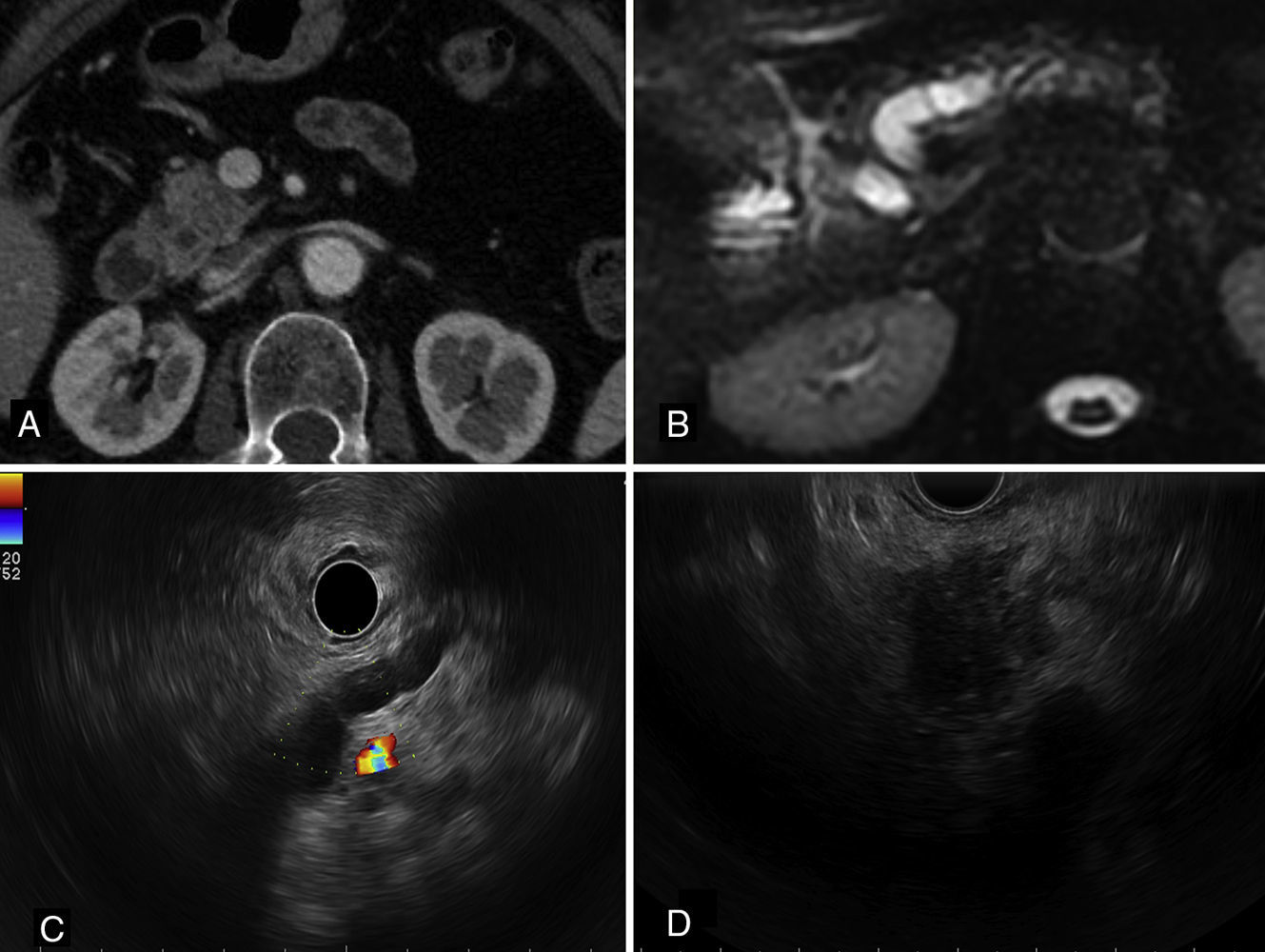

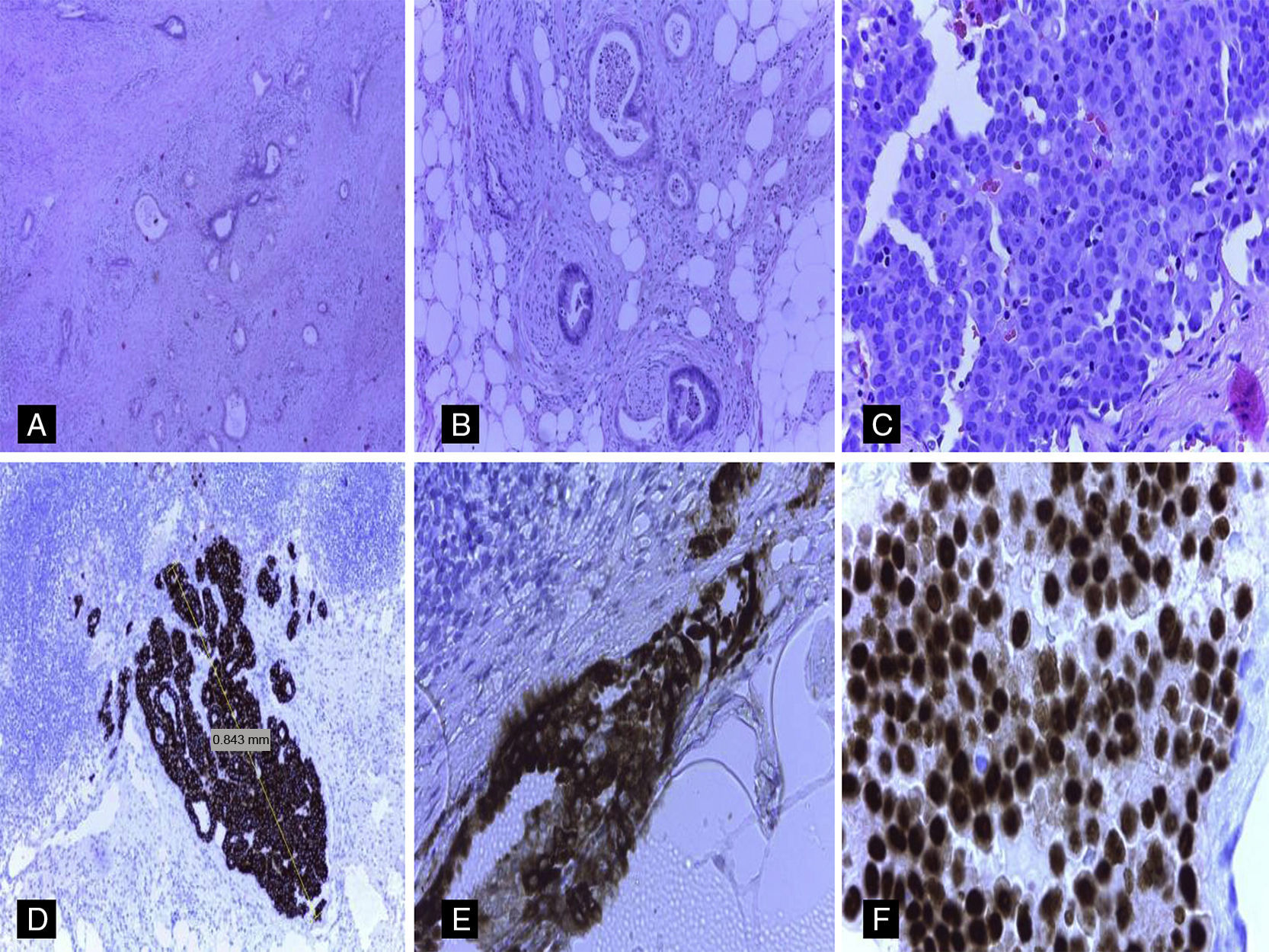

Lymph node staging in pancreatic carcinomas is of great prognostic and therapeutic importance.1 In the large majority of patients in whom peripancreatic lymph node metastases are detected, the primary origin of the tumor is the pancreas.1–6 Nevertheless, in patients with a history of extra-pancreatic neoplasms, it is essential to rule out the possibility of these pancreatic lymph node metastases originating from structures other than the pancreas.2–6 We describe an unusual case of micrometastasis in peripancreatic lymph nodes due to breast cancer in a patient who underwent resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient was a 72-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer in 2000, estrogen receptor (ER) positive and HER2 negative. The pathological stage was pT1b (8mm) N1 (1/20) M0. Radio- and chemotherapy were prescribed, along with hormone therapy with tamoxifen. Some years later, in 2013, she underwent surgery for a right lung tumor (mixed acinar/lepidic adenocarcinoma, cytokeratin [CK]-7++, thyroid transcription factor [TTF]-1+++), pathological stage pT2aN2 (3/14) M0. In November 2014, a follow-up study with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiography detected dilatation of the intra-and extrahepatic bile ducts with dilatation of the duct of Wirsung, with no clearly defined pancreatic lesion (Fig. 1A and B). A 20-mm lesion was found in the head of the pancreas on ultrasound endoscopy (Fig. 1C and D). Positron emission tomography (PET) was negative and CA19.9 values were elevated. Fine needle aspiration was positive for carcinoma. Cephalic duodenopancreatectomy was performed, and the macroscopic study showed a whitish, fibrous tumor in the head of the pancreas, 19mm at the largest diameter. Histopathological study confirmed the presence of a well-differentiated primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with infiltration of peripancreatic fat (pT3) and angiolymphatic and perineural invasion (Fig. 2A and B). Immunohistochemical (IHC) study of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma was positive for CA 19.9+++, CK7+++, CK19++, MUC1++, MUC5A++ and CK20+ (focal). Thirteen peripancreatic lymph nodes were isolated; 2 of them contained tumor nests measuring 0.84mm and 1.75mm at their largest diameter, corresponding to lymph node micrometastasis from a carcinoma with morphology different to that of the pancreatic neoplasm (Fig. 2C). The IHC study of the metastatic lymph nodes showed negative staining for CA 19.9, CDX2, TTF-1, GCDF15, CK20, HER2 and MUC5A and strongly positive staining for CK19, mammaglobin and ER (Fig. 2D–F). Staining for MUC1 and CK7 was positive (++). Based on the morphological findings and IHC, the final diagnosis was primary infiltrating pancreatic ductal carcinoma associated with peripancreatic lymph node micrometastases from a mammary carcinoma. An additional IHC study of the pancreatic tumor and the primary pulmonary neoplasm showed negative staining for ER and mammaglobin. Adjuvant treatment with gemcitabine and hormone therapy was prescribed.

(A) CT scan, showing minimal heterogeneity in the density of the head of the pancreas. (B) Magnetic resonance cholangiography showing dilatation of the bile and pancreatic duct. (C) Radial ultrasound endoscopy image from the gastric body, where dilatation and some beading of the duct of Wirsung can be observed in the body and tail of the pancreas. (D) Linear ultrasound endoscopy image from the duodenal bulb with presence of a heterogeneous hypoechoic nodule with poorly defined borders in the pancreatic head, measuring about 2cm, with no infiltration of the portal vein.

(A) Well-differentiated infiltrating pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], ×20). (B) Infiltration of the peripancreatic fat and perineural infiltration from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (H&E, ×40). (C) Metastases in peripancreatic lymph nodes from a carcinoma with morphology different to that of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma (H&E, ×40). (D) Strongly positive staining for CK19 in the lymph node micrometastasis (H&E, ×20). (E) Strongly positive mammaglobin (cytoplasmic staining) in lymph node micrometastasis from mammary carcinoma (H&E, ×40). (F) Strongly positive estrogen receptors (nuclear staining) in lymph node micrometastasis from mammary carcinoma.

Metastases in the pancreas account for fewer than 5% of all pancreatic neoplasms.2–6 Haematogenous and lymphatic spread, particularly from kidney and lung carcinomas, is the most common form of pancreatic involvement.1–6 Although the literature describes both the incidence and primary origin of pancreatic metastases,2–6 as far as we are aware, no studies have reported the incidence of metastases from extra-pancreatic carcinomas in peripancreatic lymph nodes dissected during the study of surgical specimens from cephalic pancreatectomies in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Furthermore, autopsy series have described single or multiple metastases in the pancreatic gland, but findings in the peripancreatic lymph nodes are not generally mentioned, unless the study involves a patient with pancreatic cancer.2–6 In the case described here, we found micrometastases from a mammary carcinoma in peripancreatic lymph nodes, which is an unusual finding. Considering this patient's history of lung and breast cancer and current diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the presence of peripancreatic lymph node metastases with a morphology different to that observed in the pancreatic tumor required a detailed IHC study, particularly to exclude the extra-pancreatic origin of these lymph node metastases. The IHC study of the metastatic lymph nodes in this case showed strongly positive staining for ER and mammaglobin, and negative staining for IHC markers that are often positive in lung or pancreatic cancer.7–9 These findings in the peripancreatic lymph nodes were consistent with the IHC profile of the primary breast tumor in this patient. Although some primary pancreatic or primary lung adenocarcinomas can occasionally show positive staining for mammaglobin or ER, it is rare for these neoplasms or their metastases to show positive for both markers.7–9 Moreover, in a patient with a history of estrogen-positive breast cancer in which distant metastases were detected, and where the metastatic tumor expressed mammaglobin and oestrogens, the most likely scenario is that the metastasis is of mammary origin, even though there are other primary tumors. It is well known that neither mammaglobin, oestrogens nor GCDF-15 are specific to mammary carcinoma, although these markers are the most widely used to rule out a mammary origin in metastases. Whilst new, theoretically somewhat more specific markers for breast carcinoma have been described (such as NY-BR-1 and GATA-3), they have some drawbacks, considering that NY-BR-1 can be expressed in cancer of the sweat glands, Müllerian tumors and even in pancreatic tumors. Similarly, GATA-3 expression is not limited to breast carcinoma.9

The detection of metastasis in peripancreatic lymph nodes from extra-pancreatic carcinomas provides the clinician with certain useful information. On the one hand, it can rule out possible additional metastases in other sites where metastases from breast cancer are frequently described (bone, liver and lung) and even a new primary breast tumor. It also suggests the best treatment strategy for these metastases that had hitherto remained undetected in clinical or radiological follow-up.

In conclusion, metastasis should always be considered in the study of any pancreatic mass or lesion in the peripancreatic lymph nodes in a patient with a history of other neoplasms. In this scenario, ICH results should be interpreted with caution and strictly correlated with morphological findings and clinical/radiological history.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Machado I, Caballero M, Martínez de Juan F, Marhuenda A, Martínez la Piedra C, Santos J, et al. Micrometástasis en ganglios peripancreáticos por carcinoma mamario en paciente con adenocarcinoma ductal pancreático. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:468–471.

![(A) Well-differentiated infiltrating pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], ×20). (B) Infiltration of the peripancreatic fat and perineural infiltration from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (H&E, ×40). (C) Metastases in peripancreatic lymph nodes from a carcinoma with morphology different to that of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma (H&E, ×40). (D) Strongly positive staining for CK19 in the lymph node micrometastasis (H&E, ×20). (E) Strongly positive mammaglobin (cytoplasmic staining) in lymph node micrometastasis from mammary carcinoma (H&E, ×40). (F) Strongly positive estrogen receptors (nuclear staining) in lymph node micrometastasis from mammary carcinoma. (A) Well-differentiated infiltrating pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], ×20). (B) Infiltration of the peripancreatic fat and perineural infiltration from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (H&E, ×40). (C) Metastases in peripancreatic lymph nodes from a carcinoma with morphology different to that of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma (H&E, ×40). (D) Strongly positive staining for CK19 in the lymph node micrometastasis (H&E, ×20). (E) Strongly positive mammaglobin (cytoplasmic staining) in lymph node micrometastasis from mammary carcinoma (H&E, ×40). (F) Strongly positive estrogen receptors (nuclear staining) in lymph node micrometastasis from mammary carcinoma.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/24443824/0000003900000007/v2_201704060210/S2444382416000456/v2_201704060210/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)