The relationship between traumatic brain injury (TBI) and parkinsonism has been established for a long time.1,2 However, in exceptionally rare cases there have been reports of parkinsonism secondary to traumatic lesions of the substantia nigra (SN).3 Case reports of parkinsonism due to SN lesions of vascular origin, either by lacunar stroke4–7 or by small mesencephalic haemorrhages,8 are better known, but also exceptional. Bhatt published a series of 3 patients who developed parkinsonism several months after a severe TBI with SN lesions. As characteristic data, there was a delay between the trauma and the onset of parkinsonism. The latter developed quickly and aggressively, with all patients responding to therapy with levodopa.3 A possible pathophysiological mechanism which was postulated to justify the delay in the onset of parkinsonism with respect to trauma, was iron deposition from the degradation products of the haemorrhagic lesion. This deposition would trigger the cascade of events typical of dopaminergic degeneration observed in idiopathic Parkinson's disease (IPD), thus explaining the response to dopaminergic therapy in these cases. When the SN is affected, the resulting parkinsonism is strictly unilateral, unless the injury is more extensive and affects other structures. We found very few references in the literature regarding the usefulness of computed tomography or positron emission tomography in this entity, and they mainly referred to cases with a vascular aetiology.9,10 Recently, a case of parkinsonism secondary to trauma with SN lesion was published in which the transcranial duplex study had not registered hyperechogenicity in the SN, unlike the characteristic pattern in IPD.11

We report a case of unilateral parkinsonism-dystonia secondary to traumatic injury of the SN and partially responsive to levodopa. We present the DaTSCAN study, which shows a notable decrease in radioisotope uptake in the striatum ipsilateral to the lesion.

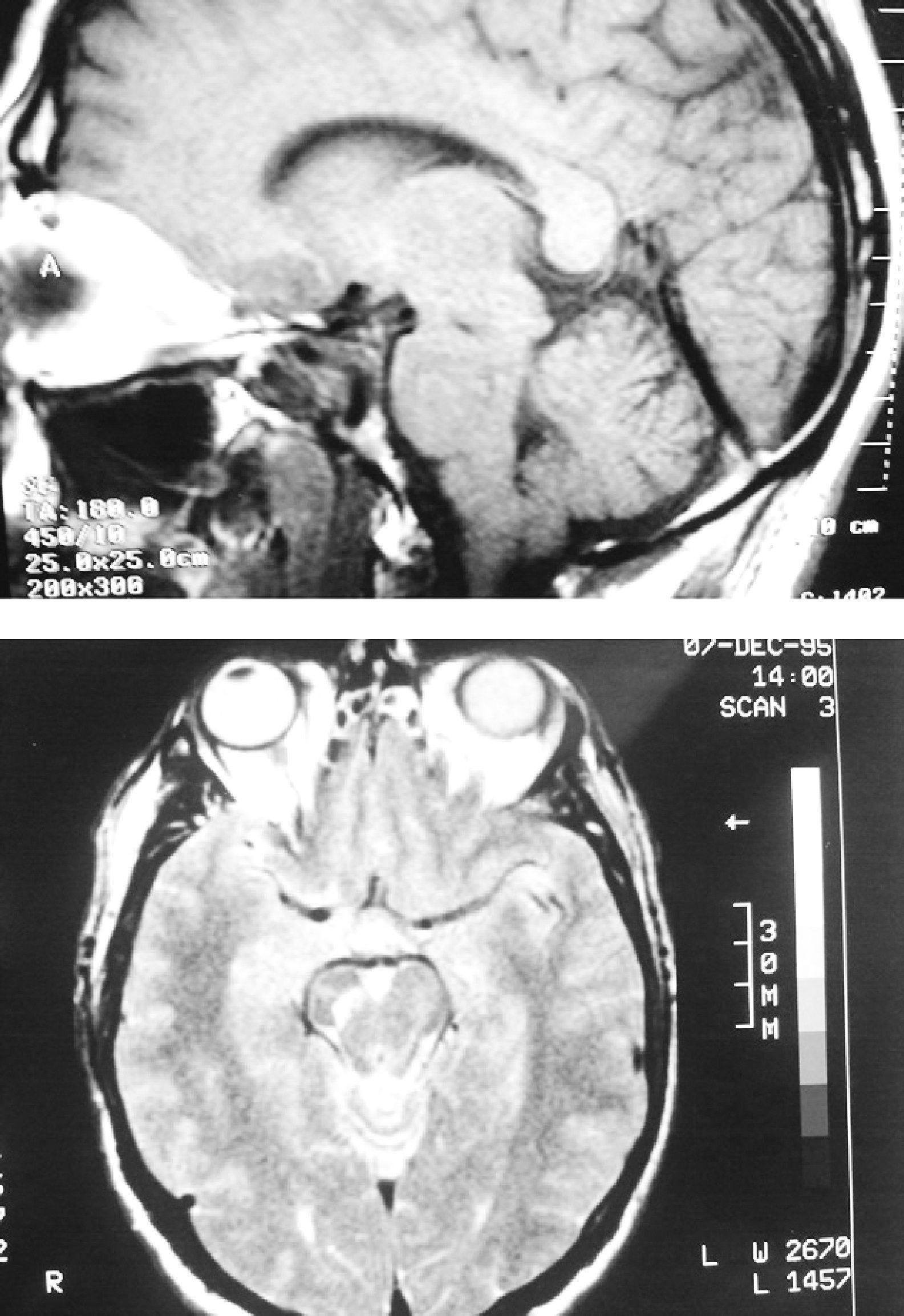

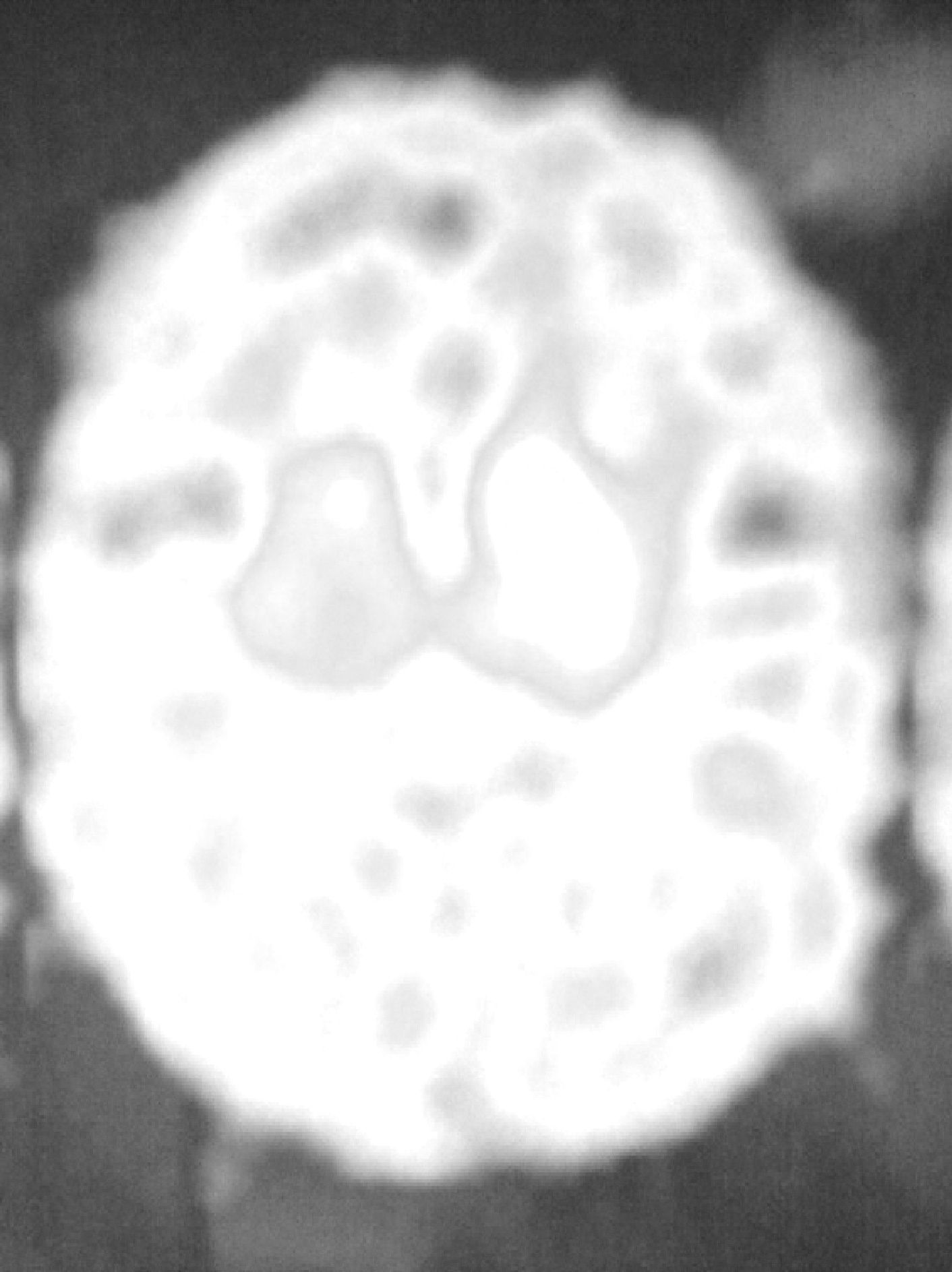

The patient was a 62-year-old male. At the age of 45 he suffered a TBI with loss of consciousness of 30–60min duration due to a fall from a second storey, with no apparent immediate neurological sequelae. One year later, he started to suffer uncontrolled and involuntary movements of the left limbs, which were more pronounced in the foot. The examination revealed hemidystonia, without any other significant signs. Two months later, in addition to hemidystonia, he suffered akinetic-rigid syndrome characterised by resting tremor, significant cogwheel rigidity and bradykinesia in the affected side of the body. These symptoms had a relatively rapid onset, with severe worsening of parkinsonism within a few weeks. A cranial MRI scan (Fig. 1) conducted at that time showed a right mesencephalic lesion at the level of the SN, with a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted sequences and a hypointense signal on T1-weighted sequences, and without signal alterations in neighbouring structures (adjacent red nucleus or cerebral peduncle) or at other brain levels. The radiologist reported the lesion as suggestive of residual gliosis in the context of the previous TBI. We conducted an analytical study which included thyroid hormones, Ca, P, Mg, ceruloplasmin, copper, blood smear for evaluation of acanthocytes and serology for syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus and Borrellia, with no relevant results. The patient was treated with levodopa/carbidopa at 100/25mg every 8h and displayed a partial response, but with a clear improvement over the pretreatment condition. Since then, his condition has remained stable (approximately 15 years have elapsed since the onset of symptoms), without exacerbation of symptoms or significant worsening or extension to the contralateral side of the body. He has not developed motor complications or dyskinesias associated with levodopa treatment. An attempt to withdraw levodopa was followed by clinical worsening, so it was reintroduced. Hemidystonia persists, but it is mild. At present, the patient continues treatment with levodopa-carbidopa at 300mg/day and extended-release ropinirole at 16mg/day. A DaTSCAN was performed recently (Fig. 2), and it showed a notable decrease in uptake in the right striatum and preservation of uptake in the left striatum.

It is well known that strategic lesions of the striatum or SN can cause symptomatic parkinsonism. The present case behaved like a strictly unilateral parkinsonism, developed months after a TBI. We should note that this parkinsonism occurred after a TBI which was not severe, since there were no immediate and persistent neurological sequelae, as has been previously reported.3 It started as hemidystonia prior to the development of parkinsonism. Dystonia has been associated with traumatic lesions of the basal ganglia, mostly thalamus and putamen, and also with a delay between trauma and the onset of symptoms.12 However, there were no lesions in those structures in our case. Recently, a case of hemidystonia due to SN lesion which responded to treatment with levodopa has been published.13 The cranial MRI scan revealed a lesion with gliotic characteristics at the level of the contralateral SN, with no evidence to justify its presence other than the TBI. Although a vascular lesion cannot be ruled out definitively, the fact is that there were no stroke symptoms at any time, no ischaemic lesions were observed at other levels and the patient presented no cardiovascular risk factors since the event occurred at an early age. In addition, vascular parkinsonism has been associated with an immediate onset after stroke and lack of response to levodopa. These requirements were not fulfilled in our case. Our patient responded to treatment (by this we mean a clear, initial improvement and subsequent stabilisation of symptoms), as described in the few cases reported.3 No motor fluctuations or dyskinesias associated with prolonged use of levodopa have been detected. We consider unlikely the possibility of IPD precipitated by the TBI, since parkinsonism has remained strictly unilateral after many years of evolution and the DaTSCAN findings are not those of IPD, with complete denervation of one side and preservation of the other. However, some authors have raised the possibility that TBI could facilitate the development of IPD a posteriori.3 DaTSCAN images verified striatal denervation by Wallerian degeneration following the SN lesion. We emphasise the uniqueness of this case and the novelty of providing a DaTSCAN study.

Please cite this article as: Pérez Errazquin F, Gomez Heredia MJ. Parkinsonismo-distonía unilateral sensible a levodopa por lesión traumática de la sustancia negra. Neurología. 2012;27:181–3.