Interstitial Lung Disease Associated with Autoimmune Diseases

Más datosInterstitial lung disease is a common complication of Sjögren's syndrome that can occur at diagnosis or during follow-up. To detect it, complete pulmonary function studies should be performed, including spirometry, measurement of lung volumes, and DLCO, with the latter being the most sensitive parameter for detecting the presence of the disease. High-resolution computed tomography is essential for the study. Sixty percent of patients present a single tomographic pattern, with non-specific interstitial pneumonia being the most frequent pattern, followed by usual interstitial pneumonia pattern. Mortality is high, being higher in those with lower forced vital capacity, lower DLCO, and higher fibrosis score on chest computed tomography. Currently, there are two international guidelines for the treatment of pulmonary manifestations of Sjögren, but recommendations are based on low-quality scientific evidence. A stepwise approach is suggested, initially with glucocorticoids, then immunosuppressants, and in refractory or severe cases, considering other agents such as rituximab. The use of antifibrotic medication is recommended in patients who develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis as defined by current criteria. It is important to bear in mind that although non-specific interstitial pneumonia is considered a pattern where inflammation predominates, there may be progression to progressive pulmonary fibrosis in some cases. Lung transplantation and oxygen therapy may be options for selected patients. The relevance of an interdisciplinary team approach to achieve adequate diagnosis and treatment of patients is highlighted.

La enfermedad pulmonar intersticial es una complicación común del síndrome de Sjögren, la cual puede aparecer al diagnóstico o durante el seguimiento de dicho síndrome. Para detectarla es necesario llevar a cabo estudios de función pulmonar completos, que incluyan espirometría, medición de volúmenes pulmonares y prueba de difusión de monóxido de carbono (DLCO, por su abreviatura en inglés), siendo este último el parámetro más sensible para detectar la presencia de la enfermedad. La tomografía computarizada de alta resolución es esencial para el estudio. El 60% de los pacientes presentan un único patrón tomográfico; el patrón de neumonía intersticial no específica es el más frecuente, seguido por el patrón de neumonía intersticial usual. La mortalidad es elevada, siendo mayor en aquellos con menor capacidad vital forzada, menor DLCO y mayor score de fibrosis en la tomografía computarizada de tórax. En la actualidad, hay 2 guías internacionales para el tratamiento de las manifestaciones pulmonares del Sjögren, pero las recomendaciones se basan en evidencia científica de baja calidad. Se sugiere un abordaje escalonado, inicialmente con corticoides, luego inmunosupresores y en casos refractarios o severos es preciso considerar otros agentes como el rituximab. El uso de medicación antifibrótica se recomienda en los pacientes que tengan una evolución con criterios de fibrosis pulmonar progresiva. Es importante considerar que, aun cuando la neumonía intersticial no específica se considera un patrón donde predomina la inflamación, en algunos casos puede haber progresión a fibrosis pulmonar progresiva. El trasplante de pulmón y la oxigenoterapia pueden ser opciones para pacientes seleccionados. Se destaca la relevancia de contar con un enfoque de equipo interdisciplinario para lograr un diagnóstico y un tratamiento adecuados para los pacientes.

Primary Sjögren's syndrome (SS) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands.1 Most patients present with dysfunction of salivary and lacrimal glands, with xerophthalmia and xerostomia as typical symptoms at the onset of the disease. Many patients can also develop a wide variety of systemic extraglandular manifestations, which may even be the initial manifestation of the disease.2

Various forms of lung involvement have been reported in patients with SS, such as bilateral pleural effusion, pulmonary infections, pulmonary embolism, drug toxicity, airway involvement with xerotraquea, bronchiectasis and bronchiolitis, interstitial lung disease (ILD), pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary amyloidosis or B-cell lymphoproliferative disease, especially non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.3–10 Sjögren syndrome-associated interstitial lung disease (SS-ILD) is a frequent complication that determines a lower quality of life for patients and greater mortality.11–14

The objective of this article is to perform a bibliographic review of SS-ILD, its epidemiology, risk factors, complementary diagnostic studies and therapeutic strategies oriented to this disease.

EpidemiologyThe frequency of occurrence of SS-ILD varies in different studies depending on the method used for detection. In many studies of SS, systemic extraglandular manifestations are evaluated following the parameters of the European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI), which evaluates constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy, glandular involvement, joint, skin, renal, and pulmonary involvement, among others.15 Pulmonary involvement according to ESSDAI should be evaluated taking into account respiratory symptoms, findings on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), and respiratory function measured by spirometry and diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO).16 In a multi-ethnic, multicenter, international cohort like the Big Data Sjögren Consortium, pulmonary involvement measured by ESSDAI is reported to be 12%. In a retrospective study of 333 patients with SS who underwent HRCT at the time of SS diagnosis, SS-ILD was detected in 19.8% of patients.17–19

Various risk factors for the development of SS-ILD have been reported. Age appears to be one of the most important. SS-ILD is usually detected near the sixth decade.18 Other risk factors for the development of ILD in patients with SS include male sex, previous smoking, longer duration of disease, onset of Sjögren without sicca symptoms, greater inflammation on minor salivary gland biopsy, presence of Raynaud's phenomenon, higher levels of ANA, rheumatoid factor, Anti-Ro-52, and C-reactive protein.17,19–21

Screening for ILD in patients with Sjögren syndromeThe timing of ILD manifestation in SS is variable. It may occur at diagnosis or during follow-up, and in some cases, ILD may be the first manifestation of the disease.17,22,23 Clear guidelines or consensus on the type of complementary studies to be used for screening pulmonary involvement in SS patients without respiratory symptoms do not yet exist. In SS patients without respiratory symptoms, it is suggested to repeat respiratory function studies and computed tomography based on the treating physician's clinical judgment and in case of onset or worsening of respiratory symptoms.24–26

Detection of occult SS in patients with ILD with autoimmune featuresIn the initial examination of a patient with ILD, autoimmune diseases that may be responsible for the disease should be ruled out.27 SS may initially present with non-sicca (systemic) manifestations. When these features appear before the onset of an overt sicca syndrome, we may talk of an underlying ‘occult’ SS. Furthermore, some patients with ILD have clinical or serological manifestations of autoimmunity but do not meet classification criteria to define a connective tissue disease. These patients have been grouped under the term IPAF (interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features). In 2015, a Research Statement on IPAF was published, emphasizing the importance of certain clinical, serological, pathological, and HRCT findings to suspect autoimmunity in patients with ILD. However, this statement was published before the 2016 SS classification criteria and only suggested testing for Anti-Ro and Anti-La antibodies, without mentioning the other classification criteria such as minor salivary gland biopsy, Schirmer's test, ocular staining score, and sialometry. These should be requested by the rheumatologist after a thorough clinical evaluation.1,28 In subsequent studies, it was observed that in patients with ILD and clinical or serological signs of autoimmunity, a significant percentage of them can be classified as SS, if SS classification criteria are sought thoroughly.29–32

SymptomatologyThe most common symptoms in patients with SS-ILD are dry cough, cough with sputum production, exertional dyspnea, chest tightness, and recurrent pulmonary infections.17

Diagnostic testsPulmonary function testsTo detect ILD, a complete pulmonary function test (PFT) should be requested, which includes spirometry, measurement of lung volumes, and DLCO. DLCO measurement is often one of the most sensitive parameters for detecting the presence of ILD, while the use of lung volumes is more useful for assessing the severity of ILD.33 Patients with SS-ILD usually have decreased values of FVC, forced expiratory volume in one second, total lung capacity, and DLCO compared to patients with SS without ILD.19 At the time of SS-ILD diagnosis, there is usually a mild restrictive defect, with decreased FVC and DLCO in most cases.18 It should be noted that there may be a discrepancy between patient symptoms, HRCT findings, and PFT in the initial study of patients with SS-ILD. Therefore, the severity of the disease cannot be assumed based on HRCT or PFT alone, as both are complementary.34–36

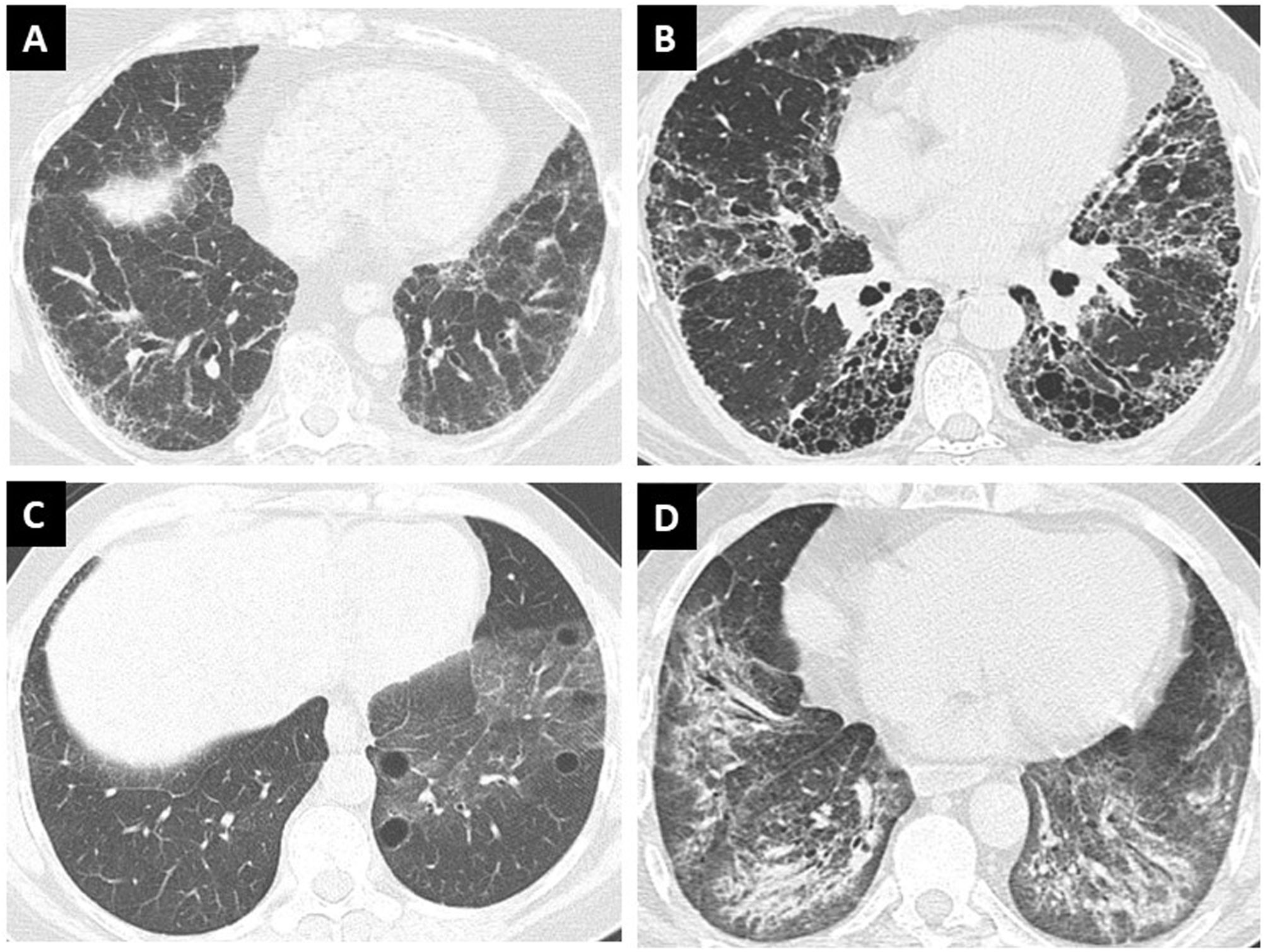

High-resolution computed tomography: ILD patterns and evolutionHRCT is essential for the study of all patients with ILD, and certain quality standards for image acquisition and processing should be required in order to visualize the greatest possible detail.27 Sixty percent of patients with SS-ILD present a single pattern of ILD, while the remaining 40% present combined patterns. The pattern of non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) is the most frequent (41%), followed by the pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). Organizing pneumonia (OP) and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) as a single pattern are less frequent. Within the combined patterns, the association of NSIP plus OP (Fig. 1), NSIP plus UIP, and NSIP plus LIP are usually found.19,37 Although NSIP is considered a pattern where inflammation predominates, the component of traction bronchiectasis, interlobular septal thickening, and honeycombing cysts that are often present should be taken into account and monitored for their progression over time. Up to 20% of cases of NSIP with inflammatory predominance evolve into fibrotic NSIP over time.38

Patterns of high-resolution computed tomography of the chest in interstitial lung disease in Sjögren Syndrome. (A) Non-specific interstitial pneumonia, (B) usual interstitial pneumonia, (C) lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, and (D) combined pattern of non-specific interstitial pneumonia associated with organizing pneumonia.

Findings in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid obtained from patients with SS-ILD are often abnormal, showing in most cases a lymphocytosis, mainly characterized by T-cells, even among asymptomatic patients.39 However, abnormalities in the cellular constituents of the BAL fluid are not useful for predicting outcome or treatment response. As a result, BAL is not routinely performed in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with SS-ILD. In patients with an acute onset or worsening of respiratory symptoms and radiographic abnormalities, BAL is useful for excluding malignancy or infection.40

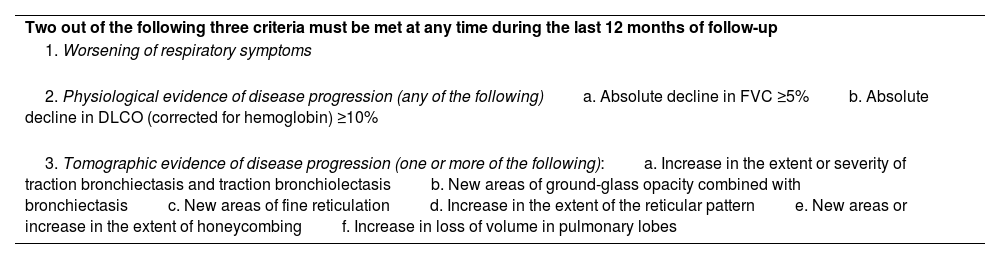

Evolution of SS-ILDIn the follow-up of patients with SS-ILD, the patient should be stratified at the initial evaluation based on the tomographic extent of ILD, initial involvement of FVC and DLCO, and the severity of symptoms attributed to lung disease. Furthermore, the patient should be re-stratified every 4–6 months to determine if there is progression in respiratory function tests or symptoms. In some cases, SS-ILD may present with an acute exacerbation of the disease, characterized by a rapid decline in pulmonary function and worsening respiratory symptoms, associated with high mortality.41 During follow-up, it is important to assess whether the criteria for defining progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) are met, as this clinical behavior is associated with high morbidity and mortality (Table 1).27 Although specific prospective studies of SS are lacking, it is estimated that around 24–38% of patients with SS-ILD will develop PPF during the course of the disease.42–44

Definition of progressive pulmonary fibrosis.

| Two out of the following three criteria must be met at any time during the last 12 months of follow-up |

| 1. Worsening of respiratory symptoms |

| 2. Physiological evidence of disease progression (any of the following)a. Absolute decline in FVC ≥5%b. Absolute decline in DLCO (corrected for hemoglobin) ≥10% |

| 3. Tomographic evidence of disease progression (one or more of the following):a. Increase in the extent or severity of traction bronchiectasis and traction bronchiolectasisb. New areas of ground-glass opacity combined with bronchiectasisc. New areas of fine reticulationd. Increase in the extent of the reticular patterne. New areas or increase in the extent of honeycombingf. Increase in loss of volume in pulmonary lobes |

FVC: forced vital capacity; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide.

The pattern of NSIP has been classically associated with the progression of SS-ILD and the development of PPF. In addition, other factors for progression of SS-ILD have been reported, such as older age at disease onset, onset of SS without sicca symptoms, greater reticulation component on computed tomography, and extensive pulmonary involvement.13,38,44,45

MortalityMortality data in SS-ILD are variable depending on the series, with a 5-year mortality rate ranging from 11 to 39%.46–48 Patients with higher mortality rates have lower forced vital capacity (FVC), lower DLCO, and a higher fibrosis score on HRCT.14

TreatmentThe treatment of patients with SS-ILD should be based on three pillars: respiratory rehabilitation, infection prevention, and pharmacological therapy.

Pulmonary rehabilitationLike in patients with idiopathic ILD or that associated with other autoimmune rheumatic diseases, pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve exercise capacity, reduce dyspnea, improve quality of life as measured by the Saint George's questionnaire, and increase in walking distance during the 6-minute walk test.49

Prevention of respiratory infectionsPneumococcal and influenza vaccinationIn general, the presence of rheumatic diseases such as SS or the use of immunomodulatory medication is associated with an increased risk of having more severe infectious diseases.50 Pneumococcal and influenza vaccination should be seriously considered for most patients with SS-ILD.51

COVID-19 vaccinationPatients with SS-ILD have a higher risk of hospitalization. In a multicenter case series of patients with various rheumatologic diseases including SS who contracted SARS-CoV-2, carried out by the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance, a multivariable analysis was performed to determine risk factors for hospitalization. In this group of patients, age over 65 years, presence of hypertension or cardiovascular disease, previous lung disease, diabetes, or renal insufficiency were associated with a higher risk of hospitalization due to SARS-CoV-2.52 Patients with SS-ILD should be recommended to receive vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 with any of the vaccines approved in their country.53

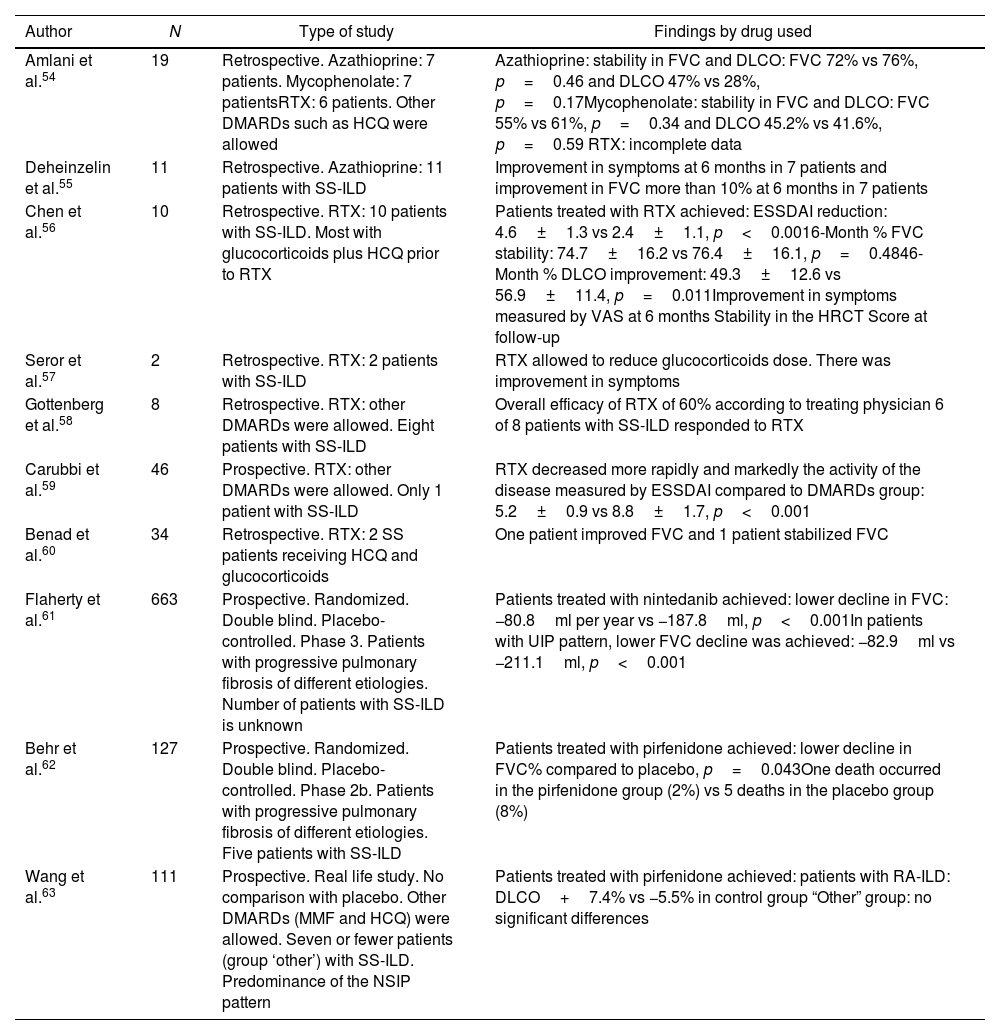

Pharmacological therapyStudies evaluating pharmacological therapy for SS-ILD have been of low quality, mostly retrospective, with a small number of patients, and without comparison with placebo (Table 2).54–63 At the time of this review, there are two international guidelines for the treatment of systemic complications of SS such as SS-ILD.

Studies with pharmacological therapy in Sjögren syndrome-associated interstitial lung disease.

| Author | N | Type of study | Findings by drug used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amlani et al.54 | 19 | Retrospective. Azathioprine: 7 patients. Mycophenolate: 7 patientsRTX: 6 patients. Other DMARDs such as HCQ were allowed | Azathioprine: stability in FVC and DLCO: FVC 72% vs 76%, p=0.46 and DLCO 47% vs 28%, p=0.17Mycophenolate: stability in FVC and DLCO: FVC 55% vs 61%, p=0.34 and DLCO 45.2% vs 41.6%, p=0.59 RTX: incomplete data |

| Deheinzelin et al.55 | 11 | Retrospective. Azathioprine: 11 patients with SS-ILD | Improvement in symptoms at 6 months in 7 patients and improvement in FVC more than 10% at 6 months in 7 patients |

| Chen et al.56 | 10 | Retrospective. RTX: 10 patients with SS-ILD. Most with glucocorticoids plus HCQ prior to RTX | Patients treated with RTX achieved: ESSDAI reduction: 4.6±1.3 vs 2.4±1.1, p<0.0016-Month % FVC stability: 74.7±16.2 vs 76.4±16.1, p=0.4846-Month % DLCO improvement: 49.3±12.6 vs 56.9±11.4, p=0.011Improvement in symptoms measured by VAS at 6 months Stability in the HRCT Score at follow-up |

| Seror et al.57 | 2 | Retrospective. RTX: 2 patients with SS-ILD | RTX allowed to reduce glucocorticoids dose. There was improvement in symptoms |

| Gottenberg et al.58 | 8 | Retrospective. RTX: other DMARDs were allowed. Eight patients with SS-ILD | Overall efficacy of RTX of 60% according to treating physician 6 of 8 patients with SS-ILD responded to RTX |

| Carubbi et al.59 | 46 | Prospective. RTX: other DMARDs were allowed. Only 1 patient with SS-ILD | RTX decreased more rapidly and markedly the activity of the disease measured by ESSDAI compared to DMARDs group: 5.2±0.9 vs 8.8±1.7, p<0.001 |

| Benad et al.60 | 34 | Retrospective. RTX: 2 SS patients receiving HCQ and glucocorticoids | One patient improved FVC and 1 patient stabilized FVC |

| Flaherty et al.61 | 663 | Prospective. Randomized. Double blind. Placebo-controlled. Phase 3. Patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis of different etiologies. Number of patients with SS-ILD is unknown | Patients treated with nintedanib achieved: lower decline in FVC: −80.8ml per year vs −187.8ml, p<0.001In patients with UIP pattern, lower FVC decline was achieved: −82.9ml vs −211.1ml, p<0.001 |

| Behr et al.62 | 127 | Prospective. Randomized. Double blind. Placebo-controlled. Phase 2b. Patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis of different etiologies. Five patients with SS-ILD | Patients treated with pirfenidone achieved: lower decline in FVC% compared to placebo, p=0.043One death occurred in the pirfenidone group (2%) vs 5 deaths in the placebo group (8%) |

| Wang et al.63 | 111 | Prospective. Real life study. No comparison with placebo. Other DMARDs (MMF and HCQ) were allowed. Seven or fewer patients (group ‘other’) with SS-ILD. Predominance of the NSIP pattern | Patients treated with pirfenidone achieved: patients with RA-ILD: DLCO+7.4% vs −5.5% in control group “Other” group: no significant differences |

SS-ILD: Sjögren syndrome-associated interstitial lung disease; FVC: forced vital capacity; DLCO: carbon monoxide diffusing capacity; RTX: rituximab; MMF: mycophenolate; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; ESSDAI: European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren Syndrome Disease Activity Index; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; DMARD: disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; NSIP: non-specific interstitial pneumonia; RA-ILD: rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease.

According to EULAR, patients with SS-ILD should always be evaluated using the ESSDAI index as it provides a more complete approach to the patient. They suggest minimizing the dose and duration of glucocorticoids use. They also mention that there is no evidence of greater effectiveness of one immunosuppressant over another, and that in patients with refractory disease, therapy targeting B cells should be used.

It is suggested to define the degree of activity of SS-ILD according to ESSDAI lung involvement:

- •

Low activity: Bronchial involvement with chronic cough without ILD on HRCT, bronchial involvement with obstructive spirometry without another cause (e.g., COPD, childhood asthma) without ILD on HRCT, subclinical or oligosymptomatic ILD on HRCT with FVC greater than 80% and DLCO greater than 70%.

- •

Moderate activity: ILD on HRCT with NYHA grade II dyspnea, with FVC between 60% and 80% and DLCO between 70% and 40%.

- •

Severe activity: ILD on HRCT with NYHA grade III or IV dyspnea, with FVC less than 60% or DLCO less than 40%.

There is uncertainty about the benefit of immunomodulatory and antifibrotic therapies that have been proposed and used for the management of SS related ILD due to the lack of reliable scientific evidence for them.

The EULAR 2019 guidelines suggest that a patient with moderate ESSDAI should receive glucocorticoids as first-line treatment. When the patient has a high ESSDAI, the first-line treatment could be oral glucocorticoids, especially in patients with LIP or OP, less so in NSIP, and much less in UIP. In these cases with high ESSDAI, a second-line treatment could be an immunomodulator as steroid-sparing agent without preference for one over the other. In cases with high ESSDAI that require rescue medication, consideration should be given to cyclophosphamide or rituximab.25

Recommendations from the CHEST 2021 guidelines for the evaluation and management of lung involvement in SSThe 2021 CHEST guidelines suggest first evaluating the severity of the condition to define the therapeutic approach. If there are no symptoms or minimal symptoms, accompanied by a respiratory function test and a computed tomography scan showing mild lung involvement, it is recommended to monitor the patient without adding pharmacological treatment. In the case of a symptomatic patient with moderate to severe lung function impairment or moderate to severe ILD in HRCT, moderate doses of oral glucocorticoids are suggested as first-line treatment, followed by second-line therapy with mycophenolate or azathioprine. If there is no satisfactory response, an evaluation of the fibrotic component of the HRCT should be performed. If there are criteria for fibrotic progression, the use of an antifibrotic could be considered. If there is clinical or functional worsening but no fibrotic progression, treatment with rituximab, calcineurin inhibitors, or cyclophosphamide could be attempted. In severe, refractory cases with rapid progression or respiratory failure, high-dose glucocorticoids should be considered, as well as the use of rituximab or cyclophosphamide. In addition, the patient should be referred for lung transplant evaluation.26 These decisions are difficult, especially in a disease with scarce and low-reliability scientific evidence. It is suggested that these decisions be made in the context of a multidisciplinary committee with the presence of expert pulmonologists, rheumatologists, and radiologists.

Use of antifibrotics in SS-ILDThe use of antifibrotics deserves a special section. The use of antifibrotics, preferably nintedanib, should be considered in cases where a patient has at least 10% fibrosis (reticular abnormalities with traction bronchiectasis, with or without honeycombing) on computed tomography and meets PPF criteria during follow-up.27 In the INBUILD study, which included patients with PPF and underlying autoimmune rheumatic disease, treatment with nintedanib resulted in a significant decrease in the decline of FVC compared to placebo, with a effect size similar to previous studies of the drug in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.61 In a similar study, the RELIEF study, pirfenidone demonstrated less decline in FVC %, compared to the placebo group.62 The 2022 international intersociety guidelines for PPF suggest considering nintedanib as a first-line treatment, emphasizing the need for further studies in specific patient populations such as those with SS-ILD with clinical behavior of PPF.27

Lung transplantationLung transplantation is an option for patients with advanced SS-ILD, although there is limited information on the outcome in patients with SS-ILD. Previously, it has been considered that patients with ILD associated with connective tissue disease, such as SS, may have a worse outcome after lung transplantation due to autoimmune dysregulation or extrapulmonary manifestations of the disease. However, in a retrospective cohort study of 275 patients, no significant differences in survival, acute or chronic rejection, or extrapulmonary organ dysfunction were found in patients with connective tissue disease who underwent lung transplantation, compared to patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.64

Oxygen therapySupplemental oxygen therapy is commonly used in managing dyspnea in patients with ILD. Dyspnea is a common symptom of ILD and can have a significant impact on the quality of life. Supplemental oxygen therapy can help improve oxygenation and reduce dyspnea in patients with ILD, especially those with advanced disease. The decision to use supplemental oxygen in patients with ILD is generally based on the severity of dyspnea and the degree of hypoxemia during exercise or at rest. In general, the use of supplemental oxygen in ILD should be individualized based on the patient's clinical status and needs. It is important to closely monitor and regularly evaluate the oxygenation status to ensure appropriate and effective use of supplemental oxygen therapy in patients with ILD.65

ConclusionsSS-ILD is a systemic manifestation of SS that occurs relatively frequently. Although there are international guidelines for the management of SS-ILD, the scientific evidence is still scarce to define with certainty the best treatment for each patient. Considering that SS-ILD can be the debut form of the disease, or manifest during follow-up, and that in some cases it marks the course of the disease, we emphasize the importance of multidisciplinary management for an adequate diagnostic and therapeutic approach to patients.

FundingThe authors received no funding for the realization of this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the realization of this article.