The term struma ovarii designates an uncommon class of ovarian tumors consisting only or mainly of thyroid tissue.1 Malignant transformation of struma ovarii occurs in approximately 5% of cases and may lead to the occurrence of metastases.2 On the other hand, differentiated thyroid cancer may metastasize to one or both ovaries, or occur concomitantly with struma ovarii.3 A case of concurrent malignant struma ovarii and papillary thyroid cancer is reported here.

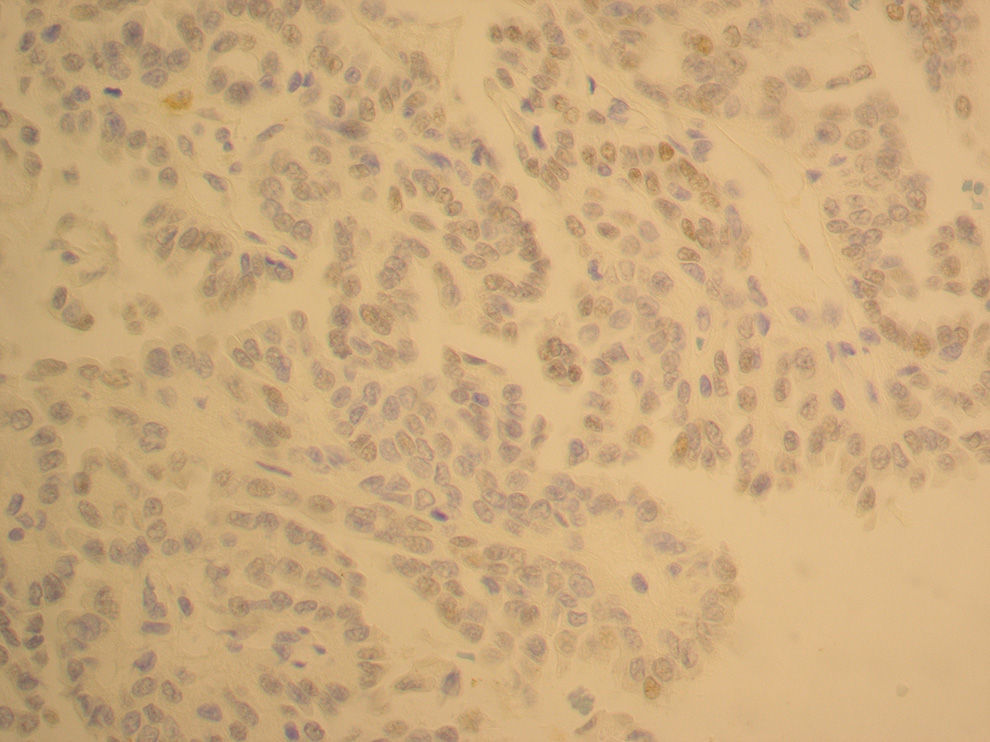

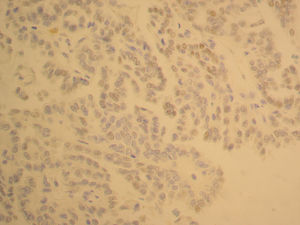

A 33-year-old female patient with no familial or personal history of thyroid disease was incidentally found to have a tumor in her left ovary during a cesarean section. Unilateral oophorectomy was therefore performed during the surgical procedure. The resected ovary weighed 194g and measured 9.5×7.5×3.5cm. A pathological examination confirmed the presence within a mature cystic teratoma of thyroid tissue representing 20–25% of the tumor. A capillary thyroid carcinoma 2.5cm in largest diameter was seen in the thyroid component (Fig. 1). There was no histological evidence of vascular, lymphatic, or extraovarian invasion. The results of thyroid function tests, performed before surgery, were normal.

The patient was referred to the endocrinology department of our hospital. Thyroid ultrasonography was performed, showing a 1.5cm hypoechoic nodule with ill-defined borders, located in the left thyroid lobe; fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the thyroid nodule was consistent with a benign follicular nodule. However, because of the ultrasonographic features of the thyroid lesion and to achieve adequate radioiodine (131I) uptake by the primary tumor, total thyroidectomy was performed. The surgical specimen weighed 14g, measured 7.1×2.5×2.2cm, and contained a poorly delimited nodule 1.4cm in largest diameter. The thyroid tumor turned out to be a classical papillary thyroid carcinoma with metastases to two lymph nodes and invading the perithyroidal soft tissue.

The administration of a dose of 100mCi of radioiodine (131I) was decided upon, and a subsequent whole body scan (WBS) revealed strong uptake in the thyroid bed, with no evidence of locoregional or distant pathological uptake. Suppressive therapy with levothyroxine was subsequently started. One year later, due to the persistence of a minimum residue in the neck area in a new WBS and detectable plasma thyroglobulin levels (8.6ng/mL) concurrent with elevated TSH levels (99.4IU/mL) and negative thyroglobulin antibodies (<60IU/mL), an additional dose of 100mCi of radioiodine (131I) was administered. The complete ablation of the thyroid remnant and the absence of abnormal extrathyroid uptake were verified during follow-up. Plasma thyroglobulin levels currently remain undetectable with stimulated plasma TSH levels. In addition, there is no evidence of tumor relapse six years after the initial diagnosis of malignant struma ovarii.

The coexistence of differentiated thyroid cancer and malignant struma ovarii in the same patient is an exceptional finding in clinical practice.4 Such synchronous occurrence raises the dilemma of whether the tumors are separate primary neoplasms coinciding in time, or whether one of them results from the distant metastatic dissemination of the other. Although this dilemma may be difficult to resolve, a number of phenotypic variables of the tumor and clinical data may be helpful in this regard.4

Phenotypic variables include the morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular characteristics of both neoplasms. In the reported case, both tumors showed morphological characteristics of a classical papillary thyroid cancer with a papillary and follicular pattern. The immunohistochemical pattern with HBME-1 (antibody against the microvillous surface of mesothelial cells), CK-19 (cytokeratin 19 of high molecular weight), and galectin-3 may also be of help in tumor characterization, but in our case the only difference shown was the absence of a positive result for galectin-3 in the thyroid neoplasm and a focal positive result for galectin-3 in the ovarian tumor. While the expression of some oncogenes such as BRAF, RAS, or RET/PTC has not been shown to be useful for characterizing synchronous primary tumors, the study of the clonal origin of these tumors by analyzing the differences in length of the polyglutamine tract of the human androgen receptor may be helpful.4

The following clinical variables have been used to establish the difference between synchronous primary tumors and differentiated metastatic disease: the dissemination pattern in WBS with radioiodine (131I) or positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), stimulated plasma thyroglobulin levels before radioablation, histological characteristics, and uni or bilateral ovarian tumor, as well as favorable or unfavorable prognosis during the course of the disease.4

Our patient had only left ovary involvement with a tumor of teratomatous characteristics; WBS after ablation therapy with radioiodine (131I) only showed uptake in the cervical bed, but no advanced metastatic disease; finally, thyroglobulin levels before thyroid ablation with radioiodine were not excessively high (16g/mL). After six years of clinical monitoring, the patient remains free of tumor recurrence. All of the foregoing suggests that this case had the clinical characteristics of two synchronous primary tumors.

Although the therapeutic management of malignant struma ovarii is controversial, it is advisable to perform neck ultrasonography and thyroid FNA if any thyroid nodule is detected. Total thyroidectomy is recommended if there is any suspicion of a malignant thyroid nodule.5

The synchronous presence of malignant struma ovarii and papillary thyroid cancer is usually associated with a favorable prognosis, unlike in the presence of metastatic disease having one or the other origin. The main barrier for making recommendations on the clinical management of these synchronous tumors is the rarity of their coexistence and the lack of sound scientific evidence.

Please cite this article as: Fernández Catalina P, Rego Iraeta A, Lorenzo Solar M, Sánchez Sobrino P. Estruma ovárico maligno y cáncer papilar de tiroides sincrónicos. Endocrinol Nutr. 2016;63:366–367.