Organizations rely on contextual factors to promote employee disclosure of self-made errors, which induces a resource dilemma (i.e., disclosure entails costing one's own resources to bring others resources) and a friendship dilemma (i.e., disclosure is seemingly easier through friendship, yet the cost of friendship is embedded). This study proposes that friendship at work enhances error disclosure and uses conservation of resources theory as underlying explanation. A three-wave survey collected data from 274 full-time employees with a variety of occupational backgrounds. Empirical results indicated that friendship enhanced error disclosure partially through relational mechanisms of employees’ attitudes toward coworkers (i.e., employee engagement) and of coworkers’ attitudes toward employees (i.e., perceived social worth). Such effects hold when controlling for established predictors of error disclosure. This study expands extant perspectives on employee error and the theoretical lenses used to explain the influence of friendship at work. We propose that, while promoting error disclosure through both contextual and relational approaches, organizations should be vigilant about potential incongruence.

Every organization is confronted with employee errors (Dyck et al., 2005, p.1228). Indeed, human errors are unavoidable; in every organization, they are a challenge that can potentially harm performance (Hofmann and Frese, 2011). Thus, in addition to preventing errors, organizations develop systematic approaches to detecting them. Furthermore, because human errors per se will never be totally predictable, organizations rely on employees to voluntarily disclose errors, however employees often do not disclose their own errors (Dyck et al., 2005; Gold et al., 2014; Zhao and Olivera, 2006). This study focuses on the issue of employee disclosure of self-made errors (hereafter, simply “error disclosure”, meaning that employees voluntarily speak out about self-made errors) and aims to understand whether error disclosure is enhanced by friendship at work.

Although essential to organizations, error disclosure is costly from a social and a personal perspective. The social cost of error disclosure is its harm to workplace image. Error disclosure damages employee images on job competence, attitudes or involvement (Dyck et al., 2005; Gronewold et al., 2013; Uribe et al., 2002). Since workplace image facilitates job continuance and development and is an important job resource (Cheng et al., 2014), error disclosure induces a loss of image resource. The personal cost of error disclosure is that error disclosure consumes both time and energy resources at work, both of which are required to report and explain errors (Dyck et al., 2005; Gronewold et al., 2013; Uribe et al., 2002). Based on Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, according to which people are motivated by resource protection and resource-loss avoidance (Hobfoll, 1989), employees are unwilling to disclose errors because they seek to avoid resource losses.

The error literature indicates that organizations expend efforts to create cultures/climates that decrease the social cost of error disclosure and to enact rules and procedures to decrease the personal cost of error disclosure. However, such efforts seem to have limited effects (Dyck et al., 2005; Gold et al., 2014; Uribe et al., 2002) because employees suspect that the “error anti-aversion” culture/climate is paid “lip service” to by the organization (Dyck, 1997, 2009; Dyck et al., 2005). For example, non-punishment of error occurrence is not provided, new errors are accepted, but repeated errors are likely to invoke some sanctions, and employees recognize fundamental attribution bias and hindsight bias to follow error disclosure (Dyck, 2009; Dyck et al., 2005; Gronewold et al., 2013). Thus, while organizational antecedents have been focused to encourage employees’ disclosure of error, individual factors of employees merit attention as a complementary means of encouraging such disclosure. Notably, employees’ concern for social cost of error disclosure is widely documented to result in their error non-disclosure (Zhao and Olivera, 2006). Since social cost at work relates to workplace social relationships and literature indicates that these relationships influence employee actions (Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001) and include work relationships (i.e., a work-role bond) and friendships (i.e., a personal bond) (e.g., Berman et al., 2002; Morrison and Wright, 2009; Sias and Cahill, 1998), the question arises whether the friendships employees develop at work (hereafter, simply “friendships”) relate to error disclosure.

Friendship is a basic value of human nature (Wright, 1984) and the development of friendships at work is prevalent (e.g., Berman et al., 2002; Sias and Cahill, 1998). Although friendship influences the disclosure of information (Berman et al., 2002; Morrison and Wright, 2009; Sias and Cahill, 1998), it is impossible to determine friendship's effect on error disclosure because of the friendship dilemma at work (Bridge and Baxter, 1992), i.e., friendship leads employees to expect more mutual acceptance; yet, it also leads to conflict or critical evaluation because work roles generate competing interests (Bridge and Baxter, 1992; Sias and Cahill, 1998). Expectably, the mutual acceptance that is part of friendship mitigates the social cost (to one's image) of error disclosure, consequently making employees more willing to disclose errors. However, conflict with or critical evaluation from friendship may render that social cost vexatious and hence hinder error disclosure. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that error disclosure is related to friendship, yet the nature of this relation is ambiguous, and this study has an aim of examining the effect of friendship on error disclosure. Moreover, literature indicates that although research has much examined the effects of workplace friendship, it falls short of the dynamics through which friendships produce those effects (Dotan, 2009; Methot et al., 2016). Thus, the secondary aim of this study is to highlight the intervening mechanisms of the effect studied.

Specifically, the few studies on the explanatory mediators for the effects of workplace friendship have focused on the mediating factors of individual or job attitudes and behaviors (e.g., affect/emotion, exhaustion, job involvement/satisfaction, organizational commitment and citizenship behavior; Dotan, 2009; Methot et al., 2016; Morrison, 2004), while research on workplace friendship has predominantly applied a social capital lens and has an emphasis on relational benefits (Methot et al., 2016). Thus, this study intends to highlight the explanatory mediators from relational mechanisms. Besides, friendship is part of social environment in the workplace. Literature on that social environment has called for more attention to the relational mechanisms for explaining the consequences of that environment (e.g., Grant, 2008) because relational mechanisms, which are processes that influence employees’ connections to others in their organizations (Holmes, 2000), fulfill employees’ basic motives of experiencing their actions as related and connected to their coworkers (Baumeister and Leary, 1995).

Friendships provide such a connection of relational mechanisms by affecting the attitudes of employees toward their coworkers and those of their coworkers toward them (e.g., Berman et al., 2002; Morrison and Wright, 2009; Sias and Cahill, 1998). These attitudes understandably affect whether employees go the extra mile to risk losing resources and to disclose errors, as noted earlier. This resource perspective elicits the notions that employees’ attitudes toward their coworkers will relate to their resource investments at work (Berman et al., 2002; Methot et al., 2016; Sias and Cahill, 1998) (i.e., employee engagement; Kahn, 1990), and that how coworkers value their actions (i.e., perceived social worth; Grant, 2008) will be the responsive attitudes of coworkers toward them. Prior study has presented perceived social worth as a significant relational mechanism for employees (Grant, 2008) and this study introduces employee engagement as a new mechanism. Together, we include the relational factors of employee engagement and perceived social worth as potential mediators for the friendship-error disclosure relationship.

This study advances the current understanding of friendship's facilitation of work-related and non-work-related information exchange (Berman et al., 2002; Sias and Cahill, 1998) by looking at a distinct type of information: self-made errors, which create social costs for and are detrimental to the information providers themselves. Discerning whether friendship facilitates or hinders error disclosure contributes to the friendship literature with regard to friendship's benefits and disadvantages in organizations. Furthermore, that literature indicates that although the individual and organizational outcomes of friendship have been much evidenced, more attention to the dearth of a clear explanation for why friendships produce those outcomes is needed and more research is needed to gain understanding of the friendship effects (Dotan, 2009; Methot et al., 2016). Consistent with that call, this study includes the relational factors of employee engagement and perceived social worth for mediating the friendship effect and serves to contribute to the literature by understanding how and why friendships affect error disclosure.

Error disclosure is distinct from two related constructs. First, despite the organizational need for error information (Dyck et al., 2005), not disclosing errors differs from hiding knowledge (Connelly et al., 2012) because the latter does not involve avoiding the social cost of one's image, while the former does. Second, error disclosure differs from employee voice. This voice is focused on speaking up to persons at work who have authority/power to take actions (Morrison, 2014; Zhang et al., 2015), while such focus is scarcely specified in error disclosure literature, which has much investigated the disclosure to coworkers (Cannon and Edmondson, 2001; Cigularov et al., 2010; Dyck et al., 2005; Hofmann and Mark, 2006; Rybowiak et al., 1999). Besides, the content of employee voice is workplace issues or others’ actions that the employee perceives as needing improvement (Morrison, 2014; Zhang et al., 2015), while that in error disclosure is disclosers’ self-made errors. Moreover, error disclosure involves the social cost of damaged images (e.g., poor competence/attitudes/involvement) imposed on disclosers, while such cost seems hardly considered in employee voice since the purpose of voice is to help organizations with the identification of organizational problems overlooked by managers/supervisors and generate improvements in organizational functions (Ng and Feldman, 2012). Thus, in addition to the research on employee voice, there is another stream of research focusing on the issue of error disclosure (Dyck et al., 2005; Rybowiak et al., 1999; Zhao and Olivera, 2006), to which this study aims to contribute.

As noted above, error research shows that organizations employ contextual strategies to promote error disclosure and more investigation into the influence of individual differences is needed for the promotion of error disclosure (Zhao and Olivera, 2006). This study complements that research by studying friendship – a likely alternative factor related to error disclosure – and focuses on this individual and salient factor in an organization because individuals are the parsimonious unit of an organization and can best discern the micro-problems least identified in an organization.

Theory and hypothesesError disclosure is related to resource losses at work, as noted earlier, and workplace friendships have been documented to be related to resources at work (e.g., Methot et al., 2016; Sias and Cahill, 1998). Thus, the view of resources and COR theory are linked to friendship and error disclosure to underlie our rationale for the friendship-error disclosure relationship.

Errors and error disclosure at workErrors are unintended deviations from standards, rules, plans, procedures, goals, or a code of behavior (Dyck et al., 2005; Zhao and Olivera, 2006). The errors in this study refer to (1) errors that individual employees make at work and (2) errors that employees have the discretion to disclose (Zhao and Olivera, 2006); i.e., if an error maker does not disclose an error himself/herself, neither other people nor systems can become aware of his/her having made that error. Errors at the group or organizational levels (Hofmann and Frese, 2011) are beyond the scope of this study.

Although error has negative consequences for organizations (e.g., time, cost, reputation, product quality), it can promote learning that benefits organizations by, for example, decreasing the probability and consequences of error reoccurrence and increasing adaptation, innovation, and resilience (Dyck et al., 2005; Hofmann and Frese, 2011). We posit that error is a valuable and unique job resource for error makers because of its knowledge-providing and routine-breaking nature. Specifically, organizations have two error mechanisms: (1) error prevention, including all imaginable approaches to blocking erroneous actions whenever possible; and (2) error management, ensuring that all imaginable errors are quickly detected and reported, negative consequences are minimized, and learning effects are recognized (Dyck et al., 2005; Hofmann and Frese, 2011). Under these two error mechanisms, employees can still make errors, which suggests that such errors are neither covered by the error prevention mechanism nor detectable by the error management mechanism. Error is valuable because only the error maker knows its content, time, place and contextual condition; this includes the error maker's knowledge of the error's existence, detection, prevention, correction and learning effect. Thus, error can be a source of knowledge about job performance and competence.

Because error occurrence is accidental, unintentional and unpredictable (Hofmann and Frese, 2011), error interrupts work regularity and employees need unusual or new perceptions or actions to address error correction and/or negative consequences (e.g., Brodbeck et al., 1993; Dyck et al., 2005; Gold et al., 2014). That is, both the occurrence and tackling of errors are unusual things and inject variety into routine work processes, fostering a sense of variety at work. Error can introduce a break in prescribed work procedures and cause employees to take another look at their work. In summary, error can be a source of routine-breaking that stimulates variety of thought or action.

In short, error experiences can be valuable sources of job knowledge and routine-breaking for error makers with regard to their job performance and competence, i.e., error can be functional in stimulating personal growth/development and achieving work goals. According to COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001), this indicates that error is a job resource. As noted above, coworkers can derive the benefits of error only if error makers disclose their own errors. Hence, for error makers error is valuable and unique job resources of knowledge learning and routine-breaking stimulation.

This job resource perspective on error imports that error disclosure is a resource sharing. Although sharing of error information is needed by organizations (e.g., Dyck et al., 2005; Gold et al., 2014), there are hindrances to error disclosure. Specifically, it is recognized that consideration of costs is central in people's taking discretionary behaviors at work (Morrison and Phelps, 1999). Accordingly, whether error-making employees voluntarily disclose their errors involves the cost of this disclosure. We propose that error disclosure will be hindered by two costs: loss of exclusiveness of error resources and loss of image resource. First, people are generally reluctant to share unique resources with others because they prefer to exclusively own their advantages in order to maximize self-interest. This is based on the long-standing recognition that self-interest is a powerful human motive that accounts for much of human survival and success (Kish-Gephart et al., 2014, p.267). Thus, employees will try to keep the unique job resources of error exclusive and will be reluctant to share, i.e. disclose, their error. In other words, loss of exclusiveness of error resources (i.e. job knowledge learning and routine-breaking simulation, stated above) is a hindrance to the sharing of error resource, i.e. error disclosure.

Second, error disclosure damages error makers’ image on job competence, attitudes or involvement (Dyck et al., 2005; Gronewold et al., 2013; Uribe et al., 2002). Employee image is a job resource because it facilitates the employee's performance and development in the organization (Cheng et al., 2014). Hence, employees will be reluctant to share, i.e. disclose, their error in order to avoid losing image resource. In other words, loss of image resource is a hindrance to the sharing of error resource, i.e. error disclosure. In summery, two hindrances—loss of exclusiveness of error resources and loss of image resource—will prevent employees from error resource sharing, i.e. error disclosure, and need to be overcome to promote error disclosure.

It is understandable that there should be common work knowledge and routines/procedures across jobs to evoke the knowledge learning and routine-breaking stimulation that errors can produce. Therefore, in this study we measure an individual employee's perception of friendship and error disclosure in his/her team or work-unit. This approach is underlined by the call of employees for higher relationship quality at work, which involves individual employees’ perceptions of workplace friendship within their work-units (Tse et al., 2008).

Friendship in work organizationsStudies of the social environment at work have generally classified interpersonal relationships as work relationships and friendships1 (Bridge and Baxter, 1992; Sias and Cahill, 1998). A work relationship is a work-role bond, a view of partners as mere role occupants in organizations (Bridge and Baxter, 1992; Morrison and Wright, 2009; Sias and Cahill, 1998): it entails an organizational-role view, stems from work-related concern, and is prescribed by job design or considered necessary for job achievement, work-role needs or work/organization goals. In contrast, friendship develops at the discretion of employees (Bridge and Baxter, 1992; Morrison and Wright, 2009; Sias and Cahill, 1998) and the partners interact freely with one another without constraints/pressures external to the relationship itself (Wright, 1984). Friendship is perceived as a personal bond; it entails a personalistic view as well as interactions based on personal concern in order to satisfy the personal needs of self and partners (Bridge and Baxter, 1992; Morrison and Wright, 2009; Sias and Cahill, 1998). In friendship, individuals’ commitments to one another take precedence over fulfilling work/organization-related needs (Wright, 1974). Hence, the influence of friendship on employees will differ from that of work relationship, and, in the organizational research on relationships, there is an arena focusing on friendship issues (Methot et al., 2016; Morrison and Wright, 2009).

Friendship is a personal bond. More insightfully, friendship entails self-referent motivation, incorporation of friendship as a self-attribute, and shared identity and values (Wright, 1984). This suggests that friendship embeds personal feeling and value of us (i.e., self and partners); we posit this as friendship favoritism of us at work and propose that it promotes employees’ actions for the good of us, in addition to their usual actions for their own good. Given this favoritism of us, friendship will lead employees to favor their partners by providing more resources than those prescribed formally or required for the job/organization in a work relationship (Berman et al., 2002; Bridge and Baxter, 1992; Sias and Cahill, 1998). Literature indicates that those who provide help (, which imports resource-providing,) are perceived to have knowledge, expertise, accessibility, trustworthiness, or status/standing (Hofmann et al., 2009; Nadler et al., 2003). Friendship leads employees to receive these benefits, which function as work resources because they assist in achieving work goals, reducing job demands, or stimulating personal growth and development; COR theory posits that an object or condition with such attributes is a job resource (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001). In summary, friendship entails favoritism of us and leads to the accrual of resource gains at work.

Friendship and error disclosureThe social cost of error results in error non-disclosure, and error makers will disclose errors only once they are confident that they will not suffer unfavorable consequences (Zhao and Olivera, 2006). In other words, trust (Halbesleben and Wheeler, 2015) exists among coworkers before they disclose errors. Trust encourages people to speak up with information that they are unwilling to make public (Smetana et al., 2006), and friendship has a trust component (Morrison and Wright, 2009). Therefore, we posit that trust in a friendship will enable employees to disclose error; however, it does not enhance error disclosure. This is the same as the situation that people generally trust their teachers, lawyers, doctors, policemen, and priests, but they do not consequently disclose all relevant information to them. Therefore, it is unlikely to solely rely on trust to enhance error disclosure, and we propose friendship favoritism as described below.

As noted earlier, friendship favoritism of us will lead employees to give the favor of providing more resources than those required or needed for the job/organization in work relationship. In other words, friendship favoritism of us will elicit the favor of sharing unique job resources that are often not provided in work relationship. Employees are often not willing to disclose their error in work relationship (e.g., Dyck et al., 2005; Zhao and Olivera, 2006) and error is valuable and unique job resources of knowledge learning and routine-breaking stimulation. Accordingly, the friendship favor of sharing unique job resources will include the sharing of error resource, thus diminishing the reluctance that prevents employees from sharing their error resource in order to retain its benefits exclusively for themselves and to avoid loss of image resource. Therefore, friendship will facilitate error disclosure.

Further, COR theory can be used to address the hindrances to error disclosure. COR theory indicates that those with more resources are less vulnerable to resource loss (Hobfoll, 2001) and that a gain in resources will help offset a loss (Hobfoll, 1989). Accordingly, because friendship leads employees to accrue more resource gains as aforementioned, it will make resource losses from error disclosure (i.e. loss of exclusiveness of error resources and loss of image resource) more affordable and hence facilitates error disclosure. We proposeHypothesis 1 Friendship at work has a positive relationship with error disclosure.

We specify below the relational mechanisms of employee engagement and perceived social worth as potential mediators of the relationship studied and both factors have been identified as significant mediators for the effect of employee perceptions/attitudes on individual outcomes (e.g., Grant, 2008; Saks, 2006). Employee engagement means that an employee is psychologically present at work and, in other words, invests himself/herself at work (Kahn, 1990, 1992), and it can be in doing the job (i.e., job engagement) or being a member of the workplace (i.e., organization engagement) (Saks, 2006). Since the antecedent of employee engagement in this study is friendship, which is an employee's interpersonal relationship in the workplace, this study adopts employee engagement in being a member of the workplace.

In light of the preceding arguments that friendship favoritism of us embeds more value of us (i.e., oneself and partners), promotes actions for the good of us and will provide more resources than job/organization needs, friendship will understandably induce employees to be more psychologically present at work and, in other words, to invest more of themselves at work (Kahn, 1990, 1992). Further, as reasoned previously, the favoritism of friendship leads to more resource gains and, according to COR theory, those with more resources are more capable of resource investment, while those with fewer resources will avoid consumption of their limited existing resources (Hobfoll, 2001). Accordingly, friendships will allow employees to invest more of themselves at work. In view that employees’ investing themselves at work is referred to as employee engagement (Kahn, 1990, 1992), we expect that friendship will increase employee engagement.

Employee engagement can be negatively related to silence at work, i.e., employees with high engagement may take risks to do the job right and may speak up for improvements at work because they are personally involved (Knoll and Redman, 2015). Similarly, more highly engaged employees have more active, self-starting (i.e., discretionary) behaviors which contribute ultimately (Kahn, 1990; Rich et al., 2010). Accordingly, since error disclosure is discretionary, has the risks of losing exclusiveness of error resources and losing image resource, but ultimately contributes by providing improvement through sharing the valuable, unique job resources of error (i.e., job knowledge learning and routine-breaking stimulation), employee engagement will promote error disclosure.

COR theory can be used to address the hindrances to error disclosure. Employee engagement at work has been shown to be a positive affective state, which broadens people's modes of thinking and action and, over time, builds their enduring resources, such as autonomy, coaching, feedback, coworker support, self-efficacy, organization-based self-esteem and optimism (e.g., Fredrickson, 2001; Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). COR theory posits that people with more resources will be less vulnerable to resource loss (Hobfoll, 2001) and that a gain in resources will help offset a loss (Hobfoll, 1989). Accordingly, as employee engagement can build more resources, it will render resource losses from error disclosure (i.e. loss of exclusiveness of error resources and loss of image resource) more affordable and therefore facilitates error disclosure. We proposeHypothesis 2 Employee engagement partially mediates the relationship between friendship at work and error disclosure.

Perceived social worth refers to employees’ perceptions that their actions are appreciated and valued by their coworkers (Grant, 2008). In light of prior findings that employee actions with positive influence do not necessarily receive appreciation from coworkers (Cheuk et al., 1998; Fisher et al., 1982), and in light of the preceding arguments that friendship favoritism is volunteered out of personal concern rather than job/organizational need and that actions in a friendship will be viewed as concern for the partners per se more than for the work/organization, we argue that employee actions in a friendship will be more appreciated and valued than those in a work relationship. In short, friendship will lead to higher perceived social worth.

Humans have an intrinsic motivation to pursue social worth (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). Thus, when employees feel that their actions are appreciated/valued, they will invest more time and energy in actions that they consider will contribute at work (Grant, 2008; Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002). Accordingly, because error disclosure is a contributing action, i.e., it shares the valuable, unique job resources of error (i.e., job knowledge learning and routine-breaking stimulation), employee perception of higher social worth will lead to more error disclosure.

COR theory can be used to address the hindrances to error disclosure. Employee perception of being appreciated and valued by coworkers (i.e., perceived social worth) results in a positive affective state (Ersner-Hershfield et al., 2008; Parry and Kalisch, 2012), which, as indicated in the rationale of Hypothesis 2, will build resource gain. COR theory posits that people with more resources will be less vulnerable to resource loss (Hobfoll, 2001) and that a gain in resources will help offset a loss (Hobfoll, 1989). Accordingly, as perceived social worth can build more resources, it will render resource losses from error disclosure (i.e. loss of exclusiveness of error resources and loss of image resource) more affordable and hence facilitates error disclosure. We proposeHypothesis 3 Perceived social worth partially mediates the relationship between friendship at work and error disclosure.

The data for this study came from a three-wave survey study conducted during an eight-week period in August and September of 2014. The sample was recruited either with the assistance of workers’ employers or through full-time employees attending evening MBA classes at a large university in northern Taiwan. A pilot study was conducted with 30 full-time employees attending night classes at a large university in northern Taiwan for the purpose of obtaining feedback concerning the clarity of the instructions and questions in the questionnaire and to fine-tune the presentation of the questionnaire. All the measurement items in the questionnaire were responded to using a five-point Likert scale format ranging from (1) ‘strongly disagree’ to (5) ‘strongly agree’.

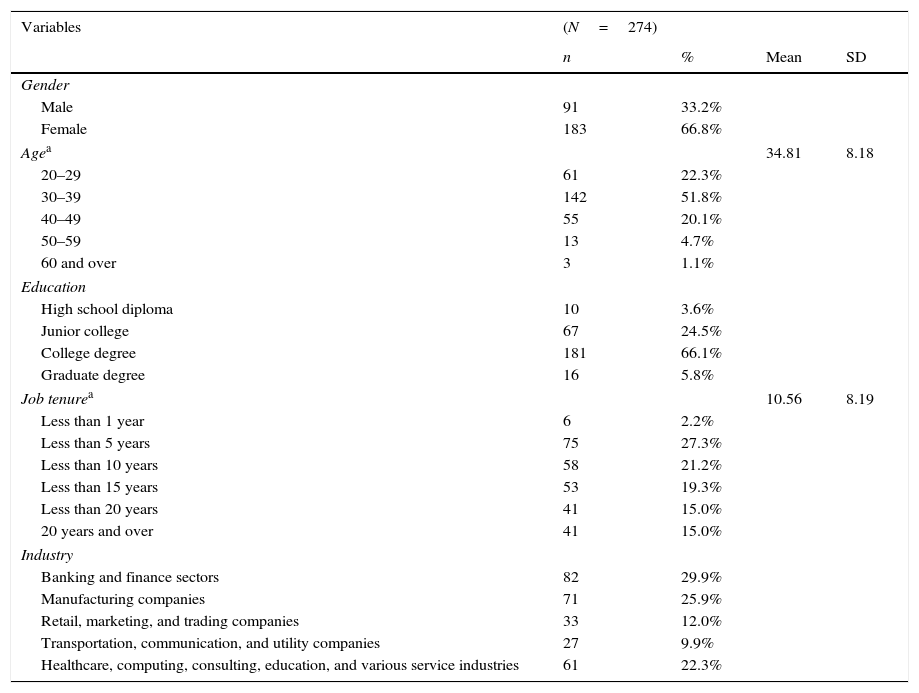

We adopted the three-wave survey design to be much less subject to common method bias caused by the self-reported measures (Podsakoff et al., 2003), which are by definition necessary because the concepts specified below are perceptual measures (Lievens et al., 2007). Questionnaires were distributed to 600 full-time employees in Taiwan with a variety of occupational backgrounds. A total of 482 employees answered the three questionnaires, out of which 274 employees provided complete answers, yielding a final response rate of 45.7%. Table 1 provides a demographic breakdown of the 274 respondents.

Characteristics of the sample.

| Variables | (N=274) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Mean | SD | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 91 | 33.2% | ||

| Female | 183 | 66.8% | ||

| Agea | 34.81 | 8.18 | ||

| 20–29 | 61 | 22.3% | ||

| 30–39 | 142 | 51.8% | ||

| 40–49 | 55 | 20.1% | ||

| 50–59 | 13 | 4.7% | ||

| 60 and over | 3 | 1.1% | ||

| Education | ||||

| High school diploma | 10 | 3.6% | ||

| Junior college | 67 | 24.5% | ||

| College degree | 181 | 66.1% | ||

| Graduate degree | 16 | 5.8% | ||

| Job tenurea | 10.56 | 8.19 | ||

| Less than 1 year | 6 | 2.2% | ||

| Less than 5 years | 75 | 27.3% | ||

| Less than 10 years | 58 | 21.2% | ||

| Less than 15 years | 53 | 19.3% | ||

| Less than 20 years | 41 | 15.0% | ||

| 20 years and over | 41 | 15.0% | ||

| Industry | ||||

| Banking and finance sectors | 82 | 29.9% | ||

| Manufacturing companies | 71 | 25.9% | ||

| Retail, marketing, and trading companies | 33 | 12.0% | ||

| Transportation, communication, and utility companies | 27 | 9.9% | ||

| Healthcare, computing, consulting, education, and various service industries | 61 | 22.3% | ||

Non-response bias was tested by comparing the responses of late respondents to those of early respondents (Armstrong and Overton, 1977). The analyses showed there was not a significant difference between the early 30 and the late 30 respondents in terms of gender (X2=3.35, p>.05), age (t=.53, p>.05), education (X2=5.42; p>.05), and job tenure (t=.54; p>.05). Thus, there was a low likelihood of non-response bias.

Time 1 measuresThe first wave of the survey collected data for the independent and control variables. Friendship at work was measured with the 6-item scale (as presented in Appendix A) developed by Nielsen et al. (2000), which has been much used in previous studies (e.g., Mao, 2006; Mao et al., 2012; Tse et al., 2008). Sample items were “I have formed strong friendships at work” and “I do not feel that anyone I work with is a true friend” (reverse-coded). All the factor loadings (ranging from .58 to .83) of the 6 items exceeded the acceptable value of .50. Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted for the scale were .88, .89, and .82, respectively.

Because prior studies had found them to affect the error discussions of employees (Cannon and Edmondson, 2001; Edmondson, 1999; Rybowiak et al., 1999), both supportive organizational context and psychological safety were included as control variables. Supportive organizational context was measured with a 5-item scale (Edmondson, 1999), as presented in Appendix A, and sample items were “In my work organization, it is easy for me to obtain expert assistance when something comes up that I do not know how to handle” and “I am kept in the dark about current developments and future plans that may affect my work” (reverse-coded). All the factor loadings (ranging from .59 to .87) of the 5 items exceeded the acceptable value of .50. Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted for the scale were .81, .87, and .78, respectively. Psychological safety was measured with a 4-item scale (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2006), as presented in Appendix A, and sample items were “In my work organization, I am able to bring up problems and tough issues” and “It is difficult to ask other members for help” (reverse-coded). All the factor loadings (ranging from .58 to .84) of the 4 items exceeded the acceptable value of .50. Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted for the scale were .82, .82, and .72, respectively.

Time 2 measuresTime 2 occurred 3 weeks after time 1 and collected data for the mediating variables. Employee engagement in the work-unit was measured with a 6-item scale, which measured employee engagement in the organization (Saks, 2006) and was adapted for use in the work-unit. Sample items were “One of the most interesting things for me is getting involved with the things happening in this work-unit” and “I am really not into the ‘goings-on’ in this work-unit” (reverse-coded). All of the employee engagement items except one had the factor loadings higher than the acceptable value of .50 (ranging from .56 to .80). The one item had the factor loading below 0.50 and thus was removed from the employee engagement scale, resulting in a 5-item scale (as presented in Appendix A). Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted for the scale were .82, .82, and .68, respectively.

Perceived social worth was measured with a 3-item scale, as presented in Appendix A. Two of the 3 items were from Grant (2008), and the other one was designed as a reverse-coded item for this study. Sample items were “I feel coworkers value my contribution at work” and “I do not feel coworkers appreciate my effort” (reverse-coded). All the factor loadings (ranging from .67 to .77) of the 3 items exceeded the acceptable value of .50. Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted for the scale were .83, .77, and .64, respectively.

Time 3 measuresTime 3 occurred 3 weeks after time 2 and collected data for the dependent variable. Error disclosure was measured with a 3-item scale (Rybowiak et al., 1999), as presented in Appendix A. Sample items were “When I make an error at work, I tell coworkers” and “I would rather keep my errors at work to myself” (reverse-coded). All the factor loadings (ranging from .70 to .85) of the 3 items exceeded the acceptable value of .50. Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted for the scale were .83, .83, and .75, respectively.

Data analysesThe possibility of common method bias was also examined using (in addition to the three-wave survey design) the statistical approach of Harman's one factor test (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). A principal component factor analysis on the items measured yielded six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and accounted for 65.84% of the variance. Six factors, rather than one single factor, were identified, and the first factor did not account for a large percentage of the variance (16.18%). Hence, common method variance was not a serious problem in this study. In addition, using AMOS, we employed confirmatory factor analysis (Korsgaard and Roberson, 1995) to test the fit of a one-factor model (all items were loaded on a common factor) and a six-factor model (workplace friendship, error disclosure, employee engagement, perceived social worth, supportive organizational context and psychological safety). The data showed that the six-factor model had a better fit (X2/df=3.35, PGFI=.65, PNFI=.67, and PCFI=.73) than the one-factor model (X2/df=6.07, PGFI=.51, PNFI=.46, and PCFI=.50), indicating a little chance of having common method problems.

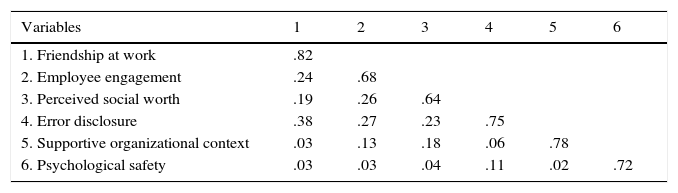

As indicated above, the factor loadings for all items exceeded the acceptable value of .50, all composite reliabilities exceeded the threshold value of .60, and the average variance extracted for all constructs exceeded the benchmark of .50 (Fornell, 1982). Thus, the scales used in measuring those constructs were deemed to have satisfactory convergence reliability. The squared correlations among constructs were less than the variances extracted by the constructs, as presented in Appendix B. This showed that the constructs were empirically distinct (Fornell, 1982). Thus, the convergent and discriminant validity measures were satisfactory. Besides, as a check for multicollinearity, the VIF scores were calculated for the variables and then checked to ensure that all the VIF scores were below 10.0 (Hair et al., 1995). The result that all VIF scores were from 1.06 to 1.62 suggested that multicollinearity was not a serious problem in this study.

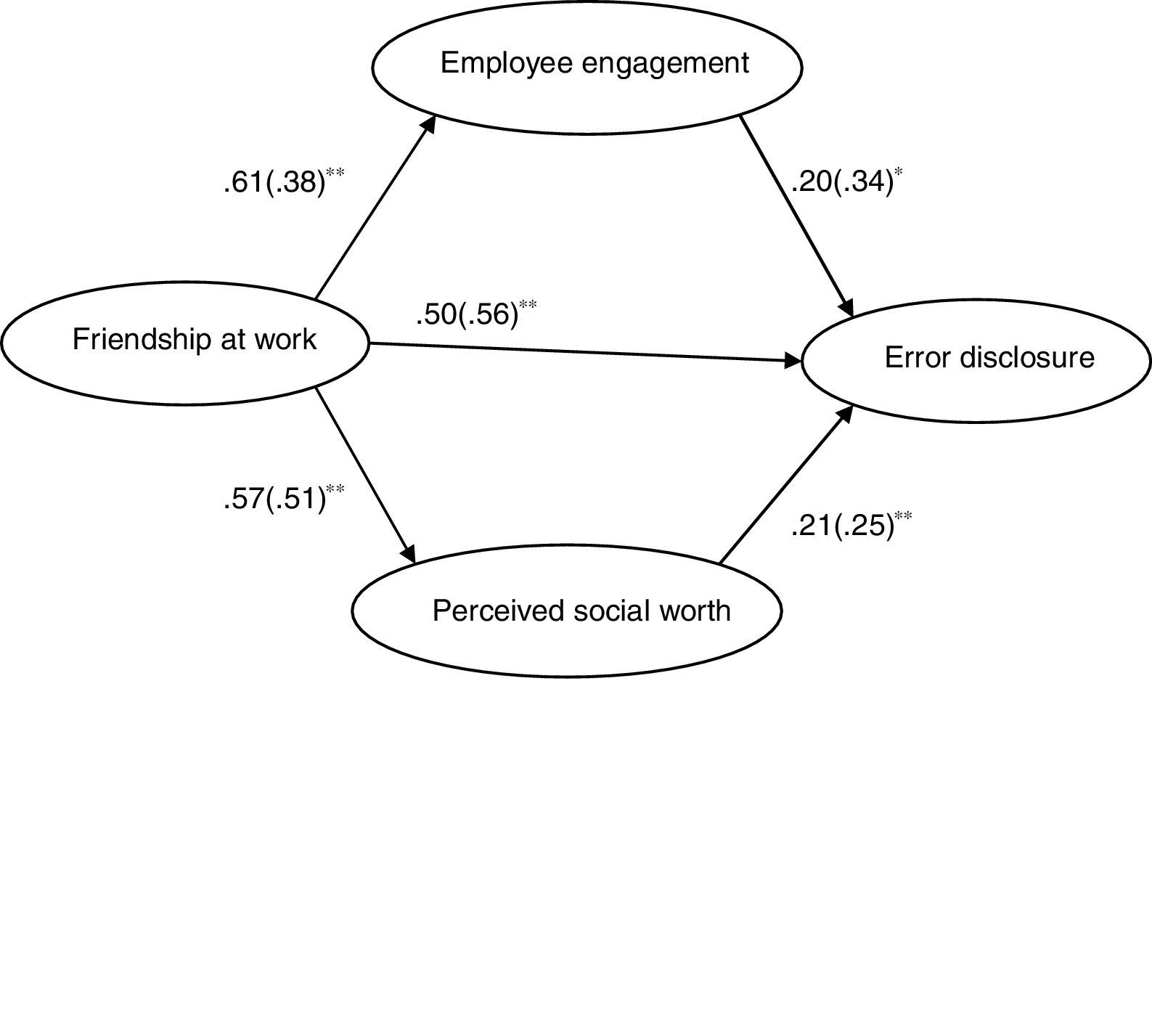

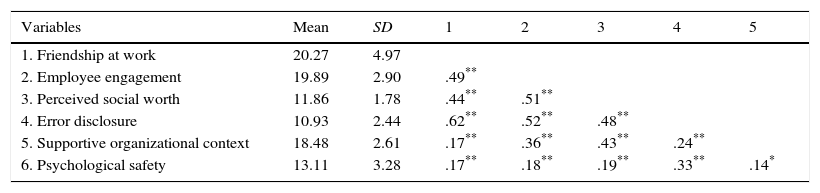

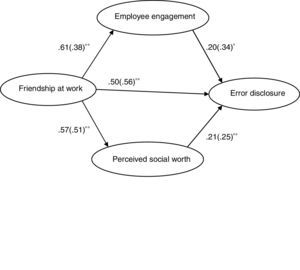

ResultsMeans, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables in this study are presented in Table 2. Because we did not predict whether employee engagement and perceived social worth partially or fully mediate the effect of friendship on error disclosure, we tested two competing models: a fully mediated model (Model 1) and a partially mediated model (Model 2). Model 2 differed from Model 1 in a direct path from friendship to error disclosure. The results indicated that Model 2 (X2[114]=238.16; X2/df=2.09; GFI=.91; CFI=.94; NFI=.90; IFI=.94; RMSEA=.06) had a better fit, ΔX2[1]=37.93, p<.01, than Model 1 (X2[115]=276.09; X2/df=2.4; GFI=.89; CFI=.93; NFI=.88; IFI=.93; RMSEA=.07). Accordingly, we retained Model 2, the partially mediated model, as the preferable model.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables.

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Friendship at work | 20.27 | 4.97 | |||||

| 2. Employee engagement | 19.89 | 2.90 | .49** | ||||

| 3. Perceived social worth | 11.86 | 1.78 | .44** | .51** | |||

| 4. Error disclosure | 10.93 | 2.44 | .62** | .52** | .48** | ||

| 5. Supportive organizational context | 18.48 | 2.61 | .17** | .36** | .43** | .24** | |

| 6. Psychological safety | 13.11 | 3.28 | .17** | .18** | .19** | .33** | .14* |

In addition, after controlling the effects of supportive organizational context and psychological safety, the direction and significance tests of all paths in Model 2 were unchanged. However, Model 2 without control variables had a better fit, ΔX2[178]=422.58, p<.01, than Model 2 with control variables included, which did not fit the data as well (X2[292]=660.74; X2/df=2.26; GFI=.84; CFI=.89; NFI=.82; IFI=.89; RMSEA=.07). Because the results were unchanged between Model 2 without and with control variables, for model parsimony and simplicity, we presented Model 2, the partially mediated model, without control variables included and used it to examine the proposed hypotheses.

As shown in Fig. 1, all standardized path coefficients were statistically significant and in the predicted directions. The standardized path coefficients from friendship to error disclosure, employee engagement, and perceived social worth and from the latter two variables to error disclosure were 0.50 (p<0.01), 0.61 (p<0.01), 0.57 (p<0.01), 0.20 (p<0.05), and 0.21 (p<0.01), respectively. These paths accounted for approximately 60% of the observed variance in error disclosure. The total, direct, and indirect effects of friendship on error disclosure had the statistically significant coefficients of 0.74 (p<0.05), 0.50 (p<0.05), and 0.24 (p<0.05), respectively. Accordingly, the empirical results offered support for Hypotheses (Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2, and Hypothesis 3), i.e., friendship in the work-unit had a positive relationship with error disclosure, and this relationship was partially mediated by employee engagement and perceived social worth in the work-unit.

DiscussionThis study examines and empirically supports the facilitating effect of employee friendship on error disclosure and the processes by which employee engagement and perceived social worth mediate the relationship studied. Our findings have several theoretical implications. First, the results of this study indicate that individual differences in the relational aspect can complement the stances in error disclosure research, in which organizational efforts and contextual bearings are much identified and individual influence receives scarce attention (Zhao and Olivera, 2006). Extant literature highlights the social cost of error and posits error disclosure as a response to situations of reduced cost (Dyck et al., 2005; Gold et al., 2014; Uribe et al., 2002). Alternatively, we adopt COR theory and provide a perspective that elucidates the beneficial nature of error (i.e., job knowledge learning and routine-breaking stimulation), treats error as a job resource that employees essentially desire to possess exclusively, and posits error disclosure as a form of resource-sharing. Although the literature may provide an explanation for error disclosure, this study captures the nature of error cognition and the processes of error disclosure, thus contributing to the error literature.

Second, while the error literature focuses on contextual factors, which are managed by organizations and extrinsically motivate error disclosure, this study contributes by examining individual motivation from friendship, which is underlain by the intrinsic desire for friendship favoritism of us. Extrinsic motivation secures only temporary compliance, whereas intrinsic motivation – the desire to exert effort without organizational (i.e., extrinsic) interventions – has a longer-lasting effect and is more effective in motivating superior effort (Lin, 2007; Hackman and Oldham, 1976). Error research can identify more intrinsic motivators (e.g., value congruence, job significance, work meaningfulness, self-evaluation; Grant, 2008; Judge and Hurst, 2007; Rich et al., 2010) of error disclosure.

Third, literature has proposed rational choice for error disclosure. For example, if the recipient can help mitigating the negative consequences or solving related problems caused by the error, or the chance that the error will be detected by others/system is high, error disclosure is more likely (Rybowiak et al., 1999; Uribe et al., 2002). Notably, rational choice for error disclosure is self-directed; i.e., it yields benefit for error makers themselves. This study proposes a relational approach as an alternative perspective on error disclosure; i.e., friendship for error disclosure is other-directed to share the job resources of error with and yield benefit for coworkers. Error disclosure is discretionary (Zhao and Olivera, 2006) and literature indicates that discretionary behaviors at work can be either self-directed or other-directed (Van Dyne et al., 2003). Thus, the self-directed and other-directed perspectives on error disclosure are complementary with each other to enrich the error literature and facilitate organizational encouragement of error disclosure.

Forth, friendship has been linked to desirable and undesirable outcomes and to personal and organizational outcomes (Dotan, 2009; Methot et al., 2016; Morrison and Wright, 2009). This study provides evidence that error disclosure should be added to the positive correlates of friendship. Further, this study extends the workplace friendship literature by addressing the underlying processes by which friendship manifests itself in individual outcomes. Such mediating processes and mechanisms are indicated to have been scarcely identified and should be a desirable next step for advancing the literature on workplace friendship (Dotan, 2009; Methot et al., 2016). Additionally, that literature has much used social exchange theory (Methot et al., 2016; Morrison and Wright, 2009), whereas this study uses COR theory as its underlying explanation. Expanding the theoretical lenses may facilitate our understanding of the psychological processes underlying the influence of friendship at work.

This study offers differentiated insights into employee voice, which is intended to improve organizational functioning and is influenced by relationships at work (e.g., LePine and Van Dyne, 1998; Pauksztat, 2011; Zhang et al., 2015). These influences refer to work relationships and are explained with psychological safety, reciprocity and interactional quality. Further, the voice content in previous studies concerned organizational problems and issues, unrelating to voice speakers’ own job resources, and did not involve voice speakers’ own errors at work. This study opens up a new line accentuating the personal aspects of relationships at work and presents differentiated explanations with personal friendship favoritism of us and with the voice content that is both a resource gain and a resource loss for voice speakers. These explanations seem to be underused in employee voice research and can provide a new perspective.

Finally, because error disclosure is discretionary, benefits and is needed by the organization (as noted earlier), it is a form of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). The results of this study seem to be inconsistent with previous findings (Zagenczyk et al., 2008) that friendship at work does not enhance OCB. Notably, previous findings have shown that OCB depletes employees’ resources (e.g., time, attention, physical and emotional energy) and does not gain employees resources, whereas error is a resource gain and error disclosure is a form of resource sharing with coworkers. In other words, whether the content of OCB benefits the actors themselves, i.e., as a resource, should be assessed in OCB research, which has much assessed the intended beneficiary of the behavior (i.e., individual- vs. organization-targeted OCBs; Organ, 1997).

As indicated above, error disclosure can be self-directed (e.g., rational choice) or other-directed (e.g., friendship) and there is the possibility that self-directed situations, which can come from organizational and task-related context conditions, influence the extent to which friendship will be salient to error disclosure. For example, when an error maker can not find the reason why he/she makes the error or the error consequences on others and/or his/her work are more severe, the positive effect of friendship on error disclosure may be enhanced because the error maker may more desire to share error with friends and to enhance their job knowledge learning and routine-breaking simulation from error to gain their help with the error reason-finding or with error prevention intervention. There are also the probabilities that the error is detected by others/system or that the error maker's career is affected. If those possibilities are high, friendship may more enforce error disclosure to gain friends’ support at work. Further, when the error maker's frequency of previous errors is high or the error-admitting climate in the workplace is low, the image loss may be aggravated and thus friendship may less enforce error disclosure. Together, future studies would gain leverage to explicate the role of those organizational and task-related context conditions on the friendship-error disclosure relationship and to strengthen the understanding of the nature of that relationship.

Managerial implicationsOur findings are more significant today because an increase in employee errors has emerged since organizational change has been increasingly used to manage the challenges of today's hypercompetitive and continuously changing environment (Goodman and Ramanujam, 2012) and because employees are increasingly calling for higher relationship quality at work, which involves the development of friendships mainly within their work-units/teams (Tse et al., 2008). Because friendship enhances error disclosure, it facilitates organizational change and team effectiveness by decreasing the concealment of work errors. We suggest that organizations embed friendship development in job design by, for example, collaborative work, team-based rewards, and coworker references or feedback.

Organizations have long relied on contextual promotion of error disclosure (as noted earlier). This study suggests relational promotion by friendship. Organizations can use both contextual and relational approaches to enhance error disclosure. However, these may be incongruent. We propose the following implications.

Organizations contextually motivate employees to disclose others’ errors (Gold et al., 2014) using the whistle blowing approach. However, this will harm relationships at work and eventually hinder error disclosure, teamwork and firms’ performance. We argue that whistle-blowing is not a suitable approach to disclosing others’ errors; instead, it should be used to disclose the misconduct and fraud of organizational policies and regulations. Misconduct and fraud are intentional and are used to further inappropriate or unlawful interests (Kang, 2008); they should not happen at all, while errors are unintended deviations and cannot be entirely avoided (Hofmann and Frese, 2011).

Another contextual approach is to reward error disclosers (e.g., Sexton et al., 2000; Uribe et al., 2002). Yet, such an individual-based reward may decrease employee disclosure to coworkers in order to exclusively obtain the reward. Understandably, exclusiveness, i.e., not sharing, will damage relationships among team members and will disadvantage teamwork and the organization. We propose that organizations encourage friendship (for example, by embedding it in job design) to promote error disclosure and that the reward for error disclosure should be team-based. This would utilize and reinforce friendship among team members, forming a positive spiral between error disclosure and friendship development. In sum, managerial approaches to contextually promoting error disclosure should be vigilant about their incongruence with (i.e., their hindrance to) the relational approach by friendship so as to have a conjoint effect for organizational and team effectiveness.

Limitations and future researchThe limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, this is a study of perceptions. As attitudes and perceptions are important antecedents of behavior (Frenkel and Sanders, 2007), further research can measure employee behavior to verify the findings of this study. In addition, this study is positioned at the individual level and is to examine individual perceptions at work. Specifically, this study is to understand an individual employee's perception of friendship within his/her team/work-unit and his/her error disclosure within the team/work-unit. These are individual perceptions in a group and the friendship and error disclosure in this study are individual-level variables. This approach is underlined by the research on employee relationships at work, which involves individual employees’ perceptions of workplace friendship within their work-unit (Tse et al., 2008). Besides, this study measured friendship and error disclosure as general psychometric attributes. Future study can use a sociometric research design to measure who discloses what to whom in an employee's team/work-unit (e.g., error disclosure may only to (a) certain friend(s) and not to more other friends, thus maintaining resources from friendships) to strengthen the understanding of the nature of the friendship-error disclosure relationship.

Second, while error disclosure is affected by friendship, it may itself affect friendship. Frequent interactions about error knowledge and routine-breaking may facilitate friendship development. Yet, the co-evolution of friendship and error disclosure cannot be traced in the data of this study, and the purpose of this study is to identity an individual, relational factor of error disclosure to contribute to the error literature. Third, the Taiwanese context of this study suggests that further testing using samples from other countries or cultures would provide a more robust test of the hypotheses because cultural differences influence employee perceptions at work. Taiwanese tend to have the Chinese cultural value of collectivism (Meindl et al., 1989; Wong et al., 2010), and they “see themselves as parts of one or more collectives (family, co-workers, tribe, nation); are primarily motivated by the norms of … those collectives; …” (Triandis, 1995, p.2). Taiwanese employees would hence be more reluctant to be known as error makers who act contrary to what workplace norms tell them to do (including to do things correctly). This would tend to weaken the relationship between friendship at work and error disclosure. In other words, the Taiwanese context may decrease, rather than increase, effect sizes. It is thus unlikely that cultural influence in Taiwan compromised the validity of the results.

Finally, managerial levels endeavor to elevate error disclosure, and this elicits curiosity about managerial jobs. Managers need to motivate and develop employees (Nohria et al., 2008) and may be more willing to share the benefits of their own errors, thus reinforcing friendship's effect on error disclosure. However, managerial jobs have a distinctive stance compared with non-managerial jobs and have relatively a low standard model (Longenecker, 1997), meaning that the benefits of managerial errors may be viewed as neither useable nor understandable to others, hence attenuating the friendship effect studied. These inconsistent arguments for the moderating role of managerial positions need an answer from future study. Error research seems to focus on employees and has scarcely examined the perspective of managerial/non-managerial positions, noting that an organizational structure perspective (e.g., working position, unit/team size, collaboration type) is also scarce. These scarcities merit further research by the error literature, which could improve error management in organizations.

Construct items

In the following questions, coworkers refer to those in your work-unit.

Friendship at work

- 1.

I have formed strong friendships at work.

- 2.

I socialize with coworkers outside of the workplace.

- 3.

I can confide in people at work.

- 4.

I feel I can trust many coworkers a great deal.

- 5.

Being able to see coworkers is one reason why I look forward to my job.

- 6.

I do not feel that anyone I work with is a true friend. (reverse-coded)

Error disclosure

- 1.

When I make an error at work, I tell coworkers.

- 2.

I would rather keep my errors at work to myself. (reverse-coded)

- 3.

I do not think it useful to talk about my errors at work. (reverse-coded)

Perceived social worth

- 1.

I feel coworkers appreciate my work.

- 2.

I feel coworkers value my contribution at work.

- 3.

I do not feel coworkers appreciate my effort for them. (reverse-coded)

Employee engagement

- 1.

One of the most interesting things for me is getting involved with the things happening in this work-unit.

- 2.

I am really not into the “goings-on” in this work-unit. (reverse-coded)

- 3.

Being a member of this work-unit makes me come “alive”.

- 4.

Being a member of this work-unit is exhilarating for me.

- 5.

I am highly engaged in this work-unit.

Supportive organizational context

- 1.

I get all the information I need to do my work and plan my schedule.

- 2.

It is easy for me to obtain expert assistance when something comes up that I do not know how to handle.

- 3.

I am kept in the dark about current developments and future plans that may affect my work. (reverse-coded)

- 4.

I lack access to useful training on the job. (reverse-coded)

- 5.

Excellent work pays off in this company.

Psychological safety

- 1.

If I make an error, it is often held against me. (reverse-coded)

- 2.

I am able to bring up problems and tough issues.

- 3.

It is safe to take a risk in my organization.

- 4.

It is difficult to ask other members for help. (reverse-coded)

Discriminant validity

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Friendship at work | .82 | |||||

| 2. Employee engagement | .24 | .68 | ||||

| 3. Perceived social worth | .19 | .26 | .64 | |||

| 4. Error disclosure | .38 | .27 | .23 | .75 | ||

| 5. Supportive organizational context | .03 | .13 | .18 | .06 | .78 | |

| 6. Psychological safety | .03 | .03 | .04 | .11 | .02 | .72 |

Note: Diagonals display the average variance extracted, while the other matrix entries display the squared correlations.

Workplace romance is also a type of workplace relationship, but it is a very special type of interpersonal relationship (Bridge and Baxter, 1992) that this study does not address. That is, workplace romance is beyond the scope of this study.