Interstitial Lung Disease Associated with Autoimmune Diseases

Más datosApproximately forty percent of patients with autoimmune diseases suffer from interstitial lung disease (ILD). There are currently no specific screening guidelines for these patients. ILD causes substantial morbidity and mortality; early recognition and diagnosis are essential to avoid treatment delays. The gold standard for management incorporates a multidisciplinary approach (MMD) with input from various specialties, such as pulmonary, rheumatology, radiology, and pathology, to reach a consensus regarding diagnosis and treatment. In this article, we will discuss the most common forms of ILD that affect patients with autoimmune diseases, as well as how to promptly and effectively diagnose and treat these conditions.

Aproximadamente el 40% de los pacientes con enfermedades autoinmunes padecerán enfermedad pulmonar intersticial (EPI) en algún momento del curso de su enfermedad. Desafortunadamente, no hay guías claras de cuándo evaluarlos para descartar EPI. Esta última es la primera causa de mortalidad, por lo cual diagnosticarla temprano es imperativo para evitar un retraso en el tratamiento. El estándar de oro implica un enfoque multidisciplinario con aportes de varias especialidades como neumología, reumatología, radiología y patología, para llegar a un consenso diagnóstico y de tratamiento. En este artículo discutiremos las formas más comunes de EPI que afectan a los pacientes con enfermedades autoinmunes, así como diagnosticarlas y tratarlas de manera rápida y efectiva.

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a very diverse set of non-neoplastic and non-infectious pulmonary disorders that have in common an infiltrative pathology affecting the interstitial parenchyma. These diseases are associated with distinct clinical presentations and prognoses. Although some are idiopathic (e.g., idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, idiopathic interstitial pneumonias [IIP] and sarcoidosis), the great majority have an underlying etiology, such as connective tissue diseases (CTD), inhalational exposure to organic matter (i.e., hypersensitivity pneumonitis), or certain medications, and genetic disorders (i.e., short telomere syndrome).1,2

The American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society taskforce recognizes the following IIPs: usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), organizing pneumonia (OP), also known as cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (previously referred to as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia), acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP), and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP); note that all these patterns may manifest in patients with CTD. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) and respiratory bronchiolitis-ILD (RB-ILD) are less common and typically found in smokers.3–5 Other less prevalent IIPs are also recognized, but their discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Interstitial lung diseases occur in close to 40% of patients with CTD (also called systemic autoimmune disease) in the course of their disease. Commonly recognized CTDs associated with ILD include rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic sclerosis (SSc), and idiopathic inflammatory myositis (IIM). In other CTDs, like primary Sjogren Syndrome (pSS), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides (AAV), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), ILD have been described and recognized. In the recent years, the increased awareness of CTD-ILD subset of diseases has led to major advances in their understanding and development of therapeutics mainly driven by randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in SSc-ILD. However, in this heterogenous group of conditions, significant gaps exist in screening, early diagnosis, ease of diagnosis, diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, and institution of treatments to change the trajectory of the disease. Yet, ILD being a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, prompt recognition and diagnosis are critical to avoiding delays in treatment. With the exception of the UIP pattern, ILDs associated with CTD in general have better prognoses than their idiopathic counterparts.2

To make an accurate diagnosis, a multidisciplinary, personalized approach is required, with input from various specialties, including pulmonary, rheumatology, radiology, and pathology, to reach a consensus. Nevertheless, in a minority of patients, a definitive diagnosis cannot be established.6,7

Although ILD may be the presenting manifestation of CTD in 15–19% of patients, in the overwhelming majority of cases, ILD occurs during the course of an autoimmune disease.8,9

Differences in the epidemiology and clinical presentation among CTD ILD subsets (see Table 2)Rheumatoid arthritisRA is an autoimmune disease that causes inflammation and damage to the joints, but it can also affect other organs, such as the lungs, eyes, and small arteries. RA-ILD is one of the most common and serious lung complications of RA. Clinically significant lung disease occurs in nearly 10–15% of patients with RA and generally more common in men than women.10,11 Risk factors for RA-ILD include the presence of high titer serologies (rheumatoid factor and anti CCP), active joint disease, high C-reactive protein, male gender, older age, obesity, cigarette smoking, severe extra-articular disease, and exposure to fine particular matter.10–14 ILD is usually suspected when a patient with RA develops dyspnea, cough, auscultatory crackles, or abnormalities on pulmonary function tests (PFTs) or chest radiograph. While ILD is often associated with active or erosive joint disease and frequently postdates the onset of joint symptoms by up to 5 years, it can occasionally proceed joint disease.12 Symptoms present insidiously and include dyspnea on exertion and nonproductive cough. The progression of the disease is quite variable and rarely an acute onset has been described in few cases which has a pathological pattern of acute interstitial pneumonia.

While there is no consensus on when to screen for ILD in patients with RA, the best screening modality is high-resolution CT scan (HRCT) for all ILDs. Patients with RA and risk factors for ILD should certainly be screen for early in the presence of symptoms. The common radiologic and histologic patterns include usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) followed by nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), respiratory bronchiolitis, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, and diffuse alveolar damage.

It is important to determine whether a symptomatic patient with RA is experiencing new respiratory symptoms secondary a new ILD diagnosis, an ILD exacerbation or if there is a superimposed coexistent medical comorbidity or other etiology for lung parenchymal disease (infection in an immunocompromised host, drug-induced lung disease, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, cancer or recurrent aspiration).15

Drug-induced lung disease in RA can be seen with the use of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs such as methotrexate, leflunomide, and rarely sulfasalazine, and also in certain biologic agents like tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (infliximab or adalimumab).16,17

The presence of RA-ILD is associated with a greater mortality compared with the absence of ILD (5-year mortality 36% versus 18% respectively).18 Older age, UIP pattern, significant respiratory impairment at baseline, and frequent acute exacerbations seem to be associated with progression.19–21

The optimal treatment for RA-ILD has not been determined, but some principles must be applied. Given the risk factors, smoking cessation is an important first step. The choice of therapeutic management should involve consideration of extrapulmonary manifestations, especially joint symptoms, and comorbid risk factors like diabetes, response to immunosuppression, risk for infection, and osteoporosis. Case series and clinical experience suggest benefit of using systemic glucocorticoids, selective immunosuppressive agents (like rituximab or abatacept) and recently antifibrotic therapy, such as nintedanib and pirfenidone, which may have a role especially in progressive fibrotic disease.22–25

Systemic sclerosisSSc is a heterogenous chronic inflammatory autoimmune multi-system disease with the highest case fatality among all CTDs. The pathogenesis of SSc is complex and incompletely understood. Immune activation, vascular damage, and concomitant or subsequent fibrosis resulting from excessive synthesis of extracellular matrix with deposition of increased amounts of structurally normal collagen are all known to be important in the development of this condition.26 Interstitial lung disease can affect 50–60% of patients with SSc irrespective of the subtype.27,28 Risk factors for SSc-ILD include rapidly progressive diffuse cutaneous skin involvement, African American ethnicity, higher baseline skin score, serum creatine phosphokinase levels, hypothyroidism, cardiac involvement, and presence of anti-topoisomerase antibodies (anti Scl 70).29,30

Early ILD is often asymptomatic and could sometimes be associated with fatigue. Most patients have cutaneous manifestations of SSc at the time ILD is identified, but occasionally ILD may precede the skin manifestations could be very subtle. It is important to look for other clues like Raynaud's phenomenon, sclerodactyly, nailfold capillary abnormalities, and accordingly screen for baseline serologies like antinuclear antibody and anti Scl 70. Given the high prevalence of ILD in patients with SSc, it is recommended to screen al patients for ILD with baseline chest auscultation, spirometry with diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide, HRCT, and functional capacity assessment.31 The most common radiologic type of ILD in patients with SSc is NSIP followed by UIP. Centrilobular fibrosis is a rare pattern which may be associated with patchy ground-glass consolidative opacities.

The presence of ILD in patients with SSc is an independent predictors of increased mortality (9 years survival rate of approximately 30%).32 The key adverse prognostic factors include low baseline FVC at presentation and increased extent of baseline fibrosis and whole lung disease on HRCT.33 The coexistence of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in SSc-ILD is a poor prognostic risk factor.34 Early screening can change the trajectory of the disease. Also, careful monitoring to assess for progression or response to treatment is equally instrumental.

The treatment of SSc-ILD aims to slow down the progression of lung fibrosis and improve symptoms and quality of life. Through many randomized controlled trials, there has been progress in development of therapeutic to treat SSc-ILD. The main treatment options are immunosuppressive drugs, such as mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide, and biologic therapy such as tocilizumab in the early diffuse cutaneous SSc subset (now approved by FDA for treating SSc-ILD). Among the antifibrotic agents, nintedanib was the first FDA approved drug for the treatment of SSc-ILD in 2019. The optimal comanagement of coexistent gastroesophageal reflux disease is essential. In some cases, lung transplantation may be considered for patients with severe or refractory SSc-ILD.

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathiesIIMs are a family of systemic autoimmune diseases with variable involvement of proximal and truncal musculature, lungs, skin, and joints. Myositis is a term that refers to inflammation of the muscles. There are different types of IIMs, such as polymyositis, dermatomyositis, necrotizing myopathy, and inclusion body myositis. The prevalence of ILD varies widely from 20 to 80% based on reports from different case series.35 In patients with IIM, the factors that predict the development of ILD is important to consider in the decision making to screen and diagnose early. Older age at diagnosis, arthritis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and elevated C-reactive protein are associated with ILD.36

Patients may typically complain of dyspnea and nonproductive cough although some patients are asymptomatic and ILD suspected based on abnormal lung exam or imaging. Besides an inherent parenchymal lung disease, the coexistence of respiratory muscle weakness due to myositis with an added risk of aspiration in patients with dysphagia important considerations in the assessment of patient's symptoms. It is equally important to comprehensively evaluate for any extrapulmonary symptoms/manifestations that involved detailed dermatologic and musculoskeletal assessments.

Early characterization of autoantibodies is a critical diagnostic step. A subset of patients with IIM, can have presence of a clinical syndrome characterized by arthritis, fever, mechanic's hands, Raynaud's phenomenon, myositis, and is frequently associated with ILD. This is defined as antisynthetase syndrome guided by the presence of antisynthetase antibodies, anti Jo 1, anti EJ, anti PL 7, anti PL 12, and anti OJ).37 A unique clinical syndrome is that of a clinical amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM) with a key presenting manifestation of dermatological involvement which has been associated with a rapidly progressive ILD with a higher prevalence in certain ethnic groups (Japan, Korea, China), and associated with the presence of anti MDA 5 antibody.38 In a subset of patients, there is a likelihood of overlap of systemic sclerosis and myositis with the presence of anti PM-Scl antibody.39 Besides these antibody associations, there is a more comprehensive list of myositis associated antibodies with prognostic significance. Common HRCT patterns include NSIP, UIP, a mixed of NSIP and OP, OP and DAD.35,40,41

Poor prognostic factors include male gender, older age at disease onset, clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with anti-MDA 5 antibody, cutaneous involvement (rash), fever, skin ulceration, periungual erythema, elevated creatine kinase, raised ferritin>500ng/mL, UIP pattern on HRCT, and low oxygen saturations at presentation.42

The approach to therapy of IIM-ILD is guided by the severity of respiratory impairment and trajectory of progression along with careful assessment of extrapulmonary manifestations. Glucocorticoids remain the mainstay of initial therapy with steroid sparing immunosuppressive therapy an early consideration. These choices include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and rituximab for more refractory disease.42 For patients with significant myositis, IVIG therapy was recently approved by the FDA. For progressive fibrotic lung disease, nintedanib can be used to stabilize disease. Early institution of both physical therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation therapy is critical to influence the outcome.

Primary Sjogren syndromePimary Sjogren Syndrome is a chronic inflammatory disorder that affects the exocrine glands, especially the salivary and lacrimal glands. It can also cause dryness of the tracheobronchial mucosa, which can lead to a dry cough, recurrent bronchitis, or pneumonitis. Can affect extraglandular organ systems including the skin, lung, heart, kidney, neural, and hematopoietic systems. pSS-ILD is common in women than men and has a median age of onset of 60 years with an estimated prevalence of around 23%.43,44

While there are no clear indications as to when to screen for ILD in an asymptomatic patient, the onset of symptoms like dyspnea, cough with associated decrease in functional capacity should prompt to evaluate for ILD by obtaining a baseline HRCT, PFT, and functional capacity assessment. It is also important to evaluate for extrapulmonary symptoms such as the severity of sicca, Raynaud's phenomenon, musculoskeletal assessments, and any other potential for overlap of CTD. Variable patterns of auto antibody positivity can be expected, often there is presence of anti SSA and/or anti SSB antibodies.

Some studies found an increased risk of developing ILD in patients of older age, male sex, smoking history, a longer disease duration, non-sicca symptoms, elevated CRP and the presence of RF, anti-Ro, and anti-SSA 52kDa antibodies.45–49 The most common radiologic pattern seen is NSIP, followed by lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP), OP, UIP, and DAD.50

Occasionally, ILD is the presenting manifestation of pSS and the presence of sicca symptoms is elicited during the evaluation of ILD. In the event that serological testing is nondiagnostic, a minor salivary gland biopsy may lead to a more precise diagnosis of underlying pSS by the histologic demonstration of lymphocytic sialadenitis. Lung biopsy may need to be considered in patients with a progressive pattern of LIP as a subset might have an underlying pulmonary marginal zone lymphoma (MALT).51 ILD can also increase the risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients with pSS.

The management of pSS-ILD is based on the severity of symptoms, functional impairment, and radiographic findings. There are no controlled studies on the treatment of pSS-ILD, but some patients may benefit from immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, or rituximab, and in progressive fibrotic subtypes, could benefit with nintedanib.

Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody vasculitisPatients with ANCA vasculitis could have multisystemic involvement due to vasculitis often manifested by upper and lower respiratory tract involvement, systemic necrotizing vasculitis and necrotizing glomerulonephritis. The subtype of ANCA vasculitis where ILD has been described the most is in microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), compared with other forms of AAV.52 In small single center studies, ILD has been noted in around 12–15% of patients with MPA.53 The frequent radiographic pattern noted UIP followed by NSIP and also combined pulmonary fibrosis has been described.54 With these reports, it is important to evaluate for ILD in these subsets of patients with ANCA vasculitis and treat accordingly.

Systemic lupus erythematosusIn patients with SLE, ILD is rare manifestation, and a true prevalence estimate is not known. However, some studies have reported a prevalence from 8 to 10%.55,56 ILD risk factors in patients with SLE include being older, male, and having a late onset of SLE.57 In a patient with established diagnosis of SLE, ILD should be considered in the differential diagnosis when presenting with any pulmonary symptoms like dyspnea on exertion (especially of an acute onset), cough, and associated with any decrease in functional capacity.

Imaging with HRCT should be done to better characterize the nature of any lung parenchymal disease. Various patterns have been described in case reports including NSIP, organizing pneumonia, and acute interstitial pneumonias, also diffuse alveolar damage and LIP also have been described.58,59

In patients on immunosuppressive therapy, it is critical to exclude any underlying infectious process before considering change in the approach to the management of lung disease.

Clinical approach to ILD-related autoimmune diseasesClinical evaluation of ILD in a patient with unknown CTDA high index of suspicion is necessary to diagnose CTD in a patient with ILD. Some indicators that suggest patients have associated CTD including younger age at diagnosis, the presence of various extrapulmonary manifestations, including involvement of the joints, muscles, skin, Raynaud's phenomenon, gastrointestinal tract, pleura, pericardium, PAH having a better baseline lung function, and having a family history of rheumatologic diseases (Fig. 1).60,61

It is impossible to differentiate between idiopathic ILD and ILD-CTD solely based on a pulmonary examination; both will exhibit bilateral bibasal crepitus and, if advanced, digital clubbing. When evaluating patients with diffuse interstitial lung diseases, CTD signs (i.e., Raynaud's phenomenon, distal digital fissuring [mechanic hands], digital tip ulceration, hand edema, synovitis, oral ulcers, and rashes), should be sought, preferably in collaboration with a rheumatologist.

To complicate matters, 15–20% of patients with IIP have systemic symptoms and serologic abnormalities suggestive of an autoimmune process, whereas 25% of patients with autoimmune features do not meet the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for a particular CTD. In such cases, the designation of IPAF (interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune characteristics) may be offered.5,62

The involvement of a rheumatologist is instrumental in the diagnosis and management of CTD-ILD. In a prospective study of 60 patients, the addition of a rheumatologist to a multidisciplinary discussion changed the ILD-underlying diagnosis in 40% of cases, preventing eight unnecessary procedures and changing therapy in 56% of patients. Furthermore, rheumatologists can perform office-based nailfold capillaroscopy and salivary gland biopsies, procedures generally unavailable to pulmonary specialists.63,64

Clinical evaluation of ILD in a patient with established CTDWhen pulmonary-ILD involvement is suspected in CTD patients, additional considerations must be considered, particularly that these patients are on immunosuppressants that can affect the lungs, rendering them at risk for opportunistic infections, such as pneumocystis jirovecii, that can mimic ILD. Obtaining a comprehensive clinical history, including the chronology of medication introduction and the onset of symptoms, is essential.

A patient with CTD may not complain of shortness of breath despite having ILD owing to limited mobility. Clinicians should be cognizant of this possibility.65 Part of the workflow in ILD diagnosis includes complete PFTs, HRCT, sometimes bronchioalveolar lavage (BAL), and less frequently, a lung biopsy.

At present, systematic screening for the presence of lung disease in patients with various forms of CTD-ILD with PFTs and HRCT has only been endorsed by professional societies for patients with scleroderma. Despite the high prevalence of ILD in some of the other conditions, as of yet, formal routine screening has not been endorsed for the remaining autoimmune disorders.31,66,67

PFTs are essential for detecting ILD, staging disease severity, and predicting prognosis. They are also crucial for monitoring treatment response, with serial surveillance recommended every 3–6 months. As an initial evaluation, simple spirometry is often insufficient since it may “pseudo-normalize” in patients with emphysema. Spirometry will show a restrictive pattern characterized by low FVC and FEV1 with preserved FEV1/FVC ratio, and plethysmography will reveal reduced TLC that is proportionally diminished compared with FVC unless the patient has an occult obstruction; in such cases, FVC will be 10% lower than TLC. The diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) will also be diminished.68 Clinicians must keep in mind that the association with pulmonary hypertension, which is not uncommon in CTD, may further reduce the DLCO.

For follow-up, FVC and DLCO are the parameters used to evaluate a patient's response to treatment; identifying a progressing patient is essential for changing treatment or for lung transplant referral. The definition of rapid progression is a relative decline in FVC predicted ≥10%; relative decline in FVC predicted ≥5 to <10% with either worsened respiratory symptoms or increased extent of fibrosis on chest HRCT; or a combination of worsened respiratory symptoms and an increased extent of fibrosis on HRCT.69,70

Decline in predicted FVC>10% in 6–12 months has been associated with a substantially increased risk of all-cause mortality, irrespective of the underlying cause of ILD.71,72

In the early stages of ILD, the PFTs might be normal in 15% of patients, highlighting the importance of HRCT in early detection of lung pathology. HRCT protocols for ILD evaluation includes narrow collimation (≤1.5mm) inspiratory supine volumetric and prone images to differentiate ground glass opacities (GGO) from basal atelectasis; the latter will resolve on prone images. Supine expiratory images are also performed to assess for gas trapping.

BAL is not required for assessment of every patient with CTD that we suspect ILD and is primarily reserved for patients in whom infections and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage are suspected. The same reasoning applies to the need for a lung biopsy, which, with the advent of HRCT in this specific subset of patients, is no longer required in most cases.

Distinguishing between CTD-ILD and IIPs from a radiological-pathology correlation standpointSSc, RA, IIMs, pSS, ANCA-vasculitis, and undifferentiated rheumatoid disorders are the most prevalent CTDs that present with IIPs (Table 1).

Relative frequencies of computed tomography imaging patterns among CTD's.

| CTD | UIP | NSIP | OP | LIP | DAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| SSc | + | +++ | + | − | + |

| PM/DM | + | +++ | +++ | − | ++ |

| SLE | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Sjogrens | + | ++ | − | ++ | + |

| MCTD | + | ++ | + | − | − |

Main characteristics of ILD in CTD.a.

| Prevalence of ILD in patients with CTD | ILD pattern | Risk factors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSc-ILD | 50–60%27,28 | NSIP>UIP80,81 | Diffuse cutaneous SSc, higher baseline skin score, African American ethnicity, hypothyroidism, cardiac involvement, Scl-70+29,30 |

| RA-ILD | 10–15%10,11 | UIP>NSIP>OP80,81 | Older age, male sex, obesity, cigarette smoking, exposure to fine particular matter, RF, anti-CCP and RA activity10–14 |

| IMM-ILD | 20–80%35 | NSIP>NSIP/OP, DAD/AIP>UIP35,40,41 | Male gender, older age, arthritis, elevated sed rate and CRP, presence of Antisynthetase antibodies, anti-MDA-5 antibodies, CADM35–40 |

| pSS-ILD | 23%43,44 | NSIP>LIP>OP>UIP>DAD50 | Older age, male sex, smoking, disease duration, non-sicca onset of disease, ANA, increased CRP, Anti SSA 52kDa antibodies45–49 |

| SLE-ILD | 8–10%55,56 | NSIP>UIP, OP, DAD,LIP58,59 | Older age, male sex, late onset of SLE57 |

| AAV-ILD | 12–15%53 | UIP>NSIP54 | MPA, MPO-ANCA52 |

AAV-ILD, ANCA-associated vasculitis-interstitial lung disease; anti-CCP, anti-citrullinated protein antibodies; AIP, acute interstitial pneumonia; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; CADM, clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis; OP, organizing pneumonia; CRP, C-reactive protein; CTD, connective tissue diseases, DAD, diffuse alveolar damage; IIM-ILD, idiopathic inflammatory myopathies-interstitial lung disease; ILD, interstitial lung disease; LIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; MPO-ANCA, myeloperoxidaseantineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; sLE, Systemic lupus erythematosus; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Any IIP pattern can manifest in patients with CTD, and both treatment and prognosis differ between CTD-ILD and other fibrotic diseases, especially, IPF; therefore, it is crucial to make a precise diagnosis, and HRCT is a fundamental component of this process. Findings suggesting an underlying CTD when an IIP pattern is encountered are the multicompartment involvement, including pleural effusions, pericardial thickening, pericardial effusion, esophageal abnormalities, and airway involvement.7,73,74

The usefulness of a surgical biopsy in diagnosing ILD in established CTD remains debatable. The need for a lung biopsy to establish an accurate diagnosis has been limited to specific circumstances, such as when medication-induced pulmonary toxicity must be excluded, or on occasion to evaluate for occult infection or malignancy.75 As we will discuss later, there are certain lung biopsy characteristics that can indicate the presence of CTD and help distinguish CTD-associated diffuse lung disease from idiopathic variants.

Usual interstitial pneumonia UIP patternA UIP pattern, commonly associated with IPF, is defined as basilar and peripheral predominant reticulation, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing (clustered cysts with well-defined relatively thick walls involving the subpleural lung), and/or and the absence of inconsistent features (ground-glass opacity unassociated with other features of fibrosis, nodules, cyst, gas trapping, etc.).76 When significant GGO is present in the context of a UIP pattern at imaging, the clinician is obligated to exclude chronic aspiration events and gastroesophageal reflux and look for other radiologic signs indicative of collagenopathy, particularly in younger female patients.

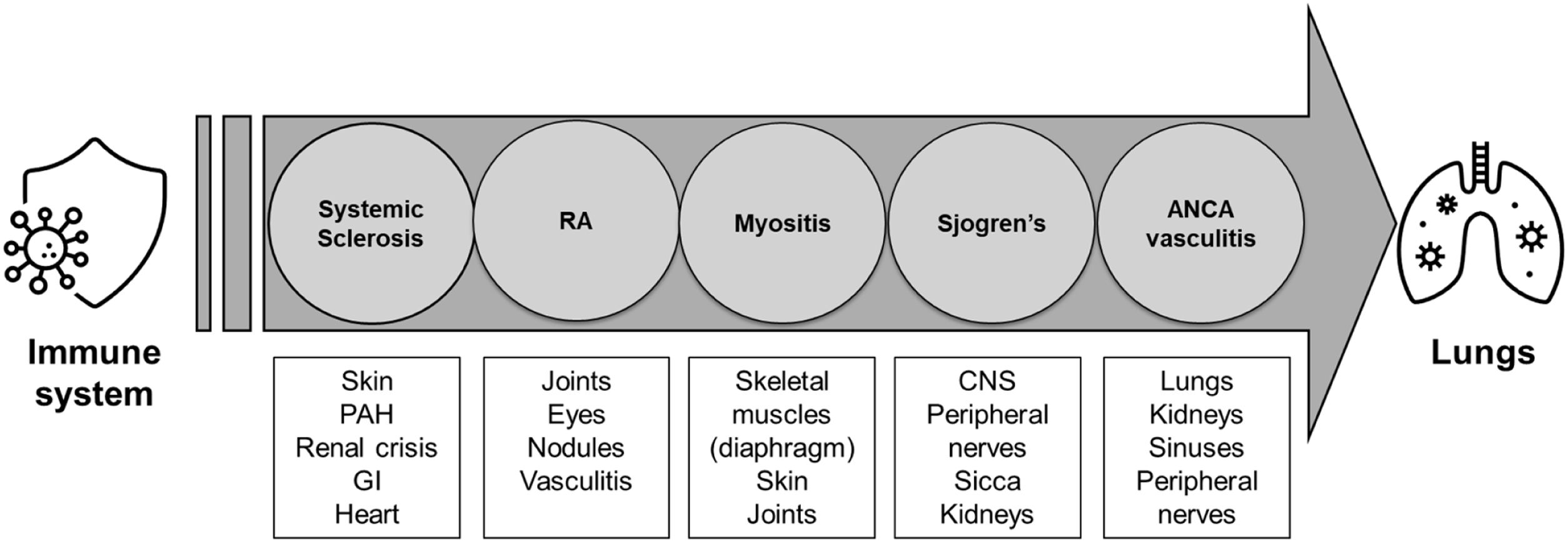

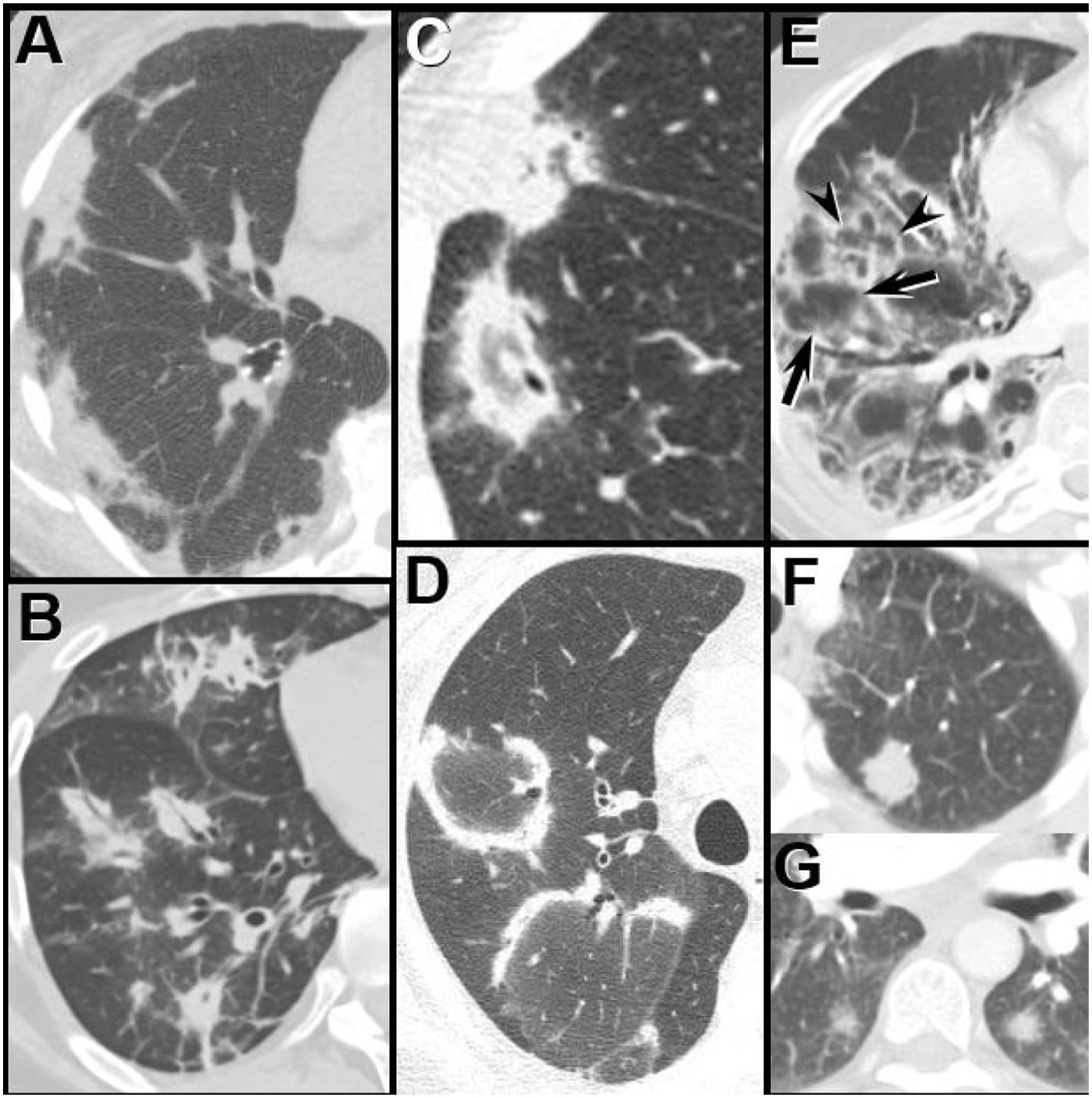

Three CT imaging findings described by Chung et al., 25 suggest the diagnosis of CTD-associated UIP over IPF-associated UIP: the exuberant honeycombing sign, the anterior upper lobe sign, and the straight -edge sign (Fig. 2). While the sensitivity of each sign was low, the specificity for each approximates 87%. The authors suggest that when all 3 signs are present a thorough workup for CTD-ILD should be pursued, including referral to the rheumatology department.77

The UIP pattern: HRCT features favoring a connective tissue-associated etiology from IPF.25 (A) The “exuberant honeycombing” sign-cyst formation constituting greater than 70% of the fibrotic portions of the lung. Prone HRCT image in a patient with RA shows a UIP pattern with extensive basal honeycombing; compare with the definite UIP pattern at HRCT in an IPF patient (B). (C) The “anterior upper lobe sign”. Axial HRCT image through the upper lungs in a patient with RA shows concentrated fibrotic change with honeycombing; compare with the typical appearance of fibrotic change in the upper lobes in a patient with IPF (D). (E) The “straight-edge” sign. Coronal CT image in a patient with RA shows comparatively isolated extensive honeycombing and fibrotic change in the bases, showing a sharp demarcation in the craniocaudal plane (between arrowheads), and lack of substantial extension along the lateral pulmonary parenchyma cranially. Compare with coronal CT in a patient with IPF (F), which shows peripheral and basal predominant fibrotic lung disease, but with relatively greater lateral mid and upper lobe involvement (arrows).

By far, the most common CTD associated with UIP pattern is RA, present in 56–61% of patients.78,79 The UIP pattern is not limited to RA-almost any CTD, including systemic sclerosis, mixed CTD, myositis, and Sjogren, can exhibit a UIP pattern in a minority of cases. Furthermore, RA can also exhibit other ILD patterns, including NSIP (33%) and OP (11%), as well as serositis, nodules, and obstructive airway disease.

The UIP pattern is defined histopathologically by a combination of patchy interstitial fibrosis with alternating areas of normal lung; temporal and spatial heterogeneity of fibrosis characterized by scattered fibroblastic foci in the background of dense acellular collagen; and architectural destruction due to chronic scarring or honeycomb change.3,76,4 UIP It is not unique to IPF, as it is also present in other ILDs, including hypersensitivity pneumonitis, asbestosis, drug toxicity, and autoimmune diseases. If honeycombing is absent, one should be alert to the possibility of additional diagnosis such as NSIP.

Cipriani, et al., discovered significant histological differences between CTD-UIP and idiopathic-UIP, including fewer and smaller fibroblastic foci and larger lymphoid aggregates. Moreover, they discovered that coexistence with other IIP histologic patterns, such as NSIP, found distant from the edge of dense fibrosis was the most distinguishing characteristic.80

The UIP pattern in the majority of the CTDs is associated with a less favorable prognosis; however, when associated with RA, the prognosis is even worse, with the same survival rate as UIP-IPF.75

Non-specific pneumonia patternNSIP is the most common pattern found in CTD.4,81 The NSIP pattern can occur in any CTD but is most common in SSc82,83 and IMM, the latter in combination with OP.

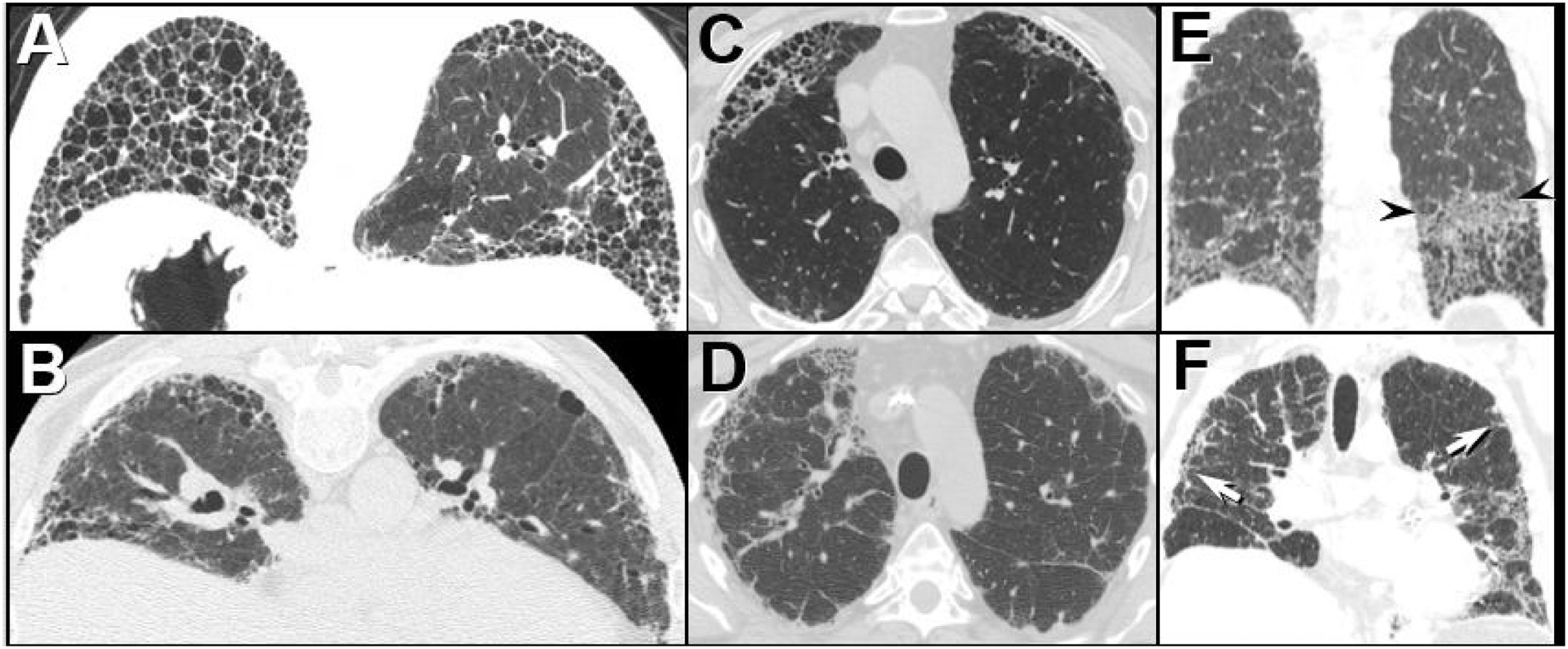

HRCT findings of NSIP differ from UIP in that the NSIP tends to be more uniform, but shares with the UIP pattern the preference to affect the lower lobes with subpleural predominance. Subpleural sparing, when present, distinguishes the NSIP pattern from UIP. Honeycombing is rare, said to be present in up to 27% of patients in one study, although is typically encountered far less commonly. In the early phases, GGO predominates (cellular” NSIP); as the disease progresses, delicate reticulation appears underneath the GGO, and as the disease advances, reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and architectural distortion become more prevalent (“fibrotic” NSIP).84 Regardless of phase, the CT appearance of NSIP is usually temporally and spatial homogeneous. These imaging features are present in both idiopathic and CTD-associated NSIP (Fig. 3).

NSIP: idiopathic versus connective tissue-associated pulmonary disease. (A and B) Axial HRCT through the mid and lower lungs in a patient with idiopathic NSIP shows basal predominant ground-glass opacity, fine reticulation, and traction bronchiectasis. Note presence of subpleural sparing (arrowheads). (C and D) Axial HRCT through the mid and lower lungs in a patient with scleroderma shows findings similar to the patient with idiopathic NSIP, including basal predominant ground-glass opacity, reticulation, and traction bronchiectasis. A clue to the presence of scleroderma is the dilated esophagus (arrow).

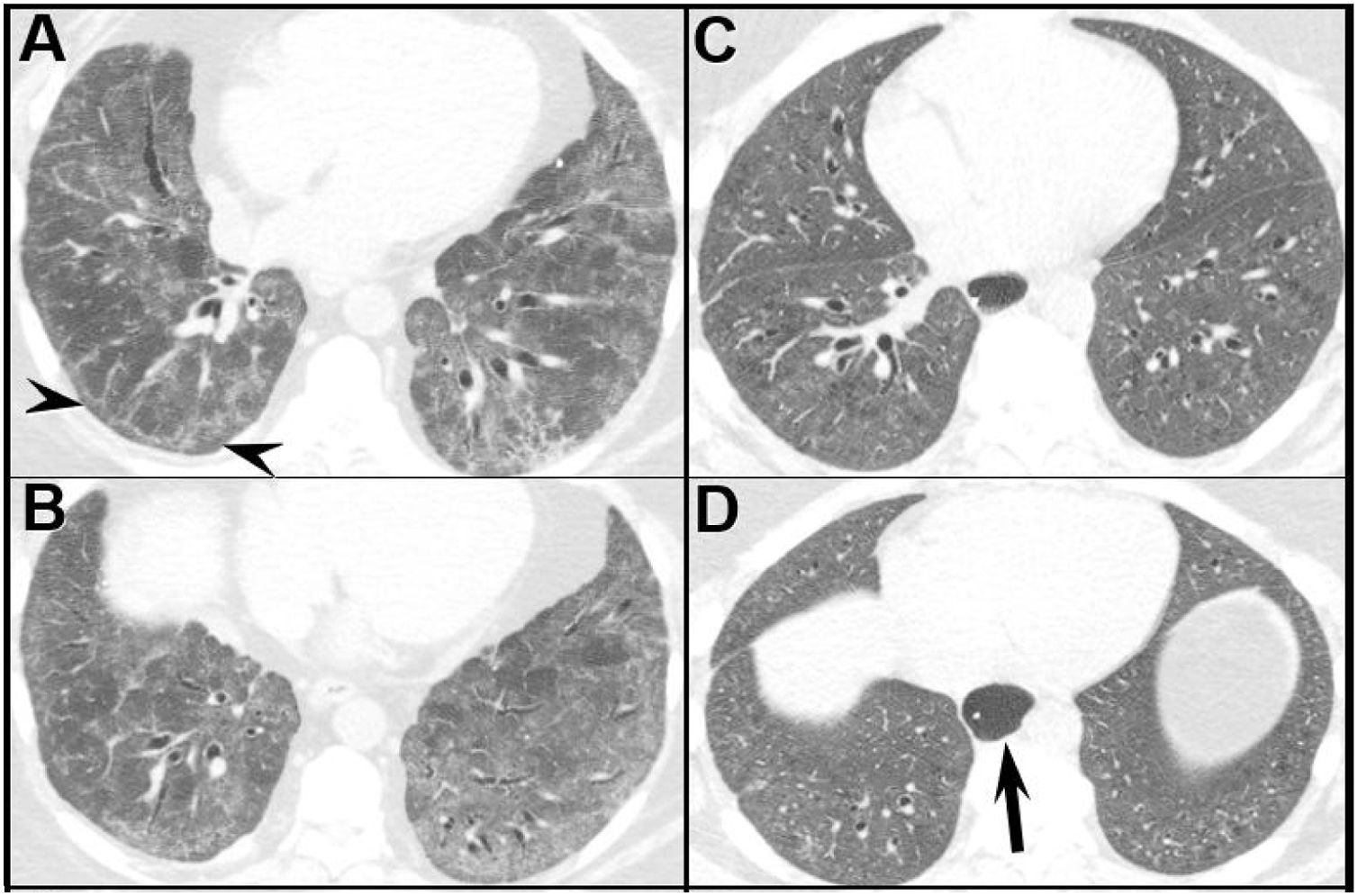

An OP pattern manifests as patchy, peripheral, often frankly subpleural, and/or peribronchiolar GGO and/or consolidation; opacities may show migratory behavior over time. Perilobular opacities, which may resemble interlobular septal thickening, and the reversed ground-glass halo sign (consolidation surrounding GGO) may occur. Rarely nodules may be a manifestation of OP (Fig. 4). As with NSIP, the imaging manifestations of CTD-associated OP are indistinguishable from cryptogenic OP.

Organizing pneumonia patterns at HRCT in patients with dermatomyositis. (A) Subpleural consolidation; (B) Peribronchial consolidation; (C and D) The reverse ground-glass halo, or atoll, sign – a complete (C) or incomplete (D) ring of consolidation surrounding ground-glass opacity; (E) Perilobular opacity. Note the linear increased attenuation, simulating interlobular septal thickening outlines individual (arrowheads) and contiguous secondary pulmonary lobules (arrows), creating a polygonal appearance. (F and G) Nodules, both solid (F) and subsolid (G).

When a basal predominant fibrotic abnormality presents with findings that also suggest an OP pattern, CTD, particularly idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIMs) or antisynthetase syndrome (AS), should be considered. AS may occasionally present with acute respiratory failure manifesting on imaging as diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) superimposed on a basal predominant IIP pattern.

Diffuse alveolar damage patternDAD presents as multifocal, bilateral areas of GGO and/or consolidation, typically without a clear zonal predilection; a background of mild interlobular septal thickening may be seen. The imaging appearance is relatively non-specific and can be mimicked by other processes that may occur in CTD patients, including diffuse alveolar hemorrhage or infection.

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia patternThe presence of an LIP pattern on HRCT prompts an assessment of Sjogren syndrome. The LIP pattern is often nonspecific at HRCT, presenting as areas of GGO that may be centrilobular associated with interlobular septal thickening, but one manifestation – multiple, thin-walled cysts that may show a basal predominance – may be encountered.

Histologically, the nodules exhibit lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrates, whereas the GGO demonstrates diffuse interstitial infiltration. In some LIP cases nodules has been linked to amyloid deposits and we are obligated for look and rule out MLAT-Lymphoma.85,86 LIP is considered an immune dysregulation, 5% of cases can progress to lymphoma; therefore, frequent monitoring is essential.

Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF)Some patients with ILD were considered idiopathic due to a lack of a clear etiology; however, if associated findings suggestive of an autoimmune etiology were present, these cases were designed with terms such as lung-dominant connective tissue disease (CTD) and autoimmune-featured ILD.60,87

To facilitate future studies by standardized diagnostic criteria, an International Working Group on Undifferentiated Forms of CTD-ILD was formed to develop consensus regarding nomenclature and criteria for classification for cases of ILD with this “autoimmune flavor”, the term IPAF was created.5

Classification criteria for IPAFIf the patient has HRCT or lung biopsy evidence of ILD but does not meet CTD criteria, three central domains should be recognized: a clinical domain consistent with specific extra-thoracic manifestations, a serologic domain based on the presence of specific circulating autoantibodies, and a morphologic domain consistent with specific chest CT and/or histopathologic findings. To qualify as an IPAF case, the patient must meet the aforementioned requirements and exhibit at least one characteristic from at least two domains.5

Regarding these criteria, there are numerous limitations and debatable areas that are beyond the scope of this chapter. However, despite its limitations, it has the advantage of classifying some ILD cases that were previously thought to be idiopathic, leading to a more effective treatment strategy. Additionally, this adopted nomenclature permits future research studies.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH)PH refers to a pathophysiologic disorder characterized by an elevated mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) at rest. It can be idiopathic or associated with different diseases, including CTD. It is defined by a mPAP of 20mmHg or more measured by right heart catheterization.88

The clinical classification has as its goal to categorize conditions associated with PH based on pathophysiologic mechanisms, clinical presentation, and hemodynamic characteristics. Five groups have been recognized. PAH-CTD is classified as a Group 1, Associated PAH (Table 3).

World Health Organization (WHO) classification for pulmonary hypertension.

| WHO classification | Disease states |

|---|---|

| Group 1: Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) | 1.1 Idiopathic PAH (IPAH)1.2 Heritable PAH (HPAH)1.3 Drug and toxin-induced PAH (DPAH)1.4 PAH associated with:1.4.1 Connective-tissue disease1.4.2 HIV infection1.4.3 Portal Hypertension1.4.4 Congenital heart disease1.4.5 Schistosomiasis1.5 PAH long-term responders to calcium- channel blockers1.6 PAH with overt features of venous or capillary involvement (PVOD or PCH)1.7 Persistent PH of the newborn |

| Group 2: Pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease | 2.1 PH due to heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction2.2 PH due to heart failure with reduced LVEF2.3 Valvular heart disease2.4 Congenital or acquired cardiovascular conditions leading to postcapillary PH |

| Group 3: Pulmonary hypertension associated with lung disease | 3.1 Obstructive lung disease3.2 Restrictive lung disease3.3 Other lung disease with mixed restrictive-obstructive pattern3.4 Hypoxia without lung disease3.5 Developmental lung disorders |

| Group 4: Pulmonary hypertension associated with pulmonary artery obstructions | 4.1 Chronic thromboembolic PH4.2 Other pulmonary-artery obstructions |

| Group 5: Pulmonary hypertension with unclear and/or multifactorial mechanisms | 5.1 Hematologic disorders5.2 Systemic and metabolic disorders5.3 Others (e.g., chronic renal failure with or without hemodialysis and fibrosis mediastinitis)5.4 Complex congenital heart disease |

PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; PH: pulmonary hypertension; IPAH: idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; HPAH: heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension: DPAH: drug and toxin-inducted pulmonary arterial hypertension; PVOD: pulmonary veno-occlusive disease; PCH: pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction.

After idiopathic PAH (IPAH), PAH-CTD is the second most prevalent form of PAH, and SSc especially in its limited variant, is the most common cause of PAH-CTD, followed by SLE, mixed CTD, and, infrequently, DM and Sjogren Syndrome. In the case of SLE, clinicians must rule out chronic thromboembolic PAH (CTEPH), which could be present mostly in the setting of antiphospholipid syndrome.

CTD could be affected by all groups of PH. For instance, SSc, could be associated with pre-capillary PAH due to narrowing of the artery vasculature. Moreover, left heart disease, such as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction due to systemic HTN, is not uncommon in this population, resulting in group 2 PH, and group 3 PH may also be present due to ILD and its secondary chronic hypoxemia.65

In SSc, the prevalence of PAH is 5–19%, with an annual incidence of developing PAH of 0.7–1.5%. Based on this evidence, annual screening for PAH is recommended. In contrast, the prevalence of PH in SLE is less than 4%; current guidelines recommend annual screening only if patients have symptoms of right ventricle dysfunction such as dyspnea and, in more advanced cases, edema, chest pain, or syncope.89

Screening tools include blood biomarkers such as the brain natriuretic peptide, PFTs, electrocardiogram, cardiopulmonary stress test, and transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). TTE has a sensitivity and specificity of 85% and 74%, respectively; however, RHC remains the gold standard for the final diagnosis and classification of PH. When PAH is diagnosed, vasoreactivity testing should be done in cases of idiopathic, heritable, or drug-associated PAH (DPAH), but it is not recommended for patients with CTD.89

Once diagnosis is proven, risk stratification must be determined based on functional status, imaging, hemodynamics, exercise capacity, and biomarkers (Tables 4 and 5).

World Health Organization (WHO) functional assessment for pulmonary hypertension.

| WHO classification | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Class I | No limitation in physical activity. |

| Class II | Slight limitation of physical activity. |

| Class III | Marked limitation of physical activity. |

| Class IV | In ability to perform any physical activity without symptoms. |

Comprehensive risk assessment in pulmonary arterial hypertension (three-strata model).

| Determinants of prognosis | Low risk | Intermediate risk | High-risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO-functional class | I | II, III | IV |

| 6MWD | >440m | 165–440m | <165mters |

| Biomarkers: BNP or NT-proBNP | BNP<50ng/L, NT-proBNP<300ng/L | BNP 50–800ng/LNT-proBNP 300–1100ng/L | BNP>800NT-proBNP>1100ng/L |

| Echocardiography | RA area<18cm2TAPSE/sPAP>0.32mm/mmHgNo pericardial effusion | RA area 18–26cm2TAPSE/sPAP 0.19–0.32mm/mmHgMinimal pericardial effusion | RA area>26cm2TAPSE/sPAP<0.19mm/mmHgModerate or large pericardial effusion |

| Hemodynamics | RAP<8mmHgCI≥2.5L/min/m2 | RAP 8–14mmHgCI 2.0–2.4L/min/m2 | RAP>14mmHgCI<2.0L/min/m2 |

WHO: world health organization; 6MWT: 6minute walking test; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; NT-proBNP: N-termnial pro b-type natriuretic peptide; RA: right atrium; TAPSE: tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; sPAP: systolic pulmonary arterial pressure; CI: cardiac index.

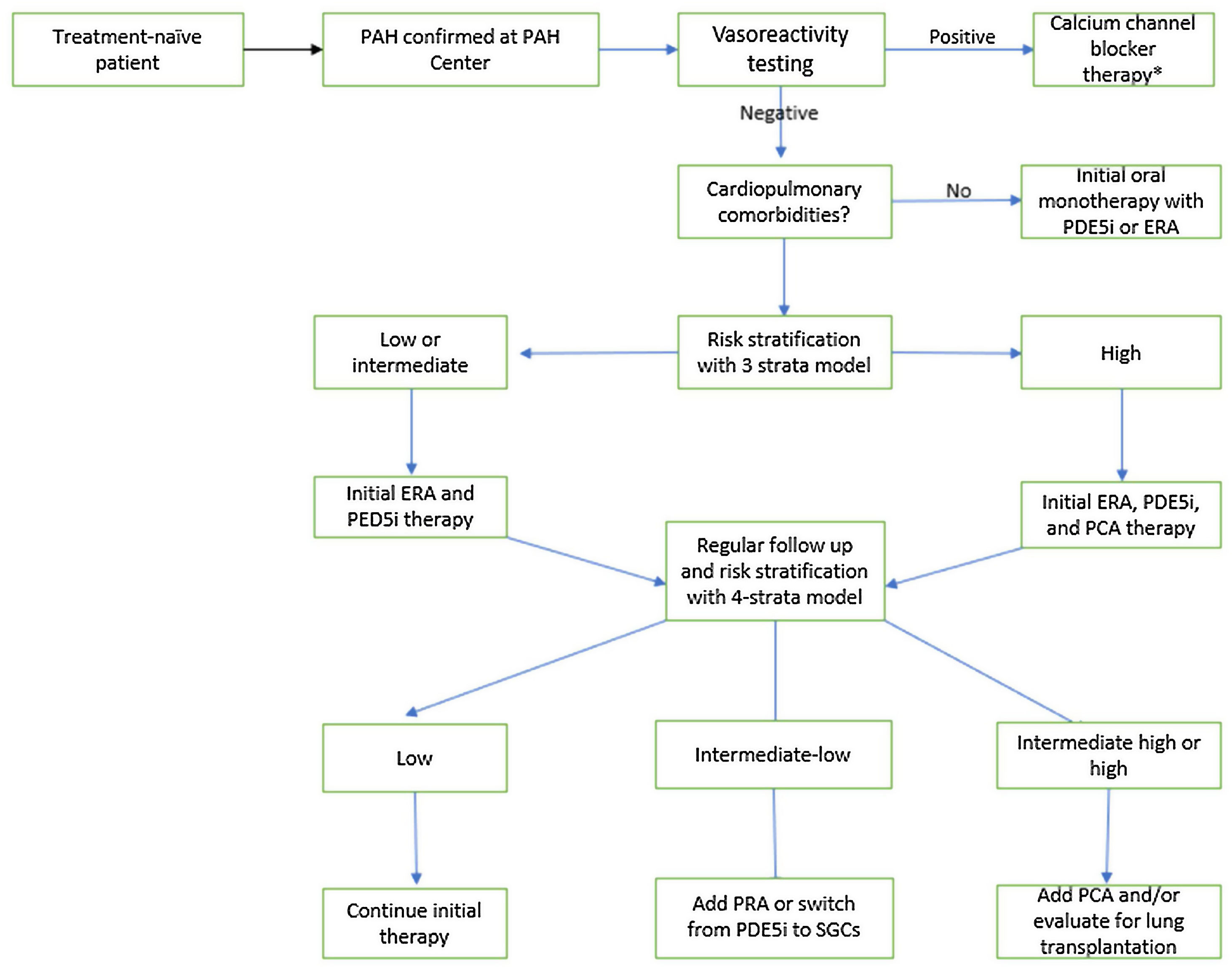

Fig. 5 summarizes a treatment algorithm, highlighting some different approaches in patients with and without associated cardiopulmonary comorbidities. For those without it and with low or intermediate risk, initial combination therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE5-i) is recommended. In patients presenting at high risk, initial therapy with intravenous or subcutaneous prostacyclin analogs should be considered, combining it with oral agents. For patients with associated cardiopulmonary abnormalities, initial monotherapy is advised, with PDE-5 being the most widely used. Additional therapy adjustments should be made on an individual basis.

Treatment algorithm for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Adapted from 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. *As explained in the text applies only for patients with IPAH, HPAH and DPAH. Adapted from Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, Badagliacca R, Berger RMF, Brida M et al., 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2022;43:3618–731. PAH: Pulmonary Artery Hypertension; PED5i: Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor; ERA: Endothelin Receptor Antagonist; PCA: Prostacyclin Analogs; PRA: Prostacyclin Receptor Agonist; SGCs: Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulators.

A recent trial evaluated the effect of inhaled Treprostinil in patients with PH secondary to ILD, demonstrating improvement in exercise capacity from baseline, assessed through a 6-minute walk test, as compared with placebo.90

Role of immunosuppressive therapy in CTD-ILDThe use of immunosuppressive therapy in CTD ILD is mainly driven by randomized controlled trials in patients with SSc ILD and subset analysis in patients with progressive fibrotic ILD. While oral cyclophosphamide has been shown to have a short-term stabilization of ILD based on serial FVC assessments up to 1 year, oral mycophenolate mofetil at a goal dose of 2–3g per day has been shown to be better tolerated than cyclophosphamide and leading to stabilization of ILD in patients with SSc-ILD.91,92 Tocilizumab, a humanized anti interleukin 6 receptor antibody of the IgG 1 subclass, has been shown to slow the rate of decline in pulmonary function in a subset of patients with early diffuse cutaneous SSc-ILD, and has been approved for use by the FDA to treat SSc-ILD.93 Recently, rituximab infusion therapy was found to be not superior to cyclophosphamide to treat patients with CTD ILD with both groups have increase in FVC at 24 weeks in addition to clinical improvements in patient reported quality of life.94 Further, rituximab was associated with fewer side effects. The therapeutic data in treatment of RA-ILD has mainly been from smaller single center studies showing benefits with immunosuppressive therapy like rituximab and abatacept in stabilizing interstitial lung disease.

Role of antifibrotics in CTD-ILDBesides immunosuppressive therapy, anti-fibrotic therapy with nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, authorized initially for the treatment of IPF, has been approved as an additional therapy for the treatment of progressive fibrotic non-IPF ILD (PPF-ILD), based on two randomized, controlled trials: the SENSCIS (Nintedanib for Systemic Sclerosis-related Interstitial Lung Disease) and the INBUILD (Nintedanib in Progressing Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Disease) trials.95,96

PPF-ILD has been defined as the presence of at least two of the three following criteria within the previous year: deterioration of respiratory symptoms, decline in FVC>5% or DLCO (corrected for Hb)>1, or radiologic evidence of disease progression.97

SENSCIS evaluated the effect of nintedanib on 576 patients (nearly half of whom were taking MMF at the time of enrollment), who were distributed in placebo and treatment groups, demonstrating a significantly reduced annual rate of decline in FVC in the treatment group.95

The INBUILD trial evaluated nintedanib in 663 with progressive ILD, of these, 170 had various forms of CTD-ILD, and of those, about 50% had RA-ILD. The study revealed a significant reduction in the rate of FVC decline over 52 weeks in the nintedanib group.96

In conclusion, based on the current evidence, immunosuppressive therapy must be started in patients with ILD associated with CTD, and anti-fibrotic therapy should be added in case of progressive fibrosis. The question about the indication for anti-fibrotic therapy as an initial therapy in patients with evidence of fibrosis at the time of the initial evaluation has not been resolved yet.

Role of lung transplantation in CTD-ILDLung transplantation should be considered for patients with advanced, refractory ILD associated with CTD, applying the same criteria as in other forms of chronic lung diseases, following multiple studies that have demonstrated no difference in survival or allograft dysfunction among patients with CTD-ILD when transplantation is indicated.98 Recurrent non-pulmonary rheumatologic manifestations after lung transplant are rare, and even esophageal dysfunction and its aspiration risks (especially in patients with SSc) are not considered a contraindication, but a comprehensive assessment of swallowing and esophageal dysfunction must be completed before listing.98,99

ConclusionsThe knowledge of interstitial lung disease has evolved over the last few decades, and autoimmune disorders are recognized as an important underlying etiology, with the possibility of offering a specific treatment with not only immunosuppressive agents but also antifibrotics. ILD conveys high morbidity and mortality. Rapid recognition and a multidisciplinary approach, with input from a pulmonologist, rheumatologist, radiologist, and pathologist, are necessary to obtain the best tailored management strategy.

FinancingNone.

Conflict of interestsNone.

None.