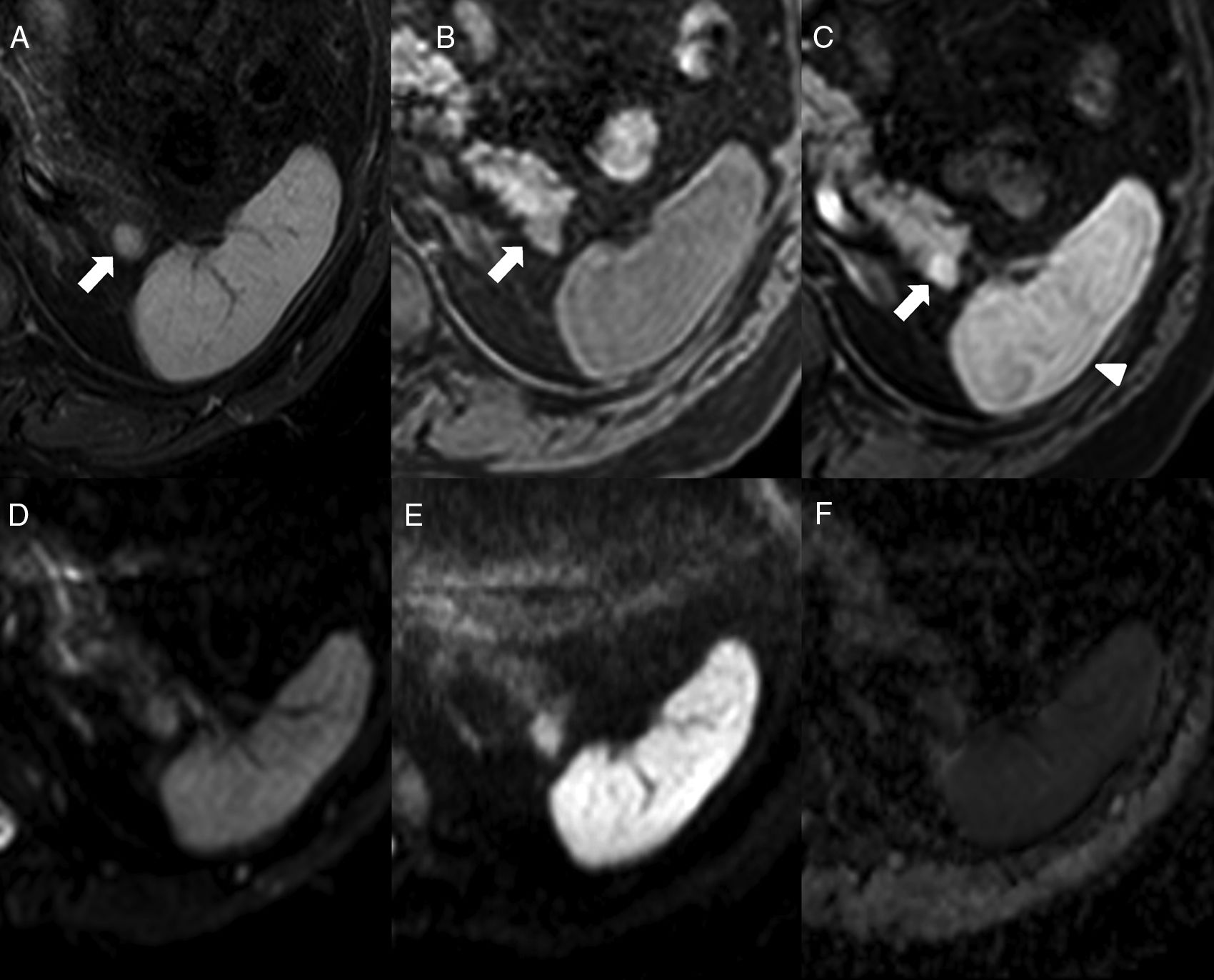

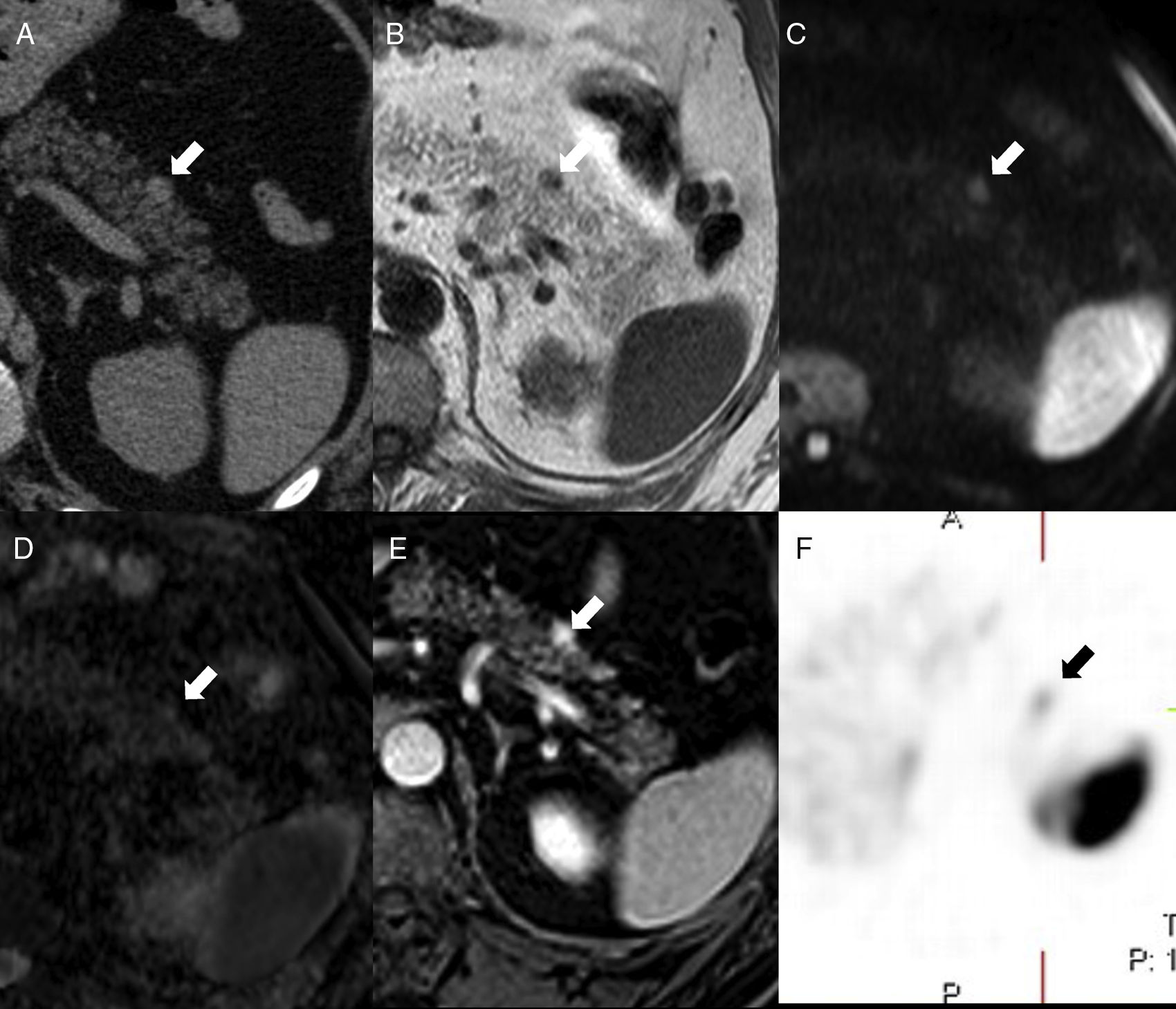

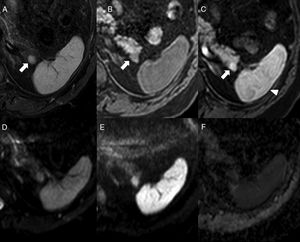

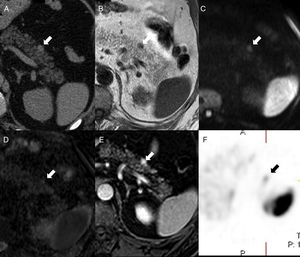

On the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the IAS looks hypointense compared to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma in T1 and hyperintense in T2, with a signal intensity that overlaps that of the main spleen in all MRI sequences6,9 (Fig. 4), which is key for its diagnosis. There can be a few exceptions to this though: occasionally, the IAS can be hyperintense with respect to the main spleen in FSE-T2, which is due to the fact that white pulp, that is responsible for the higher signal intensity in T2 due to the accumulation of water in the lymphoid follicles, holds in the IAS a ratio with the red pulp often higher than the one found in the main spleen. It has been reported that pseudopapillary solid tumors can show signal intensities in all b values both in diffusion and in the ADC map, being undistinguishable from those of the main spleen, although with a different behavior in dynamic studies.9 On the other hand, the pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor has ADC values that are significantly higher than those of the IAS, which is useful when conducting differential diagnoses between the two.17

64-Year-old-male with ankylosing spondylitis. The abdominal MRI shows one isointense nodule to the spleen in STIR (A) in the T1-weighted THRIVE sequence prior to the administration of contrast (B) and in the post-contrast study in the arterial phase (C) (note the arciform pattern enhancement of the spleen, arrowhead). In the diffusion sequences (D: b0, E: b1000 and F: ADC map), the intensity of the nodule is parallel to that of the spleen. It is consistent with one intrapancreatic accessory spleen.

We should remember that the signal intensity of the IAS compared to that of the main spleen overlaps in all MRI sequences including dynamic studies6,9 (Fig. 5).

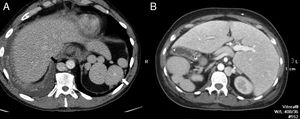

52-Year-old-male with a prior history of gouty arthritis. The CT scan without contrast (A) shows one small nodule (arrow) on the anterior side of the pancreatic tail – hyperdense compared to the pancreatic parenchyma and isodense compared to the spleen. On the MRI, the nodule is isointense to the spleen in T1 (B), diffusion (b1000, C) and ADC map (D). The phase-cycled balanced T1-THRIVE post-gadolinium sequence (E) shows the small lesion of the pancreatic tail with higher enhancement than the spleen. The in-111-pentetreotide (Octreoscan) (F) shows weak focal uptake where the lesion stands - consistent with one neuroendocrine tumor.

The IAS is usually found on the pancreatic tail, particularly at distal and dorsal level. There are very few chances that a pancreatic lesion in other locations will be an accessory spleen8 (Fig. 5).

On suspicion of IAS or splenosis, other imaging modalities can be useful such as the gammagraphy/single photon emission tomography of denatured red blood cells or sulfur colloid – both marked with Tc-99m.6,10,13 These imaging modalities use the activity of the reticuloendothelial system when it destroys the colloid or damaged red blood cells, somehow similar to how the spleen physiologically gets rid of damaged red blood cells. The limitation of this imaging modality is the poor definition shown by the uptake of planar images and the lower spatial resolution it has compared to radiological studies, which is why both imaging modalities are used together.6,10

On the contrary, imaging modalities based on somastostatin receptors or analogs are less reliable because these receptors can be found on the surface of both tumor cells and splenic lymphocytes.11,13,15,16

When non-invasive studies are not enough to reach diagnosis, one echo-endoscopy/CT scan-guided fine needle puncture aspiration procedure can be conducted. However, the size or location of the lesion can make this procedure not very easy to use.12,14

HeterotaxySplanchnic heterotaxy is the abnormal disposition of viscera and vascular structures unlike the normal disposition of the organs in the situs solitus, or the location, in specular image, of situs inversus.1 It is due to failure during the embryonic development while establishing the normal left-right asymmetry. Its etiology is unknown, although certain genetic mutations seem to be involed here.1,2

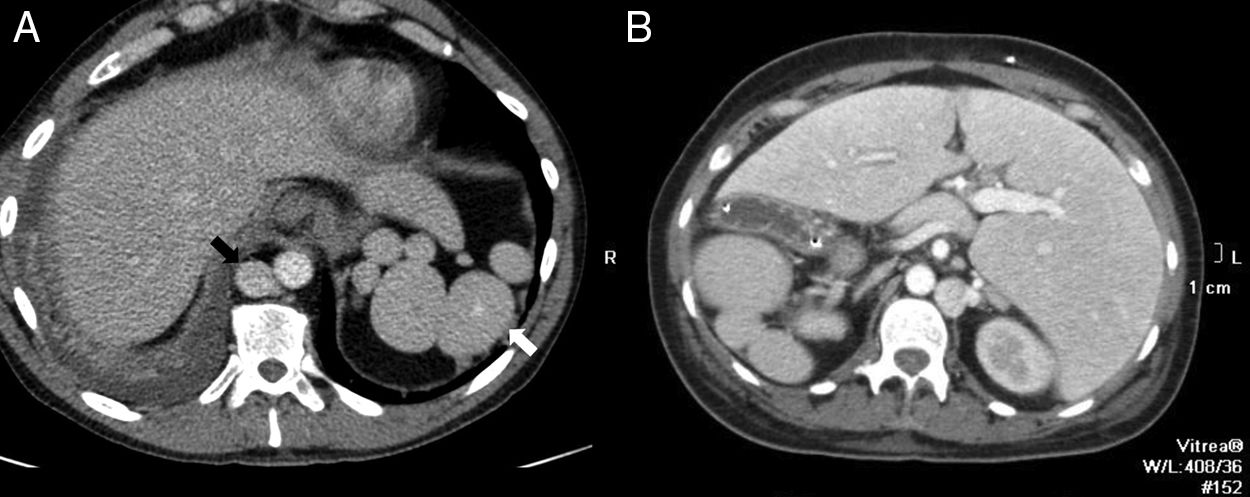

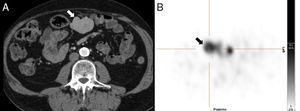

We should remember that heterotaxy associates two types of splenic abnormalities: asplenia and polysplenia. Asplenia, also known as Ivemark syndrome, shows no spleen on the imaging modalities, and polysplenia1 is a rare entity with multiple small spleens. Even up to 16 spleens can be counted here that are usually found in the gastric greater curvature.2 In the context of heterotaxy syndromes, polysplenia usually associates other congenital abnormalities such as agenesis or hypoplasia of the inferior vena cava, intestinal malrotation, or agenesis of the dorsal pancreas2 (Fig. 6).

51-Year-old-male with one pulmonary mass. The CT scan with IV contrast (A) shows findings of heteotaxy syndrome: polysplenia in left hypochondrium (white arrow) and lack of intrahepatic segment of the inferior vena cava replaced by the azygos vein (black arrow). Thirty-seven-year-old female with subocclusive clinical manifestations (B) with heterotaxy syndrome and situs inversus with specular image in the location of the polysplenia and hypertrophied azygos vein compared to case A.

Splenosis is one benign entity due to the autotransplantation of ectopic splenic tissue on intra and extraperitoneal vascularized structures following one splenic lesion due to closed trauma, injuries caused by a sharp instrument or firearm, or after conducting one splenectomy procedure7 (Fig. 7). The average time between the trauma and the appearance of abdominal splenosis is 10 years, ranging between 5 months and 32 years.7 Unlike the AS, the foci of splenosis do not have a hilum, show a somehow more distorted architecture, one less formed capsule, and their vascularization comes from local arteries that penetrate their capsule.2,18 Mostly, the splenic tissue harvesting is done by contiguity following the natural anatomical pathways, or the artificial anatomical pathways caused by the trauma.19 In a minority, dissemination is hematogeneous as it is the case of hepatic or cerebral splenosis – the latter being exceptionally rare.19

70-Year-old-male with a prior history of splenectomy 20 years ago. The ultrasound scan (not shown) shows one solid homogeneous mesenteric nodule of 4.7cm in size. The CT scan with contrast enhancement (A) conducted to characterize such nodule shows one centroabdominal mesenteric lesion with homogeneous enhancement. The gammagraphy of denatured red blood cells marked with technetium-99m (B) shows intense uptake of the lesion. After resection the diagnosis of splenosis was confirmed.

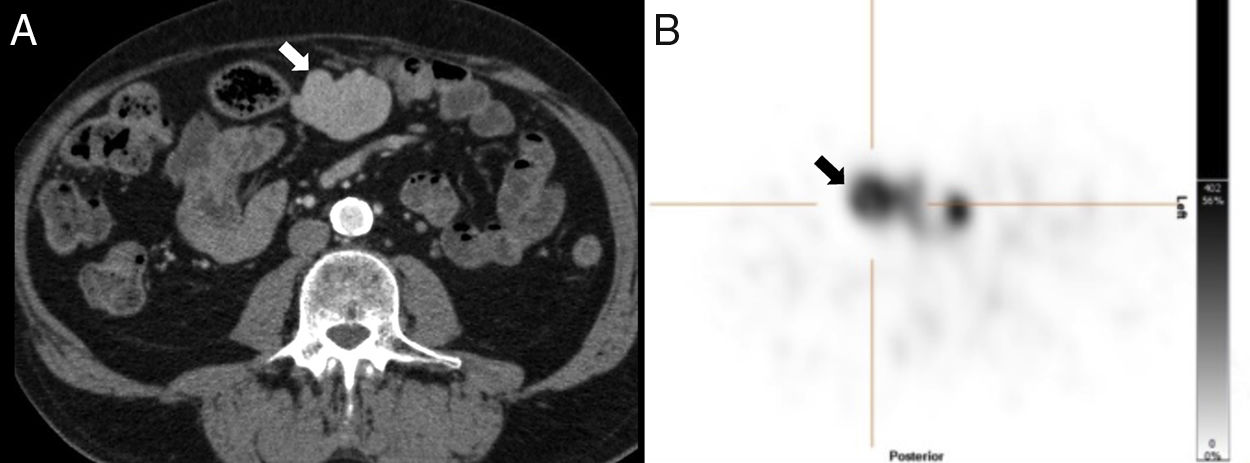

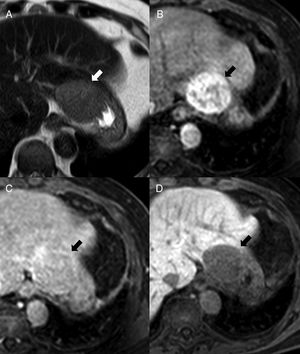

It is usually limited to the abdominal–pelvic cavity, and most implants lay on the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. Its most common location, in decreasing order, are: the serosal surface of the small intestine, greater omentum, parietal peritoneum, serosal surface of the colon, mesenterium, and diaphragm. Hepatic splenosis is rare and when it appears in cirrhotic livers it brings about the possibility of differential diagnosis with hepatocellular carcinoma due to its post-contrast enhancement characteristics7,20–22 (Fig. 8). Other uncommon locations are celiac axis, right paracolic gutter, pancreas, stomach, gallbladder, appendix, kidneys, ureters, lesser omentum, uterus, bladder, or uterine tubes. In cases of thoracoabdominal trauma with diaphragmatic rupture we can find thoracic splenosis, even damage to the pericardium and abdominal splenosis.7 Cutaneous splenosis is rare and it may be due to penetrating wounds.19 Only one (1) case has ever been reported of cerebral splenosis in the occipital lobe.19

55-Year-old-male with hepatic cirrhosis and splenectomy. The ultrasound scan conducted to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma given the patient́ condition (images not shown) shows one 5cm-mass in his left hepatic lobe. On the MRI the lesion, medial to the stomach, is hyperintense in T2 (A), heterogeneous hipervascular in the arterial phase after the administration of IV gadolinium (B), discreetly hypointense on the phase-cycled balanced (C) and partially surrounded by a thin capsule. The lesion appears hypointense in the hepatocellular phase after the administration of gadoxetic acid (D). The preoperative diagnostic suspicion was hepatocellular carcinoma, but the resection confirmed it was one intrahepatic splenosis.

Although abdominal splenosis is usually asymptomatic, it can also associate hemorrhages, pain due to infarction, or torsion and obstruction of the gastrointestinal or urinary tracts. Same as it happens with the AS, it can be mixed up with primary tumors or metastasic disease, lymphomas and endometriosis.20 The diagnosis of splenosis requires a high rate of suspicion, which is why it is important that the anamnesis shows any prior history of splenic lesion.7,20

We should remember that the set of diagnostic tests ran to detect splenosis is the same set of tests ran to detect the AS, and both entities can be distinguished following the patient's clinical history, location, number, size, shape, and pattern of vascularization.

Wandering spleenThe wandering or ectopic spleen is a rare variant resulting in the lack or anomalous laxitude of the ligaments supporting the spleen in its normal position. This abnormality can be acquired or congenital, and if congenital it associates a long vascular pedicle that can lead to torsion and infarction.4

When no acute complication is present, it is believed that up to 50% of the cases can go undiagnosed.2

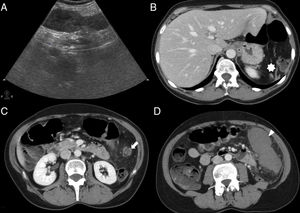

On both the ultrasound and the CT scan, findings include one spleen in ectopic location, or with an abnormal disposition in the left upper quadrant. It is often identified as a comma-shaped abdominal mass with no spleen in the left upper quadrant (Fig. 9).

55-Year-old-female with intense abdominal pain and fever. The longitudinal ultrasound slice through the left flank (A) shows one solid, discreetly heterogeneous structure without color Doppler signal inside. These CT scans with axial contrast (B, C and D) show the torsion of a wandering spleen. There is lack of spleen in the left hypochondrium (asterisk in B); the splenic vessels (not filled with contrast) make up a “whirlwind” in the left flank (arrowhead in C) and the non-enhancing spleen moves caudally (arrowhead in D). The splenectomy confirmed the torsion of the vascular pedicle of one wandering spleen associated to a hemorrhagic infarction of the organ.

We should remember that the torsion of the vascular pedicle can lead to both splenic infarction and venous thrombosis, or both. They appear as vascular “whirlpools” with ingurgitation, hypoenhancement of parenchyma or blood vessels, ascites or hemoperitoneum and striation of perisplenic fat.3–5

The management of symptomatic patients with splenic infarction is the splenectomy procedure, while the management of asymptomatic patients and those with torsion of the vascular pedicle without associated infarction is the splenopexy procedure.3–5

Splenovisceral fusionIt is predominant of males and it can be continuous (direct anatomical connection between the spleen and the gonad through the splenic cord), or discontinuous (no connection between the spleen and the gonad, but with ectopic splenic tissue encapsulated inside the gonad).1

In most cases, splenopancreatic fusion is associated to cases of trisomy of chromosomes 13 and 21. It is characterized by the fusion of the pancreatic tail and the splenic hilum and/or the accessory spleen with loss of dividing plane between these structures.1

ConclusionThe less common splenic abnormalities during development, and other abnormalities acquired such as splenosis, can pose diagnostic difficulties or be mixed up with other entities, thus leading to unnecessary therapeutic procedures. For diagnostic purposes we should remember here the embryonic development of the spleen. In the case of the accessory spleen it is useful to compare its behavior in the different imaging modalities to that of the main spleen, since they usually have a similar behavior. Also assess the possibility of splenosis when in the presence of a history of closed trauma or splenic laceration. Getting to know these entities is crucial to avoid making diagnostic mistakes.

Authors- 1.

Manager of the integrity of the study: BVS, MJP and DRV.

- 2.

Study idea: BVS, DRV and MJP.

- 3.

Study design: BVS, DRV and MJP.

- 4.

Data mining: BVS, MJP and DRV.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: BVS, MJP and DRV.

- 6.

Statistical analysis: N/A.

- 7.

Reference: BVS, MJP and DRV.

- 8.

Writing: DRV, BVS and MJP.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant remarks: BVS, MJP and DRV.

- 10.

Approval of final version: MJP, BVS and DRV.

The authors declare no conflicts of interests associated with this article whatsoever.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez Vargas D, Parada Blázquez MJ, Vargas Serrano B. Diagnóstico por imagen de anomalías en el número y localización del bazo. Radiología. 2019;61:26–34.