Paragangliomas are neuroendocrine tumours derived from chromaffin cells of the extra-adrenal sympathetic nervous system and they represent an exceptional pathology within the mediastinum, comprising 1–2% of all paragangliomas and less than 0.3% of all mediastinal tumours. The patients' symptoms will depend on functionality and on compressive symptoms because of its large size, although in half of patients it presents as an incidental finding on imaging tests.1,2

We present the case study of a functional mediastinal paraganglioma in the middle mediastinum, for which multidisciplinary management was carried out.

The patient was a 55-year-old woman with a personal history of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidaemia, who was examined at a private centre for syncope, palpitations and dyspnoea.

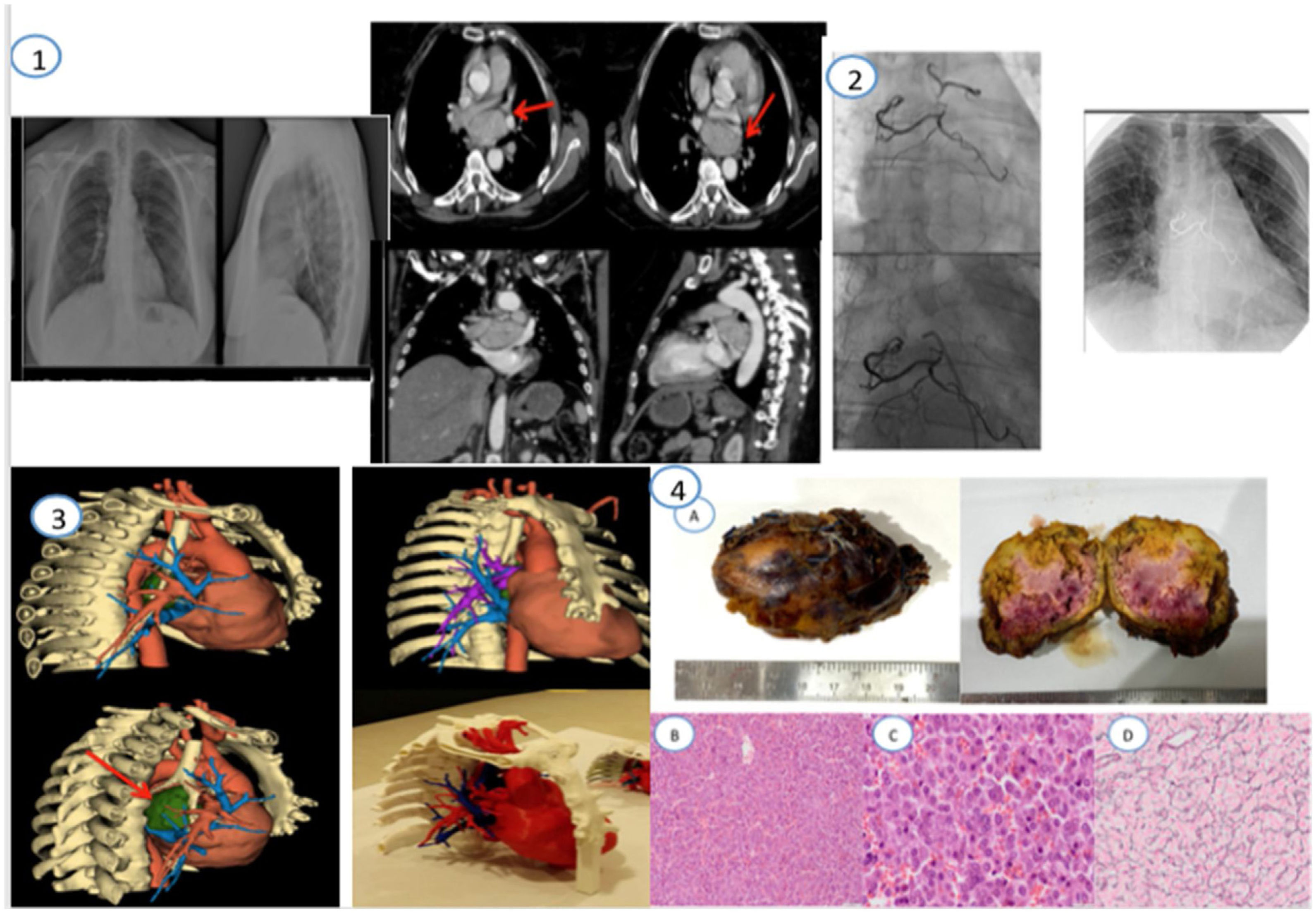

The initial study included laboratory tests, chest X-ray, CT scan of the chest and abdomen, and echocardiogram. Following laboratory test findings of catecholamines in 24-h urine: normetanephrine 3,025 μg/24h (88–444), metanephrine 85 μg/24h (52–341), elevated chromogranin A (no numerical value available) and imaging (mediastinal large tumour measuring 6×7cm in the middle mediastinum, near the carina, nourished by coronary and bronchial irrigation), mediastinal paraganglioma was diagnosed. At the adrenal glands, no nodules or masses were observed that would suggest a multiple location of the tumour.

The patient was referred to our centre and seen by Endocrinology, who adjusted the alpha-blocker treatment with doxazosin prior to embolisation by Vascular Interventional Radiology (VIR) and subsequent resection by Cardiovascular Surgery (CVS).

A second chest CT scan was performed, which studied the relationship of the lesion to adjacent vascular structures, revealing close contact with the pulmonary veins, left pulmonary artery and left atrium, with irrigation of small arteries from the right coronary artery and left bronchial artery.

The arteriogram performed by VIR showed the tumour irrigation and nutrient vessels that came from multiple arterial branches dependent on the right coronary artery and the left bronchial artery. In the first instance, Onyx 18® (a non-adhesive liquid embolic agent comprising an ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, to which tantalum powder was added for visualisation under fluoroscopy) was used for embolisation of the nutrient branches of the upper pole of the mass from the aorta (bronchial branches), with approach via the right femoral artery. Then, the atrial branches that perfused the lower pole of the tumour (coronary branches) were embolised with Onyx 18® through cardiac catheterisation, with approach via the radial artery. There were no complications during the procedure.

Subsequently (24h later), surgical excision was performed, planned using a 3D model. A median sternotomy and ligation of multiple arterial and venous tributaries from the descending aorta and coronary arteries were performed, as well as dissection of the area adhered to the left coronary artery and the left atrial roof, with complete resection of the tumour achieved without the need for extracorporeal circulation. The patient had a favourable course after surgery, with no signs of infection or tumour remnants.

Pathology results described an orange specimen with violet-coloured areas and a smooth surface, positive for chromogranin, enolase, synaptophysin, CD56, S100 and vimentin, consistent with a WHO grade I paraganglioma (Fig. 1).

(1) PA and lateral chest X-ray. Chest angio-CT with IV contrast at diagnosis. A large tumour is observed in the middle mediastinum, close to the carina, which is nourished with coronary and bronchial irrigation. (2) Outcome after Onyx embolisation of the coronary branches and bronchial branches by VIR. (3) Model for surgical planning with 3D reconstruction. The tumour is represented in green. (4) Pathological study. Macroscopic specimen (A). Haematoxylin and eosin 10×: a small increase where a neoplasm with a trabecular/nesting pattern is observed that is vascularised and with extravasation of red blood cells. The cells are surrounded by extensive, eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm with no overt atypia. (B) Haematoxylin and eosin 40×: with greater magnification, we observed extensive, granular and eosinophilic cytoplasm cells with a nucleus with salt-and-pepper chromatin (C) Reticulin: with the reticulin histochemical technique, a characteristic trait of this entity is observed with the reticulin fibres arranged in the form of baskets or trabeculae in which the cells of the paraganglioma are arranged in a form known as Zellballen (D).

After the procedure, a genetic study of familial paraganglioma with SDHB mutation was conducted, and the result was negative. The patient has now been followed up for three years with normal metanephrines.

Paragangliomas are highly vascularised neuroendocrine tumours arising from cells derived from the neural crest of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.1 They can appear in the abdomen, pelvis, thorax, head and neck and are classified as sympathetic or parasympathetic, depending on their origin.2 Their prevalence is higher in middle-aged patients (40 years old), with no predilection between genders.1–3

A mediastinal location is extremely rare (approx. 2% of cases) and they are mainly located in the middle and posterior mediastinum, with few cases in the literature similar to ours.4–10

Most mediastinal paragangliomas (50–80%) are non-functional. However, some paragangliomas may secrete catecholamines (as in our case) and may be multicentric if associated with familial syndromes (multiple endocrine neoplasia [MEN], von Recklinghausen's disease, von Hippel–Lindau disease, Sturge–Weber syndrome).

Currently, a genetic cause in the germline can be identified in approximately 40% of paragangliomas.3

At least 10% of sympathetic paragangliomas are malignant, although rates of malignancy differ according to hereditary history1 and may cause metastases to the ganglionic chains, lung, spleen and bone.11

The clinical presentation in functional tumours is usually arterial hypertension, tachycardia, headache and syncope, and in non-functional paragangliomas the symptoms depend on the compression of adjacent structures, leading to chest pain, dysphagia, dyspnoea or dysphonia.1–3

Diagnosis is established by clinical, laboratory and imaging tests, and it is an incidental finding in approximately half of patients.2

On CT it presents as a hypervascular lesion, with areas of necrosis or haemorrhage being visible. In certain cases, the study is completed with nuclear medicine tests, with different options available such as I-123 or I-131 mIBG scintigraphy; the latter has a sensitivity of 88%, specificity >95% (multiple paragangliomas), or PET-CT with 18F-DOPA or 68Ga-DOTATOC (metastasis).1–3

In the event of clinical suspicion of mediastinal paraganglioma, it is very important to avoid biopsy because of the high risk of bleeding.

Paragangliomas are treated surgically, with pre-operative pharmacological blockade (alpha- and beta-adrenergic).5–7 In addition, pre-operative angiography and embolisation should be performed if there is a high risk of bleeding, as is the case in large tumours or tumours in a location that make exeresis difficult (mediastinal, cervical and carotid body paragangliomas), as described in published articles where this procedure was necessary. Embolisation is preferably performed with Onyx as it is a safe embolic agent.8,12

The definitive diagnosis is established by the pathology of the surgical specimen, where Zellballen (S100-positive) characteristic of paragangliomas are observed.1–3

During follow-up, in addition to imaging tests, all patients with paraganglioma are recommended to undergo a genetic study as well as metanephrine analysis every year to detect local or metastatic recurrences, as well as the appearance of new tumours. This should be performed for at least 10 consecutive years in all patients who undergo surgery, and those at high risk (patients who are young, who have positive genetics or a large tumour) should be followed up annually for life.

Mediastinal paraganglioma is therefore a rare tumour, which will require management by a multidisciplinary team to achieve optimal treatment and avoid associated complications.