This study reports visual health during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 in Spain and Portugal, focusing on eye complaints and population habits.

Material and methodsCross-sectional survey through an online email invitation to patients attending ophthalmology clinics in Spain and Portugal from September to November 2021. Around 3833 participants offered valid anonymous responses in a questionnaire.

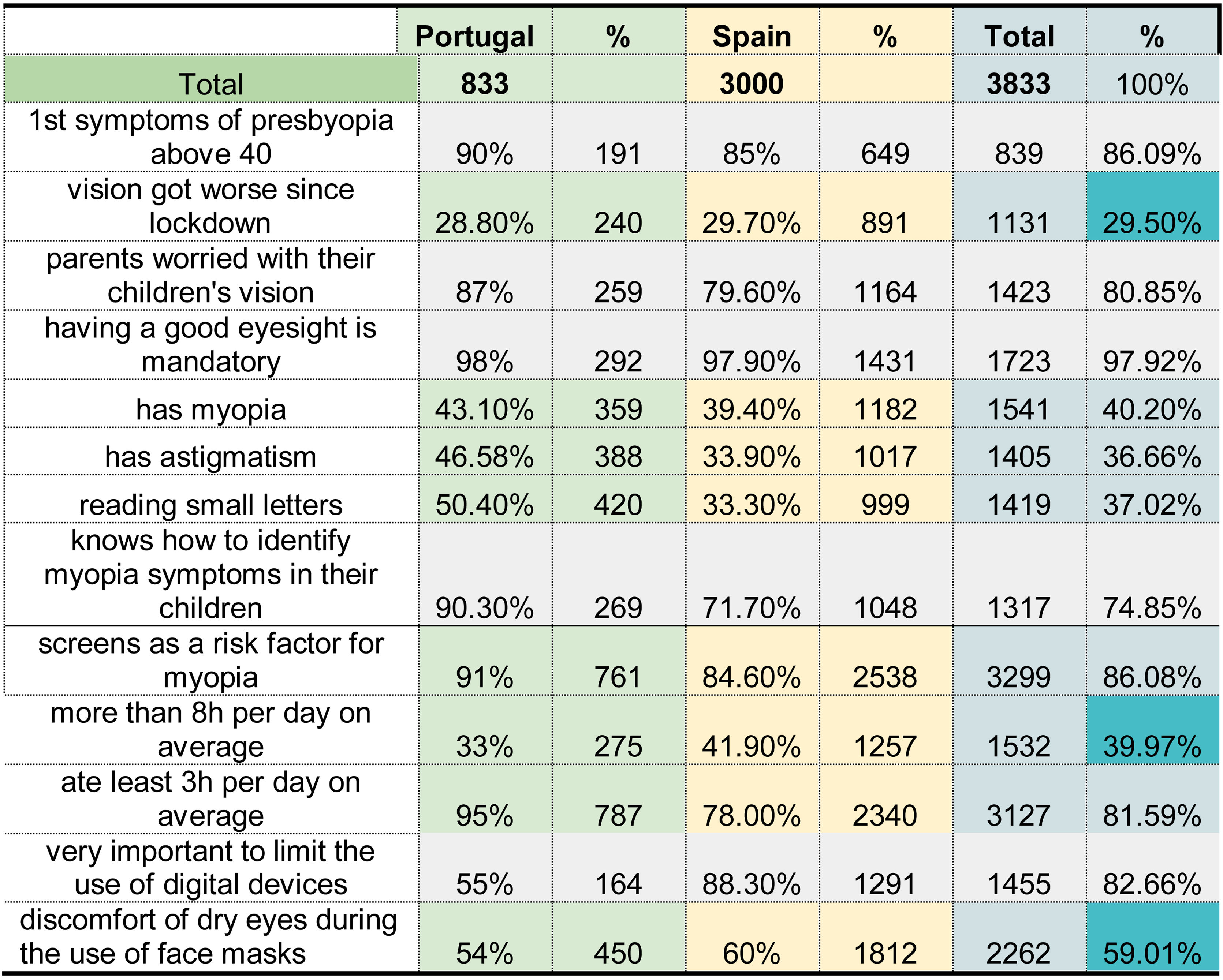

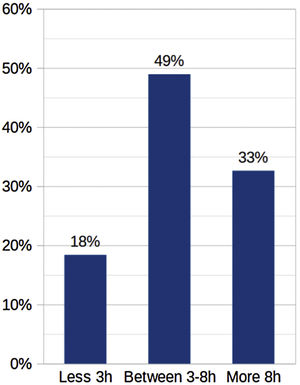

ResultsSixty percent of respondents identified significant discomfort related to dry eye symptoms for increased screen time and lens fogging using facemasks. 81.6% of the participants used digital devices for more than 3 h per day and 40% for more than 8 h. In addition, 44% of participants referred to worsening near vision. The most frequent ametropias were myopia (40.2%) and astigmatism (36.7%). Parents considered eyesight the most important aspect of their children (87.2%).

ConclusionsThe results show the challenges for eye practices during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. Focusing on signs and symptoms that lead to ophthalmologic conditions is an essential concern, especially in our digital society highly dependent on vision. At the same time, the excessive use of digital devices during this pandemic has aggravated dry eye and myopia.

Este estudio reporta los hábitos de la población y las quejas oculares relacionadas con la salud visual en el contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19 a partir de visitas realizadas durante 2021 en España y en Portugal.

Material y métodosInvitación por correo electrónico a una encuesta transversal online y también realizada en persona a pacientes de clínicas de oftalmología de España y de Portugal de septiembre a noviembre de 2021. Participaron 3.833 encuestados mayores de 18 años con respuestas anónimas válidas.

ResultadosEl 60% de los encuestados explicó mucha incomodidad causada por el aumento de los síntomas de ojo seco debido al trabajo digital más intenso y el empañamiento de los lentes al usar mascarillas. El 81,6% de los encuestados usaba dispositivos digitales al menos 3 horas en promedio por día, y el 40% comenzó a usar dispositivos digitales más de 8 horas en promedio por día. Además, el 44% de los encuestados sintió que su visión de cerca había empeorado en este período. El primer síntoma importante de la presbicia estaba relacionado con la dificultad para leer las letras más pequeñas de los paquetes. El 86% presentó los primeros síntomas a los 40 años. Las ametropías más frecuentes identificadas fueron miopía (40,2%) y astigmatismo (36,7%). Para los padres, tener buena vista (87,2%) era el aspecto más valorado en la vida de sus hijos.

ConclusionesLos hallazgos brindan una idea de los desafíos durante la COVID-19 para las prácticas oftalmológicas. En una sociedad altamente dependiente de la visión, es fundamental centrarse en los signos y los síntomas que conducen a afecciones oftalmológicas. El uso excesivo de dispositivos digitales y el uso de mascarillas durante esta pandemia han agravado algunos, señalando la importancia de la referencia para planificar una atención ocular eficiente en situaciones similares.

COVID-19 was identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 by an ophthalmologist. The disease quickly spread worldwide, resulting in the COVID-19 pandemic. Spain and Portugal declared subsequent lockdowns to limit the spread, restricting population interactions and movement. It affected working practices despite ophthalmologists being essential workers and allowed to keep eye care. The pandemic changed daily habits and visual complaints in the population, especially concerning more time in front of screens and the use of facemasks and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), having repercussions in dry eye and myopia progression.1–3

This study describes the primary care experiences of ophthalmologists during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic to better understand visual complaints, resource distribution and interests.

Material and methodsStudy designCross-sectional survey through an online email invitation to patients attending ophthalmology clinics in Spain and Portugal from September to November 2021. The study obtained ethical approval following the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The responders had to accept the participation through online informed consent at the beginning of the questionnaire.

SurveyThe questionnaire was developed by a group of experts in the field to identify areas of interest during the pandemic. The questionnaire was distributed online and available on a web platform from September to November 2021. The inclusion criteria were respondents older than 18 who received eye care during the pandemic in Spain and Portugal. The patients were referred to a secure website where they indicated their consent to participate after reading an information sheet and accepting the consent. The data was encrypted and anonymous.

AnalysisStatistical analysis was done using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) using descriptive and quantitative statistics with standard deviations.

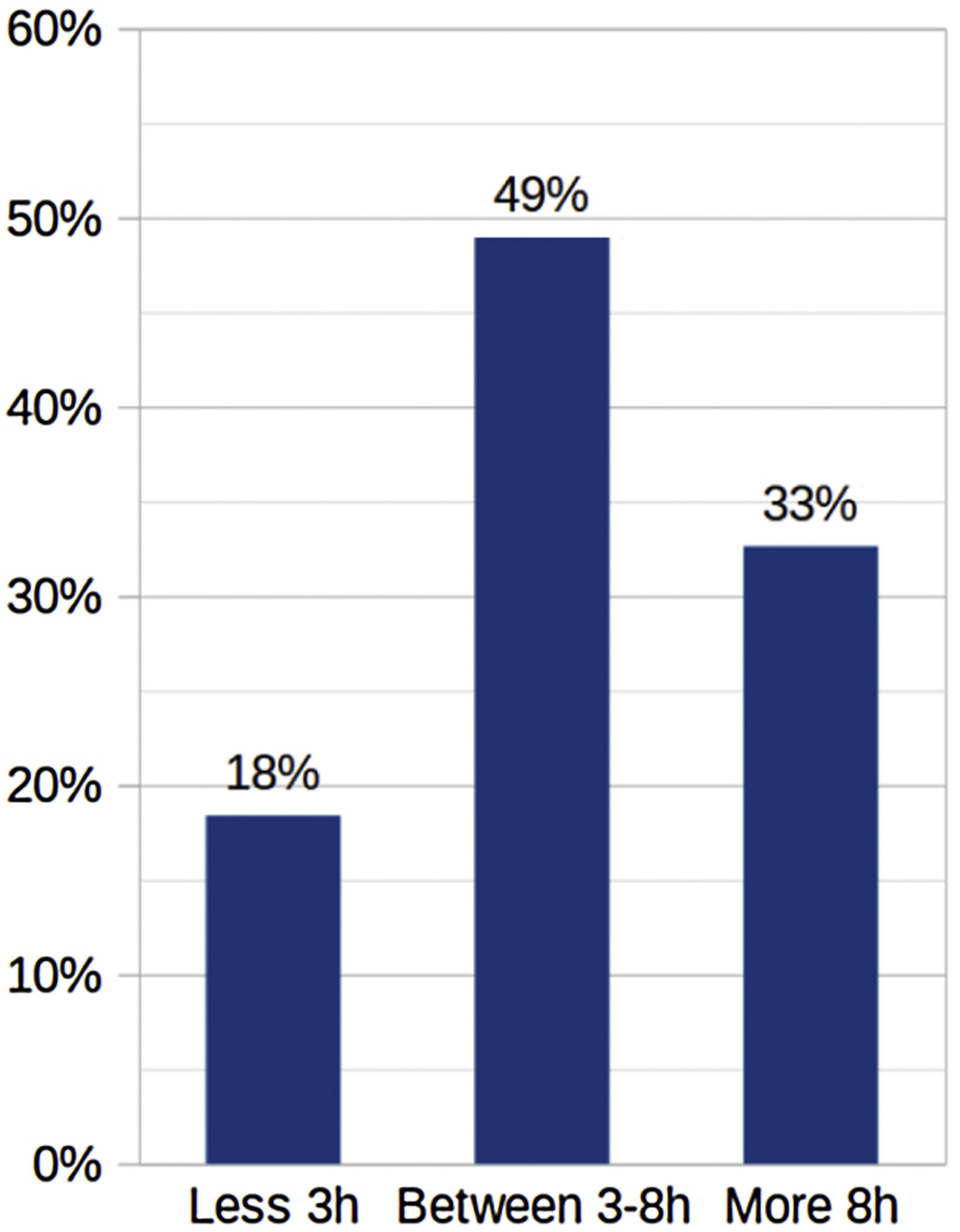

Results3833 participants completed the survey (Fig. 1), corresponding to 2081 women (54.3%) and 1752 men (45.7%). 60% referred to increasing dry eye symptoms related to more intense screen time and facemasks. 81.6% of the participants used digital devices for more than 3 h per day, and 40% for more than 8 h. In addition, 44% of participants referred to worsening near vision. The difficulty in near vision was identified as the first symptom of presbyopia in 86% of respondents. In the group, the most frequent ametropias were myopia (40.2%) and astigmatism (36.7%). After 45 years, 75% wore progressive lenses for presbyopia (Fig. 2).

The respondents that were parents considered that vision was the most important aspect of their children (87.2%) before good buccal hygiene (78.2%) or healthy diet habits (77.2%). Parents identified using digital devices as a risk factor for myopia (86%); nevertheless, only 37.8% considered limiting their use. Furthermore, parents considered that they could recognize the manifestations of myopia in their children (74.8%).

The participants checked their eyes once a year in 34.9% of cases, every 2 years in 30%, between 2 and 5 years in 17.4%, rarely 1,4%, and only when there were problems in 16.2%. The professionals of reference were ophthalmologists 61.94%, optometrists 45.62%, orthoptists 8.52%, occupational doctors 6.36%, and GPs 0.72% (multiple answers were possible).

DiscussionThe COVID pandemic and the successive lockdowns have changed our daily habits. Hence, the expansion of digital time has increased dry eye and myopia progression, impacting visual complaints.

Digital eye strain (DES) related to dry eye is associated with accommodative vision stress, decreased blinking, visual focus and other aspects like insufficient lighting, bad posture, or uncorrected refractive errors. Usually, the individual is conscious of the situation when the visual needs exceed the task. As a result, patients may complain of dryness, discomfort, blurred vision, fatigue, and headaches. Corrective measures include refraction, treating dry eye, screen time breaks and keeping a correct working distance.4,5 DES presents to some degree in 90% of screen device users6 and higher in people who use more than 4 h per day.7 DES prevalence has increased8 with the increase of digital time between 40%9 to 50%10 of cases, showing dry eye in 78% of cases.11 93.6% of subjects apprised of an increase in digital time since the pandemic, with an increase of 4.8 ± 2.8 h per day, resulting in 8.65 ± 3.74 h a day. 95.8% of participants experienced some dry eye symptoms, and 56.5% recognized an increase related to the lockdowns.12 The results of our study highlight that 81,6% of the subjects used screens for more than 3 h daily and increased dry eye symptoms to 60% during the pandemic.

Myopia development has increased for extended digital time and near work, having a lifetime impact on children. Promoting healthy habits and outdoor activities in children is essential to correct the myopigenic effects of the pandemic. The outcomes of this study extrapolate that despite 86.8% of the parents recognizing digital screens as a risk factor for myopia, only 37.8% discuss limiting their use. A strong collaboration with eye care professionals, parents and educators is vital to encourage myopia management approaches.13–19

The study has limitations for the methodology as a survey and the distribution. The online distribution limits the population representativity, and we can expect biases among the participants. In addition, our study was a symptom-based survey unrelated to the eye visit, refraction, or eye problems. The subjective patient opinion may vary the participation engagement and results. The self-perception of screen time may also differ from reality. Subjects with advanced dry eye symptomatology tend to report mild complaints, leading to underdiagnosis in self-reported questionnaires.20,21

ConclusionsOur study points out some visual complaints during the pandemic, including increased dry eye and refractive needs. In addition, this research spotlights the negative influences of screen use on dry eye and myopia progression.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.