Literature on brand deletion (BD), a critical and topical decision within a firm's marketing strategy, is extremely scarce. The present research is concerned with the decision-making process and examines the effect on BD success of three different approaches to decision-making – rational, intuitive and political – and of the interaction between the rational and political approaches. The moderating effect of the type of BD – i.e., total brand killing or disposal vs. brand name change – is also analyzed. The model is tested on a sample of 155 cases of BD. Results point to positive effects on BD success of both rationality and intuition, and a negative effect of politics. Findings also indicate that the negative impact of political behavior on BD success is minimized in the absence of evidence and objective information and when the BD is undertaken through a brand name change.

After decades in which building a diversified portfolio of brands coupled with deep product lines was a customary practice in many firms (Keller et al., 2011; Morgan and Rego, 2009; Rosenbaum-Elliott et al., 2015), with the turnaround of the century we have witnessed a reversal in this trend. Thus, brand deletion (hereinafter BD), i.e., discontinuing a brand from a firm's brand portfolio (Shah, 2013), in their different types, emerges as a strategic decision in the realm of brand portfolio management. Brands can be deleted through a brand name change. Examples of this move are the migration by Unilever from Starlux to Knorr, or the rebranding by the Santander banking group from Abbey in the UK or Banesto in Spain to the global brand Santander. In other instances, the deletion occurs through a total brand killing, so the company retires from the market both the brand and the product lines commercialized under that brand, as did General Motors (GM) when eliminating some emblematic brands, such as Hummer, Pontiac or Saturn. In the cases of Saab, Opel or Vauxhall, the deletion was made through brand disposals, as these brands were sold by GM and the new owners assumed their commercial use. Disposal was also used by the Danone Corporation to delete brands such as San Miguel, in the beer market (Barrett, 2000), or Lu and Príncipe, in the biscuits market (Jones, 2007).

These examples are not exceptional and serve to illustrate how more and more companies from diverse manufacturing and service sectors are embarking on BD strategies. Three main world-wide environmental factors have impelled BD and led many firms to focus on competing more strongly through their most strategically important brands. Firstly, days of rapid growth drew to a close for many industries and companies, and efficiency became a priority (Hooley and Saunders, 1993), which forced many diversified corporations to get rid of businesses that were unrelated to their own core competences (Varadarajan et al., 2006). Secondly, market globalization facilitated significant cost reductions derived from outsourcing and relocating operations in emerging countries, but it also triggered substantially increased market competition. The reaction of many corporations has been to focus their efforts on fewer but stronger brands with a global presence, divesting from local or regional brands (Depecik et al., 2014; Özsomer et al., 2012). Thirdly, the rising market share of private label brands has further prompted manufacturers to compete with a smaller set of strong brands rather than with a larger set of weak ones, thus deleting underperforming and secondary national brands (Sloot and Verhoef, 2008).

However, despite the strategic nature of the BD decision and the fact that many companies are suffering the environmental circumstances mentioned above, managers are not knowledgeable about how they should tackle the challenge to delete a brand, and scholarly research on BD is so scarce and fragmented that it is hard to talk of a cohesive body of knowledge on the subject.

Very few researchers have conceptually or empirically addressed issues of BD. Table 1 summarizes the main contributions found in this emerging but relevant research area. As regards conceptual works, Kumar (2003) adopts a normative approach and outlines a set of recommendations guiding managers during the BD process. The other conceptual works are geared toward classifying the explanatory factors underlying the BD adoption propensity either in general (Shah, 2015; Varadarajan et al., 2006) or in multinationals (Ketkar and Podoshen, 2015). Shah (2017a) identifies the outcomes which could serve to define a BD as successful and suggests a set of decision and implementation factors which could have an impact on these outcomes. Empirical papers are also scant and tend to focus on the outcomes of BD, either considering consumer evaluations as a performance measure (Mao et al., 2009; Mishra, 2017) or analyzing the impact on the firm's value by looking at stock market reactions after the announcement of a brand disposal (Depecik et al., 2014; Wiles et al., 2012). These studies reveal factors which affect customer and investors reactions to a BD (e.g., type of BD, brand weakness, scope, relatedness to other brands in the portfolio), yet treat BD as an exogenous event. In other words, these studies do not explicitly consider the BD decision maker's point of view and fail to examine why or how a BD decision was taken and how it was implemented. One notable exception is the qualitative research by Shah (2017b) and Shah et al. (2017) in which, based on grounded theory, a causal model of the BD strategy is proposed and several questions are explored such as the context, reasons and fit of this strategy, the types of BD, as well as its implementation and consequences. Even if we look at a related field of study, namely research into brand delistings – i.e., the retailer's decision to remove an entire brand from its assortment, leading to the unavailability of the deleted brand within the retailer's stores, we see how this has been neglected in the literature, with empirical research having opted to focus on customer reaction to the delisting (Sloot and Verhoef, 2008; Wiebach and Hildebrandt, 2012).

Summary of BD research.

| Conceptual studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Variables seta | Main conclusions | |

| Kumar (2003) | To guide managers when facing the decision on BD. | B | This author recommends how to put into practice a brand portfolio rationalization program in order to release and reallocate resources in stronger brands. |

| Varadarajan et al. (2006) | To develop a conceptual model delineating the drivers of BD propensity. | A | These authors discuss how BD enables a firm to free up resources which may be redeployed to enhance the competitive standing and financial performance of other brands in its portfolio. They propose a theoretical model of the organizational and environmental drivers of BD propensity and suggest several moderating factors. |

| Shah (2015) | To theoretically explain the factors influencing a firm's decision to retain or discard a brand. | A,B,C | She outlines a theoretical model in which new relationships among established constructs in the strategic decision-making and brand management literature are proposed. Specifically, it explains how internal, external and top management factors influence the decision to retain or discard a weak brand. |

| Ketkar and Podoshen (2015) | To propose a theoretical framework of the brand disposal and brand exit strategies among multinational firms. | A | A new theoretical framework is introduced to explain BD and brand exit strategies among multinational firms. Their research categorizes BD strategies according to the relatedness of underlying brand capabilities and the entry mode of the brand. |

| Shah (2017a) | To present a list of success factors and outcomes of BD. | B,C,D | The success of a BD depends on factors related to the brand, to the deletion process, and to the stakeholders influenced by or influencing the decision. As BD outcomes, she considers the impact on customer relationships, as well as on the firm's competitive position and financial performance. |

| Empirical studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Variables set | Sample/methodology | Main findings | |

| Sloot and Verhoef (2008) Quantitative | To examine customer responses to a brand delisting by a retailer. | D | Beer buyers and supermarket consumers/controlled experimental design. | Consumer choices are affected by brand delistings, and the switching patterns provoked by this strategy tend to cause bigger losses for manufacturers than for retailers. |

| Mao et al. (2009) Quantitative | To examine how brand elimination might influence consumer evaluations of the firm. | D | University students/structural equation modeling (SEM). | Explanations provided by the firm and loyal customers on weak brands eliminated are more likely to be associated with eliminate-to-improve attributions. |

| Wiebach and Hildebrandt (2012) Quantitative | To examine consumers’ reactions in terms of store and brand switching when a retailer delists a brand. | D | University students/real live experiment. | The retailers’ strategy of brand delisting as a means to enhance their negotiation power and to reduce their dependence on national brands may be harmful as many consumers tend to stay brand loyal. |

| Wiles et al. (2012) Quantitative | To examine stock market reactions to brand acquisition and disposal announcements. | D | Secondary data of firms in USA (1994–2008)/event study analysis. | Returns of brand acquisitions and disposals depend on the firm's marketing capabilities, channel relationships and brand portfolio. Greater returns arise when the seller has inferior channel relationships, competes with multiple brands, and for the disposal of non-related brands or low price/quality brands. |

| Depecik et al. (2014) Quantitative | To examine the effect of brand divestments on firm value. | A | Brand portfolio rationalization announcements/event study analysis. | Brand divestments destroy firm value, except when divesting local or regional brands in non-core businesses. |

| Mishra (2017) Quantitative | To explore the consequences of brand deletion. | C,D | MBA students/controlled experimental design. | Evaluations of organizational performance depend on the strenght of the deleted brand, whether the brand is merged, sold or eliminated, and whether the firm communicates the logic of the deletion. |

| Shah (2017b) Qualitative | To explore the causes of BD in firms with a ‘house of brands’ portfolio. | A | Managers and archival data/grounded theory. | Brands are deleted because of financial factors, as well as because non-financial factors related to the consumers’ needs and preferences, the brand portfolio strategy and the firm's overall strategic direction and goals. |

| Shah et al. (2017) Qualitative | To understand the phenomenon of BD. | B | Managers and archival data/grounded theory. | Strong brands are a source of competitive advantage, but weak brands diminish the firm's competitive advantage. Deleting weak brands releases resources that can be reallocated to the strong brands to boost performance. |

Given the scarce and fragmented literature addressing BD and the importance of such a strategic decision vis-à-vis gaining or sustaining competitive advantage, further academic research exploring the factors which drive the success of BDs is clearly a must. The “black box” of how BDs are decided and executed must be opened. The present research is primarily concerned with the decision-making process. Based on the strategic decision-making literature (Child et al., 2010; Elbanna, 2006; Kester, 2011), we propose a model in which we consider how three different approaches to decision-making – namely, rational, intuitive and political – are related to BD success. We define BD success as the extent to which the company is satisfied with the outcomes and has achieved the objectives established at the time the decision was made. The use of these decision-making approaches have already been object of research in the strategic management literature, but the specificities of the BD strategy makes relevant to scrutinize their effect on performance in this particular context. Deleting a brand is usually a controversial and emotionally charged process (Shah, 2017a). Divergent perceptions, opinions and feelings are likely to emerge during the process. Whilst the BD may be considered indispensable for some stakeholders, for others it represents a failure or an unnecessary breach in the company's history. The extent to which rationality, intuition and politics drive (or are absent from) the decision-making can seriously affect the results from the deletion. Thus, our first objective is to empirically investigate how the way in which the BD is decided impacts on the outcomes of this decision. In addition, as outlined above, deleting a brand from a firm's portfolio may be carried out in a number of different ways (i.e., killing the brand, selling it, changing the brand name), each of which entails differing benefits and risks and which may require particular approaches. Based on a contingent perspective of the decision process-performance linkage (Fredrickson, 1983; Miller and Friesen, 1983), the second objective in this research is to investigate the interaction between the diverse approaches to decision-making and the type of BD to be executed. Therefore, we examine whether the influence of these approaches on BD success varies depending on whether the brand is totally killed off or sold to another company or deleted through a brand name change.

This research contributes to the strategic marketing and brand portfolio management literatures by addressing a managerially relevant and topical problem, namely, pruning a firm's brand portfolio, but which has thus far received little scholarly attention. We expand on the scant empirical research conducted to date into the results of BD and contribute to a better understanding of which factors under managerial control may render a BD more successful. More specifically, we delve more deeply into the BD decision-making process and analyze main and interactive effects of rational, intuitive and political approaches, which, alone or in combination, affect BD success. Furthermore, unlike prior quantitative research, which gathers experimental data from consumers concerning their reactions to fictitious BDs (Mao et al., 2009; Sloot and Verhoef, 2008; Wiebach and Hildebrandt, 2012) or which relies on secondary data and press reports (Depecik et al., 2014; Wiles et al., 2012), we have gathered information from managers about 155 real cases of recent BDs by companies in a range of different industries. Albeit in retrospect, this method did enable us to ascertain managers’ perceptions about the particular internal and external circumstances of each case of BD in our sample when the decision was made and implemented together with their evaluation of how appropriate each decision proved to be.

Theoretical frameworkThe BD decision can be considered as a critical strategic choice because, in addition to being infrequent, non-routine and complex, it involves an important relocation of a firm's resources, alters its brand architecture, seriously affects diverse stakeholders, and can have a major impact on long-term market and financial performance (Shah, 2015). In any case, this kind of decision must not be conceived as a stand-alone one-shot decision problem with a single optimal solution, but as a strategic decision-making process which different firms may approach in different ways.

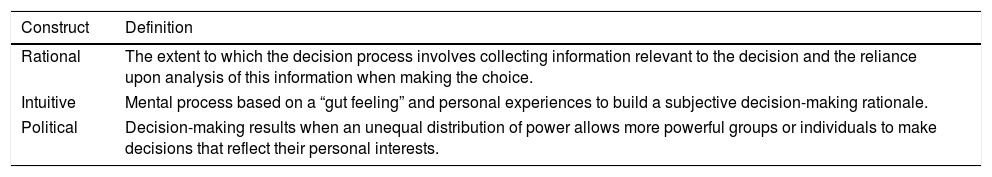

According to the strategic decision-making literature (Child et al., 2010; Elbanna, 2006; Kester, 2011), three dominant currents prevail: synoptic formalism, the incremental perspective and logical incrementalism. Synoptic formalism emphasizes deliberate, effortful and analytical procedures such as formal planning activities, generating alternatives and evaluating quantitative data as well as all relevant information as a basis for decision-making in order to reach an optimal decision (Atuahene-Gima and Li, 2004; Wiltbank et al., 2006). Rationality is the representative trait of the synoptic model (Elbanna and Child, 2007a). On the other hand, the incremental perspective advocates strategic decision-making based on adaptation through a gradual and complex process of learning, which is intuitive in nature (Atuahene-Gima and Li, 2004; Fredrickson, 1984; Rajagopalan and Spreitzer, 1997). Finally, Quinn (1980) proposes the logical incrementalism as an approach that combines elements of rational planning and intuitive behavior, and incorporates a third component: political maneuvering based on power and social interactions. As a group, people may differ in preferences and interests regarding the decisions to be taken within the company (Quinn, 1980). In this common scenario, politics may have a major influence on the strategic planning process and its outcomes (Eisenhardt and Zbaracki, 1992). In sum, logical incrementalism states that decisions are undertaken based on rationality, intuition and politics. Thus, following the literature (e.g., Elbanna and Child, 2007b; Kester, 2011) three approaches may be at work in the strategic decision-making process: rational, intuitive and political (see Table 2).

Approaches to the strategic decision-making process.

| Construct | Definition |

|---|---|

| Rational | The extent to which the decision process involves collecting information relevant to the decision and the reliance upon analysis of this information when making the choice. |

| Intuitive | Mental process based on a “gut feeling” and personal experiences to build a subjective decision-making rationale. |

| Political | Decision-making results when an unequal distribution of power allows more powerful groups or individuals to make decisions that reflect their personal interests. |

Rational decision-making is an approach characterized by an attempt to exhaustively gather the information relevant to the decision, and the reliance upon analysis of this information when making the choice (Dean and Sharfman, 1996). Intuitive decision-making refers to more incremental adaptations based on an intimate understanding of the situation (Eisenhardt and Zbaracki, 1992). It is a process based on experience, but is not necessarily biased and irrational, even if it may be difficult to articulate the reasons underlying the decisions taken when following this approach (Khatri and Ng, 2000). Therefore, although it is sometimes contaminated with presumptions and naïve preferences, intuition does represent a complex psychological phenomenon which helps in problem-solving by drawing from the store of knowledge in our subconscious and is rooted in past experience. In a political approach, the key assumption is that organizations are coalitions of people with competing interests. People with conflicting preferences may employ political tactics so as to shape decisions in line with their preferences. Consequently, we define political behavior as intentional attempts to enhance or protect the self-interest of individuals or groups (Hickson et al., 1986).

The literature has acknowledged that just one approach may not be sufficient to describe the complexity of the strategic decision-making process (Brews and Hunt, 1999; Eisenhardt and Zbaracki, 1992). As Hart and Banbury (1994) argue, strategic decision-making requires integrating both formal planning and incremental adjustments. Nutt (2002) contends that strategic decisions are made through the combined use of rational processes, judgment (intuition) and bargaining (politics). Our proposal is that rational, intuitive and political approaches to decision-making can coexist in a decision process, thus making it relevant to examine the specific impact each approach has on BD success, and even the interactive effects between them. Hence, as a first objective, hypotheses H1 to H4 of our research elaborate on how the different approaches to BD decision-making influence BD success (see Fig. 1).

As indicated in the introduction section, deleting a brand may come in a number of different forms: total brand killing (i.e., both the brand and the product lines commercialized under that brand are retired from the market), brand disposal (i.e., the brand disappears from the firm's portfolio but still remains on the market because it is sold to another company that assumes its ownership and commercial use), and brand name change (i.e., the brand is eliminated in order to sell the same – or very similar – products or services under another brand name or trademark of the same or from a different company). Both total killing and disposal entail determining an irreversible strategic decision since it usually involves the company getting out of the market and closing or at least downsizing one or more of its business units. Alternatively, when the BD is undertaken through a brand name change, the company reduces the number of brands in its portfolio currently used for commercial purposes, although it retains ownership of the deleted brand name and remains in the market. This form of BD is also strategic since it alters the company's brand architecture and its branding strategy, but compared to total killings or disposals, brand name changes are less risky as they can be reversed or implemented gradually. Given the unequal consequences and risk of the different BD types, we argue that this variable conditions how rational, intuitive and political approaches to the decision might impact on the success of the deletion. Therefore, a second objective in our study is to explore the moderating effect of the type of BD on the relationship between the different approaches to BD decision-making and BD success. This objective is specified in H5 to H7 (see Fig. 1).

Hypotheses developmentThe decision-making process and BD successRational decision-making is the process by which firms use objective information and empirical evidence to build decisions. There is considerable consensus concerning the positive effect of this kind of decision-making approach and performance. For example, in the subject of NPD portfolio decisions, Kester (2011) and Dean and Sharfman (1996) find a positive relationship between rational decision-making and portfolio decision-making effectiveness. Similarly, in the strategic planning research area, Miller and Cardinal (1994) and Schwenk and Shrader (1993) observe a positive relationship between planning and superior performance. When managers make the BD decision as a result of careful thought based on a comprehensive assessment of the economic, financial and market situation of the deleted brand, and after having exhaustively generated and evaluated numerous potential courses of action, the decision taken is most likely the best alternative. Moreover, during the rational and well-thought out decision-making process, potential problems and risks associated to the decision may be anticipated, thereby helping managers to have a clearer view of what solutions there are and, thus, proactively act upon them. Therefore, we hypothesize that,H1 The greater the rationality in BD decision-making, the greater the BD success.

The literature defines intuitive decision-making as an unconscious process involving holistic associations, although there is no agreement regarding whether intuition is derived from experience or from naïve preferences (Kester, 2011). A considerable amount of literature exists arguing the benefits of intuition in strategic decision-making (e.g., Akinci and Sadler-Smith, 2012; Dane and Pratt, 2007; Dayan and Elbanna, 2011; Khatri and Ng, 2000; Sadler-Smith and Shefy, 2004). In the context of BD decision-making, emotions and opinions will surely emerge during the process. Yet given its strategic nature, managers are unlikely to make such an important decision using merely naïve preferences. On the contrary, it is probable and maybe frequent that managers use, to some extent, holistic assumptions derived from prior experience in order to build a subjective decision-making rationale. When executives involved in a BD decision draw on the managerial experience forged from years of dealing with diverse, complex and important issues, such decisions will benefit from a deep knowledge of any and all relevant domains, thereby enabling them to select which factors they should focus on when seeking to make an accurate and effective decision. Managers’ experience should reinforce the credibility of their opinions, helping them to gain respect and also to deal with the stress and difficulties surrounding this decision. Therefore, following strategic decision-making literature, intuition-based decision-making is expected to prove natural and faster, and this approach leads to a more efficient management of BD. Accordingly, we propose that:H2 The greater the intuition in BD decision-making, the greater the BD success.

Political behaviors are characterized as those observable actions by which people use their power to influence a decision (Eisenhardt and Zbaracki, 1992). To date, researchers have acknowledged that political behavior is an undeniable part of how organizations operate, and how strategic decisions are made (Child and Tsai, 2005). Subsequently, several studies have explored the effects of political behavior on the outcomes of the strategic decision-making process. Based on such studies (Dean and Sharfman, 1996; Elbanna and Child, 2007b), we identify three causes for a negative relationship between political behavior and BD success. First, managers under this approach may tend to put their self-interest above the company's interest when deleting a brand. Consequently, this decision-making approach may prevent a full understanding of any environmental constraints since the decision is directed toward the interest of particular groups rather than what is desirable or feasible for the firm given the contextual limitations. Second, private interests may lead to distorted information being conveyed about the brand, thus resulting in decisions based on inadequate or incomplete information. Third, political processes may prove time-consuming which can lead to inefficiencies, delays in decision-making (Nutt, 2002) and lost opportunities (Pfeffer, 1992). Thus, we suggest that:H3 Political decision-making negatively influences BD success.

When adopting political criteria, strategic decisions are made in the interest of one or several groups within the company. Political behavior is generally considered detrimental to organizational performance, and this negative effect is likely to be exacerbated when the company has exhaustive information and when multiple alternatives have been analyzed. In this case, there is a growing awareness of the deviations from an optimal decision when the politics and self-interest of a dominant group shapes the decision. Use of incomplete or biased information, obstacles to information-searching, or biased disclosure of information, so typical of political behavior, may be hidden within the company when there is no evidence to support the decision or when it does not have access to valid information sources. But implementing a decision for which sufficient information was available and then became blurred by political maneuvering can compromise the quality of the decision and reduce cohesion and commitment. Consequently, we consider there is an interaction effect between rationality and politics in such a way that the negative impact of political behavior on BD success is more evident when the firm has made a comprehensive assessment of the situation based on objective information. In this sense, Dean and Sharfman (1993) found that a high level of rationality and a low level of politics are optimal for making a successful strategic decision. Therefore, we propose that:H4 There is a negative interaction between rational and political approaches to BD decision-making, such that the greater the rationality, the greater the negative effect of political decision-making on BD success.

Collecting as much information as possible in order to make a rational decision is a process that should involve examining the potential trade-offs of the value, effort and time required to gather additional evidence to reduce uncertainty and increase appropriateness of the decision made, in this case deleting a brand in the firm's portfolio (Atuahene-Gima and Li, 2004). Papadakis et al. (1998) state that decision-makers act more rationally when decisions imply important consequences.

Totally killing a brand or selling it to another company are examples of irreversible strategic moves which entail a go/no-go decision and require a strong determination before the decision is executed. Both types of BD may cause a major impact and will probably face the rejection by important stakeholders, such as the affected customers and channel partners, employees, managers or investors. Furthermore, a brand disposal means losing ownership of an asset which in the past may have yielded significant profits and prestige to the firm. In these instances, exhaustive data gathering and analysis should help ensure the BD strategy is right, otherwise the firm will likely perceive safer to retain the brand in its portfolio and discard the deletion. In other instances of BD, the value of having greater number of evidences may not compensate for the drawbacks of a delay in making and implementing the decision. This seems to be the case when a brand is deleted by changing its name, since the firm retains legal ownership of the brand and BD decision may be more easily reversed if expected results are not achieved. Accordingly, we suggest:H5 The positive effect of rational decision-making in BD success will be less positive when the firm is changing the brand name than when the firm is totally killing the brand or selling it to another company.

As argued previously, intuitive decision-making may also be beneficial if opinions and intuitive judgments are not derived from inexperience, naïve estimations and cognitive biases that lead to poor decisions, but rather from decision-makers’ experience and familiarity with the competitive arena (Shepherd and Rudd, 2012), enabling them to make fast, accurate and effective decisions (Kester, 2011).

Brand managers who are considering killing or disposing of a brand are less likely to have confronted such a critical decision and have a know-how that facilitates a rapid but precise assessment of the situation, the most viable strategic alternatives and the expected outcomes. In this case, flawed and unsound beliefs are likely to emerge if managers attempt to replace evidence with intuition, which may drive the BD to a failure. In contrast, brand name change is a quite common strategy (Pauwels-Delassus and Mogos-Descotes, 2012), and thus firms can rely on judgments based on their own experience or on the success or failure of other companies that made previous similar decisions. Furthermore, a natural and agile decision based on intuitions derived from managers’ domain of expertise may bring the conviction and determination required to make the BD successful. Therefore, we propose:H6 The positive effect of intuitive decision-making in BD success will be more positive when the firm is changing the brand name than when the firm is killing or selling the brand.

In H3, a negative effect of political decision-making on BD success was suggested. However, the use of political tactics such as negotiation and bargaining, or coalition formation may prove necessary and beneficial for creating change and adaptation, particularly in situations where the interests of particular groups are not necessarily irreconcilable. “Selling” adequately the issue and ensuring that all the aspects are fully debated should help to specify better solutions and lead to greater acceptance (Kester, 2011). When firms decide to change a brand name, it may be perceived as a threat by certain stakeholders who are directly involved with the deleted brand or more closely attached to it. In these cases, diplomacy and persuasion may help to gain support and overcome difficulties in getting the BD decision approved and implemented. In contrast, when a brand is killed or sold to another company, even when all the evidence leads to consider the decision to be undeniably good for the company, conflicts of interest will inevitably emerge and those stakeholders who feel the decision does not benefit them will likely fight it back. Compromising and trying to convince those groups most noticeably affected and “damaged” by the deletion will probably prove a waste of time. We thus hypothesize that:H7 The negative effect of political decision-making on BD success will be less negative when the firm is changing the brand name than when the firm is totally killing the brand or selling it to another company.

To test the hypotheses of our research model, data were gathered using a cross-sectional survey with Spanish firms. Since there is no comprehensive list of Spanish companies that have taken the decision to delete a brand, we searched using the Amadeus database for qualified companies with at least one brand registered in the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office (SPTO) and employing over 50 staff. In the effort to cover a broad range of both manufacturing and service industries, 4075 firms were identified. From this prior screening, approximately a third (i.e., 1362 firms) were randomly selected using stratified sampling with the industry as stratum. All the firms were contacted by telephone or email to inform them about our research and to request their participation in cases where at least one brand had recently been deleted from their company's brand portfolio. In this initial contact, 232 companies expressed their wish to participate. 792 firms were excluded because they had either not deleted any brand or because they belonged to a corporation where the parent company was already included in the sample. 338 refused to participate because, despite our guarantee of total confidentiality, they did not wish to disclose any information concerning this type of decision or because the managers were too busy to comply with our request.

As a means of exploring the manager's point of view regarding the relevance of the variables identified in our literature review on BD decision-making, we conducted eight in-depth interviews with executives, five of whom worked in firms operating in service industries, and the other three in the manufacturing industry. As regards size, three of the interviewees were top managers in medium-sized companies and five in large companies. These interviews also served to refine and pre-test the questionnaire designed to gather data for the empirical analysis.

The final version of the questionnaire, in which the unit of analysis is a case of BD recently carried out by the respondent firm, was sent to the 232 companies that agreed to participate, along with two letters of support by Interbrand and the Leading Brands of Spain Forum and a letter thanking them for participating in our research, and explaining the benefits of joining our research in terms of full access to the research findings. After a follow-up by telephone and personal visits to their offices, we obtained 155 complete questionnaires, provided by 111 respondent firms, yielding an effective response rate of 48%. Table 3 shows the sample characteristics. Respondents were asked about their direct participation in the BD decision and implementation as well as their knowledge of the reasons and facts surrounding the deletion. Mean scores for these questions were, respectively, 5.75 and 6.38 out of 7, indicating that the key informants in our sample are a valid source of information.

Sample characteristics.

| Brand characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Type of BD | N | % | |

| Deleted brand | |||||

| Created | 108 | 69.70% | Total brand killing or disposal | 71 | 45.80% |

| Acquired | 47 | 30.30% | Brand name change | 84 | 54.20% |

| Total | 155 | 100.00% | Total | 155 | 100.00% |

| Geographical scope | |||||

| Local/regional | 23 | 14.80% | |||

| National | 95 | 61.30% | |||

| International | 37 | 23.90% | |||

| Total | 155 | 100% | |||

| Firm characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | N | % | Family business | N | % |

| Manufacturing | 39 | 35.10% | Yes | 75 | 67.60% |

| Service | 72 | 64.90% | No | 36 | 32.40% |

| Total | 111 | 100.00% | Total | 111 | 100.00% |

| Firm characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of employees (2014) | N | % | Turnover (2014) | N | % |

| <50 | 5 | 3.60% | ≤10 | 6 | 2.70% |

| <250 | 32 | 28.83% | ≤50 | 26 | 23.42% |

| >251 | 71 | 63.96% | >50 | 67 | 60.36% |

| N.A. | 3 | 2.70% | N.A. | 12 | 10.81% |

| Total | 111 | 100.00% | Total | 111 | 100.00% |

| Firm characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Market targeted | % |

| Consumer | 55.70% |

| Industrial | 44.30% |

| Total | 100.00% |

Sample representativeness was assessed as follows. We conducted a proportion test among the companies in the sample and in the population using the industry as the strata variable. The results in Table 4 show that the wholesale and retail trade sector is significantly underrepresented in the sample, while the information and communication sector is significantly overrepresented. The reason might be the inclusion of a large number of wholesalers in the “Wholesale and retail trade” group (NACE code 45, 46 and 47). For these companies, the strategy of using the brand as an asset on which to base the value proposition is of little importance when compared to other industries. It is uncommon for wholesalers to own several brands (they sometimes own only one) and, when they do own them, they are used primarily for identification purposes rather than for differentiation. The decision to eliminate a brand rarely occurs, hence the low representation of this industry in the sample. In contrast, in the information and communication sector, knowing that Atresmedia, one of the leading private media groups in Spain, was taking part in our research had a snowball effect, encouraging other companies within this sector to also participate.

Population and sample distribution by industry: proportion test.

| NACE code | Population | Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % of total | N | % of total | |

| 10,11,12,13,14,15. Manufacture of food, tobacco and wearing apparel. | 82 | 14.39% | 19 | 17.12% |

| 20,21,22,23,24,25. Manufacture of chemical, pharmaceutical, plastic and metal products. | 68 | 11.93% | 12 | 10.81% |

| 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Manufacture of electronic and optical products and machinery and furniture. | 23 | 4.04% | 5 | 4.50% |

| 35,36,38,41 Electricity supply, water collection and waste management. | 6 | 1.05% | 2 | 1.80% |

| 45,46,47. Wholesale and retail trade. | 190 | 33.33%* | 24 | 21.62%* |

| 49,52,53,55,56. Transportation, storage and housing services. | 18 | 3.16% | 3 | 2.70% |

| 58,59,60,61,62,63. Information and communication. | 19 | 3.33%* | 12 | 10.81%* |

| 64,65,66,69,70. Financial, insurance and professional activities. | 129 | 22.63% | 24 | 21.62% |

| 71,73,74,77,79,81,82,85,86. Scientific, technical support education and health activities. | 35 | 6.14% | 10 | 9.01% |

| Total | 570 | 100% | 111 | 100% |

To assess the quality of the gathered data, we compared the correlation between the data on sales and employees extracted from the Amadeus database, and the data on sales and employees reported by respondents. The correlation for sales is .89, and the correlation for employees is .88, providing an indication of the reliability of the answers given by informants. In addition, following the recommendation of Armstrong and Overton (1977), we examined the potential influence of non-response bias by comparing early (33%) and late respondents (33%) via a t-test. No significant differences at p<.05 were found between the two groups regarding the constructs examined in this study.

Since a single informant provided the data for each BD case, we also examined whether common method bias (CMB) could be an issue in our survey. We attempted to a priori minimize method bias by using some of the best practices described in the literature (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Rindfleisch et al., 2008). In particular, we protected respondent anonymity and, as indicated above, ensured respondents were executives in a position to provide accurate information and opinions. In addition, item wording was carefully revised to prevent biased connotations, the dependent and independent variables were in separate parts of the questionnaire, and different scale formats were used (see Table 5). As post hoc analysis, we used Harman's one-factor test and results indicate that little common method variance (CMV) is observed in our data. According to Fuller et al. (2016), it is very unlikely that such a small CMV could substantially bias the estimated relationships. The observation of positive and negative construct intercorrelations (see Table 6) further supports the conclusion that the possible impact of CMB is minimal.

Construct measurement.

| Construct (Scale adapted of …) | Items | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Rational decision-makinga (Papadakis et al., 1998; Kester, 2011) | The management team made a comprehensive assessment of the economic, financial and market situation of the deleted brand. | 5.16 (1.80) |

| The decision was made in a systematic way (sequential, organized, logic and analytical). | 5.42 (1.65) | |

| The decision was based on evidence and objective information. | 5.60 (1.41) | |

| Multiple information sources were incorporated. | 5.01 (1.69) | |

| Intuitive decision-makinga (Khatri and Ng, 2000; Kester, 2011) | We based our decision on what we felt to be right. | 4.15 (1.93) |

| We made the decision based on our own experience rather than on evidence. | 3.63 (1.87) | |

| When making the decision, we took into account firm member experience. | 4.68 (1.84) | |

| Political decision-makinga (Dean and Sharfman, 1996; Kester, 2011) | We had to negotiate and make concessions to get the decision approved. | 3.26 (1.78) |

| Our decision was conditioned by the stance of certain groups or individuals. | 3.19 (1.91) | |

| We had to accept the position of particular groups or individuals to gain approval for the deletion. | 2.91 (1.81) | |

| BD successb | Deletion of this brand has been good for the future of the company. | 8.31 (1.87) |

| The company achieved the goals for which the decision was made. | 8.42 (1.67) | |

| The deletion decision is considered a complete success. | 8.18 (1.96) | |

| Firm's prior economic situationa (Moorman and Rust, 1999; Verhoef and Leeflang 2009) | Our market performance was satisfactory. | 4.97 (1.60) |

| The company was performing well financially. | 4.98 (1.65) | |

| The company was experiencing substantial growth. | 4.58 (1.84) | |

| Experience in BDsc (Dayan and Elbanna, 2011) | Degree of experience in BD decisions. | 5.70 (2.55) |

| Formalizationa (Argouslidis, 2008; Argouslidis and Baltas, 2007) | A standardized or normalized procedure was used to execute the BD. | 5.00 (1.81) |

| An action plan was elaborated to guide the deletion process. | 5.40 (1.78) | |

| Milestones or deadlines that had to be met were set up. | 5.40 (1.70) | |

| The responsibilities of the members involved in the BD were pinned down. | 5.34 (1.79) | |

| The evolution of the deletion process was regularly monitored. | 5.36 (1.72) | |

Correlation matrix and discriminant validity.

| Cronbach-α | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Rational decision-making | .88 | .92 | .74 | .86 | .40 | .13 | .26 | .08 | .05 | .54 |

| 2. Intuitive decision-making | .81 | .88 | .72 | −.33 | .85 | .11 | .10 | .27 | .13 | .36 |

| 3. Political decision-making | .90 | .94 | .83 | −.07 | −.01 | .91 | .21 | .10 | .22 | .08 |

| 4. BD success | .92 | .95 | .86 | .24 | .08 | −.20 | .93 | .08 | .06 | .25 |

| 5. Firm's prior economic situation | .94 | .95 | .87 | −.02 | .25 | −.09 | .09 | .93 | .04 | .13 |

| 6. Experience in BDs | − | − | − | .03 | −.13 | .21 | .02 | −.04 | – | .20 |

| 7. Formalization | .94 | .96 | .81 | .50 | −.31 | .07 | .24 | −.14 | .20 | .90 |

Note: The diagonal elements (in bold) are the values of the square root of AVE. The values below the diagonal are the zero-order correlation coefficients. The elements above the diagonal (in gray) are the values of Henseler et al.’s (2015) HTMT ratio of correlations.

Measurement instruments are presented in Table 5. As stated before, the literature on BD is extremely scarce. Therefore, scales previously used in strategic decision-making literature were adapted to operationalize the three constructs measuring the firm's approach to BD decision-making. In particular, we adapted the scales used in the research by Papadakis et al. (1998), Khatri and Ng (2000) and Dean and Sharfman (1996), which have also been used by Kester (2011) in the context of research into NPD portfolio decisions. We elaborated a new scale to measure BD success, which reflects the level of satisfaction of the company with the outcomes of this decision. The choice of BD success as the dependent variable provides for a close link between the strategic decision-making process and its outcomes as well as it avoids the causal ambiguity associated with more general indicators of organizational performance (Dean and Sharfman, 1996; Elbanna and Child, 2007a; Shepherd and Rudd, 2012). Please, note that a perceptual construct of BD success is used.1

We incorporated the firm's prior economic situation as a control variable since this can affect the greater or less urgency to accomplish the BD as well as the reactions and perceptions concerning its impact on company performance. We operationalized this control variable with a three-item scale adapted from Moorman and Rust (1999) and Verhoef and Leeflang (2009). Considering Varadarajan et al.’s (2006) proposition, we also controlled for the effects of the firm having previous experience in similar strategies, as it could be expected that the accumulation of relevant knowledge will positively influence performance (Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1996; Golden and Zajac, 2001). A single-item scale, adapted from Dayan and Elbanna (2011), was used to operationalize the firm's experience in BDs. Finally, we controlled for the effects of formalizing the execution of the BD. Establishing standardized rules, protocols, deadlines and control mechanisms during the deletion process should help to ensure it is undertaken in an effective and timely manner (Argouslidis, 2008; Argouslidis and Baltas, 2007; Avlonitis and Argouslidis, 2012; Gounaris et al., 2006). Formalization was measured with five items adapted from the works by Argouslidis (2008), Argouslidis and Baltas (2007).

Analysis and resultsThe validity of the measurement instruments was assessed using the Partial Least Squares technique with the SmartPLS 3 software (Ringle et al., 2015). Reliability was examined by verifying that Cronbach's α and composite reliability (CR) values were all above .70 and that average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded the recommended minimum of .50 (Bagozzi et al., 1991). As reported in Table 6, discriminant validity was assessed by applying the well-known Fornell and Larcker (1981)’s criterion, which provided satisfactory results, as well as the criterion recently proposed by Henseler et al. (2015). According to this new criterion, based on the HTMT (heterotrait–monotrait) ratio of correlations, discriminant validity is established when the HTMT ratios do not exceed the .85 recommended threshold and their 90% bootstrapped confidence intervals do not include the value 1, conditions that are clearly met in our survey.

Moderated hierarchical regression analysis with the SPSS software (v.23) was used to test the hypotheses depicted in Fig. 1. As the nature of the main effects differs for models with and without interactions and may involve false and misleading conclusions (Henseler and Fassott, 2010), we sequentially introduced different blocks of variables to check their respective explanatory power. Firstly, in Model 1 we estimated the main effects of the focal and the control variables in our model. Secondly, in Model 2 we added the interaction effect between rational and political decision-making approaches (Model 2). Finally, in Model 3 we incorporated as predictors of BD success the two-way interactions between the three different approaches to BD decision-making and the type of BD (measured with a dummy variable in which a zero was assigned to BDs undertaken through total killing or disposal, and one was assigned to the cases of BDs through a brand name change). All model variables were mean-centered to avoid difficulties concerning interpretation of coefficients resulting from simultaneously including linear and interaction terms of the same variables in the same model (Echambadi and Hess, 2007). The standardized parameter estimates of the hypothesized and control relationships are presented in Table 7.

Standardized parameter estimates.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized relationships | |||

| Rational decision-making→BD success | .19* (H1) | .21* | .22** |

| Intuitive decision-making→BD success | .20** (H2) | .22** | .25** |

| Political decision-making→BD success | −.20** (H3) | −.20** | −.20** |

| Rational decision-making*Political decision-making→BD success | −.13* (H4) | −.14* | |

| Type of BD→BD success | .08 | ||

| Rational decision-making*Type of BD→BD success | .00 (H5) | ||

| Intuitive decision-making*Type of BD→BD success | −.02 (H6) | ||

| Political decision-making*Type of BD→BD success | .13* (H7) | ||

| Control relationships | |||

| Firm's prior economic situation→BD success | .04 | .04 | 03 |

| Experience in BDs→BD success | .05 | .05 | .06 |

| Formalization→BD success | .20* | .19* | .18* |

| R2 of BD success | .15 | .17 | .19 |

H1 predicts a positive relationship between rational decision-making and BD success. H1 is confirmed since said effect is positive and significant (β=.19, p<.05). H2, which postulates that the relation between intuitive decision-making and BD success is also positive, is likewise supported (β=.20, p<.01). The relationship between political decision-making and BD success is negative and significant (β=−.20, p<.01), as hypothesized in H3.

The results in Table 7 also show a negative and significant interaction effect between rational and political decision-making on BD success (β=−.13, p<.05) thus providing support for H4. The nature of this interaction has been examined using Aiken et al. (1991) procedure, which tests for the significance of regression coefficient estimates for the independent variables at one standard deviation below and above the mean of the moderating variable. At a low level of rational decision-making, the relationship between political decision-making and BD success is non-significant (β=−.09, n.s.), whereas at a high level of rational decision-making, a large and highly significant negative effect of political decision-making is found (β=−.32, p<.00) (Fig. 2).

The moderating effects of the type of BD predicted in H5 and H6 are rejected since the interactions of this dummy variable with the rational and the intuitive decision-making variables are both non-significant. In contrast, H7 is supported by the data since a positive interaction effect is observed between type of BD and political decision-making (β=.13, p<.05). This means that the negative effect of political decision-making on BD success is less negative when the firm is changing the brand name than when it is killing or selling the brand. In order to further explore this moderating effect, we compared the effect of the political decision-making approach on BD success across the two different types of BD. Henseler (2012)’s multi-group analysis based on PLS (PLS-MGA) was used to perform this comparison since it relies on a nonparametric test that does not require any distributional assumption. Table 8 shows the results for this test, revealing a significant difference across groups (p<.05) in the effect of political decision-making on BD success. In particular, results show that the negative effect of political decision-making on BD success is stronger (β=−.39, p<.01) when the brand was killed or sold to another company2 than when the brand was deleted through a name change, where the impact becomes insignificant (β=−.05, n.s.).

Standardized parameter estimates of multigroup analysis for total brand killing or disposal vs. brand name change.

| Group 1 Total brand killing or disposal (71 cases) | Group 2 Brand name change (84 cases) | |

|---|---|---|

| Political decision-making→BD success | −.39** | −.05 |

**p<.01 (one-tailed test). Significance levels based on bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals.

The model estimated is Model 2. No significant difference between groups is found for the rational and political decision-making interaction.

Rational, intuitive and political approaches, all of which potentially present in BD decision-making, are not equally recommendable because, whereas both rationality and intuition exert a positive effect on BD success, politics provokes a negative impact.

There is no controversy in the literature surrounding the result of the positive impact of rationality in success. What is more noticeable, however, is the positive effect of the intuitive approach on BD success. Our findings are in line with the literature highlighting the benefits of intuition in the cases of strategic (or non-routine) decisions characterized by incomplete knowledge. For example, intuition can be brought in after rational processes have done the groundwork and can provide data and analyses concerning the BD as the basis for intuitive processes (Sauter, 1999). Intuition could be a form of intelligence which decision-makers can use when they cannot access rational processes or can be used simultaneously (Fredrickson, 1985; Parikh et al., 1994). In addition, when compared to rationality, intuition has the advantage of requiring less resources and being fast, whereas rationality struggles to deal with discrepant information since this proves troublesome when determining the weight of such information (Bingham and Eisenhardt, 2011).

In line with previous research, we find support for a negative relationship between political behavior and the outcomes of BD (e.g., Dean and Sharfman, 1996; Gandz and Murray, 1980). Nevertheless, the strength of the negative relationship between political decision-making and BD success is contingent on two variables. First, it depends on the level of rationality. When a firm relies on a rational decision-making approach and bases the BD decision on objective and comprehensive information, having to negotiate and make concessions to particular groups might be perceived as a deviation from an optimal choice and may cause a feeling of frustration among those having access to the data that proves the BD is necessary and urgent. However, when the BD decision is adopted without robust evidence of the convenience of this initiative, political behavior is easier to justify as a result of the lack of objective information.

Second, in cases of brand name changes, political behavior does not play such a dysfunctional role as it does in cases of total brand killing or disposal. Political tactics such as negotiation or bargaining may prove appropriate vis-à-vis “selling the issue” and facilitating the path to implementing the changes required by the BD. Thus, this approach should not always be discarded since politics can serve as a mechanism for organizational acceptance of difficult decisions and for promoting the necessary strategic alignment (Eisenhardt and Zbaracki, 1992; Elbanna, 2006; Nutt, 1998). As Mintzberg (1998) points out, politics should be evaluated according to its effect on an organization's ability to pursue the appropriate mission efficiently in the long term since private political interests do not necessarily come into conflict with the common interests of the firm.

Conclusion, managerial implications, limitations and future researchThis paper offers an important contribution to the scarce BD literature. From an academic point of view, this study builds upon the more general literature on strategic decision-making and provides evidence in favor of Quinn's (1980) logical incrementalism. Compared to the synoptic formalism or the incremental perspective, which respectively emphasize the role of rationality and intuition, the logical incrementalism offer a more comprehensive and realistic view of decision-making as it acknowledges that rational, intuitive as well as political approaches are present and to some extent combined in the making of strategic decisions such as BD. It this sense, our investigation demonstrates that the way in which a firm approaches the decision to delete a brand from its portfolio affects the deletion outcomes and that all the three approaches are related to the perceived success of the decision. In particular, rational and intuitive decision-making approaches positively contribute to a successful BD. Therefore, this work adds empirical support to the mainstream of management research that defends a strategic decision-making process based on rational-intuitive assessment of information (e.g., Taggart and Valenzi, 1990). However, using a political approach exerts a negative influence on BD success. This negative effect is particularly harmful when decision-makers have objective information and empirical evidence to build a decision-making rationale but let the BD become contaminated by the possibly spurious interests of particular groups. Moreover, the negative effect is contingent on the type of elimination. The impact of the political approach is not statistically different from zero in the cases of BDs involving a brand name change. This probably occurs because, despite the generally detrimental influence of politics which is found, political behavior may well prove necessary and beneficial in terms of getting the BD decision accepted by the different organizational stakeholders and facilitating its implementation as well as adaptation to the new situation.

From a managerial point of view, the most important implication of our research is that managers have the power to influence the success of the BD. In this vein, we recommend that firms establish information systems which help decision-makers facing a BD decision to access the relevant data in order to decide accordingly and to provide evidence of the appropriateness of the strategy to be implemented. It is also necessary to make sure that management team members have the relevant expertise to rapidly and accurately assess the available evidence and to facilitate effective intuition, thus avoiding naïve intuition based on biased assumptions. As Khatri and Ng (2000) indicate, intuition can be developed through repeated exposure to the complexity of real problems, such intuition proving advantageous in the context of challenging and complex decisions such as a BD. In general, the political approach to BD decision-making should be minimized, particularly when managers have suitable information to base their decision on rational evidence. One exception to this general recommendation of minimizing political behavior is the situation in which the use of political tactics helps to overcome certain stakeholders’ initial rejection of the BD. This may be the case of BDs which simply involve a brand name change and where the business continues to operate in the market. In these instances, a political approach might not automatically lead to poorer performance. However, politics could jeopardize the success of the BD in cases involving total brand killing or disposal.

The results of this study must be interpreted bearing in mind certain limitations. First, we have used subjective measures based on the perceptions of a single respondent. Thus, even though we have verified that the respondents in our sample are knowledgeable informants and that there are no indications of a substantial CMB, our findings must be interpreted with due caution. Second, a more precise understanding of the causal relationships between decision-making approaches and BD success requires the use of a longitudinal research methodology combining qualitative and quantitative methods. A longitudinal design would help to more rigorously test our hypotheses by preventing respondent managers from giving their answers as a post hoc justification aimed at demonstrating the undeniable logic of their decisions, and would also enable cases to be investigated in which the decision-making process ended in the brand not being eliminated.

Apart from the necessary improvements in the measurement process, some other lines of further research can be suggested. First, we consider that BD decision-making cannot be fully understood unless the “context” of the decision-making is taken into account. For example, it would be interesting to explore the contingent effect of the environmental uncertainty on the relationship between intuition-based decision-making and BD success. As the literature proposes, in times of change, subjective rationality based on opinions and intuitive synthesis enables experienced senior managers to size up a situation, integrate and synthesize large amounts of data, and also to deal with incomplete information. Quinn (1980) even suggested that, because of the subtle and qualitative balances it can embrace, intuition is probably superior to any rigorous model in a high-velocity environment. Second, our definition of political behavior assumes that its impact on BD success is largely negative or dysfunctional, which is consistent with much of the previous literature. However, it has also been criticized for ignoring possible positive or functional aspects (Fedor et al., 2008). Future studies should adopt a broader and more neutral definition of political behavior such as the one by Child et al. (2010), who define it as “action (s) taken by decision makers in order to serve their own interests or these of the organization”. Clearly, this definition raises the issue of the multidimensional nature of political behavior. Finally, future research must consider the impact of BD implementation on BD performance so as to complete the model of strategic decision-making and success. As Nutt (1999) suggests, the key reasons for failure occur predominantly during decision implementation rather than during decision-making. Thus, beyond the satisfaction generated by the decision-making approach, much more academic work is required to better understand how the implementation determines the success of BDs.

FinancingEuropean Social Fund (ESF) and Junta de Castilla y León (Spain), ORDEN EDU/828/2014, and European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). Junta de Castilla y León (Spain), project reference VA112P17. Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad, Plan Estatal de Investigación Científica y Técnica y de Innovación 2013-2016, project reference ECO2017-86628-P.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest in this article.

Authors want to express their immense gratitude to Prof. John Rudd (Head of the Marketing Group, Warwick Business School) for his insightful comments on earlier versions of this paper. We also thank the support of Corporate Excellence – Centre for Reputation Leadership in the data gathering process.

In contrast with other alternative measures, such as economic performance, our scale of BD success is applicable to any BD decision, whatever the industry, the context or the reasons to make this decision. In this sense, a BD can be considered successful/unsuccessful even though negative/positive economic results had been observed after the deletion. For example, if the BD was motivated by a lack of strategic fit with the corporate strategy, the success of the decision does not necessarily reflect in superior profits or sales figures, at least in the short term, but improved corporate reputation should be observed.

A priori the cases of total brand killing and of brand disposal were categorized as a single group of more risky and irreversible BDs. As a robustness check, we run separate analyses for the 53 cases of total brand killing and the 18 cases of brand disposal and the findings are consistent. That is, the standardized parameter estimate of the relationships between political decision-making and BD success is negative and significant for total brand killings as well as for brand disposals.