Whereas several studies about patient falls have provided data for long-term healthcare institutions, less information is available for acute care centres. The objective was to analyze the characteristics of the patient falls and associated factors, and the effectiveness of the lower beds’ height to reduce the frequency and the harms of the patient falls in an acute geriatric hospital.

MethodsA descriptive and retrospective study using a mandatory safety incident report, the IHI Global Trigger Tool, and the claims related to patient falls between 2007 and 2011 in a 200-bed university-associated geriatric hospital.

ResultsThe falls rate was 5.4 falls per 1000 patient days (1.3% of falls led to fractures) and there was exitus in 6 patients (0.6%). Nearly half of the falls ocurred during the night shift (42.4%). By wards, falls were more frequent in acute geriatric wards (42.9%). A 7.5% of patients had a fall before admission. 3 (0.2%) claims due to possible clinical negligence were found. A reduction (28.3%) of bed falls with the lower height of the bed and a 1.88 times less falls with harm (RR 0.53; CI 95% 0.83–0.34) (p=0.006) was observed.

ConclusionThe prevention of patient falls is an important task in geriatric units with a potential reduction of harms and costs, some measures such as the lower height of the bed showed a significant reduction of the falls.

Existen estudios sobre caídas de pacientes en instituciones de larga estancia pero hay muy pocos en centros de agudos. Objetivo: analizar las características y los factores asociados de las caídas, y la efectividad de la disminución de la altura de las camas para reducir la frecuencia y los daños por caídas en un Hospital de Agudos Geriátricos.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo y retrospectivo usando un sistema de notificación de incidentes obligatorio, el Global Trigger Tool del IHI, y las reclamaciones relacionadas a caídas de pacientes entre los años 2007 y 2011 en un hospital de agudos geriátricos de 200 camas.

ResultadosLa tasa de caídas fue de 5,4 por 1000 pacientes día (1,3% produjo fracturas), con 6 exitus (0.6%). Cerca de la mitad de las caídas ocurrieron en el turno de noche (42,4%) y fueron más frecuentes en las Unidades de agudos (42,9%). Un 7,5% de los pacientes tuvo una caída previa al ingreso. Se produjeron 3 (0,2%) reclamaciones patrimoniales atribuibles a posible negligencia clínica. Las caídas de cama con la bajada de altura se han reducido un 28,3%, siendo las caídas con daño 1,88 veces menos que las ocurridas sin la bajada de la altura (RR 0,53 CI 95% 0,83–0,34) (p=0,006).

ConclusionesLa prevención de caídas de pacientes es una tarea importante en las Unidades geriátricas con una potencial reducción de costes y daños, algunas medidas como la bajada de la altura de la cama mostraron una reducción significativa de las caídas.

Falls among hospital inpatients are common, with reported rates ranging from 3 to 14 per 1000 patient days in observational and interventional studies1–3 and represent as many as 3–12 falls per month on a 25–28 bed hospital ward with maximal bed occupancy.4,5 Falls in older people occur as a result of a dynamic interaction between intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 They result synergistically from patient factors and environmental factors and are often a marker of underlying illness or change in functional status.7 Falls are associated with increased length of hospital stay8,9 and likelihood of discharge to long-term social care settings.10 Many falls are preventable and their reduction is related to a variety of interventions, either involving individual actions or changes in whole systems to minimize the risks of falls and injuries.7 The aim of this study was to determine the characteristics of the inpatient falls and associated factors in patients with and without harm, and whether the structural changes can reduce the falls in an acute geriatric hospital. Whereas several studies have provided data for long-term healthcare institutions, less information is available for acute geriatric hospitals.

Materials and methodsType of studyDescriptive and retrospective study of patient falls with the evaluation of the reduction of the bed falls before and after the reduction of the beds’ height in 2009.

SettingMonte Naranco Hospital (Oviedo, Spain), a 200-bed University-associated hospital that mainly attends geriatric patients. Bed occupation rate was 71.4% and the average length of hospital stay was 12.1 days in the study period.

DefinitionsA fall was defined as “any unplanned descent to the floor (or any other horizontal surfaces such as a chair or table) with or without injury to the patient”. The definition included “assisted falls”, in which a caregiver saw a patient about to fall and intervened, lowering them to a bed or floor, and “therapeutic falls”, in which a patient fell down during a physical therapy session with a caregiver present specifically to catch the patient in case of a fall. The definition excluded “failures to rise”, in which a patient attempted but failed to rise from a sitting or reclining position.

A fall with harm was defined as “any fall that required more than first aid care”. This definition included falls that resulted in a laceration requiring Steri-strips, skin glue, sutures, or splinting; a more serious injury; or death. The definition excluded falls that required no intervention or only first aid care, such as limb elevation, cold compress, or bandages.11 Period of study and methodology: for a period of five years (2007–2011), we collected data from the falls register (an mandatory and administrative database in which all professionals have to declare falls). The following data were collected: (a) patient characteristics (gender, age, Barthel index, and pathology, i.e. main diagnosis of hospitalization), (b) falls by group of risk of falls, and falls in the same patient, (c) time (shift, day of the week) and place (ward and location) of the falls, (d) consequences of the falls (body location of injury, related and categories of harm), and (e) underlying conditions and medications, previous use of physical restraints and other measures and known contributory factors.

Barthel Index of activities of daily living use a scoring point for the statement that most closely corresponds to the patients current level of ability for each of 10 items: incontinent bowels and bladder, grooming, toilet use, feeding, transfer, mobility, dressing, stairs and bathing, with a maximum score of 100, i.e. range of 0–20 indicating increased disability and 80–100 maximal independent activity.

We considered night shift to be from 22.00h to 8.00h and during the weekend from 22.00h on Friday night to 8.00h on Monday. All data were anonymised and aggregated.

The Global Trigger Tool (GTT)12 as another source of information about falls and to identify any falls that had occurred before admission, with a biweekly and randomized review of 10 electronic clinical records (ECR) (SELENE, Siemens) in discharge patients. The internal hospital review was conducted by a nurse and a physician, with a previous pilot training.

The following severity categories were defined: “No harm (no harm to patient), low (requiring first aid, minor treatment or extra observation), moderate (requiring admission to hospital, surgery or a prolonged stay in hospital) and severe harm (permanent harm such as brain damage or disability) with death (where death was directly attributable to the fall)”7 and another scale adapted from NCC MERP categories (National Coordinating Council for Medication Error reporting and prevention).13

The risk of falls was established by the STRATIFY (St. Thomas Risk Assessment Tool In Falling Elderly Inpatients) scale.14 STRATIFY risk of assessment tool ranged from 0 to 5, with rating 1 for presence or 0 for absence of fall risk factors (fall as a presenting complaint, a transfer and mobility score of 3 or 4+, agitation, frequent toileting, and visual impairment). A cut-off of 3 or more was used in this study and the unknown category meant that this variable was not filled in the clinical electronic record.

The contributory factors were categorized using Vincent's scheme,15 these factors were studied by the nurse and the physician and the main factor was chosen when more than one factor was present. Through the Patient Complaint Service, claims related to falls were identified.

The data are presented descriptively, chi-square test was used for the analyses. When significance testing was used, p<0.05, it was considered significant. The period of study (2007–2011) was initiated before to establish the lower height of the beds (this measure is possible just with the new beds and it was implanted in 2009), during these years we have changed the old beds, reaching in 2011 a substitution in the 64.4% of them. For this reason, to figure out the effectiveness of this measure to avoid bed patient falls, we used the RR (incidence of falls with – 2011 – and without lower height of the beds – 2007) and the Miettinen confidence intervals (CI) 95% (CI based on the Mantel–Haenszel estimators).

To check the effectiveness of the bedrails use, data of the falls between 2007 and 2008 in the cerebrovascular accident ward (CVA ward) were compared, given that in this ward the total figures: numerator and denominator were known.

Rates for falls were reported per 1000 patient-days [(no. of falls×1000/no. of patients)/no. of patient-days] and rates for falls with harm were reported per 1000 patient-days.

For the theoretical payment of cost or damages of the falls (claims due to possible clinical negligence), we used the cost calculated by Oliver et al.16: £12,945 (mean payment) or 16,135.85 euros.

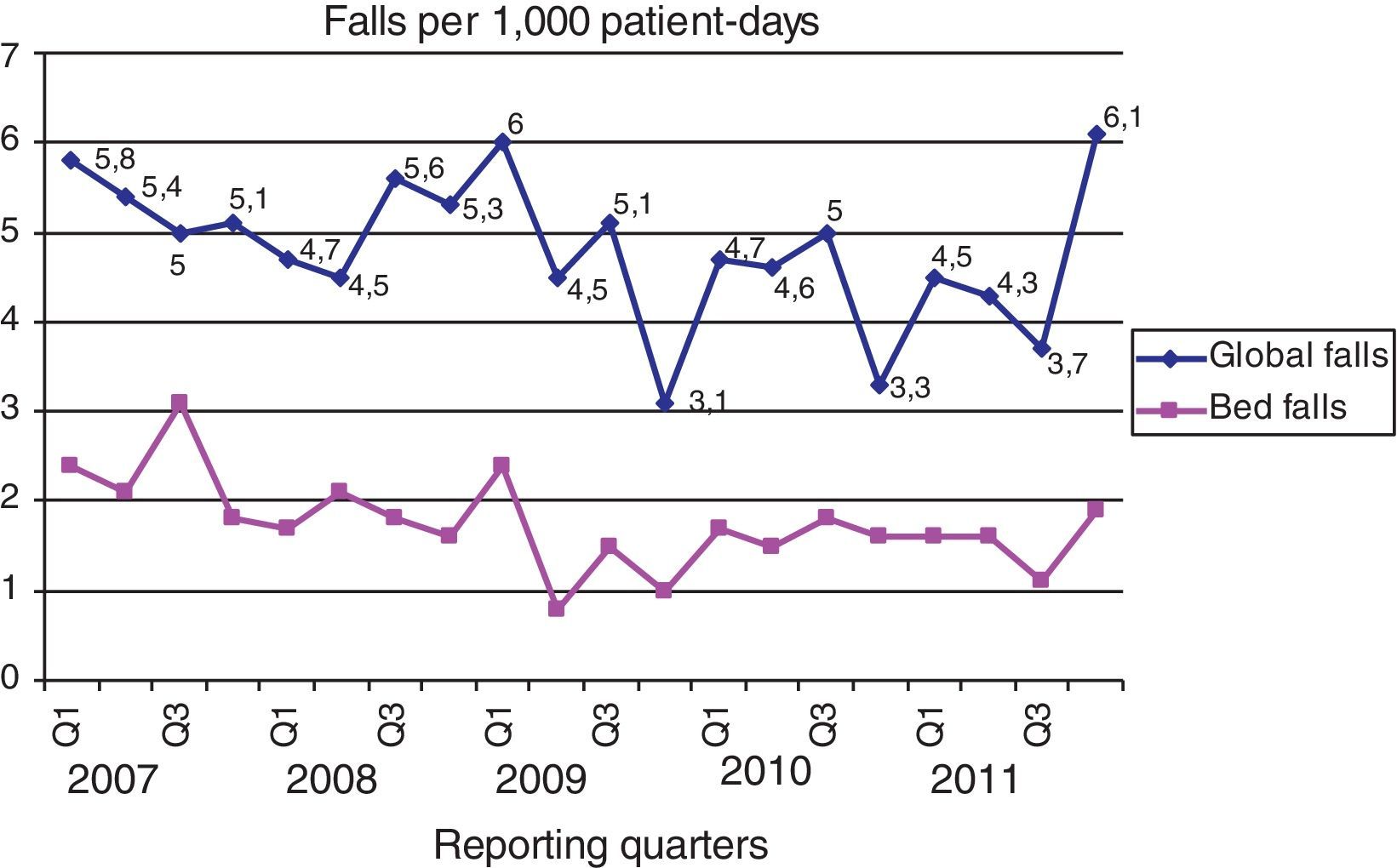

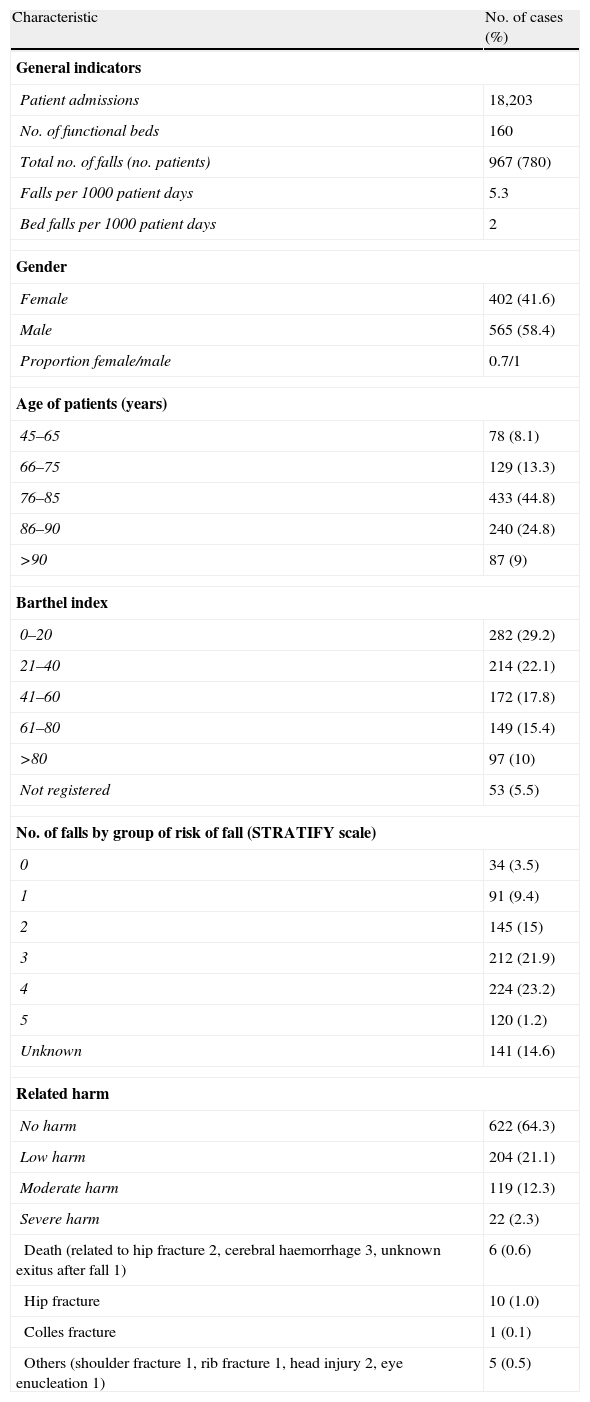

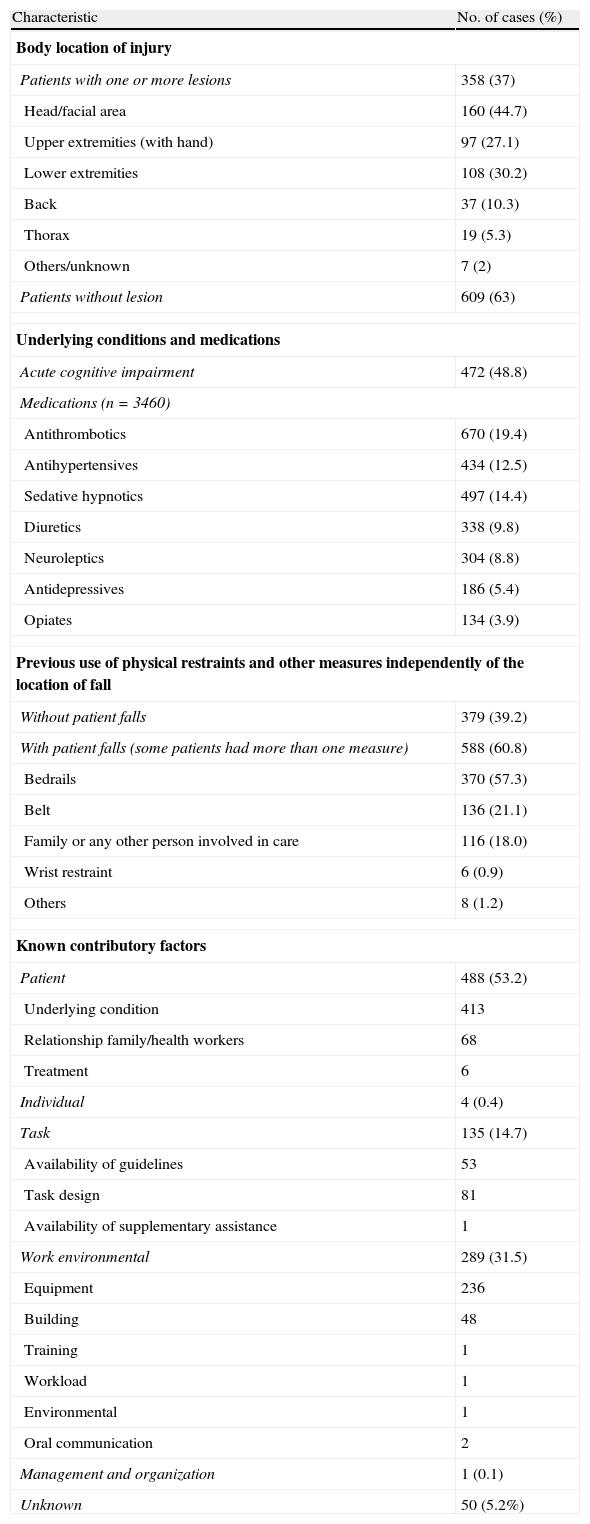

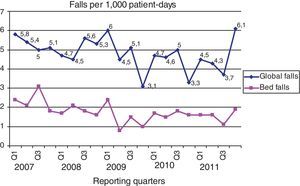

ResultsThere were 967 reports of falls in 780 patients (1.2 falls per patient) (Table 1A). The falls rate varied between 5 and 5.5 falls per 1000 patient days. Bed falls per 1000 patient days per year (2007–2011) were: 2.2, 2, 1.6, 1.9 and 1.8 respectively. The trends in global and bed falls are shown in Fig. 1.

Characteristics in relationship with patient falls (n=967).

| Characteristic | No. of cases (%) |

| General indicators | |

| Patient admissions | 18,203 |

| No. of functional beds | 160 |

| Total no. of falls (no. patients) | 967 (780) |

| Falls per 1000 patient days | 5.3 |

| Bed falls per 1000 patient days | 2 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 402 (41.6) |

| Male | 565 (58.4) |

| Proportion female/male | 0.7/1 |

| Age of patients (years) | |

| 45–65 | 78 (8.1) |

| 66–75 | 129 (13.3) |

| 76–85 | 433 (44.8) |

| 86–90 | 240 (24.8) |

| >90 | 87 (9) |

| Barthel index | |

| 0–20 | 282 (29.2) |

| 21–40 | 214 (22.1) |

| 41–60 | 172 (17.8) |

| 61–80 | 149 (15.4) |

| >80 | 97 (10) |

| Not registered | 53 (5.5) |

| No. of falls by group of risk of fall (STRATIFY scale) | |

| 0 | 34 (3.5) |

| 1 | 91 (9.4) |

| 2 | 145 (15) |

| 3 | 212 (21.9) |

| 4 | 224 (23.2) |

| 5 | 120 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 141 (14.6) |

| Related harm | |

| No harm | 622 (64.3) |

| Low harm | 204 (21.1) |

| Moderate harm | 119 (12.3) |

| Severe harm | 22 (2.3) |

| Death (related to hip fracture 2, cerebral haemorrhage 3, unknown exitus after fall 1) | 6 (0.6) |

| Hip fracture | 10 (1.0) |

| Colles fracture | 1 (0.1) |

| Others (shoulder fracture 1, rib fracture 1, head injury 2, eye enucleation 1) | 5 (0.5) |

There were 565 males with falls out of 7640 male inpatients (7.4%) versus 402 women out of 10,551 women inpatients (3.8%). This difference was statistically significant (p=0.000). A 91.9% of falls occurred in patients over 65 years, mainly in the 76–85 years range (44.8%) and 86–90 years (24.8%). A Barthel index ≤40 was present in 51.3% of the patients (Table 1A).

The main diagnoses were: neoplasia (183, 23.5%), infections (179, 22.9%), CVA (cerebrovascular accident) (153, 19.6%), cardiac diseases (119, 15.3%), traumatological conditions (118, 15.1%), respiratory diseases (52, 6.7%), chronic vascular conditions (36, 4.6%), and others (31, 4%).

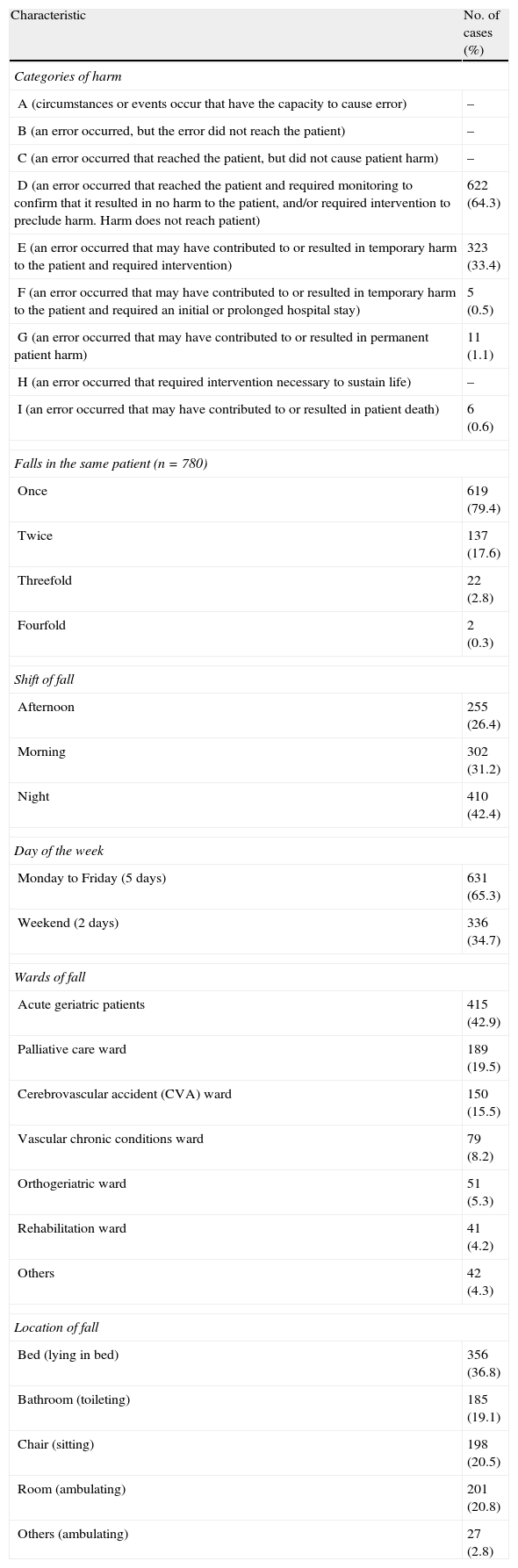

The fall rate with harm (Table 1B) (we exclude 178 patients, in the E classification of the NCC MERP categories, with contusions because they are excluded of the definition of harm) was 0.9 per 1000 patient-days (1.9 in the NCC MERP categories). There were 64.3% with no harm and 345 falls with harm (35.7%), 2.3% with severe harm (1.8% in NCCP MERP categories G–I), with 1.3% fractures (1% hip fractures) (3.8% of patients with harm, 13 out of 345) and 0.6% deaths (2 related to hip fracture, 3 to cerebral haemorrhage and 1 exitus after the fall and with unknown cause).

Characteristics in relationship with patient falls (n=967).

| Characteristic | No. of cases (%) |

| Categories of harm | |

| A (circumstances or events occur that have the capacity to cause error) | – |

| B (an error occurred, but the error did not reach the patient) | – |

| C (an error occurred that reached the patient, but did not cause patient harm) | – |

| D (an error occurred that reached the patient and required monitoring to confirm that it resulted in no harm to the patient, and/or required intervention to preclude harm. Harm does not reach patient) | 622 (64.3) |

| E (an error occurred that may have contributed to or resulted in temporary harm to the patient and required intervention) | 323 (33.4) |

| F (an error occurred that may have contributed to or resulted in temporary harm to the patient and required an initial or prolonged hospital stay) | 5 (0.5) |

| G (an error occurred that may have contributed to or resulted in permanent patient harm) | 11 (1.1) |

| H (an error occurred that required intervention necessary to sustain life) | – |

| I (an error occurred that may have contributed to or resulted in patient death) | 6 (0.6) |

| Falls in the same patient (n=780) | |

| Once | 619 (79.4) |

| Twice | 137 (17.6) |

| Threefold | 22 (2.8) |

| Fourfold | 2 (0.3) |

| Shift of fall | |

| Afternoon | 255 (26.4) |

| Morning | 302 (31.2) |

| Night | 410 (42.4) |

| Day of the week | |

| Monday to Friday (5 days) | 631 (65.3) |

| Weekend (2 days) | 336 (34.7) |

| Wards of fall | |

| Acute geriatric patients | 415 (42.9) |

| Palliative care ward | 189 (19.5) |

| Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) ward | 150 (15.5) |

| Vascular chronic conditions ward | 79 (8.2) |

| Orthogeriatric ward | 51 (5.3) |

| Rehabilitation ward | 41 (4.2) |

| Others | 42 (4.3) |

| Location of fall | |

| Bed (lying in bed) | 356 (36.8) |

| Bathroom (toileting) | 185 (19.1) |

| Chair (sitting) | 198 (20.5) |

| Room (ambulating) | 201 (20.8) |

| Others (ambulating) | 27 (2.8) |

Nearly half the falls ocurred during the night shift (42.4%) or during the weekend (34.7%). The hourly peaks occurred in the postprandial period (14–15h) 84/967 (8.7%) and in the morning (7–8h) 76/967 (7.9%). By wards, falls were more frequent in acute geriatric wards (42.9%), followed by Palliative care (19.5%) and the CVA ward (15.5%). The head/facial area (44.7%) was the most frequent body location of injury followed by the lower extremities (30.2%) (Table 1B).

The number of falls was more frequent in groups 3–5 in the STRATIFY scale (46.3%) (Table 1A) (although we do not know the denominator in each group), and 20.7% of the patients had two or more falls (down from 20.2% in 2007 to 12.5% in 2011), there was no statistically significant difference (p=0.15).

To detect patient falls in outpatients we used the Global Trigger Tool in 1200 electronic records (240 per year), we found 87 falls (7.5%), 72 in hospital inpatients and 14 (16.1%) in patients before admission: 11 (78.6%) at home, 2 (14.3%) in long-term facilities and 1 (7.1%) in another hospital.

48.8% had an acute cognitive impairment but there was no statistically significant difference between the severity of falls with (8/420 in G–I categories) and without (9/485) acute cognitive impairment (p=0.96).

The majority of the patients (97.5%) who fell were receiving medication that could contribute to the risk of falls (Table 1C).

Characteristics in relationship with patient falls (n=967).

| Characteristic | No. of cases (%) |

| Body location of injury | |

| Patients with one or more lesions | 358 (37) |

| Head/facial area | 160 (44.7) |

| Upper extremities (with hand) | 97 (27.1) |

| Lower extremities | 108 (30.2) |

| Back | 37 (10.3) |

| Thorax | 19 (5.3) |

| Others/unknown | 7 (2) |

| Patients without lesion | 609 (63) |

| Underlying conditions and medications | |

| Acute cognitive impairment | 472 (48.8) |

| Medications (n=3460) | |

| Antithrombotics | 670 (19.4) |

| Antihypertensives | 434 (12.5) |

| Sedative hypnotics | 497 (14.4) |

| Diuretics | 338 (9.8) |

| Neuroleptics | 304 (8.8) |

| Antidepressives | 186 (5.4) |

| Opiates | 134 (3.9) |

| Previous use of physical restraints and other measures independently of the location of fall | |

| Without patient falls | 379 (39.2) |

| With patient falls (some patients had more than one measure) | 588 (60.8) |

| Bedrails | 370 (57.3) |

| Belt | 136 (21.1) |

| Family or any other person involved in care | 116 (18.0) |

| Wrist restraint | 6 (0.9) |

| Others | 8 (1.2) |

| Known contributory factors | |

| Patient | 488 (53.2) |

| Underlying condition | 413 |

| Relationship family/health workers | 68 |

| Treatment | 6 |

| Individual | 4 (0.4) |

| Task | 135 (14.7) |

| Availability of guidelines | 53 |

| Task design | 81 |

| Availability of supplementary assistance | 1 |

| Work environmental | 289 (31.5) |

| Equipment | 236 |

| Building | 48 |

| Training | 1 |

| Workload | 1 |

| Environmental | 1 |

| Oral communication | 2 |

| Management and organization | 1 (0.1) |

| Unknown | 50 (5.2%) |

Physical restraints and other measures were used in 60.8% of the patients (Table 1C). In order to check the effectiveness of the bedrails in the CVA ward, because we knew the total data (numerator and denominator) and with 481 CVA patients, a statistical comparison in 2007 and 2008 was made between 427 patients with bedrails (53 with and 374 without bed falls) and 54 patients without bedrails (5 with and 49 without bed falls). In fact, no significant statistical difference was found between the two with/without bedrail proportions (RR not significant) (p=0.48). In 2007 and 2008 the mean of the level of bedrail use in the CVA ward was 88.5% but we have no data for the other wards.

The falls rate declined between 2007 and 2011 for global falls (1.33 times less frequent) (RR 0.75, CI 95% 0.91–0.62) (p=0.013) and for bed falls (1.41 times less frequent) (RR 0.71, CI 95% 0.98–0.52) (p=0.035), a reduction of 28.3%, with the lower height of the new beds (48.5cm). The rate falls with harm declined between 2007 and 2011 (1.88 times less frequent) (RR 0.53, CI 95% 0.83–0.34) (p=0.006), a reduction of 26%. In order to check whether these differences were truly significant, a statistical comparison in 2007 and 2011 was made: (a) the rate of bed falls between 2007 (12/463) and 2011 (13/423), in the Palliative care ward (without new beds in all period of study), had no statistically significance (p=0.67); and (b) the rate of bed falls between 2007 (36/904) and 2011 (12/865), in one of the two acute geriatric wards with old beds in 2007 and all new beds in 2011, had statistically significance (3.56 times less frequent) (RR 0.28 CI 95% 0.60–0.13) (p=0.001).

The Vincent's contributory factors were known in 917 patients, and the underlying condition was the main factor in 45% of the patients (Table 1C).

Through the Patient Complaint Service, during the period from 2007 to 2011, we found 9 fall complaints among a total of 1513 (0.6%). Only 3 (0.2%) were claims due to possible clinical negligence. In our study we had a theoretical global cost of 48,407.6 euros in negligence claims.

DiscussionThe dimension of the fall problem is reviewed in depth in reference.17 In Southeastern Pennsylvania patient falls accounted for 16% of all reported events and 15% of all serious events, including 16 patient deaths statewide.18 In UK patients, falls represent 60% of all reported incidents.1 We found the same frequency of falls per 1000 patient days as described in the literature for similar groups of patients. Previous work has suggested that falls are frequently under-recorded in hospitals8,9 and it is unclear that the percentages of non-injurious falls are recorded in routine nursing practice.4

Although, in the literature, the reported number of falls is higher in females,19,20 this is an artefact because in older patients the proportion of women is higher. Actually, in our study we found a higher proportion of falls among male patients than among female patients.

With the mandatory patient safety reporting, 64.3% of falls with no resulting harm were found in our study. Between 3 and 20% of inpatients fall at least once during their hospital stay in Southeastern Pennsylvania21; in our hospital the percentage was 4.3%.

The number of patients with cognitive impairment was 472 (48.8%) and the distribution of falls between the different categories of harm was similar in patients with and without acute cognitive impairment.

Around 30% of falls in hospital lead to recorded injury,1,19 and in our hospital these represent 35.7% of falls (in the E–I categories) or 15.8% with the definition of fall with harm (excluding the 178 patients with only contusions). In the falls associated with harm in patients for ages 66 or older was a 4% increase in comparison to 1% in patients for ages less than 44, or 2% for 45–65 ages,11 in our patients we did not found this difference between patients with 45–65 years (29 out of 49) (37.2%) and for ages 66 or older (333 out of 556) (37.5%). This result means that the risk is similar in all ages in our hospital and a previous study, conducted in a medium-stay hospital,22 the age and the cognitive situation were not significant variables.22

For the patient, consequences include fracture, soft tissue or head injury, fear of falling, anxiety, and depression.1,23–26 It is estimated that 1–3% of falls in hospital lead to fractures,16 1.3% in our patients (3.8% in patients with harm), a percentage which is in line with other studies.3,27 Hip fracture has a particularly devastating impact, with a mortality of 30% at 12 months for patients over 75.28 In our period of study, there were 10 hip fractures (1% of patient falls) and two of these fractures resulted in dead (20%). Six patients died in the five year period of study: 2 related to hip fracture (33.3%), 3 to cerebral haemorrhage (50%) and 1 exitus after the fall and with unknown cause (16.7%). The outcome in the rest of injured patients in the long term is not known, but since health problems or deaths arising from falls in hospital are frequently not associated with the initial fall unless they occur shortly afterwards, the health costs that they produce are probably underestimated.

Medication-induced falls accounted for 3% of the reported falls and the most common medications included benzodiazepines, opiates, antipsychotics, and cardiac medications.11 In our study, the 97.5% of the patients who fell were receiving medication and the high prevalence of falls in the Palliative care ward could be in relationship with the medication. In relationship with medication, a possible measure could be the medication's check in these patients as a prevention fall strategy.

The health-related costs of a fall are high. Reduction in quality of life and physical activity often lead to social isolation and functional deterioration, with a high risk of resultant dependency, institutionalization and death.29,30 It has been estimated that the cost of falls accounts for 3% of the total NHS expenditure.31

Another source of information about falls was the litigation registered in the Patient Complaint Service. A total of 3 claims (0.2%) were identified (mean: 12,945 sterling pounds or 16,135.85 euros per claim), higher than in the UK, where clinical negligence claims involving falls represent 0.019% of the total number of claims.16

We had a theoretical global cost of 48,407.6 euros in negligence claims, but in the rest of the patients, the nursing and medical care and the longer hospital stay increased the costs of falls and are not known.

There has been extensive literature concerning primary and secondary fall prevention strategies for older adults but these interventions were heterogeneous, and with a variability in the study design and the nature of the interventions.4,17 Protocols were improved, we used the risk scale, and we bought material resources but these interventions did not result in a better level of prevention, although the number of bed falls (with the lower height of the bed) decreased in the last year respect to the first year (1.41 times less frequent). There is no evidence that hospital falls can be consistently and effectively prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines and no interventions have yet been shown to reduce the risk of serious injury.21 Furthermore, at best, about 20% of hospital falls can be prevented.1 In our study, and with a 64.4% of new beds in all hospital in this moment, the lower height of the beds diminished the bed falls in at least a 28.3% in association with other measures. The “bundled” elements to the prevention programmes includes the following: (a) establishment of a multidisciplinary team focused on falls, (b) review and analysis of falls data, (c) performance of fall risk assessment on admission and reassessment at prescribed intervals, (d) use of visual cues to communicate falls risk, (e) use of bed-exit alarms, (f) implementation of one-to-one observation or sitter, (g) enforcement of patient rounding and (h) promotion of patient education.11 Despite hospitals’ ongoing efforts, falls continue to occur and pose a difficult challenge11 and this is an important topic in our hospital, the lower height of the beds is an important measure to avoid the bed falls that is shown in our data.

There are potential methodological limitations in our study because there are unknown data for some patients that do not permit correlation of fall incidents with the patient's length of stay. An interventional study design seems to be more convenient than our study, a descriptive study with different modifications such as the type of bed or bedrails or biases such as the information of the falls. However this is the real situation in our hospitals and the implementation of measures such as acquiring new beds represents an important imbursement cost for the hospital. Our study has implications for clinical practice in this hospital. We have investigated the scale of the falls’ problems in order to improve fall prevention at hospital level: since 2006 we have bought new beds and chairs, and we have rebuilt the bathrooms in some wards in order to avoid falls. We worked on a fall procedure and tried to identify the patient who is prone to fall in the hospital but unfortunately the STRATIFY scale is not validated in other studies. Otherwise, we cannot establish the relative frequency of falls in each group of the STRATIFY scale because we do not know the total number of patients in those groups. Although the role of bedrails in falls prevention is controversial,32,33 serious direct injury from bedrails is usually related to the use of outmoded designs and incorrect assembly rather than being inherent to their use per se and bedrails do not appear to increase the risk of falls or injury from falls.34 The comparison between patients with and without falls and bedrails in the CVA ward showed that there is not statistical significance. Maybe outmoded beds and the type of patients or other unknown factors are important in the differences found in several studies. The number of bed falls was significantly lower after the lower height of beds and with not significant reduction in the Palliative ward (where we had old beds in all period of study), however we have not enough information to check whether the reduction is exclusively due to the lower height of beds or other unknown factors such as changes in the staff, type of inpatients, etc. that could be an added factors to the reduction of bed falls.

In summary, we have shown the trends in patient falls, the prevention of falls (which turns out to be a difficult task) and the lessons learned during these years with the lower height of the beds.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors thank Nicholas Airey, BSc, for English language corrections, and all health workers in our hospital for their collaboration in the prevention of falls.