Knowledge of the microbiology of surgical infections after abdominal surgery can be of use when prescribing effective empirical antibiotic treatments.

MethodAnalysis of surgical infections after abdominal surgery in patients enrolled in the Prevalence of Infections in Spanish Hospitals (EPINE) corresponding to the years 1999–2006.

ResultsDuring the period of the study, 2280 patients who were subjected to upper or lower abdominal tract surgery were diagnosed with an infection at the surgical site (SSI). Eight hundred and eighty-three patients (37%) had an operation of the upper abdominal tract (gastric, hepatobiliary, and pancreatic surgery) and 1447 patients (63%) had lower abdominal tract surgery (appendectomy and colon surgery). A total of 2617 bacterial species were isolated in the 2280 patients included in the analysis. The most frequent microorganisms isolated were, Escherichia coli (28%), Enterococcus spp. (15%), Streptococcus spp. (8%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7%), and Staphylococcus aureus (5%, resistant to methicillin 2%). In the surgical infections after upper abdominal tract procedures, there were a higher proportion of isolations of staphylococci, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Acinetobacter spp. and Candida albicans and less E. coli, Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium spp.

ConclusionThe microbiology of SSI produced after upper abdominal tract surgery did not show any significant differences compared to those of the lower tract. However, more cases of SSI were detected due to staphylococci, K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Acinetobacter spp. and C. albicans and less caused by E. coli, B. fragilis and Clostridium spp.

El conocimiento de la microbiología de las infecciones quirúrgicas tras cirugía abdominal puede contribuir a la prescripción de regímenes de tratamiento antibiótico empírico eficaces.

MétodoAnálisis de las infecciones quirúrgicas tras cirugía abdominal en pacientes incluidos en el estudio de prevalencia de infecciones en hospitales españoles (EPINE) correspondiente a los años 1999-2006.

ResultadosDurante el período de tiempo considerado en el estudio se diagnosticaron 2.280 pacientes con infección del sitio quirúrgico (ISQ) que había sido sometidos a cirugía del tracto digestivo superior o inferior. Ochocientos treinta y tres pacientes (37%) habían sido intervenidos del tracto abdominal superior (cirugía gástrica, hepatobiliar y pancreática) y 1.447 pacientes (63%) del inferior (apendicectomía y cirugía de colon). Se aislaron 2.617 especies bacterianas en los 2280 pacientes incluidos en el análisis. Los microorganismos aislados con más frecuencia fueron Escherichia coli (28%), Enterococcus spp. (15%), Streptococcus spp. (8%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7%), y Staphylococcus aureus (5%, resistentes a meticilina 2%). En las infecciones quirúrgicas tras procedimientos digestivos altos hubo una mayor proporción de aislamientos de estafilococos, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Acinetobacter spp. y Candida albicans y menor de Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis y Clostridium spp.

ConclusiónLa microbiología de las ISQ producidas tras intervenciones del tracto digestivo superior no mostró diferencias acusadas en relación a las del tracto inferior. No obstante, se detectaron más casos de ISQ debidos a estafilococos, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Acinetobacter spp. y Candida albicans y menos causados por Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis y Clostridium spp.

Despite advances in antisepsis and operating technique, surgical site infections (SSI) are a considerable problem for patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery.1–3 These infections can affect all areas, from the skin and subcutaneous tissue to deeper structures of the abdominal cavity.1,4 Their appearance usually leads to increased hospital stay and may jeopardise the patient's life.1,4,5 Most studies have found some incidence of SSI after abdominal surgery, with values ranging between 3% and 20%.1,6–8 Certain circumstances, such as patient comorbidity, degree of contamination of the surgical field and duration of the intervention may modify the chance of acquiring SSI.7,9,10 Other factors related to these infections include age, nutritional status, obesity and preoperative preparation.1,11

Factors such as hospital stay and prior antibiotic therapy may influence the microbiology of the SSI observed.8,12,13 Due to the increased frequency of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, in these complications both the antibiotic prophylaxis administered and empirical therapy used may not be appropriate in some cases.14

The aim of this study was to investigate the microbiology of surgical infections occurring after gastrointestinal tract surgery in a representative sample of Spanish hospitals.

MethodThe information was obtained from the database of the prevalence studies of nosocomial infections in Spanish hospitals (EPINE). This is an annual survey conducted in a large sample of Spanish hospitals which gathers clinical information about both patients and their infections.15

This study selected patients included in the EPINE study who had developed surgical infection after abdominal surgery during the period 1999–2006. To determine the aetiology of the infections depending on their location (incision, organ, or space), the infections occurring in patients undergoing abdominal cavity interventions performed in general surgery departments were considered (this included both interventions with a low risk of infection, such as groin hernia surgery or splenectomy, and large bowel procedures). A comparison was then made between patients with upper digestive tract surgery (gastric, pancreatic and hepatobiliary surgery) and those with lower digestive tract surgery (appendectomy and colorectal surgery). This section did not include infections detected after other surgical procedures, such as those of the small intestine, as the flora that causes infections in this location may vary depending on their proximal or distal location.

The diagnosis of infection and categorisation of surgical procedures were performed according to the Centers for Disease Control criteria.16 Operating risk was assessed according to ASA.17 Data from the EPINE study were taken from patient medical records, nursing records, and directly from the patient and attending professionals, when necessary. The results of microbiological studies and other complementary tests were especially examined.

The main variables collected from patients who had an infection in the review were age, sex, infection location, microbiological aetiology, and a set of intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors.1,4,8,15

Categorical variables were expressed as percentages; continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation. To evaluate the differences in means in the univariate analysis, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used. To compare categorical variables, the Fisher's exact test was used if the sample was less than 5, and the Chi-square test if not. Statistical significance was a P value with a tail less than .05.

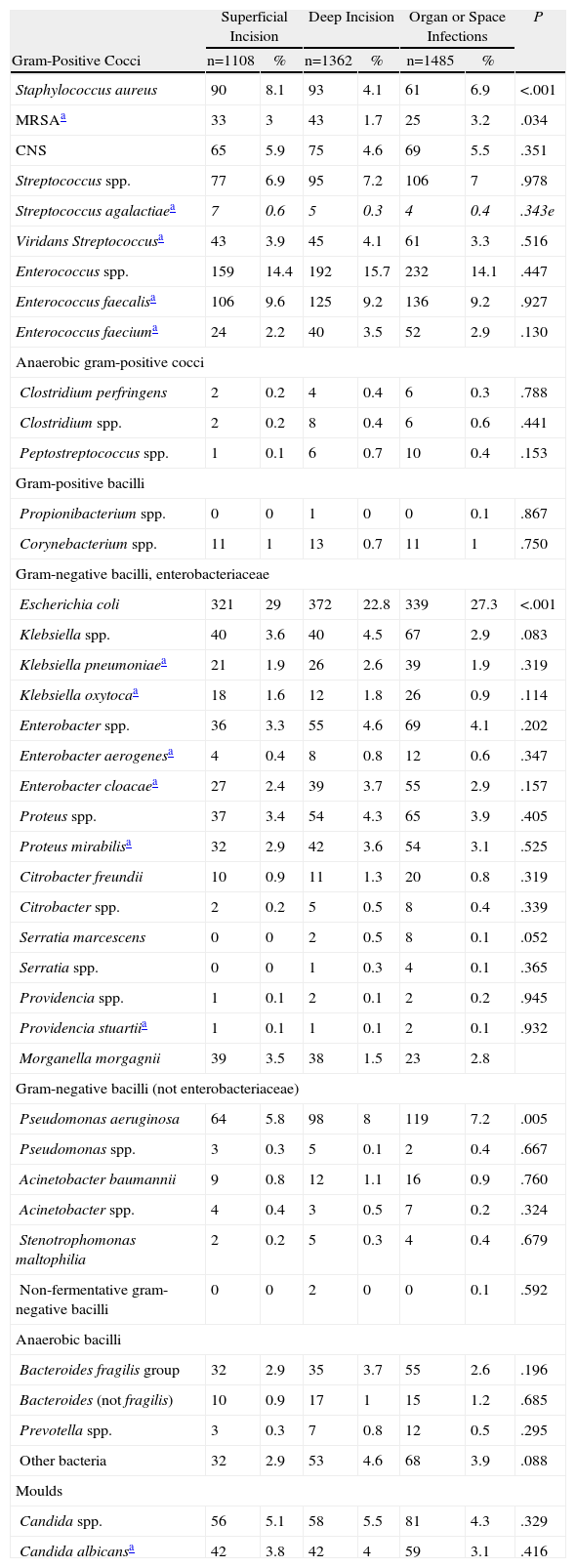

ResultsThe number of Spanish hospitals participating in the EPINE study has increased progressively, exceeding 250 hospitals after 2001. Institutions from all Spanish regions participated in the study. There were 3461 SSI cases detected in the group of patients with abdominal cavity surgery operated upon in general surgery departments, and 3955 microorganisms were isolated. The microbiology test results are detailed in Table 1 by infection location.

Aetiology of Surgical Infections in Patients Undergoing Abdominal Surgery According to Infection Location.

| Superficial Incision | Deep Incision | Organ or Space Infections | P | ||||

| Gram-Positive Cocci | n=1108 | % | n=1362 | % | n=1485 | % | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 90 | 8.1 | 93 | 4.1 | 61 | 6.9 | <.001 |

| MRSAa | 33 | 3 | 43 | 1.7 | 25 | 3.2 | .034 |

| CNS | 65 | 5.9 | 75 | 4.6 | 69 | 5.5 | .351 |

| Streptococcus spp. | 77 | 6.9 | 95 | 7.2 | 106 | 7 | .978 |

| Streptococcus agalactiaea | 7 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.4 | .343e |

| Viridans Streptococcusa | 43 | 3.9 | 45 | 4.1 | 61 | 3.3 | .516 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 159 | 14.4 | 192 | 15.7 | 232 | 14.1 | .447 |

| Enterococcus faecalisa | 106 | 9.6 | 125 | 9.2 | 136 | 9.2 | .927 |

| Enterococcus faeciuma | 24 | 2.2 | 40 | 3.5 | 52 | 2.9 | .130 |

| Anaerobic gram-positive cocci | |||||||

| Clostridium perfringens | 2 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.3 | .788 |

| Clostridium spp. | 2 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.6 | .441 |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. | 1 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.7 | 10 | 0.4 | .153 |

| Gram-positive bacilli | |||||||

| Propionibacterium spp. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | .867 |

| Corynebacterium spp. | 11 | 1 | 13 | 0.7 | 11 | 1 | .750 |

| Gram-negative bacilli, enterobacteriaceae | |||||||

| Escherichia coli | 321 | 29 | 372 | 22.8 | 339 | 27.3 | <.001 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 40 | 3.6 | 40 | 4.5 | 67 | 2.9 | .083 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniaea | 21 | 1.9 | 26 | 2.6 | 39 | 1.9 | .319 |

| Klebsiella oxytocaa | 18 | 1.6 | 12 | 1.8 | 26 | 0.9 | .114 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 36 | 3.3 | 55 | 4.6 | 69 | 4.1 | .202 |

| Enterobacter aerogenesa | 4 | 0.4 | 8 | 0.8 | 12 | 0.6 | .347 |

| Enterobacter cloacaea | 27 | 2.4 | 39 | 3.7 | 55 | 2.9 | .157 |

| Proteus spp. | 37 | 3.4 | 54 | 4.3 | 65 | 3.9 | .405 |

| Proteus mirabilisa | 32 | 2.9 | 42 | 3.6 | 54 | 3.1 | .525 |

| Citrobacter freundii | 10 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.3 | 20 | 0.8 | .319 |

| Citrobacter spp. | 2 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.4 | .339 |

| Serratia marcescens | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.1 | .052 |

| Serratia spp. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.1 | .365 |

| Providencia spp. | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.2 | .945 |

| Providencia stuartiia | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | .932 |

| Morganella morgagnii | 39 | 3.5 | 38 | 1.5 | 23 | 2.8 | |

| Gram-negative bacilli (not enterobacteriaceae) | |||||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 64 | 5.8 | 98 | 8 | 119 | 7.2 | .005 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 3 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.4 | .667 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 9 | 0.8 | 12 | 1.1 | 16 | 0.9 | .760 |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 4 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.2 | .324 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 2 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.4 | .679 |

| Non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | .592 |

| Anaerobic bacilli | |||||||

| Bacteroides fragilis group | 32 | 2.9 | 35 | 3.7 | 55 | 2.6 | .196 |

| Bacteroides (not fragilis) | 10 | 0.9 | 17 | 1 | 15 | 1.2 | .685 |

| Prevotella spp. | 3 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.8 | 12 | 0.5 | .295 |

| Other bacteria | 32 | 2.9 | 53 | 4.6 | 68 | 3.9 | .088 |

| Moulds | |||||||

| Candida spp. | 56 | 5.1 | 58 | 5.5 | 81 | 4.3 | .329 |

| Candida albicansa | 42 | 3.8 | 42 | 4 | 59 | 3.1 | .416 |

MRSA: S. aureus resistant to methicillin; CNS: coagulase-negative staphylococci.

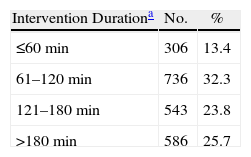

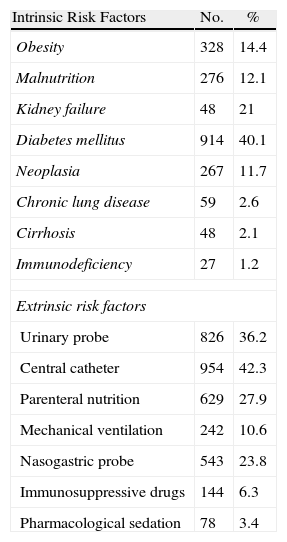

During the study period, 2280 cases of surgical infection were diagnosed, with upper abdominal tract surgery accounting for 833 cases and lower abdominal tract surgery accounting for 1447 cases. The SSI was superficial in 718 patients (31%), deep in 695 patients (30%), and it was an infection in an organ or space, such as peritonitis or intraabdominal abscess, in 866 patients (38%). There were 946 women (41%), and the mean age was 60.9 years (median 67, range 6–97 years). Antibiotic prophylaxis was performed in 78% of patients. The duration of the intervention was greater than 180min in 586 patients (26%, Table 2), and 41% of the patients had an ASA operating risk ≥3. The potential risk factors studied which are associated with hospital surgery are described in Table 3. There were a high proportion of patients suffering from diabetes mellitus (40%), renal failure (21%), obesity (14%) and neoplastic disease (12%). Extrinsic factors present at diagnosis included central venous catheter (42%), urinary catheter (36%), parenteral nutrition (28%), nasogastric probe (24%) and mechanical ventilation (11%), see Table 3.

Surgery Time for Patients Undergoing Upper or Lower Digestive Tract Abdominal Surgery.

| Intervention Durationa | No. | % |

| ≤60min | 306 | 13.4 |

| 61–120min | 736 | 32.3 |

| 121–180min | 543 | 23.8 |

| >180min | 586 | 25.7 |

Risk Factors Associated With Nosocomial Infections in Patients Undergoing Upper or Lower Digestive Tract Abdominal surgery.

| Intrinsic Risk Factors | No. | % |

| Obesity | 328 | 14.4 |

| Malnutrition | 276 | 12.1 |

| Kidney failure | 48 | 21 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 914 | 40.1 |

| Neoplasia | 267 | 11.7 |

| Chronic lung disease | 59 | 2.6 |

| Cirrhosis | 48 | 2.1 |

| Immunodeficiency | 27 | 1.2 |

| Extrinsic risk factors | ||

| Urinary probe | 826 | 36.2 |

| Central catheter | 954 | 42.3 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 629 | 27.9 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 242 | 10.6 |

| Nasogastric probe | 543 | 23.8 |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 144 | 6.3 |

| Pharmacological sedation | 78 | 3.4 |

Some 2617 bacterial species were isolated from the 2280 patients included in the analysis, of which 60% were gram-negative bacilli and 32% gram-positive cocci. The most frequently isolated microorganisms were Escherichia coli (28%), Enterococcus spp. (15%), Streptococcus spp. (8%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7%), coagulase-negative staphylococci (5%), Staphylococcus aureus (5%, 2% were methicillin-resistant), Candida spp. (4%), Klebsiella spp. (4%), Enterobacter spp. (4%), Proteus mirabilis (3%) and Bacteroides fragilis (3%).

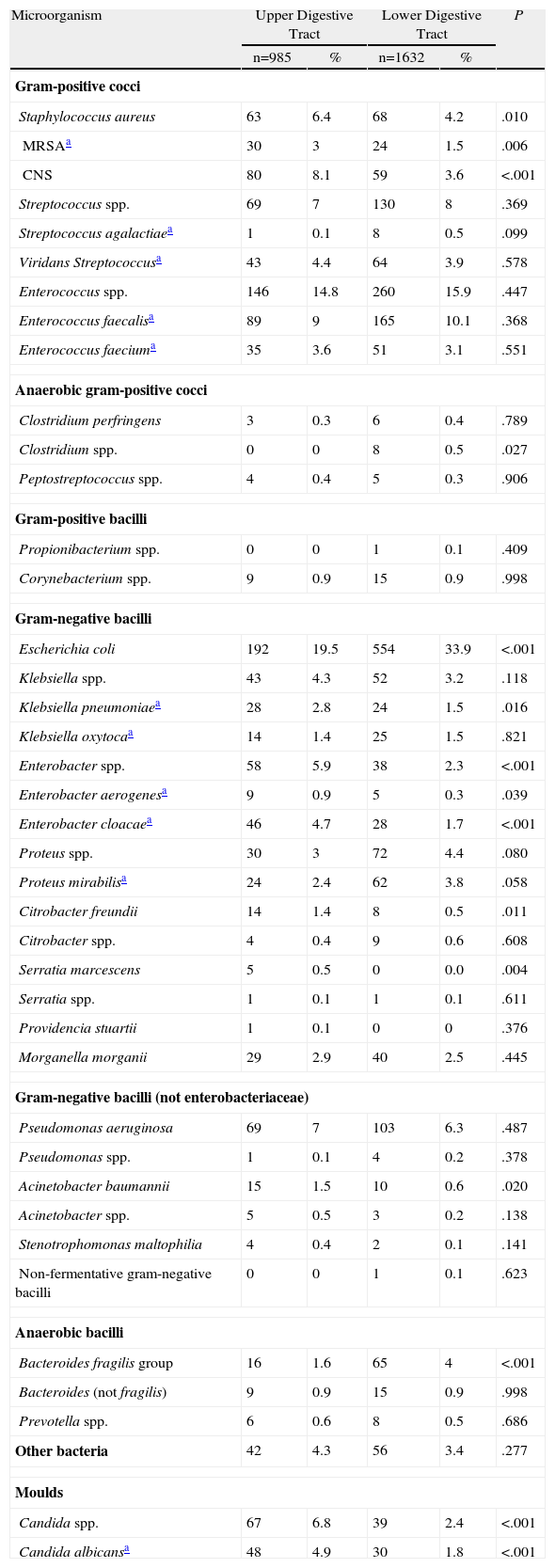

Patients with surgical infection after proximal gastrointestinal procedures had a higher proportion of staphylococci isolates (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Acinetobacter spp. and Candida albicans) and lower proportion of E. coli, B. fragilis and Clostridium spp. (Table 4).

Aetiology of Surgical Infections in Patients Undergoing Upper or Lower Digestive Tract Abdominal Surgery.

| Microorganism | Upper Digestive Tract | Lower Digestive Tract | P | ||

| n=985 | % | n=1632 | % | ||

| Gram-positive cocci | |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 63 | 6.4 | 68 | 4.2 | .010 |

| MRSAa | 30 | 3 | 24 | 1.5 | .006 |

| CNS | 80 | 8.1 | 59 | 3.6 | <.001 |

| Streptococcus spp. | 69 | 7 | 130 | 8 | .369 |

| Streptococcus agalactiaea | 1 | 0.1 | 8 | 0.5 | .099 |

| Viridans Streptococcusa | 43 | 4.4 | 64 | 3.9 | .578 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 146 | 14.8 | 260 | 15.9 | .447 |

| Enterococcus faecalisa | 89 | 9 | 165 | 10.1 | .368 |

| Enterococcus faeciuma | 35 | 3.6 | 51 | 3.1 | .551 |

| Anaerobic gram-positive cocci | |||||

| Clostridium perfringens | 3 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.4 | .789 |

| Clostridium spp. | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0.5 | .027 |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. | 4 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.3 | .906 |

| Gram-positive bacilli | |||||

| Propionibacterium spp. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 | .409 |

| Corynebacterium spp. | 9 | 0.9 | 15 | 0.9 | .998 |

| Gram-negative bacilli | |||||

| Escherichia coli | 192 | 19.5 | 554 | 33.9 | <.001 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 43 | 4.3 | 52 | 3.2 | .118 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniaea | 28 | 2.8 | 24 | 1.5 | .016 |

| Klebsiella oxytocaa | 14 | 1.4 | 25 | 1.5 | .821 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 58 | 5.9 | 38 | 2.3 | <.001 |

| Enterobacter aerogenesa | 9 | 0.9 | 5 | 0.3 | .039 |

| Enterobacter cloacaea | 46 | 4.7 | 28 | 1.7 | <.001 |

| Proteus spp. | 30 | 3 | 72 | 4.4 | .080 |

| Proteus mirabilisa | 24 | 2.4 | 62 | 3.8 | .058 |

| Citrobacter freundii | 14 | 1.4 | 8 | 0.5 | .011 |

| Citrobacter spp. | 4 | 0.4 | 9 | 0.6 | .608 |

| Serratia marcescens | 5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | .004 |

| Serratia spp. | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | .611 |

| Providencia stuartii | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | .376 |

| Morganella morganii | 29 | 2.9 | 40 | 2.5 | .445 |

| Gram-negative bacilli (not enterobacteriaceae) | |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 69 | 7 | 103 | 6.3 | .487 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 1 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.2 | .378 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 15 | 1.5 | 10 | 0.6 | .020 |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 5 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.2 | .138 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 4 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.1 | .141 |

| Non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 | .623 |

| Anaerobic bacilli | |||||

| Bacteroides fragilis group | 16 | 1.6 | 65 | 4 | <.001 |

| Bacteroides (not fragilis) | 9 | 0.9 | 15 | 0.9 | .998 |

| Prevotella spp. | 6 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.5 | .686 |

| Other bacteria | 42 | 4.3 | 56 | 3.4 | .277 |

| Moulds | |||||

| Candida spp. | 67 | 6.8 | 39 | 2.4 | <.001 |

| Candida albicansa | 48 | 4.9 | 30 | 1.8 | <.001 |

MRSA: S. aureus resistant to methicillin; CNS: coagulase-negative staphylococci.

The results obtained from the EPINE study give a global view of the microbiology of postoperative infections in Spanish hospitals.15 The high average age and frequency of concurrent chronic diseases along with extrinsic risk factors highlight the clinical complexity of many cases of abdominal surgical infection.14,18

Among the species isolated from patients with SSI after abdominal surgery are gram-negative bacilli of gastrointestinal origin (aerobic and anaerobic) and gram-positive species, such as streptococci, staphylococci and enterococci, which is consistent with similar studies.19–21 A high proportion of patients who developed enterococcal infection had received cefazolin (which is not active against Enterococcus), which may favour its appearance.14,23,24 Empirical antibiotic coverage for enterococci is considered essential for nosocomial infections, as opposed to that recommended for community-acquired infections.25,26 The proportion of Enterococcus faecium (which is usually resistant to beta-lactams) was higher than that in previous studies.27

A significant proportion of isolates corresponded to pathogens commonly contracted in hospitals, such as gram-negative non-fermenters, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Enterobacter.13,22 In more than 6% of the cultures Pseudomonas were isolated, which is important in the prescription of empirical antibiotic treatment in postoperative abdominal infection cases, especially in patients with risk factors such as prior antibiotic therapy or septic shock.13,28

The microbiology of superficial infection was generally similar to deep infections. The only exception was that infections with S. aureus were more frequent and those with P. aeruginosa less frequent in superficial incisional infections. Also E. coli was isolated less frequently in deep incisional areas than for the other 2 types of infection. However, unlike that observed by other authors, in a large number of patients MRSA infections were found in the organ and space areas.29

The microbiology of surgical infections after upper tract surgery was broadly similar to those after lower digestive tract interventions.30 This result would theoretically justify the use of a similar empirical antibiotic treatment in both circumstances to provide adequate coverage for enterobacteriaceae, anaerobes and enterococci.14 Among the differences found between both groups of infections was a greater presence of staphylococci in upper tract infections.13 Furthermore, the isolation of E. coli and anaerobic bacteria (B. fragilis in particular) was found more often after lower tract surgery. This was expected due to the native flora in each digestive location.30,31 A higher proportion of enterococci infections in the lower tract was not found, as described previously.30,31

The Candida species accounted for 4% of the isolates. They have been associated with stomach and duodenum surgical procedures, anaerobic antibiotic coverage, lack of intra-abdominal focus control and higher mortality.32,33 These yeasts participated more frequently in upper tract surgical procedures than that in lower tract ones, which is consistent with the data in this study.30,32Candida was isolated in a significant proportion of organ and space infections, which confirms the growing importance of fungi in postoperative peritonitis (14%).34 This has prompted the recommendation for empirical use of antifungal agents in patients with risk factors.14,35

The marked diversity of pathogens potentially involved in these infections highlights the risk of inappropriate empirical therapy, which usually occurs in 13%–16% of intra-abdominal infections and could lead to increased mortality.3,36,37 Sometimes this is due to infections caused by resistant gram-negative bacteria (producing extended-spectrum or AmpC beta-lactamases), beta-lactam- or vancomycin-resistant enterococci or Candida.38 The prevalence of AmpC-type beta-lactamases increases after the use of cephalosporins (and other antibiotics) which are generally used in antibiotic prophylaxis. The progressive increase in community-acquired infections caused by ESBL-producing enterobacteria should also be noted.39,40 The most important factor for developing postoperative peritonitis due to multidrug-resistant microorganisms is receiving antibiotic treatment after the initial surgery.12 The prescription of an appropriate empirical regimen in some patients could be a combination of an antipseudomonal carbapenem (with or without aminoglycoside) and a glycopeptide.12,14 However, it is very important to know the epidemiology of each institution to establish the most suitable empirical treatment for each patient.12,14

Being a prevalence study (analysing the number of patients admitted with an infection on a given day), the incidence of these infections could not be obtained, which is one of the limitations of this study. It should also be added that these results may not be applied to specific hospitals, with their individual epidemiological features, as this was a national study. This survey also did not include other variables that may have been of interest, such as smoking use, preoperative stay, type of antibiotic prophylaxis administered, degree of compliance with adequate preoperative preparation or the NNIS index. In addition, the relationship between infection aetiology and pre-surgery antibiotic treatment or the degree of contamination was not able to be analysed. The microbiology of infections in patients undergoing elective surgery was not able to be compared with that for urgent surgery or that related to reinterventions. These may be caused by nosocomial microorganisms, with increased antimicrobial resistance. Another limitation is that infections after hepatobiliary surgery were not independently studied. These may present significant differences to those produced in other types of upper digestive tract interventions.

In conclusion, the microbiology of SSI occurring after upper gastrointestinal interventions showed no marked differences to those in the lower tract. However, more cases of SSI were detected due to staphylococci, K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Acinetobacter spp. and C. albicans, and less were caused by E. coli, B. fragilis and Clostridium spp. The information obtained from this study allows a better understanding of the aetiology of surgical infections in patients undergoing abdominal surgery, which may have epidemiological and therapeutic implications.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please, cite this article as: Múnez E, et al. Microbiología de las infecciones del sitio quirúrgico en pacientes intervenidos del tracto digestivo. Cir Esp. 2011;89:606–12.