This paper simultaneously analyzes antecedents and consequences of organizational ambidexterity. Regarding antecedents, the paper examines the influence of internal antecedents (organizational structure) and external antecedents (environmental dynamism). With regard to consequences, the paper analyzes the impact of ambidexterity on firm performance. Moreover, we use two different approaches to ambidexterity (structural and contextual perspectives). The findings show that a hybrid organizational structure, with organic (decentralization) and mechanistic characteristics (differentiation and formalization), and environmental dynamism, influence ambidexterity, and there is a positive impact of ambidexterity on firm performance.

Ambidexterity is an interesting research topic in strategic management and organization theory. Prior studies have indicated that successful organizations are ambidextrous (March, 1991; Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996), developing exploration and exploitation activities simultaneously. A key issue for a firm is to carry out exploitation activities to ensure its current viability and to develop exploration activities to ensure its future viability (Levinthal and March, 1993). Tushman and O’Reilly (1996) conceptualize the ambidextrous organization as a firm that has the ability to compete in mature markets (where efficiency and incremental innovation are crucial) at the same time as developing new products for emerging markets (where experimentation and flexibility are critical). Therefore, together with the importance of ambidexterity as an academic research topic, ambidexterity is also relevant for management practice, taking into account the characteristics of the competitive environment where firms operate and thus the need to implement both exploitation and exploration activities.

Organizational ambidexterity is in the process of being developed into a new research paradigm and much remains to be understood (Birkinshaw and Gupta, 2013; O’Reilly and Tushman, 2013; Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008; Simsek, 2009). As indicated below in the background section, some works have explored how organizations can become ambidextrous by studying the main antecedents, determinants or enablers (usually one antecedent), whereas other studies have focused on consequences of implementing organizational ambidexterity. Recent studies (Herhausen, 2016; Junni et al., 2015; Wu and Wu, 2016) suggest that more empirical research is needed in different environmental conditions, including not only consequences but also the combination of several antecedents of organizational ambidexterity. According to Simsek (2009), integrative models are needed. This paper addresses this gap. Examining only the influence of one aspect (internal factor or external context) on ambidexterity may lead to an incomplete explanation of the determinants of organizational ambidexterity and its impact on firm performance. There are theoretical studies and reviews that highlight the need of a joint analysis of internal and external aspects (Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008; Simsek, 2009). However, to the best of our knowledge, no empirical study has jointly examined the influence of internal and external elements on ambidexterity and the performance consequences of this organizational ambidexterity. The joint analysis of several antecedents and performance consequences is an interesting and relevant topic, both for academic research, in order to reach a more complete perspective of organizational ambidexterity, and for management practice. When managers make decisions (for example, to achieve organizational ambidexterity), they must consider as determinants or antecedents both internal aspects of their firms and external issues of the environment, and a key point is also the effect of ambidexterity on firm performance. We address this joint analysis in our paper.

In addition, according to Junni et al. (2015), further understanding of ambidexterity may require not only examining the joint effects of multiple variables as antecedents of organizational ambidexterity, but also different approaches to study organizational ambidexterity. In this regard, the literature about ambidextrous organizations uses different approaches. O’Reilly and Tushman (2013) identify three main approaches: sequential, simultaneous or structural, and contextual ambidexterity. As we will examine in the next section, studies to date have typically employed only one approach to analyze organizational ambidexterity (Simsek, 2009). In this paper, we focus on two of these approaches at the same time: the structural and contextual perspectives. Therefore, our work addresses the gap in the literature regarding the need of integrative models (internal and external antecedents, consequences, and different approaches of organization ambidexterity).

For this study, we have selected relevant internal and external factors, which also try to address some gaps. Among internal antecedents, organizational structure may play a key role in the implementation of ambidexterity (Csaszar, 2013). The study of organizational structure is important because the implementation of any management system, strategy or activity needs an appropriate organizational structure. The organizational structure is an essential support for all the activities in the organization. Therefore, managers should design a suitable organizational structure for implementing ambidexterity. Previous studies have emphasized that organizational ambidexterity involves differentiated organizational units (Benner and Tushman, 2003; Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996), and that ambidextrous companies need to use integration mechanisms to increase knowledge flows across exploitation and exploration organizational units (Jansen et al., 2009). However, there is little empirical evidence on the specific characteristics of organizational structure that companies should adopt to develop exploratory and exploitative activities at the same time (Jansen et al., 2005, 2009). According to this, we analyze differentiation, decentralization and formalization as possible organizational structure characteristics that may favor not only the separate development of exploration and exploitation activities, but also their integration. We examine these organizational structure variables because (a) the mainstream literature on organizational design considers differentiation, centralization and formalization as the main variables to characterize the structure of an organization (Hage and Aiken, 1967; Khandwalla, 1977; Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967), and (b) Junni et al. (2015) point out that empirical evidence regarding the relationship between these organizational variables and organizational ambidexterity remains largely based on case studies, and that future quantitative research should address the impact of differentiation, centralization and formalization on ambidexterity to improve our understanding about the role of organizational structure in organizational ambidexterity.

External antecedents may also influence organizational ambidexterity. Although current models of exploration and exploitation generally presume there is environmental dynamism, they actually give little consideration to features of environment (Kim and Rhee, 2009). There is some empirical evidence that a more dynamic environment leads an organization to pursue exploration (Sidhu et al., 2004). However, as competition intensifies, organizations should renew themselves by exploiting existing capabilities and exploring new ones (Jansen et al., 2006). In spite of the importance of the characteristics of environment, few studies have analyzed the relationship between environmental dynamism and organizational ambidexterity. Researchers have argued that environmental factors such as dynamism can require firms to become ambidextrous, and that more studies analyzing how environmental conditions directly influence a firm's organizational ambidexterity are needed (Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008). Therefore, we analyze environmental dynamism because it can be a relevant antecedent of ambidexterity.

Regarding consequences of ambidexterity, research should provide a more fine-grained understanding of the ambidexterity-performance link as noted by recent studies (Junni et al., 2013; Nosella et al., 2012; O’Reilly and Tushman, 2013; Simsek et al., 2009). Some works found a direct positive relationship between ambidexterity and performance (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004; He and Wong, 2004; Lubatkin et al., 2006). Others have found a contingent effect (Cao et al., 2009), or a negative effect (Atuahene-Gima, 2005), while yet others have found no empirical support (Venkatraman et al., 2007). Therefore, empirical evidence is inconsistent regarding the performance implications of organizational ambidexterity (Zhang et al., 2015) and then more research is needed because performance consequences of ambidexterity is a relevant issue for managers.

Thus, the purpose of the paper is to analyze the influence of internal antecedents (differentiation, centralization and formalization) and external antecedents (environmental dynamism) on organizational ambidexterity, and the influence of organizational ambidexterity on firm performance. In addition, there is also a need for research examining organizational ambidexterity in a broader spread of industries (Cao et al., 2009; Jansen et al., 2005). For example, Jansen et al. (2005; 2006) conducted their studies in a large European financial services firm; He and Wong (2004) studied manufacturing firms; and Cao et al. (2010) analyzed small and medium Chinese firms from several high tech industries. Our paper extends previous research by examining large firms in several industries. Furthermore, we also use a new way to measure ambidexterity as a second order formative construct.

The paper is organized as follows. First, the theoretical framework and hypotheses are presented. Then, the main characteristics of methods employed in this empirical study are described. Next, the results are presented. Finally, a discussion of these findings, together with main implications and conclusions, is provided.

Theory and hypothesesBackgroundAn important topic in the field of ambidexterity is the analysis of its antecedents and consequences. Regarding antecedents, empirical works have usually examined only internal factors, such as organizational characteristics (Jansen et al., 2005, 2009), organizational culture (Lee et al., 2017), leadership (Jansen et al., 2008; Keller and Weibler, 2015), top management teams attributes (Cao et al., 2010) and several aspects related to human resources (Junni et al., 2015). Some studies have analyzed specific external factors, mainly characteristics of environment such as its dynamism, rates of change, complexity or munificence (Jansen et al., 2006; Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008). Regarding consequences, several specific aspects have also been examined. Some works have analyzed new product development (De Visser et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2014), financial performance (Cao et al., 2009; Lubatkin et al., 2006), export venture performance (Hughes et al., 2010) or corporate venture survival (Hill and Birkinshaw, 2014). As indicated above, no empirical study has jointly examined the influence of both internal and external elements on ambidexterity together with the performance consequences of this organizational ambidexterity. The present paper addresses this gap taking into account these elements and impacts.

Moreover, literature uses different approaches to study organizational ambidexterity. O’Reilly and Tushman (2013) identify three main approaches: sequential, structural and contextual ambidexterity. Sequential ambidexterity refers to a temporal cycle through periods of exploration and periods of exploitation. Therefore, it can create ambidextrous organizations in the longer term. This temporal separation overcomes the difficulties of a simultaneous trade-off, rotating efficiency and renewal focused periods, but it might also result in high costs of mode switching (Goossen and Bazazzian, 2012). The structural approach proposes that is possible to pursue exploration and exploitation activities simultaneously. In this simultaneous or structural approach, some studies defend an internal or intra-organizational ambidexterity, that is, to develop exploration and exploitation activities in separate or differentiated organizational units (Diaz-Fernandez et al., 2017; Jansen et al., 2009). Other works analyze inter-organizational ambidexterity, that is, to externalize exploitative or explorative activities through outsourcing or by establishing alliances (Stettner and Lavie, 2014). Finally, contextual ambidexterity refers to the possibility of pursuing the two activities simultaneously and internally (Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008). In this regard, Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004) propose that the tension between exploitative and explorative activities could be resolved at the individual level, through a supportive organizational context that encourages individuals to integrate exploration and exploitation activities. This context should be designed to enable and encourage all members of the organization to judge for themselves how to best divide their time between the contradictory demands for exploration and exploitation. Related to this contextual approach, some researchers also describe a leadership approach that makes top management team responsible for responding to the tensions between the two activities (Cao et al., 2010; Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008). Recently, researchers have begun to investigate some characteristics and processes that enable top management teams to simultaneously pursue exploitation and exploration (Keller and Weibler, 2015; Lubatkin et al., 2006).

Empirical research to date has typically employed only one approach to study organizational ambidexterity (Simsek, 2009). In the present paper, we focus on two approaches at the same time: the structural and contextual perspectives to analyze if some organizational structure variables (such as differentiation, centralization and formalization) may jointly favor the organization to become ambidextrous. We study large firms, and the structural approach may be more appropriate for this type of firms (Lubatkin et al., 2006). In this regard, we analyze differentiation as a characteristic of organizational structure in this structural approach. However, the presence of exploitative and exploratory activities in different organizational units does not ensure the simultaneous pursuit of exploitation and exploration (Jansen et al., 2009). Thus, we also focus on the contextual approach, since decentralization and formalization can influence the behavior of individuals in achieving a balance between exploration and exploitation.

Internal antecedents of ambidexterity: the role of organizational structureSome authors point out that exploration and exploitation require completely different organizational characteristics (Gupta et al., 2006; Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008). While exploitation is associated with actions such as “refinement, efficiency, selection, and implantation”, exploration refers to activities such as “search, variation, experimentation, and discovery” (March, 1991; Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008). Then, exploration and exploitation activities may require different organizational designs, contexts and strategies. On the one hand, exploration is associated with organic structures, path breaking, loosely coupled systems, improvisation, autonomy, and emerging markets. On the other hand, exploitation activities are linked to mechanistic structures, routinization, path dependence, bureaucracy, and stable markets (He and Wong, 2004).

Because exploration and exploitation require seemingly contradictory organizational characteristics, previous research has argued that companies have to separate exploitation from exploration in different organizational units (Benner and Tushman, 2003; Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996), which refers to structural differentiation. Lawrence and Lorsch (1967) define structural differentiation as “the state of segmentation of the organizational systems into subsystems, each of which tends to develop particular attributes in relation to the requirements posed by it relevant external environment”, that is, the subdivision of organizational tasks and domains across units (Jansen et al., 2012).

Such structural separation ensures that each organizational unit is configured to the specific needs of its task environment (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967). For example, core business units may focus on alignment and exploitation, while units as Research and Development or business development may emphasize exploration (Diaz-Fernandez et al., 2017).

Therefore structural differentiation may help ambidextrous firms to maintain several capabilities that address conflicting demands (Gilbert, 2005). In this regard, structural differentiation emphasises differences across units in terms of mindsets, time orientations, and product/market domains (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967). In ambidextrous companies, structural differentiation may result in exploitative and exploratory units in different places (Benner and Tushman, 2003; Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996). Therefore, these firms allow the coexistence of conflicting efforts at different parts of the organization.

Relying on insights from organizational learning theory (Levinthal and March, 1993; March, 1991) several scholar have argued that simultaneously conducting exploitative and explorative activities is not a simple task as these activities require different capabilities and organizational routines (Diaz-Fernandez et al., 2017). Therefore, structural differentiation can be an effective organizational characteristic to address the tension between exploration and exploitation. In this way, each type of activity gets its own organizational space (De Visser et al., 2010). Structural differentiation provides organizational units with a sense of freedom and ownership over their activities, which allows higher creativity and adaptation to specific demands. Through structural differentiation, each organizational unit can adopt working methods that are better suited for their specific exploration or exploitation activities (Burgers et al., 2009).

Moreover, differentiation protects current operations in exploitative units from interfering with emerging capabilities that are developed in exploratory units. Thus, exploratory units can enjoy the flexibility to develop new knowledge and skills (Jansen et al., 2009). Therefore, we propose that:Hypothesis 1 Structural differentiation will positively influence ambidexterity.

Although structural differentiation may be an important organizational characteristic to address conflicting demands of exploration and exploitation activities, from the contextual approach of ambidexterity, other organizational variables (like decentralization and formalization) can also favor the simultaneous pursuit of exploration and exploitation whether there is structural differentiation or not. We explain this issue in the following two hypotheses.

Regarding centralization, Hage and Aiken (1967) pointed out that it refers to the concentration of decision making in an organization, while decentralization of decision-making is a consequence of the distribution of authority among the different organizational levels and members (Fredrickson, 1986). Considering the organization as a whole, decentralization is needed for the adequate development of separate exploratory and exploitative activities because it provides autonomy to the different units to make adjustments and modifications unilaterally (Foss et al., 2015). Moreover, decentralization increases the likelihood that individuals in the firm seek innovative solutions (Damanpour, 1991). In a more decentralized organization, organizational members may be more motivated and committed in assessing and using information to pursue organizational ambidexterity (Cao et al., 2010). Decentralization can favor both exploitative and explorative activities.

Exploratory activities require deviation from existing knowledge and non-routine problem solving, in order to identify emerging customer demands, new products, services or technologies far from existing ones (Wei et al., 2011). Decentralization facilitates ad hoc problem solving that increases the range of feasible responses to problems and helps individuals to carry out exploratory activities (Jansen et al., 2005). Decentralized decision-making processes improve information flows (Hempel et al., 2012), and facilitate to recognize the changes of customer demands, technological developments and market opportunities which are crucial for exploration (Wei et al., 2011). Conversely, centralization reduces the quantity of information decision makers receive, because cognitive capacities are limited and communication costs are high in terms of the effort for obtaining the CEO's approval (Cao et al., 2010). It also reduces the quality of information received because specialization of work at each level leads to perceptual differences that distort communicated information (Sheremata, 2000). Then, centralization may reduce exploratory innovation (Jansen et al., 2006).

Jansen et al. (2006) point out that exploitative activities are limited in scope and newness, and problem solving related to exploitation activities can be seen as more routine. Hence centralized decision makers do not have to process large amounts of information. However, good ideas about how to solve a problem can often be generated only by organizational members close to the source of the problem. Thus, although centralized decision makers do not have to process large amounts of information related to exploitation activities, information in centralized organizations travels through a long filtering process before it reaches decision makers (especially in large firms), and transmission distorts the information they do receive (Sheremata, 2000). Therefore, centralization reduces the quality of information decision makers receive, and consequently, it does not favor exploitation activities either.

According to Foss et al. (2015), decentralization gives lower-level members discretion in adjusting the tactics they use to pursue new opportunities based on market feedback, and enables the efficient use of knowledge that is located at lower levels in the organization. In this way, decentralization can favor exploitation activities. It may increase flexibility at the operational level, which allows the firm to respond to emerging opportunities faster, facilitating ambidextrous behavior at lower hierarchical levels (Mihalache et al., 2014). On the contrary, centralization reduces the effectiveness of upper-level decision makers in capturing market opportunities, because of the incomplete and inaccurate information they receive (Jansen et al., 2012).

Based on the knowledge management and organizational learning literature (Lee and Choi, 2003; Nonaka et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2011), decentralization is more likely to encourage spontaneity, experimentation, the circulation of ideas, and creativity (Lee and Choi, 2003). In decentralized organizations, individuals are exposed to a greater number of opinions and amounts of information, which may lead to a creative integration of perspectives. Decentralized decision-making processes can foster knowledge creation by motivating organizational members’ involvement (Liao, 2007). Therefore, decentralization toward the lower levels in the organization can facilitate the creation of new knowledge and also their use, because the more organizational members become involved in the decision-making process, the more diversity and number of ideas can arise, and the more likely these ideas will be to materialize in exploration or exploitation activities (Pertusa-Ortega et al., 2010).

In centralized organizations, managers might be unable to catch the information in a timely manner to take advantage of both exploration and exploitation activities. Conversely, decentralized decision-making creates a context for sharing new ideas which may diverge greatly from existing knowledge, favoring exploration activities, but also for sharing ideas to improve the exploitation of the existing business models, technologies, products or services, encouraging exploitation activities (Wei et al., 2011).

In short, centralization will have a negative impact on the development of exploration and exploitation activities, and consequently on ambidexterity. Decentralization can play a dual role: from the structural point of view, it supports the adequate development of separate exploratory and exploitative activities, because they need autonomy to operate, and from the contextual point of view, it creates an organizational context in which individuals may be more motivated and involved in developing exploration and exploitation activities.Hypothesis 2 Centralization will negatively influence ambidexterity.

From the structural point of view, integration mechanisms are needed to integrate diverse resources across differentiated exploitation and exploration (Jansen et al., 2009). In this regard, formalization (that is, the degree to which rules, procedures, instructions, and communication are formalized or written down (Khandwalla, 1977)) is an integration mechanism that can facilitate interfunctional transfer of information and knowledge across differentiated exploratory and exploitative activities and improve department members’ awareness of that information and knowledge (Pertusa-Ortega et al., 2010). Formal interventions may improve the integration of knowledge into firm units, so that knowledge can be introduced and used more effectively (Filippini et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2011). Katila and Ahuja (2002) argue that exploitation of existing resources and activities may be needed to explore new resources and activities, and exploration also may help enhance existing resources and knowledge for future exploitation. Thus, exploitation and exploration activities form a dynamic path of absorptive capacity (He and Wong, 2004). Formalization can favor this dynamic path, because the new knowledge that results from exploration activities can be codified in procedures that help organizations to diffuse exploratory innovation, and therefore, its future exploitation. In other words, formalization helps in the exploitation of existing capabilities and routines, disseminating that knowledge across the organization, and at the same time, formalization facilitates the replication and diffusion of exploratory innovations through new knowledge (Jansen et al., 2006). Therefore, formalization may help to integrate exploratory and exploitative activities.

However, from the contextual approach of ambidexterity, the effect of formalization within differentiated organizational units must be taken into account. In this regard, following Adler and Borys (1996), it is interesting to examine two different types of formalization: coercive and enabling formalization.

On the one hand, regarding coercive formalization, Adler and Borys (1996) indicate that this formalization refers to rules and procedures of compulsory compliance without any leeway (Johari and Yahya, 2009; Sinden et al., 2004). Earlier literature often claimed that reliance on procedures may hinder experimentation (March and Simon, 1958). This earlier literature could be considering a coercive kind of formalization. From this perspective, coercive formalization may restrict the creation of new knowledge and may constrain exploratory efforts (Von Krogh, 1998). It hampers deviation from current knowledge and the range of new ideas appears to be restricted when strict formal rules govern a company (Lee and Choi, 2003). Therefore, a strict and coercive use of formalization can constrain exploratory activities (Jansen et al., 2006). Instead of providing organizational members with access to organizational knowledge, coercive formalization forces compliance to rules. Thus, coercive formalization limits the flexibility needed to experiment and to move away from current knowledge, capabilities and routines, and then it limits exploration activities. In the same way, current problem solving and the introduction of incremental improvements in the organization (exploitation activities) are not improved by blind obedience to the rules either. Instead of promoting organizational learning, coercive formalization brings about job dissatisfaction, stress and job absenteeism (Sinden et al., 2004). In these circumstances, employees become alienate, as employees are to perform work instructions assigned, without being given any rationale (Johari and Yahya, 2009). Consequently, it creates a loss of creativity, flexibility and motivation (Vlaar et al., 2006). Coercive formalization can be more related to bureaucratic obstacles that limit flexibility and innovativeness of any kind (exploration and/or exploitation) (Hempel et al., 2012), as this coercive formalization expects blind adherence to rules, promotes control, discourages changes, punishes mistakes, views problems as obstacles, and discourages innovation (Sinden et al., 2004). In summary, coercive formalization hinders exploration and exploitation activities, and consequently, it will negatively influence ambidexterity.Hypothesis 3 Coercive formalization will negatively influence ambidexterity.

On the other hand, a different type of formalization must be considered, namely enabling formalization. According to Adler and Borys (1996), enabling formalization refers to rules and procedures that capture and codify best-practice, designed with a wide range of contextual information to help employees interact creatively with the broader organization and environment. Jansen et al. (2006) point out that formalization may make it easier to respond to the current environment in a known way. It may facilitate the improvement of routines and practices that increase efficiency and ease the application of new knowledge. This view of formalization would be more related to enabling formalization. Thus, enabling formalization may emphasize exploitative innovation through improvement of current products and processes.

Enabling formalization can help individuals do their tasks effectively, because it may help them solve current work problems. This kind of formalization includes flexible procedures and guides that help employees deal with difficulties and dilemmas (Sinden et al., 2004). In this regard, enabling formalization mobilizes rather than replaces employees’ intelligence and acts to help users form mental models of the activities they are carrying out, and modify them if necessary to add functionality to suit their specific work demands (Johari and Yahya, 2009; Wouters and Wilderom, 2008). Thus, it can promote the introduction of improvements in present tasks, and therefore, it can favor exploitation activities. In addition, enabling formalization can not only help to develop exploitation activities but also exploration activities because it helps maintain some degree of flexibility and strengthen the involvement and motivation of employees. In this regard, enabling formalization is designed to afford employees an understanding of where their own tasks fit into the whole (Wouters and Wilderom, 2008), and this can encourage individuals to interact creatively and the development and exploration of new processes and/or activities. In sum, enabling formalization promotes flexibility, learning from mistakes, views problems as new opportunities, facilitates problems solving, and it may encourage any kind of innovation. Therefore, enabling formalization may positively influence exploration and exploitation activities, and then, it can favor ambidexterity.Hypothesis 4 Enabling formalization will positively influence ambidexterity.

Environmental dynamism refers to the rate of change and the degree of unpredictability of change (Dess and Beard, 1984). In a dynamic environment, products become obsolete rapidly and new ones are needed. Exploratory innovations help firms deal with obsolescence of products. However, without exploitation of the results of exploration, rivals may imitate exploration activities and launch a new version at lower cost. Therefore, firms have to balance exploration of new opportunities and exploitation of existing resources (Jansen et al., 2005). That is, organizations that operate in dynamic environments needs to pursue both types of innovation and be ambidextrous. Other studies have suggested that in more stable environments sequential ambidexterity may be more useful (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2013).

With high dynamism, firms must innovate in products and explore new markets. But the consequences of exploration are uncertain. Therefore, organizations will also need exploitation activities to maintain their competitive position. Without this balance, organizations may lose their position through diverting their resources to exploratory activities, the benefits of which might or might not materialize. Then, firms need to complement exploration with exploitation (Aug and Menguc, 2005). For instance, Jansen et al. (2006) show that exploitation activities perform better when the environment changes slowly, but as environmental dynamism increases, balancing exploitation and exploration becomes more important (Kim and Rhee, 2009).Hypothesis 5 Environmental dynamism will positively influence ambidexterity.

Despite the challenges involved (Stettner and Lavie, 2014) and the risk of being mediocre at both exploitation and exploration (March, 1991), organizations that are able to pursue exploration and exploitation simultaneously may achieve better performance than other organizations (Junni et al., 2013; Nosella et al., 2012; O’Reilly and Tushman, 2013; Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996). Exploitation activities may help transform firm resources into commercial ends, but without exploratory efforts a firm's stock of knowledge will become obsolete. Likewise, exploration activities may help continuous renewal and expand the knowledge base, but without exploitation that knowledge may not be fully used. Thus, the two kinds of innovation are mutually reinforcing (Andriopoulos and Lewis, 2009), and therefore, may be beneficial for firm performance.

Concentration on exploitative activities may improve short-term performance, but it may result in a competency trap because organizations may not be able to respond to market changes (Leonard-Barton, 1992). Conversely, too much exploratory activities may improve an organization's capability to renew its knowledge base but can trap firms in an endless and unrewarding cycle of search (Volberda and Lewin, 2003). Combining exploitation and exploration helps firms to overcome structural inertia that results from focusing on exploitation, and also prevents them from accelerating exploration without achieving benefits (Levinthal and March, 1993).Hypothesis 6 Ambidexterity will positively influence firm performance.

This study focuses on Spanish firms that are not subsidiaries of a larger corporation or group, to avoid the possible transfer of exploration and exploitation activities within the group, as the subject of this study is the simultaneous internal development of exploitation and exploration activities (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004; Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008; Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996). Organizations were selected that had 250 or more employees, i.e. “large firms” according to the Recommendation 2003/361 of the European Commission, and more than three years of operation. We focus on large firms because we wanted to analyze organizational structure characteristics that were actually a decision of the organization, and not just a consequence of the small size. For instance, a small or medium firm is usually more centralized than a large firm because there are fewer hierarchical levels to decentralize. After collecting data from various directories (Duns 50,000 Main Spanish Firms; and SABI (Iberian [Peninsula] Balance Analysis System) database), a population of 1903 companies from different industries was selected.

Data was collected through a mail survey to the Chief Executive Officer (CEO). Following the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (2003), a number of steps were taken to reduce the potential risk of common method bias from the use of a single respondent. Firstly, we tried to ensure that informants were committed by assuring them of confidentiality. Secondly, the items were carefully constructed to avoid any potential ambiguities. Multiple-item constructs were used in the data analysis. Response bias is more problematic at the item level than the construct level (Harrison et al., 1996). This is an area where structural modeling approaches are useful in avoiding the problems related to item-level analysis (Harrison et al., 1996). Thirdly, we used Harman's single factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The unrotated solution produced several factors, none of which accounted for the majority of the variance.

A preliminary draft of the questionnaire was discussed with some experts. Then, a pilot test was carried out, in which personal interviews were conducted with the CEOs of five companies. Then, the final questionnaire was distributed. One month after the initial mailing, a follow-up letter was sent in order to increase the response rate (Dillman, 2000). Finally, 164 organizations participated in the study.

To check for non-response bias, we studied differences between respondents and non-respondents for the final sample. χ2 and t difference tests revealed no significant differences based on the industry and the number of workers, respectively. We also compared early and late respondents in terms of model variables (Armstrong and Overton, 1977). These analyses did not show any differences.

Of the 164 organizations that participated in the study, approximately 40% were manufacturing firms and 60% service companies. The mean size of those firms was 1227.55 employees, with a minimum of 250 and a maximum of 27,000. The sample includes nine high-technology manufacturing firms, 17 medium-high technology manufacturing firms, 36 knowledge-based service firms, eight medium-low technology manufacturing firms, 42 low-technology manufacturing firms, and 52 non-knowledge-based service firms.

MeasurementAmbidexterity. Regarding the ambidexterity measurement, there is no consensus between researchers. Some researchers consider ambidexterity to be a bi-polar construct treating exploitation and exploration as the opposite ends of a single continuum (Simsek et al., 2009). Other researchers consider exploitation and exploration innovation as orthogonal (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004; He and Wong, 2004; Jansen et al., 2009), that is, as two distinct dimensions rather than as two ends of a unidimensional scale (Stettner and Lavie, 2014). Within this second approach there are also different ways of measuring ambidexterity: adding (Lubatkin et al., 2006), multiplying (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004), and subtracting (He and Wong, 2004) exploitation and exploration dimensions.

In this study, we adopt the orthogonal approach, more extended in previous research, that is, we consider ambidexterity to be a multidimensional construct, with exploration and exploitation each constituting a separate non-substitutable element (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004). However, different from previous studies, we have measured ambidexterity as a second-order construct consisting of two formative dimensions: exploitation and exploration. To measure each of these dimensions we asked for the firm's efforts to develop exploration and exploitation activities, using He and Wong's (2004) scales (Table 1), which proved to be highly reliable (Cao et al., 2009).

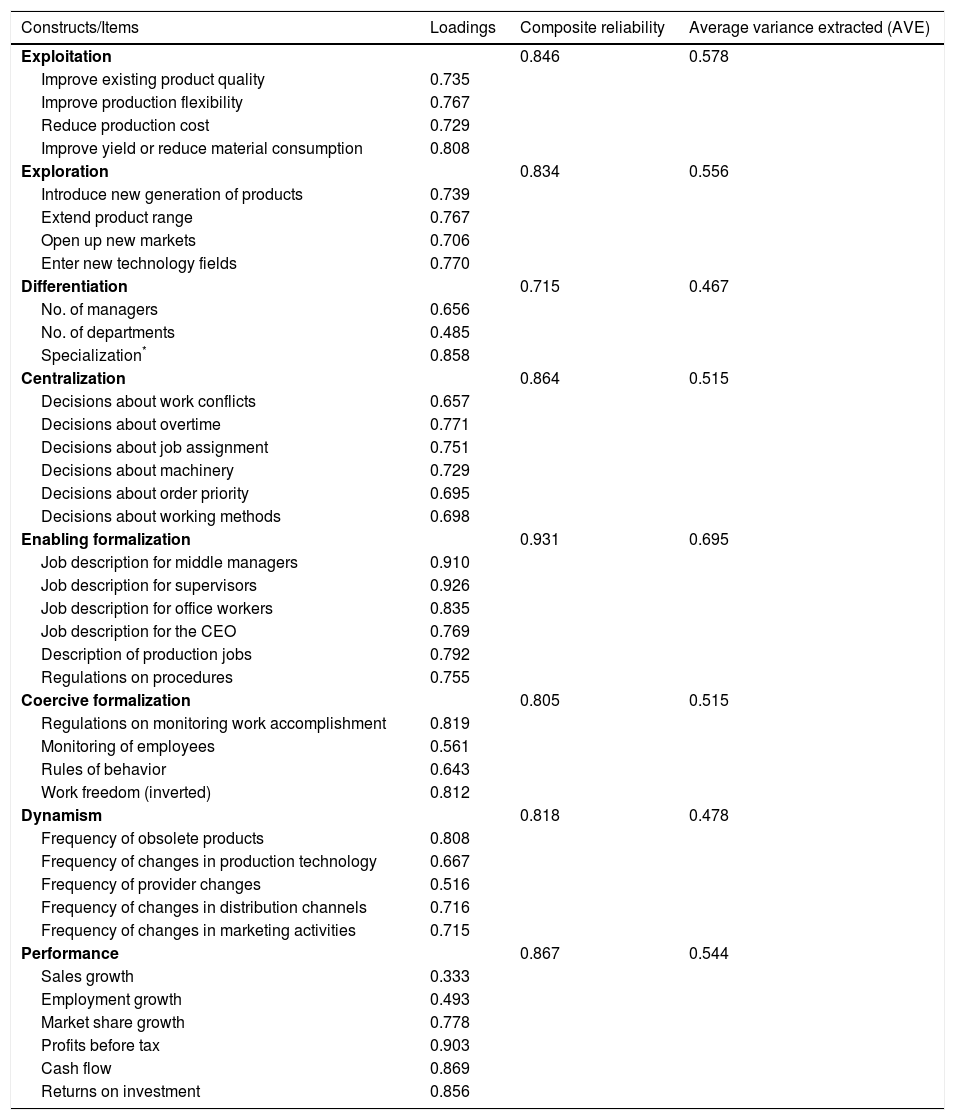

Measurement model evaluation.

| Constructs/Items | Loadings | Composite reliability | Average variance extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploitation | 0.846 | 0.578 | |

| Improve existing product quality | 0.735 | ||

| Improve production flexibility | 0.767 | ||

| Reduce production cost | 0.729 | ||

| Improve yield or reduce material consumption | 0.808 | ||

| Exploration | 0.834 | 0.556 | |

| Introduce new generation of products | 0.739 | ||

| Extend product range | 0.767 | ||

| Open up new markets | 0.706 | ||

| Enter new technology fields | 0.770 | ||

| Differentiation | 0.715 | 0.467 | |

| No. of managers | 0.656 | ||

| No. of departments | 0.485 | ||

| Specialization* | 0.858 | ||

| Centralization | 0.864 | 0.515 | |

| Decisions about work conflicts | 0.657 | ||

| Decisions about overtime | 0.771 | ||

| Decisions about job assignment | 0.751 | ||

| Decisions about machinery | 0.729 | ||

| Decisions about order priority | 0.695 | ||

| Decisions about working methods | 0.698 | ||

| Enabling formalization | 0.931 | 0.695 | |

| Job description for middle managers | 0.910 | ||

| Job description for supervisors | 0.926 | ||

| Job description for office workers | 0.835 | ||

| Job description for the CEO | 0.769 | ||

| Description of production jobs | 0.792 | ||

| Regulations on procedures | 0.755 | ||

| Coercive formalization | 0.805 | 0.515 | |

| Regulations on monitoring work accomplishment | 0.819 | ||

| Monitoring of employees | 0.561 | ||

| Rules of behavior | 0.643 | ||

| Work freedom (inverted) | 0.812 | ||

| Dynamism | 0.818 | 0.478 | |

| Frequency of obsolete products | 0.808 | ||

| Frequency of changes in production technology | 0.667 | ||

| Frequency of provider changes | 0.516 | ||

| Frequency of changes in distribution channels | 0.716 | ||

| Frequency of changes in marketing activities | 0.715 | ||

| Performance | 0.867 | 0.544 | |

| Sales growth | 0.333 | ||

| Employment growth | 0.493 | ||

| Market share growth | 0.778 | ||

| Profits before tax | 0.903 | ||

| Cash flow | 0.869 | ||

| Returns on investment | 0.856 |

A formative approach is adequate when the indicators help to create the construct directly, while a reflective specification assumes that indicators reveal various features of an underlying construct (Chin, 1998a). The choice of a measure of ambidexterity as a second-order construct requires the selection of a molar or a molecular approach to analysis. While the molar approach views second-order factors as emergent constructs formed from first-order factors (formative dimensions), the molecular approach is based on the assumption that an overall latent construct exists, and that it is indicated and reflected by first-order factors (reflective dimensions) (Chin and Gopal, 1995). The choice depends primarily on whether first-order factors or dimensions are considered as causes or as indicators of second-order factors. If a change in one of the dimensions necessarily results in similar changes in other dimensions, then a molecular model is suitable. Otherwise, a molar model is the most appropriate choice (Chin and Gopal, 1995). In our study, organizational ambidexterity is modeled as a molar second-order factor, since this construct is conceptualized as a composite of its multiple dimensions (exploitation and exploration) (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004). As Podsakoff et al. (2006) explain, unless this approach is adopted, the higher-order construct (ambidexterity) fails to capture the total variance in its dimensions (exploration and exploitation) and will reflect only the variance that is common to its dimensions.

Organizational structure characteristics. Differentiation was estimated from three items related to the degree of vertical and horizontal differentiation (Burton and Obel, 2005) (Table 1). The measure of centralization was adapted from Miller and Dröge (1986). We used six decisions that a firm must often make (Table 1). Respondents had to indicate the hierarchical level at which each of these decisions is made, in a seven-point scale that ranged from 1 (base-level workers, or low centralization) to 7 (the owners, or high centralization). In the case of formalization, following Adler and Borys (1996), we distinguished two more variables: one related to the existence of procedure regulations and job descriptions (enabling formalization), while the other referred to the enforcement and control of compliance with such regulations and descriptions (coercive formalization). The former was measured with a six-item seven-point scale adapted from Miller (1992) and also used in Pelham and Wilson (1996) and the latter with a four-item seven-point scale adapted from Jansen et al. (2006) (see Table 1).

Environmental dynamism. Environmental dynamism was estimated from 5 items about technological changes, change in products, in distribution and supplier activities (Table 1). The studies of Lee and Miller (1996) and Miller and Dröge (1986) were used for this variable.

Firm performance. As this work analyzes firms from a number of sectors, we decided to employ the subjective approach to measuring performance (Akan et al., 2006; Cao et al., 2009; Spanos and Lioukas, 2001; White et al., 2003). Some studies defend the adequacy of subjective measures as opposed to objective ones when the study is multisectorial (Lukas et al., 2001; Powell and Dent-Micallef, 1997; Venkatraman and Ramanujam, 1986). Objective measures may show differences in firm performance that are due solely to the industry. Moreover, accounting measures are criticized for being subject to varying accounting conventions (Powell, 1992). Using the works of Govindarajan (1988), Lee and Miller (1996) and Pelham and Wilson (1996), firm performance was evaluated using six items (see Table 1), using a seven-point scale to assess the firm's performance in comparison to its main known competitors over the previous three years.

Control variables. Firm age, size, industry and environmental dynamism were used as control variables in order to eliminate their effects on firm performance (Lubatkin et al., 2006; Spanos and Lioukas, 2001; White et al., 2003). Firm age was measured by the natural logarithm of the number of years since the firm's founding, and firm size by the natural logarithm of the number of employees. Because a multisectorial sample of firms was used, any possible effects from the industry were controlled for by including dummy variables in the analyses. Environmental dynamism was also used as a control variable to control for the potential impact of market conditions on firm performance (He and Wong, 2004; Mom et al., 2009).

AnalysisPartial least squares (PLS) analysis, Version 3.0 of PLSGraph (Chin, 2001), was used. PLS is a structural equation modeling tool that takes a component-based approach to the process of estimating both the measurement model (for construct validation) and the structural model (to answer the research questions) (Bock et al., 2005; Chin et al., 2003). One characteristic of PLS is that it enables to represent both formative and reflective latent variables (Podsakoff et al., 2006). In the formative specification, the latent construct is viewed as an effect rather than as a cause of indicator responses, and consequently formative indicators do not necessarily correlate with one another; each indicator may occur independently of the others (Podsakoff et al., 2006). Therefore, traditional reliability and validity assessments are not appropriate for formative indicators (Chin, 1998b). Since PLS does not directly support second-order constructs, factor scores for first-order constructs (exploration and exploitation) were used to create ambidexterity (Bock et al., 2005; Chin et al., 2003). As a result, first-order constructs become the observed indicators of ambidexterity as a second-order factor.

ResultsAlthough the measurement and structural parameters are estimated jointly, a PLS model is analyzed and interpreted in two stages: (1) the assessment of the reliability and validity of the measurement model, and (2) the assessment of the structural model (relationships between constructs) (Barclay et al., 1995).

Measurement modelThe measurement model is assessed by examining (1) individual item reliability; (2) internal consistency; and (3) discriminant validity. These criteria should be applied only to latent constructs with reflective indicators and molecular second-order factors (i.e. second-order factors with reflective dimensions).

- (1)

Individual item reliability. In PLS, the reliability of individual items is assessed by examining the loadings of the measures with their respective construct. A rule of thumb is to accept items with loadings of 0.707 or greater. Table 1 shows loadings generally above 0.707. Some items fail to reach this level, but this is not uncommon when scales are used in causal modeling. A number of researchers believe that this rule of thumb should not be so inflexible (Chin, 1998b), since in PLS the inclusion of indicators with lower factor loadings enables to extract useful information provided by the indicator, without worsening the model fit.

- (2)

Internal consistency. Internal consistency was assessed by examining construct reliability and convergent validity. The composite reliability measure was used to assess construct reliability. In order to interpret this measure Nunnally (1978) suggests 0.7 as a benchmark for a ‘modest’ reliability applicable in the early stages of research, and a more demanding 0.8 level for basic research. All of the constructs of our study are reliable (see Table 1). They all have measures of composite reliability above 0.8, except for differentiation which is above 0.7. For convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) was examined. According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), the average variance extracted should exceed 0.5. This condition is not strictly fulfilled in all of the constructs, but values below 0.5 are actually very close to that threshold. Other studies also accepted values below 0.5 (Croteau and Bergeron, 2001; Fornell et al., 1990; Zott and Amit, 2008).

- (3)

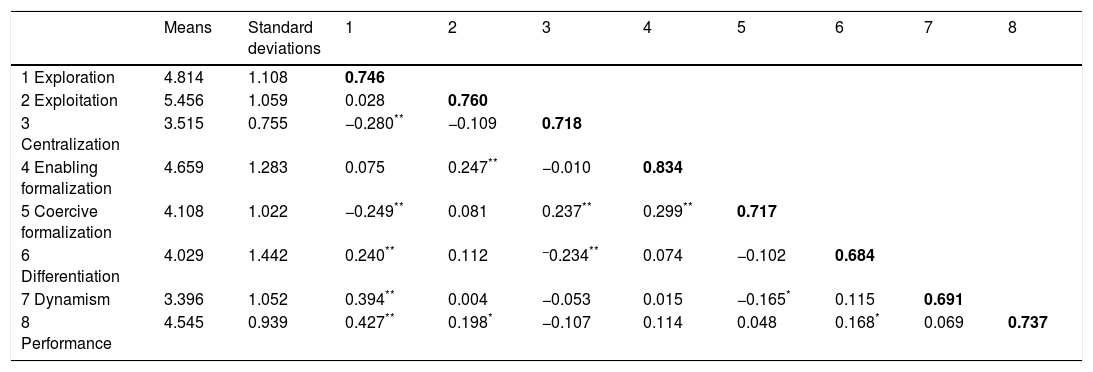

Discriminant validity. Discriminant validity refers to the extent to which one construct differs from others. When assessing discriminant validity, AVE should be greater than the variance shared between the construct and other constructs in the model (i.e. the squared correlation between two constructs) (Barclay et al., 1995). This condition is fulfilled for the reflective variables (Table 2).

Table 2.Correlation of constructs matrix.

Means Standard deviations 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 Exploration 4.814 1.108 0.746 2 Exploitation 5.456 1.059 0.028 0.760 3 Centralization 3.515 0.755 −0.280** −0.109 0.718 4 Enabling formalization 4.659 1.283 0.075 0.247** −0.010 0.834 5 Coercive formalization 4.108 1.022 −0.249** 0.081 0.237** 0.299** 0.717 6 Differentiation 4.029 1.442 0.240** 0.112 −0.234** 0.074 −0.102 0.684 7 Dynamism 3.396 1.052 0.394** 0.004 −0.053 0.015 −0.165* 0.115 0.691 8 Performance 4.545 0.939 0.427** 0.198* −0.107 0.114 0.048 0.168* 0.069 0.737 Diagonal elements in the ‘correlation of constructs’ matrix are the square roots of the average variance extracted.

For formative constructs and molar second-order factors (ambidexterity), PLS provides weights that give information about the make-up and relative importance of each item (or dimension in molar second-order constructs) (Chin, 1998b). There is a possible concern about the potential multicollinearity between formative items or dimensions (Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer, 2001). High collinearity among items may produce unstable estimates and make it difficult to single out the distinct effects of individual indicators on the construct. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was estimated to examine multicollinearity. The VIF of both exploration and exploitation was 1.001. This is far below the common cut-off threshold of 5–10 (Mason and Perreault, 1991), showing minimal collinearity.

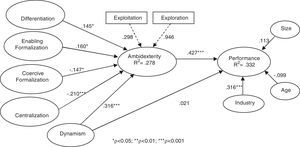

Structural modelThe assessment of the structural model entails examining the variance explained (R2) in the dependent constructs and the path coefficients (β) for the model, which indicate the relative strength of relationships between constructs. Fig. 1 shows the PLS structural model. The internal and external antecedents analyzed in this study jointly explain 28% of the ambidexterity variance (R2=0.278), and ambidexterity together with the control variables, explain 33% of the performance variance (R2=0.332).

The findings confirm our hypotheses. Regarding internal antecedents, our results show that differentiation (β=0.145, p<0.05) and enabling formalization (β=0.160, p<0.05) positively and significantly influence ambidexterity. Therefore, Hypotheses 1 and 4 are supported. Centralization (β=−0.210, p<0.001) and coercive formalization (β=−0.147, p<0.05) negatively and significantly influence ambidexterity. Then, the analysis confirms Hypotheses 2 and 3. Therefore, the organizational structure that can support the development of organizational ambidexterity seems to be a hybrid structure, with mechanistic characteristics (like differentiation and formalization) and organic characteristics (like decentralization), although we must highlight that the kind of formalization which has a positive impact on organizational ambidexterity is the enabling formalization.

Concerning external antecedents, environmental dynamism has a direct significant positive impact on ambidexterity (β=0.316, p<0.001), which confirms Hypothesis 5. Finally, in relation to consequences of ambidexterity, the analysis shows that organizational ambidexterity positively and significantly influences firm performance (β=0.427, p<0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 6 is also supported. We discuss these findings in the following section.

Discussion and conclusionsThe purpose of this study was to jointly analyze internal antecedents (differentiation, centralization and formalization) and external antecedents (environmental dynamism) together with the impact of organizational ambidexterity on firm performance. The results of our study show that firms in a dynamic environment develop ambidextrous behavior to pursue exploratory and exploitative innovations simultaneously. The more dynamic the environment of a firm, the more ambidextrous is the firm. Organizations that pursue exploitative and exploratory activities simultaneously should use several organizational characteristics. According to the findings of this study, structural differentiation, decentralization, and enabling formalization can increase both exploratory and exploitative innovations simultaneously, whereas coercive formalization negatively influences organizational ambidexterity. Moreover, organizational ambidexterity can help improve firm performance.

Previous research has focused on different approaches to analyze organizational ambidexterity (e.g. sequential, structural, contextual, or leadership approaches). This study employs two of these approaches, structural and contextual, providing empirical evidence that some organizational characteristics that are apparently contradictory (mechanistic versus organic structure), may help to pursue both exploratory and exploitative activities concurrently, and to improve firm performance.

From the structural approach, a firm can separate exploration and exploitation activities in different organizational units (differentiation), and decentralize problem solving so that each of these activities (exploration and exploitation) can be developed independently. Moreover, with formalization, the new opportunities provided by exploration may be exploited more successfully. Furthermore, formalization can help to integrate and disperse exploration and exploitation innovations across the organization. In this way, formalization may favor ambidexterity. However, from the contextual approach, formalization must be enabling and not coercive in order not to restrict exploration or exploitation activities. To that end, it is advisable that no strict monitoring or enforcement of the norms and rules created by formalization should take place, so that employees can move away from present knowledge, routines and capabilities, and experiment to create exploration and exploitation innovations. As explain Hempel et al. (2012), formalization can be considered as the banks of a river that serve as a guide for employees to move in the proper direction, but they have enough flexibility to move freely within the banks, like the river. In the same way, in a more decentralized organization, individuals may be more motivated and actively involved in interpreting, assessing, and using the available information and knowledge to pursue organizational ambidexterity.

The results of this study confirm the findings of Jansen et al. (2005, 2006, 2009). For example, the study of Jansen et al. (2005) shows that decentralization and connectedness positively influences a unit's ability to pursue exploratory and exploitative innovations simultaneously. Jansen et al. (2006) find that formalization positively influences exploitation activities and that it does not decrease exploration innovation. Jansen et al. (2009) established that ambidextrous firms should create formal cross-functional interfaces that strengthen knowledge flows between differentiated units, and formalization can be a way to do this.

Similar to the conclusions of Foss et al. (2015) study, the findings of our study show that organizational characteristics supporting exploration and exploitation are not necessarily different (mechanistic versus organic). Both exploration and exploitation may benefit from differentiation, decentralization and formalization. The findings show that a hybrid structure, with organic (decentralization) and mechanistic characteristics (differentiation and formalization) (Van Looy et al., 2005; Foss et al., 2015) may favor the development of organizational ambidexterity.

With regard to the influence of ambidexterity on firm performance, this study shows a positive effect, in line with the findings of other works (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004; He and Wong, 2004; Lubatkin et al., 2006). Thus, the simultaneous pursuit of exploration and exploitation activities can overcome the risk of rigidities and obsolescence of exploitation and, at the same time, the risk of never gaining the returns of exploration innovations.

Our study has several academic implications and contributions to current research. First, we jointly analyze antecedents and consequences of organizational ambidexterity, and both internal and external antecedents are examined. Regarding internal antecedents, as noted above, we address two approaches of ambidexterity (structural and contextual views) through several characteristics of organizational structure, and provide additional insights into pursuing contradictory ends simultaneously. The paper examines how firms are able to become ambidextrous taking into account the characteristics of organizational structure. Our results build on and extend recent studies that discuss the possibility of organizations overcoming contradictory pressures for exploitations and exploration (Stettner and Lavie, 2014) by managing seemingly contradictory characteristics of organizational structure. With regard to external antecedents, our study provides empirical evidence of the influence of environmental dynamism on organizational ambidexterity. Our work also provides empirical evidence about the positive influence of ambidexterity on firm performance. In short, we indicate new ideas with regard to the linkage between organizational structure, environmental dynamism, ambidexterity and firm performance. Second, extending previous research, we have analyzed these relationships in a different population of firms (large firms from different industries). Moreover, we measure ambidexterity in a different way, that is, as a multidimensional second-order construct consisting of two formative dimensions. We consider this measure is more appropriate to capture the total variance in its dimensions (exploration and exploitation).

Regarding managerial implications, this study emphasizes some organizational structure characteristics that managers can implement to support organizational ambidexterity. Many managers recognize and complain about the unpredictability and irregularity of their business environments. According to our findings, and like other studies (e.g. Kim and Rhee, 2009), managers and their firms should be prepared to seize the opportunity to excel at environmental changes by simultaneously developing exploration and exploitation activities. Managers must be capable of recognizing the need for ambidexterity in an organization, according to their environmental dynamism degree, and to implement appropriate organizational characteristics to develop it. They cannot manage environmental dynamism, but they can design the characteristics of their organization. In fact, the design of organizational structure is essential for many aspects of the firm, such as the implementation of strategy, and the findings of our study show that it can also be important to achieve organizational ambidexterity. Managers must be aware and use organizational structure for their own benefit as a facilitator of ambidexterity. In this regard, the more differentiated, decentralized and formalized (not coercively, but in an enabling way) the organizational structure, the more ambidextrous could be the firm, and better performance could achieve. That is, structural differentiation could be a feasible solution for achieving ambidexterity by the structural separation in different organizational units of exploration and exploitation activities. But other organizational characteristics can also favor the simultaneous development of exploration and exploitation activities. Thus, decentralization of decision-making may enhance the identification of new opportunities for exploration or exploitation, and allows organizational members to respond to the new opportunities. And enabling formalization can help individuals to solve work problems and improve their work processes and activities, thus favoring either exploitation or exploration activities. Moreover, this study provides new empirical evidence from a sample of multisectorial firms that organizational ambidexterity has a positive influence on firm performance.

This study has also some limitations. Our data are collected from self-reported assessments of CEOs. The inclusion of several relevant control variables, Harman's one-factor analysis, and the confidentiality that was assured for respondents, try to address this issue. Given the cross-sectional nature of this work, we have not been able to examine how a firm's ambidextrous orientation develops over time. Moreover, we cannot ensure causality in the analyzed relationships. Although we have tried to argue theoretically about the consideration of some variables as antecedents and consequences of ambidexterity, alternative data collection would be necessary to establish causality fully (Foss et al., 2015). Likewise, this study has analyzed large Spanish firms. Therefore, we cannot generalize the findings to other contexts of firms. Future studies may consider a longitudinal research design to assess how organizational antecedents affect exploitative and exploratory innovation over time, and also the reciprocal influence between organizational structure and ambidexterity. Another interesting idea for future research would be the analysis of possible interactions between organizational variables, examining for example whether some organizational variable influences the impact of another organizational variable on ambidexterity (e.g. is enabling formalization needed for structural differentiation to positively affect ambidexterity?). Finally, an interesting topic for future research is the analysis of the microfoundations of organizational ambidexterity, examining the role of individuals, their perceptions, their characteristics, actions and interactions in developing ambidexterity as a dynamic capability. Several studies (Birkinshaw and Gupta, 2013; Eisenhardt et al., 2010; Keller and Weibler, 2015; Laureiro-Martínez et al., 2015; Nosella et al., 2012; O’Reilly and Tushman, 2008, 2011, 2013) emphasize the relevance that such an approach may have in developing and advancing research in the ambidexterity field. At the moment, very few studies have examined this issue (Bonesso et al., 2014; Keller and Weibler, 2015).

We would like to thank the Editor, Xosé H. Vázquez and the Associate Editor, Jaime Gómez, for their suggestions. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their comments. This paper has benefited from their interesting and relevant ideas and suggestions.