Two of the three most prevalent bacterial genera associated with human diseases caused by meat consumption are Campylobacter (mainly in poultry meat) and Yersinia (in pork meat). As its detection and quantification is not regulated by the European legislation (except for the quantification of Campylobacter in poultry channels), several samples of chicken burgers from different establishments including supermarkets and retail trade outlets in Reus (Spain) were processed to ensure microbiological safety. Microbiological criteria and procedures have been those included in the European standards for Campylobacter (Regulation No. 2017/1495) and Yersinia (ISO 10273:2917). Results showed the absence of Campylobacter spp. in all samples, but high counts (104 to 5×105CFU/g) of typical colonies (“red bull's eye” morphology) on CIN medium compatible with Yersinia spp. The biochemical profile of the strains from the typical colonies, and their subsequent molecular identification using MALDI-TOF MS enabled us to identify Yersinia intermedia in just one sample, and Pseudomonas and Serratia liquefaciens in the remaining ones. These findings call into question the usefulness of CIN medium for detecting Yersinia spp. in food. Moreover, the presence of high counts of psychrotolerant bacteria from the genera Pseudomonas and Serratia highlight the need to improve hygienic conditions in the procedures used to produce meat derivatives.

Dos de los tres géneros bacterianos más prevalentes en enfermedades humanas asociadas al consumo de productos cárnicos son Campylobacter (mayoritariamente en carne de ave) y Yersinia (en carne de cerdo). Dado que su detección y cuantificación no está regulada por la legislación europea (excepto la cuantificación de Campylobacter en canales de aves), para estudiar la ausencia de riesgo microbiológico se decidió procesar varias muestras de hamburguesas de pollo procedentes de diferentes establecimientos entre los que se encontraban supermercados y puntos de venta de comercio minorista de la ciudad de Reus (España). Los criterios y procedimientos microbiológicos han sido los contemplados en las normas europeas para Campylobacter (Reglamento 2017/1495) y la norma ISO 10273:2917 para Yersinia. Los resultados mostraron la ausencia de Campylobacter spp. en todas las muestras, pero recuentos elevados (104 a 5×105 UFC/g) de colonias típicas (morfología “ojo de buey rojo”) en medio CIN compatibles con Yersinia spp. El perfil bioquímico de las cepas de las colonias típicas en CIN y su posterior identificación molecular mediante MALDI-TOF MS nos permitió identificar a Yersinia intermedia en una sola muestra, mientras que el resto de las colonias fueron identificadas como Pseudomonas spp. y Serratia liquefaciens. Debido a estos hallazgos, la utilidad del medio CIN para la detección de Yersinia spp. en alimentos queda en entredicho. Además, debe considerarse la necesidad de mejorar las condiciones higiénicas en los procedimientos utilizados para producir derivados cárnicos, debido al elevado recuento de bacterias psicrotolerantes pertenecientes a los géneros Pseudomonas y Serratia.

Foodborne diseases (FBDs) are an important and growing public health concern worldwide15. According to the World Health Organization, these diseases may be caused by the consumption of food contaminated with microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses or parasites or chemical substances like heavy metals27. The three types of foodborne illness are: intoxication (the toxin produced by the pathogens causes food poisoning), infection (caused by the ingestion of food containing pathogens), and toxic-infections (pathogens producing toxins while growing in the human intestines)3,10,23. Moreover, the Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group (FERG) of the World Health Organization estimated that 31 FBDs caused over 600 million cases of illnesses and 420000 deaths worldwide in 2010. Furthermore, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates there are about 48 million cases of foodborne illness each year in the U.S. population19. The contamination of food can be produced at any stage of the manufacturing, delivery and consumption chains, and consequently the consumption of contaminated food or water can result in a FBD in the host1,12,16,17. In addition, food animals are the major reservoirs of many food-borne zoonotic bacterial pathogens, and food products of animal origin are the main vehicles of transmission1,11,14. Bacteria can reach the gastrointestinal tract and proliferate, leading to the secretion of toxins and structural virulent factors that are responsible for their pathogenesis. This can produce a wide range of illnesses in the host, the most frequent being enteritis with or without moderate fever10,15,27. The principal bacterial pathogens that are responsible for most FBDs are species belonging to the genera Campylobacter, Listeria, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia and Escherichia coli1,11,18.23. Due to the high incidence of these microorganisms, public health surveillance includes their detection (and eventual quantification), establishing adequate control mechanisms over the foods involved as vehicles of poisoning, and elucidating the origin of epidemic outbreaks once they have occurred11,27. The main foods implicated in outbreaks of food poisoning are milk, eggs, fish, meat (usually from poultry and pork), and all their derivatives1,16. Specifically, poultry meat (mainly chicken) ranks first in terms of production on a global scale, and is the main route of transmission of some microorganisms causing poisoning in Europe, such as Campylobacter spp., and Enterobacteriales (i.e. Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, and E. coli)1,2. With respect to the control of Campylobacter spp., the Commission Regulation (EU) No. 2017/1495 establishes the microbiological criteria and hygienic procedures that must be fulfilled regarding Campylobacter in broiler carcasses. There is no official legislation for Yersinia spp. establishing maximum acceptable limits in food; however, ISO 10273:2917 is available to establish procedures for the detection of Yersinia enterocolitica in the food chain20. Nonetheless, the incidence of these infections is vastly underestimated, and since food poisoning is a major public health concern, a specific legislation to regulate maximum acceptable limits for Campylobacter spp. and Yersinia spp. in food is needed.

The main objective of our study was to detect and quantify both bacterial genera in chicken meat burgers, and assess whether this food represents a potential risk to the health of consumers.

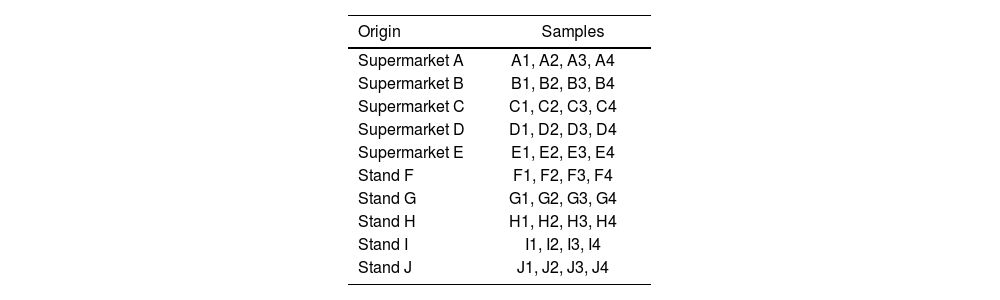

Material and methodsSample collectionReus, the capital city of the Baix Camp region, in the south of Tarragona province (Catalonia, Spain), was chosen as the site for sample collection, because its companies process around 200000 chickens for meat/year (Nombre d’explotacions i capacitat per municipi. 2023) but also because the CESAC (Poultry Health Center of Catalonia and Aragon Communities) is located there. A total of 40 chicken burger samples were acquired, 20 from five national and international chains of supermarkets and the same number of samples from five commercial stands in the Central Market of Reus city (Tarragona province, Spain) (Table 1).

Sources of chicken meat burger samples acquired in the city of Reus (Tarragona province, Spain). The term ‘supermarkets’ refers to large retail chains operating both in Catalonia and throughout Spain. The category ‘stands’ includes various individual stalls located in the Central Market of Reus.

| Origin | Samples |

|---|---|

| Supermarket A | A1, A2, A3, A4 |

| Supermarket B | B1, B2, B3, B4 |

| Supermarket C | C1, C2, C3, C4 |

| Supermarket D | D1, D2, D3, D4 |

| Supermarket E | E1, E2, E3, E4 |

| Stand F | F1, F2, F3, F4 |

| Stand G | G1, G2, G3, G4 |

| Stand H | H1, H2, H3, H4 |

| Stand I | I1, I2, I3, I4 |

| Stand J | J1, J2, J3, J4 |

All burger samples were transported to the laboratory in a thermal bag at 4−7°C and stored for 3h in a refrigerator at 5±1°C before processing.

Sample processingSamples were homogenized in a stomacher (Stomacher® 400 Circulator (Seward Ltd., West Sussex, UK)) in accordance with the UNE-EN ISO 10273:2017 standard and UE legislation No. 2017/1495. A mixture of 225ml of sterile peptone water 0.1% (w/v) and 25g of each sample was homogenized for 30min at 230rpm. Then, 1ml of a homogenized mixture from each sample was aliquoted to tubes containing 9ml of Ringer solution to prepare 1:10 and 1:100 dilutions.

Presumptive detection and quantification of Campylobacter spp. and Yersinia spp.For presumptive detection and quantification of colony-forming-units (CFU) per gram of sample of Campylobacter spp. and Yersinia spp., 1ml from direct samples and each dilution (1:10 and 1:100) was inoculated onto BD Campylobacter Agar (Butzler) for Campylobacter spp., using a Drigalski spatula, and the Petri dishes were incubated at 42°C from 48h to 7 days under microaerobic conditions (oxygen, 6–16%; carbon dioxide, 2–10%; and nitrogen, 80% using Gas Pak EZ Campy container sachets (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA)). Petri dishes were checked every day for 7 days and colonies considered presumptive for Campylobacter spp. were those greyish/colorless, mucoid, with irregular borders and a tendency to spread through the inoculation streak. For detection and quantification of Yersinia spp. Yersinia Selective agar plates (CIN; Laboratories Conda S.A., Spain) with Yersinia Selective Supplement (CIN), in accordance with ISO 10273:2017, were inoculated. Petri dishes were incubated at 30°C for 48h, and the colonies with a red bull's eye appearance were considered presumptive for Yersinia spp.

Yersinia spp. phenotypic presumptive identificationFor red bull's eye bacterial colonies from each burger sample, Gram staining, oxidase and urease tests, and growth on Kliger Iron Agar (KIA), Lysine Iron Agar (LIA), Sulfide Indole Motility (SIM), Motility Indole Ornithine (MIO), and Simmons Citrate Agar were performed5. In the absence of typical colonies in a processed burger sample, an atypical colony was phenotypically characterized.

MALDI-TOF MS identificationOnly a set of strains representing the bacterial phenotypic diversity in the burger samples was selected for identification using this methodology. Identification was carried out using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) coupled mass spectroscopy (MS), using MALDI Biotyper MSP Identification Standard Method 1.1 (Bruker®) version 9 of the Biotyper database. MALDI-TOF MS identifications were classified using modified score values proposed by the manufacturer: a score value ≥2 indicated species identification; a score value between 1.7 and 1.9 indicated genus identification, and a score value <1.7 indicated no identification.

Statistical analysisTo compare the means of two independent groups (red bull's eye CFU/g vs. atypical CFU/g), a two-sample t-test was used if the data were normally distributed; otherwise, the Mann–Whitney U test was performed for non-normal distributions. Shapiro–Wilk test was used to evaluate if the variables were or were not normally distributed. Based on this result, either the t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test were performed. Statistical analyses were conducted using Julius (https://julius.ai/chat).

ResultsPresumptive detection and quantification of Campylobacter spp. and Yersinia spp., and statistical analysis of the resultsCampylobacter spp. presumptive colonies were not detected in any of the processed samples and dilutions. Consequently, we assumed that Campylobacter spp. were either absent in the analyzed samples, or present at concentrations below 10CFU/g food, which corresponds to the lower limit of detection of the methodology used.

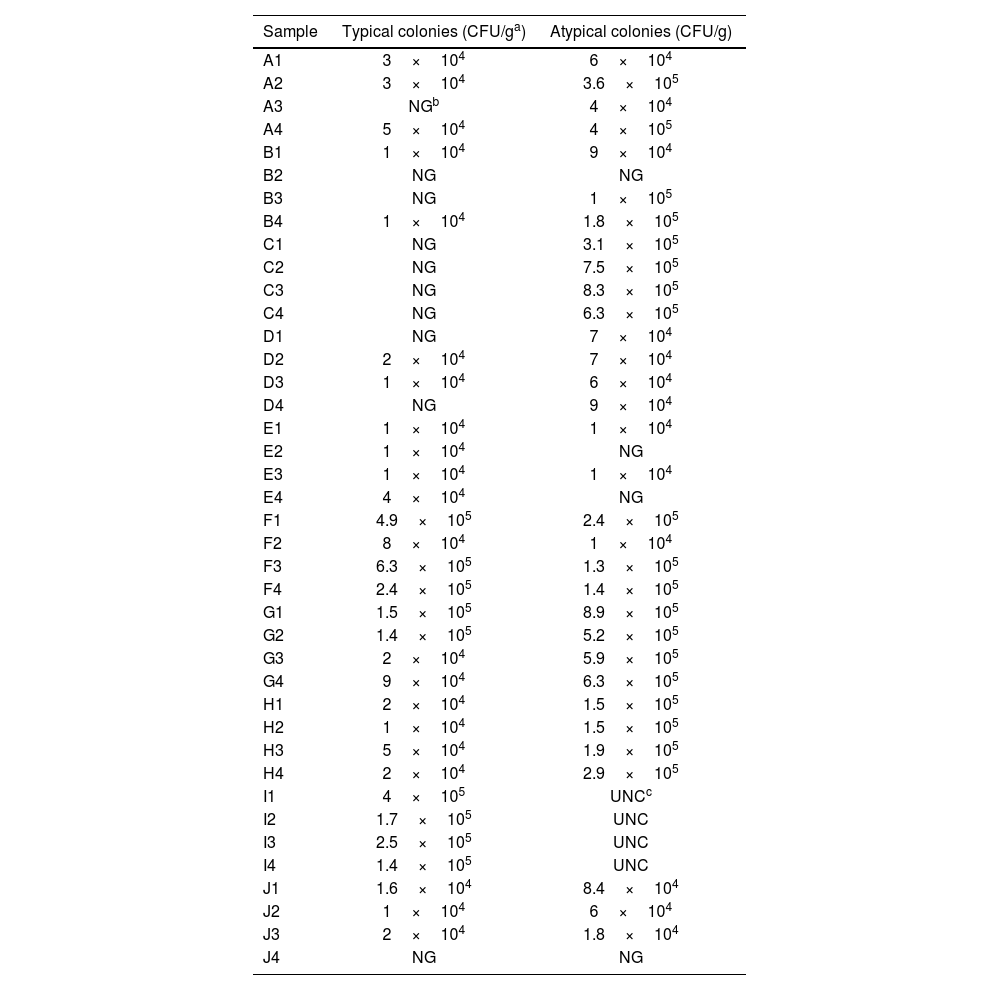

On CIN medium, two types of colonies, differing in size and color, were observed. On the one hand, small colonies with a diameter of 0.5−1mm were detected after 24h of incubation at 30°C, displaying an intense pink color at the center surrounded by a transparent or translucent halo, characteristic of the “red bull's eye” appearance and morphologically compatible with most strains of Y. enterocolitica. On the other hand, larger colonies (with a diameter greater than 2mm), intensely fuchsia in color without a surrounding halo, either colorless or slightly colored, were also observed. They were considered “atypical colonies”, as they usually correspond to taxa other than Yersinia spp., although other strains of the genus may present this phenotype. The differential counts of the colonies grown on CIN are shown in Table 2. The comparison between red bull's eye and atypical CFU/g counts for each sample is presented in Figure 1. There is clearly a higher median and more variation in the atypical CFU/g measurements. The heat map of typical and atypical colonies on CIN (Fig. 2) indicates that the highest concentrations of both colony types are in the lower-central section of the sampling grid, corresponding to samples collected from the commercial stands at the Central Market of Reus. Notably, red bull's eye CFU/g exhibits greater variability, with numerous samples showing no growth, whereas atypical colonies generally display higher counts and a more consistent presence across the sampled locations. Based on the Shapiro–Wilk test results, both variables are not normally distributed (p-value <0.05). Given this non-normality, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used instead of a t-test. Mann–Whitney U test results were: statistic=404.0; p-value=0.000132. The Mann–Whitney U test shows a highly significant difference between the two groups (p<0.001), confirming a non-parametric approach. The Spearman Rank Correlation coefficient was 0.385237, and the p-value: 0.0141. There is a moderate positive correlation (ρ≈0.39) between red bull's eye and atypical CFU/g, which is statistically significant (p<0.05). The Median test result was 12.808005, with a p-value of 0.000345. The Median test confirms significant differences between the groups (p<0.001), indicating that the central tendencies of the two groups are different. Moreover, the Cliff's Delta (effect size) was approximately −0.50, indicating a medium to large effect size, suggesting that atypical CFU/g tends to have higher values than red bull's eye CFU/g. Statistics are shown in Table 3. In brief: the atypical CFU/g has a higher mean (303925) compared to red bull's eye CFU/g (79400); both measurements show considerable variation; and there are samples with 0CFU/g in both categories.

Enumeration of typical (red bull's eye; presumptive Yersinia spp.) and atypical colonies count on CIN medium. The data show significant variation, and several samples presented no detectable CFU/g in either category.

| Sample | Typical colonies (CFU/ga) | Atypical colonies (CFU/g) |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | 3×104 | 6×104 |

| A2 | 3×104 | 3.6×105 |

| A3 | NGb | 4×104 |

| A4 | 5×104 | 4×105 |

| B1 | 1×104 | 9×104 |

| B2 | NG | NG |

| B3 | NG | 1×105 |

| B4 | 1×104 | 1.8×105 |

| C1 | NG | 3.1×105 |

| C2 | NG | 7.5×105 |

| C3 | NG | 8.3×105 |

| C4 | NG | 6.3×105 |

| D1 | NG | 7×104 |

| D2 | 2×104 | 7×104 |

| D3 | 1×104 | 6×104 |

| D4 | NG | 9×104 |

| E1 | 1×104 | 1×104 |

| E2 | 1×104 | NG |

| E3 | 1×104 | 1×104 |

| E4 | 4×104 | NG |

| F1 | 4.9×105 | 2.4×105 |

| F2 | 8×104 | 1×104 |

| F3 | 6.3×105 | 1.3×105 |

| F4 | 2.4×105 | 1.4×105 |

| G1 | 1.5×105 | 8.9×105 |

| G2 | 1.4×105 | 5.2×105 |

| G3 | 2×104 | 5.9×105 |

| G4 | 9×104 | 6.3×105 |

| H1 | 2×104 | 1.5×105 |

| H2 | 1×104 | 1.5×105 |

| H3 | 5×104 | 1.9×105 |

| H4 | 2×104 | 2.9×105 |

| I1 | 4×105 | UNCc |

| I2 | 1.7×105 | UNC |

| I3 | 2.5×105 | UNC |

| I4 | 1.4×105 | UNC |

| J1 | 1.6×104 | 8.4×104 |

| J2 | 1×104 | 6×104 |

| J3 | 2×104 | 1.8×104 |

| J4 | NG | NG |

Heat map showing the distribution of typical and atypical colony counts (CFU/g) on CIN medium by sample. The highest counts for both colony types are concentrated in the lower-central section of the sampling grid, corresponding to samples obtained from commercial stands at the Central Market of Reus. Red bull's eye (typical) colonies exhibit greater variability, with several samples showing no detectable growth, whereas atypical colonies tend to present higher counts and a more consistent presence across the sampling area.

Summary statistics of typical (red bull's eye; compatible with Yersinia spp.) vs. atypical colony counts. The atypical colonies have a higher mean (303925) compared to red bull's eye colonies (79400) count.

Gram negative bacterial strains from A1 to D4, E3 and I4 samples had a biochemical profile compatible with Pseudomonas spp. (family Pseudomonadaceae, class Gammaproteobacteria) (Supplementary table; grey background). Bacterial strains from E1, E2, E4, G2, H1 and J2 samples showed a biochemical profile compatible with Serratia liquefaciens (family Enterobacteriaceae, class Gammaproteobacteria) (Table 2; salmon background); however, the bacterial strain from H4 showed a profile compatible with Yersinia sp. (Supplementary table; blue background). The remaining bacterial strains belonged to the family Enterobacteriaceae (class Gammaproteobacteria) (Supplementary table; white background).

MALDI-TOF identificationUsing MALDI-TOF the bacterial identity at the species level was confirmed when the score value was >2, the spectrum quality was classified as ++/+++, and the consistency index was A or B. Overall, general, our results showed higher scores than 2.0 and Yersinia intermedia was identified only in one case. The rest of the bacterial strains corresponded to species of the genus Pseudomonas and Serratia (Table 4).

MALDI-TOF MS-based identification of bacterial strains with red bull's eye morphology on CIN.

| Strain | MALDI-TOF score value | Identification |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | 2.066 | Pseudomonas libanensis |

| A3 | 2.026 | Pseudomonas tolaasii |

| B2 | 2.097 | Pseudomonas libanensis |

| C2 | 2.117 | Pseudomonas libanensis |

| C3 | 2.246 | Pseudomonas libanensis |

| D2 | 2.147 | Pseudomonas synxantha |

| D4 | 2.183 | Pseudomonas libanensis |

| E1 | 2.438 | Serratia liquefaciens |

| E2 | 2.387 | Serratia liquefaciens |

| G2 | 2.452 | Serratia liquefaciens |

| H1 | 1.801 | Serratia sp. |

| H4 | 2.424 | Yersinia intermedia |

| I4 | 1.982 | Pseudomonas sp. |

| J2 | 2.242 | Serratia liquefaciens |

The WHO published a report estimating 600 million cases of foodborne illness and 420000 deaths in 2010. Children less than 5 years-old is a high susceptible population, with an estimated rate of 120000 deaths per year attributed to unsafe food. This report28 examined the global public health burden of infections based on 31 foodborne hazards. These data highlight the importance of implementing food safety measures to protect vulnerable populations.

FBDs represent one of the most common and important public health issues worldwide. According to WHO, 23 million people in the European Union (EU) fall ill, and 5000 die every year due to FBDs29. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that FBDs affect 48 million people annually, with 128000 hospitalizations and 3000 deaths in USA10. Campylobacter is the most common genus involved in human bacterial gastroenteritis globally, and campylobacteriosis is commonly reported as zoonosis in the EU since 200526.

Microbiological guidelines, such as Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points, Good Manufacturing Practice, and good hygienic practices developed by the WHO and the United States Food and Drug Administration should be implemented strictly to prevent Staphylococcus aureus contamination. Areas where MRSA patients are nursed should be thoroughly cleaned using disinfectants7.

Molecular methods, including mass spectrometry and PCR-based multiplex panels have been developed for the detection of enteric bacteria, and some laboratories are beginning to incorporate the techniques9. These methods have the potential to improve our ability to provide rapid and accurate identification, but it is also important to understand their limitations. Commercial MALDI-TOF MS instruments can provide rapid identifications of Salmonella and Yersinia, but a limited identification of Shigella spp. In our study we used MALDI-TOF for strain identification, which increased the veracity of the results8.

The parametric tests consistently show significant differences between the two groups of bacterial colonies, red bull's eye and atypical, growing on CIN. There is a moderate positive correlation between the two measurements, such as CFU/g. The effect size is substantial, indicating meaningful practical differences. The atypical CFU/g consistently shows higher values than red bull's eye CFU/g. Based on our results, high counts of Pseudomonas spp. and of S. liquefaciens in chicken burger samples acquired in supermarkets, but specially in the stands of the Central Market of Reus. Pseudomonas spp. and of S. liquefaciens colonies growing on cefsulodin–irgasan–novobiocin (CIN) agar resemble those of Yersinia spp. (red bull's eye aspect), which is a great inconvenience for a differential count and to isolate Yersinia spp. to improve their identification. Although Schiemann, the developer of the CIN medium24, reported that it inhibits the growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia marcescens, other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family – such as Citrobacter freundii and S. liquefaciens – are capable of growing on the medium and may produce colonies that resemble those of Yersinia species25. Despite the absence of Campylobacter spp. and Yersinia spp. (except for one strain of Yersinia intermedia) in our samples, the high levels of campilobacteriosis13 and yersiniosis in Spain21 underscore the importance of continuing to study its presence in foods of animal origin.

Food contamination by Pseudomonas spp. mainly occurs through contact with contaminated water, floor particles, and inefficient surface decontamination that come into contact with food6. The genus Pseudomonas is the most frequently implicated in food spoilage because it can produce biofilms6 and extracellular enzymes, such as various proteases and lipases, which are often heat-resistant, leading to spoilage and stability problems in food4,22. Additionally, Pseudomonas spp. are usually isolated from food along with other genera, such as Listeria, Salmonella or Serratia.

ConclusionThe presence and high counts of Pseudomonas spp. and S. liquefaciens in poultry meat burgers could be attributed to inadequate washing of the meat, insufficient disinfection of food processing surfaces, or excessively long refrigeration periods aimed at maximizing poultry shelf life. Consequently, we highlight the need to improve hygienic and sanitary conditions in meat derivative processes, considering the high levels of contamination by psychrotrophic Gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, our study raises questions about the high selectivity of CIN medium for detecting Yersinia spp. in food. In light of these findings, more selective culture media should be developed to detect Yersinia spp. in food samples.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the Universitat Rovira i Virgili and Mycology Unit for providing the laboratory and the consumables essential for carrying out this work.