Early TIPS is basically a new application of an old concept. This intervention used to be a useful rescue therapy when other interventions failed but has now become a primary intervention in patients with variceal bleeding and risk factors for poor prognosis. This technique has also been proven to control bleeding and has a definite survival advantage at 6 weeks and 1 year over standard therapy with vasoactive drugs and endoscopy, without increasing the rate of adverse events. In well-trained hands and with appropriate candidate selection, early TIPS is a safe, life-saving and evidenced-based procedure.

El TIPS precoz es una nueva aplicación de una herramienta conocida. Esta intervención ha pasado de ser únicamente una terapia de rescate útil cuando otras intervenciones han fallado a convertirse en la forma de tratamiento de los pacientes con sangrado variceal y criterios tempranos de mal pronóstico. Su uso ha demostrado, además del control adecuado de la hemorragia, una mejoría en la supervivencia a 6 semanas y un año en comparación al uso estándar de endoscopia y fármacos vasoactivos, sin condicionar un aumento del número de eventos adversos. En manos experimentadas y con una apropiada selección de los casos el TIPS precoz es un tratamiento seguro, que mejora la supervivencia y que está basado en la evidencia clínica.

Portal hypertension is the most feared complication of cirrhosis, due to its association with increased morbidity and mortality, as well as complications such as ascites, encephalopathy and variceal bleeding. Haemorrhage, which is correlated with high mortality, is the most serious of these complications.1–4

Major advances in the management of variceal bleeding in recent decades have gradually reduced 6-week, 6-month and 1-year rebleeding and mortality rates. In 2003, D’Amico and De Franchis performed a retrospective evaluation of 2 cohorts of cirrhotic patients admitted with variceal bleeding, showing that the mortality rate had fallen from a historic high of 40%1 to close to 20%.2 The main reasons for improved survival were: (1) general support and resuscitation measures; (2) prompt administration of vasoactive drugs; (3) extensive use of emergency endoscopy, and, albeit it less effective, (4) introduction of the rescue transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS).2

A similar recently published French study compared 2 historical cohorts, one from 2000 to 2001 and another more recent series from 2008 to 2009, finding a significant decline in 6-week mortality, from 24.6% to 10.9%. Among the reasons for this decrease were greater use of endoscopic ligation in the more recent cohort, a more restrictive transfusion strategy, widespread use of antibiotic prophylaxis and more frequent use of rescue TIPS. When the authors analysed this major difference in survival by subgroups, the most significant impact was observed in Child C patients, despite being the group with highest mortality.4

Nevertheless–and despite the improved prognosis achieved in recent years–bleeding episodes due to portal hypertension continue to be associated with significant mortality.

TIPS: what is it?TIPS consists of a shunt connecting a suprahepatic vein (usually the right or middle) to a portal branch (usually the right) in order to divert part of the portal blood flow and thus decompress the portal venous system.

Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents are currently recommended; expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (e-PTFE) is a non-thrombogenic material that prevents pseudointimal development, thereby reducing the possibility of stent dysfunction, a common problem when bare stents are used. Antibiotic prophylaxis against Gram-positive cocci and enterobacteria is recommended prior to TIPS placement in order to prevent infections, particularly endotypsitis, which is difficult to treat.

Because the procedure is carried out under deep sedation, the post-TIPS portal pressure gradient should be measured between the portal vein and inferior vena cava 24hours post-surgery, with the patient awake to avoid the effects of sedation and changes caused by respiratory oscillations accentuated during sedation. Follow-up is with Doppler ultrasound every 6 months to monitor patency and to ensure that the stent is working properly.5–7

One of the main problems associated with TIPS is the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy, which was higher with the bare stents formerly used. The general recommendation is to avoid very low portal-cava gradients, and to this end, stent dilatation diameter must be considered and candidates carefully selected. Patients aged over 65 years or with a history of encephalopathy have a higher risk of this condition. Although there is no specific portal-cava gradient that can accurately predict the risk, our group recommends gradients close to 10mmHg and less than 12mmHg, provided this is tolerated by the patient.

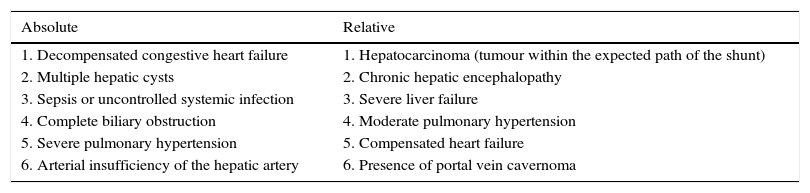

TIPS as rescue therapyTIPS is used as rescue therapy in variceal bleeding when standard management has failed, and is therefore known as salvage or rescue TIPS. Despite controlling bleeding in more than 95% of cases, this procedure has a high 30-day mortality of between 30% and 50%, essentially due to deterioration in liver function.8 For that reason, candidates for TIPS must be carefully selected, identifying patients with little likelihood of survival; the intervention is therefore not recommended in patients with a Child score greater than 13 points (as a measure of advanced liver disease), with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome or with active sepsis.9 Nevertheless, therapeutic failure of standard treatment is usually a dramatic situation that requires an individualised approach (Tables 1 and 2).

Absolute and relative contraindications to TIPS placement.

| Absolute | Relative |

|---|---|

| 1. Decompensated congestive heart failure | 1. Hepatocarcinoma (tumour within the expected path of the shunt) |

| 2. Multiple hepatic cysts | 2. Chronic hepatic encephalopathy |

| 3. Sepsis or uncontrolled systemic infection | 3. Severe liver failure |

| 4. Complete biliary obstruction | 4. Moderate pulmonary hypertension |

| 5. Severe pulmonary hypertension | 5. Compensated heart failure |

| 6. Arterial insufficiency of the hepatic artery | 6. Presence of portal vein cavernoma |

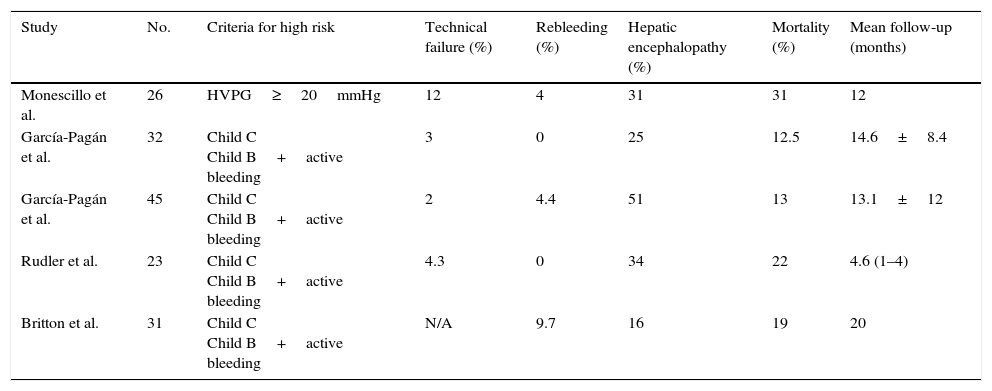

Characteristics of the clinical studies that validate the use of early TIPS.

| Study | No. | Criteria for high risk | Technical failure (%) | Rebleeding (%) | Hepatic encephalopathy (%) | Mortality (%) | Mean follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monescillo et al. | 26 | HVPG≥20mmHg | 12 | 4 | 31 | 31 | 12 |

| García-Pagán et al. | 32 | Child C Child B+active bleeding | 3 | 0 | 25 | 12.5 | 14.6±8.4 |

| García-Pagán et al. | 45 | Child C Child B+active bleeding | 2 | 4.4 | 51 | 13 | 13.1±12 |

| Rudler et al. | 23 | Child C Child B+active bleeding | 4.3 | 0 | 34 | 22 | 4.6 (1–4) |

| Britton et al. | 31 | Child C Child B+active bleeding | N/A | 9.7 | 16 | 19 | 20 |

As previously mentioned, despite advances in treatment and a decline in mortality rates, mortality continues to be high, approximately 10% at 6 weeks and 20% at 1 year. Initial treatment failure rates (10–15%) are also high. Much research into portal hypertensive bleeding today focuses on the identification of prognostic factors that can identify patients who, due to a high risk of standard treatment failure, would be candidates for a more aggressive approach early on (e.g. TIPS). Numerous studies have identified different parameters with significant capacity to predict standard treatment failure. Detailed analysis of these reveals that the most frequently recurring are: degree of deterioration of liver function, severity of portal hypertension (evaluated by the portal pressure gradient) and the presence of active bleeding when performing the diagnostic endoscopy. Other more recently described prognostic factors are the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score5 and total bilirubin level.10

Based on this concept, Monescillo et al.11 conducted a leading clinical study comparing the use of early TIPS (placed within the first 48–72hours after hospital admission) to the standard treatment used at that time (sclerotherapy and vasoactive drugs) in patients with liver cirrhosis and variceal bleeding in whom the portal pressure gradient was measured immediately following haemodynamic stabilisation. Patients included in the study were those with a gradient greater than or equal to 20mmHg, which was the criterion used to identify patients at high risk of therapeutic failure using pharmacological and endoscopic treatment only. This study confirmed the high risk in the selected population when medical treatment only was used, compared to a dramatic improvement in bleeding control and survival with early TIPS placement. This study was criticised for the difficulty experienced in most centres in measuring the portal pressure gradient to classify the patients into high and low risk, and because ligation was not the standard treatment used.

More recently, a new randomised, controlled, multicentre study conducted by García-Pagán et al.12 confirmed the results of the previous paper using a more pragmatic approach. In this study, high-risk patients were identified using simple clinical parameters available in any centre (Child C <14 points or Child B with active bleeding at the time of the initial endoscopy12,13). All patients were managed according to current clinical guidelines (ligation plus pharmacological treatment, restrictive blood transfusion strategy and prophylactic use of antibiotics) and the treatment group also underwent TIPS placement. All TIPS used were covered stents. This study again confirmed the importance of careful selection of patients for early TIPS. Thus, in the control group, therapeutic failure and mortality rates were very high compared to the early TIPS group. Early placement (within the first 72hours of admission, usually within the first 24hours) of a covered TIPS was shown to significantly reduce mortality at 6 weeks and 1 year of follow-up, mainly due to effective bleeding control and the prevention of therapeutic failure, thereby avoiding subsequent clinical deterioration.12

These results were validated in a second observational study conducted in the same centres that formed part of the initial study.13 In this study, all patients who were treated after the end of the randomised study and who had the same clinical characteristics that identified them as being at high risk of failure were selected. The progress of those who had received treatment by early TIPS as standard therapy was compared with those in whom pharmacological and endoscopic treatment was used. Again, patients treated with early TIPS had better bleeding control and lower mortality than patients who received pharmacological and endoscopic treatment.

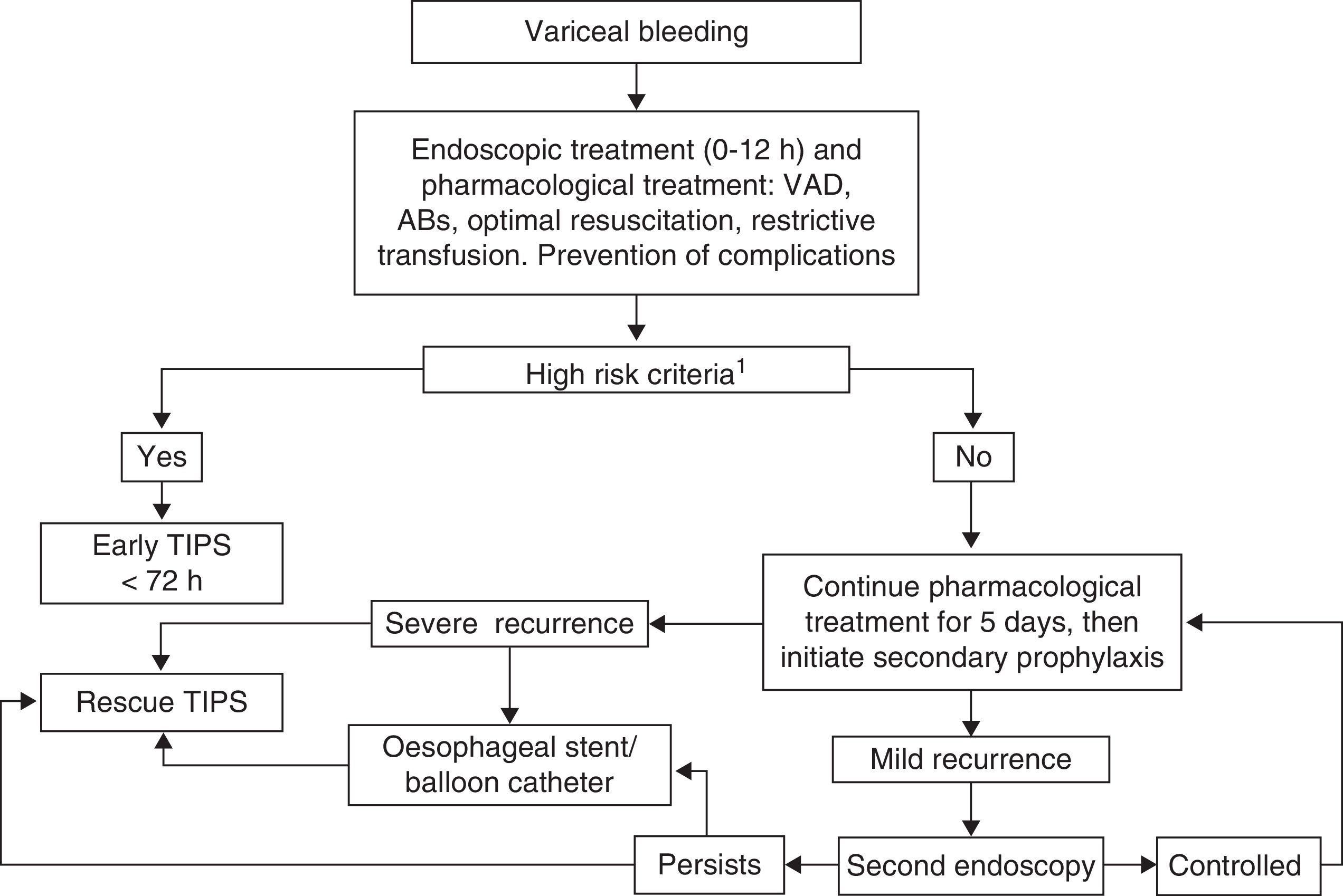

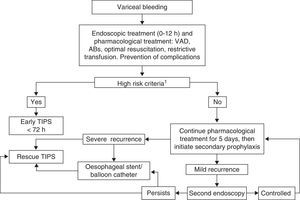

Based on this new information, it can be concluded that in patients with acute variceal bleeding and criteria for high risk of therapeutic failure with standard management, early TIPS placement in the first 72hours reduces the rate of recurrence and increases survival without increasing the rate of hepatic encephalopathy, with an incidence of serious adverse events that did not differ significantly from the control group (Fig. 1).

Flow diagram of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to oesophageal-gastric variceal bleeding. ABs: antibiotics (e.g. norfloxacin, ceftriaxone); VAD: vasoactive drugs (terlipressin, octreotide, somatostatin). aHepatic venous pressure gradient≥20mmHg, Child B with active bleeding on initial endoscopy, CHILD C up to 13 points.

Further studies are still needed to establish the current criteria used to select patients at high risk of therapeutic failure, or whether other criteria can be used to better classify this patient group. This task is complex and should be tackled with prospective, multicentre international studies that are already underway.

The beneficial effect of early TIPS as initial treatment in patients with high risk of bleeding recurrence is relevant, as are the possible secondary benefits–which remain to be shown in the coming years–in preventing other complications such as hepatorenal syndrome, intractable ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, among others.14

ConclusionEarly TIPS (placement in the first 72hours) is a treatment that reduces rebleeding, increases survival and presents few side effects (no more than in traditional treatment with drugs and endoscopy) in high-risk patients (Child C <14 points, Child B active bleeding). It should be implemented in experienced centres and is recommended by Baveno VI consensus guidelines on portal hypertension.15

FundingCIBERehd is financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-Blard E, Baiges A, Turon F, Hernández-Gea V, García-Pagán JC. Derivación portosistémica intrahepática transyugular precoz: cuándo, cómo y a quién. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:472–476.